The HLS19-COM-P, a New Instrument for Measuring Communicative Health Literacy in Interaction with Physicians: Development and Validation in Nine European Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

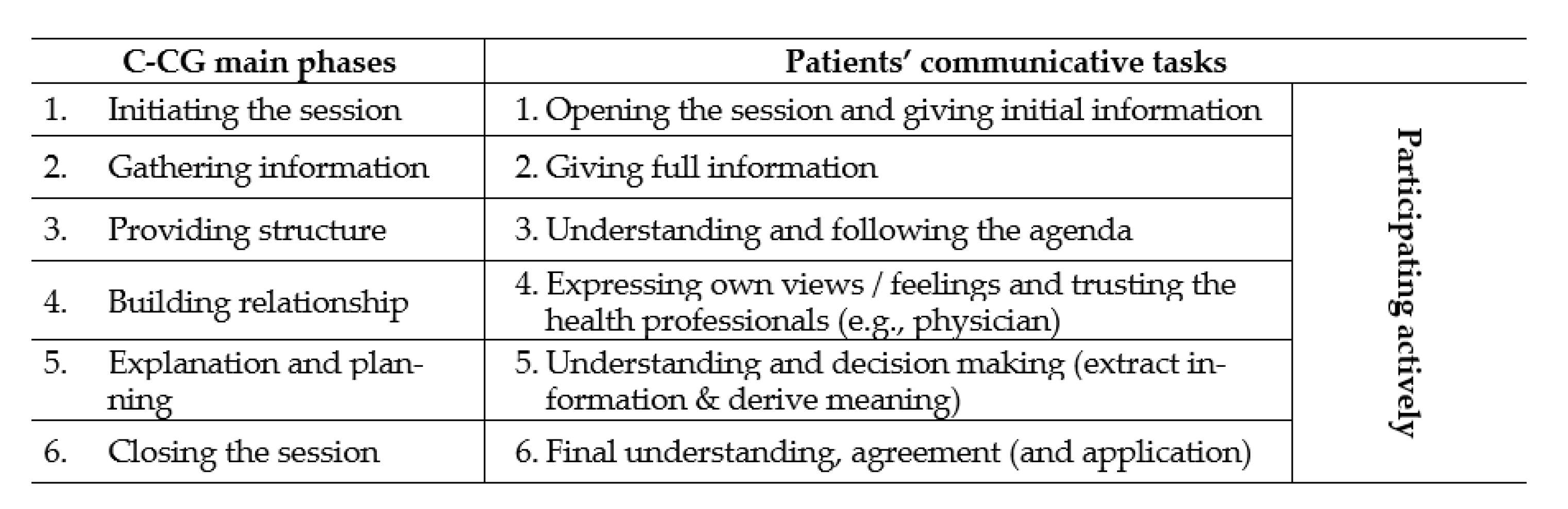

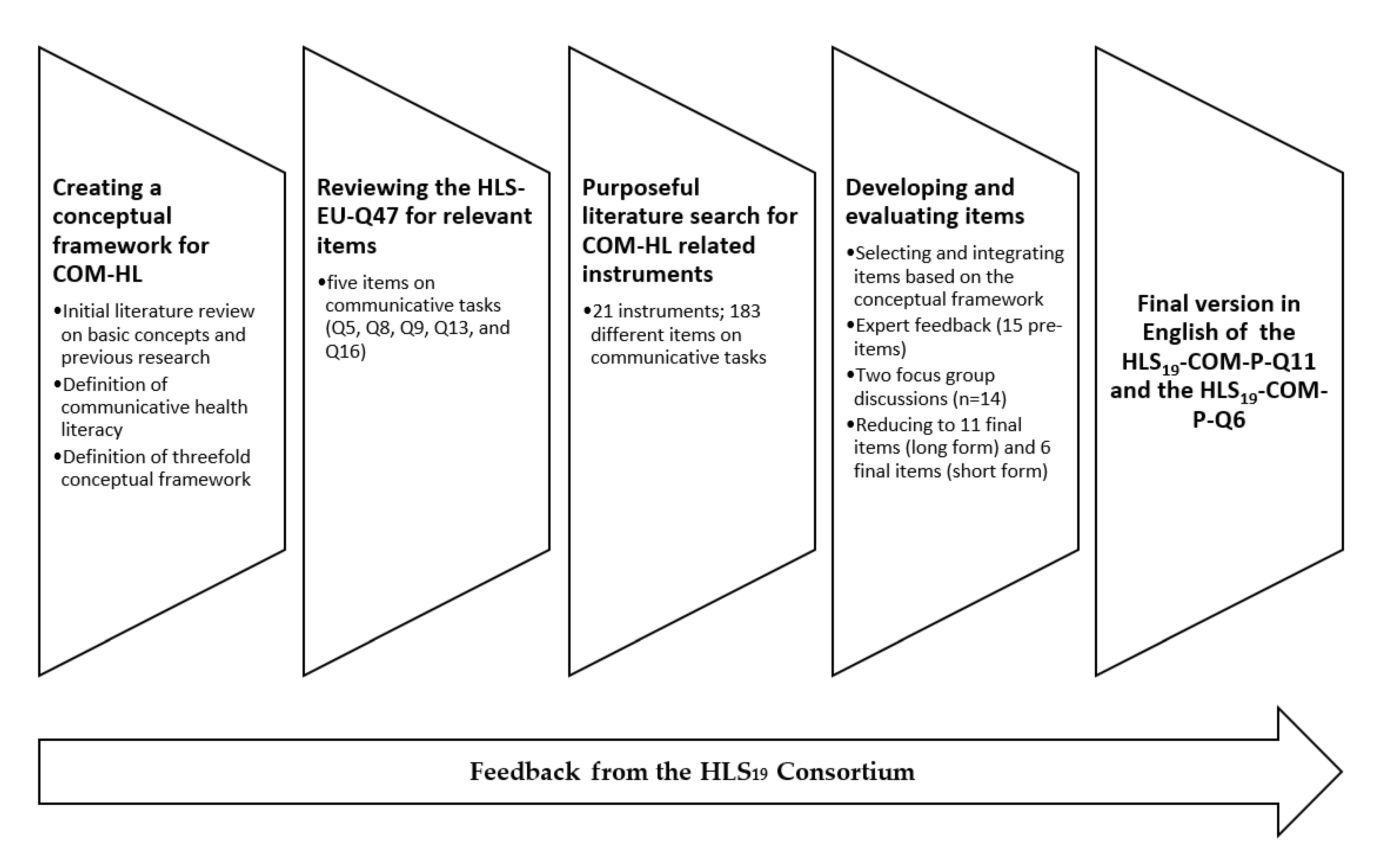

2.1. Development of the Instrument for Measuring Communicative Health Literacy in Patient–Physician Communication

2.2. Translation Process

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Analyses

2.5. Missing

3. Results

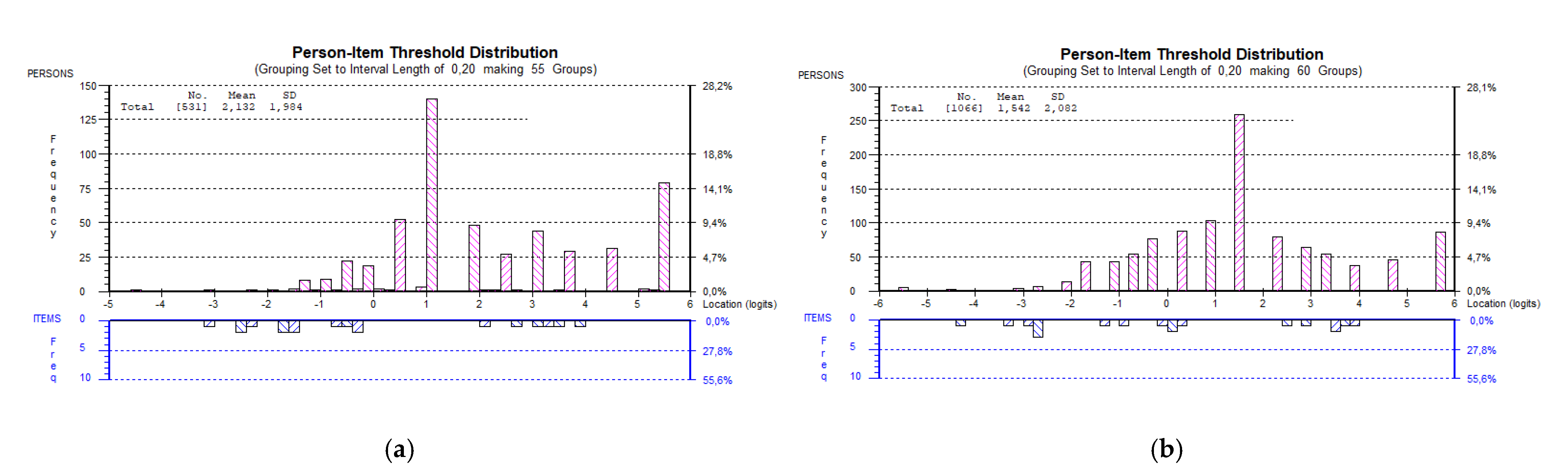

3.1. Rasch Analyses at the Overall Level

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Reliability

3.4. Fit at the Item Level

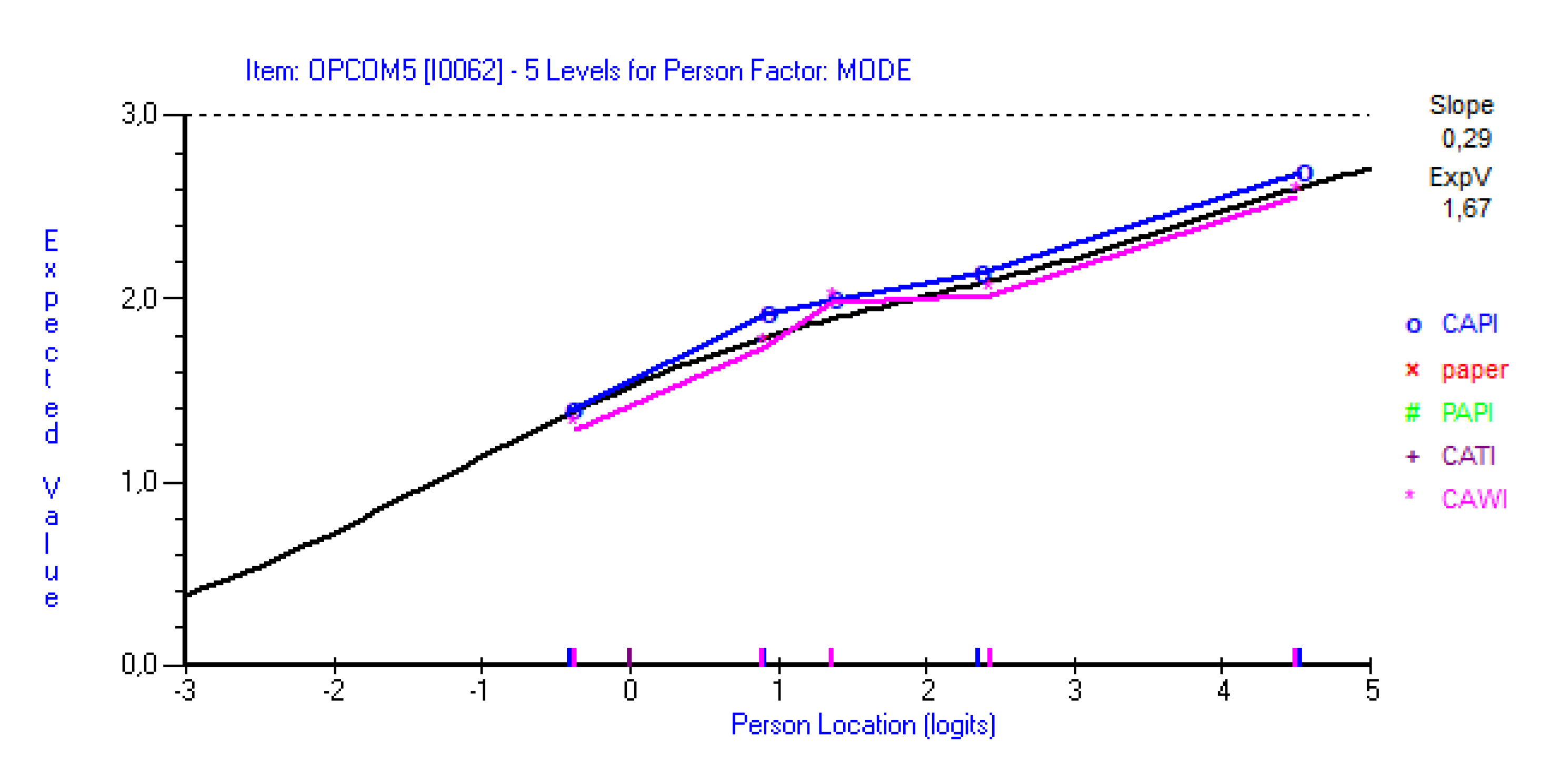

3.5. Invariance across Modes and Countries

3.6. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

3.7. Distribution of COM-HL Score

4. Discussion

4.1. Construct Validity and Reliability

4.2. Using Dichotomous or Polytomous Scores

4.3. Data Collection Mode

4.4. How to Use the Instrument

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: An updated systematic review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin-Zamir, D.; Baron-Epel, O.B.; Cohen, V.; Elhayany, A. The association of health literacy with health behavior, socioeconomic indicators, and self-assessed health from a national adult survey in Israel. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The HLS19 Consortium of the WHO Action Network M-POHL. International Report on the Methodology, Results and recommendations of the European Health Literacy Population Survey 2019–2021 (HLS19) of M-POHL; Austrian National Public Health Institute: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbosch, J.; Van den Broucke, S.; Vancorenland, S.; Avalosse, H.; Verniest, R.; Callens, M. Health literacy and the use of healthcare services in Belgium. