1. Introduction

The experience of teaching at the university level is quite stimulating. It carries an enriched experience full of information and is also socially quite fascinating, but it also comes at a cost. At times, this role becomes a source of competition and thus becomes more stressful than any other job. Therefore, it can be concluded that the pursuit of a long and successful career even in academia is challenging and arduous, making faculty members vulnerable to risks of compromised well-being [

1,

2], because faculty members within their role have several other responsibilities, like undertaking research, administrative tasks, winning external grant projects, and teaching the most important. It, coupled with working extra time for other administrative or research-related jobs, with no such significant salary increases, makes it even more challenging [

3]. It is a long-ignored reality that these faculty members are at risk of compromised well-being [

4]. Further, the stress is added upon by the conflicts and ambiguity in the roles assigned to these teachers [

5], making it challenging to maintain a work-life balance [

6]. It has been evident that illness, absence, high turnover rates, early retirement, and mental issues are majorly caused by the stress these faculty members undergo [

7]. Researchers undertaking the study to understand the professional health of these faculty members have laid great emphasis upon the fact that high level of stress, lower level of stress resistance, and even lowest level of tolerance in frustrating situations is much higher in the social group of teachers in comparison to that of many other social and professional groups [

8]. Conventionally, the teachers are at the forefront of nurturing and developing students’ potential [

9], and teachers help students’ growth [

10]. Teachers must remain physically and mentally well to help students grow and reach their full potential [

11]. A great deal of literature has explained the interaction of social and health conditions of academic staff members [

12]. Part of the work is devoted to improving the quality of education through the improvement of the working conditions of teachers. More recently, studies on the creating and building of a sustainable and healthy working environment during the contractual, partial work setting [

13] and extending to the aspect of stress and struggle an employee goes through during the job [

14] seem to be the relevant ones. Faculty members teaching at such a high level also feel exhaustion [

15], stress, and depression [

16] prevail, along with low work–life balance [

4].

The manifestation of a social welfare structure depends on a network representing a definition of health, satisfaction with physical health conditions, and social interactions. Accordingly, three basic norms define the rule and law of positive emotions, which are found in the welfare system and its structure [

1]. Workers’ lives are “One of the most prominent challenges posed to the leaders these days” [

17]. With the increased and more devoted focus on the employee’s well-being by the researchers, this issue is being highlighted and has gained importance in discussions [

3]. Therefore, “Academic interest in employee welfare has also increased significantly in recent years” [

3]. Similarly, “the well-being of the workforce has emerged as a crucial component in good governance-based research” [

16]. Before understanding what well-being implies to teachers, we must define this term. Well-being refers to being tested for one’s belief about a happy and satisfying life. It has also been described as a social environment in which people understand and learn about their self-capabilities, understand and face the day-to-day pressures, their official duties, tasks and responsibilities along with being a responsible and committed member of the community” [

4]. A person’s “mental well-being” is understood to be his/her positive experience, which is primarily determined by factors of external influence [

18]. Psychological well-being can be understood by analyzing the factors such as performance, job satisfaction, and experience. Various factors can be linked to employee well-being, like physical, mental, and social [

19]. Employee well-being is essential to organizations because it reflects the organization’s life. For the well-being of the employees, organizations must be healthy and healthy organizations are well managed and organized and must have standardized efforts to enhance the psychological well-being and overall productivity of their employees by providing them practical purpose, organizational support, and equal opportunities for professional growth and better personal life [

20]. Thus, it is vital to improving the well-being of employees. However, employee welfare takes many shapes and actions according to an organization’s policies and the implementation of these policies to increase the employee’s overall well-being can improve one type of employee well-being while reducing a different kind of employee well-being. Therefore, it is crucial to see if a factor in the workplace can improve their quality of life without harming any other type of employee well-being [

1]. The spirituality of the workplace is one aspect of the workplace that can enhance many types of employee well-being. The level of spirit defines a person’s expression or spiritual knowledge at work puts at their job [

21]. Specifically, work ethic refers to a meaningful employee experience and community at work [

22]. Other related words are associated with spiritual experience in the workplace, including calling, membership [

17], and transcendence [

19]. Existing literature raises the need for workplace spirituality [

13], and that is why one of the significant aspects of spirituality and work has been described and termed as one of the most attention-seeking issues in terms of scientific research [

23].

