Formative Qualitative Research: Design Considerations for a Self-Directed Lifestyle Intervention for Type-2 Diabetes Patients Using Human-Centered Design Principles in Benin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

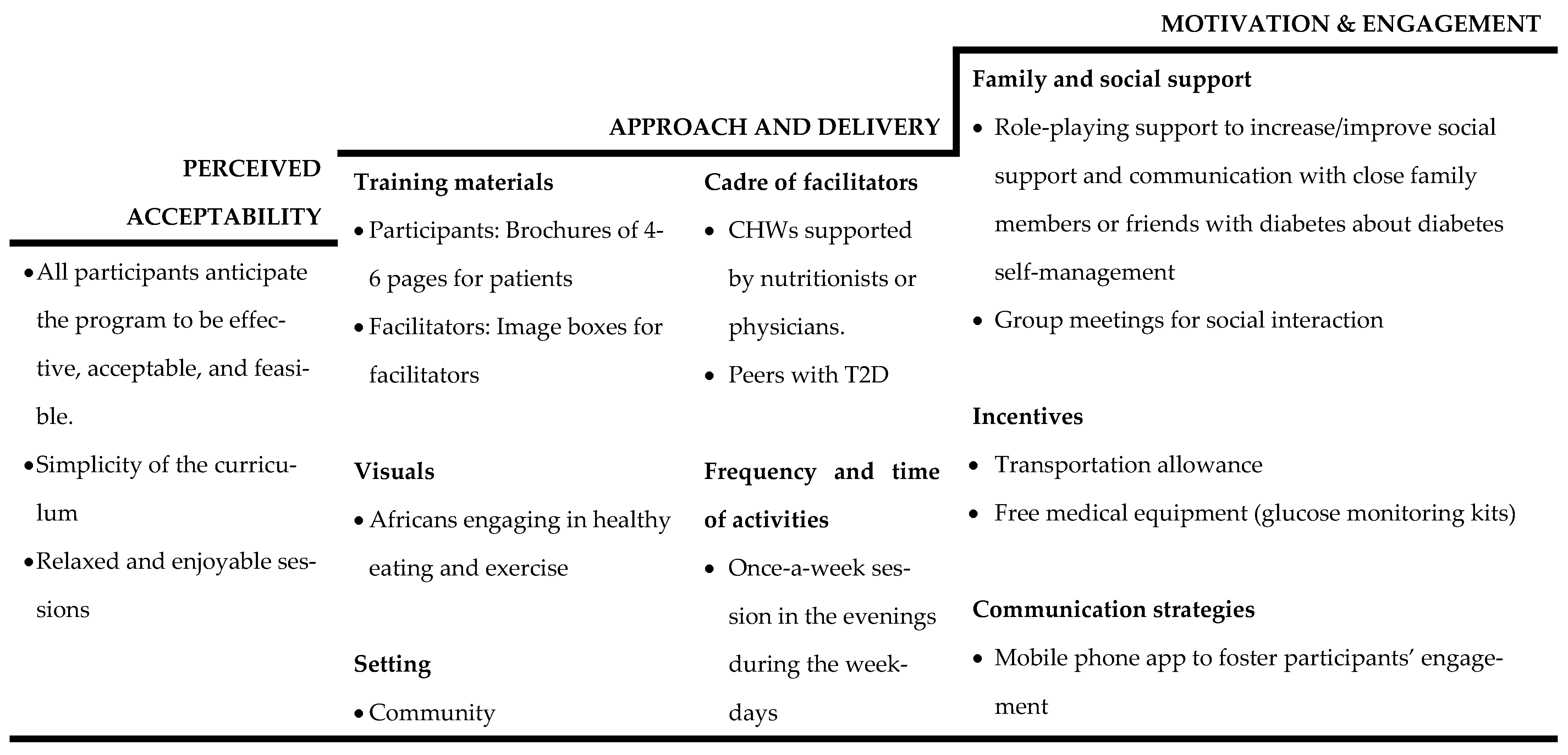

3.1. Approach and Delivery

- Subtheme 1: Module brochure and training materials

“I agree with an information brochure of three or four pages that can help us revise everything that has happened.”—Patient focus group