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2016, 70, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Pelikan, J.M.; Rothlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Slonska, Z.; Doyle, G.; Fullam, J.; Kondilis, B.; Agrafiotis, D.; Uiters, E.; et al. Health literacy in Europe: Comparative results of the European health literacy survey (HLS-EU). Eur. J. Public Health 2015, 25, 1053–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, D.; Berens, E.-M.; Gille, S.; Griese, L.; Klinger, J.; de Sombre, S.; Vogt, D.; Hurrelmann, K. Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland vor und während der Corona Pandemie: Ergebnisse des HLS-GER 2; Universität Bielefeld: Bielefeld, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clever, S.L.; Jin, L.; Levinson, W.; Meltzer, D.O. Does doctor–patient communication affect patient satisfaction with hospital care? Results of an analysis with a novel instrumental variable. Health Serv. Res. 2008, 43, 1505–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langewitz, W.; Conen, D.; Nübling, M.; Weber, H. Kommunikation ist wesentlich-Defizite der Betreuung im Krankenhaus aus der Sicht von Patienten und Patientinnen. PPmP-Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 2002, 52, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, K.; Nadj-Kittler, M. Zentrale Faktoren der Patienten-und Mitarbeiterzufriedenheit; Picker Institut Deutschland gGmbH: Hamburg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, N.; Bower, P. Patient-centred consultations and outcomes in primary care: A review of the literature. Patient Educ. Couns. 