According to the literature, workplace spirituality “tends to have a strong impact and effects on the individuals, organizations, and community’s overall well-being and prosperity” [

23]. Additionally, workplace spirituality can help these organizations that address the general health issues related to workplace spirituality that affects the employed human resource [

24]. Similarly, it suggests that spirituality improves general employee health and tends to improve the employee’s overall well-being. Other literature also shows that there is still a great deal, and this should be debated that this practice at the organizational level may improve factors like increased ethics, decreased stress, and less burnout at work [

25]. In line with this, a model of the concept was developed where the work ethic, through the mediation of the organization’s commitment to employees, is linked to the mental well-being of employees [

26]. The spiritual foundation in the office environment depends on the employee’s belief in the purpose and meaningful work [

27]. Suppose the content of the work gives people a good spiritual experience. In that case, it will lead to spiritual growth and development, empathy and feelings of happiness, motivation for work, and well-being [

1]. It has been evident in the literature that workplace spirituality is related to and consequent upon the feeling of being satisfied by passing on to individuals, groups, or organizations [

12]. The main aspects of the work ethic mentioned are internal health, purpose, and purpose in the workplace, a feeling of social togetherness, and alignment with the organization’s values [

17]. Feeling part of the community (connecting with others) is essential for spiritual growth [

1]. This important spiritual dimension in the workplace occurs at the group level, where employees meet with others who work hand in hand with each other and develop strong communication between people [

2,

28].

Workplace spirituality has four levels: meaningful work, spirituality, compassion, and alignment of values [

29]. Meaningful work can be defined as the pursuit of a higher purpose [

30]. Spirituality is defined as the transcendent experience that a person has at work [

31]. It can also be described as the level of sensible employees who get from their job [

30]. Compassion is defined as the emotional connection between employees that motivates them to help others [

32], and alignment of values can be defined as the harmony between personal beliefs and the norms of one’s work [

33]. In other words, it is the psychological connection of employees with their workplace. The scriptures show that spirituality enables a person to benefit by increasing “happiness, peace, tranquility, satisfaction in work and commitment” [

29]. Spirituality is also associated with increased creativity, honesty, and reliance on job verification between career growth and career goals [

31]. Keeping in view all the work undertaken so far, we found a dearth of research on how different dimensions of workplace spirituality in academia are linked with psychological well-being and stress levels among university teachers.

1.1. Significance and Novelty of the Research

It is necessary to highlight the practice of workplace spirituality among university teachers because there are no formal studies on whether workplace spirituality is practiced in academia and what relation it has with the mental well-being of teachers. It is essential to consider the mental well-being and stress level of university teachers because a teaching activity cannot be conceived without the direct involvement of a teacher [

33]. Even if we consider the progressing educationalists whose focus is mainly on the part and role of the learners, the role of a teacher, which is no less than that of a mentor, can never be ignored. Even for a learner, it will be impossible to groom and grow without a teacher’s direct or indirect involvement [

34,

35]. A teacher’s role is of utmost importance regarding logic, understanding, thinking, or morality. Parmar et al. [

1] highlight the fact that it is a teacher who enables a learner to put his brain at work, ask essential and relevant questions, write, and grasp the concept from the reading, work in teams, understand a common good, and ultimately link the conscious with conduct. To summarize, a teacher’s role is of great importance in facilitating the growth and grooming of society as a whole and individual, curtailing democracy and morality [

17]. Having such expectations and responsibilities, they must experience stress and psychological difficulties. The practice of workplace spirituality creates a mentally healthy environment and strengths the person’s capacity to deal with such stress. If teachers are not provided with the right workplace environment, it will be difficult for them to perform their duties properly [

36]. Therefore, it is necessary to identify whether workplace spirituality is being practiced in academia or not. Besides this, it is essential to understand how it improves the overall mental well-being of university teachers [

37,

38].

1.2. The Objectives of the Research

The literature on workplace spirituality has several limitations. Therefore, the research has several objectives, for instance, to establish the impact of workplace spirituality on university teachers’ psychological well-being. Workplace spirituality is a new dimension in global work culture, since employees’ collective needs and values shift. Therefore, spirituality at work becomes a significant factor at work [

35]. Research studies have primarily been conducted on a person’s spiritual experiences at the job instead of how the different workplace spirituality dimensions impact individuals’ work attitude and mental well-being [

