Reducing Sugar Intake in South Africa: Learnings from a Multilevel Policy Analysis on Diet and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention

Abstract

:1. Introduction

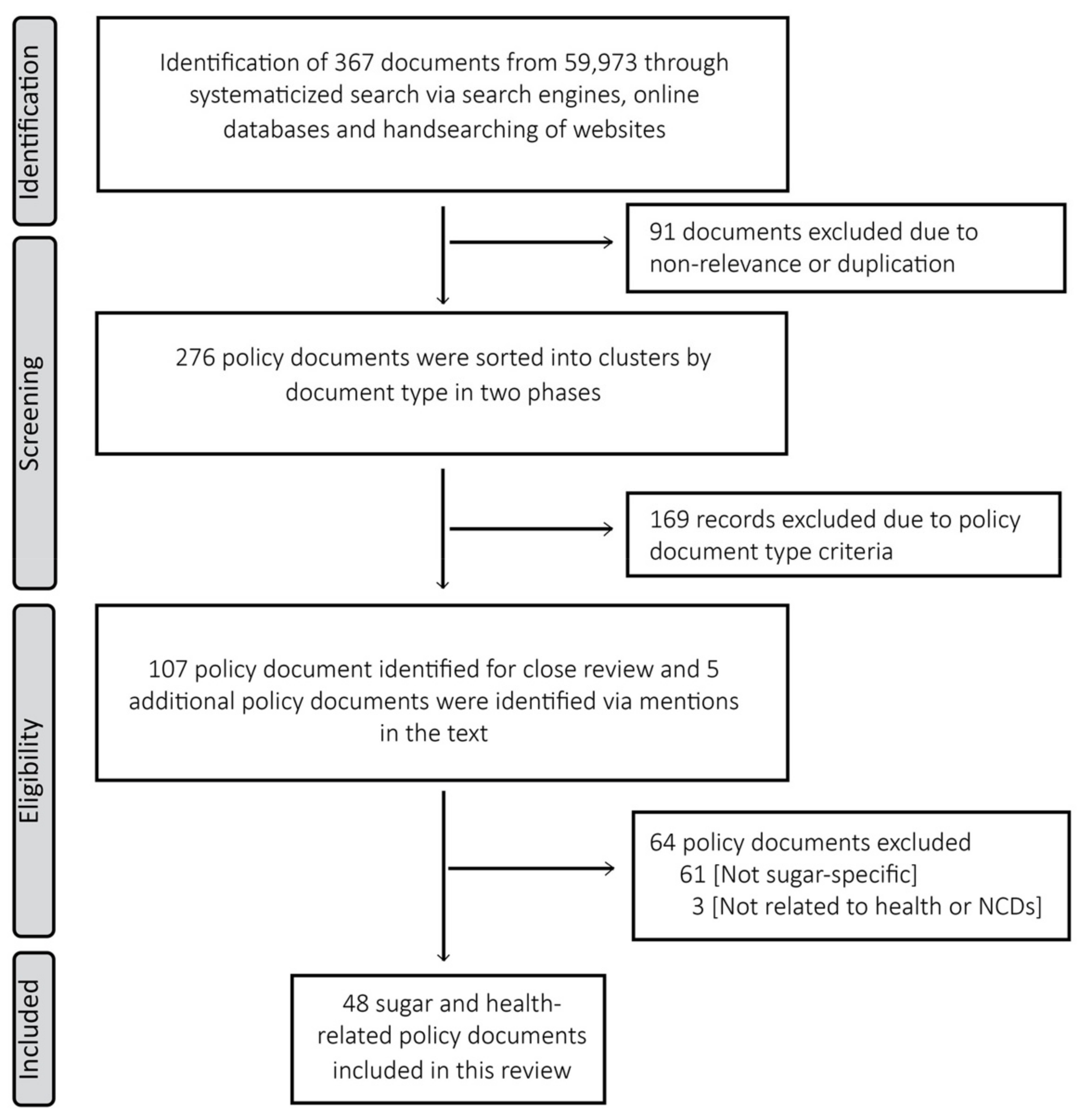

2. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Who Is Involved in the Policy Transfer Process and Why Engage in Transfer?