2002, 48, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sator, M.; Nowak, P.; Menz, F. Verbesserung der Gesprächsqualität in der Krankenversorgung–Praxismodelle und Entwicklungsinitiativen; Gesundheit Österreich GmbH: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Street, R.L.; Makoul, G.; Arora, N.K.; Epstein, R.M. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 74, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hay, J.L.; Waters, E.A.; Kiviniemi, M.T.; Biddle, C.; Schofield, E.; Li, Y.; Kaphingst, K.; Orom, H. Health literacy and use and trust in health information. J. Health Commun. 2018, 23, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Wolf, M.S. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007, 31, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Heide, I.; Poureslami, I.; Mitic, W.; Shum, J.; Rootman, I.; FitzGerald, J.M. Health literacy in chronic disease management: A matter of interaction. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 102, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, C.M.; Wilson, C.; Wang, F.; Schillinger, D. Babel babble: Physicians’ use of unclarified medical jargon with patients. Am. J. Health Behav. 2007, 31, S85–S95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schillinger, D.; Bindman, A.; Wang, F.; Stewart, A.; Piette, J. Functional health literacy and the quality of physician–patient communication among diabetes patients. Patient Educ. Couns. 2004, 52, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, M.G.; Jacobson, T.A.; Veledar, E.; Kripalani, S. Patient literacy and question-asking behavior during the medical encounter: A mixed-methods analysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2007, 22, 782–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.K.; Nutbeam, D.; McCaffery, K.J. Insights into the concept and measurement of health literacy from a study of shared decision-making in a low literacy population. J. Health Psychol. 