Prevalence and Impact of Academic Violence in Medical Education

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design/Study Population/Data Collection

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Data Collection Instrument

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive Analysis

2.5. Association

2.6. Logistic Regression

3. Results

3.1. Response Rate and Sociodemographic and Student Characterization of the Participants

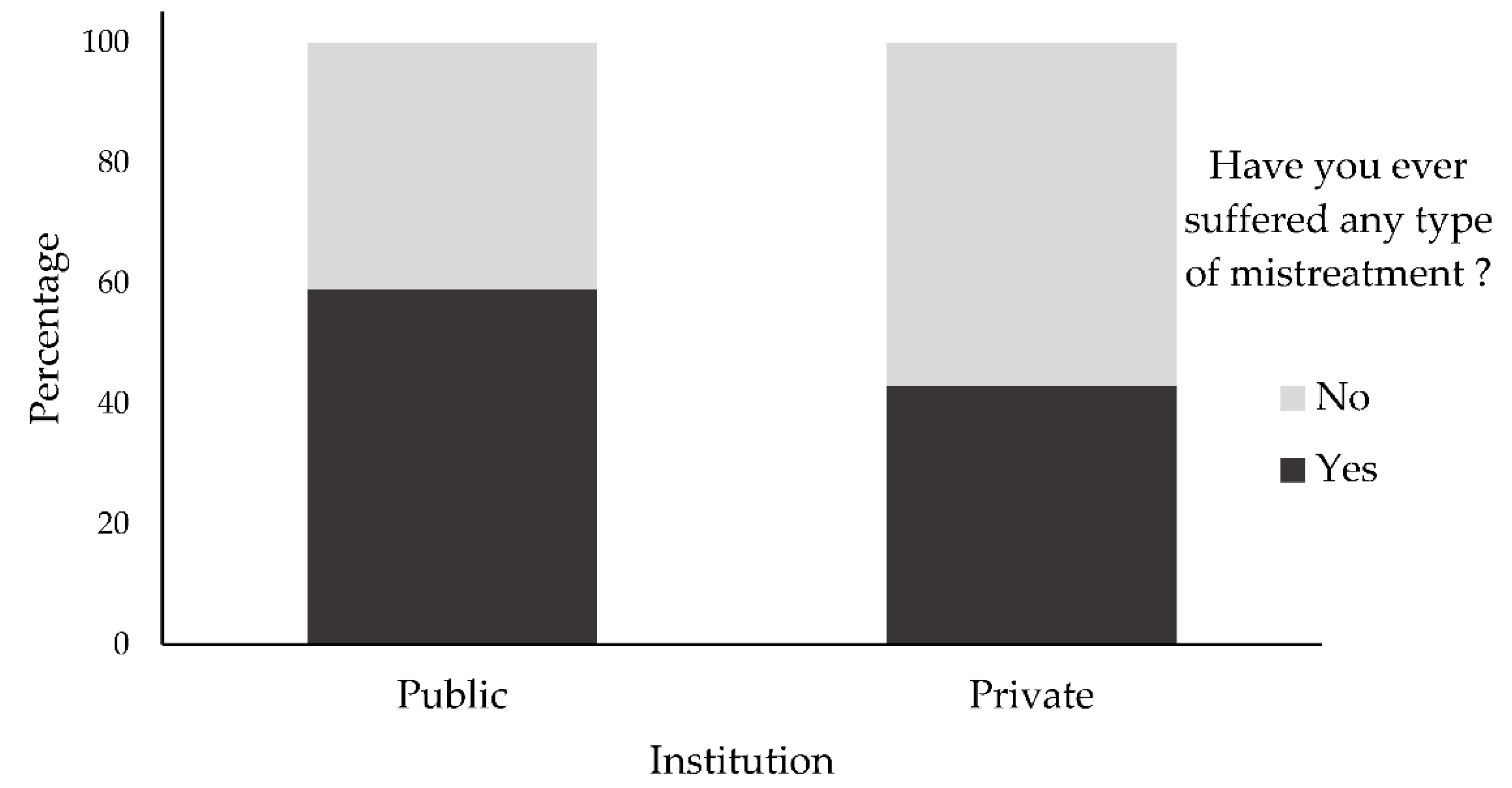

3.2. Situations Characterizing Mistreatment

3.3. Associations between the Students’ Characteristics and the Chances of Suffering Mistreatment

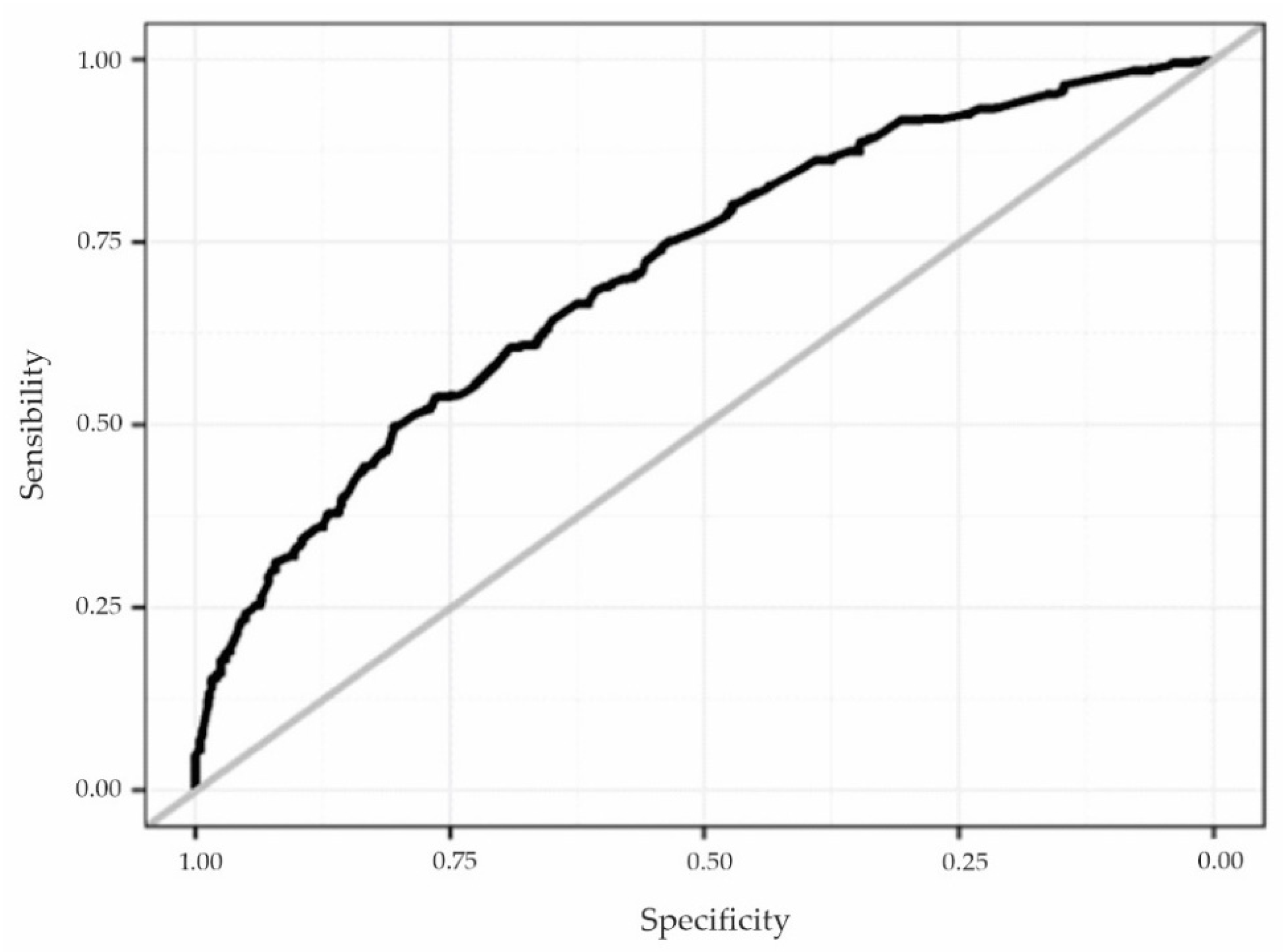

3.4. Analysis of the Quality of the Adjustment of the Multivariate Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Silver, H.K. Medical students and medical school. JAMA 1982, 247, 309–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.Y.; Ellis, R.J.; Hewitt, D.B.; Yang, A.D.; Cheung, E.O.; Moskowitz, J.T.; Potts, J.R.; Buyske, J.; Hoyt, D.B.; Nasca, T.J.; et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency academic medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1741–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askew, D.A.; Schluter, P.J.; Dick, M.L.; Régo, P.M.; Turner, C.; Wilkinson, D. Bullying in the Australian Medical Workforce: Cross data from an Australian e-Cohort study. Aust. Health Rev. 2012, 36, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, J.; Blanshard, C.; Child, S. Workplace bullying of junior doctors: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. N. Z. Med. J. 2008, 121, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Finucane, P.; O’Dowd, T. Working and training as an intern: A national survey of Irish interns. Med. Teach. 2005, 27, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, A.D.L.; Babler, F.; Quaresma, I.Y.V.; Arakaki, J.N.L.; Peres, M.F.T. Projeto QUARA—Prevalência de abusos, maus-tratos e outras agressões durante a formação médica: Um estudo de corte transversal em São Paulo, Brasil, 2013. Rev. Med. 2015, 94, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata-Kobayashi, S.; Maeno, T.; Yoshizu, M.; Shimbo, T. Universal problems during residency: Abuse and