Understanding Feedback for Learners in Interprofessional Settings: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Question

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

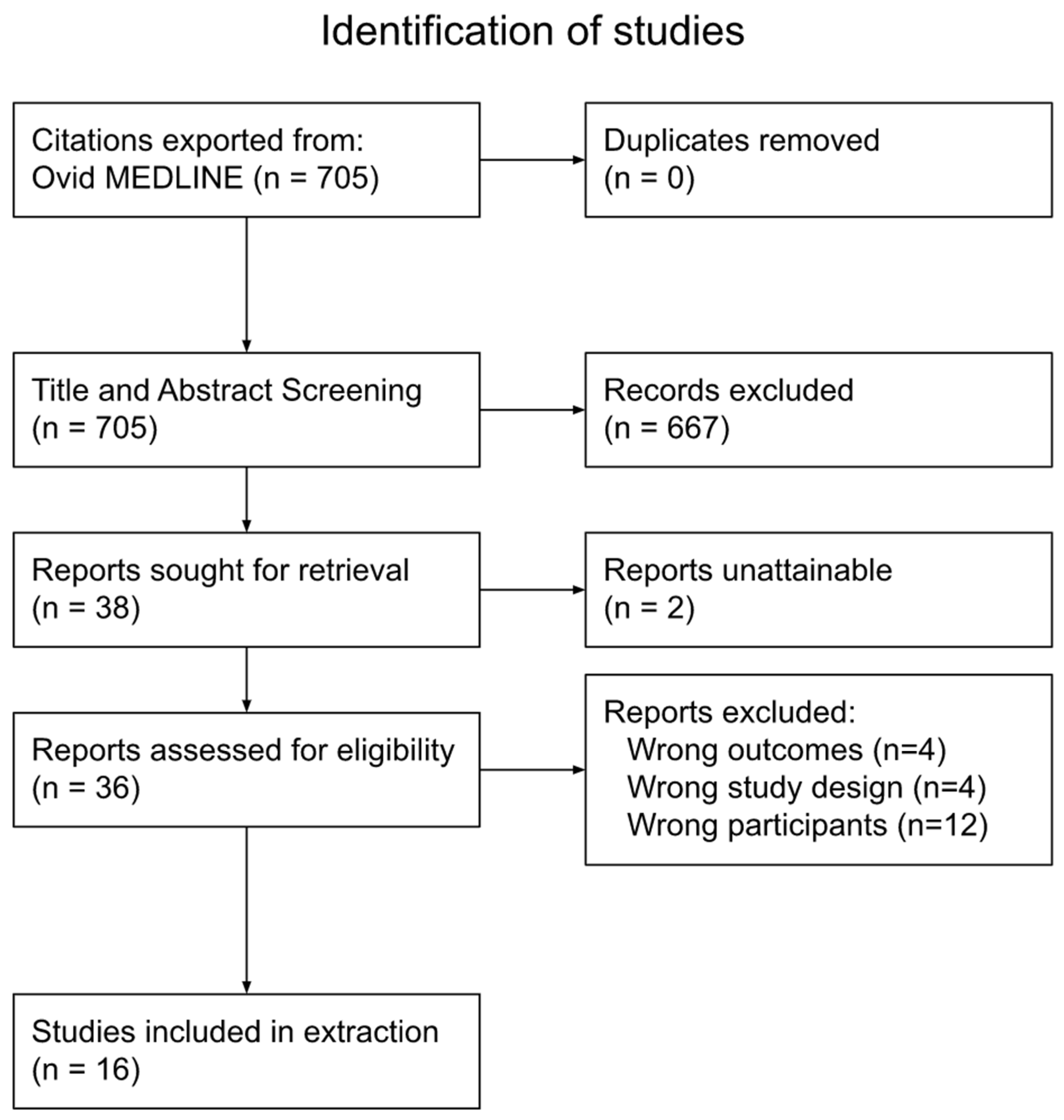

2.4. Screening

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Literature Characteristics

3.2. Key Concepts

3.2.1. Issues with the Feedback Process and the Need for Training

3.2.2. Perception of the Feedback Provider Affects How the Feedback Is Utilized

3.2.3. Professions of the Feedback Provider Affect the Feedback Process

3.2.4. Learners’ Own Attitude toward Feedback Can Affect the Feedback Process

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Main Findings

4.2. Discussion of Findings

4.3. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Search Number | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| 1 | exp Education, Medical/ |

