Impact of Family Functioning on Adolescent Materialism and Egocentrism in Mainland China: Positive Youth Development Attributes as a Mediator

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Family Functioning and Adolescent Materialism

1.1.2. Family Functioning and Adolescent Egocentrism

1.1.3. Positive Youth Development and Adolescent Materialism

1.1.4. Positive Youth Development and Adolescent Egocentrism

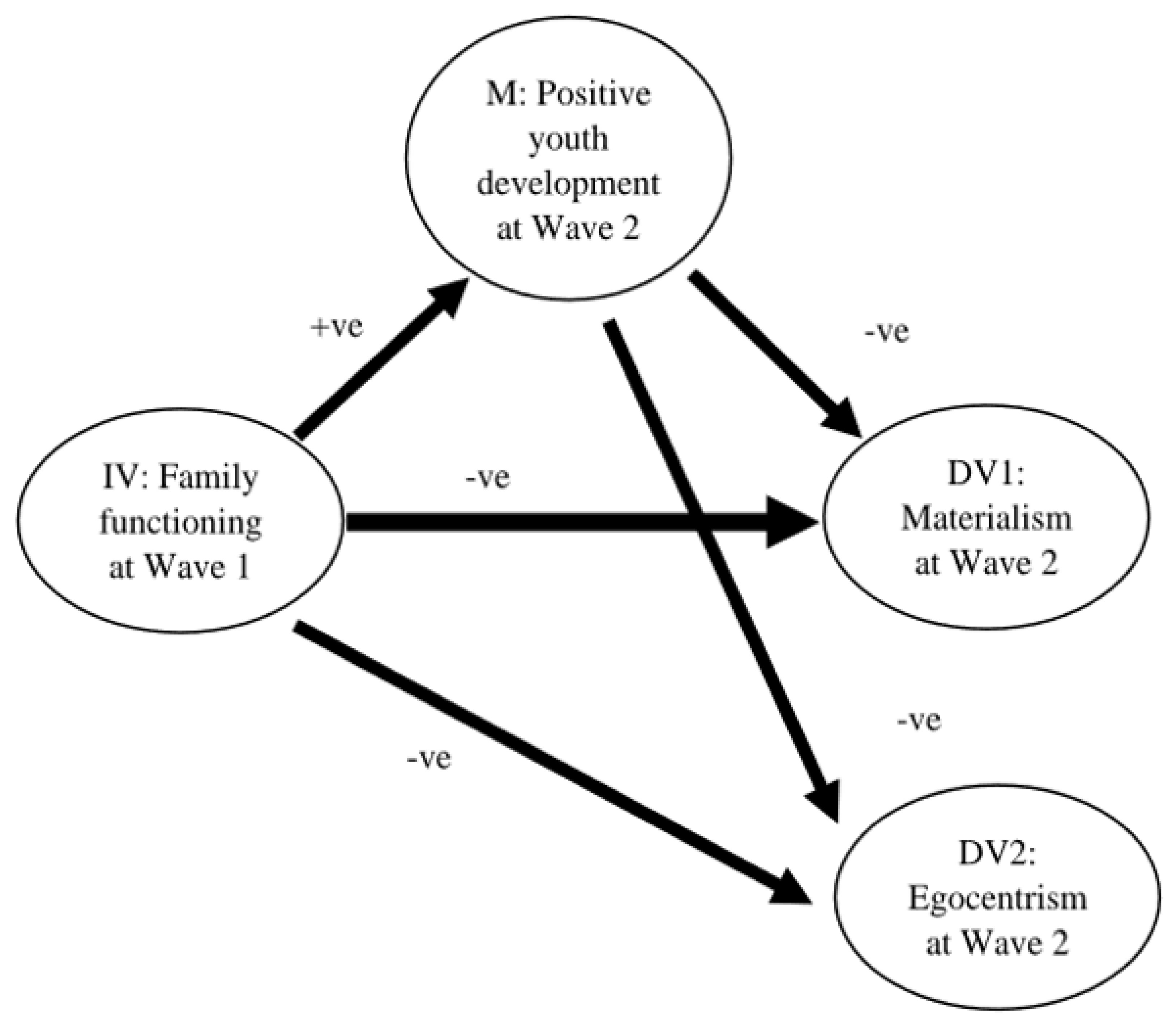

1.1.5. Positive Youth Development as a Mediator in the Linkages from Family Functioning to Adolescent Materialism and Egocentrism