harassment. Med. Educ. 2009, 43, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautio, A.; Sunnari, V.; Nuutinen, M.; Laitala, M. Mistreatment of university students most common during medical studies. BMC Med Educ. 2005, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akanni, D.W.M.; Adjadohoun, S.B.G.; Damien, B.G.; Tognon-Tchegnonsi, F.; Allode, A.; Aubrege, A.; de Tove, K.M.S. Maltraitance des étudiants et facteurs associés à la Faculté de Médecine de Parakou em 2018. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2019, 34, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, S.; Anis, M.; Kella, D.K.; Qazi, F.; Samad, F.; Mir, F.; Mansoor, M.; Paryez, M.B.; Osmani, B.; Panju, S.A.; et al. Prevalence of mistreatment or belittlement among medical students—A cross sectional survey at a private medical school in Karachi, Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysola, J.; Barg, F.K.; Martinez, A.B.; Kearney, M.; Agesa, K.; Carmona, C.; Higginbotham, E. Perceptions of factors associated with inclusive work and learning environments in health care organizations: A qualitative narrative analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e181003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoaje, E.T.; Uchendu, O.C.; Ige, O.K. Experiences of mistreatment among medical students in a university in southwest Nigeria. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 15, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, A.E.; Smith, S. Mistreatment of Medical Trainees: Time for a New Approach. JAMA Netw. Open 2018, 1, e180869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fnais, N.; Soobiah, C.; Chen, M.H.; Lillie, E.; Perrier, L.; Tashkhandi, M.; Straus, S.E.; Mamdani, M.; Al-Omran, M.; Tricco, A.C. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad. Med. 2014, 89, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IBGE, Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Projeção da População do Brasil e das Unidades da Federação. 2022. