Mea Culpa! The Role of Guilt in the Work-Life Interface and Satisfaction of Women Entrepreneur

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Conflict, Guilt, Job Satisfaction and Life Satisfaction

1.2. The Moderating Role of Enrichment

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Guilt

2.2.2. Work–Family Interface

2.2.3. Life Satisfaction

2.2.4. Job Satisfaction

2.3. Data Analisys

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Testing for Mediation Effect

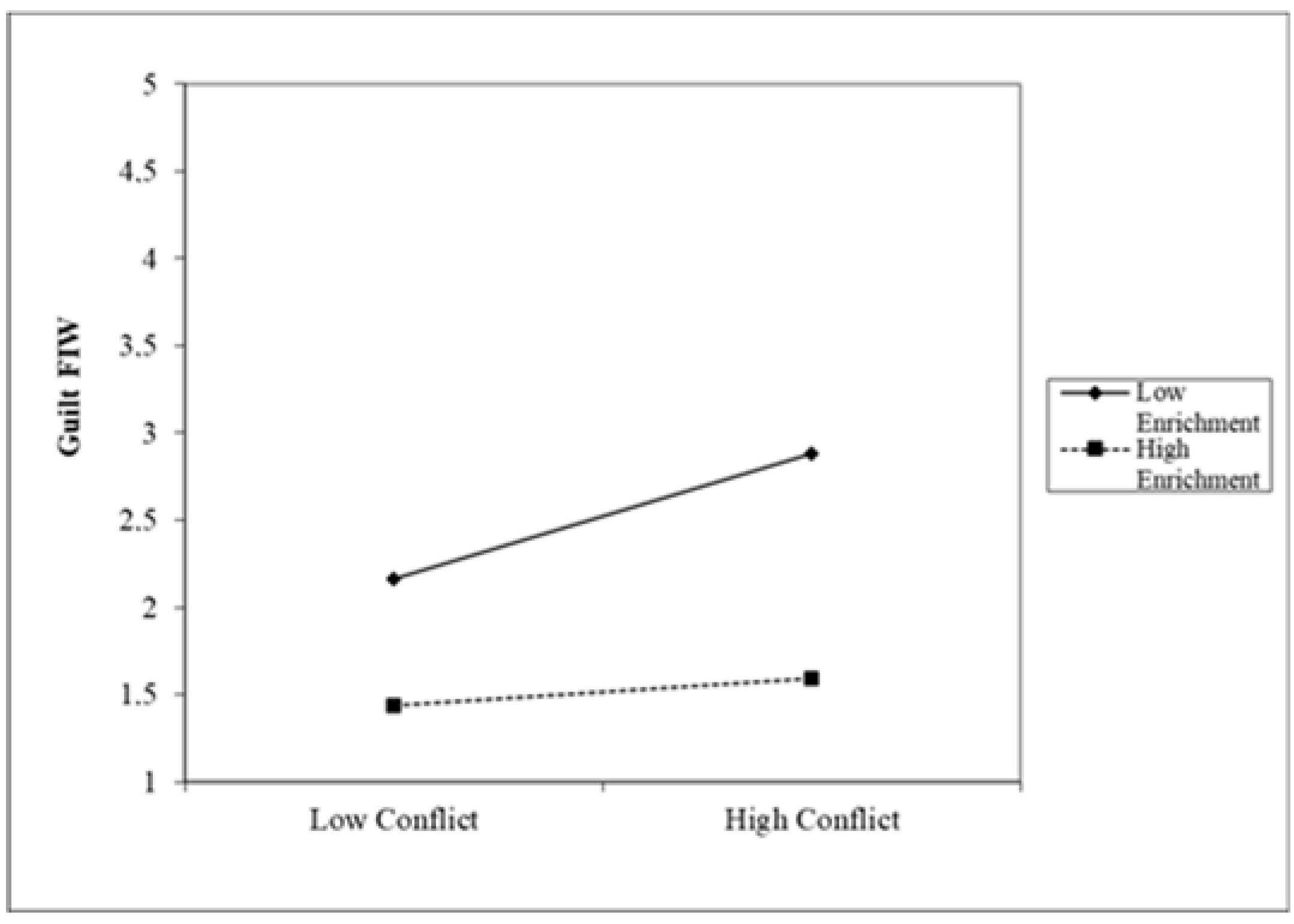

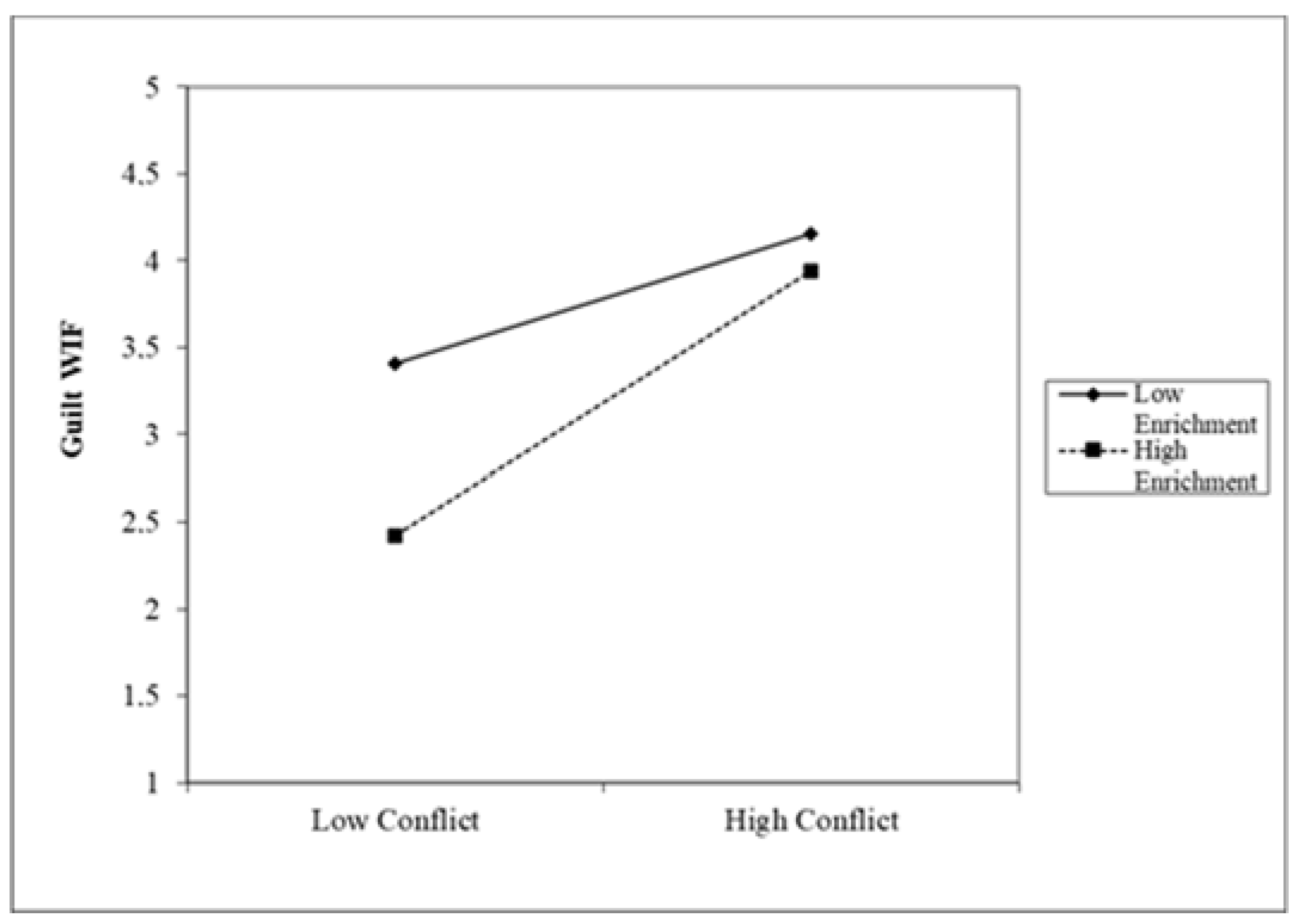

3.3. Moderated Mediation Effect Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Osservatorio Sull’imprenditoria Femminile. Available online: https://www.imprenditoriafemminile.camcom.it/P43K491O0/dati.htm (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Ryff, C.D. Eudaimonic well-being, inequality, and health: Recent findings and future directions. Int. Rev. Econ. 2017, 64, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective wellbeing. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, M.; Coad, A. Life satisfaction and self-employment: A matching approach. Small Bus. Econ. 2013, 40, 1009–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyubomirsky, S.; King, L.; Diener, E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychol. Bull. 2005, 131, 803–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wincent, J.; Örtqvist, D.; Drnovsek, M. The entrepreneur’s role stressors and proclivity for a venture withdrawal. Scand. J. Manag. 2008, 24, 232–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E. Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—Self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—With job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, M.; Poggesi, S.; De Vita, L. Italian women entrepreneurs: An empirical investigation. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference of the British Academy of Management (BAM) Belfast, North Ireland, 9–11 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, J.E.; McDougald, M.S. Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggesi, S.; Mari, M.; De Vita, L. Women entrepreneurs and work-family conflict: An analysis of the antecedents. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2019, 15, 431–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggesi, S.; Mari, M.; De Vita, L. What’s new in female entrepreneurship research? Answers from the literature. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2016, 12, 735–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada Publications. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H72-21-186-2003E.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Fahlén, S. Does gender matter? Policies, norms and the gender gap in work to-home and home-to-work conflict across Europe. Community Work Fam. 2014, 17, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Zvonkovic, A.M.; Crawford, D.W. The impact of work-family conflict and facilitation on women’s perceptions of role balance. J. Fam. Issues 2014, 35, 1252–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnity, F.; Calvert, E. Work-life Conflict and Social Inequality in Western Europe. Soc. Indic. Res. 2009, 93, 489–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscocco, K.A.; Robinson, J.; Hall, R.H.; Allen, J.K. Gender and small business success: An inquiry into women’s relative disadvantage. Soc. Forces 1991, 70, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Choo Ling, S. Work-Family Conflict of Women Entrepreneurs in Singapore. Women Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 16, 204–221. [Google Scholar]

- DeMartino, R.; Barbato, R.; Jacques, P.H. Exploring the career /achievement and personal life orientation differences between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs: The impact of sex and dependents. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruderman, M.; Ohlott, P.; Panzer, K.; King, S. Benefits of multiple roles for managerial women. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Cliff, J.E. The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. OB and entrepreneurship: The reciprocal benefits of closer conceptual links. Res. Organ. Behav. 2002, 24, 225–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMartino, R.; Barbato, R.; Jacques, P.H. Differences Among Women and Men MBA Entrepreneurs: Exploring Family Flexibility and Wealth Creation as Career Motivators. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 815–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscocco, K.A. Work–family linkages among self-employed women and men. J. Vocat. Behav. 1997, 50, 204–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, E.G.; Heck, R.K.Z. Evolving research in entrepreneurship and family business: Recognizing family as the oxygen that feeds the fire of entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, D.; Wiklund, J.; Anderson, S.; Coffey, B. Entrepreneurial exit intentions and the business-family interface. J. Bus. Ventur. 2016, 31, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscocco, K.; Bird, S.R. Gendered paths: Why women lag behind men in small business success. Work Occup. 2012, 39, 183–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesaroni, F.M.; Pediconi, M.G.; Sentuti, A. It’s always a women’s problem! Micro-entrepreneurs, work-family balance and economic crisis. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, A.S.; Erickson, R.I. Managing emotions on the job and at home: Understanding the consequences of multiple emotional roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1993, 18, 457–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, A.; Ryan, A.M. The Importance of the Individual: How Self-Evaluations Influence the Work-Family Interface. In Work and Life Integration: Organizational, Cultural, and Individual Perspectives; Kossek, E.E., Lambert, S.J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 193–209. [Google Scholar]

- Shipley, P.; Coats, M. A community study of dual-role stress and coping in working mothers. Work Stress 1992, 6, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvin-Nowak, Y. The meaning of guilt: A phenomenological description of employed mothers’ experiences of guilt. Scand. J. Psychol. 1999, 40, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Priola, V. “What’s women’s work?” Work-family interface among women entrepreneurs in Italy. In Handbook of Gendered Careers in Management: Getting in, Getting on, Getting out; Broadbridge, A.M., Fielden, S.L., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2015; pp. 390–408. [Google Scholar]