| 2 | medical education.mp. |

| 3 | undergraduate medical education.mp. |

| 4 | student.mp. |

| 5 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 |

| 6 | exp Operations Research/ |

| 7 | feedback.mp. |

| 8 | feed back.mp. |

| 9 | feedback literacy.mp. |

| 10 | 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 |

| 11 | exp Interprofessional Relations/ |

| 12 | Interprofessional.mp. |

| 13 | Interprofessional relations.mp. |

| 14 | Inter professional |

| 15 | 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 |

| 16 | 5 and 10 and 15 |

| 17 | Limit 16 to (year = “2001–Current” and English) |

| Study Details | Study Objective | Study Population | Methodology | Relevant Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tanaka et al. [14] 2017 United States | The study had three main objectives: (1) to determine what constitutes optimal feedback by conducting focus groups of anesthesia students, (2) to develop and test a web-based feedback tool and (3) to map the content of the feedback-tool’s comments | 37 residents | The study used qualitative methods. Residents were invited to participate in one of five focus groups and completed written surveys that assessed their previous feedback experiences. | The focus groups revealed that there were three major barriers to good feedback: feedback that is too late to the point that it is not useful because the residents were not able to learn from feedback because it was too delayed; feedback was not specific and too general, leaving learners unable to effectively use the feedback to improve; and there were too many feedback evaluations that resulted in the feedback being unhelpful. | The study may not be generalizable to other residency institutions, as it was limited to one institution. Additionally, the study did not adequately address additional factors to the feedback process, such as fear, retention and how residents view their environment in terms of psychological safety. |

| Vesel et al. [15] 2016 Canada | The objective was to examine residents’ perceptions and experiences of interprofessional feedback. | 131 residents (15 participated in the interviews) | The study used a mixed-methods approach. A 12-item survey about the frequency of feedback from different professionals and its value was completed by residents. After the survey, the residents were invited for a follow-up interview wherein open-ended questions about residents’ experiences, perceptions and differences with interprofessional feedback were asked. Additionally, questions about suggestions to improve interprofessional feedback were also asked in the interview. | In total, 80% of residents reported receiving written feedback only from physicians (intra-professional) and were more likely to act on said feedback. A total of 26% of residents reported receiving written feedback from nurses, and 10% reported receiving feedback from other professions. According to the qualitative results, 10 themes were found that can be broken up into three topics areas. The first topic area focused on the overall attitude toward interprofessional feedback and established that residents found interprofessional feedback to be an important element; however, they reported receiving very limited feedback from other professions that was often informal and not structured. The second topic area focused on the value of in-group versus outgroup feedback, finding that residents often preferred feedback from physicians (in-group). To the residents, physicians had a better understanding of residents’ expectations and often focused on feedback that residents perceived as more valuable. The third area focused on barriers to interprofessional feedback. Residents often found feedback to be suboptimal across all professions and not of the best quality. They also recognize that effective feedback often requires training. | Although the study included multiple residency programs, it was a single-center study, and this may limit the generalizability of the findings. The response rate to the survey was moderate, with only 52% of eligible residents completing the survey; this may cause the findings to be incomplete. |

| Gran et al. [16] 2016 Norway | The objective was to explore general practitioners’ (GP) and medical students’ experiences with giving and receiving supervision and feedback. | 21 GPs and 9 medical students | The study was an explorative qualitative study. Two interview guides were prepared, with the one for the GPs being aimed at exploring their views and experiences with giving feedback and any potential barriers in the feedback-giving process. The interview guide for students focused on what kind of feedback they view as useful, the students’ role in the feedback process and what conditions promoted useful feedback. Two focus-group interviews were conducted for the GPs, and two focus group interviews were conducted for the students. | GPs first established mutual trust by becoming familiarized with the students’ competency levels and expectations. After this trust was established, the GPs would encourage students to be independent, while being available for supervision and feedback. The students and GPs both agreed that good feedback, which promotes learners’ professional development, was timely, constructive, encouraging and focused on ways to improve. GPs reported that giving feedback on sensitive topics such as body language, focusing on electronic devices, social or language skills, was difficult. Additionally, limited time was another barrier to giving good feedback. | Participants were recruited through the snowball-sampling method, which can cause participants with similar experiences to be included. Additionally, the members of the recruited sample were all from the same university, and this can limit the generalizability of the findings. |

