Primary Care Physicians’ Perceptions on Nurses’ Shared Responsibility for Quality of Patient Care: A Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Study Population

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Characteristics

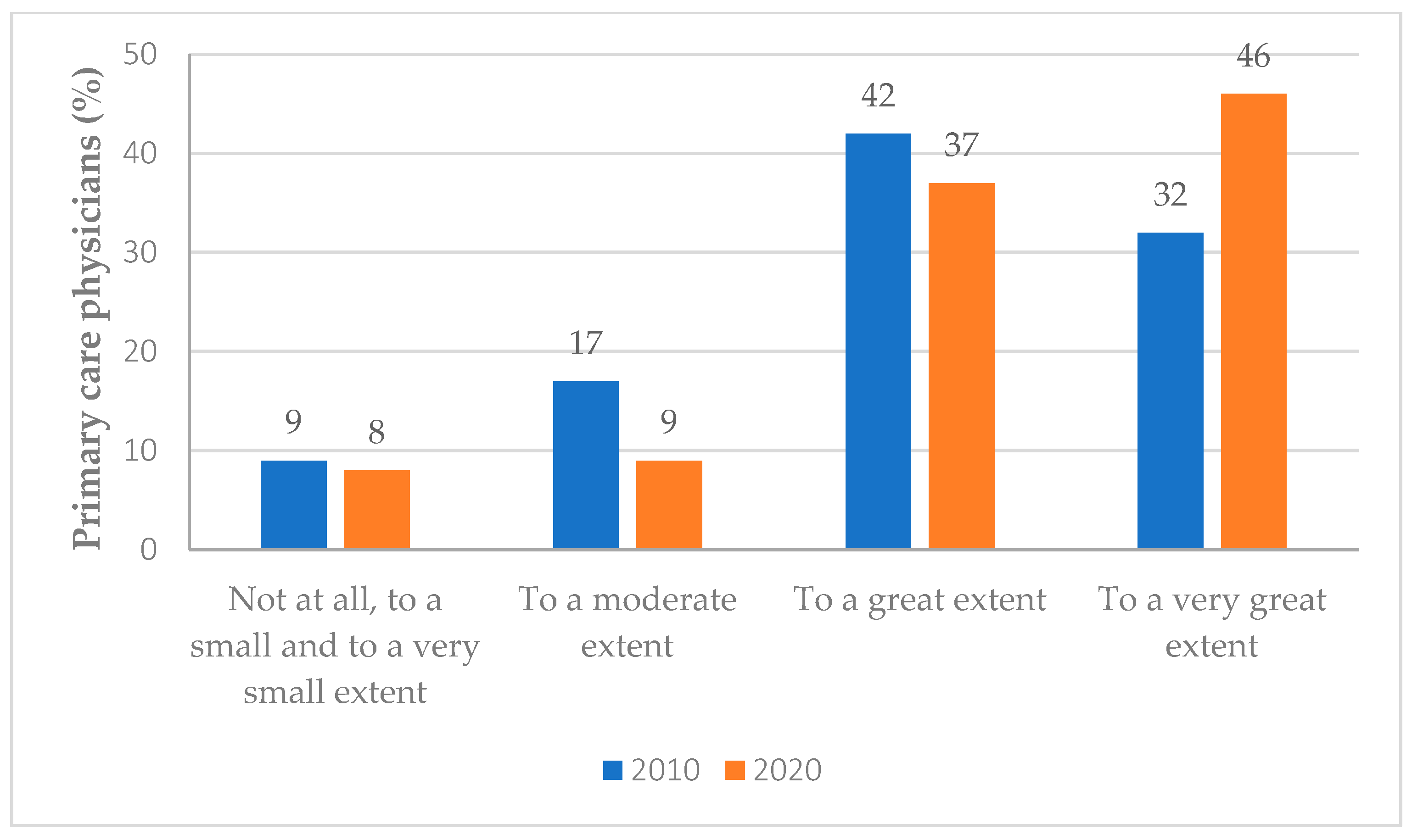

3.2. PCPs’ Perceptions on Nurses’ Shared Responsibility for the Improvement of Quality-of-Care

3.3. PCPs’ Perceptions on the Contribution of Nurses’ Actual Involvement to the Quality of Practice

3.4. Independent Predictors of PCPs’ Perceptions Regarding Nurses’ Responsibility for the Improvement of Quality-of-Care

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nissanholtz-Gannot, R.; Rosen, B.; The Quality Monitoring Study Group. Monitoring quality in Israeli primary care: The primary care physicians’ perspective. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2012, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nissanholtz-Gannot, R.; Goldman, D.; Rosen, B.; Kay, C.; Wilf-Miron, R. How Do Primary Care Physicians Perceive the Role of Nurses in Quality Measurement and Improvement? The Israeli Story. Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarfield, A.M.; Manor, O.; Nun, G.B.; Shvarts, S.; Azzam, Z.S.; Afek, A.; Basis, F.; Israeli, A. Health and health care in Israel: An introduction. Lancet 2017, 389, 2503–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.; Waitzberg, R.; Merkur, S. Israel: Health System Review. Health Syst. Transit. 2015, 17, 1–212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rosen, B. How Health Plans in Israel Manage the Care Provided by Their Physicians; Smokler Center for Health Policy Research, Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute Jerusalem: Jerusalem, Israel, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IMA. Israel Medical Association Position Paper to the Committee of Health Minister MK Yael German Committee, to Strengthen the Public Healthcare System; Israel Medical Association: Ramat Gan, Israel, 2013.

- Johnson, J.E. Working together in the best interest of patients. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2013, 26, 241–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Pullon, S.; Morgan, S.; Macdonald, L.; McKinlay, E.; Gray, B. Observation of interprofessional collaboration in primary care practice: A multiple case study. J. Interprof. Care 2016, 30, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadewaldt, V.; McInnes, E.; Hiller, J.E.; Gardner, A. Views and experiences of nurse practitioners and medical practitioners with collaborative practice in primary health care—An integrative review. BMC Fam. Pract. 