2013, 18, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griese, L.; Berens, E.-M.; Nowak, P.; Pelikan, J.M.; Schaeffer, D. Challenges in Navigating the Health Care System: Development of an Instrument Measuring Navigation Health Literacy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griese, L.; Schaeffer, D.; Berens, E.-M. Navigational health literacy among people with chronic illness. Chronic Illn. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 67, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Defining and measuring health literacy: What can we learn from literacy studies? Int. J. Public Health 2009, 54, 303–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Pelikan, J.; Slonska, Z.; Brand, H. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HLS-EU Consortium. Comparative Report of Health Literacy in Eight EU Member States. The European Health Literacy Survey HLS-EU (First Revisesed and Extended Version. Date 22 July 2014). 2012. Available online: http://www.health-literacy.eu (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Nowak, P.; Finbråten, H.S.; Biro, E.; Bøggild, H.; Charafeddine, R.; Mancini, J.; Griebler, R.; Griese, L.; Kucera, Z.; Link, T.; et al. Communicative Health Literacy with physicians in health care services. In International Report on the Methodology, Results, and Recommendations of the European Health Literacy Population Survey 2019–2021 (HLS19) of M-POHL; The HLS19 Consortium of the WHO Action Network M-POHL, Ed.; Austrian National Public Health Institute: Vienna, Austria, 2021; pp. 233–274. [Google Scholar]