| Van Schaik et al. [17] 2016 United States | The objective was to explore the perceptions of interprofessional peer feedback among health professionals after a team exercise. | 109 medicine students (82 accessed survey and 71 completed survey), 68 pharmacy students (44 accessed survey and 41 completed survey), 59 nursing students (43 accessed survey and 40 completed survey), 49 dentistry students (25 accessed served and 24 completed survey), 16 social-work students (11 accessed survey and 9 completed survey) and 10 dietetics students (9 accessed survey and 9 completed survey) | The study was a prospective cohort study. IP learners participated in the Interprofessional Standardized Patient Exercise that was team-based and early in clinical training. After the exercise, each learner wrote anonymous feedback for each other. After giving the feedback, the students were immediately asked the level to which they agree to the statement that “Giving feedback to the students on my team from other professions was challenging”. Additionally, an online survey was completed by the learners in which they rated the usefulness and positivity of the feedback. | Overall, interprofessional learners rated giving feedback as moderately challenging. Learners found feedback to be both positive and useful. The profession of the feedback provider had no main effect. Additionally, there were no significant interactions between the professions of the feedback recipient and the feedback provider. However, there were significant effects with certain recipient professions’ rating on positivity of feedback, with certain professions (physical therapy) rating positivity higher and certain professions rating positivity lower (dental students). | The response rate was not ideal, as almost one-third of students did not access or rate the feedback they received. Additionally, the study focused on learners in the early years of their education; thus, those learners might not have had much exposure to or experience with other professions and working as a team. |

| Noble et al. [18] 2019 Australia | The objective was to understand the problem with student feedback literacy in the healthcare setting from the perspective of the learner. | 27 healthcare students | The study used qualitative methods, using a social-constructivist approach. Learners underwent feedback-literacy programs and were subsequently interviewed to understand the learners’ perception and experiences of engaging with feedback. The interviews focused on feedback encounters. | From the framework analysis, two themes emerged: (1) the reconceptualization of feedback by learners and (2) learners’ situated engagement in workplace feedback. Following the literacy program, the students reassessed feedback as something they could engage in and not have to wait for. The students also noted that their conversations of feedback lead to plans of improvement that they could actively engage in. A challenging aspect that remained for students was being able to reconcile these new understandings of feedback in busy clinical settings. | Students’ experiences may be affected by recall accuracy. Additionally, the transferability of the findings may be limited due to the study having taken place in one hospital. |

| Van Hell et al. [19] 2009 Netherlands | The objective was to find empirical evidence to prove that the supervisor’s role, observation of behavior and learners’ active participation are important factors in valuable feedback. | 142 medical students | The study was performed through quantitative methods. Students on the clinical rotations recorded factors surrounding each feedback event that happened to them. This included answering the following questions: Who provided the feedback? Was the feedback based on observation of behavior? Who initiated the feedback moment? What was the perceived instructiveness of the feedback? | Perceived feedback instructiveness from residents and specialists was similar but still more instructive than feedback from nurses. Feedback on directly observable behavior was reported to be more instructive than feedback on behaviors that were not directly observed. Feedback from learners’ own initiative was found to be more instructive than feedback from a supervisor’s initiative. | The number of events when feedback was given was relatively low. Furthermore, the study may be limited by demographics, particularly gender, as 78% of participants were women. Additionally, the “perceived instructiveness” variable may not represent the educational value it intended to measure due to its being based on students’ experiences. |

| Bowen et al. [20] 2017 United Kingdom | The objective was to explore medical students’ beliefs about feedback and how their perceptions were reflected by their feedback behaviors. | 25 medical students | The study used a qualitative approach based on grounded theory. Five focus groups that contained 4–6 students each were used to analyze the learners’ perceptions of feedback in regard to the learner–educator relationship. A feedback map was used as a tool to evaluate the engagement of learners. | The three feedback behaviors that emerged are recognizing, using and seeking feedback. Influencing these behaviors are five core themes: learners’ beliefs, attitudes and perceptions; relationships; teacher attribute; mode of feedback; and learning culture. Learning culture was found to have an impact within all three feedback behaviors. | The study focused on a relatively small sample from a single institution, thus limiting generalizability. |