2013, 14, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, A.; de Lusignan, S.; Rowlands, G. Do primary care professionals work as a team: A qualitative study. J. Interprof. Care 2005, 19, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, S.J.; Parchman, M.L.; Fuda, K.K.; Schaefer, J.; Levin, J.; Hunt, M.; Ricciardi, R. A review of instruments to measure interprofessional team-based primary care. J. Interprof. Care 2016, 30, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.M.; McDonald, K.M.; Shojania, K.G.; Sundaram, V.; Nayak, S.; Lewis, R.; Owens, D.K.; Goldstein, M.K. Quality improvement strategies for hypertension management: A systematic review. Med. Care 2006, 44, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Júnior, L.C. Advanced Practice Nursing and the Expansion of the Role of Nurses in Primary Health Care in the Americas. SAGE Open Nurs. 2021, 7, 23779608211019491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. State of the World’s Nursing; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Peterson, L.E.; Phillips, R.L.; Puffer, J.C.; Bazemore, A.; Petterson, S. Most family physicians work routinely with nurse practitioners, physician assistants, or certified nurse midwives. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2013, 26, 244–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualano, M.R.; Bert, F.; Adige, V.; Thomas, R.; Scozzari, G.; Siliquini, R. Attitudes of medical doctors and nurses towards the role of the nurses in the primary care unit in Italy. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2018, 19, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schottle, D.; Schimmelmann, B.G.; Karow, A.; Ruppelt, F.; Sauerbier, A.L.; Bussopulos, A.; Frieling, M.; Golks, D.; Kerstan, A.; Nika, E.; et al. Effectiveness of integrated care including therapeutic assertive community treatment in severe schizophrenia spectrum and bipolar I disorders: The 24-month follow-up ACCESS II study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2014, 75, 1371–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmond, S.W.; Echevarria, M. Healthcare Transformation and Changing Roles for Nursing. Orthop. Nurs. 2017, 36, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, M.; Wong, S.T.; Martin-Misener, R.; Browne, A.J. The role of registered nurses in primary care and public health collaboration: A scoping review. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriarte-Roteta, A.; Lopez-Dicastillo, O.; Mujika, A.; Ruiz-Zaldibar, C.; Hernantes, N.; Bermejo-Martins, E.; Pumar-Méndez, M.J. Nurses’ role in health promotion and prevention: A critical interpretive synthesis. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3937–3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurant, M.; van der Biezen, M.; Wijers, N.; Watananirun, K.; Kontopantelis, E.; van Vught, A.J. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, CD001271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierick-van Daele, A.T.; Metsemakers, J.F.; Derckx, E.W.; Spreeuwenberg, C.; Vrijhoef, H.J. Nurse practitioners substituting for general practitioners: Randomized controlled trial. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissanholtz-Gannot, R.; Rosen, B.; Hirschfeld, M.; Shapiro, Y. Changes in the community nurse′s work. Soc. Secur. 2016, 99, 121–147. [Google Scholar]