- Nouri, S.S.; Rudd, R.E. Health literacy in the “oral exchange”: An important element of patient–provider communication. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, H.; Takeuchi, T.; Yano, E. Measuring functional, communicative, and critical health literacy among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2008, 31, 874–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinn, D.; McCarthy, C. All Aspects of Health Literacy Scale (AAHLS): Developing a tool to measure functional, communicative and critical health literacy in primary healthcare settings. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 90, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, J.; Hawkins, M.; Batterham, R.; Dodson, S.; Osborne, R.H.; Beauchamp, A. Conceptualisation and development of the conversational health literacy assessment tool (CHAT). BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverman, J.; Kurtz, S.; Draper, J. Skills for Communication with Patients, 3rd ed.; Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, E.D.; Wolderslund, M.O.; Kofoed, P.-E.; Gulbrandsen, P.; Poulsen, H.; Cold, S.; Ammentorp, J. Codebook for rating clinical communication skills based on the Calgary-Cambridge Guide. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Pelikan, J.M.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Slonska, Z.; Kondilis, B.; Stoffels, V.; Osborne, R.H.; Brand, H. Measuring health literacy in populations: Illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, E. Latent Path Models within an IRT Framework. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Petrillo, J.; Cano, S.J.; McLeod, L.D.; Coon, C.D. Using classical test theory, item response theory, and Rasch measurement theory to evaluate patient-reported outcome measures: A comparison of worked examples. Value Health 2015, 18, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.; Allen, D.D.; Li, J.C. Improving measurement in health education and health behavior research using item response modeling: Comparison with the classical test theory approach. Health Educ. Res. 2006, 21 (Suppl. 1), i19–i32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kreiner, S. The Rasch model for dichotomous items. In Rasch Models in Health; Christensen, K.B., Kreiner, S., Mesbah, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Guttersrud, Ø.; Le, C.; Pettersen, K.S.; Finbråten, H.S. Rasch Analyses of Data Collected in 17 Countries—A Technical Report to Support Decision-Making within the M-POHL Consortium, Oslo, Norway. 2021, p. 37. Available online: https://m-pohl.net/sites/m-pohl.net/files/inline-files/Guttersrud%20et%20al_Rasch%20analyses%20of%20data%20colllected%20in%2017%20countries_2021_0.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2022).

- Frisbie, D.A. Reliability of Scores From Teacher-Made Tests. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 1988, 7, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.B.; Yang, Y. Reliability of summed item scores using structural equation modeling: An alternative to coefficient alpha. Psychometrika 2009, 74, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Zulkurnain, N.N.A.; Khairushalimi, F.I. Assessing the validity and reliability of a measurement model in Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Br. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2016, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masters, G.N. A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika 1982, 47, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasch, G. Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests, Expanded ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, A.; Conaghan, P.G. The Rasch measurement model in rheumatology: What is it and why use it? When should it be applied, and what should one look for in a Rasch paper? Arthritis Care Res. 2007, 57, 1358–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagell, P. Testing rating scale unidimensionality using the principal component analysis (PCA)/t-test protocol with the Rasch model: The primacy of theory over statistics. Open J. Stat. 2014, 4, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, M.; Marais, I.; Christensen, K.B. Dimensionality. In Rasch Models in Health; Christensen, K.B., Kreiner, S., Mesbah, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 137–157. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E.V. Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimensionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. J. Appl. Meas. 2002, 3, 205–231. [Google Scholar]

- Beaujean, A.A. Latent Variable Modeling Using R: A Step-by-Step Guide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, R.E.; Lomax, R.G. A beginner′s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.D.; Linacre, J.M. Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Meas. Trans. 1994, 8, 370. [Google Scholar]

- Marais, I. Local Dependence. In Rasch Models in Health; Christensen, K.B., Kreiner, S., Mesbah, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hagquist, C.; Bruce, M.; Gustavsson, J.P. Using the Rasch model in nursing research: An introduction and illustrative example. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009, 46, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagquist, C. Explaining differential item functioning focusing on the crucial role of external information—An example from the measurement of adolescent mental health. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrich, D.; Marais, I. A Course in Rasch Measurement Theory: Measuring in the Educational, Social and Health Sciences; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, B. The large sample size fallacy. Scand. J. Caring Sci 2013, 27, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Andrich, D.; Sheridan, B. RUMM2030Plus; Rumm Laboratory Pty Ltd.: Duncraig, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.J.; Wu, M.L.; Cloney, D.; Wilson, M.R. ACER ConQuest: Generalised Item Response Modelling Software [Computer software], Version 5.; Australian Council for Educational Research: Camberwell, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, N.E.; Epel, E.S.; Castellazzo, G.; Ickovics, J.R. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychol. 2000, 19, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampert, T.; Hoebel, J.; Kuntz, B.; Müters, S.; Kroll, L.E. Messung des Sozioökonomischen Status und des Subjektiven Sozialen Status in KiGGS Welle 2; Robert Koch-Institut: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Andrich, D. Rasch Models for Measurement; SAGE: Newsbury Park, CA, USA, 1988; Volume 68. [Google Scholar]

