Periodontal Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Data Extraction

- -

- For PubMed: (psoriasis[MeSH Terms]) AND (periodontal disease[MeSH Terms]);

- -

- For Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY INDEXTERMS (psoriasis AND “periodontal disease”);

- -

- For Web of Science: TS = (psoriasis AND periodontal disease).

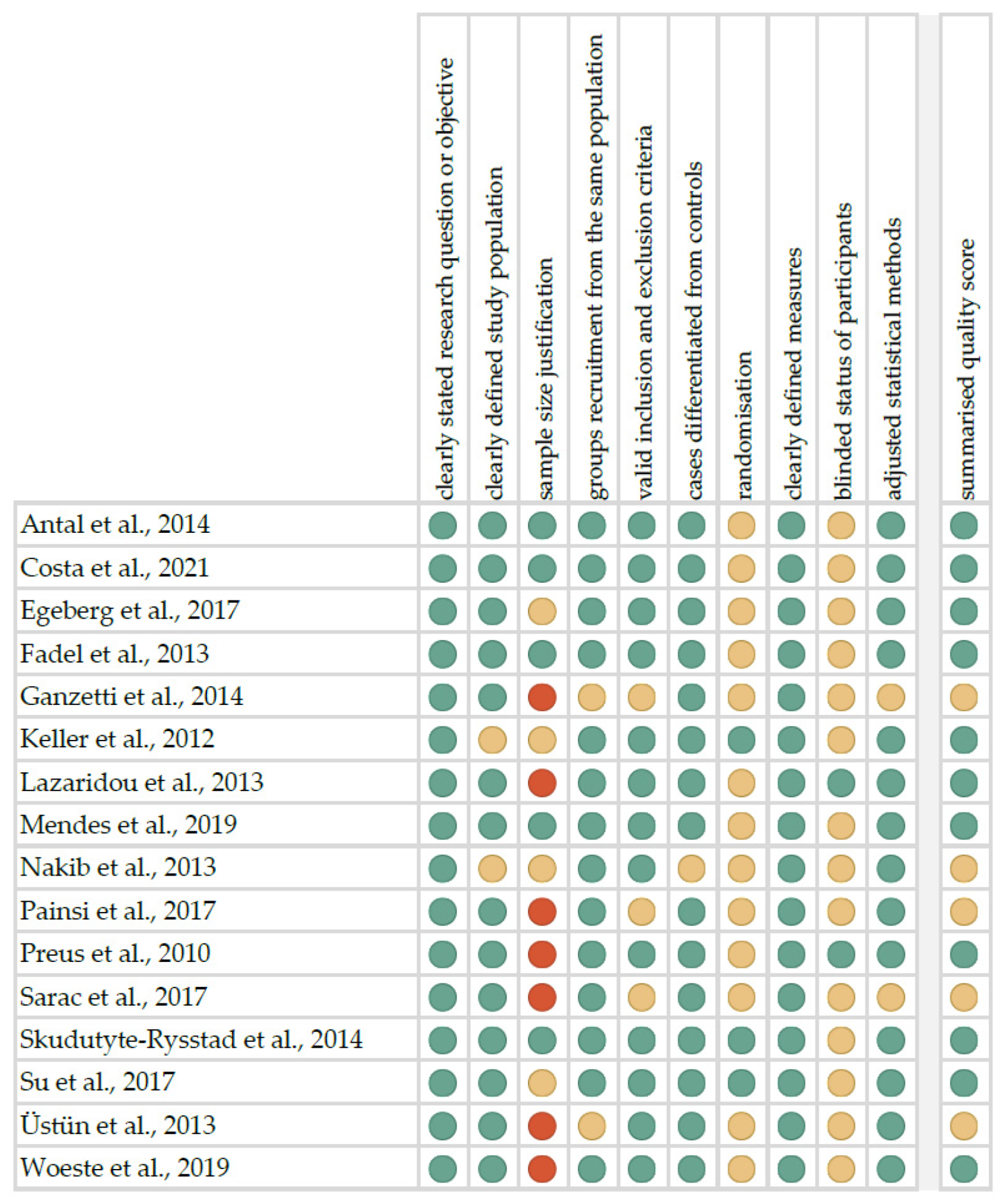

2.2. Quality Assessment and Critical Appraisal for the Systematic Review of Included Studies

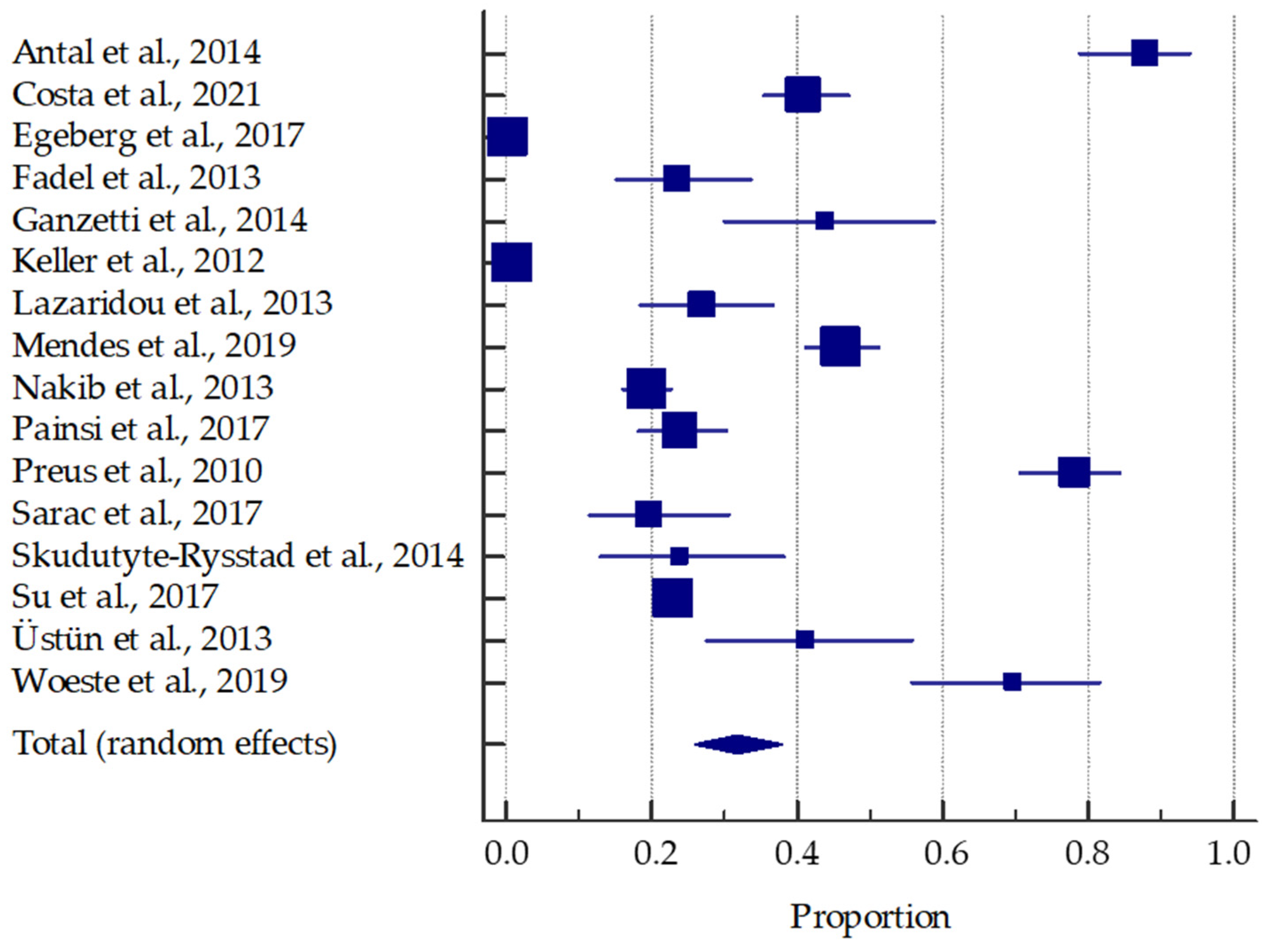

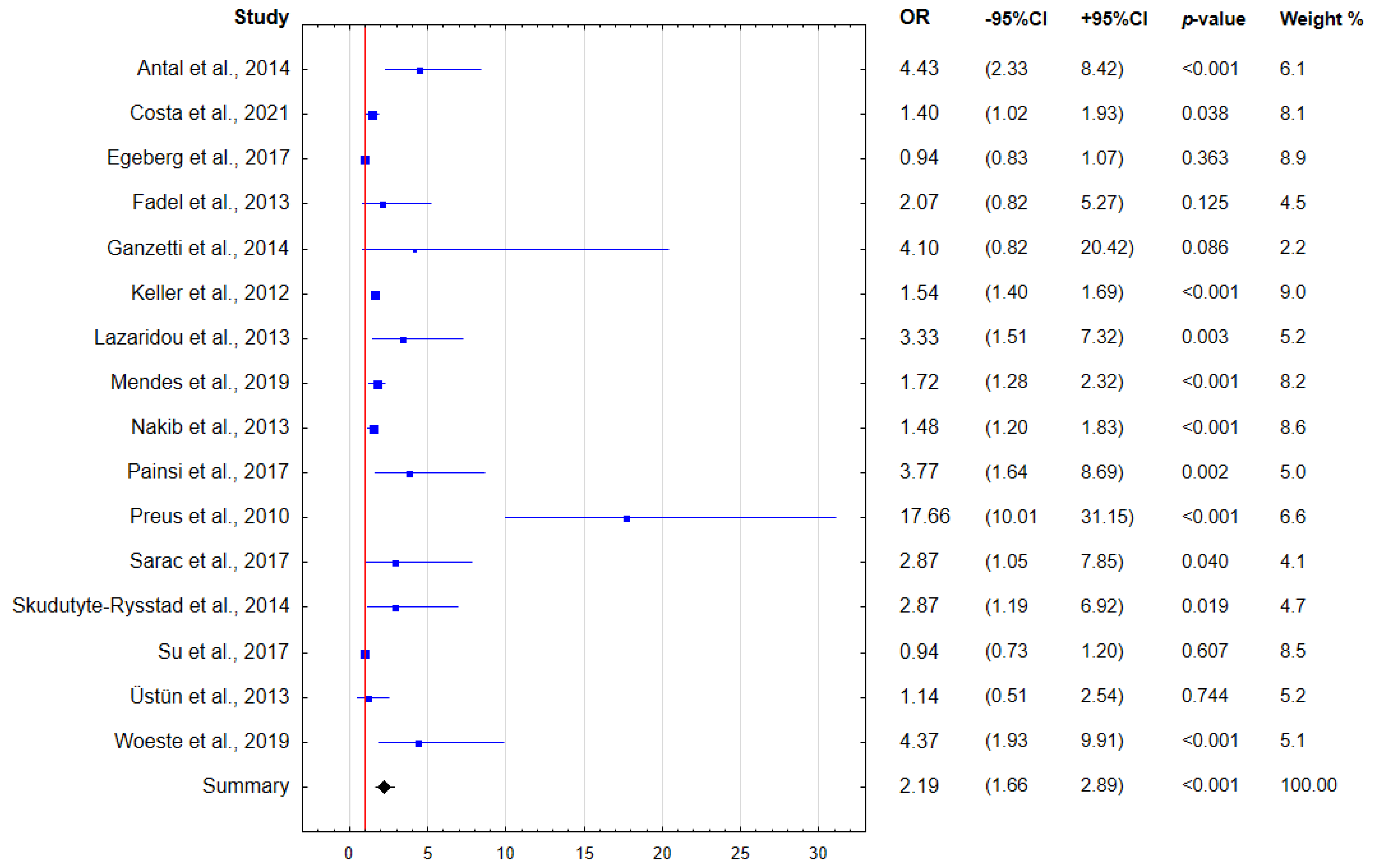

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Campanati, A.; Marani, A.; Martina, E.; Diotallevi, F.; Radi, G.; Offidani, A. Psoriasis as an Immune-Mediated and Inflammatory Systemic Disease: From Pathophysiology to Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korman, N.J. Management of Psoriasis as a Systemic Disease: What Is the Evidence? Br. J. Dermatol. 2020, 182, 840–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrowietz, U.; Reich, K. Psoriasis-New Insights into Pathogenesis and Treatment. Dtsch. Arzteblatt Int. 2009, 106, 11–18, quiz 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, R.; Symmons, D.P.M.; Griffiths, C.E.M.; Ashcroft, D.M. Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team Global Epidemiology of Psoriasis: A Systematic Review of Incidence and Prevalence. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamiya, K.; Kishimoto, M.; Sugai, J.; Komine, M.; Ohtsuki, M. Risk Factors for the Development of Psoriasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, W.A.; Gottlieb, A.B.; Mease, P. Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: Clinical Features and Disease Mechanisms. Clin. Dermatol. 2006, 24, 438–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, I.M.; Ellervik, C.; Yazdanyar, S.; Jemec, G.B.E. Meta-Analysis of Psoriasis, Cardiovascular Disease, and Associated Risk Factors. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013, 69, 1014–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Chi, C.-C. Association of Psoriasis With Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018, 154, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Chugh, S.; Bansal, S. General Measures and Quality of Life Issues in Psoriasis. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2016, 7, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhosle, M.J.; Kulkarni, A.; Feldman, S.R.; Balkrishnan, R. Quality of Life in Patients with Psoriasis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2006, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boehncke, W.-H.; Schön, M.P. Psoriasis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2015, 386, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.E.M.; Armstrong, A.W.; Gudjonsson, J.E.; Barker, J.N.W.N. Psoriasis. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2021, 397, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, M.; Osmola-Mańkowska, A.; Ślebioda, Z.; Adamski, Z.; Dorocka-Bobkowska, B. Oral Mucosal Lesions in Psoriatic Patients Based on Disease Severity and Treatment Approach. J. Oral Pathol. Med. Off. Publ. Int. Assoc. Oral Pathol. Am. Acad. Oral Pathol. 2020, 49, 822–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinane, D.F.; Stathopoulou, P.G.; Papapanou, P.N. Periodontal Diseases. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primer 2017, 3, 17038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Highfield, J. Diagnosis and Classification of Periodontal Disease. Aust. Dent. J. 2009, 54 (Suppl. S1), S11–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.A. Prevalence of Periodontal Disease, Its Association with Systemic Diseases and Prevention. Int. J. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Rapone, B.; Ferrara, E.; Santacroce, L.; Topi, S.; Gnoni, A.; Dipalma, G.; Mancini, A.; Di Domenico, M.; Tartaglia, G.M.; Scarano, A.; et al. The Gaseous Ozone Therapy as a Promising Antiseptic Adjuvant of Periodontal Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, T.; Dieterle, M.P.; Tomakidi, P. Molecular Research on Oral Diseases and Related Biomaterials: A Journey from Oral Cell Models to Advanced Regenerative Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkowski, M.; Nijakowski, K.; Kaczmarek, M.; Surdacka, A. The Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Technique in Periodontal Diagnostics: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genco, R.J.; Borgnakke, W.S. Risk Factors for Periodontal Disease. Periodontol. 2000 2013, 62, 59–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyke, T.E.; Sheilesh, D. Risk Factors for Periodontitis. J. Int. Acad. Periodontol. 