| Crommelinck and Anseel [21] 2013 | The objective was to review the literature on feedback-seeking behavior in order to provide practical recommendations to educators on how to encourage such behavior. | No study population but focused on interprofessional medical settings | This study was a review of the literature (qualitative). They first defined feedback-seeking behavior and its consequences, and then they discussed various aspects and backgrounds of feedback-seeking behavior. They continued to identify issues that are unresolved in the literature. Finally, in response to the issues, they presented the self-motives framework that serves as a more comprehensive framework for understanding feedback-seeking behaviors. | Feedback-seeking behavior has inherent value in aiding in the adaption, socialization, learning, creativity and performance of learners. There are several individual and contextual factors that influence this behavior, including learning-goal orientation, public versus private environments and leadership styles. Firstly, there is higher instrumental value to feedback when oriented learners have learning goals. These learners also view failure as a way to increase effort, making them less afraid of negative feedback. Additionally, learners were found to be less likely to seek feedback when they are observed by others compared to private settings. Finally, learners tend to have higher intentions for seeking feedback from their supervisor if they view them as transformational leaders. Based on the review, the authors present six recommendations: (1) encourage learners that have low performance expectations to seek feedback so that they can learn and normalize errors and mistakes as a normal aspect of learning; (2) encourage feedback seeking during periods when there are newcomers in socialization events; (3) provide sufficient feedback; (4) train learners to develop learning-goal orientations; (5) use technology and communication to encourage feedback seeking and provide opportunities to privately seek feedback; and (6) train leaders in a variety of strategies that can encourage feedback-seeking behavior | The authors did not discuss limitations in their review of the literature. They simply discussed the findings based on a self-motives’ framework. |

| Teunissen et al. [22] 2009 Netherlands | The objective was to determine what sorts of variables influence feedback-seeking behaviors for residents on night shifts. | 166 residents | This study was performed by using quantitative methods. Residents were sent a questionnaire that assessed four predictor variables, two mediator variables and two outcome variables. The predictor variables were learning and performance-goal orientation, and instrumental and supportive leadership. The mediator variables were perceived feedback benefits and cost. The outcome variables were frequency of feedback inquiry and monitoring. | Residents who perceived more feedback benefits were found to report a higher frequency of feedback inquiry and monitoring (taking in self-relevant information from the environment by observation of others). Additionally, those who perceive more feedback costs result in more feedback monitoring. Those who have a higher learning-goal orientation perceive more feedback benefits with lower costs. Importantly, supportive teachers (physicians) lead residents to perceive more feedback benefits and fewer costs. | Some of the variables of the study such as the “feedback benefits” variable may not be representative of the actual concept. The study also focused on one field of residents in night shifts, thus limiting generalizability. |

| Bok et al. [23] 2013 Netherlands | The objective was to explore the feedback-seeking behaviors of learners in a clinical setting. | 14 veterinary medical students | The study was an explorative qualitative study. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with year-5 and year-6 veterinary medical students. The interview’s structure was based on the theoretical aspects of feedback-seeking behavior. The interview used questions that focused on students’ goals and motives in seeking feedback, characteristics of their feedback-seeking behavior and various factors that influence this behavior. | The interviews showed that there are personal and interpersonal factors that influence feedback-seeking behavior. Personal factors depend on the intentions of the learner, characteristics of the learner and characteristics of the feedback provider. Interpersonal factors include the relationship between the learner and the feedback provider. The analysis also showed three factors that can influence feedback-seeking behavior: ego, image and perceived benefit. Students are motivated to seek feedback that gives them positive judgments of their competence and avoid negative feedback. Those with learning-goal orientations focused on improving their knowledge and skills through feedback. The personal and interpersonal factors, as well as the potential benefits and negative effects of feedback seeking, gave rise to the feedback seeking behaviors. | The study was conducted in one setting, thus limiting generalizability. Additionally, the focus on veterinary medical education may not transfer to medical education that deals with human patients. Moreover, interview data may not capture the entire picture of feedback-seeking behavior due to the inductive method of data analysis. |

