Number of Births and Later-Life Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome Variable

2.2.2. Explanatory Variable

2.2.3. Control Variable

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Characteristics of the Participants

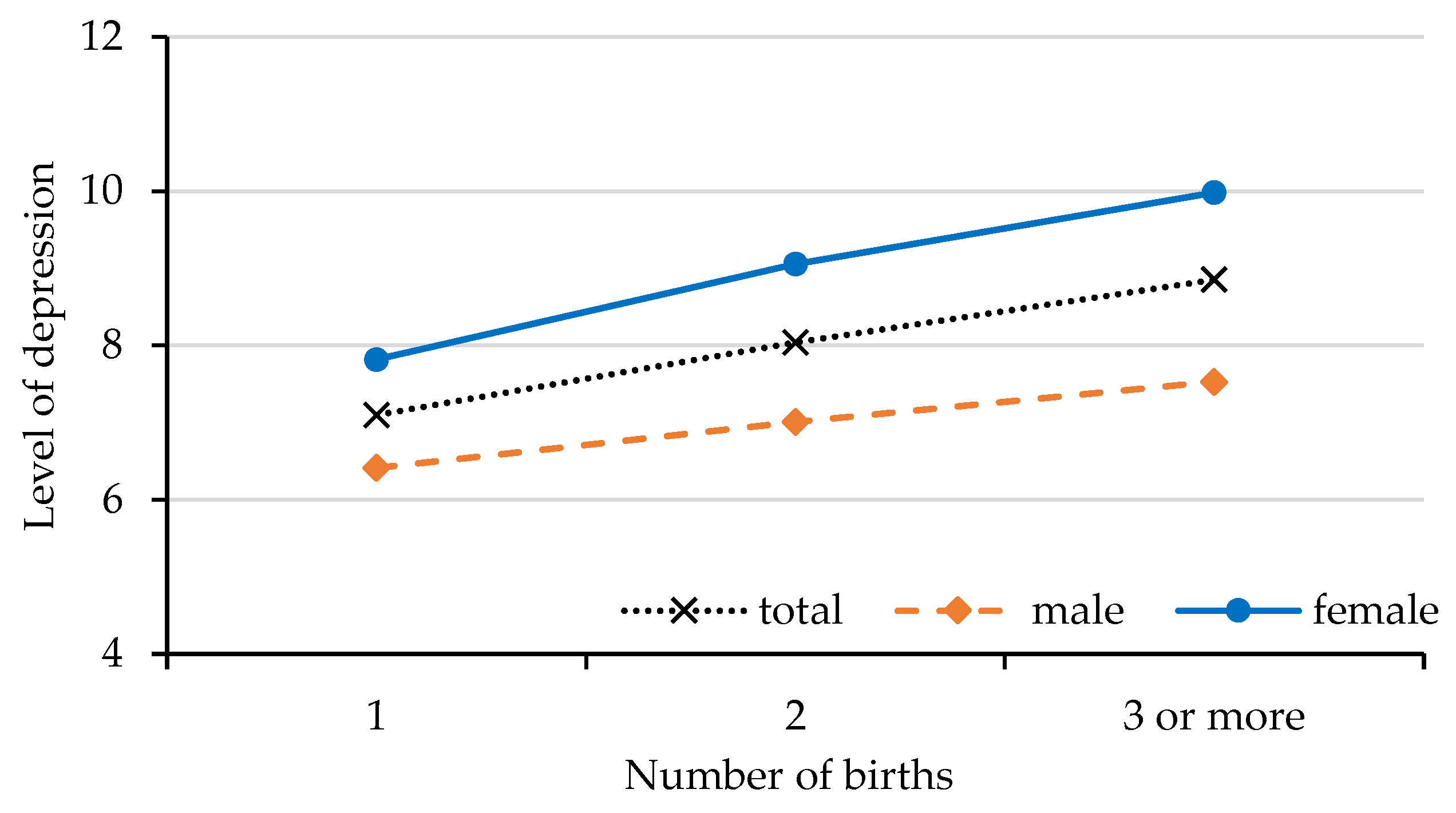

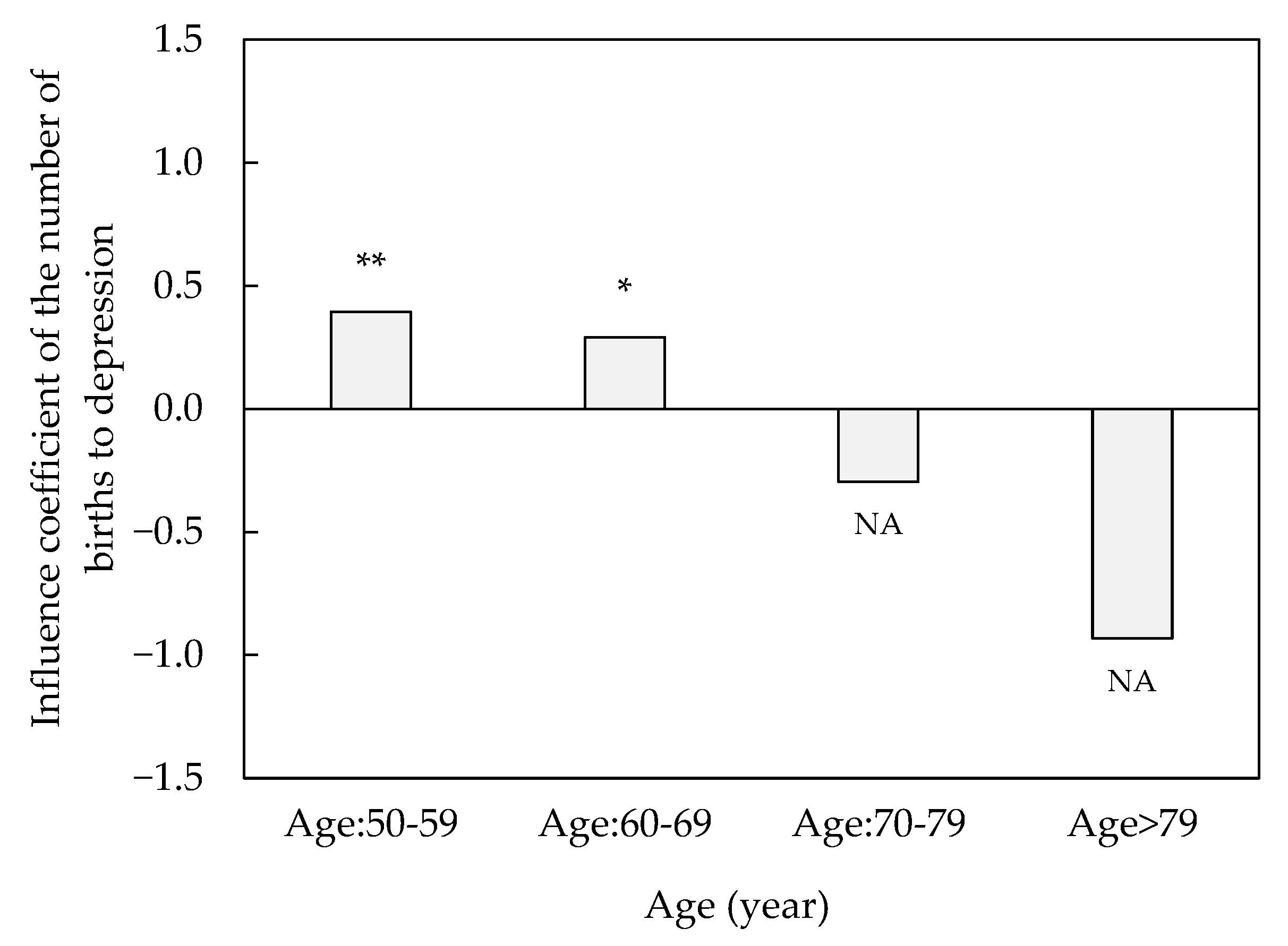

3.2. The Relationship between Number of Births and Depression

3.3. The Relationship between the Proportion of Sons and Depression

3.4. The Relationship between Abortion and Depression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grundy, E.; Kravdal, Ø. Fertility History and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Register-Based Analysis of Complete Cohorts of Norwegian Women and Men. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundy, E.; Tomassini, C. Fertility History and Health in Later Life: A Record Linkage Study in England and Wales. Soc. Sci. Med. 2005, 61, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, N.J. The Long-Term Consequences of Childbearing: Physical and Psychological Well-Being of Mothers in Later Life. Res. Aging 2008, 30, 722–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, E.P. Childbearing and Obesity in Women: Weight Before, During, and After Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. 2009, 36, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.A.; Yang, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Bian, Z.; Millwood, I.Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, L.; Hu, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Parenthood and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases among 0.5 Million Men and Women: Findings from the China Kadoorie Biobank. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Flaherty, M.; Baxter, J.; Haynes, M.; Turrell, G. The Family Life Course and Health: Partnership, Fertility Histories, and Later-Life Physical Health Trajectories in Australia. Demography 2016, 53, 777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barclay, K.; Keenan, K.; Grundy, E.; Kolk, M.; Myrskylä, M. Reproductive History and Post-Reproductive Mortality: A Sibling Comparison Analysis Using Swedish Register Data. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 155, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, N.I.; Cnattingius, S.; Dickman, P.W.; Mittleman, M.A.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Ingelsson, E. Parity and Risk of Later-Life Maternal Cardiovascular Disease. Am. Heart J. 2010, 159, 215–221.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, D.L. Explaining the Curvilinear Relationship between Age at First Birth and Depression among Women. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keizer, R.; Dykstra, P.A.; Poortman, A.-R. The Transition to Parenthood and Well-Being: The Impact of Partner Status and Work Hour Transitions. J. Fam. Psychol. 