1.2. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Family Functioning

2.2.2. Positive Youth Development

2.2.3. Materialism

2.2.4. Egocentrism

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Attrition Analyses

3.2. Descriptive Statistics, Reliability, and Inter-Correlation

3.3. Scale Validation

3.3.1. Chinese Family Assessment Instrument and Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale

3.3.2. Chinese Adolescent Materialism Scale

3.3.3. Chinese Adolescent Egocentrism Scale

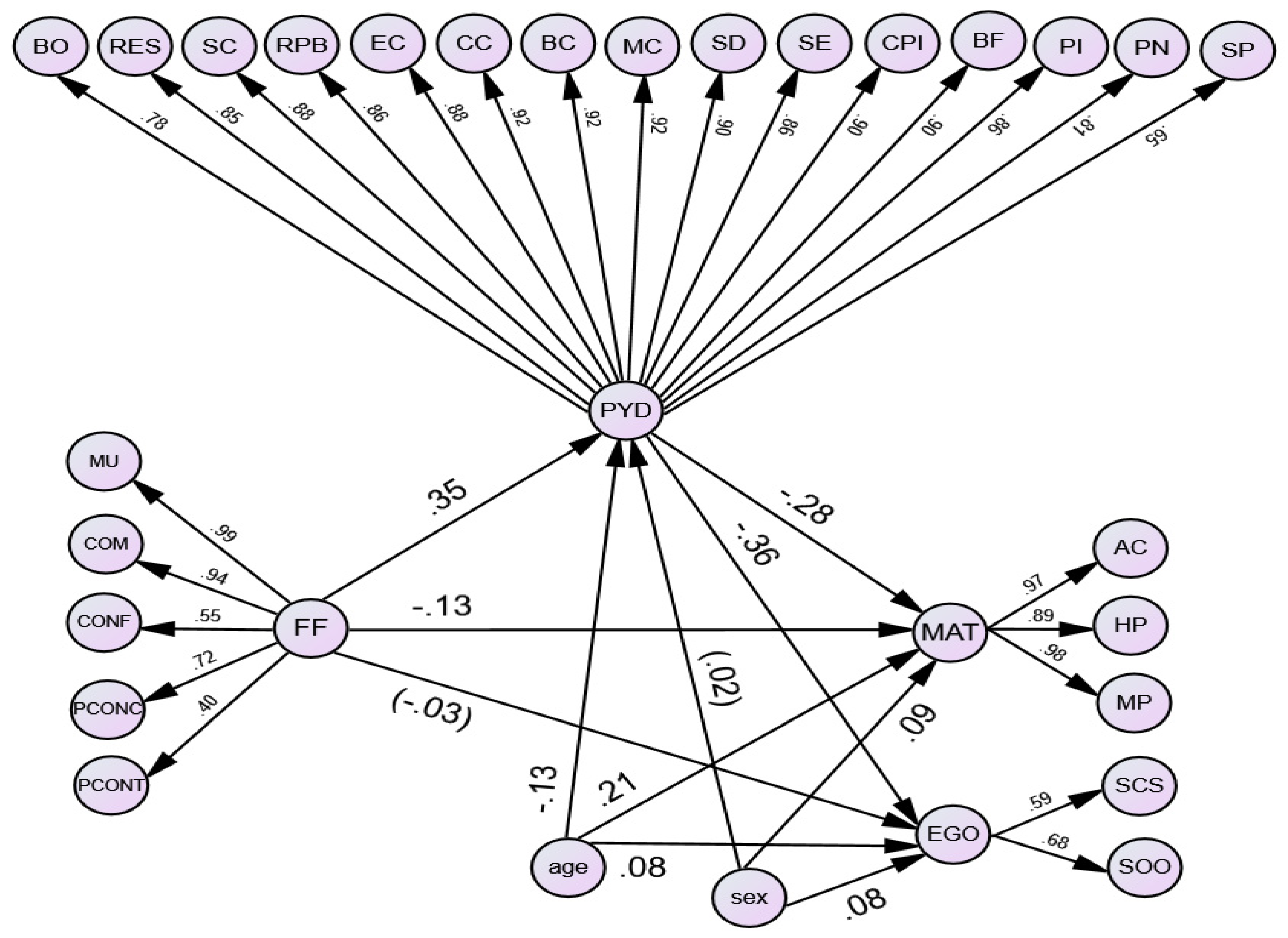

3.4. Prediction and Mediation Analyses

3.4.1. Predictive Effects of Family Functioning and Positive Youth Development on Materialism

3.4.2. Predictive Effects of Family Functioning and Positive Youth Development on Egocentrism

3.4.3. Mediating Effects of Positive Youth Development on the Paths from Family Functioning to Materialism and Egocentrism

4. Discussion

5. Implications

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ioane, B.R. Materialism in China—Review of literature. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2016, 4, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fong, V.L. Little emperors and the 4:2:1 generation: China’s singletons. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, P1137–P1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnish, R.J.; Bridges, K.R.; Gump, J.T.; Carson, A.E. The maladaptive pursuit of consumption: The impact of materialism, pain of paying, social anxiety, social support, and loneliness on compulsive buying. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2019, 17, 1401–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Wang, P.; Liu, S.; Lei, L. Materialism and adolescent problematic smartphone use: The mediating role of fear of missing out and the moderating role of narcissism. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 40, 5842–5850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Morash, M. Materialistic desires or childhood adversities as explanations for girls’ trading sex for benefits. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2016, 60, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preet, K.; Ahluwalia, A.K. Factors of Stress Amongst Students of Professional Institutes. Prabandhan Indian J. Manag. 2019, 12, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J.; Song, Y. Will materialism lead to happiness? A longitudinal analysis of the mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2017, 105, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bester, G. Stress experienced by adolescents in school: The importance of personality and interpersonal relationships. J. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2019, 31, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.R.; de Dreu, C.K.W. Egocentrism drives misunderstanding in conflict and negotiation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 51, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landicho, L.C.; Cabanig, M.C.A.; Cortes, M.S.F.; Villamor, B.J.B. Egocentrism and risk-taking among adolescents. Asia Pac. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2014, 2, 132–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo, A.B.I.; Tan-Mansukhani, R.; Daganzo, M.A.A. Associations between materialism, gratitude, and well-being in children of overseas Filipino workers. Eur. J. Psychol. 2018, 14, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theokas, C.; Lerner, R.M. Observed ecological assets in families, schools, and neighborhoods: Conceptualization, measurement, and relations with positive and negative developmental outcomes. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2006, 10, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A.; Pullig, C.; David, M. Family conflict and adolescent compulsive buying behavior. Young Consum. 2019, 20, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzka, A.M.; Kasser, T.; Niesiobędzka, M.; Lewandowska-Walter, A.; Górnik-Durose, M. Environmental correlates of adolescent’ materialism: Interpersonal role models, media exposure, and family socio-economic status. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2021, 31, 1427–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lei, L.; Wang, P. If you love me, you must do...” Parental psychological control and cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese adolescents. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 37, NP7932–NP7957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Yu, L.; Siu, A.M.H. The Chinese adolescent egocentrism scale: Psychometric properties and normative profiles. Int. J. Disabil. Hum. Dev. 2014, 13, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, X.; Guo, Y. Early material parenting and adolescents’ materialism: The mediating role of overt narcissism. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L.; Fung, A.L.C.; Leung, G.S.M. Perceived overparenting and developmental outcomes among Chinese adolescents: Do family structure and conflicts matter? J. Soc. Pers. Relat. 2021, 38, 742–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attygalle, U.R. Communities, child and adolescent development and mental health. Sri Lanka J. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka, U.; Vandana. Direct and indirect influence of interpersonal and environmental agents on materialism in children. Psychol. Stud. 2016, 61, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folk, J.B.; Brown, L.K.; Marshall, B.D.L.; Ramos, L.M.C.; Gopalakrishnan, L.; Koinis-Mitchell, D. The prospective impact of family functioning and parenting practices on court-involved youth’s substance use and delinquent behavior. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.P.; Connell, C.M.; Wright, G.; Sizer, M.; Norman, J.M.; Hurley, A.; Walker, S.N. An ecological model of home, school, and community partnerships: Implications for research and practice. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 1997, 8, 339–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stormshak, E.A.; Dishion, T.J. An ecological approach to child and family clinical and counseling psychology. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 5, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Tang, X.; Wu, Y.; Tang, X.; Huang, J. Impact of family cohesion and adaptability on academic burnout of Chinese college students: Serial mediation of peer support and positive psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 767676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, J.T.Y.; Shek, D.T.L.; Li, L. Mother-child discrepancy in perceived family functioning and adolescent developmental outcomes in families experiencing economic disadvantage in Hong Kong. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 2036–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L. Family functioning and psychological well-being, school adjustment, and problem behavior in Chinese adolescents with and without economic disadvantage. J. Genet Psychol. 2002, 163, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L. Hong Kong, families in. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Family Studies, 1st ed.; Shehan, C.L., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez, J.F.D.; Bonás, M.C. Influences in children’s materialism: A conceptual framework. Young Consum. 2013, 14, 297–311. [Google Scholar]

