Which Structural Interventions for Adolescent Contraceptive Use Have Been Evaluated in Low- and Middle-Income Countries?

Abstract

1. Introduction

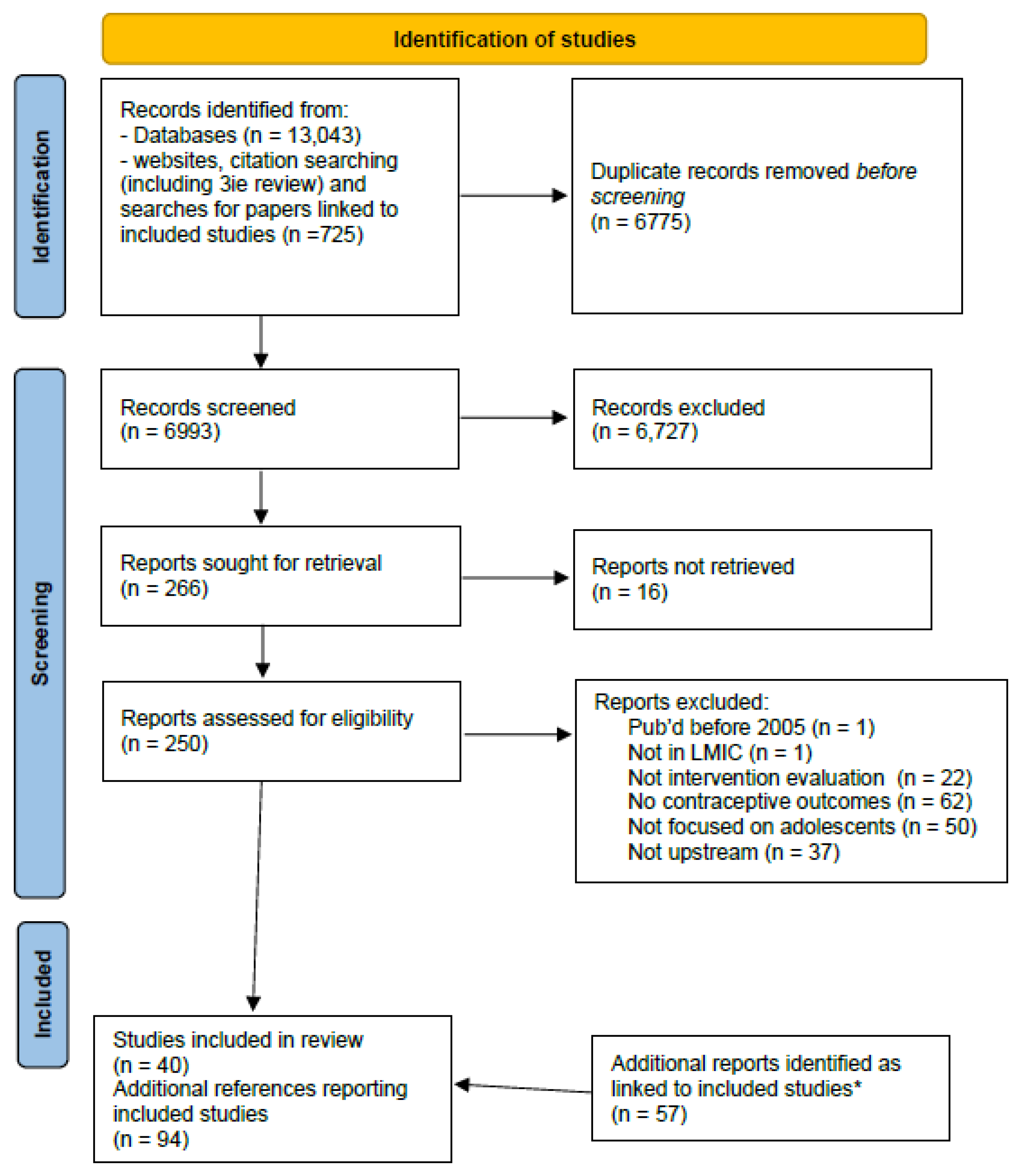

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Aims of the Interventions

3.2. Type of Structural Interventions

3.3. Who Was Targeted by the Intervention?

3.4. Evaluations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Search Strategy

- Databases searched

- OvidSP Medline ALL, 1946 to 27 July 2020.

- OvidSP Embase, 1947 to 29 July 2020.

- OvidSP Global Health, 1910 to 2020 week 29.

- Ebsco CINAHL Plus, complete database to search date.

- Ebsco Africa-Wide Information, complete database to search date.

- Clarivate Analytics Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded. Year 1970–present, data last updated 16 September 2020.

- ProQuest ERIC, 1966–search date.

- WHO Global Index Medicus, complete database to search date.

- Websites hand-searched

| 1. Advocates for Youth |

| 2. Family Health International |

| 3. Guttmacher Institute |

| 4. Interagency Youth Working Group |

| 5. International Center for Research on Women |

| 6. International Planned Parenthood Federation |

| 7. Family planning high-impact practices |

| 8. Marie Stopes International |

| 9. Pathfinder International |

| 10. Population Council |

| 11. United Nations Population Fund |

| 12. United Nations Children’s Fund |

| 13. World Health Organisation (WHO) |

| 14. NBER |

| 15. World Bank (2016 onwards) |

| 16. JSI (2016 onwards) |

- Example search strategy: Medline OvidSP

- 1.

- adolescent/or child/ (2806512)

- 2.

- puberty/or menarche/ (17517)

- 3.

- homeless youth/ (1290)

- 4.

- minors/ (2576)

- 5.

- disabled children/ (6288)

- 6.

- students/ (58686)

- 7.

- child *.ti,ab. (1383127)

- 8.

- (girl or girls or boy or boys).ti,ab. (229162)

- 9.

- (paediatric * or pediatric *).ti,ab. (350866)

- 10.

- (schoolage * or (school adj1 age *)).ti,ab. (22762)

- 11.

- minor *.ti,ab. (295741)

- 12.

- ((school or college) adj3 (pupil * or student *)).ti,ab. (46075)

- 13.

- prepubescen *.ti,ab. (1008)

- 14.

- puberty.ti,ab. (27560)

- 15.

- pubescent *.ti,ab. (865)

- 16.

- adolescen *.ti,ab. (278039)

- 17.

- juvenil *.ti,ab. (81699)

- 18.

- underage *.ti,ab. (1211)

- 19.

- (preteen * or pre-teen *).ti,ab. (481)

- 20.

- (teen or teens or teener).ti,ab. (10684)

- 21.

- teenage *.ti,ab. (21165)

- 22.

- (youth or youths).ti,ab. (72797)

- 23.

- young people *.ti,ab. (28285)

- 24.

- young person *.ti,ab. (3499)

- 25.

- young wom#n.ti,ab. (30614)

- 26.

- (young man or young men).ti,ab. (20422)

- 27.

- (highschool or (high adj1 school *)).ti,ab. (32452)

- 28.

- sophomore *.ti,ab. (708)

- 29.

- (university adj3 student *).ti,ab. (19647)

- 30.

- (transition adj4 adult *).ti,ab. (4374)

- 31.

- emerging adult *.ti,ab. (2446)

- 32.

- young adult *.ti,ab. (94952)

- 33.

- early adult *.ti,ab. (7360)

- 34.

- freshm?n.ti,ab. (2313)

- 35.

- ((“10” or “11” or “12” or “13” or “14” or “15” or “16” or “17” or “18” or “19”) adj (year* old or year* of age)).ti,ab. (169296)

- 36.

- ((ten or eleven or twelve or thirteen or fourteen or fifteen or sixteen or seventeen or eighteen or nineteen) adj (year * old or year * of age)).ti,ab. (4540)

- 37.

- (age * adj (“10” or “11” or “12” or “13” or “14” or “15” or “16” or “17” or “18” or “19”) adj year *).ti,ab. (36798)

- 38.

- (age * adj (ten or eleven or twelve or thirteen or fourteen or fifteen or sixteen or seventeen or eighteen or nineteen) adj year *).ti,ab. (183)

- 39.

- or/1-38 (3983043)

- 40.

- exp Contraception/ (26828)

- 41.

- Family Planning Services/ (24812)

- 42.

- exp Contraceptive Devices/ (25273)

- 43.

- Contraception Behavior/ (8044)

- 44.

- family planning.ti,ab. (21238)

- 45.

- contracept *.ti,ab. (67679)

- 46.

- ((childbear * or pregnan *) adj2 (avoid * or delay * or prevent * or limit * or space or spacing or timing)).ti,ab. (9890)

- 47.

- or/40-46 (116173)

- 48.

- Developing Countries/ (74803)

- 49.

- ((developing or less * developed or under developed or underdeveloped or middle income or low * income) adj (economy or economies)).ti,ab. (561)

- 50.

- ((developing or less * developed or under developed or underdeveloped or middle income or low * income or underserved or under served or deprived or poor *) adj (countr * or nation? or population? or world)).ti,ab. (101164)

- 51.

- (low * adj (gdp or gnp or gross domestic or gross national)).ti,ab. (247)

- 52.

- (low adj3 middle adj3 countr*).ti,ab. (16855)

- 53.

- (lmic or lmics or third world or lami countr *).ti,ab. (7757)

- 54.

- transitional countr *.ti,ab. (160)

- 55.

- global south.ti,ab. (394)

- 56.

- “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea”/ (229)

- 57.

- (North Korea or (Democratic People * Republic adj2 Korea)).ti,ab. (421)

- 58.

- Cambodia/ (3310)

- 59.

- Cambodia.ti,ab. (3856)

- 60.

- Indonesia/ (10492)

- 61.

- (Indonesia or Dutch East Indies).ti,ab. (12412)

- 62.