2010, 24, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, S.L.; Grundy, E.M.D. Fertility History and Cognition in Later Life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2017, 72, 1021–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yang, H.; Xie, L.; Zhang, A.; Lin, X.; Nie, Y.; Zhang, X. Effects of Fertility Behaviors on Depression Among the Elderly: Empirical Evidence From China. Front. Public Health 2021, 8, 570832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; He, F.; Sun, Q.; Li, Q.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Lin, J. Reproductive History and Risk of Depressive Symptoms in Postmenopausal Women: A Cross-Sectional Study in Eastern China. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 246, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lee, S.G.; Shin, J.; Choi, Y.; Park, E.-C. The Effect of Offspring on Depressive Disorder among Old Adults: Evidence from the Korean Longitudinal Study of Aging from 2006 to 2012. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 61, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, E.M.D.; Read, S.; Väisänen, H. Fertility Trajectories and Later-Life Depression among Parents in England. Popul. Stud. 2019, 74, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.; Han, J.; Yi, C. The Health Effect of the Number of Children on Chinese Elders: An Analysis Based on Hukou Category. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 700024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djundeva, M.; Emery, T.; Dykstra, P.A. Parenthood and Depression: Is Childlessness Similar to Sonlessness among Chinese Seniors? Ageing Soc. 2018, 38, 2097–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Xu, X. Are Daughters No Inferior to Sons? The Double Gender Differences in Fertility Behavior Which Can Affect Happiness. Nankai Econ. Stud. 2018, 3, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildingsson, I.; Thomas, J. Parental Stress in Mothers and Fathers One Year after Birth. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2014, 32, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykstra, P.A.; Wagner, M. Pathways to Childlessness and Late-Life Outcomes. J. Fam. Issues 2007, 28, 1487–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.; Slagsvold, B.; Moum, T. Childlessness and Psychological Well-Being in Midlife and Old Age: An Examination of Parental Status Effects Across a Range of Outcomes. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 94, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, W. Abortion and Depression: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study of Young Women. Scand. J. Public Health 2008, 36, 424–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutel, M.; Deckardt, R.; Schaudig, K.; Franke, S.; Zauner, R. Grief, depression and anxiety after spontaneous abortion--a study of systematic evaluation and factors of influence. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 1992, 42, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xiang, Y.-T.; Yu, X.; Sartorius, N.; Ungvari, G.S.; Chiu, H.F.K. Mental Health in China: Challenges and Progress. Lancet 2012, 380, 1715–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Hesketh, T. The Effects of China’s Universal Two-Child Policy. Lancet 2016, 388, 1930–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.Y.; Wu, W.H. Transmutation of Population Fertility Concepts and Social Development. Seeker 2008, 28, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.; Xiao, R. The Relationship among Raising Children for Old Age, More Sons More Happiness and Pension Tendency of Rural Elderly. Chongqing Soc. Sci. 2016, 1, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Strauss, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Gong, J.; Meng, Q.; Wang, G.; Wang, H. China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study Wave 4 User’s Guide; National School of Development, Peking University: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen, E.M.; Malmgren, J.A.; Carter, W.B.; Patrick, D.L. Screening for Depression in Well Older Adults: Evaluation of a Short Form of the CES-D. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1994, 10, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fang, X. Internal Migration Experience and Depressive Symptoms among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 19, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XU, Q. Living Arrangement and Depression among the Chinese Elderly People: An Empirical Study Based on CHARLS. Sociol. Rev. China 2018, 6, 47–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Xin, T.; Tang, K. Number of Children and the Prevalence of Later-Life Major Depression and Insomnia in Women and Men: Findings from a Cross-Sectional Study of 0.5 Million Chinese Adults. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, L.; Pike, M.C.; Ross, R.K.; Judd, H.L.; Brown, J.B.; Henderson, B.E. Estrogen and Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin Levels in Nulliparous and Parous Women2. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1985, 74, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomassini, C.; Kalogirou, S.; Grundy, E.; Fokkema, T.; Martikainen, P.; Broese van Groenou, M.; Karisto, A. Contacts between Elderly Parents and Their Children in Four European Countries: Current Patterns and Future Prospects. Eur. J. Ageing 2004, 1, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | Total | Male | Female | Differences in Mean | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Degree of depression | −2.44 *** | ||||||