17,

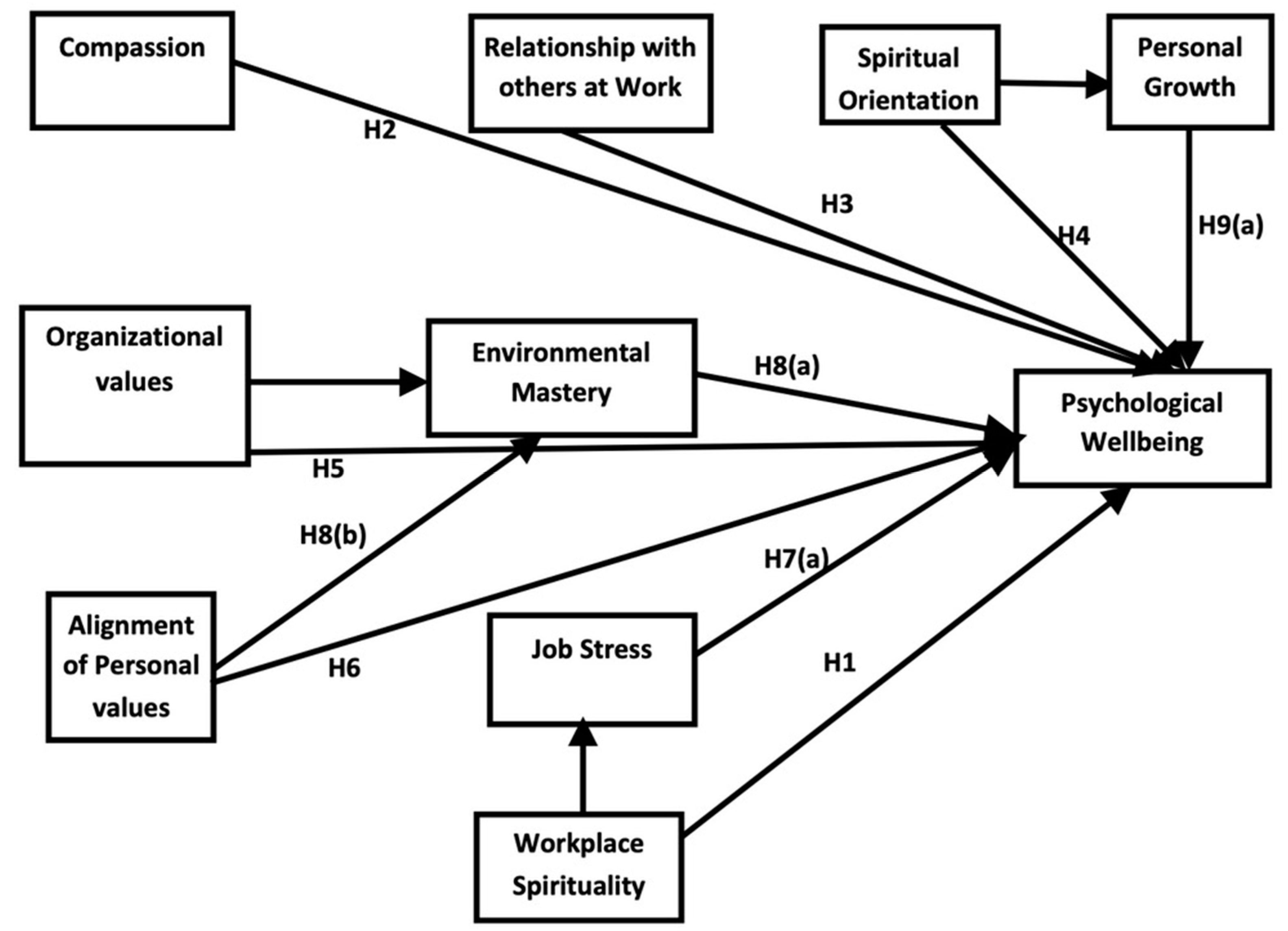

39]. The main objective of this research study is to investigate the relationship of different dimensions of workplace spirituality, e.g., compassion, relationship with others at work, spiritual orientation, organizational value, and alignment of personal value, with psychological well-being and job stress [

38,

40]. There is a gap in the literature, as primary workplace spirituality-related studies have been conducted on business employees or doctors [

17,

37] but not on teachers. Additionally, we also analyzed the impact of job stress, environmental mastery, and personal growth as mediating variables between independent variables, such as workplace spirituality, compassion, relationship with others at work, spiritual orientation, organizational value, and alignment of personal value, and psychological well-being [

34,

38].