- (Kiribati or Gilbert Islands or Phoenix Islands or Line Islands).ti,ab. (244)

- 63.

- Laos/ (1922)

- 64.

- (Laos or (Lao adj1 Democratic Republic)).ti,ab. (1966)

- 65.

- Micronesia/ (1172)

- 66.

- Micronesia.ti,ab. (656)

- 67.

- Mongolia/ (1792)

- 68.

- Mongolia.ti,ab. (4033)

- 69.

- Myanmar/ (2472)

- 70.

- (Myanmar or Burma).ti,ab. (4131)

- 71.

- Papua New Guinea/ (3453)

- 72.

- (Papua New Guinea or German New Guinea or British New Guinea or Territory of Papua).ti,ab. (4504)

- 73.

- Philippines/ (8326)

- 74.

- (Philippines or Philippine Islands).ti,ab. (8346)

- 75.

- Solomon Islands.ti,ab. (805)

- 76.

- Timor-Leste/ (204)

- 77.

- (Timor-Leste or East Timor or Portuguese Timor).ti,ab. (525)

- 78.

- Vanuatu/ (352)

- 79.

- (Vanuatu or New Hebrides).ti,ab. (690)

- 80.

- Vietnam/ (12258)

- 81.

- (Viet Nam or Vietnam or French Indochina).ti,ab. (15137)

- 82.

- American Samoa/ (183)

- 83.

- American Samoa.ti,ab. (362)

- 84.

- exp China/ (193285)

- 85.

- China.ti,ab. (180908)

- 86.

- Fiji/ (944)

- 87.

- Fiji.ti,ab. (1704)

- 88.

- Malaysia/ (15038)

- 89.

- (Malaysia or Malayan Union or Malaya).ti,ab. (16085)

- 90.

- Marshall Islands.ti,ab. (302)

- 91.

- Nauru.ti,ab. (153)

- 92.

- “Independent State of Samoa”/ (247)

- 93.

- ((Samoa not American Samoa) or Western Samoa or Navigator Islands or Samoan Islands).ti,ab. (559)

- 94.

- Thailand/ (26407)

- 95.

- (Thailand or Siam).ti,ab. (26674)

- 96.

- Tonga/ (244)

- 97.

- Tonga.ti,ab. (431)

- 98.

- (Tuvalu or Ellice Islands).ti,ab. (74)

- 99.

- Melanesia/ (1071)

- 100.

- Melanesia.ti,ab. (301)

- 101.

- Polynesia/ (1873)

- 102.

- Polynesia.ti,ab. (1298)

- 103.

- Kyrgyzstan/ (1285)

- 104.

- (Kyrgyzstan or Kyrgyz Republic or Kirghizia or Kirghiz).ti,ab. (980)

- 105.

- Moldova/ (688)

- 106.

- Moldova.ti,ab. (515)

- 107.

- Ukraine/ (15939)

- 108.

- Ukraine.ti,ab. (4675)

- 109.

- Uzbekistan/ (1895)

- 110.

- Uzbekistan.ti,ab. (1104)

- 111.

- Albania/ (839)

- 112.

- Albania.ti,ab. (1051)

- 113.

- Armenia/ (1408)

- 114.

- Armenia.ti,ab. (1044)

- 115.

- Azerbaijan/ (1202)

- 116.

- Azerbaijan.ti,ab. (1353)

- 117.

- “Republic of Belarus”/ (2064)

- 118.

- (Belarus or Byelarus or Byelorussia or Belorussia).ti,ab. (1543)

- 119.

- Bosnia-Herzegovina/ (2121)

- 120.

- (Bosnia or Herzegovina).ti,ab. (2317)

- 121.

- Bulgaria/ (6358)

- 122.

- Bulgaria.ti,ab. (4189)

- 123.

- “Georgia (Republic)”/ (1802)

- 124.

- Georgia.ti,ab. not Georgia/ (5960)

- 125.

- Kazakhstan/ (2665)

- 126.

- (Kazakhstan or Kazakh).ti,ab. (2743)

- 127.

- Kosovo/ (202)

- 128.

- Kosovo.ti,ab. (923)

- 129.

- Montenegro/ (214)

- 130.

- Montenegro.ti,ab. (823)

- 131.

- “Republic of North Macedonia”/ (557)

- 132.

- North Macedonia.ti,ab. (55)

- 133.

- Romania/ (10034)

- 134.

- Romania.ti,ab. (5512)

- 135.

- exp Russia/ (53208)

- 136.

- “Russia (Pre-1917)”/ (5981)

- 137.

- USSR/ (42765)

- 138.

- (Russia or Russian Federation or USSR or Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or Soviet Union).ti,ab. (28150)

- 139.

- Serbia/ (3133)

- 140.

- Serbia.ti,ab. (4315)

- 141.

- Turkey/ (34585)

- 142.

- (Turkey.ti,ab. not animal/) or (Anatolia or Asia Minor).ti,ab. (25104)

- 143.

- Turkmenistan/ (576)

- 144.

- Turkmenistan.ti,ab. (343)

- 145.

- Tajikistan/ (741)

- 146.

- Tajikistan.ti,ab. (580)

- 147.

- Asia, Central/ (475)

- 148.

- Asia, Northern/ (20)

- 149.

- Central Asia.ti,ab. (2269)

- 150.

- Haiti/ (3156)

- 151.

- (Haiti or Hayti).ti,ab. (3035)

- 152.

- Bolivia/ (2571)

- 153.

- Bolivia.ti,ab. (3228)

- 154.

- El Salvador/ (871)

- 155.

- El Salvador.ti,ab. (1237)

- 156.

- Honduras/ (1119)

- 157.

- Honduras.ti,ab. (1737)

- 158.

- Nicaragua/ (1480)

- 159.

- Nicaragua.ti,ab. (1852)

- 160.

- Argentina/ (15692)

- 161.

- (Argentina or Argentine Republic).ti,ab. (16531)

- 162.

- Belize/ (576)

- 163.

- (Belize or British Honduras).ti,ab. (843)

- 164.

- Brazil/ (93168)

- 165.

- Brazil.ti,ab. (82703)

- 166.

- Colombia/ (10376)

- 167.

- Colombia.ti,ab. (12026)

- 168.

- Costa Rica/ (3662)

- 169.

- Costa Rica.ti,ab. (4837)

- 170.

- Cuba/ (5016)

- 171.

- Cuba.ti,ab. (4477)

- 172.

- Dominica/ (98)

- 173.

- Dominica.ti,ab. (472)

- 174.

- Dominican Republic/ (1561)

- 175.

- Dominican Republic.ti,ab. (1887)

- 176.

- Ecuador/ (3711)

- 177.

- Ecuador.ti,ab. (4468)

- 178.

- Grenada/ (142)

- 179.

- Grenada.ti,ab. (314)

- 180.

- Guatemala/ (2966)

- 181.

- Guatemala.ti,ab. (3500)

- 182.

- Guyana/ (683)

- 183.

- (Guyana or British Guiana).ti,ab. (1080)

- 184.

- Jamaica/ (3426)

- 185.

- Jamaica.ti,ab. (3226)

- 186.

- Mexico/ (38352)

- 187.

- (Mexico or United Mexican States).ti,ab. (41958)

- 188.

- Paraguay/ (786)

- 189.

- Paraguay.mp. (1678)

- 190.

- Peru/ (8735)

- 191.

- Peru.ti,ab. (10340)

- 192.

- Saint Lucia/ (69)

- 193.

- (St Lucia or Saint Lucia or Iyonala or Hewanorra).ti,ab. (339)

- 194.

- “Saint Vincent and the Grenadines”/ (52)

- 195.

- (Saint Vincent or St Vincent or Grenadines).ti,ab. (603)

- 196.

- Suriname/ (927)

- 197.

- (Suriname or Dutch Guiana).ti,ab. (572)

- 198.

- Venezuela/ (4896)

- 199.

- Venezuela.ti,ab. (5227)

- 200.

- Djibouti/ (226)

- 201.

- (Djibouti or French Somaliland).ti,ab. (384)

- 202.

- Egypt/ (14699)

- 203.

- Egypt.ti,ab. (13915)

- 204.

- Morocco/ (5673)

- 205.

- Morocco.ti,ab. (5460)

- 206.

- Tunisia/ (8275)

- 207.

- Tunisia.mp. (10358)

- 208.

- (Gaza or West Bank or Palestine).ti,ab. (2434)

- 209.

- Algeria/ (3040)

- 210.

- Algeria.ti,ab. (3189)

- 211.

- Iran/ (26728)

- 212.

- (Iran or Persia).ti,ab. (37869)

- 213.

- Iraq/ (4619)

- 214.

- (Iraq or Mesopotamia).ti,ab. (6991)

- 215.

- Jordan/ (4207)

- 216.

- Jordan.ti,ab. (6109)

- 217.

- Lebanon/ (4260)

- 218.

- (Lebanon or Lebanese Republic).ti,ab. (4462)

- 219.

- Libya/ (1120)

- 220.

- Libya.ti,ab. (1250)

- 221.

- Syria/ (1810)

- 222.

- (Syria or Syrian Arab Republic).ti,ab. (1994)

- 223.

- Yemen/ (1381)

- 224.

- Yemen.ti,ab. (1814)

- 225.

- Afghanistan/ (3197)

- 226.

- Afghanistan.ti,ab. (5834)

- 227.

- Nepal/ (8128)

- 228.

- Nepal.ti,ab. (9629)

- 229.

- Bangladesh/ (10942)

- 230.

- Bangladesh.ti,ab. (13312)

- 231.

- Bhutan/ (458)

- 232.

- Bhutan.ti,ab. (731)

- 233.

- exp India/ (102909)

- 234.

- India.ti,ab. (97774)

- 235.