- Richins, M.L. Materialism pathways: The processes that create and perpetuate materialism. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 480–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behal, M.; Soni, P. Media use and materialism: A comparative study of impact of television exposure and internet indulgence on young adults. Manag. Labour Stud. 2018, 43, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. The development of materialism in emerging adulthood: Stability, change, and antecedents. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 47, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesselring, T.; Müller, U. The concept of egocentrism in the context of Piaget’s theory. New Ideas Psychol. 2011, 29, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsley, D.K. Toward an integrated theory of adolescent ego development: The “New Look” at adolescent egocentrism. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 1993, 63, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauten, R.L.; Lui, J.H.L.; Doucette, H.; Barry, C.T. Perceived family conflict moderates the relations of adolescent narcissism and CU traits with aggression. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2015, 24, 2914–2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Dou, D.; Zhu, X.; Chai, W. Positive youth development: Current perspectives. Adolesc. Health Med. Ther. 2019, 10, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, J.E.; Chaplin, L.N.; Pandelaere, M.; Norton, M.I.; Ordabayeva, N.; Gunz, A.; Dinauer, L. Using motivation theory to develop a transformative consumer research agenda for reducing materialism in society. J. Public Policy Mark. 2013, 32, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, D.C. Human Motivation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987; pp. 1–663. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality, 2nd ed.; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1970; pp. 1–369. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Lu, M.; Xia, T.; Guo, Y. Materialism as compensation for self-esteem among lower-class students. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2018, 131, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkind, D. Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Dev. 1967, 38, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapsley, D.K.; Murphy, M.N. Another look at the theoretical assumptions of adolescent egocentrism. Dev. Rev. 1985, 5, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macháčková, K.; Dudík, R.; Zelený, J.; Kolářová, D.; Vinš, Z.; Riedl, M. Forest Manners Exchange: Forest as a Place to Remedy Risky Behaviour of Adolescents: Mixed Methods Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubickis, M.; Tan, L.B.G.; Falben, J.K.; Macrae, C.N. The observing self: Diminishing egocentrism through brief mindfulness meditation. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 46, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbate, C.S.; Boca, S.; Gendolla, G.H.E. Self-awareness, perspective-taking, and egocentrism. Self Identity 2016, 15, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Chai, C.W.Y.; Dou, D. Parenting factors and meaning of life among Chinese adolescents: A six-wave longitudinal study. J. Adolesc. 2021, 87, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Leung, K.H.; Dou, D.; Zhu, X. Family functioning and adolescent delinquency in mainland China: Positive youth development attributes as a mediator. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 883439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzcińska, A.; Sekścińska, K. Financial status and materialism—The mediating role of self-esteem. Aust. J. Psychol. 2021, 73, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakhill, J.V.; Cain, K.; Bryant, P.E. The dissociation of word reading and text comprehension: Evidence from component skills. Lang. Cogn. Processes 2003, 18, 443–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakhill, J.V.; Cain, K. The precursors of reading ability in young readers: Evidence from a four-year longitudinal study. Sci. Stud. Read. 2012, 16, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C.; Songco, A.; Parsons, S.; Heathcote, L.; Vincent, J.; Keers, R.; Fox, E. The CogBIAS longitudinal study protocol: Cognitive and genetic factors influencing psychological functioning in adolescence. BMC Psychol. 2017, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, C.; Songco, A.; Parsons, S.; Heathcote, L.C.; Fox, E. The CogBIAS longitudinal study of adolescence: Cohort profile and stability and change in measures across three waves. BMC Psychol. 2019, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Shek, D.T.L.; Zhu, X.; Dou, D. Positive youth development and adolescent depression: A longitudinal study based on mainland Chinese high school students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, D.; Shek, D.T.L. Concurrent and longitudinal relationships between positive youth development attributes and adolescent internet addiction symptoms in Chinese mainland high school students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, D.; Shek, D.T.L.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, L. Dimensionality of the Chinese CES-D: Is it stable across gender, time, and samples? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D.T.L. Assessment of family functioning in Chinese adolescents: The Chinese Family Assessment Instrument. In International Perspectives on Child and Adolescent Ment. Health; Singh, N.N., Ollendick, T., Singh, A.N., Eds.; Elsevier: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zou, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Q. The relationships of family socioeconomic status, parent–adolescent conflict, and filial piety to adolescents’ family functioning in Mainland China. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2014, 23, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Ma, C.M.S. The Chinese family assessment instrument (C-FAI): Hierarchical confirmatory factor analyses and factorial invariance. Res. Social Work Prac. 2010, 20, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Ma, C.M.S. Dimensionality of the Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale: Confirmatory factor analysis. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 98, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.M.S.; Shek, D.T.L. Prevalence and Psychosocial Correlates of After-School Activities among Chinese Adolescents in Hong Kong. Front. Public Health 2014, 2, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Shek, D.T.L. Positive youth development attributes and parenting as protective factors against adolescent social networking addiction in Hong Kong. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 649232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Shek, D.T.L. Predictive effect of positive youth development attributes on delinquency among adolescents in mainland China. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 615900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Ma, C.M.S.; Lin, L. The Chinese adolescent materialism scale: Psychometric properties and normative profiles. In Human Development Research; Shek, D.T.L., Ma, C.M.S., Yu, L., Merrick, J., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 240–253. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Li, X.; Zhu, X.; Shek, E.Y.W. Concurrent and longitudinal predictors of adolescent delinquency in mainland Chinese adolescents: The role of materialism and egocentrism. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, R.; Gore, P.A. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 719–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCallum, R.C.; Browne, M.W.; Sugawara, H.M. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol. Methods 1996, 1, 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonett, D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdil, S.Ö.; Kutlu, Ö. Investigation of the mediator variable effect using BK, sobel and bootstrap methods (mathematical literacy case). Int. J. Progress. Educ. 2019, 15, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, R.S.; Cheung, G.W. Estimating and comparing specific mediation effects in complex latent variable models. Organ. Res. Methods 2012, 15, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T.D. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–386. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Zhu, X. Paternal and maternal influence on delinquency among early adolescents in Hong Kong. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asendorpf, J.B.; van de Schoot, R.; Denissen, J.J.A.; Hutteman, R. Reducing bias due to systematic attrition in longitudinal studies: The benefits of multiple imputation. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2014, 38, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, R.; Kim, J.; Many, J.E. Candidate surveys on program evaluation: Examining instrument reliability, validity and program effectiveness. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2014, 2, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, G.A.; Leech, N.L.; Gloeckner, G.W.; Barrett, K.C. IBM SPSS for Introductory Statistics: Use and Interpretation, 5th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–256. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, K. Development of materialistic values among children and adolescents. Young Consum. 2013, 14, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, J.W.K. Parent-child discrepant effects on positive youth outcomes at the aggregate family functioning context in Hong Kong. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2016, 11, 871–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunzler, D.; Chen, T.; Wu, P.; Zhang, H. Introduction to mediation analysis with structural equation modeling. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry 2013, 25, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, S.; Dey, A.K. Influence of socialisation agents on the materialism of Indian teenagers. Int. J. Indian Cult. Bus. Manag. 2016, 13, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, H.I.; Benmoyal-Bouzaglo, S.; Moschis, G.P.; Smaoui, L. Examination of young adults’ materialism in France and South Africa using two life-course theoretical perspectives. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2015, 36, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrum, L.J.; Chaplin, L.N.; Lowrey, T.M. Psychological causes, correlates, and consequences of materialism. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 5, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Dou, D.; Zhu, X.; Li, X.; Tan, L. Materialism, egocentrism and delinquent behavior in Chinese adolescents in mainland China: A short-term longitudinal study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinski, D.; Kulesza, W.; Muniak, P.; Dolinska, B.; Węgrzyn, R.; Izydorczak, K. Media intervention program for reducing unrealistic optimism bias: The link between unrealistic optimism, well-being, and health. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2021, 14, 499–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib, H.; El-Bassiouny, N. Materialism in young consumers: An investigation of family communication patterns and parental mediation practices in Egypt. J. Islamic Mark. 2011, 3, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shek, D.T.L.; Yu, L. Longitudinal impact of the project PATHS on adolescent risk behavior: What happened after five years? Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 316029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Shek, D.T.L. Impact of a positive youth development program on junior high school students in mainland China: A pioneer study. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 114, 105022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Sex a | 0.00 | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. W1 MU | −0.13 | 0.00 | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. W1 COM | −0.15 | −0.03 | 0.83 | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. W1 CONF | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.44 | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. W1 PCOC | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.65 | 0.58 | 0.52 | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. W1 PCOT | −0.05 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.54 | 0.39 | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. W1 FF | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.69 | - | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 9. W2 BO | −0.11 | 0.00 | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.33 | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 10. W2 RES | −0.14 | −0.02 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.76 | - | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. W2 SC | −0.14 | −0.01 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.63 | 0.69 | - | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. W2 RPB | −0.11 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.69 | 0.66 | 0.71 | - | |||||||||||||||||||