| 0–5 | 3898 | 38.38 | 1808 | 47.79 | 2090 | 32.79 | |

| 6–11 | 3436 | 33.83 | 1273 | 33.65 | 2163 | 33.94 | |

| 12–17 | 1746 | 17.19 | 469 | 12.40 | 1277 | 20.04 | |

| 18–23 | 802 | 7.90 | 197 | 5.21 | 605 | 9.49 | |

| 24–30 | 274 | 2.70 | 36 | 0.95 | 238 | 3.73 | |

| Number of births | −0.10 *** | ||||||

| 1 | 1126 | 11.09 | 478 | 12.64 | 648 | 10.17 | |

| 2 | 3203 | 31.54 | 1317 | 34.81 | 1886 | 29.59 | |

| 3 or more | 5827 | 57.37 | 1988 | 52.55 | 3839 | 60.24 | |

| Number of abortions | 0.02 | ||||||

| 0 | 7661 | 75.43 | 2804 | 74.12 | 4857 | 76.21 | |

| 1 | 2175 | 21.42 | 872 | 23.05 | 1303 | 20.45 | |

| 2 | 301 | 2.96 | 97 | 2.56 | 204 | 3.20 | |

| 3 or more | 19 | 0.19 | 10 | 0.26 | 9 | 0.14 | |

| Number of sons | −0.10 *** | ||||||

| 0 | 1230 | 12.11 | 511 | 13.51 | 719 | 11.28 | |

| 1 | 4218 | 41.53 | 1607 | 42.48 | 2611 | 40.97 | |

| 2 | 3057 | 30.10 | 1157 | 30.58 | 1900 | 29.81 | |

| 3 or more | 1651 | 16.26 | 508 | 13.43 | 1143 | 17.94 | |

| Age (year) | −0.05 * | ||||||

| 50–59 | 2705 | 26.63 | 1001 | 26.46 | 1704 | 26.74 | |

| 60–69 | 4523 | 44.54 | 1756 | 46.42 | 2767 | 43.42 | |

| 70–79 | 2353 | 23.17 | 864 | 22.84 | 1489 | 23.36 | |

| >79 | 575 | 5.66 | 162 | 4.29 | 413 | 6.48 | |

| Spouse status | 0.29 *** | ||||||

| Not available | 2436 | 23.99 | 209 | 5.52 | 2227 | 34.94 | |

| Available | 7720 | 76.01 | 3574 | 94.48 | 4146 | 65.06 | |

| Residential area | 0.01 | ||||||

| Rural | 6450 | 63.51 | 2378 | 62.86 | 4072 | 63.89 | |

| Urban | 3706 | 36.49 | 1405 | 37.14 | 2301 | 36.11 | |

| Educational status | 0.11 *** | ||||||

| Less than lower secondary | 9263 | 91.21 | 3227 | 85.30 | 6036 | 94.71 | |

| Upper secondary and vocational training | 789 | 7.77 | 482 | 12.74 | 307 | 4.82 | |

| Tertiary | 104 | 1.02 | 74 | 1.96 | 30 | 0.47 | |

| Financial assets | 0.10 *** | ||||||

| Below average | 7303 | 71.91 | 2481 | 65.58 | 4822 | 75.66 | |

| Average or above average | 2853 | 28.09 | 1302 | 34.42 | 1551 | 24.34 | |

| Work status | 0.15 *** | ||||||

| No | 4319 | 42.53 | 1250 | 33.04 | 3069 | 48.16 | |