“In the village, if they see someone who looks like them doing the exercises [in the brochure], they automatically think they can do them.”—Community partner focus group

- Subtheme 2: Facilitator characteristics

“CHWs [should be facilitators] since they are a link between the doctor and the population. They will have the doctor’s information and know-how to interact with the population. They also know what is going on.”—Community Partner Focus Group

- Subtheme 3: Location of training and activities

“The hospital in the collective mind is a dying place [a place where people die]—so you will not see many people.”—Community Partner Focus Group

- Subtheme 4: Proposed frequency and time of program activities

“I think once a week for two hours is okay if it is a participatory session. If you invite people for an hour each day, twice a week, it already takes time [to attend one meeting]”—Patient Focus Group

- Subtheme 5: Communication strategies

“[We need to] have a forum on WhatsApp where we can communicate, and we can advise each other, and if you have any concerns, we can share this.”—Patient Focus Group

3.2. Motivation and Engagement

“Results [including] health improvements that we [participants] will observe will motivate and encourage us to attend the meetings until the end.”—Patient Focus Group

- Subtheme 1: Participation

“I prefer participants to be people who have diabetes or my family.”—Patient Focus Group.

- Subtheme 2: Incentives

“I think that incentives such as free medical equipment to use [glucometers and blood tests] can also motivate them. Transportation costs too.”—Academic Partner Focus Group

3.3. Perceived Acceptability

“No problem, if the questions are understandable and there are answers to be ticked, and these are simple reports to present”—Patient Focus Group

4. Discussion

- Strengths and limitations of the study

- Implications for developing the community-based MSD in the Benin context

- Format: Program participants value group learning format as a supportive measure and shared experiences even within a self-directed diabetes management curriculum. Groups can integrate naturally occurring societal influences into the program and provide channels for developing key processes within communities [53]. However, this kind of family- and community-oriented approach will also inevitably require making at least some of the group sessions available to other family members to attend and be involved. Additionally, peer-to-peer influences could be developed naturally to provide encouragement and assistance in reaching those who otherwise might not avail themselves of the program [53]. These factors provide a strong rationale for a peer support model, as has been recently proposed [53].

- Strategy: Program participants value a mixture of materials, such as audiovisuals, mobile phone applications, and written materials, to deliver interventions. They preferred materials to be pictorials and in local languages within the intervention context. As such, cultural adaptations of Benin foods with pictorial preparation guides and physical activities will be acceptable in the country. It will be crucial to use participatory research methods to engage patients and community residents in adapting to the community health worker’s guidelines and tools for recommended activities so that they are linguistically and culturally appropriate, including guidelines for food consumption using locally available foods. These adaptations will need to use more graphics and photographs to be suitable for low-literacy participants.

- Delivery: Participants perceived community health workers (CHWs) to be the most effective in delivering the intervention, but they needed specialists like dieticians and clinicians who could co-facilitate certain aspects of the curriculum, suggesting a team leadership approach to the program delivery. For example, a trained diabetic educator (DE) can lead the didactic portions of group sessions, concentrating on the presentation of clinical and management aspects of diabetes and hypertension. Like CHWs already supporting families in improving maternal and child health outcomes in Benin, they will have responsibility for leading the group activities; role plays, demonstrations, and any community activities, as well as home visits and one-on-one visits support of participants. The training materials will need to be prepared in French, but the CHWs and DEs will be trained in presenting them in French and the local languages.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045, Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. 2015 WHO STEPwise Approach to Surveillance (STEPS); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland.

