3. Results

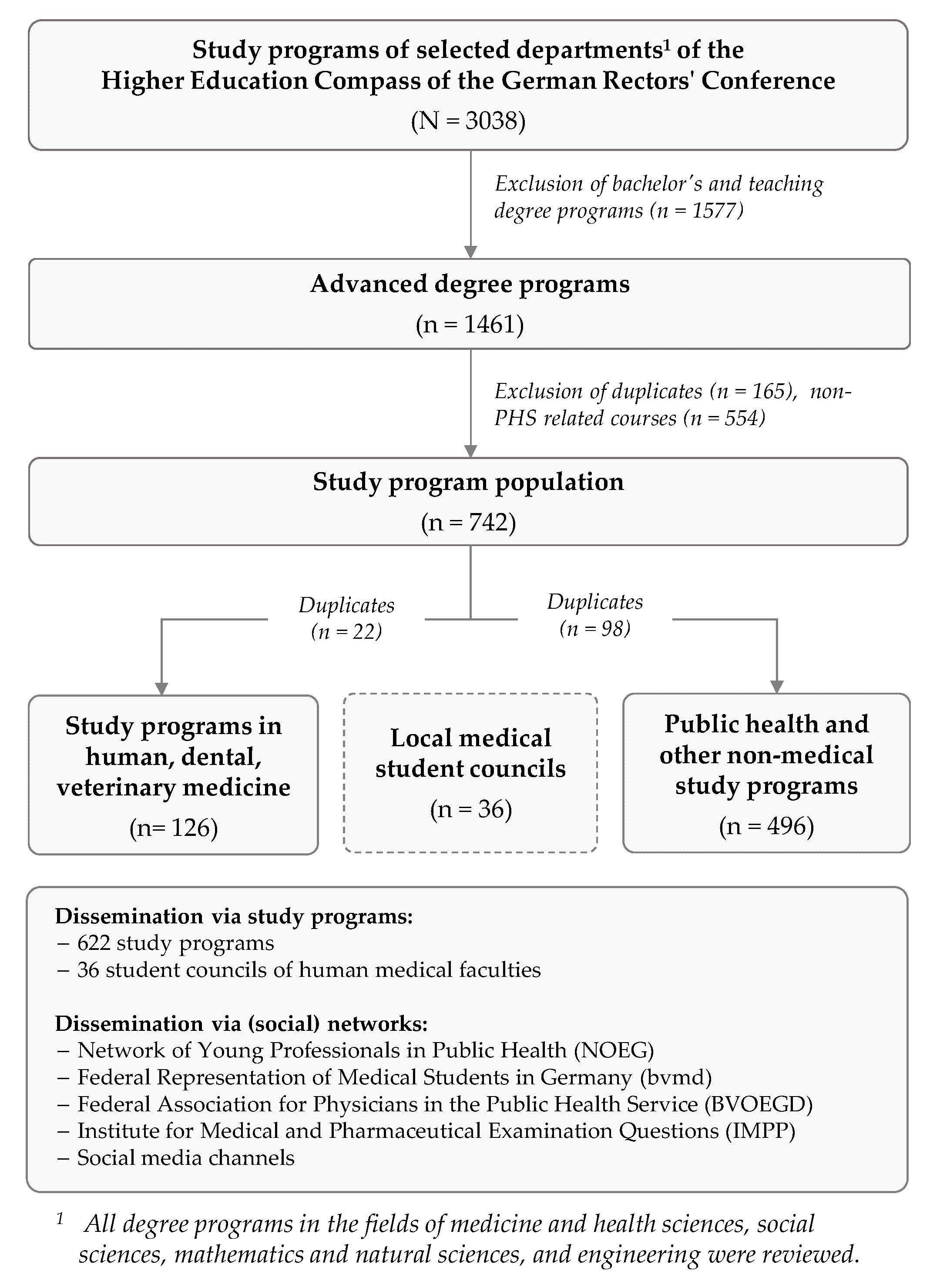

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 2450 students participated in wave 1 and 569 in wave 2. The majority of all 3019 respondents were females (74%), with a mean age of 25.0 years (±5.3 SD). Medical students accounted for 68% of the respondents, students of public health for 15% and students of other studies qualifying for the PHS, such as sociology, social work, biology, engineering or public administration, for 17%. Due to the unequal group sizes, we will distinguish between medical students (MS) and public health and other non-medical (PH&ONM) students in the following. Key characteristics of the included study participants are provided in

Table 1.

As expected, considerably more women than men took part in both waves. The study population was slightly younger in wave 1 (24.6 years, ±4.8 SD) than in wave 2 (26.1 years, ±6.8 SD), with students who reported a general interest in working in the PHS tending to be older than students without such an interest. Fewer medical students participated in wave 2, in particular fewer medical students without interest in working in the PHS. Overall, 17% of all participants stated to have a second degree, i.e., being enrolled in another minor or having completed an additional degree in advance, with students with PHS interests again more prevalent. In wave 2, we also asked whether students had gained initial work experience in the PHS in Germany, such as during an internship or part-time employment. Students with experience were more likely to show general PHS interest than students without prior experience. Due to the cross-sectional study design, however, no further (especially causal) interpretations are permitted in this regard.

3.2. General Interest in Working for the PHS in Germany

Overall, 13% of the participants reported that they can generally imagine themselves working in the PHS. This general PHS interest was much more pronounced among PH&ONM students than among medical students in wave 1 and 2 (

Table 2). Considerably fewer students could imagine working in the PHS at the municipal level than at the federal or national level, with apparent differences between medical students and PH&ONM students.

