Peer Victimization and Adolescent Mobile Social Addiction: Mediation of Social Anxiety and Gender Differences

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Peer Victimization

2.2.2. Social Anxiety

2.2.3. Mobile Social Addiction

2.3. Main Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Mediation Model of Social Anxiety

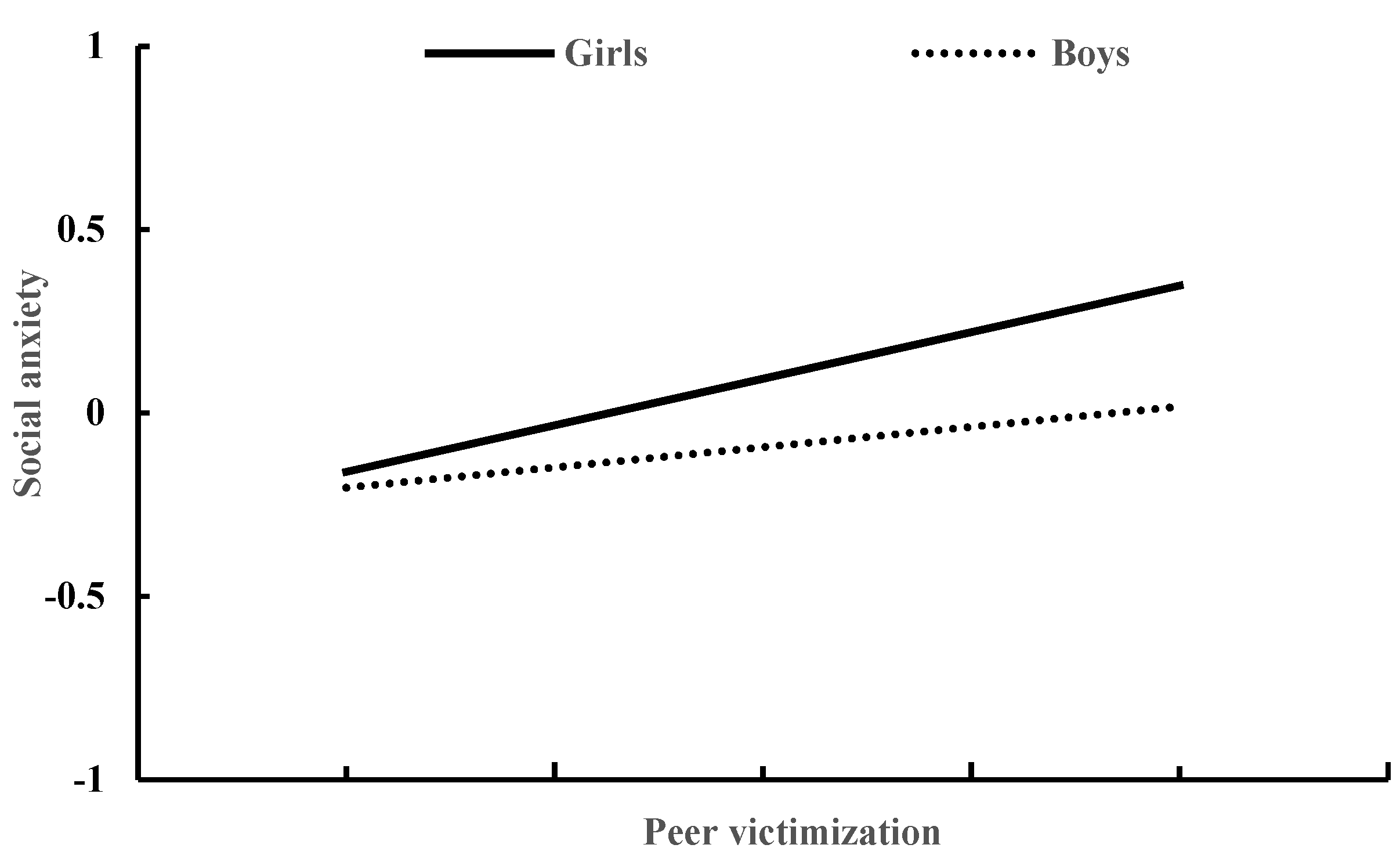

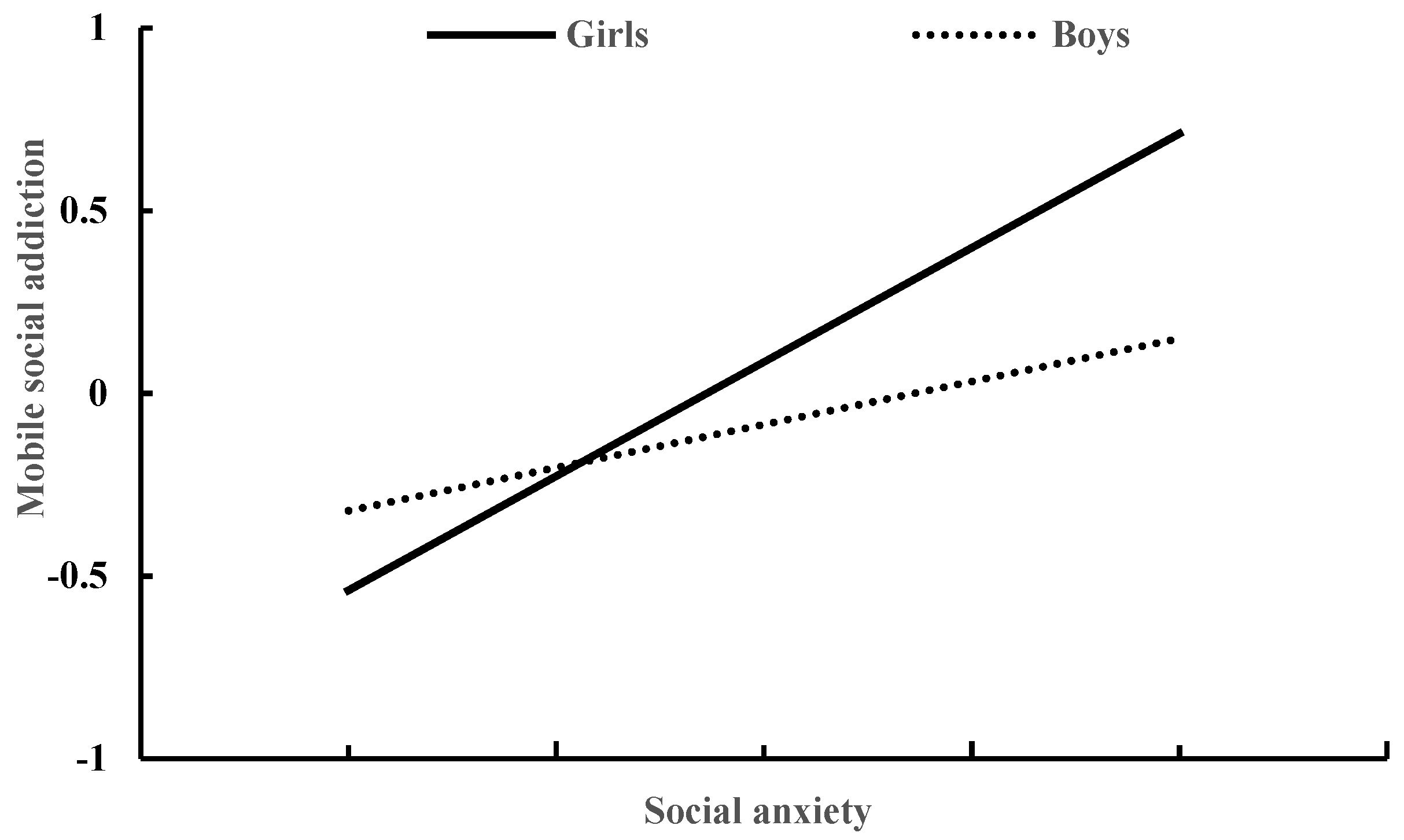

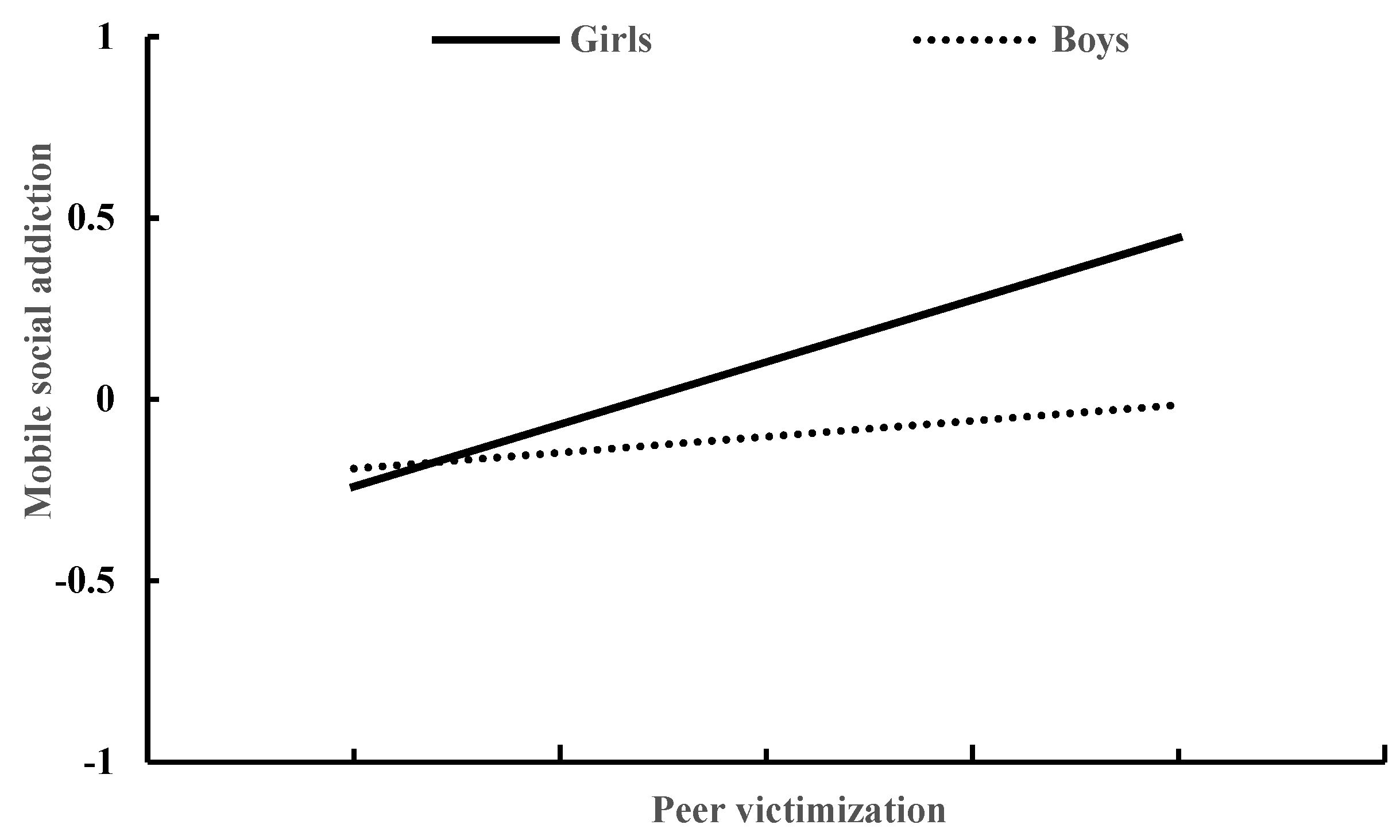

3.3. Moderated Mediation Model of Social Anxiety and Gender

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikhita, C.S.; Jadhav, P.R.; Ajinkya, S.A. Prevalence of mobile phone dependence in secondary school adolescents. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Fernandez, O.; Honrubia-Serrano, M.L.; Freixa-Blanxart, M.; Gibson, W. Prevalence of Problematic Mobile Phone Use in British Adolescents. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, M.; Gandhi, S.; Sharma, M.K. Mobile phone addiction among children and adolescents: A systematic review. J. Addict. Nurs. 2019, 30, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.-Q.; Zhou, Z.-K.; Yang, X.-J.; Kong, F.-C.; Niu, G.-F.; Fan, C.-Y. Mobile phone addiction and sleep quality among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Q.; Fan, C. Mobile Phone Addiction and Adolescents’ Anxiety and Depression: The Moderating Role of Mindfulness. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Yang, S.; Shin, C.-S.; Jang, H. Long-Term Symptoms of Mobile Phone Use on Mobile Phone Addiction and Depression Among Korean Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-Q.; Xu, X.-P.; Yang, X.-J.; Xiong, J.; Hu, Y.-T. Distinguishing Different Types of Mobile Phone Addiction: Development and Validation of the Mobile Phone Addiction Type Scale (MPATS) in Adolescents and Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Yang, X.J.; Nie, Y.G. Interactive effects of cumulative social-environmental risk and trait mindfulness on different types of adolescent mobile phone addiction. In Current Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.