2005, 7, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bui, F.Q.; Almeida-da-Silva, C.L.C.; Huynh, B.; Trinh, A.; Liu, J.; Woodward, J.; Asadi, H.; Ojcius, D.M. Association between Periodontal Pathogens and Systemic Disease. Biomed. J. 2019, 42, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arigbede, A.O.; Babatope, B.O.; Bamidele, M.K. Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases: A Literature Review. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2012, 16, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijakowski, K.; Gruszczyński, D.; Surdacka, A. Oral Health Status in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liccardo, D.; Cannavo, A.; Spagnuolo, G.; Ferrara, N.; Cittadini, A.; Rengo, C.; Rengo, G. Periodontal Disease: A Risk Factor for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendon, A.; Schäkel, K. Psoriasis Pathogenesis and Treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Raman, A.; Pradeep, A.R. Association of Chronic Periodontitis and Psoriasis: Periodontal Status with Severity of Psoriasis. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijakowski, K.; Ortarzewska, M.; Morawska, A.; Brożek, A.; Nowicki, M.; Formanowicz, D.; Surdacka, A. Bruxism Influence on Volume and Interleukin-1β Concentration of Gingival Crevicular Fluid: A Preliminary Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenobia, C.; Hajishengallis, G. Basic Biology and Role of Interleukin-17 in Immunity and Inflammation. Periodontol. 2000 2015, 69, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christophers, E. Periodontitis and Risk of Psoriasis: Another Comorbidity. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2017, 31, 757–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, L.J.; Garzón, H.; Arboleda, S.; Rodríguez, A. Oral Dysbiosis and Autoimmunity: From Local Periodontal Responses to an Imbalanced Systemic Immunity. A Review. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 591255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moen, K.; Brun, J.G.; Valen, M.; Skartveit, L.; Eribe, E.K.R.; Olsen, I.; Jonsson, R. Synovial Inflammation in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis and Psoriatic Arthritis Facilitates Trapping of a Variety of Oral Bacterial DNAs. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2006, 24, 656–663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Preus, H.R.; Khanifam, P.; Kolltveit, K.; Mørk, C.; Gjermo, P. Periodontitis in Psoriasis Patients. A Blinded, Case-Controlled Study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2010, 68, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadel, H.T.; Flytström, I.; Calander, A.