While 27% of all medical students and 66% of all PH&ONM students could imagine working in the PHS in general (“yes” or “rather yes”) in wave 1, this was an option for 37% of the medical students and even 81% of the PH&ONM students in wave 2. More medical students could imagine working at the federal or national level in wave 2 (50%) than in wave 1 (29%), while the proportion among PH&ONM students was about the same in both waves. In order to distinguish between students with and without general PHS interest in the following analysis, all statements of general interest that participants answered “yes” or “rather yes” were subsumed into the binary index “PHS interest”.

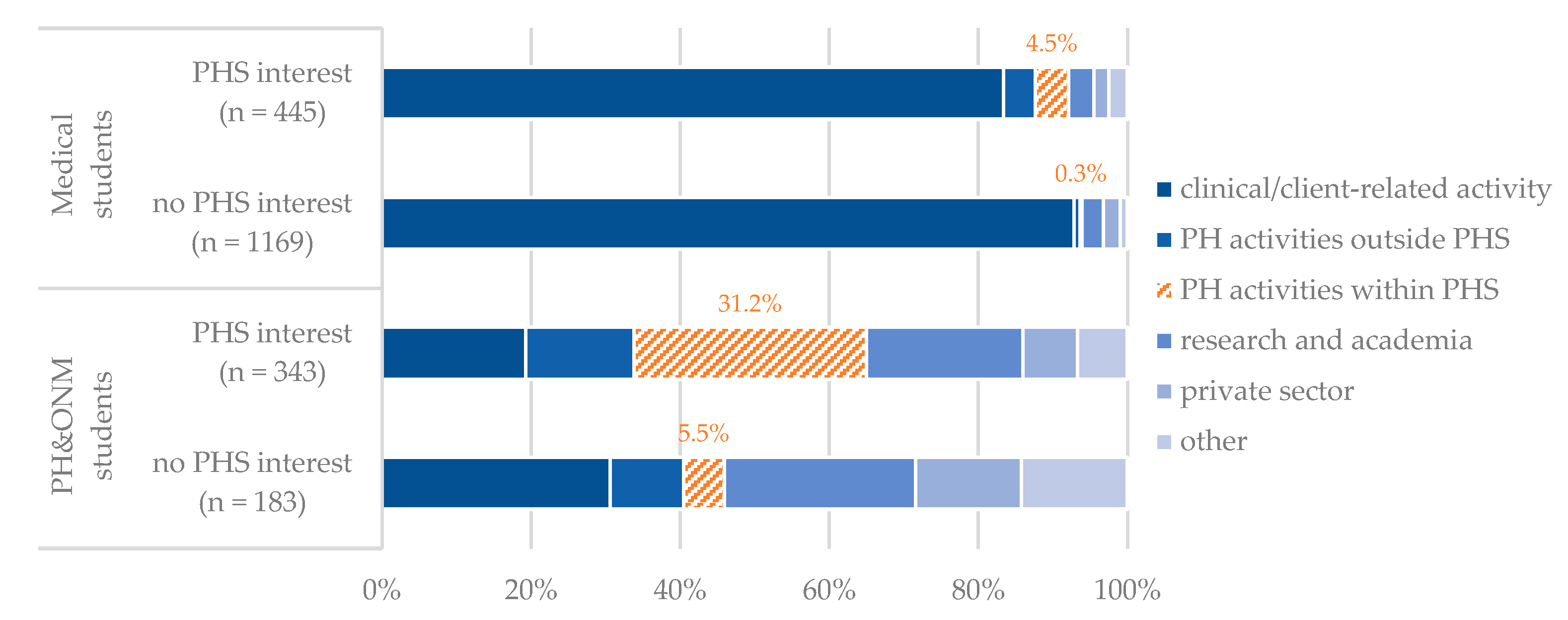

3.3. Interest in Working in a PHS-Related Field

In wave 1, we explored the preferred field of work after graduation by asking all participants to rate various areas of work according to their personal preference. The majority of participants ranked a clinical, client-related activity on top (74%), research and academia were prioritized by 8% and public health activities within the PHS by 7%. Of all medical students with PHS interest, 83% prioritized a clinical, client-related activity compared to 93% of medical students without PHS interest. Among PH&ONM students with PHS interest, 19% prioritize a clinical, client-centered activity compared to 31% with no interest. A public health-related activity within the PHS was prioritized by 31% of PH&ONM students with PHS interest and 5% of the medical students with PHS interest (

Figure 3, more details can be found in

Table A1 in

Appendix A).

The results from wave 1 were validated in wave 2 by surveying the preferred fields of activity after graduation using a four-point Likert scale ranging from “No, definitely not” to “Yes, definitely”. While every second PH&ONM student with PHS interest could imagine a public health-related activity within the PHS in wave 2 (49%), this was an option for only one in four medical students with PHS interest (24%). The proportion of those who could envision a clinical, client-related work was correspondingly lower. More details can be found in

Table A2 in

Appendix A.