- Pakistan/ (17537)

- 236.

- Pakistan.ti,ab. (17947)

- 237.

- Maldives.ti,ab. (330)

- 238.

- Sri Lanka/ (5993)

- 239.

- (Sri Lanka or Ceylon).ti,ab. (6894)

- 240.

- Angola/ (997)

- 241.

- Angola.ti,ab. (1388)

- 242.

- Cameroon/ (5461)

- 243.

- (Cameroon or Kamerun or Cameroun).ti,ab. (6869)

- 244.

- Cape Verde/ (199)

- 245.

- (Cape Verde or Cabo Verde).ti,ab. (598)

- 246.

- Comoros/ (307)

- 247.

- (Comoros or Glorioso Islands or Mayotte).ti,ab. (554)

- 248.

- Congo/ (1848)

- 249.

- (Congo not ((Democratic Republic adj3 Congo) or congo red or crimean-congo)).ti,ab. (2549)

- 250.

- Cote d’Ivoire/ (3114)

- 251.

- (Cote d’Ivoire or Cote dIvoire or Ivory Coast).ti,ab. (3806)

- 252.

- Eswatini/ (579)

- 253.

- (eSwatini or Swaziland).ti,ab. (912)

- 254.

- Ghana/ (8167)

- 255.

- (Ghana or Gold Coast).ti,ab. (10613)

- 256.

- Kenya/ (15935)

- 257.

- (Kenya or East Africa Protectorate).ti,ab. (17819)

- 258.

- Lesotho/ (420)

- 259.

- (Lesotho or Basutoland).ti,ab. (704)

- 260.

- Mauritania/ (441)

- 261.

- Mauritania.ti,ab. (617)

- 262.

- Nigeria/ (28351)

- 263.

- Nigeria.ti,ab. (28272)

- 264.

- (Sao Tome adj2 Principe).ti,ab. (151)

- 265.

- Senegal/ (5694)

- 266.

- Senegal.ti,ab. (5639)

- 267.

- Sudan/ (4684)

- 268.

- (Sudan not South Sudan).ti,ab. (7349)

- 269.

- Zambia/ (4496)

- 270.

- (Zambia or Northern Rhodesia).ti,ab. (5215)

- 271.

- Zimbabwe/ (5793)

- 272.

- (Zimbabwe or Southern Rhodesia).ti,ab. (5620)

- 273.

- Botswana/ (1786)

- 274.

- (Botswana or Bechuanaland or Kalahari).ti,ab. (2549)

- 275.

- Equatorial Guinea/ (265)

- 276.

- (Equatorial Guinea or Spanish Guinea).ti,ab. (424)

- 277.

- Gabon/ (1449)

- 278.

- (Gabon or Gabonese Republic).ti,ab. (1722)

- 279.

- Mauritius/ (562)

- 280.

- (Mauritius or Agalega Islands).ti,ab. (967)

- 281.

- Namibia/ (1074)

- 282.

- (Namibia or German South West Africa).ti,ab. (1507)

- 283.

- South Africa/ (41839)

- 284.

- (South Africa or Cape Colony or British Bechuanaland or Boer Republics or Zululand or Transvaal or Natalia Republic or Orange Free State).ti,ab. (33743)

- 285.

- Benin/ (1539)

- 286.

- (Benin or Dahomey).ti,ab. (3401)

- 287.

- Burkina Faso/ (3219)

- 288.

- (Burkina Faso or Burkina Fasso or Upper Volta).ti,ab. (4184)

- 289.

- Burundi/ (634)

- 290.

- (Burundi or Ruanda-Urundi).ti,ab. (884)

- 291.

- Central African Republic/ (778)

- 292.

- (Central African Republic or Ubangi-Shari).ti,ab. (1014)

- 293.

- Chad/ (718)

- 294.

- Chad.ti,ab. (1153)

- 295.

- “Democratic Republic of the Congo”/ (4186)

- 296.

- (((Democratic Republic or DR) adj2 Congo) or Congo-Kinshasa or Belgian Congo or Zaire or Congo Free State).ti,ab. (4465)

- 297.

- Eritrea/ (345)

- 298.

- Eritrea.ti,ab. (536)

- 299.

- Ethiopia/ (12687)

- 300.

- (Ethiopia or Abyssinia).ti,ab. (15414)

- 301.

- Gambia/ (2407)

- 302.

- Gambia.ti,ab. (2290)

- 303.

- Guinea/ (1036)

- 304.

- (Guinea not (New Guinea or Guinea Pig* or Guinea Fowl or Guinea-Bissau or Portuguese Guinea or Equatorial Guinea)).ti,ab. (2608)

- 305.

- Guinea-Bissau/ (925)

- 306.

- (Guinea-Bissau or Portuguese Guinea).ti,ab. (1022)

- 307.

- Liberia/ (1204)

- 308.

- Liberia.ti,ab. (1541)

- 309.

- Madagascar/ (3421)

- 310.

- (Madagascar or Malagasy Republic).ti,ab. (4712)

- 311.

- Malawi/ (5263)

- 312.

- (Malawi or Nyasaland).ti,ab. (6875)

- 313.

- Mali/ (2331)

- 314.

- Mali.ti,ab. (3471)

- 315.

- Mozambique/ (2393)

- 316.

- (Mozambique or Mocambique or Portuguese East Africa).ti,ab. (3567)

- 317.

- Niger/ (1186)

- 318.

- (Niger not (Aspergillus or Peptococcus or Schizothorax or Cruciferae or Gobius or Lasius or Agelastes or Melanosuchus or radish or Parastromateus or Orius or Apergillus or Parastromateus or Stomoxys)).ti,ab. (3410)

- 319.

- Rwanda/ (2407)

- 320.

- (Rwanda or Ruanda).ti,ab. (2980)

- 321.

- Sierra Leone/ (1516)

- 322.

- (Sierra Leone or Salone).ti,ab. (2209)

- 323.

- Somalia/ (1581)

- 324.

- (Somalia or Somaliland).ti,ab. (1476)

- 325.

- South Sudan/ (149)

- 326.

- South Sudan.ti,ab. (528)

- 327.

- Tanzania/ (11298)

- 328.

- (Tanzania or Tanganyika or Zanzibar).ti,ab. (13390)

- 329.

- Togo/ (1133)

- 330.

- (Togo or Togolese Republic or Togoland).ti,ab. (1459)

- 331.

- Uganda/ (12017)

- 332.

- Uganda.ti,ab. (14085)

- 333.

- “africa south of the sahara”/ (11035)

- 334.

- africa, central/ (1278)

- 335.

- africa, eastern/ (4070)

- 336.

- africa, southern/ (2373)

- 337.

- africa, western/ (5817)

- 338.

- (“Africa South of the Sahara” or sub-Saharan Africa or subSaharan Africa).ti,ab. (21003)

- 339.

- Central Africa.ti,ab. (3108)

- 340.

- Eastern Africa.ti,ab. (975)

- 341.

- Southern Africa.ti,ab. (4279)

- 342.

- Western Africa.ti,ab. (831)

- 343.

- or/48-342 (1488989)

- 344.

- 39 and 47 and 343 (16244)

- 345.

- limit 344 to yr = “2016 -Current” (2845)

- 346.

- limit 345 to (english or portuguese) (2792)

Appendix B

Appendix C

| Name (Main Reference) | Aim | Intervention Activities (FP = Family Planning; GBV = Gender-Based Violence; SRH = Sexual and Reproductive Health; SRHR = Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights; RH = Reproductive Health; STI = Sexually Transmitted Infection; yo = Year Olds) | Population and Study Design (cRCT = cluster Randomised Controlled Trial; nRCT = non-Randomised Controlled Trial; RCT = Randomised Controlled Trial) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Punjab Female School Stipend Program (Punjab FSSP) [28] Linked references: [48] | To promote participation in public education for girls in middle school | Intervention arm: conditional cash transfer—conditional on 80% attendance at school Control arm: no cash transfer | Girls only Enrolled in grades 6–8 in public schools Pakistan Natural experiment; historical control |

| Bangladeshi Association for Life Skills, Income and Knowledge for Adolescents (BALIKA) [25] Linked references: [49,50,51,52] | To delay child marriage | All intervention arms: - Safe spaces—weekly meetings with mentor; computer and life skills - Community discussions around the importance of girls’ education and developing their skills, the risk of marrying girls early and other SRH and gender rights issues. Activities included meetings for parents/guardians, local support groups formed with community representatives, advocacy meetings, local events, district workshops Plus: Arm 1: educational tutoring (maths and English if in-school; computing or financial training if out-of-school) Arm 2: gender rights awareness training (life skills training on gender rights, negotiation, critical thinking and decision making) Arm 3: livelihood interventions (training in computers, entrepreneurship, mobile phone servicing, basic first aid) Control arm: no intervention | Girls and parents and community 12–18 yo in and out of school Bangladesh cRCT |

| Mexican school legislation [53] No linked references | To increase schooling | Intervention: legislation extending compulsory schooling from 6th to 9th grade; building of schools Control: women not exposed to the reform (15–22 yo) | Boys and girls 6–9th grade (typically 12–14 yo) Mexico Natural experiment |

| Adolescent Girls Empowerment Program (AGEP) [34] Linked references: [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] | To empower adolescent girls by building their social, health and economic assets, allowing them, in turn, to reduce their vulnerabilities and capitalise on opportunities to improve their health, fertility and educational outcomes | Arm 1: safe spaces—weekly mentor-led girls group meetings on SRH, HIV, life skills and financial education; segmented by age and marital status Arm 2: arm 1 + health voucher (to use at facilities for general or SRH health services) Arm 3: arm 2 + provision of adolescent-friendly savings account Control arm: no intervention | Girls only “most vulnerable” unmarried 10–19 yo Zambia cRCT |