- Juraschek, S.P.; Zhang, X.; Ranganathan, V.; Lin, V.W. United States Registered Nurse Workforce Report Card and Shortage Forecast. Am. J. Med. Qual. 2019, 34, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drennan, V.M.; Ross, F. Global nurse shortages-the facts, the impact and action for change. Br. Med. Bull. 2019, 130, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manojlovich, M.; DeCicco, B. Healthy work environments, nurse-physician communication, and patients′ outcomes. Am. J. Crit. Care 2007, 16, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, A.B. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J. Ky. Med. Assoc. 2007, 105, 165–169. [Google Scholar]

- Baggs, J.G.; Schmitt, M.H.; Mushlin, A.I.; Mitchell, P.H.; Eldredge, D.H.; Oakes, D.; Hutson, A.D. Association between nurse-physician collaboration and patient outcomes in three intensive care units. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 27, 1991–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraeder, C.; Shelton, P.; Sager, M. The effects of a collaborative model of primary care on the mortality and hospital use of community-dwelling older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, M106–M112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogstad, U.; Hofoss, D.; Hjortdahl, P. Doctor and nurse perception of inter-professional co-operation in hospitals. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2004, 16, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.T.; Doran, D.M.; Tourangeau, A.E.; Fleshner, N.E. Perceived quality of interprofessional interactions between physicians and nurses in oncology outpatient clinics. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Oglio, I.; Rosati, G.V.; Biagioli, V.; Tiozzo, E.; Gawronski, O.; Ricci, R.; Garofalo, A.; Piga, S.; Gramaccioni, S.; Di Maria, C.; et al. Pediatric nurses in pediatricians′ offices: A survey for primary care pediatricians. BMC Fam. Pract. 2021, 22, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matziou, V.; Vlahioti, E.; Perdikaris, P.; Matziou, T.; Megapanou, E.; Petsios, K. Physician and nursing perceptions concerning interprofessional communication and collaboration. J. Interprof. Care 2014, 28, 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.S.; Armer, J.M. An inside view. NP/MD perceptions of collaborative practice. Nurs. Health Care Perspect. 2000, 21, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orchard, C.A. Persistent isolationist or collaborator? The nurse′s role in interprofessional collaborative practice. J. Nurs. Manag. 2010, 18, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman-Azuz, N.; Goldstein, R.; Gever, A. Family Medicine—What Has Changed in Expectations and Satisfaction; Israel National Institute For Health Policy Research: Ramat Gan, Israel, 2018.

| Variable | 2010 N = 605 n (%) | 2020 N = 450 n (%) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | <0.001 | ||

| <45 years | 157 (26) | 76 (17) | |

| 45–60 years | 333 (55) | 225 (50) | |

| >60 years | 115 (19) | 149 (33) | |

| Sex | NS | ||

| Female | 226 (44) | 180 (40) | |

| Male | 339 (56) | 270 (60) | |

| Religion | <0.001 | ||

| Jewish | 460 (76) | 320 (71) | |

| Non-Jewish | 145 (24) | 130 (29) | |

| Country of birth | <0.005 | ||

| Israel | 242 (40) | 220 (49) | |

| Other | 363 (60) | 230 (51) | |

| Board certification | NS | ||

| Family medicine | 248 (41) | 158 (35) | |

| Internist | 121 (20) | 99 (22) | |

| Non-specialist | 236 (39) | 193 (43) | |

| Occupation | <0.001 | ||

| Primary care physician | 557 (92) | 396 (88) | |

| Specialist | 48 (8) | 54 (12) | |

| Employment status | NS | ||

| Employed by the health plan | 284 (47) | 189 (42) | |

| Self-employed (independent contractor) | 170 (28) | 171 (38) | |

| Both | 151 (25) | 90 (20) |

| Extent of Involvement | 2010 Weighted % * | 2020 Weighted % * |

|---|---|---|

| To a very great extent | 17 | 25 |

| To a great extent | 42 | 42 |

| To a moderate extent | 26 | 21 |

| To a small extent | 9 | 7 |

| To a very small extent and not at all | 6 | 5 |

| Primary Care Physicians’ Response to Survey Items | Respondents Who Perceived That Nurses Share Responsibility for Quality-of-Care to a Very Great Extent Weighted Percentage * (p-Value) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2020 | |