4.1.1. International Organizations: The WHO/FAO and Codex

The FAO

The WHO

The Codex

4.1.2. National Government

4.1.3. The Private Sector

4.2. From Where Are Policy Directives Drawn?

4.2.1. Global Level Key Policy Ideas

Recognition at a Global Level That Unhealthy Diets and High Sugar Intake Are Related to NCD Burden

“Limiting high intakes of free sugars, which provide energy without specific nutrients and increase the risk of unhealthy weight gain, improves the nutritional quality of diets and decreases the risk of dental decay”.[31]

Recognition of the Added Vulnerabilities of Women and Children, Especially in An Urban Context

“…children should maintain a healthy weight and consume foods that are low in saturated fat, trans-fatty acids, free sugars, or salt in order to reduce future risk of noncommunicable diseases”.

“…children with the highest intakes of sugar-sweetened beverages had a greater likelihood of being overweight or obese than children with the lowest intakes”.

A Multi-Sectoral Approach and Mix of Policy Options Is Needed to Address the Underlying Structural Determinants of NCDs

A Set of Cost-Effective Interventions or “Best-Buys” Are Available for LMICs

“Best buys to reduce major risk factors for noncommunicable diseases include:Reducing salt and sugar content in packaged and prepared foods and drinks”.[50]

4.2.2. Expression of Global Ideas in South African Policies

South African Recommendation and Definition of “Added Sugars”

Sugary Drinks Contribute to Excess Weight and Obesity in Sub-Populations

National Policy Documents Endorse a Multi-Sectoral Approach and Apply Cost-Effective Approach

A Mix of Policy Options Applied in the South African Context

Gaps Identified in Policies Targeting Sugar Intake

“a foodstuff not regarded essential as part of a healthy diet and healthy lifestyle, as listed in Annexure 6 …shall not advertise or promote in any manner, in any school tuck shop or on any school or pre-school premises”.[60]

4.3. Degree of Policy Transfer

4.3.1. Copying

4.3.2. Emulation

5. Discussion

- Policy learning 1: Identify local health priorities and use the WHO ‘roadmap’ for multisectoral and cost-effective policy action

- Policy learning 2: Strengthen participation in global and regional decision-making structures

- Policy learning 3: Build leadership, national capacity and increase provision for technical assistance to overcome policy constraints

- Policy learning 4: Evidenced-based approaches can support advocacy efforts to help combat private sector interference

6. Relevance for Other LMICs and Further Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malik, V.S.; Pan, A.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain in Children and Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 98, 1084–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Te Morenga, L.; Mallard, S.; Mann, J. Dietary Sugars and Body Weight: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Randomised Controlled Trials and Cohort Studies. BMJ 2013, 346, e7492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Health Estimates 2020. Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2019. In Global Health Estimates; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics South Africa. Mortality and Causes of Death in South Africa; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

- Kengne, A.P.; Mayosi, B.M. Readiness of the Primary Care System for Non-Communicable Diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, e247–e248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global Nutrition Transition and the Pandemic of Pbesity in Developing Countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Du, S.; Green, W.D.; Beck, M.A.; Algaith, T.; Herbst, C.H.; Alsukait, R.F.; Alluhidan, M.; Alazemi, N.; Shekar, M. Individuals with Obesity and COVID-19: A Global Perspective on the Epidemiology and Biological Relationships. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Africa Department of Health. South Africa Demographic and Health Survey 2016; South Africa Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019.

- Oni, T.; Assah, F.; Erzse, A.; Foley, L.; Govia, I.; Hofman, K.J.; Lambert, E.V.; Micklesfield, L.K.; Shung-King, M.; Smith, J. The Global Diet and Activity Research (GDAR) Network: A Global Public Health Partnership to Address Upstream NCD Risk Factors in Urban Low and Middle-Income Contexts. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shung-King, M.; Weimann, A.; McCreedy, N.; Tatah, L.; Mapa-Tassou, C.; Muzenda, T.; Govia, I.; Were, V.; Oni, T. Protocol for a Multi-Level Policy Analysis of Non-Communicable Disease Determinants of Diet and Physical Activity: Implications for Low-and Middle-Income Countries in Africa and the Caribbean. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2021, 18, 13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Guideline: Sugar Intake for Adults and Children; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, P.; Kelly, S. Effect on Caries of Restricting Sugars Intake: Systematic Review to Inform WHO Guidelines. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of the Witwatersrand. Facts about Sugar-Sweetened Beverages (SSBs) and Obesity in South Africa. Available online: https://www.wits.ac.za/news/latest-news/research-news/2016/2016-04/ssb-tax-home/sugar-facts/ (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- Hattersley, L.; Thiebaud, A.; Fuchs, A.; Gonima, A.; Silver, L.; Mandeville, K. Taxes on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, S.A.; Kruger, P.; Hofman, K. Industry Strategies in the Parliamentary Process of Adopting a Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax in South Africa: A Systematic Mapping. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South Africa Department of Trade and Industry. South African Sugarcane Value Chain Master Plan to 2030; South Africa Department of Trade and Industry: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020.