| 13. W2 EC | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.30 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.74 | 0.70 | - | ||||||||||||||||||

| 14. W2 CC | −0.18 | −0.03 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.78 | - | |||||||||||||||||

| 15. W2 BC | −0.14 | −0.01 | 0.26 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.78 | - | ||||||||||||||||

| 16. W2 MC | −0.13 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.73 | 0.75 | - | |||||||||||||||

| 17. W2 SD | −0.16 | −0.01 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.29 | 0.59 | 0.69 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.74 | - | ||||||||||||||

| 18. W2 SE | −0.13 | −0.02 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.66 | - | |||||||||||||

| 19. W2 CPI | −0.18 | −0.07 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.23 | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.69 | 0.73 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.71 | 0.63 | - | ||||||||||||

| 20. W2 BF | −0.20 | −0.02 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.32 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 0.65 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.59 | 0.80 | - | |||||||||||

| 21. W2 PI | −0.19 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.67 | 0.63 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.70 | 0.70 | - | ||||||||||

| 22. W2 PN | −0.11 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.54 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.59 | 0.51 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.73 | - | |||||||||

| 23. W2 SP | −0.13 | −0.10 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 0.58 | 0.52 | 0.38 | - | ||||||||

| 24. W2 PYD | −0.18 | −0.02 | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.75 | 0.69 | - | |||||||

| 25. W2 AC | 0.27 | −0.10 | −0.20 | −0.22 | −0.18 | −0.14 | −0.15 | −0.23 | −0.25 | −0.29 | −0.25 | −0.25 | −0.23 | −0.27 | −0.24 | −0.26 | −0.22 | −0.21 | −0.27 | −0.29 | −0.31 | −0.24 | −0.31 | −0.32 | - | ||||||

| 26. W2 MP | 0.27 | −0.02 | −0.22 | −0.24 | −0.18 | −0.13 | −0.16 | −0.24 | −0.26 | −0.28 | −0.26 | −0.25 | −0.26 | −0.28 | −0.24 | −0.27 | −0.22 | −0.23 | −0.30 | −0.30 | −0.32 | −0.23 | −0.34 | −0.34 | 0.80 | - | |||||