- Masters, G.N. Item discrimination: When more is worse. J. Educ. Meas. 1988, 25, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveugele, M.; Derese, A.; van den Brink-Muinen, A.; Bensing, J.; De Maeseneer, J. Consultation length in general practice: Cross sectional study in six European countries. BMJ 2002, 325, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, H.; Liu, J.; Haynie, K.; Woo, A.; Gorham, J. Comparison between dichotomous and polytomous scoring of innovative items in a large-scale computerized adaptive test. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2012, 72, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, V.; Mannino, F.; Zhang, R. Consequences of dichotomization. Pharm. Stat. J. Appl. Stat. Pharm. Ind. 2009, 8, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCoster, J.; Iselin, A.-M.R.; Gallucci, M. A conceptual and empirical examination of justifications for dichotomization. Psychol. Methods 2009, 14, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J. Public Health 2005, 27, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braekman, E.; Charafeddine, R.; Demarest, S.; Drieskens, S.; Berete, F.; Gisle, L.; Van der Heyden, J.; Van Hal, G. Comparing web-based versus face-to-face and paper-and-pencil questionnaire data collected through two Belgian health surveys. Int. J. Public Health 2020, 65, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patients’ Communicative Tasks | Items | |

|---|---|---|

| On a Scale from Very Easy to Very Difficult, How Easy Would You Say It Is for You … | ||

| 1. Opening the session and giving initial information | COM1 | … to describe to your doctor your reasons for coming to the consultation? |

| 2. Giving full information | COM2 | … to make your doctor listen to you without being interrupted? |

| COM3 | … to explain your health concerns to your doctor? | |

| 3. Understanding and following the agenda | COM4 | … to get enough time in the consultation with your doctor? |

| 4. Expressing one’s own views and trusting | COM5 | ... to express your personal views and preferences to your doctor? |

| 5. Understanding and decision making | COM6 | … to get the information you need from your doctor? |

| COM7 | … to understand the words used by your doctor? | |

| COM8 | … to ask your doctor questions in the consultation? | |

| COM9 | ... to be involved in decisions about your health in dialogue with your doctor? | |

| 6. Final understanding and agreement | COM10 | … to recall the information you get from your doctor? |

| COM11 | … to use the information from your doctor to take care of your health? | |

| Country | Item Set | Language | Mode of Data Collection | Sampling Procedure | Period of Data Collection | Number of Respondents i |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT | Q11 | German | CATI | Multi-stage random sampling | 16 March–26 May 2020 | 2954 |

| BE | Q6 | Dutch, French | CAWI | Quota sampling | 30 January–28 February 2020; 1–26 October 2020 | 1000 |

| BG | Q6 | Bulgarian | CAPI, CAWI | Proportional stratified sampling (CAPI) and random quota sampling (CAWI) | 15 August–30 November 2020 (CAPI); 1 April–1 June 2021 (CAWI) | 859 |

| CZ | Q6 | Czech | CATI, CAWI | Random digital procedure (CATI) and random quota sampling (CAWI) | 10–24 November 2020 | 1597 |

| DE | Q11 | German | PAPI | Multi-stage random and quota sampling combined | 13 December 2019–27 January 2020 | 2133 |

| DK | Q6 | Danish | CAWI | Multi-stage random sampling | 11 December 2020–5 February 2021 | 3600 |

| FR | Q6 | French | CAWI | Quota sampling | 27 May–5 June 2020; 8–18 January 2021 | 2003 |

| HU | Q6 | Hungarian | CATI | Multi-stage random sampling | 2–20 December 2020 | 1186 |

| SI | Q11 | Slovenian | CAPI, self-administered paper and pencil ii, CAWI | Multi-stage random sampling | 9–15 March 2020; 9 June 2020–10 August 2020 | 3342 |

| Characteristic | AT | BE | BG CAPI | BG CAWI | CZ CATI | CZ CAWI | DE | DK | FR | HU | SI CAPI | SI CAWI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2954 | 1000 | 402 | 457 | 531 | 1066 | 2133 | 3600 | 2003 | 1186 | 1855 | 1487 | ||

| Gender | male | 44.2 | 49.6 | 29.6 | 24.5 | 40.7 | 51.3 | 49.6 | 43.9 | 49.2 | 47.8 | 47.0 | 45.5 | |

| female | 55.8 | 50.4 | 70.4 | 75.5 | 59.3 | 48.7 | 50.2 | 56.1 | 50.8 | 52.2 | 53.0 | 54.5 | ||

| missing | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Age # | Dichotomized | ≤45 | 34.1 | 43.9 | 60.5 | 66.5 | 18.6 | 57.0 | 38.3 | 21.7 | 48.6 | 33.6 | 28.4 | 51.8 |

| ≥46 | 65.8 | 56.1 | 37.8 | 33.5 | 81.4 | 43.0 | 60.8 | 78.3 | 51.4 | 66.4 | 71.6 | 48.2 | ||

| missing | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Categorized (1st version) | 18 to 25 years | 6.8 | 9.0 | 18.9 | 20.5 | 1.7 | 12.7 | 9.4 | 4.4 | 12.0 | 7.2 | 5.3 | 11.5 | |

| 26 to 65 years | 70.4 | 74.7 | 73.2 | 75.3 | 49.7 | 76.3 | 65.2 | 60.7 | 74.8 | 65.4 | 61.9 | 75.6 | ||