3.4. General Knowledge about Population-Based Public Health Approaches

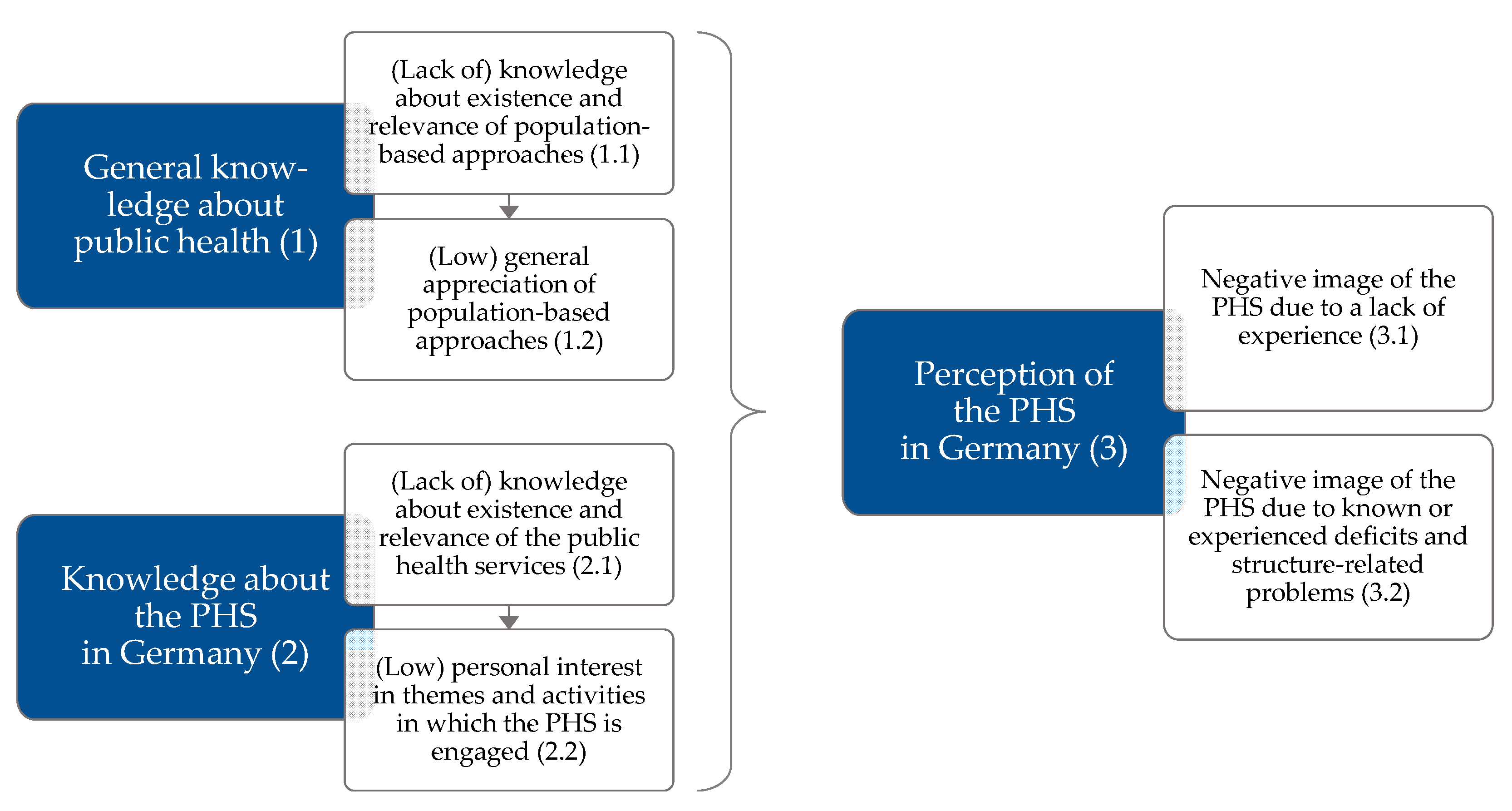

To identify factors that might be related to an interest in working in the PHS in the future, we surveyed differences in knowledge about public health in general and collected data on the perceived impact of various public health interventions, according to part 1 of the logic model (

Figure 1).

As a proxy for existing knowledge about public health in general, participants were asked in several multiple-choice questions to estimate trends in life expectancy (LE) in high- and low-income countries, to estimate differences in LE between groups of high and low socioeconomic status, and to estimate LE differences between men and women. While the average shift in LE in high-income countries over the last 30 years was answered correctly by almost 75% of all participants (with no apparent difference between medical and PH&ONM students, regardless of PHS interest), the situation in low- and middle-income countries seemed to be unknown for the broad majority, as only 10% answered this question correctly (again, with negligible differences between medical and PH&ONM students). While differences in LE among women with low and high socio-economic status (SES) were correctly estimated by one out of three participants (29%), only about one out of ten correctly assessed differences in LE between men with low and high SES. No notable differences between MS and PH&ONM students were found in this regard.

Medical students with PHS interest estimated the average difference in LE between women and men more often correctly (60%) than MS without interest (54%). Other than that, we found no differences between students with and without PHS interest. See

Appendix A Table A3 for more details. Overall, about 37% of all study participants answered only one of five questions correctly, about one-fifth estimated at least three questions correctly (22%), and at least four correct answers were given by a mere three participants. We found no relevant difference in the number of correct responses between medical students and PH&ONM students with and without PHS interest.

In order to assess the perceived importance of public health measures, participants were asked to rank a broad variety of public health measures and interventions according to their estimated relevance for improving LE in Germany over the past 120 years. Medical therapy of infectious diseases in terms of antibiotics was ranked among the top three by more than two thirds of all medical students with PHS interest (70%) as well as all PH&ONM students (66%), followed by primary medical prevention (58% of MS and 48% of PH&ONM students with PHS interest), and measures to reduce poverty or malnutrition (55% of MS and 47% of all PH&ONM students with PHS interest). Non-medical preventive measures and health promotion measures, such as smoking bans or measures to increase health literacy, were prioritized by 16% of all participants with almost identical proportions between MS (17%) and PH&ONM students with PHS interest (18%). Minor importance was also attributed to secondary prevention measures, such as cancer screening, by 15% of all interested MS and 20% of all interested PH&ONM students.

More PH&ONM students without PHS interest rated primary medical prevention measures as relevant (64%) than PH&ONM students with PHS interest (48%). Besides that, we found no relevant differences regarding the assumed public health impact between medical students and PH&ONM students with and without PHS interest. See

Appendix A Table A4 for more details.