| Safe and smart savings Products for vulnerable adolescent girls (Safe & Smart Savings) [21] Linked references: [62] | Not clear but evaluation was “To understand the social, economic, and health effects of girls’ savings and safe spaces” | Intervention arm: - Safe spaces—weekly group meetings with mentor, stratified by age, with savings activities, health education, fun days, parent meetings - Financial education - Individual savings account with incentives to save Control arm: no intervention | Girls only 10–19 yo Kenya and Uganda nRCT |

| Adolescent Girls Initiative-Kenya (AGI-K) [63] Linked references: [64,65,66,67,68,69] | To delay childbearing for adolescent girls | Arm 1 (control): “community conversations” on violence prevention and valuing girls, plus small fund for implementing action plan (structural intervention) Arm 2: arm 1 + conditional cash transfer for school enrolment and attendance and other education support (fees paid direct to school, kits with sanitary towels, underwear and basic school supplies, incentive paid to schools for enrolment) Arm 3: arm 2 + safe spaces, weekly meetings stratified by age and schooling status, with health, life skills and nutrition curriculum Arm 4: arm 3 + financial education, piggy bank (Wajir) or savings account (Kibera), plus small incentive (USD 3 per year) | Girls and community 11–14 yo Kenya, Wajir (rural) and Kibera (urban) RCT (Kibera) and cRCT (Wajir) |

| Zomba Cash Transfer Program (Zomba CT) [70] Linked references: [71,72,73,74] | HIV prevention | Intervention arm: conditional cash transfer for school enrolment and 80%+ attendance OR unconditional cash transfer of varying amounts for household head and individual girl Control arm: no intervention | Girls only 13–22 yo never married Malawi cRCT |

| Empowerment and Livelihood for Adolescents (ELA-Uganda) [75] Linked references: [76,77] | To break the vicious cycle between low participation in skilled jobs and high fertility | Intervention arm: - Life skills training - Vocational training - Safe spaces (“adolescent development clubs”), open five days a week Control arm: no intervention | Girls only 12–20 yo Uganda cRCT |

| Empowerment & Livelihoods for Adolescents (ELA-Sierra Leone) [78] Linked references: [79,80] | Young women’s socioeconomic empowerment | Intervention: - Safe spaces with mentor (“adolescent development clubs”), open 5× per week - Life skills training with SRH education - Vocational training (17+ yo) - Microfinance (18+ yo) Control: no intervention | Girls only 12–25 yo Sierra Leone, high Ebola disruption area and low Ebola disruption area cRCT |

| Red de Protección Social (RPS) [81] Linked references: [82,83] | To address current and future poverty | Intervention: Conditional cash transfer - Part 1 was conditional on preventive healthcare visits for U5s and attendance at health information workshops - Part 2 was conditional on school attendance and enrolment for 7–13 yo who had not yet completed 4th grade - Information sessions for adolescents on reproductive health and contraception; contraceptives available through healthcare providers Control: delayed intervention | Boys and girls, poor households Rural Nicaragua cRCT |

| Ishraq-pilot phase (“enlightenment” or “sunrise”) [40] Linked references: [84,85] | To transform girls’ lives | Intervention: - Trained program promoters (17–25 yo women), who also mentored girls - Established village committees - Safe spaces (3 h per day, 4× per week) with literacy, sports, life skills (SRHR), home and vocational skills - Health ID card - Life skills classes for 13–17 yo boys (especially participants’ brothers), to encourage gender-equitable thinking, 4× per week for six months - Workshops with parents, community leaders, youth centre staff - Parent meetings—to discuss education, reproductive health, female genital cutting Control: no intervention | Girls and boys and parents and community 13–15 yo Girls out of school Egypt nRCT; pre- and post-intervention with control |

| Kishoree Kontha (Adolescent Girl’s Voice) [32] Linked references: [86] | To reduce child marriage, teenage childbearing and to increase education | Arm 1: empowerment program - Safe spaces with peer educators, 2 h, 5–6 times per week for 6 months for curriculum, then ongoing - Education support: literacy, numeracy and oral communication - Social competency: life skills, nutritional and reproductive health knowledge - Half also received financial literacy training and encouragement to generate own income Arm 2: incentive—cooking oil for household every 4 months if girl remained unmarried until legal age of consent (18 yo) Arm 3: arm 1 + arm 2 Control: no intervention | Girls only 10–19 yo, arm 1 15–17 yo and unmarried, arm 2 Bangladesh cRCT |

| Empowerment and Livelihood for Adolescents program (ELA–Tanzania) [22] Linked references: [87] | To improve the human capital of young women | Arm 1: ELA intervention - Safe spaces (adolescent girls clubs) with mentor for recreation and socialising, five days per week with life skills training, as well as livelihood and vocational training - Community meetings with parents and village elders Arm 2: arm 1 + microcredit services for older girls, plus financial literacy training and business planning support Control arm: no intervention | Girls and parents and community 13–17 yo Tanzania cRCT |

| Regai Dzive Shiri [24] Linked references: [88,89,90] | HIV prevention—to change societal norms | Intervention: - Youth program for in- and out-of-school youth - Community-based program for parents and stakeholders to improve RH knowledge, parent–child communication, community support for adolescent RH - Clinic staff training to increase accessibility Control: delayed intervention (to 2007, year of final survey) | Girls and boys and parents and community Age unclear (“youth”) Zimbabwe cRCT |

| Social Cash Transfer Program (SCTP) & Multiple Category Targeted Grant (MCTG) [91] No linked references | SCTP: To reduce poverty and hunger, and improve school enrolment rates MCTG: To reduce extreme poverty and intergenerational transfer of poverty | Intervention, SCTP: unconditional cash transfer, 2 years, Malawi Intervention, MCTG: unconditional cash transfer, 3 years, Zambia Control: no intervention | Girls and boys 14–21 yo (for evaluation; programmes were for broader group of households) Most vulnerable households Malawi and Zambia cRCT |

| Oportunidades [42] Linked references: [92,93,94,95] | To reduce poverty and develop human capital in poor households via improvements in child nutrition, health and education | Intervention: - Cash transfer conditional on school attendance - Six monthly health check-ups for adolescents and adults - Health promotion talks to household head and students of middle–high education level - Nutritional supplementation Control: not exposed to intervention | Girls only 15–19 yo (for evaluation; programme available for boys and households with other ages) Mexico Natural experiment—survey of exposure to programme |

| Ghanaian School scholarship programme [39] Linked references: [96] | To increase secondary school education | Intervention: four-year scholarship program for senior high school tuition fees, paid directly to school Control: no intervention | Boys and girls 13–25 yo Ghana RCT |

| Kenyan School subsidies and teacher training [35] No linked references | Not explicit but assumed to encourage primary school education and HIV prevention | Arm 1: provision of free school uniform Arm 2: teaching training on HIV/AIDS prevention curriculum for upper primary school (focused on abstinence until marriage, plus discussion of condoms) (not structural) Arm 3: 1 and 2 Control arm: no intervention | Boys and girls Enrolled in 6th grade Kenya cRCT |

| Shaping the Health of Adolescents in Zimbabwe (SHAZ!) [26] Linked references: [97,98] | HIV prevention | Intervention: - Control arm activities - Financial literacy education - Vocational training + micro grant on completion - Integrated social support (guidance counselling plus mentors) Control: - RH health screening + provision of free FP every 6 months (for intervention and control groups) - Life skills education + home-based care training | Girls only 16–19 yo out-of-school orphans (lost at least 1 parent) Zimbabwe RCT |

| Berhane Hewan (“Light for Eve”) [31] Linked references: [99,100] | To reduce early marriage and support married adolescent girls | Intervention: - Parents of unmarried pledged that they would not be married during the 2 year programme - Goat incentive for parents, if remain unmarried and attend 80%+ of safe space meetings - Community conversations - Community water wells constructed In-school girls: - Provision of school materials, mentors to track and support attendance and performance and encouragement to remain in school Out-of-school girls: - As above, if wanted to return to school OR - Safe space groups for married (weekly) or unmarried (five times per week) girls with basic literacy and numeracy, livelihoods skills, financial literacy, group savings and loan scheme, referral to health centre for those requesting, with cost of clinic card provided Control: no intervention | Girls and community 10–19 yo Married and unmarried Ethiopia nRCT; pre- and post-intervention with control |

| Kenyan education reform [37] No linked references | To increase education | Intervention: reform of education system—increased primary school by one year in 1985 Control: historical control | Girls and boys (age not stated) Kenya Natural experiment—DHS data from before/after reform |

| Turkish schooling legislation [101] Linked reference: [102] | To increase education level | Intervention: - Change in compulsory schooling law—extended basic educational requirement from 5 to 8 years (free of charge) in 1997 Control: historical control (i.e., those aged 23+ years in 2008) | Boys and girls Turkey Natural experiment—DHS data from before/after |

| Zimbabwean comprehensive school support [36] Linked references: [103,104,105] | HIV prevention | Intervention: - School support: fees, books, uniforms and other supplies - Female teachers trained as helpers (monitor attendance/assist with absenteeism) Control: no intervention | Girls only Grade 6, orphans (at least 1 parent deceased) Zimbabwe cRCT |

| Mabinti Tushike Hatamu! (Girls Lets Be Leaders!) [106] Linked references: [107] | To reduce vulnerability to HIV/AIDS, pregnancy and GBV | Intervention: - Girls’ groups with safe spaces: SRH training; financial and vocational skills; participatory action research; saving money; income generation Control: no intervention | Girls only 10–19 yo, out of school Tanzania nRCT; post-intervention only with control |