5. Discussions

The current study aims to understand the relationship of workplace spirituality with the different dimensions of psychological well-being along with job stress, environmental mastery, and personal growth as mediating variables. The findings of a direct relationship exhibited that the independent variables, such as workplace spirituality, compassion, relationship with others at work, spiritual orientation, organizational value, and alignment of personal values, have a significant and positive relationship with psychological well-being. The findings of this research predicted a positive and robust impact of workplace spirituality on the overall psychological well-being of universities’ teachers, meaning that the higher the level of the practice of spirituality at work, the higher would be the level of psychological well-being [

6,

29,

35]. Another study found that individuals who experience high workplace spirituality also have high self-esteem and experience a higher level of psychological well-being [

9,

27]. The practice of workplace spirituality increases self-esteem, which results in higher psychological security and satisfaction, which in return enhances psychological well-being [

1,

5,

10]. Another study found that psychological well-being is predicted by workplace spirituality [

7]. In the current study, compassion significantly and positively impacts psychological well-being. The previous literature also demonstrated similar results [

11,

13,

17,

57].

Similarly, the study’s findings exhibited that spiritual orientation has a significant and positive relationship with the psychological well-being of university teachers. The previous studies also demonstrated a similar outcome [

12,

14,

15,

35]. Spiritual orientation is the attitude, belief system, and knowledge that helps individuals in deriving meaning and purpose from life and work specifically, whereas personal growth is one of the dimensions of the psychological well-being model, which includes the development of skills and potential [

16,

18,

57]. The hypothesis predicted a positive and significant relationship between the two: if the workplace has a spiritual orientation, the employees will have a higher level of psychological well-being [

23,

25]. This research was conducted with university teachers. It can be said that in academia, there is a lack of understanding of the importance of the well-being of the teachers, and there is some level of importance placed on physical well-being. For example, if a teacher is unwell physiologically, he/she can get leave, but when it comes to mental well-being, it is not recognized fully, and the understanding of the link between spiritual orientation and personal growth and their importance is not fully identified [

20,

21,

57]. These are the possible reasons that teachers’ psychological well-being is compromised, and they are not mentally fit enough to have personal growth even in the presence of high spiritual orientation at the workplace [

27,

28,

30].

The findings also predicted a positive and significant association between the alignment of personal & organizational values and the psychological well-being of university teachers. Previous literature also demonstrated consistent results [

28,

29,

31]. It can be assumed that when an employee has his values aligned, he can understand and thus control crises more effectively [

32,

33]. The study conducted on workplace spirituality and turnover intentions among doctors suggests that when organizational values are aligned with personal values, employees can maintain harmony between work and life, which lowers the chances of turnover intentions [

34,

41]. Likewise, in the present study, teachers could control their surroundings and develop mastery. However, due to low levels of workplace spirituality and a higher stress level, they could not develop mastery over their environment, as the higher stress level affected their psychological well-being [

34,

35]. The findings further exhibited the positive and significant relationship relations with others at work and psychological well-being. Previous studies show that compassion in the workplace promotes better relations among employees. It improves the habits, e.g., recognizing and appreciating colleagues sincerely and working for the betterment of the organization. The practice of compassion at the workplace promotes engagement, dedication, empathy, cooperation, and kindness at the workplace [

39,

40,

55].

The findings of mediation analysis of job stress in a relationship between workplace spirituality and psychological well-being were significantly negative [

51,

52,

96], since it negatively mediates the relation between workplace spirituality and psychological well-being, meaning that with a high level of workplace spirituality, the job stress level will be low, then the psychological well-being level will be high, and vice versa [

44,

50,

71]. Therefore, the findings reflect that job stress should be reduced to achieve optimal performance from university teachers, and job stress damages the psychological well-being of a university teacher [

38,

52,

59]. The relationship between these two variables is a significant negative mediate relationship, which explains that the higher the stress level lower would be the psychological well-being [

2,

54]. The mean of job stress in the current study is more significant, which means the level of job stress is high in participants, even in the presence of moderate workplace spirituality due to the presence of high job stress levels and employee level of psychological well-being. The correlation of its dimensions with the different dimensions of workplace spirituality appears to be low [

58,

60]. It can also be said that due to the low level of workplace spirituality among university teachers, the stress levels were high, and therefore the level of psychological well-being was lower [

37,

66,

68,

70]. Similarly, environmental mastery has a significant and positive impact on the relationship of organizational value, alignment of personal values, and psychological well-being. Previous literature also substantiated that the conducive working environment of an organization alleviated psychological well-being in terms of organizational value and alignment of personal values [

59,

76,

97]. Finally, the mediation of personal growth also enhances the psychological well-being of a university teacher with spiritual orientation [

71,

96,

97].