3.5. Knowledge about and Interest in Specific Topics, Tasks and Activities of the PHS in Germany

To analyze the lack of knowledge about PHS-relevant tasks and activities as postulated in part 2 of the logic model (

Figure 1), associations with and attributions to six core public health fields of activities were surveyed in wave 1. Based on three questions, all participants were asked if they associate the given fields of activity with the PHS, to what extent the fields of activity were part of their studies, and whether the activities are suitable for themselves in the future. The main results are briefly summarized below, more detailed information can be found in

Table 3.

Primary and secondary prevention and supporting vulnerable groups were not associated with the PHS by 33% of participants each. Minor differences were notable between medical students without PHS interest, who were less likely to attribute supporting measures, prevention measures, and health protection measures to the portfolio of the PHS than MS with PHS interest.

The curricular anchoring of the six public health core areas varied greatly: While (medical) primary and secondary prevention was reported to be intensively covered within medical (61%) as well as PH&ONM study programs (52%), outbreak and crisis management was hardly present in both. Health planning and policy advice were stated as intensely covered by 31% of all PH&ONM students compared to 2% of all medical students. Working with vulnerable groups, and behavioral and primary prevention interventions were also more often reported as intensively covered by PH&ONM students. Health protection and infection disease prevention and (medical) primary and secondary prevention, on the other hand, were more frequently indicated as addressed intensively within the medical curriculum (

Table 3).

Students with PHS interest were more likely to state that one of the six core public health fields would be an option for them compared to students with no interest. Primary and secondary prevention were by far the most commonly considered by medical students interested in the PHS (81%), followed by working with vulnerable groups (70%). Among PH&ONM students behavioral and primordial prevention, support of vulnerable groups and health planning and policy advice were considered most frequently.

3.6. Interest in Core Public Health Fields of Activities Regarding Their Curricular Coverage and Attribution to the PHS in Germany

Interest in the six core areas was also compared with the extent to which the participants reported that the topics were intensively covered during their main studies and attributed to the PHS in Germany.

Relevant differences emerged in particular in the areas of health planning and policy advice, outbreak and crisis management, and supporting vulnerable groups: In all three areas of activity, medical students, for whom the occupational fields were an attractive option after graduation, reported at the same time a low level of anchoring in their studies (

Table 4). A large proportion of PH&ONM students with an interest in working in outbreak and crisis management reported marginal anchoring in their studies.

About one third of students interested in primary or secondary prevention or in supporting vulnerable groups do not attribute these activities with the PHS. In the areas of outbreak and crisis management, health planning/policy advice, and behavioral and primary prevention, the proportion was about 25% each, with no noticeable differences between medical students or PH&ONM students (

Table 4).

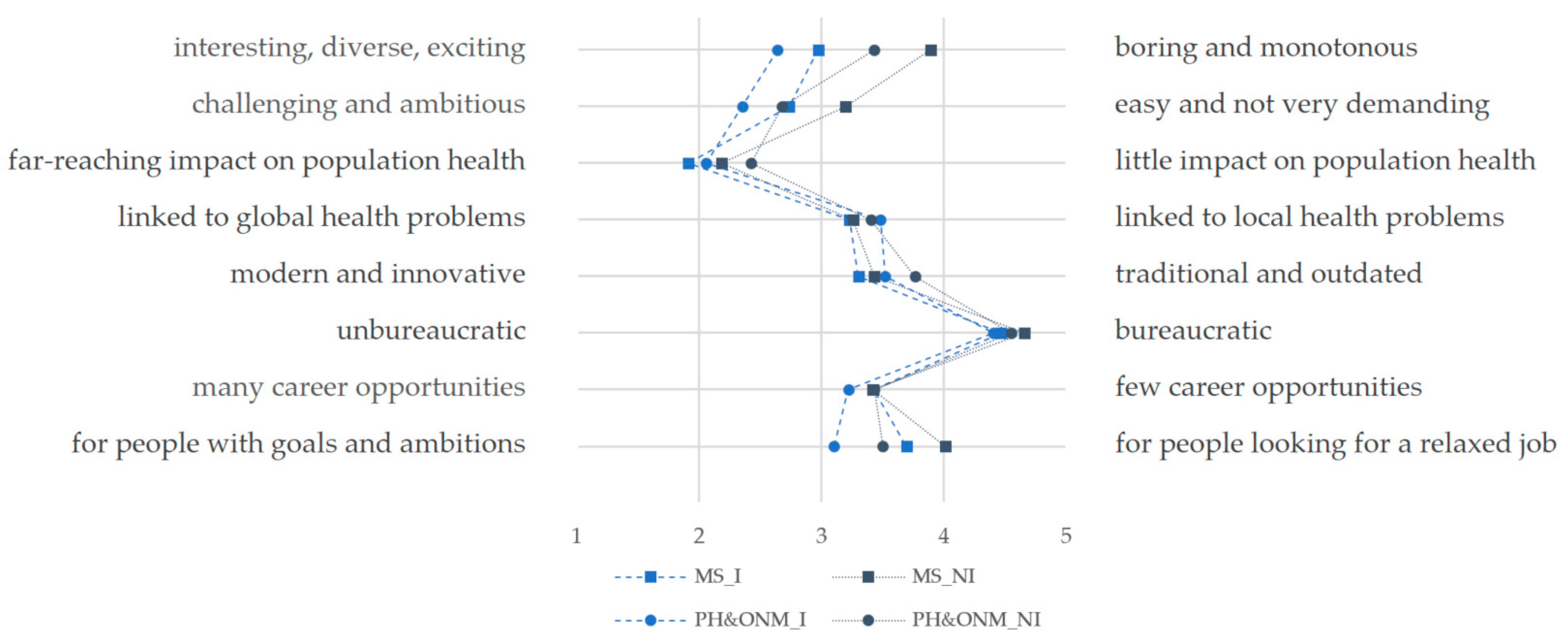

3.7. Perception of the PHS

To assess part 3 of the logic model (

Figure 1), characteristics associated with the PHS were collected using multilevel polarity profiling in waves 1 and 2. All of the in total eight contrasting juxtapositions could be assigned to five levels, so that all participants could choose which expression (e.g., ranging from interesting, diverse, and exciting to boring and monotonous) they most closely associated with the PHS.