-M.; Bergbrant, I.-M.; Heijl, L.; Birkhed, D. Profiles of Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease in Individuals With or Without Psoriasis. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 477–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egeberg, A.; Mallbris, L.; Gislason, G.; Hansen, P.R.; Mrowietz, U. Risk of Periodontitis in Patients with Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2017, 31, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olejnik, M.; Adamski, Z.; Osmola-Mankowska, A.; Nijakowski, K.; Dorocka-Bobkowska, B. Oral Health Status and Dental Treatment Needs of Psoriatic Patients with Different Therapy Regimes. Aust. Dent. J. 2021, 66, S42–S47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Study Quality Assessment Tools|NHLBI, NIH. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- OCEBM Levels of Evidence. Available online: https://www.cebm.net/2016/05/ocebm-levels-of-evidence/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Antal, M.; Braunitzer, G.; Mattheos, N.; Gyulai, R.; Nagy, K. Smoking as a Permissive Factor of Periodontal Disease in Psoriasis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e92333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.A.; Cota, L.O.M.; Mendes, V.S.; Oliveira, A.M.S.D.; Cyrino, R.M.; Costa, F.O. Periodontitis and the Impact of Oral Health on the Quality of Life of Psoriatic Individuals: A Case-Control Study. Clin. ORAL Investig. 2021, 25, 2827–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganzetti, G.; Campanati, A.; Santarelli, A.; Pozzi, V.; Molinelli, E.; Minnetti, I.; Brisigotti, V.; Procaccini, M.; Emanuelli, M.; Offidani, A. Periodontal Disease: An Oral Manifestation of Psoriasis or an Occasional Finding? Drug Dev. Res. 2014, 75 (Suppl. S1), S46–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.J.; Lin, H.-C. The Effects of Chronic Periodontitis and Its Treatment on the Subsequent Risk of Psoriasis. Br. J. Dermatol. 2012, 167, 1338–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazaridou, E.; Tsikrikoni, A.; Fotiadou, C.; Kyrmanidou, E.; Vakirlis, E.; Giannopoulou, C.; Apalla, Z.; Ioannides, D. Association of Chronic Plaque Psoriasis and Severe Periodontitis: A Hospital Based Case-Control Study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2013, 27, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, V.S.; Cota, L.O.M.; Costa, A.A.; Oliveira, A.M.S.D.; Costa, F.O. Periodontitis as Another Comorbidity Associated with Psoriasis: A Case-control Study. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakib, S.; Han, J.; Li, T.; Joshipura, K.; Qureshi, A.A. Periodontal Disease and Risk of Psoriasis among Nurses in the United States. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2013, 71, 1423–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Painsi, C.; Hirtenfelder, A.; Lange-Asschenfeldt, B.; Quehenberger, F.; Wolf, P. The Prevalence of Periodontitis Is Increased in Psoriasis and Linked to Its Inverse Subtype. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2017, 30, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarac, G.; Kapicioglu, Y.; Cayli, S.; Altas, A.; Yologlu, S. Is the Periodontal Status a Risk Factor for the Development of Psoriasis? Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2017, 20, 474–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skudutyte-Rysstad, R.; Slevolden, E.M.; Hansen, B.F.; Sandvik, L.; Preus, H.R. Association between Moderate to Severe Psoriasis and Periodontitis in a Scandinavian Population. BMC Oral Health 2014, 14, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.-Y.; Huang, J.-Y.; Hu, C.-J.; Yu, H.-C.; Chang, Y.-C. Increased Risk of Periodontitis in Patients with Psoriatic Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. PEERJ 2017, 5, e4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, K.; Sezer, U.; Kısacık, B.; Şenyurt, S.Z.; Özdemir, E.Ç.; Kimyon, G.; Pehlivan, Y.; Erciyas, K.; Onat, A.M. Periodontal Disease in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. Inflammation 2013, 36, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woeste, S.; Graetz, C.; Gerdes, S.; Mrowietz, U. Oral Health in Patients with Psoriasis-A Prospective Study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, M.S.; Greenwell, H.; Kornman, K.S. Staging and Grading of Periodontitis: Framework and Proposal of a New Classification and Case Definition. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45 (Suppl. S20), S149–S161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Parameter | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Patients with psoriasis—aged from 0 to 99 years, both genders | Patients with other dermatological diseases |