-Q.; Yang, X.-J.; Hu, Y.-T.; Zhang, C.-Y.; Nie, Y.-G. How and when is family dysfunction associated with adolescent mobile phone addiction? Testing a moderated mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 111, 104827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Chen, W.; Zhu, X.; He, D. Parents’ phubbing increases Adolescents’ Mobile phone addiction: Roles of parent-child attachment, deviant peers, and gender. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 105, 104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Guan, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, C.; Ma, J.; Zhou, Z. Teacher-student relationships and smartphone addiction: The roles of achievement goal orientation and psychological resilience. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W. Reciprocal longitudinal relations between peer victimization and mobile phone addiction: The explanatory mechanism of adolescent depression. J. Adolesc. 2021, 89, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Zheng, H.; Sun, R.; Lu, S. Parent-adolescent relationships, peer relationships, and adolescent mobile phone addiction: The mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Addict. Behav. 2022, 129, 107260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-Q.; Yang, X.-J.; Hu, Y.-T.; Zhang, C.-Y. Peer victimization, self-compassion, gender and adolescent mobile phone addiction: Unique and interactive effects. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 118, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Yu, C.; Xing, Q.; Liu, Q.; Chen, P. The Influence of Parental Knowledge and Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction on Peer Victimization and Internet Gaming Disorder among Chinese Adolescents: A Mediated Moderation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidman, A.C.; Fernandez, K.C.; Levinson, C.A.; Augustine, A.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Rodebaugh, T.L. Compensatory internet use among individuals higher in social anxiety and its implications for well-being. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2012, 53, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.-X.; Fang, X.-Y.; Wan, J.-J.; Zhou, Z.-K. Need satisfaction and adolescent pathological internet use: Comparison of satisfaction perceived online and offline. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Zhao, L. Peer victimization and adolescent Internet addiction: The mediating role of psychological security and the moderating role of teacher-student relationships. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkis, Y.; Kadirhan, Z.; Sat, M. Development and Validation of Social Anxiety Scale for Social Media Users. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision: Arlington, TX, USA, 2013; pp. 189–235. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2001, 17, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayazi, M.; Hasani, J. Structural relations between brain-behavioral systems, social anxiety, depression and internet addiction: With regard to revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (r-RST). Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Mak, K.; Watanabe, H.; Jeong, J.; Kim, D.; Bahar, N.; Ramos, M.; Chen, S.; Cheng, C. The mediating role of Internet addiction in depression, social anxiety, and psychosocial well-being among adolescents in six Asian countries: A structural equation modelling approach. Public Health 2015, 129, 1224–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Cheng, H.; Zhai, Z.; Liu, H. Relationship between Social Anxiety and Internet Addiction in Chinese College Students Controlling for the Effects of Physical Exercise, Demographic, and Academic Variables. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Qin, J.; Huang, B.; Zhang, H.; Lei, L. The effect of social anxiety on mobile phone dependence among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 108, 104517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X. How does self-esteem affect mobile phone addiction? The mediating role of social anxiety and interpersonal sensitivity. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 271, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, X. The association between social anxiety and mobile phone addiction: A three-level meta-analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 130, 107198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.M.; Betz, N.E. Development and Validation of a Scale of Perceived Social Self-Efficacy. J. Career Assess. 2000, 8, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, N.E. Self-Efficacy Theory as a Basis for Career Assessment. J. Career Assess. 2000, 8, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olenik-Shemesh, D.; Heiman, T. Cyberbullying Victimization in Adolescents as Related to Body Esteem, Social Support, and Social Self-Efficacy. J. Genet. Psychol. 2016, 178, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victoira, L.P.; Andrews, J.J.; Nordstokke, D. Peer victimization and anxiety in youth: A moderated mediation of peer perceptions and social self-efficacy. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.S.; La Greca, A.M.; Harrison, H.M. Peer Victimization and Social Anxiety in Adolescents: Prospective and Reciprocal Relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storch, E.A.; Masia-Warner, C.; Crisp, H.; Klein, R.G. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescence: A prospective study. Aggress. Behav. 2005, 31, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranta, K.; Kaltiala-Heino, R.; Koivisto, A.-M.; Tuomisto, M.T.; Pelkonen, M.; Marttunen, M. Age and gender differences in social anxiety symptoms during adolescence: The Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) as a measure. Psychiatry Res. 2007, 153, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballo, V.E.; Salazar, I.C.; Irurtia, M.J.; Arias, B.; Hofmann, S.G.; CISO-A Research Team. Social anxiety in 18 nations: Sex and age differences. Behav. Psychol. 2008, 16, 163–187. [Google Scholar]