Both medical students and PH&ONM students with PHS interest were more likely to characterize the PHS as interesting, diverse and exciting, to consider PHS-related tasks and activities as challenging and demanding, and to attribute a high overall impact on population health to the tasks and activities of the PHS compared to students without PHS interest (

Figure 4).

Almost regardless of the general PHS interest, the vast majority of all students characterized the PHS as highly bureaucratic (93% of all medical students and 89% of all PH&ONM students). Furthermore, the PHS was more likely to be associated with individuals who were interested in a relaxed job than with people with goals and ambitions. The latter is much more pronounced among medical students with PHS interest (63%) than among interested PH&ONM students (33%). PH&ONM students were slightly more positive in their characterization of the PHS than medical students, as well as students with general PHS interest. More detailed information can be found in

Figure A1 and

Table A5 in

Appendix A.

To account for potential differences according to any prior experience, the results from wave 2 were stratified accordingly: Students with previous experience working in the PHS in Germany were more likely to describe the PHS as interesting, challenging, and exciting (37%) than students without (26%). Otherwise, we found no relevant differences according to prior PHS experience. More detailed information can be found in

Table A6 in

Appendix A.

3.8. Expectations for Working Life and Career

In order to identify factors that could improve the attractiveness of the PHS as a prospective employer in general, we surveyed criteria that students consider to be particularly important for their future working life in wave 1. A total of 20 different aspects were queried using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “unimportant” to “very important”.

Compatibility of career and family (70%) and good work-life balance (67%) were by far the most important rated aspects for both, medical students and PH&ONM students with PHS interest (

Table 5). While medical students with PHS interest ranked direct contact with patients or clients (44%), followed by the opportunity to help people directly (42%) and job security (39%) among the top five aspects of a good work life, PH&ONM students with PHS interest prioritized job security (38%), regular working hours (38%) and good social benefits (34%). Contrary to our expectations, a mere of 13% of all participants with PHS interest considered a high salary to be of particular relevance (12% of all medical students with PHS interest and 15% of all PH&ONM students).

We validated the results from wave 1 by asking all students in wave 2 to rank in total eleven thematically clustered aspects based on their importance regarding their future working life. Again, work-life balance and an appreciative and good working atmosphere were rated highest by all participants. Relevant differences were also found regarding the importance of job security, which was ranked more often as important by students with PHS interest (24%) than by students without (16%). Furthermore, job security was considered as very important more often by PH&ONM students than by medical students. As in wave 1, students without PHS interest considered individual patient care/client-related work more often as important (32%) than students without PHS interest (16%), with the high interest primarily attributable to medical students without PHS interest (41%). More details can be found in

Table A7 in the

Appendix A.

3.9. Expectations for Training and Education

Finally, wishes and expectations for (future) education and training of public health-relevant content were captured in both waves 1 and 2, using various multiple-choice questions. In wave 1, almost twice as many medical students with PHS interest (62%) could imagine learning about public health topics as part of a compulsory elective (in German: Wahlpflichtfach), compared to medical students without interest (34%). Medical students with an interest in the PHS were more likely to envision themselves completing a one-month internship in medical school (in German: Famulatur) or a term of their practical year (in German: Praktisches Jahr) within the PHS than medical students without an interest in the PHS (

Appendix A:

Table A8).

The public health specialist training, a residency training program qualifying physicians explicitly for the work in the PHS in Germany, was known by 40% of all medical students, with relevant differences between medical students with PHS interest (46%) and those without (38%). When asked what medical specialist training would be of general consideration, a specialty in public health (in German: Facharzt für Oeffentliches Gesundheitswesen) was by far the least frequently mentioned specialty with 6% of all responses in wave 1. In the second survey in wave 2, about 16% of medical students indicated a general interest in the public health specialty (

Appendix A:

Table A9). Furthermore, PH&ONM students were asked in wave 2 whether they would consider a public health specialist training if such a program was associated with appropriate job and career opportunities and were open to qualified individuals without a medical degree. The vast majority of all PH&ONM students could envision themselves doing such a training (70%).

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge this is the first empirical study that investigated the attractiveness of the PHS as a potential employer among medical and PH&ONM students in Germany.

| Key finding 1. High levels of interest in working in the PHS exist in PH&ONM students—reflecting on relevant activities within the PHS could help to make use of an underutilized pool of qualified employees. |

In line with previous studies [

36,

57], we found low levels of interest in the PHS among medical students. Almost three out of four medical students expressed a tendentious or categorical lack of interest and only 6% said they could imagine working in the PHS. Our study adds that among those medical students with PHS interest, almost nine out of ten stated that their main interest lay in clinical/client-related activity. In contrast to the medical students, the interest in working in the PHS among PH&ONM students was relatively high, with almost three out of four students expressing a tendentious or definite PHS interest.