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/apps/populacao/projecao/index.html (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Sheskin, D.J. Handbook of Parametric and Nonparametric Statistical Procedures, 3rd ed.; Chapman & Hall/CRC: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Goodness-of-fit test for the multiple logistic regression model. Commun. Stat. 1980, 9, 1043–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2015; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Scherer, Z.A.P.; Scherer, E.A.; Rossi, P.T.; Vedana, K.G.G.; Cavalin, L.A. Manifestação de violência no ambiente universitário: O olhar de acadêmicos de enfermagem. Rev. Eletrônica Enferm. 2015, 17, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olasoji, H.O. Broadening conceptions of medical student mistreatment during clinical teaching: Message from a study of “toxic” phenomenon during bedside teaching. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, 9, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, J.M.; Vermillion, M.; Parker, N.H.; Uijtdehaage, S. Eradicating medical student mistreatment: A longitudinal study of one institution’s efforts. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, M.D.; Bilimoria, K.Y.; Lu, D.W.; Zhan, T.; Barton, M.A.; Hu, Y.Y.; Beeson, M.S.; Adams, J.G.; Nelson, L.S.; Baren, J.M. Prevalence of Discrimination, Abuse, and Harassment in Emergency Medicine Residency Training in the US. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2121706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacramento, B.O.; Anjos, T.L.; Barbosa, A.G.L.; Tavares, C.F.; Dias, J.P. Sintomas de ansiedade e depressão entre estudantes de medicina: Estudo de prevalência e fatores associados. Rev. Bras. Educ. Med. 2021, 45, e021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shafaee, M.; Al-Kaabi, Y.; Al-Farsi, Y.; White, G.; Al-Maniri, A.; Al-Sinawi, H.; Al-Adawi, S. Pilot study on the prevalence of abuse and mistreatment during clinical internship: A cross-sectional study among first year residents in Oman. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Assari, S.; Lankarani, M.M. Violence Exposure and Mental Health of College Students in the United States. Behav. Sci. 2018, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres, M.F.T.; Babler, F.; Arakaki, J.N.L.; Quaresma, I.Y.V.; Barreto, A.D.L.; Silva, A.T.C.; Eluf-Neto, J. Mistreatment in an academic setting and medical students’ perceptions