| Cash Transfer for Orphans and Vulnerable Children (Kenyan Cash Transfer—OVC) [108] Linked references: [109] | To reduce poverty | Intervention: unconditional cash transfer Control: no intervention | Boys and girls Ultra-poor households with at least one orphan/vulnerable child under 18 yo (at least one deceased parent, or parent/carer who is chronically ill) Kenya nRCT, pre- and post-intervention with control |

| Child Support Grant [110] Linked references: [111,112,113,114] | To improve the quality of life of impoverished children | Intervention: unconditional cash transfer Control: no intervention | Girls and boys Parent/caregiver of 0–18 yo, on low income South Africa Natural experiment |

| Indian employment opportunities intervention [115] No linked references | Not explicit—assumed to increase employment | Intervention: employment opportunities (business process outsourcing recruiting services) Control: no intervention | Girls only India cRCT |

| Development Initiative Supporting Healthy Adolescents (DISHA) [43] Linked references: [116] | To improve SRH outcomes among youth | Intervention: - Established youth groups and youth resource centres (with health education and safe space) - Peer educators - Livelihoods training/groups, some linked to micro savings/credit groups - Mass communication activities - Adult groups - Adult–youth partnership groups - Training health workers on youth friendly health services - Youth depot holders, including married and unmarried (FP counselling and social marketing) Control: no intervention | Boys and girls and parents and community 14–24 yo, married and unmarried India nRCT; pre- and post-intervention; no control reported |

| Young Agent Project [117] No linked references | To keep adolescents in school, out of work, prevent violent and risky behaviours as well as to make them community leaders in their own Favelas (Slums) | Intervention: - Cash transfer conditional on attendance at both school and after school program (recreation, health talks, trips, computing skills, job training, internship) Control: no intervention | Boys and girls 15–17 yo, urban low income Brazil Natural experiment; post-hoc dataset with control |

| Marriage: No Child’s Play” (MNCP) [33] Linked references: [118,119,120,121] | To reduce child marriage | Intervention: - Girls’ groups with safe spaces: life skills, SRHR information, peer support, self-defence training, vocational training, arts and sports - Supporting schools to reduce drop out - Link girls/families to social protection schemes/income-generating opportunities - Financial literacy training - Strengthening child protection systems - Outreach SRHR services - Vouchers for SRHR services - Training service providers - Community conversations - Training officials to enforce laws and implement child marriage ban policies - Advocate for policy change Control: no intervention | Girls and families and communities 14–24 yo Unmarried and married India, Malawi, Mali, Niger cRCT (India and Malawi) nRCT (Mali and Niger) |

| Sawki [30] Linked references: [122,123,124] | To improve adolescent girls’ nutrition before pregnancy; to delay adolescent pregnancy | Arm 1: control group + safe spaces with mentor, weekly meetings - Teach life skills, essential nutrition actions, risks of early marriage and early pregnancy, the importance of education, literacy - Married girls learn more about RH - 50 kg lentils every 6 months conditional on attendance at 80%+ of meetings Arm 2: control group + arm 1 + livelihood training + savings and loan activities Control arm: Sawki development food assistance program (aim to reduce chronic malnutrition among pregnant/lactating women and children under 5 yo, and to increase local availability of and household’s access to nutrition foods) - Caregiver groups and husband schools, both providing information on nutrition and health (including contraception/fertility) - Mass media and other sensitisation on food production and nutrition - Advocacy sessions for women’s groups to obtain property ownership - Practical and technical food production support (vegetables and animals) - Village saving and loan association groups supported | Girls only 10–18 yo Niger nRCT; post-intervention with control |

| Community-embedded reproductive health care for adolescents (CERCA) [125] Linked references: [126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133] | To improve access to, and the use of, SRH services by adolescents | Intervention: - Media, workshops in health centres/community centres (Nicaragua) or schools (Bolivia and Ecuador) and discussion groups with parents/grandparents - Healthcare provider training - Contraceptive supply to health centres - Media campaigns - Information event with officials Bolivia and Ecuador only: - SRH workshops and youth groups in schools Nicaragua only: - Community-level education and door-to-door outreach - Friends of Youth (mentors) Control: no intervention | Boys and girls and parents and community Urban youth Nicaragua, Bolivia, Ecuador cRCT (Nicaragua) nRCT; pre- and post-intervention with control (Bolivia and Ecuador) |

| Universal Primary Education Program (UPE) [38] No linked references | Not explicit—assumed to increase primary education rates | Intervention: national introduction of tuition-free primary education in 1976 Control: women born between 1956 and 1961 (i.e., aged 15–20 when intervention started) | Boys and girls Nigeria Natural experiment |

| Girl Empower [41] No linked references | To reduce sexual abuse among females in early adolescence | Arm 1: Girl Empower - Safe spaces, with mentors, meeting weekly, with life skills curriculum including financial literacy and RH, community action events and graduation ceremonies with community stakeholders - Monthly parents/caregivers discussion group, to gain support from parents for intervention and to support/protect girls in their communities - Monthly cash sum (USD 2) for 8 months to start savings account, plus savings book and cash box - Training for quality health and psychosocial service providers for survivors of GBV Arm 2: Girl Empower + - Arm 1 - Caregivers receive conditional cash transfer for each session attended by girl Control arm: no intervention | Girls only 13–14 yo, rural Liberia cRCT |

| Promoting Change in Reproductive Behaviour of Adolescents—phase III (PRACHAR III) [134] Linked references: [135,136,137,138,139] | To delay the age at first birth and space subsequent births by at least 3 years | Arm 1: small-group education on SRH and life skills for 15–19 yo unmarried boys and girls, separately (not structural) Arm 2: - Arm 1 - Small-group education on RH for girls, 12–14 yo - Home visits to young married women for RH/FP counselling and referrals to FP services - Small group discussion and dialogue among young married men and young married women (separately) on RH and contraception, referrals to health services - Training of providers in youth friendly health services - Training programmes and sensitisation sessions with various groups: parents, husbands, community, healthcare providers Control arm: no intervention | Boys and girls and family and community 12–24 yo India nRCT; post-intervention with control |

| Girl Power-Malawi [29] Linked references: [140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147] | To impact HIV and SRH health service utilisation | Arm 1 (control): standard care clinic: HIV testing, FP, STI syndromic management and condoms Arm 2: youth-friendly clinic including wider opening times, provider training, young peer educators (not structural) Arm 3: arm 2 + monthly small group sessions on HIV and SRH information, healthy and unhealthy romantic relationships, financial literacy, skills, e.g., problem solving and communication, for one year Arm 4: arm 3 + monthly cash transfer (to participant) conditional on attending each small group session | Girls only 15–24 yo Malawi nRCT; pre- and post-intervention with control |

| First-Time Parents Project [23] Linked references: [148] | To empower married young women and improve their sexual and reproductive health | Intervention: - Groups for married girls, meeting 2–3 h per month, topics such as legal literacy, vocational skills, health, gender, relationships, and worked on development projects. One group set up a group savings account - Home visits by outreach workers to young women and to their husbands, providing information on sex, communication, respect, joint decision making and RH topics including family planning - Community activities, e.g., health fairs - Opportunistic interactions with mothers-in-law and senior female family members about sexual health, contraception, antenatal, delivery and postpartum care, husbands’ roles in this period - Training health service providers on needs of young married women - Training traditional birth attendants and provision of safe delivery kits - Counselling in clinics - Provision of condoms and pill through peers and clinics - Strengthened antenatal services through outreach, financial assistance when needed for antenatal care, provided postpartum home visits Control: no intervention | Married young women and their husbands, families and community India nRCT; pre- and post-intervention with control |

| Ishraq “sunrise”—scale-up phase [27] Linked references: [149,150] | To address the specific needs of adolescent girls in a holistic manner | Intervention: - Safe spaces with mentors, 3 h per day, 4× per week, with literacy, basic maths, financial literacy, life skills, sports - Savings accounts, with initial deposit (USD 15) - Orientation of parents regarding savings account - Snacks and monthly food ration conditional on regular attendance - Graduation ceremony with community - Established village committee—to inform community about program, girls’ education and gender equity - Life skills classes for boys 13–17 yo to sensitise on gender quality, civil and human rights, self-responsibility - Tutoring for girls in Arabic, English and other school subjects - Home visits to convince parents of importance of girl’s continuing education - Community mobilisation, e.g., community seminars Control: no intervention | Girls and boys and parents and community 11–15 yo out-of-school girls 13–17 yo boys Egypt nRCT; pre- and post-intervention (compared participants with non-participants) |

| Programa de Educacion, Salud y Alimentacion (Progresa) Programa de Asignación Familiar—family allowance program (PRAF II) [151] Linked references: [95,152] | Progresa: To reduce poverty and invest in human capital PRAF II: To increase human capital accumulation, through education and health, to decrease chronic poverty | Intervention (Progresa): - Cash transfer conditional on school attendance, visits to public health clinics and attendance at educational workshops on health and nutrition Intervention (PRAF II): - Two cash transfers, one conditional on school enrolment and attendance for 6–12 yo, another conditional on regular health checks for pregnant women and under 3 yo Control: no intervention | Chronically poor, rural households Mexico (Progresa) Honduras (PRAF II) cRCT |

| Gender Roles, Equality and Transformations Project (GREAT) [153] Linked references: [154,155,156,157,158] | To reduce gender-based violence and improve sexual and reproductive health outcomes | Intervention: - Community action cycle—community action groups - Radio drama aimed at creating discussion around gender equality, GBV and SRH - Village health team member training - Toolkit for use in existing groups, tailored to married/parenting 15–19 yo, or unmarried, nulliparous 15–19 yo, or 10–14 yo in school Control: no intervention | Boys and girls and community 10–19 yo: NM/NP (newly married/newly parenting 15–19 yo), OAs (older adolescents—unmarried, nulliparous 15–19 yo) - 10–14 yo in school Uganda nRCT; pre- and post-intervention with control |