In order to ensure the functioning of the PHS with its complex tasks, roles and responsibilities, and to be able to respond instantaneously and efficiently in times of crises, an efficient PHS workforce requires well-qualified professionals possessing comprehensive skills and competencies [

58] from a broad variety of disciplines and professions. However, the debate about the shortage of personnel in the PHS in Germany so far has largely focused on medical students and physicians [

59], whose basic training does not encompass all the competencies needed for the work in the PHS [

60]. While medical professionals are and will remain essential for an effective PHS [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63], our finding on the disproportionately higher level of interest in the PHS among PH&ONM students indicates that part of the current PHS workforce shortage in Germany could be overcome if the role of public health professionals without medical degrees is strengthened. One solution could be to apply the taxonomy proposed by WHO and the Association of Schools of Public Health in the European Region (APSHER) in their Roadmap for Professionalizing the Public Health Workforce: Instead of primarily focusing on individual professions, they suggest to differentiate by (core) areas of activity and corresponding competencies [

61], which in turn could be assigned to professionals with suitable expertise in the particular topic or task. However, establishing such an approach in Germany would first require mapping the numerous activity profiles within the PHS, to provide the basis for an evidence-informed restructuring. While surely a challenging endeavor, focusing on expertise rather than individual professions could help to reach the full potential of a multi- and interdisciplinary public health workforce while balancing workforce supply and employer demand [

60,

61].

| Key finding 2. Students tend to underestimate the impact of public health approaches—overcoming this may increase awareness of the PHS |

Within our logic model, we postulated that a lack of interest in (

Figure 1: 1.1) and appreciation of (

Figure 1: 1.2) the importance of population-based public health approaches could contribute to low attractiveness of the PHS among students. We found that only one in five participants was able to correctly answer at least three out of the five multiple-choice questions on trends and differences in LE. When asked about the main reasons for the increase in LE over the past 120 years, we found most participants overestimating the importance of medical practices and innovations, while underestimating the importance of changes in living conditions and public health interventions. While we did not find relevant differences in these knowledge domains between individuals with and without PHS interest, we found that considerably more students without interest associated the PHS with a lack of impact.

We are aware that—despite the importance of LE as an indicator to monitor population health [

64,

65]—knowledge of differences and changes in LE can only serve as a rough proxy for the level of public health knowledge. However, our findings are in line with other studies showing that the contribution of medical care to increased LE in the general population is often overestimated to the detriment of public health measures and improved social conditions, which in turn tends to be underestimated [

66].

Underestimating the importance of public health measures for improving health and wellbeing [

67] while overestimating the importance of medical interventions may lead individuals who are strongly motivated to make a difference not to pursue a career in public health. There are many factors that could explain why students struggle to assess trends and differences in LE correctly. In addition to gaps in general education and misreporting in the media, the correct assessment is also likely to be hampered by the lack of curricular anchoring within medical studies [

68,

69]. While our findings indicate a more complex relationship between public health knowledge and interest in working in the PHS, the identified gaps in knowledge support previous calls for including or strengthening public and global health components in the curriculum of all PHS-relevant professions [

70]. Integrating PHS-relevant topics into the curricula and highlighting the importance of population-based approaches could raise awareness about the PHS as an attractive employer.

| Key finding 3.Students lack awareness about topics, tasks and activities of the PHS in Germany—more presence in the study programs, tailored training approaches and increased visibility of the PHS could change this |

A second dimension of our logic model assumed that low levels of knowledge about the existence and activities of the PHS (

Figure 1: 2.1) may contribute to a lack of interest in working in the PHS among students and young professionals. This is reflected in our findings, as—in addition to the underestimated impact of population-based approaches—the majority of students was not very familiar with the broad spectrum of PHS tasks and activities. We found that many participants did not associate the PHS with parts of its core topics and functions: While only one in six participants did not consider health protection and infection disease prevention to be a core function of the PHS in wave 1, this was the case by one in four participants for health planning and policy advice, behavioral and primordial prevention, and outbreak and crisis management. Primary and secondary prevention as well as support of vulnerable groups was not associated with the PHS by one in three participants each. Not ascribing one of these functions to the PHS was associated with an overall lack of interest in the PHS as a prospective employer among medical students but not among PH&ONM students.

Furthermore, we found that participants stated that many PHS core tasks and activities were not intensively addressed during their studies; with considerable differences between medical students and PH&ONM students, ranging from 61% of the medical students stating (medical) primary prevention and secondary prevention were intensively studied, while only 2% made this statement about health planning and policy advice and 3% about outbreak and crisis management.

Thus, our findings are in line with experts and stakeholders from the public health community calling for a stronger anchoring of the PHS and PHS-related topics in the curricula [

68]. Insufficient coverage of public health-relevant topics may contribute to a lack of awareness of the importance of organized efforts needed to improve population health [

71]. The PHS here has an essential role to play, above all the LHA which are predestined for adaptation of (complex) public health measures and concepts to local needs due to their municipal anchoring [

72]. However, this requires qualified public health professionals who have been trained to deal with the vast amount of wicked problems in public health [

61]. To complicate matters, these problems rarely fall within the purview of a single institution or organization [

73] and require inter- or even transdisciplinary collaborations among a broad range of professions [

74].

In order to equip students and (future) public health professionals with appropriate skills and competencies, existing education and training structures need to be reconsidered. Skills for adopting system-wide approaches are just as relevant as critical public health competencies [

75], competencies regarding law and policy formulation and evidence-informed health planning as well as a fundamental understanding of administrative processes and management skills [

76,

77]; all of them require a direct link between theory and practice [

77,

78].

In this context, the possibilities of practice-oriented post-graduate training structures should be explored. With the public health specialist training for physicians [

79], accompanied by the Academies of Public Health, or the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) of the European Center for Disease Control and the Robert Koch Institute as training site in Germany [

80], there are at least two examples of well-established programs in Germany. However, both are either subject-specific (FETP) or profession-specific. Within the scope of the OeGD-Studisurvey we found the broad majority of non-medical students to be interested in a public health specialist training if such programs were associated with appropriate job and career opportunities and open to qualified individuals without a medical degree. This interest could be an opportunity to include students of non-medical study programs in programs preparing for the work in the PHS, especially the work in the LHA. A good example of this is the interdisciplinary training approach of public health consultants and specialists offered by the National Health Service (NHS), which is equally open to medical professionals as well as public health students and students from other PHS-relevant study programs [

81].