- Neider, L. A preliminary investigation of female entrepreneurs in Florida. J. Small Bus. Manag. 1987, 25, 22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Fenwick, T.J. Lady, Inc.: Women learning, negotiating subjectivity in entrepreneurial discourses. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 2002, 21, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, W.M.Y.; Chong, C.W.; Yuen, Y.Y.; Chong, S.C. Exploring SME Women Entrepreneurs’ Work–Family Conflict in Malaysia. In Entrepreneurial Activity in Malaysia; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2021; pp. 157–183. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, L.; Mari, M.; Poggesi, S. Work-family conflicts and satisfaction among Italian women entrepreneurs. In Wellbeing of Women in Entrepreneurship. A Global Perspective; Maria-Teresa, L., Kuschel, K., Beutell, N., Pouw, N., Eijdenberg, E.L., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; p. 452. [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq, D.; Brieger, S.A.; Welzel, C. Leveraging the macro-level environment to balance work and life: An analysis of female entrepreneurs’ job satisfaction. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 56, 1361–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neneh, B.N. Family support and performance of women-owned enterprises: The mediating effect of family-to-work enrichment. J. Entrep. 2017, 26, 196–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, A.; Khandelwal, P. Work–family interface of women entrepreneurs: Evidence from India. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2020, 9, 411–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.H.; Kaciak, E. Women’s entrepreneurship: A model of business-family interface and performance. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2018, 14, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İplik, E.; Ülbeği, İ.D. The Effect of Work-Family Enrichment on Career and Life Satisfaction of Women Entrepreneurs. OPUS Int. J. Soc. Res. 2021, 18, 5157–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinsmyth, C. Mothers’ business, work/life and the politics of ‘mumpreneurship’. Gend. Place Cult. 2014, 21, 1230–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D. Constraints and opportunities facing women entrepreneurs in developing countries: A relational perspective. Gend. Manag. 2009, 24, 232–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, R.; Ganesh, S. Empowerment, constraint, and the entrepreneurial self: A study of white women entrepreneurs. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2007, 35, 268–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social Exchange Theory: An Interdisciplinary Review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P.M. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; p. 372. [Google Scholar]

- Rauch, A.; Fink, M.; Hatak, I. Stress processes: An essential ingredient in the entrepreneurial process. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 340–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, U. Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: A review and research agenda. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 32, 290–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Nikolaev, B.; Shir, N.; Foo, M.D.; Bradley, S. Entrepreneurship and well-being: Past, present, and future. J. Bus. Ventur. 2019, 34, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.H.; Miyasaki, N.N.; Watters, C.E.; Coombes, S.M. The dilemma of growth: Understanding venture size choices of women entrepreneurs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 44, 221–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Lenka, U. Study on work-life balance of women entrepreneurs—Review and research agenda. Ind. Commer. Train. 2015, 47, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, B.J. Recent developments in role theory. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1986, 12, 67–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, N.P. Enriching or depleting? The dynamics of engagement in work and family roles. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Herst, D.; Bruck, C.; Sutton, M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 278–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.; Sousa, C.; Santos, J.; Silva, T.; Korabik, K. Portuguese mothers and fathers share similar levels of work-family guilt according to a newly validated measure. Sex Roles 2018, 78, 194–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ilies, R.; De Pater, I.; Lim, S.; Binnewies, C. Attributed causes for work-family conflict: Emotional and behavioral outcomes. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 2, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J. Assessing individual differences in proneness to shame and guilt: Development of the self-conscious affect and attribution inventory. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermot, C. Guilt: A gendered bond within the transnational family. Emot. Space Soc. 2015, 16, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubany, E. A cognitive model of guilt typology in combat-related PTSD. J. Trauma. Stress 1994, 7, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahn-Waxler, C.; Kochanska, G.; Krupnick, J.; McKnew, D. Patterns of guilt in children of depressed and well mothers. Dev. Psychol. 1990, 26, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conlin, M. The new debate over working moms: As more moms choose to stay home, office life is again under fire. Bus. Week 2000, 3699, 102–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, E. Work and family (a special report): Regailabing a balance—This is home; This is work. Wall Str. J. 1997, 1997, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.; Powell, G. When work and family collide: Deciding between competing role demands. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2003, 90, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.; Allen, D. Relationship between work interference with family and parent–child interactive behavior: Can guilt help? J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 276–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korabik, K. The intersection of gender and work-family guilt. In Gender and the Work-Family Experience: An Intersection of Two Domains; Mills, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Aycan, Z.; Eskin, M. Relative contribution of childcare, spousal, and organizational support in reducing work-family conflict for males and females: The case of Turkey. Sex Roles 2005, 53, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, J. Entrepreneurship: Not an easy path to top management for women. Women Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 19, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amstad, F.T.; Meier, L.L.; Fasel, U.; Elfering, A.; Semmer, N.K. A meta-analysis of work-family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011, 16, 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.; Heinen, B.; Langkamer, K. Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 57–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Ozeki, C. Bridging the work-family policy and productivity gap. Int. Community Work Fam. 1998, 2, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruck, C.S.; Allen, T.D.; Spector, P.E. The relation between work-family conflict and job satisfaction: A finer-grained analysis. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 60, 336–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boles, J.S.; Wood, J.A.; Johnson, J. Interrelationships of role conflict, role ambiguity, and work-family conflict with different facets of job satisfaction and the moderating effects of gender. J. Pers. Sell. Sales Manag. 2003, 23, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, D.S.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Kacmar, K.M. The relationship of schedule flexibility and outcomes via the work-family interface. J. Manag. Psychol. 2010, 25, 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrewe, P.L.; Hochwarter, W.A.; Kiewitz, C. Value attainment: An explanation for the negative effects of work-family conflict on job and life satisfaction. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1999, 4, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frone, M.R. Work-family balance. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; pp. 143–162. [Google Scholar]