about their course in São Paulo, Brazil: A cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2016, 134, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristoffersson, E.; Andersson, J.; Bengs, C.; Hamberg, K. Experiences of the gender climate in clinical training—A focus group study among Swedish medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2016, 16, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuriwo, R.; Patel, Y.; Webb, K.; Bullock, A. ‘Man up’: Medical students’ perceptions of gender and learning in clinical practice: A qualitative study. Med. Educ. 2020, 54, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrelli, P.; Nyer, M.; Yeung, A.; Zulauf, C.; Wilens, T. College Students: Mental Health Problems and Treatment Considerations. Acad. Psychiatry 2015, 39, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riskin, A.; Erez, A.; Foulk, T.A.; Kugelman, A.; Gover, A.; Shoris, I.; Riskin, K.S.; Bamberger, P.A. The impact of rudeness on medical team performance: A randomized trial. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.P.; Thang, C.K.; Vermillion, M.; Fried, J.M.; Uijtdehaage, S. Exploring medical students’ barriers to reporting mistreatment during clerkships: A qualitative study. Med. Educ. Online 2018, 23, 1478170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAMC, Association of Medical Colleges. Medical School Graduation Questionnaire. 2016. Available online: https://www.aamc.org/download/464412/data/2016gqallschoolssummaryreport.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Castillo-Angeles, M.; Watkins, A.A.; Acosta, D.; Frydman, J.L.; Flier, L.; Garces-Descovich, A.; Cahalane, M.J.; Gangadharan, S.P.; Atkins, K.M.; Kent, T.S. Mistreatment and the learning environment for medical students on general surgery clerkship rotations: What do key stakeholders think? Am. J. Surg. 2015, 213, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.F.; Arora, V.M.; Rasinski, K.A.; Curlin, F.A.; Yoon, J.D. The prevalence of medical student mistreatment and its association with burnout. Acad Med. 2014, 89, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | General | Public | Private | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | <0.001 * | ||||||