| 27. W2 HP | 0.21 | −0.07 | −0.20 | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.17 | −0.16 | −0.24 | −0.26 | −0.29 | −0.25 | −0.24 | −0.23 | −0.27 | −0.25 | −0.26 | −0.23 | −0.21 | −0.28 | −0.30 | −0.32 | −0.28 | −0.33 | −0.33 | 0.74 | 0.72 | - | ||||

| 28. W2 MAT | 0.28 | −0.06 | −0.23 | −0.25 | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.26 | −0.28 | −0.31 | −0.28 | −0.27 | −0.27 | −0.30 | −0.26 | −0.29 | −0.25 | −0.24 | −0.31 | −0.32 | −0.34 | −0.27 | −0.36 | −0.36 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.88 | - | |||

| 29. W2 SCS | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.14 | - | ||

| 30. W2 SOO | 0.13 | −0.07 | −0.17 | −0.16 | −0.19 | −0.17 | −0.16 | −0.22 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.16 | −0.17 | −0.15 | −0.17 | −0.16 | −0.19 | −0.15 | −0.14 | −0.14 | −0.17 | −0.21 | −0.20 | −0.18 | −0.21 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.32 | - | |

| 31. W2 EGO | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.03 | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.82 | 0.81 | - |

| Mean | 13.1 | - | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 2.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 3.7 | 2.2 | 2.9 |

| SD | 1.32 | - | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.91 | 1.1 | 0.73 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.99 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.87 | 1.4 | 0.83 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.92 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 0.90 |

| α | - | - | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.80 | 0.95 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.85 |

| Mean inter-item correlation | - | - | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 0.57 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.54 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.51 | 0.31 |

| Pathways | Standardized Effects | 95% CI (Lower Bound) | 95% CI (Upper Bound) | Percentage of Indirect Effect in the Total Effect (%) | R2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Materialism | |||||

| Direct effects | |||||

| Family functioning → positive youth development | 0.347 | 0.318 | 0.376 | 43.4 | 19.8 |

| Positive youth development → materialism | −0.281 | −0.328 | −0.234 | ||

| Family functioning → materialism | −0.128 | −0.171 | −0.085 | ||

| Indirect effect | |||||

| Family functioning → positive youth development → materialism | −0.098 | −0.118 | −0.078 | ||

| Total effect | |||||

| Family functioning → materialism | −0.226 | −0.267 | −0.185 | ||

| Egocentrism | |||||

| Direct effects | |||||

| Family functioning → positive youth development | 0.347 | 0.318 | 0.376 | 81.6 | 15.7 |

| Positive youth development → egocentrism | −0.356 | −0.401 | −0.311 | ||

| Family functioning → egocentrism | −0.028 | −0.218 | 0.162 | ||

| Indirect effect | |||||

| Family functioning → positive youth development → egocentrism | −0.124 | −0.177 | −0.071 | ||

| Total effect | |||||

| Family functioning → egocentrism | −0.152 | −0.348 | 0.044 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shek, D.T.L.; Leung, K.H.; Dou, D.; Zhu, X. Impact of Family Functioning on Adolescent Materialism and Egocentrism in Mainland China: Positive Youth Development Attributes as a Mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711038

Shek DTL, Leung KH, Dou D, Zhu X. Impact of Family Functioning on Adolescent Materialism and Egocentrism in Mainland China: Positive Youth Development Attributes as a Mediator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):11038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711038

Chicago/Turabian StyleShek, Daniel Tan Lei, Kim Hung Leung, Diya Dou, and Xiaoqin Zhu. 2022. "Impact of Family Functioning on Adolescent Materialism and Egocentrism in Mainland China: Positive Youth Development Attributes as a Mediator" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 11038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711038

APA StyleShek, D. T. L., Leung, K. H., Dou, D., & Zhu, X. (2022). Impact of Family Functioning on Adolescent Materialism and Egocentrism in Mainland China: Positive Youth Development Attributes as a Mediator. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 11038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711038