The measures initiated a few years ago to increase the attractiveness of general practice as a medical specialty in Germany could provide another useful guidance: In addition to strengthening general medicine by implementing the opportunity to perform a corresponding term of the practical year, the specialty also became an integral part of medical training through the establishment of chairs for general practice and family medicine throughout Germany [

82]. Analogously to the current developments in the PHS, an amendment to the medical licensing regulations was also initial for general medicine, aiming for a stronger thematic anchoring in the medical curricula. Back in 2016, the establishment of PHS chairs, until then already repeatedly demanded by the public health community [

37,

39,

83], was given political endorsement with a resolution of the Conference of Ministers of Health [

3] to strengthen PHS-relevant research and to implement PHS-relevant topics in medical education and training. However, until today PHS chairs are still far from being implemented across the nation. There are so-called “linked professorships” (in German: Brückenprofessuren) at the federal level, which are well suited for the transfer of scientific findings into (local) practice and vice versa due to their double appointment in science and practice [

70,

84]. Without a comprehensive implementation of regular professorships and chairs of PHS, however, it will be difficult to integrate PHS-relevant topics into the (medical) curriculum on a regular basis. The PHS professorships at the universities of Cologne and Frankfurt am Main, which have been advertised in the summer of 2022, are an important first step in this regard.

| Key finding 4.Medical and PH&ONM students are interested in core topics and functions of the PHS in Germany—expanding on and emphasizing them could increase attractiveness |

Another assumed barrier according to our logic model was that students might just not be interested in core topics and functions of the PHS and the resulting tasks and activities that working in the PHS would involve (

Figure 1: 2.2).

This is reflected in our data, as we found that individuals who stated they were interested in working on or in one of these core topics and functions were more likely to consider the PHS as a potential career path. However, we found that both medical students and PH&ONM students were generally interested in selected topics and areas: Even among those individuals who indicated that they were not interest in working in the PHS, between one in four and two in three participants stated, that they could envision working in at least one of the listed core activities.

These findings indicate that a general interest in the core topics and functions of the PHS exists, although this does not necessarily translate into a general PHS interest. However, our findings could be supportive in increasing the attractiveness of the PHS: for example, strengthening topics and functions considered as attractive by many students (e.g., prevention and health promotion) could lead to the PHS be perceived as more attractive. Similar suggestions have been made by other experts and stakeholders in the past [

20,

59]. Furthermore, emphasizing these themes and functions in public awareness campaigns could also serve as a valuable strategy.

| Key finding 5:The PHS in Germany has an image problem, which needs to be addressed—Existing positive associations could form the core of a new public image |

The final dimension of our logic model addressed how the PHS is perceived among students by focusing on barriers hindering individuals in striving for a career in the PHS in Germany. Here, we distinguished between a negative perception of the PHS due to unjustified stereotypes, which e.g., could be overcome by factual knowledge and experience (

Figure 1: 3.1), and a lack of attractiveness of known and experienced characteristics of the PHS, which could not be overcome through knowledge and experience as they require fundamental changes within the PHS (

Figure 1: 3.2).

As our study primarily addressed students with limited insights into the PHS as well as due to our cross-sectional methodology, we are not able to clearly distinguish between the two theses. Nonetheless, our results provide important qualitative and quantitative findings that provide initial empirical insights. While the findings on image and perception of the PHS as a potential employer, derived from an in-depth qualitative analysis, are discussed in more detail in the accompanying paper of the OeGD-Studisurvey [

48], the findings of the quantitative analysis presented in this paper emphasizes the importance of the public image and perception of the PHS.

We found considerably more participants who could imagine working in the PHS having positive associations and attitudes towards the PHS, as did those who were not interested in working there. This includes the PHS being associated with offering interesting, diverse, and exciting work, the tasks within it being challenging or ambitious, resulting in a high impact, or being modern and innovative (or at least not traditional and outdated).

These positive aspects could be utilized by emphasizing them in public awareness campaigns and by engaging in reforms to further strengthen this part of the PHS employer profile. Furthermore, they could be combined with other messages reflective of values important to students who stated that they could imagine working for the PHS, such as that it would provide an appreciative and good working atmosphere, offer a good work-life balance, and that the work profile consists of a diverse set of activities and allows for creative freedoms. Shaping a new public image of the PHS in this way may help to attract young professionals who currently strive for other career paths.

However, it needs to be acknowledged that the PHS has an image problem: Even among those participants who expressed an interest in working in the PHS, one in three medical students considered working in the PHS as boring and monotonous, one in four medical students as not challenging and not ambitious, every second PH&ONM student considered the PHS as outdated and traditional, and nine out of ten participants with interest in the PHS considered the PHS as bureaucratic. While it is beyond the scope of this publication to distinguish between unjustified stereotypes and experienced negative characteristics of the PHS due to existing underlying problems and deficits, it should be noted that changing the public image alone will not lead to a sustainable increase in the attractiveness of the PHS. To do so, the underlying factual problems and deficits must be addressed in the context of an appropriate structural reform [

85,

86].

In doing so, experiences from additional good examples and approaches should serve as a basis: The results of the OeGD-Studysurvey could serve as a starting point for the development of a continuous monitoring of the public health workforce along the lines of the PHWINS study [

87], just as they should be taken into account in the development of new qualification models, as is currently being done in Germany, for example, in the EvidenzOEGD study [

88] or at the European level in the SEEEPHI study [

89]. This requires a joint discourse between science, politics and the professional public, which the present results are intended to encourage.