| Yes | 5837 | 57.47 | 2533 | 66.96 | 3304 | 51.84 | |

| Pension | −0.02 *** | ||||||

| No | 3586 | 35.31 | 1386 | 36.64 | 2200 | 34.52 | |

| Yes | 6570 | 64.69 | 2397 | 63.36 | 4173 | 65.48 | |

| Cohabitation with children | −0.03 *** | ||||||

| No | 5675 | 55.88 | 2196 | 58.05 | 3479 | 54.59 | |

| Yes | 4481 | 44.12 | 1587 | 41.95 | 2894 | 45.41 | |

| Drinking status | 0.40 *** | ||||||

| No | 7283 | 71.71 | 1757 | 46.44 | 5526 | 86.71 | |

| Yes | 2873 | 28.29 | 2026 | 53.56 | 847 | 13.29 | |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| No | 7945 | 78.23 | 1914 | 50.59 | 6031 | 94.63 | 0.44 *** |

| Yes | 2211 | 21.77 | 1869 | 49.41 | 342 | 5.37 | |

| Psychological treatment (lagged one period) | |||||||

| No | 10,139 | 99.83 | 3778 | 99.87 | 6361 | 99.81 | −0.00 |

| Yes | 17 | 0.17 | 5 | 0.13 | 12 | 0.19 | |

| Year | |||||||

| 2013 | 2328 | 22.92 | 599 | 15.83 | 1729 | 27.13 | 0.43 *** |

| 2015 | 3811 | 37.52 | 1525 | 40.31 | 2286 | 35.87 | |

| 2018 | 4017 | 39.55 | 1659 | 43.85 | 2358 | 37 | |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |

| β (S.E) | β (S.E) | β (S.E) | |

| Number of births | 0.245 ** (0.117) | −0.059 (0.163) | 0.386 ** (0.160) |

| Age | −0.020 * (0.011) | 0.032 * (0.017) | −0.031 ** (0.014) |

| Spouse status | −1.191 *** (0.176) | −0.787 ** (0.375) | −0.799 *** (0.221) |

| Residential area | −1.421 *** (0.162) | −1.276 *** (0.229) | −1.529 *** (0.219) |

| Educational status | −1.294 *** (0.227) | −1.069 *** (0.255) | −0.937 ** (0.397) |

| Financial assets | −0.205 *** (0.021) | −0.140 *** (0.032) | −0.227 *** (0.027) |

| Work status | −0.331 ** (0.137) | −0.429 ** (0.212) | −0.160 (0.176) |

| Pension | 0.222 (0.137) | 0.259 (0.210) | 0.119 (0.177) |

| Cohabitation with children | −0.164 (0.123) | 0.334 * (0.180) | −0.420 ** (0.163) |

| Drinking status | −0.788 *** (0.149) | −0.624 *** (0.189) | −0.008 (0.243) |

| Smoking status | −0.430 ** (0.171) | 0.365 * (0.196) | 0.777 * (0.408) |

| Psychological treatment (lagged one period) | 2.476 * (1.382) | 0.752 (2.409) | 3.040 * (1.690) |