| Psycho-social state affects medical condition and success of treatment | ||

| To a very great extent | 43 (<0.001) | 52 (<0.001) |

| Follow-up on indicators increases work overload | ||

| To a very great extent | 42 (<0.001) | 46 (<0.001) |

| Time devoted to follow-up and improvement of scores on indicators | ||

| Up to 5% of the time | 34 (<0.001) | 48 (<0.001) |

| Nurses contribute to quality-of-care | ||

| To a very great extent | 78 (<0.001) | 86 (<0.001) |

| Nurses share with me the performance measured | ||

| Definitely agree | 63 (<0.001) | 70 (<0.001) |

| I am responsible for the performance of some indicators and nurses—for others | ||

| Definitely agree | 56 (<0.001) | 64 (<0.001) |

| Variable | Entered as | Reference Group | B | SE B | Odds Ratio | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45–60 | <45 | −0.474 | 0.073 | 0.622 | <0.001 |

| >60 | −0.310 | 0.085 | 0.734 | <0.001 | ||

| Religion | Jewish | Non-Jewish | 0.672 | 0.082 | 1.958 | <0.001 |

| Country of birth | Israel | Other countries | 1.040 | 0.071 | 2.830 | <0.001 |

| Gender | Male | Female | −0.059 | 0.065 | 0.943 | 0.370 |

| Board certification | Family physician | non-certified | −0.228 | 0.068 | 0.796 | <0.001 |

| Internist/other | 0.266 | 0.108 | 1.305 | 0.014 | ||

| Form of employment | Salaried | Self-employed | 0.198 | 0.079 | 1.219 | 0.012 |

| Both salaried and self-employed | 0.261 | 0.089 | 1.298 | 0.003 | ||

| Year of survey | 2020 | 2010 | 0.205 | 0.077 | 1.228 | 0.007 |

| Attitude to follow-up of quality-of-care | Increases work overload to a very high extent | Increases work overload to a low extent | 0.180 | 0.065 | 1.197 | 0.005 |

| Commitment of up to 5% of time to indicators | Commitment of more than 5% of time to indicators | 0.279 | 0.072 | 1.321 | <0.001 | |

| Psycho-social state projects onto medical condition | To a very great extent | To a great extent or less | 0.507 | 0.058 | 1.660 | <0.001 |

| Shared physician-nurse responsibility | Completely agree | Agree or less | 0.321 | 0.068 | 1.379 | <0.001 |

| Full physician-nurse shared responsibility | Completely agree | Agree or less | 1.600 | 0.064 | 4.954 | <0.001 |

| Nurses actually contribute to quality of practice | To a very great extent | To a great extent or less | 1.970 | 0.077 | 7.173 | <0.001 |

| Cox and Snell R2 | 0.28 | |||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.34 | |||||

| N | 1055 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sela, Y.; Artom, T.; Rosen, B.; Nissanholtz-Gannot, R. Primary Care Physicians’ Perceptions on Nurses’ Shared Responsibility for Quality of Patient Care: A Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710730

Sela Y, Artom T, Rosen B, Nissanholtz-Gannot R. Primary Care Physicians’ Perceptions on Nurses’ Shared Responsibility for Quality of Patient Care: A Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710730

Chicago/Turabian StyleSela, Yael, Tamar Artom, Bruce Rosen, and Rachel Nissanholtz-Gannot. 2022. "Primary Care Physicians’ Perceptions on Nurses’ Shared Responsibility for Quality of Patient Care: A Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710730

APA StyleSela, Y., Artom, T., Rosen, B., & Nissanholtz-Gannot, R. (2022). Primary Care Physicians’ Perceptions on Nurses’ Shared Responsibility for Quality of Patient Care: A Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10730. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710730