| 66 years and older | 22.7 | 16.3 | 6.2 | 4.2 | 48.6 | 11.0 | 24.5 | 34.9 | 13.2 | 27.4 | 32.8 | 12.9 | ||

| missing | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Categorized (2nd version) | 18 to 45 years | 34.1 | 43.9 | 60.5 | 66.5 | 18.6 | 57.0 | 38.3 | 21.7 | 48.6 | 33.6 | 28.4 | 51.8 | |

| 46 to 75 years | 56.3 | 53.3 | 37.1 | 32.4 | 68.0 | 41.4 | 50.0 | 69.1 | 51.4 | 57.5 | 57.9 | 44.2 | ||

| 76 years and older | 9.5 | 2.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 13.4 | 1.6 | 10.8 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 8.9 | 13.7 | 4.0 | ||

| missing | 0.1 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Highest level of completed education | Upper secondary school (ISCED 0 to 3) | 61.9 | 14.7 | 32.3 | 22.1 | 86.6 | 71.8 | 54.4 | 15.1 | 17.9 | 70.4 | 80.9 | 54.3 | |

| above | 38.1 | 84.1 | 66.2 | 77.5 | 13.2 | 28.2 | 43.5 | 84.8 | 82.1 | 29.6 | 19.1 | 45.7 | ||

| missing | 0.0 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 2.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Status of employment | employed | 59.7 | 57.7 | 81.4 | 87.8 | 34.5 | 72.5 | 60.5 | 55.2 | 67.5 | 56.9 | 44.8 | 70.3 | |

| unemployed or retired | 40.0 | 38.4 | 14.4 | 9.4 | 65.2 | 27.2 | 38.1 | 40.9 | 32.5 | 42.5 | 54.9 | 28.4 | ||

| missing | 0.3 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 2.8 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.4 | 3.9 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 1.3 | ||

| Ability to pay bills | easy | 85.8 | 62.4 | 61.5 | 63.0 | 81.4 | 67.4 | 73.7 | 92.8 | 74.6 | 67.4 | 56.2 | 61.2 | |

| difficult | 13.3 | 37.6 | 33.3 | 35.2 | 18.3 | 32.6 | 22.5 | 6.9 | 25.4 | 31.3 | 42.5 | 38.7 | ||

| missing | 0.9 | 0.0 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.1 | ||

| Self-perceived level in society (1 to 10) | level 4 or lower i | 6.8 | 10.6 | 11.7 | 9.0 | 13.9 | 17.4 | 17.3 | 11.4 | 20.3 | 26.1 | 25.9 | 20.6 | |

| level 5 or higher | 87.2 | 89.4 | 77.9 | 79.0 | 84.0 | 82.6 | 80.0 | 88.3 | 79.7 | 72.6 | 71.1 | 79.1 | ||

| missing | 6.0 | 0.0 | 10.4 | 12.0 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 3.0 | 0.3 | ||

| Self-reported general health | good or fair | 97.0 | 92.1 | 96.3 | 96.3 | 85.5 | 91.5 | 93.0 | 92.6 | 92.6 | 91.1 | 90.2 | 96.3 | |

| bad | 2.9 | 7.9 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 14.3 | 8.5 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 7.4 | 8.8 | 9.7 | 3.6 | ||

| missing | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | ||

| Q11 | Q6 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT n = 2954 | DE n = 2133 | SI n = 1856 | SI n = 1487 | AT n = 2952 | BE n = 1000 | BG n = 402 | BG n = 457 | CZ n = 531 | CZ n = 1066 | DE n = 2133 | DK n = 3600 | FR n = 2003 | HU n = 1186 | SI n = 1855 | SI n = 1487 | |

| mode | CATI | PAPI | CAPI | CAWI | CATI | CAWI | CAPI | CAWI | CATI | CAWI | PAPI | CAWI | CAWI | CATI | CAPI | CAWI |

| χ2, p | 81.5, <0.001 | 84.5, <0.001 | 94.2, <0.001 | 108.1, <0.001 | 33.2, 0.1 | 57.3, <0.001 | 62.9, <0.001 | 93.2, <0.001 | 84.4, <0.001 | 51.3, 0.001 | 34.6, 0.07 | 86.7, <0.001 | 44.5, 0.01 | 52.1, 0.001 | 45.8, 0.005 | 47.7, 0.003 |

| Mean person location | 2.57 | 1.38 | 2.55 | 2.73 | 2.39 | 2.20 | 1.34 | 1.58 | 2.13 | 1.54 | 1.21 | 1.97 | 1.85 | 1.88 | 2.36 | 2.47 |

| Dimensionality, % (lower 95% CI proportion) | 6.1 (5.3) | 7.9 (7.0) | 4.8 (3.8) | 6.9 (5.8) | 5.3 (4.5) | 4.4 (3.0) | 6.5 (4.4) | 5.3 (3.3) | 5.8 (4.0) | 5.1 (3.8) | 5.0 (4.1) | 7.5 (6.7) | 3.6 (2.6) | 3.0 (1.7) | 3.0 (2.0) | 4.4 (3.3) |