References

- Chandra-Mouli, V.; Ferguson, B.J.; Plesons, M.; Paul, M.; Chalasani, S.; Amin, A.; Pallitto, C.; Sommers, M.; Avila, R.; Biaukula, K.V.E.; et al. The Political, Research, Programmatic, and Social Responses to Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in the 25 Years Since the International Conference on Population and Development. J. Adolesc. Health 2019, 65, S16–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/1 (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Li, Z.; Patton, G.; Sabet, F.; Zhou, Z.; Subramanian, S.V.; Lu, C. Contraceptive Use in Adolescent Girls and Adult Women in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e1921437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oringanje, C.; Meremikwu, M.M.; Eko, H.; Esu, E.; Meremikwu, A.; Ehiri, J.E. Interventions for preventing unintended pregnancies among adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2, CD005215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason-Jones, A.J.; Sinclair, D.; Mathews, C.; Kagee, A.; Hillman, A.; Lombard, C. School-based interventions for preventing HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and pregnancy in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 11, CD006417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denno, D.M.; Hoopes, A.J.; Chandra-Mouli, V. Effective strategies to provide adolescent sexual and reproductive health services and to increase demand and community support. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015, 56, S22–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phiri, M.; King, R.; Newell, J.N. Behaviour change techniques and contraceptive use in low and middle income countries: A review. Reprod. Health. 2015, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mwaikambo, L.; Speizer, I.S.; Schurmann, A.; Morgan, G.; Fikree, F. What Works in Family Planning Interventions: A Systematic Review. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2011, 42, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McQueston, K.; Silverman, R.; Glassman, A. The efficacy of interventions to reduce adolescent childbearing in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Stud. Fam. Plann. 2013, 44, 369–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaid, L.; Dumont, A.; Chaillet, N.; Zertal, A.; De Brouwere, V.; Hounton, S.; Ridde, V. Effectiveness of demand generation interventions on use of modern contraceptives in low- and middle-income countries. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2016, 21, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanemyr, J.; Amin, A.; Robles, O.J.; Greene, M.E. Creating an Enabling Environment for Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health: A Framework and Promising Approaches. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, S7–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumartojo, E.; Doll, L.; Holtgrave, D.; Gayle, H.; Merson, M. Enriching the mix: Incorporating structural factors into HIV prevention. AIDS 2000, 14, S1–S2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutumba, M.; Wekesa, E.; Stephenson, R. Community influences on modern contraceptive use among young women in low and middle-income countries: A cross-sectional multi-country analysis. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaymaker, E.; Scott, R.H.; Palmer, M.J.; Palla, L.; Marston, M.; Gonsalves, L.; Say, L.; Wellings, K. Trends in sexual activity and demand for and use of modern contraceptive methods in 74 countries: A retrospective analysis of nationally representative surveys. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e567–e579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K.; Heard, A.; Diaz, N. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health: Scoping the Impact of Programming in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; Scoping Paper 5; International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3i3): New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Glinski, A.; Sexton, M.; Petroni, S. Understanding the Adolescent Family Planning Evidence Base; International Center for Research on Women (ICRW): Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, K.; Jarvis-Thiébault, J.; Pfeifer, N.; Engelbert, M.; Perng, J.; Yoon, S.; Heard, A. Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health: An Evidence Gap Map; International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie): New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Deitch, J.; Stark, L. Adolescent demand for contraception and family planning services in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Glob. Public Health 2019, 14, 1316–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Working for a Brighter, Healthier Future: How WHO Improves Health and Promotes Well-being for the World’s Adolescents. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240041363 (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- The World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups. 2020. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Austrian, K.; Muthengi, E. Safe and Smart Savings Products for Vulnerable Adolescent Girls in Kenya and Uganda: Evaluation Report; Population Council: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Buehren, N.; Goldstein, M.P.; Gulesci, S.; Sulaiman, M.; Yam, V. Evaluation of an Adolescent Development Program for Girls in Tanzania (No. WPS7961; pp. 1–25). The World Bank. 2017. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/245071486474542369/Evaluation-of-an-adolescent-development-program-for-girls-in-Tanzania (accessed on 11 February 2021).

- Santhya, K.G.; Haberland, N.; Das, A.; Lakhani, A.; Ram, F.; Sinha, R.K.; Ram, U.; Mohanty, S.K. Empowering Married Young Women and Improving Their Sexual and Reproductive Health: Effects of the First-Time Parents Project; Population Council: New Delhi, India, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, F.M.; Pascoe, S.J.; Langhaug, L.F.; Mavhu, W.; Chidiya, S.; Jaffar, S.; Mbizvo, M.T.; Stephenson, J.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Power, R.M.; et al. The Regai Dzive Shiri project: Results of a randomized trial of an HIV prevention intervention for youth. AIDS 2010, 24, 2541–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, S.; Ahmed, J.; Sah, J.; Hossain, M.; Haque, E. Delaying Child Marriage through Community-Based Skills-Development Programs for Girls. Results from a Randomized Controlled Study in Rural Bangladesh; Population Council: New York, NY, USA; Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar, M.S.; Kang Dufour, M.S.; Lambdin, B.; Mudekunye-Mahaka, I.; Nhamo, D.; Padian, N.S. The SHAZ! project: Results from a pilot randomized trial of a structural intervention to prevent HIV among adolescent women in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selim, M.; Abdel-Tawab, N.; Elsayed, K.; el Badawy, A.; el Kalaawy, H. The Ishraq Program for Out-of-School Girls: From Pilot to Scale-Up; Population Council: Cairo, Egypt, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, A.; Baez, J.E.; Del Carpio, X.V. Does Cash for School influence Young Women’s Behavior in the Longer Term? Evidence from Pakistan; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, N.E.; Bhushan, N.L.; Vansia, D.; Phanga, T.; Maseko, B.; Nthani, T.; Libale, C.; Bamuya, C.; Kamtsendero, L.; Kachigamba, A.; et al. Comparing Youth-Friendly Health Services to the Standard of Care through “Girl Power-Malawi”: A Quasi-Experimental Cohort Study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. JAIDS 2018, 79, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercycorps. Improving Child and Maternal Health: Why Adolescent Girl Programming Matters. Post Intervention Evidence From Niger. 2015. Available online: https://www.mercycorps.org/sites/default/files/2019-11/mercy_corps_niger_rising.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Erulkar, A.; Eunice, M. Evaluation of Berhane Hewan: A Program to Delay Child Marriage in Rural Ethiopia. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2009, 35, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, N.; Field, E.; Glennerster, R.; Nazneen, S.; Pimkina, S.; Sen, I. Power vs Money: Alternative Approaches to Reducing Child Marriage in Bangladesh, a Randomized Control Trial. Res. Pap. 2018; Unpublished Manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Melnikas, A.; Saul, G.; Chau, M.; Pandey, N.; Mkandawire, J.; Gueye, M.; Diarra, A.; Amin, S. More Than Brides Alliance: Endline Evaluation Report; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Behrman, J.; Digitale, J.; Hachonda, N.; Bweupe, M.; Hewett, P. The impact of the Adolescent Girls Empowerment Program (AGEP) on short and long term social, economic, education and fertility outcomes: A cluster randomized controlled trial in Zambia. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E.; Dupas, P.; Kremer, M. Education, HIV, and early fertility: Experimental evidence from Kenya. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 2757–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallfors, D.; Cho, H.; Rusakaniko, S.; Iritani, B.; Mapfumo, J.; Halpern, C. Supporting adolescent orphan girls to stay in school as HIV risk prevention: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in Zimbabwe. Am. J. Public Health 2011, 101, 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferré, C. Age at First Child: Does Education Delay Fertility Timing? The Case of Kenya; Policy Research Working Paper Series; SSRN: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Osili, U.O.; Long, B.T. Does female schooling reduce fertility? Evidence from Nigeria. J. Dev. Econ. 2008, 87, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflo, E.; Dupas, P.; Kremer, M. Estimating the Benefit to Secondary School in Africa: Experimental Evidence from Ghana; Working paper F-2020-GHA-1; International Growth Centre: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, M.; Assaad, R.; Ibrahim, B.; Salem, A.; Salem, R.; Zibani, N. Providing New Opportunities to Adolescent Girls in Socially Conservative Settings: The Ishraq Program in Rural Upper Egypt—Full Report; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ozler, B.; Hallman, K.; Guimond, M.-F.; Kelvin, E.; Rogers, M.; Karnley, E. Girl Empower—A gender transformative mentoring and cash transfer intervention to promote adolescent wellbeing: Impact findings from a cluster-randomized controlled trial in Liberia. SSM Popul. Health 2020, 10, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darney, B.G.; Weaver, M.R.; Sosa-Rubi, S.G.; Walker, D.; Servan-Mori, E.; Prager, S.; Gakidou, E. The Oportunidades conditional cash transfer program: Effects on pregnancy and contraceptive use among young rural women in Mexico. Int. Perspect. Sex. Reprod. Health 2013, 39, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanesathasan, A. Catalyzing Change: Improving Youth Sexual and Reproductive Health through DISHA, an Integrated Program in India; International Center for Research on Women (ICRW): Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk, L.B.; Ortayli, N. Interventions to improve adolescents’ contraceptive behaviors in low- and middle-income countries: A review of the evidence base. Contraception 2014, 90, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhoma, D.; Lin, C.-P.; Katengeza, H.; Soko, C.; Estinfort, W.; Want, Y.-C.; Juan, S.-H.; Jian, W.-S.; Iqubal, U. Girls’ Empowerment and Adolescent Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.K.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Ashby, C.; Quandt, M.; Halsey, E.; Nagar, A.; Greene, M.E. Characteristics of successful programmes targeting gender inequality and restrictive gender norms for the health and wellbeing of children, adolescents, and young adults: A systematic review. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e225–e236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Chandra-Mouli, V.; Jain, K.; Behera, J.; Mishra, S.K.; Mehra, S. Community based reproductive health interventions for young married couples in resource-constrained settings: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Independent Evaluation Group. Do Conditional Cash Transfers Lead to Medium-Term Impacts? Evidence from a Female School Stipend Program in Pakistan; Population Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, S.; Ainul, S.; Akter, F.; Alam, M.M.; Hossain, I.; Ahmed, J.; Rob, U. From Evidence to Action: Results from the 2013 Baseline Survey for the BALIKA Project; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, S.; Saha, J.S.; Ahmed, J.A. Skills-Building Programs to Reduce Child Marriage in Bangladesh: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Adolesc. Health 2018, 63, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, J.; Amin, S. Exploring Impact of BALIKA program on Adolescent Reproductive Health Knowledge, Perceptions about Gender Violence, and Behavior among Girls in Rural Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 2016 Population Association of America (PAA) Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 30 April–2 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- International Sexuality and HIV Curriculum Working Group. It’s All One Curriculum: Volume 1: Guidelines for a Unified Approach to Sexuality, Gender, HIV and Human Rights Education; Haberland, H., Rogow, D., Eds.; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Andalón, M.; Williams, J.; Grossman, M. Empowering Women: The Effect of Schooling on Young Women’s Knowledge and Use of Contraception; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Duby, Z.; Hewett, P.C. “When He Asks for Sex, You Will Never Refuse”: Transactional Sex and Adolescent Pregnancy in Zambia. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2019, 50, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Hewett, P.C.; Hachonda, N.J.; Behrman, J.R. Adolescent Girls Empowerment Programme: Endline Technical Report; Population Council: Lusaka, Zambia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, S.; Haberland, N.; McCarthy, K.J.; Weber, A.M.; Darmstadt, G.L.; Ngo, T.D. The influence of schooling on the stability and mutability of gender attitudes: Findings from a longitudinal study of adolescent girls in Zambia. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 66, S25–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duby, Z.; Zulu, C.N.; Austrian, K. Adolescent Girls Empowerment Programme in Zambia: Qualitative Evaluation Report; Population Council: Lusaka, Zambia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hewett, P.C.; Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Behrman, J.R.; Bozzani, F.; Jackson-Hachonda, N.A. Cluster randomized evaluation of Adolescent Girls Empowerment Programme (AGEP): Study protocol. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mott MacDonald Evaluation Team. Adolescent Girls Empowerment Programme, Zambia. End Term Evaluation Report. Volume I: Main Report; Mott MacDonald: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Psaki, S.R.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Saha, J.; Mensch, B.S.; Amin, S. The Effects of Adolescent Childbearing on Literacy and Numeracy in Bangladesh, Malawi, and Zambia. Demography 2019, 56, 1899–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.J.; Wyka, K.; Romero, D.; Austrian, K.; Jones, H.E. The development of adolescent agency and implications for reproductive choice among girls in Zambia. SSM Popul. Health 2022, 17, 101011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitzhak, K.A. Reproductive Health Effects of a Safe Spaces, Financial Education, and Savings Program for Vulnerable Adolescent Girls in Uganda; Ben-Gurion University of the Negev: Beersheba, Israel, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Kangwana, B.; Maddox, N.; Wado, Y.; Abuya, B.; Shah, V.; Maluccio, J. Adolescent Girls Initiative–Kenya: Endline Evaluation Report; Population Council: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Austrian, K.; Muthengi, E.; Mumah, J.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Kabiru, C.W.; Abuya, B.; Maluccio, J.A. The Adolescent Girls Initiative-Kenya (AGI-K): Study protocol. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Mumah, J.; Kangwana, B.; Wado, Y.; Abuya, B.; Shah, V.; Maluccio, J. Adolescent Girls Initiative–Kenya. Midline Results Report; Population Council: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Kangawana, B.; Wado, Y.D.; Abuya, B.; Maluccio, J. Impacts of two-year multisectoral cash plus programs on young adolescent girls’ education, health and economic outcomes: Adolescent Girls Initiative-Kenya (AGI-K) randomized trial. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austrian, K.; Muthengi, E.; Riley, T.; Mumah, J.; Kabiru, C.W.; Abuya, B.A.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Maluccio, J. Adolescent Girls Initiative–Kenya. Baseline Report; Population Council: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Kangwana, B.; Maddox, N.; Diaw, M.; Wado, Y.D.; Abuya, B.; Muluve, E.; Mbushi, F.; Mohammed, H.; et al. Impacts of Multisectoral Cash Plus Programs on Marriage and Fertility After 4 Years in Pastoralist Kenya: A Randomized Trial. J. Adolesc. Health 2022, 70, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangwana, B.; Austrian, K.; Soler-Hampejsek, E.; Maddox, N.; Sapire, R.J.; Wado, Y.D.; Abuya, B.; Muluve, E.; Mbushi, F.; Koech, J.; et al. Impacts of multisectoral cash plus programs after four years in an urban informal settlement: Adolescent Girls Initiative-Kenya (AGIK) randomized trial. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0262858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, S.M.; McIntosh, C.; Özler, B. When the Money Runs Out: Do Cash Transfers Have Sustained Effects on Human Capital Accumulation? Policy Research Working Paper No. 7901; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25705 (accessed on 24 November 2020).