- Geurts, S.A.E.; Kompier, M.A.J.; Roxburgh, S.; Houtman, I.L.D. Does work-home interference mediate the relationship between workload and well-being? J. Vocat. Behav. 2003, 63, 532–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Googins, B.; Burden, D. Vulnerability of working parents: Balancing work and home roles. Soc. Work 1987, 32, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedeian, A.T.; Burke, B.G.; Moffett, R.G. Outcomes of work-family conflict among married male and female professionals. J. Manag. 1988, 14, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work-family conflict and family-work conflict scales. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treistman, D.L. Work-Family Conflict and Life Satisfaction in Female Graduate Students: Testing Mediating and Moderating Hypotheses. Ph.D. Theis, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, May 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, C.; Gonçalves, G.; Sousa, A.; Silva, T.; Santos, J. Gestão da interface trabalho-família e efeitos na satisfação com a vida e na paixão com o trabalho [The work family interface management and the effects on satisfaction with life and passion for work]. In Occupational Safety and Hygiene SHO2016—Proceedings Book; Arezes, P., Baptista, J., Barroso, M., Carneiro, P., Cordeiro, P., Costa, N., Melo, R., Miguel, A., Perestrelo, G., Eds.; CRC Press: Guimarães, Portugal, 2016; pp. 338–340. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, C.; Pinto, E.; Santos, J.; Gonçalves, G. Effects of work-family and family-work conflict and guilt on job and life satisfaction. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 51, 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, K.; Korabik, K. Does work-to-family guilt mediate the relationship between work-to-family conflict and job satisfaction? Testing the moderating roles of segmentation preference and family collectivism orientation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 48, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergeneli, A.; Ilsev, A.; Karapınar, P.B. Work–family conflict and job satisfaction relationship: The roles of gender and interpretive habits. Gend. Work Organ. 2010, 17, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, S.R. Multiple roles and role strain: Some notes on human energy, time and commitment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1977, 42, 921–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.C. Toward a review and reconceptualization of the work/family literature. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 1998, 124, 125–182. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, N.G.; Eddleston, A.K. Work–family enrichment and entrepreneurial success: Do female entrepreneurs benefit most? Acad. Manag. Proc. 2011, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eby, L.; Casper, W.; Lockwood, A.; Bordeaux, C.; Brinley, A. Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002). J. Vocat. Behav. 2005, 66, 124–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönlund, A. More control, less conflict? Job demand–control, gender and work–family conflict. Gend. Work Organ. 2007, 14, 476–497. [Google Scholar]