- Obesity Hub Evidence. Countries That Have Taxes on Sugar-Sweetened Beverages. Available online: https://www.obesityevidencehub.org.au/collections/prevention/countries-that-have-implemented-taxes-on-sugar-sweetened-beverages-ssbs (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Department of Health South Africa. Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Obesity in South Africa 2015–2020; Department of Health South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2015.

- Gilson, L.; Raphaely, N. The Terrain of Health Policy Analysis in Low and Middle Income Countries: A Review of Published Literature 1994–2007. Health Policy Plan. 2008, 23, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolowitz, D.; Marsh, D. Who Learns What from Whom: A Review of the Policy Transfer Literature. Polit. Stud. 1996, 44, 343–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolowitz, D.P.; Marsh, D. Learning from Abroad: The Role of Policy Transfer in Contemporary Policy-Making. Governance 2000, 13, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. Policy Transfer in Critical Perspective. Policy Stud. J 2009, 30, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. International Policy Transfer: Between Global and Sovereign and Between Global and Local. In The Oxford Handbook of Global Policy and Transnational Administration; Oxford Univeristy Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Walt, G.; Shiffman, J.; Schneider, H.; Murray, S.F.; Brugha, R.; Gilson, L. ‘Doing’ Health Policy Analysis: Methodological and Conceptual Reflections and Challenges. Health Policy Plan 2008, 23, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carriedo, A.; Koon, A.D.; Encarnación, L.M.; Lee, K.; Smith, R.; Walls, H. The Political Economy of Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Taxation in Latin America: Lessons from Mexico, Chile and Colombia. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thow, A.M.; Quested, C.; Juventin, L.; Kun, R.; Khan, A.N.; Swinburn, B. Taxing Soft Drinks in the Pacific: Implementation Lessons for Improving Health. Health Promot. Int. 2011, 26, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Africa. Regional Oral Health Strategy 2016–2025: Addressing Oral Diseases as Part of Non-Communicable Diseases; Regional Committee for Africa: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- South Africa Department of Health. Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Obesity in South Africa 2015–2020; South Africa Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016.

- Western Cape Government. Household Food and Nutrition Security Strategic Framework; Western Cape Government: Cape Town, South Africa, 2016.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Compendium of Public Health Strategies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. FAO’s Proposed Follow-Up to the Report of the Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation on Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases COAG/2004/3; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme Codex Committee on Food Labelling Fortieth Session; Food and Agriculture Organization: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Fiscal Policies for Diet and Prevention of Noncommunicable Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Health Taxes; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Fifty-Seventh World Health Assembly WHA57/2004/REC/1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme Codex Committee on Food Labelling Thirth-Fifth Session CX/FL 07/35/3; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization. Codex Alimentarius Food Labelling; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Buse, K.; Mays, N.; Walt, G. Making Health Policy (Understanding Public Health); Bell & Brain Ltd.: Glasgow, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- South Africa Department of Health. Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, 1972 (Act 54 of 1972) Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs (R. 146); South Africa Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2010.

- South Africa Department of Health. Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, 1972 (Act 54 of 1972) Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs: Amendment; South Africa Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014.

- Skikuka, W. Inconsistent Participation of Southern African Countries at Codex; Global Agricultural Information Network, USDA Foreign Agricultural Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council. United Nations Inter-Agency Task Force on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases E/2017/54; United Nations Economic and Social Council: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Traill, W.B. Transnational Corporations, Food Systems and their Impacts on Diets in Developing Countries; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- BEVSA. Beverage Association of South Africa Written Submission to Standing Committee on Finance and Portfolio Committee on Health on the Proposed Taxation of Sugar Sweetened Beverages 26th May 2017; BEVSA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Sixty-Sixth World Health Assembly WHA66/2013/REC/1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Seventieth World Health Assembly WHA70/2017/REC/1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Status of Implementation of the Four Time-Bound Commitments of NCDs; World Health Organization: Brazzaville, Republic of Congo, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Seventy-First World Health Assembly WHA71/2018/REC/1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Sixty–First World Health Assembly WHA61/2008/REC/1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Disease: Report of the Secretary–General; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children; 9241500212; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Sixty-Third World Health Assembly WHA63/2010/REC/1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vorster HH, B.J.; Venter, C.S. Food-Based Dietary Guidelines for South Africa. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 26, S5–S12. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. World Health Assembly First Special Session; WHASS1/2006–WHA60/2007/REC/1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Note by the Secretary-General Transmitting the Report of the Director-General of the World Health Organization on Options for Strengthening and Facilitating Multisectoral Action for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases through Effective Partnership; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases A/RES/66/2; United Nations General Assembly: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- South Africa Department of Health. South African Declaration on the Prevention and Control of Diseases; South Africa Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011.