- Baird, S.; Chirwa, E.; de Hoop, J.; Özler, B. Girl Power: Cash Transfers and Adolescent Welfare. Evidence from a cluster-randomized experiment in Malawi. In African Successes: Human Capital; Edwards, S., Johnson, S., Weil, D.N., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, S.; Chirwa, E.; McIntosh, C.; Ozler, B. The short-term impacts of a schooling conditional cash transfer program on the sexual behavior of young women. Health Econ. 2010, 19, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, S.; McIntosh, C.; Özler, B. Cash or condition? Evidence from a cash transfer experiment. Q. J. Econ. 2011, 126, 1709–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, S.J.; Garfein, R.S.; McIntosh, C.T.; Ozler, B. Effect of a cash transfer programme for schooling on prevalence of HIV and herpes simplex type 2 in Malawi: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2012, 379, 1320–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, O.; Buehren, N.; Burgess, R.; Goldstein, M.; Gulesci, S.; Rasul, I.; Sulaiman, M. Women’s Empowerment in Action: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial in Africa. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2020, 12, 210–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, O.; Buehren, N.; Burgess, R.; Goldstein, M.; Gulesci, S.; Rasul, I.; Sulaiman, M. Empowering Adolescent Girls: Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial in Uganda; London School of Economics: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera, O.; Goldstein, M.; Rasul, I.; Burgess, R.; Gulesci, S.; Sulaiman, M. Intentions to Participate in Adolescent Training Programs: Evidence From Uganda. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2010, 8, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandiera, O.; Buehren, N.; Goldstein, M.; Rasul, I.; Smurra, A. The Economic Lives of Young Women in the Time of Ebola: Lessons from an Empowerment Program; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera, O.; Buehren, N.; Goldstein, M.; Rasul, I.; Smurra, A. Empowering Adolescent Girls in a Crisis Context: Lessons from Sierra Leone in the Time of Ebola; Gender Innovation Lab Policy Brief; No. 34; Population Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bandiera, O.; Buehren, N.; Goldstein, M.; Rasul, I.; Smurra, A. Do School Closures during an Epidemic have Persistent Effects? Evidence from Sierra Leone in the Time of Ebola; a J-PAL Working Paper. 2020. Available online: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/research-paper/working-paper_720_School-Closures-During-Epidemic_Sierra-Leone_July2020.pdf (accessed on 8 February 2021).