| Female | 547 | 65.8% | 62 | 50.8% | 485 | 68.4% | |

| Male | 284 | 34.2% | 60 | 49.2% | 224 | 31.6% | |

| Age (years old) | 0.471 | ||||||

| 17 to 20 | 208 | 25.0% | 35 | 28.7% | 173 | 24.4% | |

| 21 to 24 | 393 | 47.3% | 58 | 47.5% | 335 | 47.2% | |

| 25 to 29 | 189 | 22.8% | 26 | 21.3% | 163 | 23.0% | |

| ≥30 | 41 | 4.9% | 3 | 2.5% | 38 | 5.4% | |

| Skin color/ethnicity | 0.021 * | ||||||

| White | 710 | 85.5% | 97 | 79.5% | 613 | 86.5% | |

| Brown | 74 | 8.9% | 16 | 13.1% | 58 | 8.2% | |

| Yellow | 35 | 4.2% | 8 | 6.6% | 27 | 3.8% | |

| Black | 11 | 1.3% | 0 | 0.00% | 11 | 1.5% | |

| Other | 1 | 0.1% | 1 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% | |

| Who do you live with | <0.001 * | ||||||

| Alone | 380 | 45.7% | 22 | 18.0% | 358 | 50.5% | |

| With parentes | 237 | 28.5% | 82 | 67.2% | 155 | 21.9% | |

| With another family member | 85 | 10.3% | 6 | 4.9% | 79 | 11.1% | |

| With friends | 82 | 9.9% | 7 | 5.8% | 75 | 10.6% | |

| With partner | 41 | 4.9% | 5 | 4.1% | 36 | 5.1% | |

| Another option | 6 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 6 | 0.8% | |

| Relationship status | 0.378 | ||||||

| Single | 428 | 51.5% | 59 | 48.4% | 369 | 52.0% | |

| Dating without living together | 346 | 41.6% | 57 | 46.7% | 289 | 40.8% | |

| Married or living together | 57 | 6.9% | 6 | 4.9% | 51 | 7.2% | |

| Religion | 0.009 * | ||||||

| Catholic | 469 | 56.5% | 67 | 54.9% | 402 | 56.7% | |

| Evangelical | 128 | 15.4% | 20 | 16.4% | 108 | 15.2% | |

| Atheist/Agnostic | 107 | 12.9% | 26 | 21.3% | 81 | 11.4% | |

| Spiritist | 66 | 7.9% | 5 | 4.1% | 61 | 8.6% | |

| Other | 61 | 7.3% | 4 | 3.3% | 57 | 8.1% | |

| Year of the course | 0.493 | ||||||

| 1st | 132 | 15.9% | 17 | 13.9% | 115 | 16.2% | |

| 2nd | 188 | 22.6% | 29 | 23.8% | 159 | 22.4% | |

| 3rd | 157 | 18.9% | 21 | 17.2% | 136 | 19.2% | |

| 4th | 132 | 15.9% | 18 | 14.8% | 114 | 16.1% | |

| 5th | 123 | 14.8% | 16 | 13.1% | 107 | 15.1% | |

| 6th | 99 | 11.9% | 21 | 17.2% | 78 | 11.0% | |

| Are you satisfied with your professional choice? | 0.847 | ||||||

| No | 4 | 0.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 0.6% | |

| Not sure yet | 62 | 7.5% | 10 | 8.2% | 52 | 7.3% | |

| Yes | 765 | 92.0% | 112 | 91.8% | 653 | 92.1% | |

| Have you ever thought about dropping out the course? | 0.636 | ||||||

| No | 574 | 69.1% | 87 | 71.3% | 487 | 68.7% | |

| Yes | 257 | 30.9% | 35 | 28.7% | 222 | 31.3% | |

| Variable | General | Public | Private | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Type of mistreatment/academic violence * | 0.034 * | ||||||

| Verbal—humiliation, depreciation or swearing | 254 | 66.3% | 53 | 72.6% | 201 | 64.6% | |

| Psychological—negative comments about their future career | 235 | 61.4% | 36 | 49.3% | 199 | 64.0% | |

| Psychological—threat of harming grades/evaluations | 192 | 50.1% | 35 | 47.9% | 157 | 50.5% | |