| Q11 | Q6 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fit-Indices | AT n = 2766 | DE n = 2064 | SI n = 1781 | SI n = 1471 | AT n = 2827 | BE n = 1000 | BG n = 333 | BG n = 394 | CZ n = 504 | CZ n = 1066 | DE n = 2101 | DK n = 3574 | FR n = 2003 | HU n = 1125 | SI n = 1788 | SI n = 1477 | |

| mode | CATI | PAPI | CAPI | CAWI | CATI | CAWI | CAPI | CAWI | CATI | CAWI | PAPI | CAWI | CAWI | CATI | CAPI | CAWI | |

| SRMR | polytomous data | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| dichotomous data | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.03 | |

| RMSEA | polytomous data | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| dichotomous data | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| RMSEA; CI, lower | polytomous data | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| dichotomous data | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| RMSEA; CI, upper | polytomous data | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| dichotomous data | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.03 | |

| RMSEA; p-value | polytomous data | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.18 | 0.79 | 0.91 | 0.02 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 1.00 | 0.02 |

| dichotomous data | 1.00 | 0.16 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.80 | 0.71 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| CFI | polytomous data | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| dichotomous data | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| TLI | polytomous data | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| dichotomous data | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| GFI | polytomous data | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| dichotomous data | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| AGFI | polytomous data | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| dichotomous data | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Q11 | Q6 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT CATI | DE PAPI | SI CAPI | SI CAWI | AT CATI | BE CAWI | BG CAPI | BG CAWI | CZ CATI | CZ CAWI | DE PAPI | DK CAWI | FR CAWI | HU CATI | SI CAPI | SI CAWI | ||

| Person separation index | polytomous data i | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.78 | 0.79 |

| dichotomous data ii | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Cronbach’s alpha | polytomous data | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.89 |

| dichotomous data | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.79 | |

| Omega | polytomous data | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| dichotomous data | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.82 | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.81 | |

| Average variance extracted | polytomous data | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.57 | 0.71 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.73 | 0.70 |

| dichotomous data | 0.55 | 0.57 | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.70 | |

| Q11 | Q6 | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AT n = 2954 | DE n = 2133 | SI n = 1856 | SI n = 1487 | AT n = 2952 | BE n = 1000 | BG n = 402 | BG n = 457 | CZ n = 531 | CZ n = 1066 | DE n = 2133 | DK n = 3600 | FR n = 2003 | HU n = 1186 | SI n = 1855 | SI n = 1487 | ||

| mode | CATI | PAPI | CAPI | CAWI | CATI | CAWI | CAPI | CAWI | CATI | CAWI | PAPI | CAWI | CAWI | CATI | CAPI | CAWI | |

| GEN-HL | polytomous data | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.51 |

| dichotomous data | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.46 | 0.53 | 0.39 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.52 | 0.36 | 0.49 | 0.41 | |

| HL-NAV | polytomous data | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.56 | 0.44 | - | - | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.54 | - | 0.51 | - | 0.54 | 0.52 |

| dichotomous data | 0.49 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.36 | - | - | 0.38 | 0.45 | 0.45 | - | 0.44 | - | 0.48 | 0.41 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Finbråten, H.S.; Nowak, P.; Griebler, R.; Bíró, É.; Vrdelja, M.; Charafeddine, R.; Griese, L.; Bøggild, H.; Schaeffer, D.; Link, T.; et al. The HLS19-COM-P, a New Instrument for Measuring Communicative Health Literacy in Interaction with Physicians: Development and Validation in Nine European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811592

Finbråten HS, Nowak P, Griebler R, Bíró É, Vrdelja M, Charafeddine R, Griese L, Bøggild H, Schaeffer D, Link T, et al. The HLS19-COM-P, a New Instrument for Measuring Communicative Health Literacy in Interaction with Physicians: Development and Validation in Nine European Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811592

Chicago/Turabian StyleFinbråten, Hanne Søberg, Peter Nowak, Robert Griebler, Éva Bíró, Mitja Vrdelja, Rana Charafeddine, Lennert Griese, Henrik Bøggild, Doris Schaeffer, Thomas Link, and et al. 2022. "The HLS19-COM-P, a New Instrument for Measuring Communicative Health Literacy in Interaction with Physicians: Development and Validation in Nine European Countries" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811592

APA StyleFinbråten, H. S., Nowak, P., Griebler, R., Bíró, É., Vrdelja, M., Charafeddine, R., Griese, L., Bøggild, H., Schaeffer, D., Link, T., Kucera, Z., Mancini, J., & Pelikan, J. M. (2022). The HLS19-COM-P, a New Instrument for Measuring Communicative Health Literacy in Interaction with Physicians: Development and Validation in Nine European Countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11592. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811592