| Abortion history | 0.425 ** (0.172) | 0.234 (0.241) | 0.473 ** (0.235) |

| Constant | 13.855 *** (0.798) | 8.676 *** (1.242) | 14.133 *** (1.103) |

| Observations | 10,156 | 3783 | 6373 |

| Variables | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |

| β (S.E) | β (S.E) | β (S.E) | |

| Proportion of sons | −0.302 (0.234) | −0.643 ** (0.323) | −0.013 (0.323) |

| Age | −0.013 (0.010) | 0.030 * (0.016) | −0.019 (0.014) |

| Spouse status | −1.192 *** (0.176) | −0.793 ** (0.375) | −0.787 *** (0.221) |

| Residential area | −1.476 *** (0.160) | −1.261 *** (0.226) | −1.610 *** (0.217) |

| Educational status | −1.344 *** (0.226) | −1.074 *** (0.255) | −1.056 *** (0.395) |

| Financial assets | −0.209 *** (0.021) | −0.137 *** (0.032) | −0.232 *** (0.027) |

| Work status | −0.317 ** (0.137) | −0.421 ** (0.212) | −0.150 (0.176) |

| Pension | 0.216 (0.137) | 0.267 (0.210) | 0.108 (0.177) |

| Cohabitation with children | −0.146 (0.123) | 0.336 * (0.180) | −0.401 ** (0.163) |

| Drinking status | −0.794 *** (0.149) | −0.612 *** (0.188) | 09 (0.243) |

| Smoking status | −0.439 ** (0.171) | 0.369 * (0.196) | 0.782 * (0.408) |

| Psychological treatment (lagged one period) | 2.472 * (1.382) | 0.701 (2.407) | 2.959 * (1.690) |

| Abortion history | 0.392 ** (0.172) | 0.222 (0.240) | 0.436 * (0.235) |

| Constant | 14.240 *** (0.803) | 8.993 *** (1.249) | 14.524 *** (1.106) |

| Observations | 10,156 | 3783 | 6373 |

| Variables | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | |

| β (S.E) | β (S.E) | β (S.E) | |

| Number of abortions | 0.329 ** (0.142) | 0.078 (0.202) | 0.422 ** (0.192) |

| Age | −0.013 (0.010) | 0.030 * (0.016) | −0.019 (0.014) |

| Spouse status | −1.188 *** (0.176) | −0.789 ** (0.375) | −0.785 *** (0.221) |

| Residential area | −1.475 *** (0.160) | −1.246 *** (0.227) | −1.615 *** (0.217) |

| Educational status | −1.339 *** (0.226) | −1.050 *** (0.254) | −1.060 *** (0.394) |

| Financial assets | −0.209 *** (0.021) | −0.137 *** (0.032) | −0.232 *** (0.027) |

| Work status | −0.321 ** (0.137) | −0.437 ** (0.212) | −0.148 (0.176) |

| Pension | 0.215 (0.137) | 0.260 (0.210) | 0.105 (0.177) |

| Cohabitation with children | −0.151 (0.123) | 0.324* (0.180) | −0.400 ** (0.163) |

| Drinking status | −0.789 *** (0.149) | −0.617 *** (0.188) | 0.011 (0.243) |

| Smoking status | −0.439 ** (0.171) | 0.369 * (0.196) | 0.767 * (0.408) |

| Psychological treatment (lagged one period) | 2.469 * (1.382) | 0.794 (2.408) | 2.941 * (1.690) |

| Constant | 14.085 *** (0.792) | 8.656 *** (1.236) | 14.511 *** (1.092) |

| Observations | 10,156 | 3783 | 6373 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, K.; Nie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Z. Number of Births and Later-Life Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811780

Xue K, Nie Y, Wang Y, Hu Z. Number of Births and Later-Life Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811780

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Kaiyun, Yafeng Nie, Yue Wang, and Zhen Hu. 2022. "Number of Births and Later-Life Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811780

APA StyleXue, K., Nie, Y., Wang, Y., & Hu, Z. (2022). Number of Births and Later-Life Depression in Older Adults: Evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811780