- Asher, M.; Asnaani, A.; Aderka, I.M. Gender differences in social anxiety disorder: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.I.; Hong, F.Y.; Chiu, S.L. An analysis on the correlation and gender difference between college students’ Internet addiction and mobile phone addiction in Taiwan. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, L.; Hadwin, J.A.; Kovshoff, H. The Role of Peers in the Development of Social Anxiety in Adolescent Girls: A Systematic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2019, 5, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J.V.; Chen, Y.; Huang, C.-C. Children’s exposure to intimate partner violence and peer bullying victimization. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 91, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.D.; Wang, X.L.; Ma, H. Handbook of Mental Health Assessment; Chinese Mental Health Journal Press: Beijing, China, 1999; pp. 490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Fenigstein, A.; Scheier, M.F.; Buss, A.H. Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1975, 43, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–507. [Google Scholar]

- Kirik, A.; Arslan, A.; Çetinkaya, A.; Mehmet, G.Ü.L. A quantitative research on the level of social media addiction among young people in Turkey. Int. J. Sport Cult. Sci. 2015, 3, 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- Gazi, M.A.; Çetin, M.; Çakı, C. The research of the level of social media addiction of university students. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 2017, 3, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Martínez, P.; Ruiz-Rubio, M.; Perea-Moreno, A.-J.; Martínez-Jiménez, M.P.; Pagliari, C.; Redel-Macías, M.D.; Vaquero-Abellán, M. Gender differences in the addiction to social networks in the Southern Spanish university students. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 46, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Han, X.; Yu, H.; Wu, Y.; Potenza, M.N. Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 113, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, C.P.; Anderson, E.R. Brave men and timid women? A review of the gender differences in fear and anxiety. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 29, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballo, V.E.; Salazar, I.C.; Irurtia, M.J.; Arias, B.; Hofmann, S.G.; Ciso-A Research Team. Differences in social anxiety between men and women across 18 countries. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014, 64, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dailey, S.L.; Howard, K.; Roming, S.M.P.; Ceballos, N.; Grimes, T. A biopsychosocial approach to understanding social media addiction. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Califf, C.B.; Featherman, M. Can Social Role Theory Explain Gender Differences in Facebook Usage? In Proceedings of the 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, 7–10 January 2013; pp. 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Stockton, H. The multidimensional peer victimization scale: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 42, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.G.; Rawana, E.P.; Brownlee, K.; Whitley, J. An investigation of the relationship between psychological strengths and the perception of bullying in early adolescents in schools. Alta. J. Educ. Res. 2010, 56, 470–481. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo-Baum, K.; Knappe, S.; Fehm, L.; Höfler, M.; Lieb, R.; Hofmann, S.G.; Wittchen, H.-U. The natural course of social anxiety disorder among adolescents and young adults. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2012, 126, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontillo, M.; Tata, M.C.; Averna, R.; Demaria, F.; Gargiullo, P.; Guerrera, S.; Pucciarini, M.L.; Santonastaso, O.; Vicari, S. Peer Victimization and Onset of Social Anxiety Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orpinas, P.; McNicholas, C.; Nahapetyan, L. Gender differences in trajectories of relational aggression perpetration and victimization from middle to high school. Aggress. Behav. 2015, 41, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.P.; Whisman, M.A. Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2013, 55, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jose, P.E.; Brown, I. When does the Gender Difference in Rumination Begin? Gender and Age Differences in the Use of Rumination by Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2007, 37, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.C.; Dietrich, M.S. Stressful Life Events, Worry, and Rumination Predict Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Young Adolescents. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2015, 28, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F. Rumination and worry as mediators of the relationship between self-compassion and depression and anxiety. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2010, 48, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Group | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer victimization | Girls | 1.80 | 0.74 | 3.36 | <0.01 |