- Barham, T.; Macours, K.; Maluccio, J.A. Experimental Evidence of Exposure to a Conditional Cash Transfer During Early Teenage Years: Young Women’s Fertility and Labor Market Outcomes. 2018. Available online: https://www.povertyactionlab.org/sites/default/files/research-paper/Experimental-Evidence-of-Exposure-to-a-CCT-During%20Early-Teenage-Years_BMM_August2018.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Gitter, S.R.; Barham, B.L. Women’s Power, Conditional Cash Transfers, and Schooling in Nicaragua. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2008, 22, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thomas, R. Conditional Cash Transfers to Improve Education and Health: An Ex Ante Evaluation of Red De Protección Social, Nicaragua. Health Econ. 2012, 21, 1136–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, M.; Assaad, R.; Ibrahim, B.L.; Salem, A.; Salem, R.; Zibani, N. Providing New Opportunities to Adolescent Girls in Socially Conservative Settings: The Ishraq Program in Rural Upper Egypt; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ringler, K. A Review of the Ishraq Program’s Quasi-Experimental Impact Evaluation; Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann, N.; Field, E.; Glennerster, R.; Nazneen, S.; Pimkina, S.; Sen, I. The Effect of Conditional Incentives and a Girls’ Empowerment Curriculum on Adolescent Marriage, Childbearing and Education in Rural Bangladesh: A Community Clustered Randomized Controlled Trial. 2016. Available online: https://www.poverty-action.org/publication/effect-conditional-incentives-and-girls%E2%80%99-empowerment-curriculum-adolescent-marriage (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Buehren, N.; Goldstein, M.; Gulesci, S.; Sulaiman, M.; Yam, V. Evaluation of Layering Microfinance on an Adolescent Development Program for Girls in Tanzania; Brac Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD): Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, F.M.; Langhaug, L.F.; Mashungupa, G.P.; Nyamurera, T.; Hargrove, J.; Jaffar, S.; Peeling, R.W.; Brown, D.W.G.; Power, R.; Johnson, A.M.; et al. School based HIV prevention in Zimbabwe: Feasibility and acceptability of evaluation trials using biological outcomes. AIDS 2002, 16, 1673–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, F.M.P.S.J.S.; Langhaug, L.F.; Dirawo, J.; Chidiya, S.; Jaffar, S.; Mbizvo, M.; Stephenson, J.M.; Johnson, A.M.; Power, R.M.; Woelk, G.; et al. The Regai Dzive Shiri Project: A cluster randomised controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of a multi-component community-based HIV prevention intervention for rural youth in Zimbabwe—Study design and baseline results. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2008, 13, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhaug, L.F.; Cheung, Y.B.; Pascoe, S.J.S.; Chirawu, P.; Woelk, G.; Hayes, R.J.; Cowan, F.M. How you ask really matters: Randomised comparison of four sexual behaviour questionnaire delivery modes in Zimbabwean youth. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2011, 87, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dake, F.; Natali, L.; Angeles, G.; Hoop, J.d.; Handa, S.; Peterman, A. Cash transfers, early marriage, and fertility in Malawi and Zambia. Stud. Fam. Plan. 2018, 49, 295–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galárraga, O.; Gertler, P.J. Conditional Cash & Adolescent Risk Behaviors: Evidence from Urban Mexico; Policy Research Working Paper; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gulemetova, M. Evaluating the Impact of Conditional Cash Transfer Programs on Adolescent Decisions about Marriage and Feritlity: The Case of Oportunidades; University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lamadrid-Figueroa, H.; Angeles, G.; Mroz, T.; Urquieta-Salomón, J.; Hermández-Prado, B.; Cruz-Valdez, A.; Téllez-Rojo, M.M. Impact of Oportunidades on Contraceptive Methods Use in Adolescent and Young Adult Women Living in Rural Areas, 1997–2000; Working Paper Series; University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carolina Population Center, MEASURE Evaluation: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Skoufias, E. PROGRESA and Its Impacts on the Welfare of Rural Households in Mexico; Research Report Abstract 139; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Duflo, E.; Dupas, P.; Kremer, M. The Impact of Free Secondary Education: Experimental Evidence from Ghana. 2017. Available online: https://docs.opendeved.net/lib/AE6GNNGX (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Dunbar, M.S.; Maternowska, M.C.; Kang, M.S.J.; Laver, S.M.; Mudekunye-Mahaka, I.; Padian, N.S. Findings from SHAZ!: A feasibility study of a microcredit and life-skills HIV prevention intervention to reduce risk among adolescent female orphans in Zimbabwe. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2010, 38, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.; Dunbar, M.; Laver, S.; Padian, N. Maternal versus paternal orphans and HIV/STI risk among adolescent girls in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care 2008, 20, 214–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karei, E.M.; Erulkar, A.S. Building Programs to Address Child Marriage The Berhane Hewan Experience in Ethiopia; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mekbib, T.; Molla, M. Community based reproductive health (RH) intervention resulted in increasing age at marriage: The case of Berhane Hewan Project, in East Gojam zone, Amhara region, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Reprod. Health 2010, 4, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Günes, P.M. The Impact Of Female Education On Teenage Fertility: Evidence From Turkey. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 2016, 16, 259–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırdar, M.G.; Tayfur, M.D.; Koç, I. The Effect of Compulsory Schooling Laws on Teenage Marriage and Births in Turkey; IZA DP, No. 5887. 2011. Available online: http://eaf.ku.edu.tr/sites/eaf.ku.edu.tr/files/erf_wp_1035.pdf (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Hallfors, D.D.; Cho, H.; Rusakaniko, S.; Mapfumo, J.; Iritani, B.; Zhang, L.; Luseno, W.; Miller, T. The impact of school subsidies on HIV-related outcomes among adolescent female orphans. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2015, 56, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallfors, D.D.; Iritani, B.J.; Zhang, L.; Hartman, S.; Luseno, W.K.; Mpofu, E.; Rusakaniko, S. ‘I thought if I marry the prophet I would not die’: The significance of religious affiliation on marriage, HIV testing, and reproductive health practices among young married women in Zimbabwe. SAHARA J. J. Soc. Asp. HIV/AIDS Res. Alliance 2016, 13, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luseno, W.K.; Zhang, L.; Iritani, B.J.; Hartman, S.; Rusakaniko, S.; Hallfors, D.D. Influence of school support on early marriage experiences and health services utilization among young orphaned women in Zimbabwe. Health Care Women Int. 2017, 38, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallman, K.; Mubayiwa, R.; Madya, S.; Jenkins, A.; Goodman, S. Program versus Comparison Endline Survey of the Mabinti Tushike Hatamu! (Girls Lets Be Leaders!) Programme in Tanzania; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hallman, K.; Cerna-Turoff, I.; Matee, N. Participatory Research Results from Training with the Mabinti Tushike Hatamu Out-of-School Girls Program; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Handa, S.; Peterman, A.; Huang, C.; Halpern, C.; Pettifor, A.; Thirumurthy, H. Impact of the Kenya Cash Transfer for Orphans and Vulnerable Children on early pregnancy and marriage of adolescent girls. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 141, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handa, S.; Halpern, C.T.; Pettifor, A.; Thirumurthy, H. The Government of Kenya’s Cash Transfer Program Reduces the Risk of Sexual Debut among Young People Age 15–25. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, C.J.; Hoddinott, J.; Samson, M. Reducing Adolescent Risky Behaviors in a High-Risk Context: The Effects of Unconditional Cash Transfers in South Africa. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2017, 65, 619–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Social Development; South African Social Security Agency; UNICEF. Child Support Grant Evaluation 2010: Qualitative Research Report; UNICEF South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Social Development (DSD); South African Social Security Agency (SASSA); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) South Africa. The South African Child Support Grant Impact Assessment: Evidence from a Survey of Children, Adolescents and Their Households; UNICEF South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ngubane, N.; Maharaj, P. Childbearing in the context of the child support grant in a rural area in South Africa. SAGE Open 2018, 8, 2158244018817596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, C.J.; Brill, R. Stopped in the Name of the Law: Administrative Burden and its Implications for Cash Transfer Program Effectiveness. World Dev. 2015, 72, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R. Do Labor Market Opportunities Affect Young Women’s Work and Family Decisions? Experimental Evidence from India. Q. J. Econ. 2012, 127, 753–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICRW. Improving Adolescent Lives through an Integrated Program The DISHA Program in Bihar and Jharkhand, India; International Center for Research on Women (ICRW): Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Restrepo, S. The Economics of Adolescents’ Time Allocation: Evidence from the Young Agent Project in Brazil; Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Melnikas, A.J.; Saul, G.; Singh, S.K.; Mkandawire, J.; Gueye, M.; Diarra, A.; Amin, S. More Than Brides Alliance: Midline Evaluation Report; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Melnikas, A.J.; Saul, G.; Pandey, N.; Amin, S. Do Child Marriage Programs Help Girls Weather Shocks Like COVID-19? Evidence from the More Than Brides Alliance; Population Council: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Koegler, K. Gender Action Learning System in Marriage, No Child’s Play; More than Brides Alliance; Oxfam Novib: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kanungo, N. Innovative Practices: Marriage: No Child’s Play; More Than Brides Alliance: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021; Available online: https://morethanbrides.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Innovating-Practices-Marriage-No-Childs-Play.pdf#:~:text=The%20Alliance%20%28MTBA%29%20came%20into%20existence%20in%20the,girls%20by%20empowering%20informed%20decision-making%20ability%20including%20SRHR (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- Persha, L.; Magistro, J.; Baro, M. Final Report: Summative Performance Evaluation of Food for Peace Title Ii Projects Lahia, Pasam-Tai, and Sawki in Niger. 2018. Available online: https://www.google.com.sg/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwiro9H5rZj6AhUuLkQIHfRGARAQFnoECBgQAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fpdf.usaid.gov%2Fpdf_docs%2FPA00TH4D.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2sfj1ZxPypfNTM_7XTFAca (accessed on 13 January 2022).

- “Sawki” Niger Development Food Aid Program 2012–2017. 1st Quarterly Report August–December 2012; MercyCorps: Portland, OR, USA, 2013.

- Niger Development Food Aid Program “Sawki” 2012–2018. FY18 Q2 Quarterly Report January–March 2018; MercyCorps: Portland, OR, USA, 2018.

- Michielson, K.; Ivanova, O.; De Meyer, S.; Cordova, K.; Hagens, A.; Vega, B.; Chilet, E.; Segura, Z.E. Effectiveness of Complex Interventions: Post Hoc Examination of the Design, Implementation and Evaluation of the CERCA Project to Understand the Results it Achieved; Ghent University: Ghent, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova-Pozo, K.; Hoopes, A.J.; Cordova, F.; Vega, B.; Segura, Z.; Hagens, A. Applying the results based management framework to the CERCA multi-component project in adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A retrospective analysis. Reprod. Health 2018, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decat, P. Addressing the Unmet Contraceptive Need of Adolescents and Unmarried Youth: Act or Interact? Learning from Comprehensive Interventions in China and Latin America; Ghent University: Ghent, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Decat, P.; De Meye, S.; Jaruseviciene, L.; Orozco, M.; Ibarra, M.; Segura, Z.; Medina, J.; Vega, B.; Michielsen, K.; Temmerman, M.; et al. Sexual onset and contraceptive use among adolescents from poor neighbourhoods in Managua, Nicaragua. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2015, 20, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decat, P.; Nelson, E.; De Meyer, S.; Jaruseviciene, L.; Orozco, M.; Segura, Z.; Gorter, A.; Vega, B.; Cordova, K.; Maes, L.; et al. Community embedded reproductive health interventions for adolescents in Latin America: Development and evaluation of a complex multi-centre intervention. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]