- Adeya, G.; Bigirimana, A.; Cavanaugh, K.; Franco, L.M. Rapid Assessment of the Health System in Benin. International Development Health Journal. 2011. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242451622 (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Pastakia, S.D.; Pekny, C.R.; Manyara, S.M.; Fischer, L. Diabetes in sub-Saharan Africa—from policy to practice to progress: Targeting the existing gaps for future care for diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2017, 10, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alassani, A.; Dovonou, C.; Gninkoun, J.; Wanvoegbe, A.; Attinsounon, C.; Codjo, L.; Zannou, M.; Djrolo, F.; Houngbe, F. Perceptions et pratiques des diabétiques face au diabete sucre au Centre National Hospitalier et Universitaire Hubert Koutoucou Maga (CNHU-HKM) de Cotonou. Le Mali Med. 2017, 32, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Dramé, M.L.; Mizéhoun-Adissoda, C.; Amidou, S.; Sogbohossou, P.; Paré, R.; Ekambi, A.; Houehanou, C.; Houinato, D.; Gyselinck, K.; Marx, M.; et al. Diabetes and Its Treatment Quality in Benin (West Africa): Analysis of Data from the STEPS Survey 2015. Open J. Epidemiol. 2018, 08, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Benin. 2017. Available online: http://www.healthdata.org/benin (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013, a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015, 385, 117–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwibedi, C.; Mellergård, E.; Gyllensten, A.C.; Nilsson, K.; Axelsson, A.S.; Bäckman, M.; Sahlgren, M.; Friend, S.H.; Persson, S.; Franzén, S.; et al. Effect of self-managed lifestyle treatment on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanghani, N.B.; Parchwani, D.N.; Palandurkar, K.M.; Shah, A.M.; Dhanani, J.V. Impact of lifestyle modification on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 17, 1030-9. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, E.M.; Van Regenmortel, T.; Vanhaecht, K.; Sermeus, W.; Van Hecke, A. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 1923–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumah, E.; Otchere, G.; Ankomah, S.E.; Fusheini, A.; Kokuro, C.; Aduo-Adjei, K.; Amankwah, J.A. Diabetes self-management education interventions in the WHO African Region: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. Design thinking. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 84–92, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomin, J. What Is Human Centred Design? Des. J. 2014, 17, 606–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzini, E. Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for SOCIAL Innovation; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015; Volume xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Design Kit [Internet]. Available online: https://www.designkit.org/resources/1 (accessed on 24 February 2022).

- Yu, C.H.; A Parsons, J.; Hall, S.; Newton, D.; Jovicic, A.; Lottridge, D.; Shah, B.R.; E Straus, S. User-centered design of a web-based self-management site for individuals with type 2 diabetes—Providing a sense of control and community. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2014, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, V.A.; Barr, K.L.; An, L.C.; Guajardo, C.; Newhouse, W.; Mase, R.; Heisler, M. Community-based participatory research and user-centered design in a diabetes medication information and decision tool. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2013, 7, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fico, G.; Fioravanti, A.; Arredondo, M.T.; Leuteritz, J.P.; Guillen, A.; Fernandez, D. A user centered design approach for patient interfaces to a diabetes IT platform. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS [Internet], Boston, MA, USA, 30 August–3 September 2011; pp. 1169–1172. [Google Scholar]

- Pike, J.M.; Moore, C.M.; Yazel, L.G.; O Lynch, D.; Haberlin-Pittz, K.M.; E Wiehe, S.; Hannon, T.S. Diabetes prevention in adolescents: Co-design study using human-centered design methodologies. J. Particip. Med. 2021, 13, e18245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheson, G.O.; Pacione, C.; Shultz, R.K.; Klügl, M. Leveraging human-centered design in chronic disease prevention. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2015, 48, 472–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, M.; McMahon, S.A.; Prober, C.; Bärnighausen, T. Human-centered design of video-based health education: An iterative, collaborative, community-based approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bénin 2017–2018 Enquête Démographique et de Santé. Available online: https://instad.bj/images/docs/insae-statistiques/enquetes-recensements/EDS/2017-2018/1.Benin_EDSBV_Rapport_final.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Human Development Report 2020 The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene Briefing Note for Countries on the 2020 Human Development Report. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/data (accessed on 6 June 2021).