| Boys | 1.62 | 0.61 | |||

| Social anxiety | Girls | 2.10 | 0.96 | 3.27 | <0.01 |

| Boys | 1.86 | 0.90 | |||

| Mobile social addiction | Girls | 2.64 | 1.20 | −3.71 | <0.001 |

| Boys | 2.31 | 1.01 |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Peer victimization | - | 0.16 *** | 0.14 *** |

| 2. Social anxiety | 0.40 *** | - | 0.28 *** |

| 3. Mobile social addiction | 0.51 *** | 0.64 *** | - |

| Outcome Variables | Independent Variables | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile social addiction | Age | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.12 | 0.26 | |

| Peer victimization | 0.36 *** | 0.04 | 8.53 | <0.001 | |

| Social anxiety | Age | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.89 | 0.37 |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.06 * | 0.03 | 1.99 | <0.05 | |

| Peer victimization | 0.30 *** | 0.04 | 8.36 | <0.001 | |

| Mobile social addiction | Age | −0.002 | 0.03 | −0.07 | 0.95 |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.43 | 0.67 | |

| Peer victimization | 0.24 *** | 0.04 | 6.11 | <0.001 | |

| Social anxiety | 0.41 *** | 0.04 | 11.60 | <0.001 |

| β | SE | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator variable model for predicting social anxiety | ||||

| Age | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.01 | 0.31 |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.07 * | 0.03 | 2.13 | <0.05 |

| Gender | 0.19 * | 0.08 | 2.48 | <0.05 |

| Peer victimization | 0.27 *** | 0.03 | 7.80 | <0.001 |

| Peer victimization × Gender | 0.21 ** | 0.07 | 3.18 | <0.01 |

| Dependent variable model for predicting mobile social addiction | ||||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.80 |

| Daily mobile phone use time | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 0.54 |

| Gender | 0.14 * | 0.07 | 2.04 | <0.05 |

| Peer victimization | 0.20 *** | 0.04 | 4.63 | <0.001 |

| Social anxiety | 0.39 *** | 0.04 | 11.03 | <0.001 |

| Peer victimization × Gender | 0.21 * | 0.08 | 2.50 | <0.05 |

| Social anxiety × Gender | 0.30 *** | 0.07 | 4.30 | <0.001 |

| Conditional direct effect analysis at values of the moderator (gender) | β | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| Boys | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.24 |

| Girls | 0.30 *** | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.39 |

| Conditional indirect effect analysis at values of the moderator (gender) | β | Boot SE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

| Boys | 0.04 ** | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Girls | 0.20 *** | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.26 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tu, W.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Q. Peer Victimization and Adolescent Mobile Social Addiction: Mediation of Social Anxiety and Gender Differences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710978

Tu W, Jiang H, Liu Q. Peer Victimization and Adolescent Mobile Social Addiction: Mediation of Social Anxiety and Gender Differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710978

Chicago/Turabian StyleTu, Wei, Hui Jiang, and Qingqi Liu. 2022. "Peer Victimization and Adolescent Mobile Social Addiction: Mediation of Social Anxiety and Gender Differences" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710978

APA StyleTu, W., Jiang, H., & Liu, Q. (2022). Peer Victimization and Adolescent Mobile Social Addiction: Mediation of Social Anxiety and Gender Differences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10978. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710978