- South Africa Department of Health. Strategic plan for the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases 2013–17; South Africa Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012.

- South Africa Department of Health. Draft Guidelines Regulations Governing the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs, R642 of 20 July 2007; South Africa Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2007.

- South African Department of Health. Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act, 1972 (Act 54 of 1972) Regulations Relating to the Labelling and Advertising of Foodstuffs (No. R. 642); South Africa Department of Health: Pretoria, South Africa, 2007.

- Mills, L. Considering the Best Interests of the Child when Marketing Food to Children: An Analysis of the South African Regulatory Framework; Stellenbosch University: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, R. Lesson-Drawing in Public policy: A Guide to Learning Across Time and Space; CQ Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Newmark, A.J. An Integrated Approach to Policy Transfer and Diffusion. Rev. Policy Res. 2002, 19, 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African National Treasury. Rates and Monetary Amounts and Amendment of Revenue Laws Bill 26 of 2017; South African National Treasury: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Guidelines for the Use of Nutrition and Health claims (CAC/GL 23-1997); Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- South Africa National Treasury. Taxation of Sugar Sweetened Beverages Policy Paper; South African National Treasury: Pretoria, South Africa, 2016.

- South African Revenue Services (SARS). Excise External Policy Health Promotion Levy on Sugary Beverages; South African Revenue Services (SARS): Pretoria, South Africa, 2020.

- Shisana, O. The South African National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: SANHANES-1; HSRC Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, C.; Watson, F. Incentives and Disincentives for Reducing Sugar in Manufactured Foods; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Basic Documents; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Basic Texts; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roubal, T. Role of WHO in South Africa SSB Tax Initiative; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, D. Transfer and Translation of Policy. Policy Stud. J. 2012, 33, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.T.; Franco-Arellano, B.; Schermel, A.; Labonté, M.-È.; L’Abbé, M.R. Healthfulness and Nutritional Composition of Canadian Prepackaged Foods With and Without Sugar Claims. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2017, 42, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South African National Treasury and Revenue Services (SARS). Final Response Document on the 2017 Rates and Monetary Amounts and Amendment fo Revenue Laws Bill—Health Promotion Levy, 2017; South African National Treasury and Revenue Services (SARS): Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

- Karim, S.A.; Erzse, A.; Thow, A.-M.; Amukugo, H.J.; Ruhara, C.; Ahaibwe, G.; Asiki, G.; Mukanu, M.M.; Ngoma, T.; Wanjohi, M. The Legal Feasibility of Adopting a Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Tax in Seven Sub-Saharan African Countries. Glob. Health Action 2021, 14, 1884358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinan, K.M.; Majija, L.; Cotter, T.; Kotov, A.; Mullin, S.; Murukutla, N. Lessons from South Africa’s Campaign for a Tax on Sugary Beverages; Vital Strategies: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- May, J.; Witten, C.; Lake, L. South African Child Gauge 2020. Food and Nutrition Security; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- South Africa Coordination Committee and Department of Planning; Monitoring and Evaluation (DPME). National Food and Nutrition Security Plan 2018–2023; South Africa Coordination Committee and Department of Planning: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017.

| Policy Transfer Framework Questions | Evident from the Policy Analysis |

|---|---|

| Who is involved in the policy transfer process and why engage in transfer? | International organizations, national government and private sector (food and beverage industry) |

| Where are policy directives drawn from? | Global recommendations from the WHO/Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) and Codex Alimentarius (the ‘Codex’) |

| What elements of policy are transferred? | Policy ideas organized by three themes: the problem frame, suggested approaches (multisectoral/cost-effective) for addressing the problem of unhealthy diets and high sugar intake and policy options |

| What are the different degrees of transfer? | Mostly policy dictates are emulated nationally, and very occasionally some wording is copied |