- Korabik, K.; Lero, D.S.; Whitehead, D. Handbook of Work-Family Integration: Research, Theory, and Best Practices. Elseiver: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Butler, A.B. The impact of job characteristics on work-to-family facilitation: Testing a theory and distinguishing a construct. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E.J. Work-family facilitation and conflict: Working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. J. Fam. Issues 2005, 26, 793–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, D.; Kacmar, K.M.; Wayne, J.H.; Grzywacz, J.G. Measuring the positive side of the work-family interface: Development and validation of a work-family enrichment scale. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Marks, N.F. Reconceptualizing the work–family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyar, S.L.; Mosley, D.C. The relationship between core self-evaluations and work and family satisfaction: The mediating role of work-family conflict and facilitation. J. Vocat. Behav. 2007, 71, 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmforth, K.; Gardner, D. Conflict and facilitation between work and family: Realizing the outcomes for organizations. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2006, 35, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Hochwarter, W.A.; Perrewé, P.L.; Meurs, J.A.; Kacmar, C. The interactive effects of work-induced guilt and ability to manage resources on job and life satisfaction. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J.; El-Kot, E.G. Correlates of work-family conflicts among managers in Egypt. Int. J. Islam. Middle East. 2010, 3, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Geurts, S.A.E. Towards a typology of work-home interaction. Community Work Fam. 2004, 7, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gareis, K.C.; Barnett, R.C.; Ertel, K.A.; Berkman, L.F. Work-family enrichment and conflict: Additive effects, buffering, or balance? J. Marriage Fam. 2009, 71, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwain, A.; Korabik, K.; Chappell, D.B. The work-family guilt scale. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Canadian Psychological Association, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- McElwain, A.K. An Examination of the Reliability and Validity of the Work-Family Guilt Scale. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Guelph, Guelph, Canada, December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnunen, U.; Feldt, T.; Geurts, S.; Pulkkinen, L. Types of workfamily interface: Well-being correlates of negative and positive spillover between work and family. Scand. J. Psychol. 2006, 47, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Agus, M.; Lasio, D.; Serri, F. Development and validation of a measure of work-family interface. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 34, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lance, C.E.; Lautenschlager, G.J.; Sloan, C.E.; Varca, P.E. A comparison between bottom-up, top-down, and bidirectional models of relationships between global and life facet satisfaction. J. Personal. 1989, 57, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T.A.; Locke, E.A.; Durham, C.C.; Kluger, A.N. Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, R.M. A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 732. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, A.D.; Sortheix, F.M. Work-family values, priority goals and life satisfaction: A seven year follow-up of MBA students. J. Happiness Stud. 2012, 13, 1131–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.T. Promoting work/family balance: An organization-change approach. Organ. Dyn. 1990, 18, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Priola, V. “Who’s that Girl?” The entrepreneur as a super(wo)man. Can. J. Adm. Sci. 2021, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J. ‘Failure rates for female controlled businesses: Are they any different?’. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2003, 41, 262–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, A.; Gherardi, S.; Poggio, B. Doing gender, doing entrepreneurship: An ethnographic account of intertwined practices. Gend. Work Organ. 2004, 11, 406–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, H. Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, A. A Framework for the Development of Women Entrepreneurship in the Ekurhuleni District. Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Thibodeau, R.; Jorgensen, R.S. Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 137, 68–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Mises, L. Human Action; Ludwig von Mises Institute: Auburn, AL, USA, 1949/1988; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, N.J.; Klein, P.G. Organizing Entrepreneurial Judgment: A New Approach to the Firm; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; p. 299. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Casas, V. Ludwig von Mises as feminist economist. Indep. Rev. J. Polit. Econ. 2021, 26, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boettke, P. Economics and public administration. South. Econ. J. 2018, 84, 938–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasio, D.; Putzu, D.; Serri, F.; De Simone, S. Il divario di genere nel lavoro di cura e la conciliazione famiglia-lavoro retribuito [The gender gap in the division of childcare and the work-family balance]. Psicol. Della Salut. 2017, 2, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasio, D.; Serri, F.; De Simone, S.; Putzu, D. Il genere e il carico familiare. Il contributo della psicologia discorsiva per una ricerca «rilevante» [Gender and family load. The contribution of discursive psychology to «relevant» research]. Psicol. Soc. 2013, 8, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- De Simone, S.; Pileri, J.; Rapp-Ricciardi, M.; Barbieri, B. Gender and Entrepreneurship in pandemic time: What demands and what resources? An exploratory study. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 668875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Example References | Sample | Methodology | Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women Entrepreneurs | Quantitative | Conflict | |