| Intervention/exposure | Periodontal disease | |

| Comparison | Healthy subjects | |

| Outcomes | Determined indices of periodontal status and/or prevalence of periodontitis | Determined only other indices of oral-health status |

| Study design | Case–control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies | Literature reviews, case reports, expert opinion, letters to the editor, conference reports, |

| published after 2000 | not published in English |

| Author, Year, Setting | Participants (F/M; Age) | Controls (F/M; Age) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Psoriasis Severity | Clinical Criteria for Periodontal Disease | Determined Periodontal Indices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antal et al., 2014, Hungary [40] | 82 (45/37); 50.9 ± 13.4 | 89 (44/45); 50.3 ± 13.7 | Patients diagnosed with psoriasis (defined as ICD-10 L40.0–L40.9) by a dermatologist | Obesity (BMI ≥ 30); excessive alcohol consumption; drug abuse; diabetes mellitus; oestrogen deficiency; diseases causing neutropenia; local or systemic inflammatory conditions (other than psoriasis) | NR | Early periodontitis: CAL ≥ 1 mm in ≥2 teeth (CPITN 2); moderate periodontitis: 3 sites with CAL ≥ 4 mm, and at least 2 sites with PPD ≥ 3 mm (CPITN 3); severe periodontitis: CAL ≥ 6 mm in ≥ 2 teeth, and PPD ≥ 5 mm in ≥1 site (CPITN 4) | BOP; CAL; PPD; number of missing teeth; PlI |

| Costa et al., 2021, Brazil [41] | 295 (181/114); 49.41 ± 4.17 | 359 (225/134); 47.47 ± 5.06 | Patients between 18 and 65 years of age; presence of at least 12 teeth; absence of contraindications for periodontal clinical examination | Antibiotic therapy or periodontal treatment over the 3 months prior to study entry | Mild psoriasis: 80; moderate psoriasis: 117; severe psoriasis: 98 | Moderate, severe, and advanced periodontitis (Stages II, III, and IV, respectively), according to the criteria defined by Tonetti et al. [53] | CAL; number of teeth; PCR; BOP; PPD |

| Egeberg et al., 2017, Denmark [35] | 67,626 (34,861/32,765); mean: 44.0 | 5,402,799 (2,736,495/2,666,304); 40.8 ± 19.7 | Danish individuals aged ≥ 18 years | Prevalent psoriasis or periodontitis at baseline | Mild psoriasis: 54,210; severe psoriasis: 6988; psoriatic arthritis: 6428 | NR | NR |

| Fadel et al., 2013, Sweden [34] | 89 (43/46); 59 ± 10 | 54 (33/21); 60 ± 11 | Patients over 40 years of age who have been diagnosed with psoriasis for ≥ 10 years | Unclear psoriasis diagnosis; the absence of present signs of psoriasis; lack of interest in completing the study | Mild to moderate psoriasis: 86; severe psoriasis: 3 | Mild periodontitis: radiographic alveolar-bone level from 2 to 3.5 mm from CEJ and BOP; moderate periodontitis: radiographic alveolar-bone level from 4 to 5.5 mm from CEJ and BOP; severe periodontitis: radiographic alveolar-bone level of ≥ 6 mm from CEJ and BOP | Radiographic alveolar-bone level; PPD; BOP; number of teeth |

| Ganzetti et al., 2014, Italy [42] | 50 (22/28); 44.7 ± 11.5 | 45 (gender and age-matched) | Patients who were diagnosed with psoriasis by a trained dermatologist | NR | Moderate or severe psoriasis (PASI ≥ 10) | Slight periodontitis: CAL 1–2 mm; moderate periodontitis: CAL 3–4 mm; severe periodontitis: CAL ≥ 5 mm | CAL |

| Keller et al., 2012, Taiwan [43] | 1788; NR | 228,942; NR | Patients ≥ 18 years who received a first-time diagnosis of chronic periodontitis between 1 January 2001 and 31 December 2004 | History of psoriasis prior to index date | NR | NR | NR |

| Lazaridou et al., 2013, Greece [44] | 100 (57/43); 57.2 ± 5.3 | 100 (gender and age-matched) | Patients with biopsy-confirmed CPP with a duration of the disease of at least 6 months | Systemic therapy for CPP (cyclosporine, methotrexate, biologic agents) at presenting and 1 year before; systemic therapy for comorbidities suggesting autoimmune background (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, any rheumatologic condition; any other type of psoriasis; visible lesions on sites uncovered by clothing) | Mild psoriasis: 63; moderate psoriasis: 22; severe psoriasis: 15 | Score at least 3 points according to community periodontal index (CPI) | PPD |