- Denman, C.A.; Rosales, C.; Cornejo, E.; Bell, M.L.; Munguía, D.; Zepeda, T.; Carvajal, S.; Guernsey de Zapien, J. Evaluation of the community-based chronic disease prevention program Meta Salud in Northern Mexico, 2011–2012. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2014, 11, 140218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Rosales, C.B.; Denman, C.A.; Bell, M.L.; Cornejo, E.; Ingram, M.; Del Carmen Castro Vásquez, M.; Gonzalez-Fagoaga, J.E.; Aceves, B.; Nuño, T.; Anderson, E.J.; et al. Meta Salud Diabetes for cardiovascular disease prevention in Mexico: A cluster-randomized behavioral clinical trial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 50, 1272–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.O.; Velicer, W.F. The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am. J. Health Promot. 1997, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani-Alavijeh, F.; Araban, M.; Koohestani, H.R.; Karimy, M. The effectiveness of stress management training on blood glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2018, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, N.; Bryant-Lukosius, D.; DiCenso, A.; Blythe, J.; Neville, A.J. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2014, 41, 545–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VERBI Software. MAXQDA 2020. Software. 2019. Available online: https://www.maxqda.com/blogpost/how-to-cite-maxqda (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard & Thacker, Effective Training, 5th Edition|Pearson. Available online: https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/program/Blanchard-Effective-Training-5th-Edition/PGM122163.html (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Egede, L.E.; Osborn, C.Y. Role of motivation in the relationship between depression, self-care, and glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yardley, L.; Spring, B.J.; Riper, H.; Morrison, L.G.; Crane, D.H.; Curtis, K.; Merchant, G.C.; Naughton, F.; Blandford, A. Understanding and Promoting Effective Engagement with Digital Behavior Change Interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, M.T.; Sidani, S.; Brooks, D.; McCague, H. Perceived acceptability and preferences for low-intensity early activity interventions of older hospitalized medical patients exposed to bed rest: A cross sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaofè, H.; Asaolu, I.; Ehiri, J.; Moretz, H.; Asuzu, C.; Balogun, M.; Abosede, O.; Ehiri, J. Community Health Workers in Diabetes Prevention and Management in Developing Countries. Ann. Glob. Health 2017, 83, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baig, A.A.; Benitez, A.; Quinn, M.T.; Burnet, D.L. Family interventions to improve diabetes outcomes for adults. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1353, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, L.; Tullio, A.; Perri, G.; Lesa, L.; Grillone, L.; Menegazzi, G.; Pipan, C.; Valent, F.; Brusaferro, S.; Parpinel, M. Peer education for medical students on health promotion and clinical risk management. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2020, 9, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Wollny, A.; Altiner, A.; Daubmann, A.; Drewelow, E.; Helbig, C.; Löscher, S.; Pentzek, M.; Santos, S.; Wegscheider, K.; Wilm, S.; et al. Patient-centered communication and shared decision making to reduce HbA1c levels of patients with poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus - Results of the cluster-randomized controlled DEBATE trial. BMC Fam. Pract. 2019, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Zuniga, J. Effectiveness of using picture-based health education for people with low health literacy: An integrative review. Cogent Med. 2016, 3, 1264679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. Development and pilot test of pictograph-enhanced breast health-care instructions for community-residing immigrant women. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2012, 18, 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, R.M. Improving Health by Improving Health Literacy. Public Health Rep. 2010, 125, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Hawley, N.L.; Kalyesubula, R.; Siddharthan, T.; Checkley, W.; Knauf, F.; Rabin, T.L. Challenges to hypertension and diabetes management in rural Uganda: A qualitative study with patients, village health team members, and health care professionals. Int. J. Equity Health 2019, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwine, F.; Hjelm, K. Healthcare-seeking behavior and management of type 2 diabetes: From Ugandan traditional healers’ perspective. Int. J. Afr. Nurs. Sci. 2016, 5, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, M.J. The State of Health System(s) in Africa: Challenges and Opportunities. Hist. Perspect. State Health Health Syst. Afr. 2017, II, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Simacek, K.F.; Nelson, T.; Miller-Baldi, M.; Bolge, S.C. Patient engagement in type 2 diabetes mellitus research: What patients want. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2018, 12, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J.R.; Vazquez-Benitez, G.; Taylor, G.; Johnson, S.; Anderson, J.; Garrett, J.E.; Gilmer, T.; Vue-Her, H.; Rinn, S.; Engel, K.; et al. The effects of financial incentives on diabetes prevention program attendance and weight loss among low-income patients: The We Can Prevent Diabetes cluster-randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Ortiz, K.; Lira-Mendiola, G.; Gómez-Navarro, C.M.; Padilla-Estrada, K.; Angulo-Romero, F.; Hernández-Márquez, J.M.; Villa-Martínez, A.K.; González-Mena, J.N.; Macías-Cervantes, M.H.; Reyes-Escogido, M.D.L.; et al. Effect of a family and interdisciplinary intervention to prevent T2D: Randomized clinical trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musoke, P.; Gakumo, A.C.; Abuogi, L.L.; Akama, E.; Bukusi, E.; Helova, A.; Nalwa, W.Z.; Onono, M.; Spangler, S.A.; Wanga, I.; et al. A Text Messaging Intervention to Support Option B+ in Kenya: A Qualitative Study. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2018, 29, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- al Omar, M.; Hasan, S.; Palaian, S.; Mahameed, S. The impact of a self-management educational program coordinated through whatsapp on diabetes control. Pharm. Pract. 2020, 18, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronen, K.; Unger, J.A.; Drake, A.L.; Perrier, T.; Akinyi, P.; Osborn, L.; Matemo, D.; O’Malley, G.; Kinuthia, J.; John-Stewart, G. SMS messaging to improve ART adherence: Perspectives of pregnant HIV-infected women in Kenya on HIV-related message content. AIDS Care 2018, 30, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, E.B.; Boothroyd, R.I.; Coufal, M.M.; Baumann, L.C.; Mbanya, J.C.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J.; Sanguanprasit, B.; Tanasugarn, C. Peer support for self-management of diabetes improved outcomes in international settings. Health Aff. 2012, 31, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alaofè, H.; Okechukwu, A.; Yeo, S.; Magrath, P.; Amoussa Hounkpatin, W.; Ehiri, J.; Rosales, C. Formative Qualitative Research: Design Considerations for a Self-Directed Lifestyle Intervention for Type-2 Diabetes Patients Using Human-Centered Design Principles in Benin. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811552

Alaofè H, Okechukwu A, Yeo S, Magrath P, Amoussa Hounkpatin W, Ehiri J, Rosales C. Formative Qualitative Research: Design Considerations for a Self-Directed Lifestyle Intervention for Type-2 Diabetes Patients Using Human-Centered Design Principles in Benin. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811552

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlaofè, Halimatou, Abidemi Okechukwu, Sarah Yeo, Priscilla Magrath, Waliou Amoussa Hounkpatin, John Ehiri, and Cecilia Rosales. 2022. "Formative Qualitative Research: Design Considerations for a Self-Directed Lifestyle Intervention for Type-2 Diabetes Patients Using Human-Centered Design Principles in Benin" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811552

APA StyleAlaofè, H., Okechukwu, A., Yeo, S., Magrath, P., Amoussa Hounkpatin, W., Ehiri, J., & Rosales, C. (2022). Formative Qualitative Research: Design Considerations for a Self-Directed Lifestyle Intervention for Type-2 Diabetes Patients Using Human-Centered Design Principles in Benin. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11552. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811552