| Verbal—scream, shout | 116 | 30.3% | 28 | 38.4% | 88 | 28.3% | |

| Psychological—tasks with punitive purpose | 85 | 22.2% | 22 | 30.1% | 63 | 20.3% | |

| Psychological—threat of disapproval | 61 | 15.9% | 18 | 24.7% | 43 | 13.8% | |

| Sexual—situations of harassment | 54 | 14.1% | 9 | 12.3% | 45 | 14.5% | |

| Psychological—misappropriation of credit | 44 | 11.5% | 8 | 11.0% | 36 | 11.6% | |

| Psychological—ethnic or religious prejudice | 37 | 9.7% | 11 | 15.1% | 26 | 8.4% | |

| Sexual—sexual discrimination | 21 | 5.5% | 2 | 2.7% | 19 | 6.1% | |

| Psychological—threat of physical aggression | 2 | 0.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 2 | 0.7% | |

| Physical aggression | 2 | 0.5% | 1 | 1.4% | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Frequency of mistreatment occurrence | 0.079 | ||||||

| Rarely (1/2 times) | 200 | 52.2% | 29 | 40.3% | 171 | 55.0% | |

| Sometimes (3/4 times) | 140 | 36.6% | 33 | 45.8% | 107 | 34.4% | |

| Often (5 or more times) | 43 | 11.2% | 10 | 13.9% | 33 | 10.6% | |

| Aggressor * | 0.13 | ||||||

| Faculty member | 328 | 85.6% | 64 | 87.7% | 264 | 84.9% | |

| Preceptor | 105 | 27.4% | 12 | 16.4% | 93 | 29.9% | |

| Doctor of the service where the student interns | 89 | 23.2% | 23 | 31.5% | 66 | 21.2% | |

| Nurse | 61 | 15.9% | 9 | 12.3% | 52 | 16.7% | |

| Resident | 62 | 16.2% | 11 | 15.1% | 51 | 16.4% | |

| Patient/family member/companion | 32 | 8.4% | 6 | 8.2% | 26 | 8.4% | |

| Another health professional | 19 | 5.0% | 2 | 2.7% | 17 | 5.5% | |

| Colleagues | 13 | 3.4% | 4 | 5.5% | 9 | 2.9% | |

| Other | 10 | 2.6% | 1 | 1.4% | 9 | 2.9% | |

| Variable | General | Public | Private | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Severity of the aggressor’s attitude | 0.584 | ||||||

| It didn’t affect me | 20 | 5.2% | 5 | 6.9% | 15 | 4.8% | |

| Affected a little | 164 | 42.8% | 33 | 45.9% | 131 | 42.1% | |

| Affected a lot | 199 | 52.0% | 34 | 47.2% | 165 | 53.1% | |

| Effects caused *,1 | 0.622 | ||||||

| I felt diminished and depressed | 282 | 77.7% | 53 | 79.1% | 229 | 77.4% | |

| It created a feeling of contempt for the faculty and hindered the later relationship with him | 264 | 72.7% | 51 | 76.1% | 213 | 72.0% | |

| It caused me intense stress | 252 | 69.4% | 46 | 68.7% | 206 | 69.6% | |

| It created a poor learning environment, reflecting impairment in academic performance | 186 | 51.2% | 36 | 53.7% | 150 | 50.7% | |

| It made me seek for professional help (psychiatrist or psychologist) | 101 | 27.8% | 13 | 19.4% | 88 | 29.7% | |

| It made me study harder and made me stronger to face the typical situations of the medical profession | 73 | 20.1% | 17 | 25.4% | 56 | 18.9% | |

| It made me increase my consumption of alcoholic beverages and/or other legal drugs | 30 | 8.3% | 4 | 6.0% | 26 | 8.8% | |

| Variable | General | Public | Private | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Reported the fact to someone in the coordination of the course or direction of the Health Sciences Center | 0.116 | ||||||