| Mendes et al., 2019, Brazil [45] | 397 (238/159); 46.03 ± 8.34 | 359 (225/134); 47.47 ± 5.06 | Patients between 18 and 65 years of age; presence of at least 12 teeth; absence of contraindications for periodontal clinical examination | Antibiotic therapy or periodontal therapy over the last 3 months; continuous use of anti-inflammatory drugs; the third molars; impossibility of determining the cementum-enamel junction; teeth with severe gingival morphology changes preventing periodontal probing; teeth with extensive carious lesions; teeth with iatrogenic restorative procedures preventing the completion of the exam; excessive presence of calculus | Mild psoriasis: 99; moderate psoriasis: 177; severe psoriasis: 121 | Mild periodontitis: ≥2 interproximal sites with CAL ≥ 3 mm and ≥2 interproximal sites with PPD ≥ 4 mm (not on the same tooth), or 1 site with PPD ≥ 5 mm; moderate periodontitis: two or more interproximal sites with CAL ≥ 4 mm (not on the same tooth), or two or more interproximal sites with PPD ≥ 5 mm, also not on the same tooth; severe periodontitis: two or more interproximal sites with CAL ≥ 6 mm (not on the same tooth), and one or more interproximal site(s) with PPD ≥ 5 mm | CAL; number of teeth; PCR; BOP; PPD |

| Nakib et al., 2013, USA [46] | 554; NR | 80,824; NR | Self-reported history of periodontal bone loss in 1998 | Patients with psoriasis at the time when dental measures were obtained | NR | Mild, moderate, or severe periodontal bone loss | Periodontal-bone loss; number of natural teeth and tooth loss |

| Painsi et al., 2017, Austria [47] | 209 (81/128); median: 51 (range: 13–85) | 91 (54/37); median: 40 (range: 7–78), with chronic spontaneous urticaria | Patients who underwent inflammatory focus screening, including a dental checkup (DCU), between January 2007 and February 2016 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Preus et al., 2010, Norway [33] | 155 (88/67); mean: 51 | 155 (gender and age-matched) | Complete response to the questionnaire; provided bite-wing X-rays from patients’ dentists | Lack of response from the patients; lack of written consent or insufficient answers; lack of name or telephone no. of dentist; lack of response from dentist in time; insufficient quality of X-rays | NR | NR | Number of missing teeth; radiographic alveolar-bone level |

| Sarac et al., 2017, Turkey [48] | 76 (45/31); 34.43 ± 14.48 | 76 (52/24); 30.80 ± 11.19 | Patients with all the clinical types of psoriasis | NR | PASI 0–5: 35; PASI 5–15: 30; PASI > 15: 11 | CPI scores: 0: no periodontal disease; 1: gingival bleeding; 2: calculus detected while probing; 3: PPD 4–5 mm; 4: PPD 6 mm and above | PPD |

| Skudutyte-Rysstad et al., 2014, Norway [49] | 50 (12/38); 44.4 ± 10.2 | 121 (60/61); 48.6 ± 9.4 | Patients between 18 and 65 years of age with moderate to severe psoriasis for >5 years | Refusal to participate; familiar hypercholesterolemia; concomitant inflammatory diseases; autoimmune disorders; malignancies; pregnancy; edentulism | Moderate or severe psoriasis (PASI ≥ 10) | Moderate periodontitis: ≥2 interproximal sites with CAL ≥ 4 mm (not on same tooth), or ≥2 interproximal sites with PPD ≥ 5 mm (not on same tooth); severe periodontitis: ≥2 interproximal sites with CAL ≥ 6 mm (not on same tooth), and ≥1 interproximal site with PPD ≥ 5 mm | PPD; CAL; number of missing teeth; PCR; BOP |

| Su et al., 2017, Taiwan [50] | 3487 (1374/2113); 45.28 ± 19.52 | 13,948 (5391/8557); 45.43 ± 19.62 | Patients newly diagnosed with psoriasis from 2003 to 2012 | Psoriatic-disease patients without any treatment, including the use of biologic drugs, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, psoralens, retinoids, methotrexate, or phototherapeutics, within a one-year | NR | NR | NR |

| Üstün et al., 2013, Turkey [51] | 51 (24/27); 41.73 ± 11.27 | 50 (26/24); 37.90 ± 11.16 | Patients who fulfilled the CASPAR classification criteria for psoriatic arthritis | history of periodontal therapy; use of antibiotics during the 3 months prior to the examination; history of other systemic conditions or diseases | NR | The criteria for chronic periodontitis were at least four teeth with PPD ≥ 5 mm, and with CAL ≥ 2 mm at the same time | PPD; CAL; PlI; GI |