5. Strength and Limitations

The OeGD-Studisurvey has several strengths and limitations. Although the data collection is based on a comprehensive recruitment strategy, it is not a randomly selected sample. However, we found that, particularly in wave 1, the population of medical students is comparable to the population of a large survey of more than 13,000 medical students in Germany conducted in 2018 [

57]. Similarities can be seen, for example, with regard to interest in working in the PHS or interest in a medical specialist qualification. Unfortunately, for the PH&ONM students, no such reference exists, and it cannot be ruled out that individuals with interest in the PHS are overrepresented due to self-selection.

The proportion of students with a general interest in PHS is higher in wave 2 than in wave 1. There are potentially different explanations for this which must be considered when interpreting the data: We assume that the supposed increase in the attractiveness of the PHS among students overall is mainly due to the slight shift in the population toward more PHS-interested students and fewer medical students without general PHS interest in wave 2. However, due to the cross-sectional design, no causal conclusions can be drawn here. The study design aimed to describe interest in working in the PHS at two different time points. Since the first survey wave was not designed as a follow-up, the two samples do not include the same participants. Thus, the OeGD-Studisurvey can provide important indications, but it is not capable of explaining underlying causes.

It also has to be considered that the population surveyed are students, whose perception and attitudes might change in the early phase of their professional career. Here, conducting additional research among professionals in early stages of their career within and outside of the PHS might provide valuable insights.

The OeGD-Studisurvey was conducted before and in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, the PHS in Germany has received high levels of media, political, and public attention. This has likely raised awareness about the PHS among students and young professionals and may have sharpened their perception of it, both in a favorable or less favorable way. Additional research—for example in the form of a third wave of the OeGD-Studisurvey or even in the context of a continuous monitoring analogous to the PH WINS study in the United States [

87]—might be a possible solution to better assess the development of perceptions of the PHS among students and young professionals in the future.

Despite these limitations, this survey is—as far as we know—the most comprehensive empirical study to date on the perceived attractiveness of the PHS in Germany among students. The general lack of empirical evidence on this topic further highlights the importance of this study.

6. Conclusions

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the PHS has received a great deal of political attention. Existing deficits were discussed publicly for the first time and initial steps to modernize existing structures have already been taken: for example, with the Pact for the Public Health Service in Germany (in German: OeGD-Pakt) [

90] numerous new permanent job positions were created. Medical students meanwhile have the opportunity to conduct part of their electives in the PHS, and the upcoming PHS professorships can help anchoring PHS-relevant topics in the (medical) studies. All of these developments represent a unique opportunity for engaging in a process to reform the PHS towards increasing its attractiveness to sustainably improve recruitment and retention of qualified employees for the PHS in the future.

We believe that such a reform process should be guided by an evidence-informed, deliberative process with all stakeholder involved. The results of and suggestions derived from the qualitative and quantitative analysis of the OeGD-Studisurvey may provide a valuable starting point for such deliberation, as it provides the first empirical data on the perception of the PHS in Germany as a potential employer and the reasons underlying differences in interest among medical and PH & ONM students:

First, in line with established knowledge, our findings showed that while the vast majority clearly had no interest in working in the PHS, a smaller group of students explicitly indicated their interest. A focus on those students and young professionals who are already inclined towards working in the PHS is likely a successful and efficient recruitment strategy. In particular, the high levels of interest among PH&ONM students offers an opportunity to counteract the serious staff shortage. One approach to do so could be to focus recruitment of staff on expertise regarding specific themes, tasks, or skills rather than focusing on degrees or professional backgrounds. This could also help to realize the full potential of a multi- and interdisciplinary PHS workforce, which is urgently needed to address the complex challenges we are currently facing.

Secondly, we found that even students interested in the PHS showed a substantial lack of knowledge about public health and that most students underestimated the importance of public health interventions to improve population health. These misconceptions could lead students interested in achieving impact through their work to seek a career outside of the PHS. The described lack of awareness about the specific topics, tasks and activities of the PHS in Germany among students, could also pose a barrier for entry into the PHS. As also suggested by the German National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina [

91], teaching on public health in general and the PHS in particular should be strengthened—not only in the medical studies in Germany, but also in other study programs of particular relevance for improving public health, such as political sciences, economics, or the social sciences.

Thirdly, the PHS is—at least in theory—the central actor when it comes to improving the health of the population and reducing health inequalities. We found that medical and PH&ONM students were interested in the various core topics and functions of the PHS in Germany and especially on the topic and function of prevention, however, many do not know that those activities are even part of the job profile. This indicates that the PHS has so far not yet been sufficiently successful in focusing on precisely these original activities and promoting them accordingly. One approach to address this could be to focus on those core topics and themes of the PHS, which are of particular interest to students, and emphasize those in public awareness campaigns or other situations in which students are exposed to the PHS. A second approach, which may require more structural reform, could be to strengthen the importance of tasks, topics, and themes of particular interest to students—such as prevention and health promotion—within the occupational profile of the PHS.

Furthermore, our findings show that a number of positive associations with the PHS exist, such as that it provides a workplace that is endowed with numerous aspects considered positive and important by students. Emphasizing such associations in public awareness campaigns and utilizing them to strengthen the PHS employer profile can be a valuable resource. However, given that even participants with a strong PHS interest perceive the PHS as bureaucratic, outdated, and the work as boring, monotonous and not challenging, it must be acknowledged that the PHS has an image problem that needs to be addressed and which likely cannot be overcome without fundamental reform processes within. In line with the findings, potential goals maybe to streamline overly bureaucratic processes, to expand automation and digitalization in administrative tasks, to lower rigid hierarchies, or to provide more creative freedoms.