| Women Entrepreneurs | Quantitative | Work-Family Interface, Enrichment | |

| Mumpreneur, Women Entrepreneurs | Mixed/Qualitative | Studies in which Guilt emerges in entrepreneurship |

| M | SD | Reliability | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Conflict | 2.79 | 0.921 | α = 0.840 | |||||

| 2. Guilt WIF | 3.54 | 1.03 | α = 0.738 | 0.273 ** | ||||

| 3. Guilt FIW | 2.16 | 0.975 | α = 0.832 | 0.583 *** | 0.403 *** | |||

| 4. Enrichment | 4.26 | 1.18 | α = 0.879 | −0.543 *** | −0.587 *** | −0.534 *** | ||

| 5. Job Satisfaction | 3.44 | 0.955 | α = 0.760 | −0.271 *** | −0.321 *** | −0.641 *** | 0.259 *** | |

| 6. Life Satisfaction | 7.34 | 0.885 | −0.513 *** | −0.555 *** | −0.726 *** | 0.631 *** | 0.674 *** |

| Regression Equation | Model | Significance of Regression Coefficients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Predictor(s) | R | R2 | F | Coeff | t | LLCI | ULCI | p |

| Guilt FIW | Conflict | 0.307 | 0.094 | 16.627 | 0.2839 | 8.3208 | 0.1464 | 0.4213 | 0.0001 |

| Guilt WIF | Conflict | 0.679 | 0.462 | 136.581 | 0.6364 | 11.6868 | 0.5289 | 0.7440 | 0.0000 |

| Job Satisfaction | Conflict | 0.743 | 0.552 | 64.636 | −0.6144 | −8.6509 | −0.7547 | −0.4741 | 0.0000 |

| Guilt FIW | −0.4266 | −7.2701 | −0.5425 | −0.3107 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Guilt WIF | −0.1728 | −2.3041 | 0.3210 | 0.0247 | 0.0225 | ||||

| Life Satisfaction | Conflict | 0.795 | 0.633 | 90.3906 | −0.6018 | −5.9685 | −0.8010 | −0.4026 | 0.0000 |

| Guilt FIW | −0.5884 | −7.0625 | −0.7529 | −0.4238 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Guilt WIF | −0.4132 | −3.8796 | −0.6235 | −0.2028 | 0.0002 | ||||

| Regression Equation | Model | Significance of Regression Coefficients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Predictors | R | R2 | F | Coeff | t | LLCI | ULCI | p |

| Guilt FIW | Conflict | 0.60 | 0.36 | 30.04 | 0.2359 | 2.6746 | 0.0617 | 0.4101 | 0.0083 |

| Enrichment | −0.4259 | −6.3300 | −0.5588 | −0.2930 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Int | −0.1296 | −2.5739 | −0.2291 | −0.0302 | 0.0110 | ||||

| Guilt WIF | Conflict | 0.73 | 0.54 | 61.49 | 0.6149 | 8.0749 | 0.4645 | 0.7653 | 0.0000 |

| Enrichment | −0.2554 | −4.3967 | −0.3701 | −0.1407 | 0.0000 | ||||

| Int | 0.1782 | 4.0990 | 0.0923 | 0.2641 | 0.0001 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Simone, S.; Pileri, J.; Mondo, M.; Rapp-Ricciardi, M.; Barbieri, B. Mea Culpa! The Role of Guilt in the Work-Life Interface and Satisfaction of Women Entrepreneur. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710781

De Simone S, Pileri J, Mondo M, Rapp-Ricciardi M, Barbieri B. Mea Culpa! The Role of Guilt in the Work-Life Interface and Satisfaction of Women Entrepreneur. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710781

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Simone, Silvia, Jessica Pileri, Marina Mondo, Max Rapp-Ricciardi, and Barbara Barbieri. 2022. "Mea Culpa! The Role of Guilt in the Work-Life Interface and Satisfaction of Women Entrepreneur" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710781

APA StyleDe Simone, S., Pileri, J., Mondo, M., Rapp-Ricciardi, M., & Barbieri, B. (2022). Mea Culpa! The Role of Guilt in the Work-Life Interface and Satisfaction of Women Entrepreneur. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10781. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710781