| Telio et al. [24] 2016 Canada | The objective was to examine how learners make credibility judgements on feedback and the consequences of those judgements. | 34 residents (8 residents participated in interviews) | The study was performed by using a constructivist grounded-theory approach. Second- and third-year psychiatry residents were invited to participate. Those who responded to the invitation were asked to complete a feedback questionnaire that addressed the quality and quantity of feedback they received in clinical settings. Additionally, an Educational Alliance Scale (EAS) that focused on the relationship between the resident and the supervisor was also administered. Those with diverse scores were invited for the interviews. Semi-structured interviews were conducted for the eligible participants. The interview data were collected and analyzed to identify themes. | Participants explained that they actively contemplated feedback. They actively considered the feedback they received based on their judgments of their supervisor and their relationship with their supervisor. They were found to make judgements regularly about the supervisor’s clinical credibility during their feedback interactions, as well as the supervisor’s credibility in the education alliance. These judgements resulted in broad-ranging implications that affected the content of the feedback and their future interactions with the supervisor. | The sampling strategy, a limited number of participants and a focus on psychiatry residents may have affected the validity of the results. |

| Feller and Berendonk [25] 2020 Switzerland | The objective was to explore the perspectives of interprofessional feedback in the context of workplace-based assessment. | 7 residents, 7 supervising physicians, and 9 allied healthcare professionals (4 diabetes nurses, 3 nutritionists and 2 psychologists) | The study used a qualitative approach based on grounded theory. Educational sessions on interprofessionalism were conducted and attended by participants. Next, workplace-based assessments were completed by residents under the supervision of supervising physicians and allied healthcare professionals. Feedback from both observers were provided after each assessment. Finally, focus-group discussions with all participants were conducted for data collection. | Four key themes were found: identity and hierarchy; interdependence of feedback source and feedback content; impact on collaboration and patient care; and logistical and organizational requirements. Feedback perceptions on interprofessional sources helped raise awareness of working conditions of other fields and helped improve communication between different groups. Perceptions on intra-professional feedback led to feedback being perceived in a more summative nature. Trustworthiness was viewed as an important factor in the feedback process, more so than professional affiliations. | The study was conducted in a single clinic and had a relatively small sample size, which may not make the results representative. Additionally, anonymity in the study may not have been properly achieved, leading to the modifications of answers. |

| Andrews et al. [26] 2019 Canada | The objective was to explore the perceived value of feedback by dental students on their performance on simulations by either a peer or faculty member. | 126 dental students | The study used quantitative methods. Prior to the study, participants completed an interprofessional education curriculum and an Objective Structured Clinical Examination. Participants were separated into two cohorts, one that was trained in giving feedback and one that was not trained. They were then randomized into two groups: the peer-led group and the faculty-led group. In the groups, pairs viewed a video recording of the student performance in the simulation and responded to a set of reflection questions. The student was instructed to reflect on the question first and then receive input from the faculty or peer evaluator. After the feedback sessions, the groups completed a questionnaire to evaluate their experience. | In both cohorts, students valued the feedback and believed that it improved their skills. The results indicated that learners perceived clear value in participating in peer-led feedback. Despite this, students rated faculty feedback higher than peer feedback. Additionally, the learners in the peer-led group indicated that they found inherent value in the process of giving feedback, as it was a learning experience for them. This value did not differ by gender, age, class year or OSCE performance. | The study took place in a single school, thus limiting generalizability. Additionally, the lack of monitoring on a peer-led feedback group means that there is no way of knowing if students adhered to the instructions. Feedback sessions were not performed immediately after the simulation, and there was a difference in timings between when the peer group had its feedback sessions and when the faculty group had its sessions. This may affect the quality of the feedback received. |

| Brinkman et al. [27] 2007 United States | The objective was to determine if residents’ performance in communication and professional behaviors improved after augmenting the standard feedback on residents’ performance with multisource feedback. | 36 pediatric residents | The study was a randomized control trial. Residents were randomized into either the multisource feedback group or the control group. In the multisource feedback group, residents completed a self-assessment and received a feedback report about parent and nurse evaluations. They also participated in a coaching session in addition to the standard feedback. The control group received only standard feedback. Both groups were evaluated at baseline and after 5 months, where their communication and professional skills were rated by parents and nurses of pediatric patients during the residents’ pediatric rotations. | Baseline characteristics and ratings were similar in nature. For parents, ratings increased for the multisource feedback group compared to the control group; however, the difference was not significant. For nurses, ratings increased for the multisource feedback group but decreased for the control group, with the difference being significant. | The generalizability of the study may be limited due to the focus on one institution. Additionally, the study may be underpowered to determine significant differences on parent ratings. Residents’ awareness of the evaluations may have led to the Hawthorne effect. |