| Woeste et al., 2019, Germany [52] | 100 (41/59); 47.4 ± 14.7 | 101 (58/43); 46.9 ± 16.8 | Psoriasis patients presenting at the outpatient service of a specialised psoriasis centre | Inflammatory or autoimmune skin disease in addition to psoriasis; another chronic inflammatory disease; autoimmune disease; treatment with immunosuppressive drugs, if used for a disease other than psoriasis and psoriasis arthritis; cancer; enhanced risk of endocarditis | Mild or moderate/severe | Periodontally healthy: CPI code of 1–2; presence of gingival or periodontal pockets: CPI code of 3–4 | BOP; PPD |

| Study | Clinical Indices | Psoriasis | Controls | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Costa et al., 2021 [41] | BOP, % | 46.1 ± 49.8 | 39.9 ± 49.0 | <0.001 * |

| CAL, mm | 3.79 ± 1.22 | 3.40 ± 1.20 | <0.001 * | |

| PPD, mm | 3.33 ± 1.26 | 2.85 ± 1.27 | <0.001 * | |

| PCR, % | 41.8 ± 10.5 | 39.4 ± 11.1 | <0.002 * | |

| Number of teeth | 25.4 ± 2.6 | 25.7 ± 2.3 | 0.211 | |

| Fadel et al., 2013 [34] | BOP, no. of sites | 43 ± 23 | 41 ± 25 | 0.647 |

| PPD ≥ 5 mm, no. of sites | 6 ± 6 | 4 ± 5 | 0.100 | |

| Alveolar bone level, mm | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 0.030 * | |

| Number of teeth | 24 ± 4 | 26 ± 3 | 0.015 * | |

| Mendes et al., 2019 [45] | BOP, % | 45.6 ± 17.5 | 39.3 ± 14.6 | <0.001 * |

| CAL, mm | 3.59 ± 0.92 | 3.40 ± 0.69 | 0.016 * | |

| PPD, mm | 3.12 ± 0.86 | 2.85 ± 0.58 | <0.001 * | |

| PCR, % | 41.7 ± 10.3 | 39.4 ± 11.1 | <0.001 * | |

| Number of teeth | 23.2 ± 2.9 | 24.8 ± 3.0 | 0.085 | |

| Skudutyte-Rysstad et al., 2014 [49] | BOP, % | 37 ± 18 | 24 ± 13 | <0.05 * |

| CAL ≥ 2 mm, % of sites | 6.6 ± 9.5 | 6.6 ± 8.8 | ns | |

| PPD ≥ 5 mm, % of sites | 1.5 ± 3.3 | 0.6 ± 1.9 | <0.05 * | |

| PPD ≥ 4 mm, % of sites | 3.7 ± 4.1 | 1.9 ± 3.8 | <0.05 * | |

| PCR, % | 41 ± 25 | 29 ± 20 | <0.05 * | |

| Number of missing teeth | 2.4 ± 3.9 | 1.4 ± 2.5 | <0.05 * | |

| Üstün et al., 2013 [51] | CAL, mm | 3.30 ± 1.22 | 2.83 ± 0.99 | 0.037 * |

| PPD, mm | 3.11 ± 1.14 | 2.72 ± 0.92 | 0.063 | |

| PlI | 1.50 ± 0.51 | 1.47 ± 0.64 | 0.776 | |

| GI | 1.33 ± 0.40 | 1.29 ± 0.39 | 0.543 | |

| Woeste et al., 2019 [52] | BOP, % | 41.42 ± 25.57 | 28.34 ± 20.25 | <0.011 * |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nijakowski, K.; Gruszczyński, D.; Kolasińska, J.; Kopała, D.; Surdacka, A. Periodontal Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811302

Nijakowski K, Gruszczyński D, Kolasińska J, Kopała D, Surdacka A. Periodontal Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(18):11302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811302

Chicago/Turabian StyleNijakowski, Kacper, Dawid Gruszczyński, Julia Kolasińska, Dariusz Kopała, and Anna Surdacka. 2022. "Periodontal Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 18: 11302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811302

APA StyleNijakowski, K., Gruszczyński, D., Kolasińska, J., Kopała, D., & Surdacka, A. (2022). Periodontal Disease in Patients with Psoriasis: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811302