6. Conclusions

Teaching is the most critical profession in an educated society. With teaching comes excellent responsibilities and distress. It is a lifelong learning process. Day in and out, there are new research findings and discoveries, science is proliferating, and the diffusion of technology has never been at such a pace. To effectively teach, a teacher these days must be familiar with the latest developments, research, discoveries, technologies, trends, and changes. With all such professional responsibilities, it is well understood that teachers are under great psychological stress, performance pressure, and other workplace distress. These challenges and responsibilities are exhausting, which can affect their well-being in challenging modern-day times. It is one of the significant challenges for educational institutes to identify ways to reduce or decrease job stress and improve psychological health and, therefore, better-quality education. The findings of a direct relationship exhibited that the independent variables, such as workplace spirituality, compassion, relationship with others at work, spiritual orientation, organizational value, and alignment of personal values, have a significant and positive relationship with psychological well-being. Teachers’ psychological well-being can be assured with the right workplace environment. Currently, with the rise of new challenges, teachers’ job is more complex. They must adapt to new ways of teaching and ensure that the quality of education is not compromised. Due to the increasing complexity and responsibilities, educational institutes must research positive workplace environment approaches such as workplace spirituality. It can help reduce stress and improve the teachers’ overall mental well-being. The mediation analyses demonstrated that job stress significantly and negatively influences workplace spirituality and psychological well-being. Therefore, the findings reflect that job stress should be reduced to get optimal performance from university teachers, and job stress damages the psychological well-being of a university teacher. Similarly, environmental mastery has a significant and positive impact on the relationship of organizational value, alignment of personal values, and psychological well-being. Thus, the conducive working environment of an organization substantiated the psychological well-being in terms of organizational values and alignment of personal values. Finally, the mediation of personal growth also enhances the psychological well-being of a university teacher with a spiritual orientation. Therefore, it is concluded that overall stress at the workplace is highly affecting the mental state and health of teachers, which affects their output as a teacher to students and their long-term mental and physical health. It is highly recommended that top-tier managers and bosses realize this fact and try to inculcate spirituality and other modern means of reducing job stress and promoting psychological well-being.

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The findings of this research provided a comprehensive conceptual framework to measure the universities’ teachers’ psychological well-being. Therefore, future researchers may replicate the similar model in other industries and other regions of the world since teaching is a profession that involves the highest possible levels of interaction with other people. It does not affect the mental state of the teachers but the students, who are the future of any country. It has been highly recommended for the top management to understand the importance of workplace spirituality. It is essential to understand that since the level of interactions is also high, the job stress that a teacher might feel may be further transmitted to students in terms of harsh behavior or strict checking and marking. Therefore, it must be realized that a healthy mental state will improve a teacher’s performance. If employees practice spirituality in the workplace, and as a result, there would be lesser job stress and more psychological well-being. The management must take appropriate steps to increase workplace spirituality. If higher educational institutes take any initiative to bring positive change, such initiatives are always trendsetters that later can be imparted to industry. It will also help bridge the industry-academia gap. Future research can also be conducted to understand the reason behind the low level of workplace spirituality and how it can be improved.

6.2. Limitations and Areas of Future Studies

This study has shown a statistically robust and significant relation between the direct and indirect association and the variables studied. Likewise, per the experts’ recommendations, the sample size was adequate to build upon the moderate to strong relationships amongst the variables. It has been evident that if the sample size is large, we tend to have more homogeneity, which enables us to have a more accurate prediction value of workplace spirituality for psychological well-being with job stress as a mediating variable. Getting the consent to participate from a particular target group is always tricky, and this is one of the limitations as this might affect the principle of generalization and end up misrepresenting the sample. Another limitation of the study was that we could not keep a balance or control the gender. Although females are fewer in number in terms of employment and higher positions, we still had more female participants. Therefore, it is recommended that future researchers add more female respondents for robust and generalizable outcomes. Moreover, as in the literature, these terms are still in the grooming phase in Pakistan. Therefore, most people and organizations have just started getting familiar with the subject discussed. Over time, once the concepts are fully mature and developed, the results might vary. The undertaken study has addressed the private and public sector universities’ professors. Therefore, it is recommended to the future researchers to replicate their studies in manufacturing and services sectors’ employees. The imperative limitation is not to gauge the cause and effect between the variables. Thus, it is recommended that future researchers conduct their studies by employing cause and effect statistical models [

87].