| Van Schaik et al. [28] 2016 United States | The objective was to explore the perceptions of feedback outside of nurses and resident physician’s professional groups. | 25 residents and 25 nurses (20 completed the survey) | The study was a prospective cohort study. A simulated team exercise was undertaken in which pairs of nurses and residents wrote anonymous performance feedback for each participant. Participants were then given a survey where they were asked to rate the feedback on its usefulness, positivity and agreement. Additionally, the participants were randomized into two groups. One group had four feedback comments, with two of the comments labelled with the correct profession that supplied the feedback and the other two labelled incorrectly. The other group had no labels and were asked to guess the profession of the comment’s source. Interactions between the recipient’s profession, the actual feedback provider’s profession and the perceived provider profession were examined. | There was no significant interaction between the actual profession of the feedback provider and the profession of the recipient, meaning that there was no evidence that nurses or physicians gave different ratings depending on the actual professions of the feedback providers. However, the labelling of the feedback was found to have an influence on the ratings, as there were significant interactions between the labelled profession of the feedback provider and the feedback recipient. This means that nurses rated nurse-sourced feedback higher than physician-sourced feedback, and residents rated physician-sourced feedback higher than nurse-sourced feedback. Additionally, there were significant interactions between the guessed source of feedback and the feedback recipient. Nurses who guessed the feedback came from nurses rated that feedback higher than feedback that was guessed to come from physicians. Similarly, physicians who guessed that the feedback source came from physicians rated the feedback higher than feedback that was guessed to come from nurses. | The study focused only on written feedback, and this could limit the transferability of their findings to other areas of feedback. Additionally, it was a single-center study, which can limit transferability. The study did not consider other demographic factors, such as gender and age, and this could affect feedback. Moreover, it is possible that the written feedback which was provided is not representative of the actual feedback provided in the workplace, outside of the study. |

| Miles et al. [29] 2020 Canada | The objective was to explore the perceptions of feedback providers and learners in order to understand how interprofessional feedback is formed, delivered, received and used. | 17 residents, 11 rehab therapists, 8 social workers, 16 nurses, and 9 pharmacists | The study used the constructivist grounded-theory methodology. Individual interviews were conducted with residents, and focus groups were conducted with the other health professionals. From this, themes were identified. | The themes that captured how residents perceived feedback from health professionals and how these potential feedback providers perceive their role are as follows: the conceptualization and content of the feedback were dependent on the interprofessional relationship; perceptions of professional identity are what shape the validity of feedback; and the enactment of feedback is influenced by power and hierarchy. Feedback was found to be influenced by power differences, and residents were found to value feedback from physicians more so than from other health professionals. | The study was limited to only one institution, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. |

References

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. 2010. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative. A National Interprofessional Competency Framework. 2010. Available online: https://phabc.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/CIHC-National-Interprofessional-Competency-Framework.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: Report of an Expert Panel. 2011. Available online: https://www.aacom.org/docs/default-source/insideome/ccrpt05-10-11.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2022).