| What restricts or facilitates the policy transfer process? | Private sector interference, skills capacity and policy expertise within government can constrain policy transfer, while international organizations actions help facilitate it |

| Source | Textual Quote |

|---|---|

| Global United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). UNIATF on the Prevention and Control of NCDs E/2017/54 | “Private sector interference that blocks governments in their efforts to implement certain very cost-effective and affordable measures to attain target 3.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals (for example, increasing excise taxes and prices on tobacco products, alcoholic beverages and sugar-sweetened beverages)” [42]. |

| WHO, Montevideo Roadmap 2018–2030 on NCDs as a Sustainable Development Priority, WHA71.2 Annex, 2018 | ”One obstacle at country level is the lack of capacity to effectively address public health goals when they are in conflict with private sector interests, in order to effectively leverage the roles and contributions of the diverse range of stakeholders in combatting NCDs” [48]. |

| Africa Region WHO Regional Office for Africa. Status of Implementation of the Four Time-bound Commitments of NCDs | “Tackling NCD risk factors in the region is hampered by the interference of the tobacco, alcohol and food industries” [47]. |

| Global WHO Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity, and Health (2004) Policy Recommendations and Examples for Member States | National South African and Western Cape Corresponding policies Addressing Unhealthy Diets and High Sugar Intake |

|---|---|

| National strategies, policies and action plans need broad support | |

|

|

| Governments should provide accurate and balanced information | |

|

|

| National food and agricultural policies should be consistent with the protection and promotion of public health | |

|

|

| School policies and programs should support the adoption of healthy diets and physical activity |

|

| Source | Textual Quote |

|---|---|

| Global 2004 WHO Global Strategy | “The term ‘free sugars’ refers to all monosaccharides and disaccharides added to foods by the manufacturer, cook or consumer, plus sugars naturally present in honey, syrups and fruit juices” [35]. |

| National South African FBDG-2013 | “Definition of ‘added sugars’ means any sugar added to foods during processing, and includes but is not limited to: mono and disaccharides (sugars), honey, molasses, sucrose with added molasses, coloured sugar, fruit juice concentrate, deflavoured and/or deionised fruit juice and concentrates thereof, fruit nectar, fruit and vegetable pulp, dried fruit paste, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), malt or any other syrup of various origins, whey powder, milk solids or any derivative thereof” [53]. |

| Source | Textual quote |

|---|---|

| Global Codex guidelines for use of nutrition and health claims, CAC/GL 23-1997 | “Non-addition of sugars Claims regarding the non-addition of sugars to a food may be made, provided the following conditions are met: Claims (a) No sugars of any type have been added to the food (examples: sucrose, glucose, honey, molasses, corn syrup, etc.); (b) The food contains no ingredients that contain sugars as an ingredient (Examples: jams, jellies, sweetened chocolate, sweetened fruit pieces, etc.)” |

| National South African regulations relating to the labelling and advertising of foods, 2014 (No. R. 429) | “Non-addition claims for sugar(s) (iii) Claims regarding the non-addition of sugars to a food may be made, provided the following conditions are met: (aa) the food contains no ingredients that contain sugars as part of an ingredient, such as, but not limited to, jams, jellies, sweetened chocolate, sweetened fruit pieces” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCreedy, N.; Shung-King, M.; Weimann, A.; Tatah, L.; Mapa-Tassou, C.; Muzenda, T.; Govia, I.; Were, V.; Oni, T. Reducing Sugar Intake in South Africa: Learnings from a Multilevel Policy Analysis on Diet and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811828

McCreedy N, Shung-King M, Weimann A, Tatah L, Mapa-Tassou C, Muzenda T, Govia I, Were V, Oni T. Reducing Sugar Intake in South Africa: Learnings from a Multilevel Policy Analysis on Diet and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811828

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCreedy, Nicole, Maylene Shung-King, Amy Weimann, Lambed Tatah, Clarisse Mapa-Tassou, Trish Muzenda, Ishtar Govia, Vincent Were, and Tolu Oni. 2022. "Reducing Sugar Intake in South Africa: Learnings from a Multilevel Policy Analysis on Diet and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811828

APA StyleMcCreedy, N., Shung-King, M., Weimann, A., Tatah, L., Mapa-Tassou, C., Muzenda, T., Govia, I., Were, V., & Oni, T. (2022). Reducing Sugar Intake in South Africa: Learnings from a Multilevel Policy Analysis on Diet and Noncommunicable Disease Prevention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811828