| No | 347 | 90.6% | 69 | 95.8% | 278 | 89.4% | |

| Yes | 36 | 9.4% | 3 | 4.2% | 33 | 10.6% | |

| Why did you not report? *,1 | 0.477 | ||||||

| For thinking that nothing would be done about it. | 250 | 72.1% | 53 | 76.8% | 197 | 70.9% | |

| For fear of reprisal (related to grades and evaluations) | 163 | 47.0% | 37 | 53.6% | 126 | 45.3% | |

| For thinking that I could handle/resolve the situation by myself. | 117 | 33.7% | 22 | 31.9% | 95 | 34.2% | |

| Was in doubt if the fact really represented an inappropriate attitude on the part of the perpetuator or if it was part of the normal learning proccess of the course. | 96 | 27.7% | 16 | 23.2% | 80 | 28.8% | |

| What did you think of the outcome of the complaint? 2 | 0.545 | ||||||

| I felt dissatisfied; nothing was done in an attempt to help me | 26 | 72.2% | 3 | 100.0% | 23 | 69.7% | |

| I felt satisfied with the attitude of the coordination/direction | 10 | 27.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 30.3% | |

| Variable | OR (Adjusted) | CI (95%) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institution | |||

| Public | 1 | - | - |

| Private | 0.45 | 0.29–0.68 | <0.001 * |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1 | - | - |

| Male | 0.5 | 0.36–0.69 | <0.001 * |

| Age (years old) | |||

| 17 to 20 | 1 | - | - |

| 21 to 24 | 1.25 | 0.83–1.9 | 0.293 |

| 25 to 29 | 1.76 | 1.04–3 | 0.035 * |

| ≥30 | 1.27 | 0.57–2.8 | 0.554 |

| Relationship status | |||

| Single | 1 | - | - |

| Dating without living together | 1.22 | 0.89–1.66 | 0.214 |

| Married or living together | 0.93 | 0.5–1.72 | 0.807 |

| Year of the course | |||

| 6th | 1 | - | - |

| 5th | 1.55 | 0.86–2.81 | 0.148 |

| 4th | 0.67 | 0.38–1.18 | 0.166 |

| 3rd | 0.47 | 0.26–0.82 | 0.009 * |

| 2nd | 0.36 | 0.2–0.65 | <0.001 * |

| 1st | 0.24 | 0.12–0.45 | <0.001 * |

| Have you ever thought about dropping out the course? | |||

| No | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 1.5 | 1.09–2.07 | 0.014 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barbanti, P.C.M.; Oliveira, S.R.L.d.; de Medeiros, A.E.; Bitencourt, M.R.; Victorino, S.V.Z.; Bitencourt, M.R.; Alarcão, A.C.J.; Egger, P.A.; Pelloso, F.C.; Borghesan, D.H.P.; et al. Prevalence and Impact of Academic Violence in Medical Education. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811519

Barbanti PCM, Oliveira SRLd, de Medeiros AE, Bitencourt MR, Victorino SVZ, Bitencourt MR, Alarcão ACJ, Egger PA, Pelloso FC, Borghesan DHP, et al. Prevalence and Impact of Academic Violence in Medical Education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811519

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarbanti, Patricia Costa Mincoff, Sérgio Ricardo Lopes de Oliveira, Aline Edlaine de Medeiros, Mariá Românio Bitencourt, Silvia Veridiana Zamparoni Victorino, Marcos Rogério Bitencourt, Ana Carolina Jacinto Alarcão, Paulo Acácio Egger, Fernando Castilho Pelloso, Deise Helena Pelloso Borghesan, and et al. 2022. "Prevalence and Impact of Academic Violence in Medical Education" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811519

APA StyleBarbanti, P. C. M., Oliveira, S. R. L. d., de Medeiros, A. E., Bitencourt, M. R., Victorino, S. V. Z., Bitencourt, M. R., Alarcão, A. C. J., Egger, P. A., Pelloso, F. C., Borghesan, D. H. P., de Souza, M. P., Marques, V. D., Pelloso, S. M., & Carvalho, M. D. d. B. (2022). Prevalence and Impact of Academic Violence in Medical Education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811519