- Van De Ridder, J.M.M.; Stokking, K.M.; McGaghie, W.C.; Cate, O.T. What is feedback in clinical education? Med. Educ. 2008, 42, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, J.C. State of the science in health professional education: Effective feedback. Med. Educ. 2010, 44, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hattie, J.; Timperley, H. The Power of Feedback. Rev. Educ. Res. 2007, 77, 81–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfe, I.E.; Sanson-Fisher, R.W. Translating learning principles into practice: A new strategy for learning clinical skills. Med. Educ. 2002, 36, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohn, L.T.; Corrigan, J.; Donaldson, M.S. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. 2000. Available online: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/9728.html (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Bing-You, R.G.; Trowbridge, R.L. Why Medical Educators May Be Failing at Feedback. JAMA 2009, 302, 1330–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watling, C.J.; Lingard, L. Toward meaningful evaluation of medical trainees: The influence of participants’ perceptions of the process. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. Theory Pract. 2012, 17, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Tanaka, P.; Bereknyei Merrell, S.; Walker, K.; Zocca, J.; Scotto, L.; Bogetz, A.L.; Macario, A. Implementation of a Needs-Based, Online Feedback Tool for Anesthesia Residents with Subsequent Mapping of the Feedback to the ACGME Milestones. Anesthesia Analg. 2017, 124, 627–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesel, T.P.; O’Brien, B.C.; Henry, D.M.; van Schaik, S.M. Useful but Different: Resident Physician Perceptions of Interprofessional Feedback. Teach. Learn. Med. 2016, 28, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gran, S.F.; Brænd, A.M.; Lindbæk, M.; Frich, J.C. General practitioners’ and students’ experiences with feedback during a six-week clerkship in general practice: A qualitative study. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2016, 34, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schaik, S.M.; Regehr, G.; Eva, K.W.; Irby, D.M.; O’Sullivan, P.S. Perceptions of Peer-to-Peer Interprofessional Feedback Among Students in the Health Professions. Acad. Med. 2016, 91, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, C.; Billett, S.; Armit, L.; Collier, L.; Hilder, J.; Sly, C.; Molloy, E. “It’s yours to take”: Generating learner feedback literacy in the workplace. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2020, 25, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hell, E.A.; Kuks, J.B.M.; Raat, A.N.; Van Lohuizen, M.T.; Cohen-Schotanus, J. Instructiveness of feedback during clerkships: Influence of supervisor, observation and student initiative. Med. Teach. 2009, 31, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, L.; Marshall, M.; Murdoch-Eaton, D. Medical Student Perceptions of Feedback and Feedback Behaviors within the Context of the “Educational Alliance”. Acad. Med. 2017, 92, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crommelinck, M.; Anseel, F. Understanding and encouraging feedback-seeking behaviour: A literature review. Med. Educ. 2013, 47, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, P.W.; Stapel, D.A.; van der Vleuten, C.; Scherpbier, A.; Boor, K.; Scheele, F. Who Wants Feedback? An Investigation of the Variables Influencing Residents’ Feedback-Seeking Behavior in Relation to Night Shifts. Acad. Med. 2009, 84, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bok, H.G.J.; Teunissen, P.W.; Spruijt, A.; Fokkema, J.P.I.; van Beukelen, P.; Jaarsma, D.A.D.C.; Van Der Vleuten, C.P.M. Clarifying students’ feedback-seeking behaviour in clinical clerkships. Med. Educ. 2013, 47, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telio, S.; Regehr, G.; Ajjawi, R. Feedback and the educational alliance: Examining credibility judgements and their consequences. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 933–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, K.; Berendonk, C. Identity matters—Perceptions of inter-professional feedback in the context of workplace-based assessment in Diabetology training: A qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andrews, E.; Dickter, D.N.; Stielstra, S.; Pape, G.; Aston, S.J. Comparison of Dental Students’ Perceived Value of Faculty vs. Peer Feedback on Non-Technical Clinical Competency Assessments. J. Dent. Educ. 2019, 83, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkman, W.B.; Geraghty, S.R.; Lanphear, B.P.; Khoury, J.C.; Gonzalez del Rey, J.A.; DeWitt, T.G.; Britto, M.T. Effect of Multisource Feedback on Resident Communication Skills and Professionalism: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schaik, S.M.; O’Sullivan, P.S.; Eva, K.W.; Irby, D.M.; Regehr, G. Does source matter? Nurses’ and Physicians’ perceptions of interprofessional feedback. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miles, A.; Ginsburg, S.; Sibbald, M.; Tavares, W.; Watling, C.; Stroud, L. Feedback from health professionals in postgraduate medical education: Influence of interprofessional relationship, identity and power. Med. Educ. 2021, 55, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D.; Boud, D. The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 1315–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjawi, R.; Molloy, E.; Bearman, M.; Rees, C.E. Contextual influences on feedback practices: An ecological perspective. In Scaling up Assessment for Learning in Higher Education; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 7, pp. 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Oakes, P.J.; Haslam, S.A.; McGarty, C. Self and Collective: Cognition and Social Context. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1994, 20, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, B. Group processes in medical education: Learning from social identity theory. Med. Educ. 2012, 46, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coelho, V.; Scott, A.; Bilgic, E.; Keuhl, A.; Sibbald, M. Understanding Feedback for Learners in Interprofessional Settings: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710732

Coelho V, Scott A, Bilgic E, Keuhl A, Sibbald M. Understanding Feedback for Learners in Interprofessional Settings: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710732

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoelho, Varun, Andrew Scott, Elif Bilgic, Amy Keuhl, and Matthew Sibbald. 2022. "Understanding Feedback for Learners in Interprofessional Settings: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710732

APA StyleCoelho, V., Scott, A., Bilgic, E., Keuhl, A., & Sibbald, M. (2022). Understanding Feedback for Learners in Interprofessional Settings: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10732. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710732