Adaptation and Validation of the Malay Version of the SAVE-9 Viral Epidemic Anxiety Scale for Healthcare Workers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Research Instruments

2.3.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

2.3.2. SAVE-9 Scale

2.3.3. GAD-7 Scale

2.3.4. PHQ-9 Scale

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Information

3.2. Dimensionality of the SAVE-9 Malay Version

3.3. Reliability and Validity of the SAVE-9 Malay Version

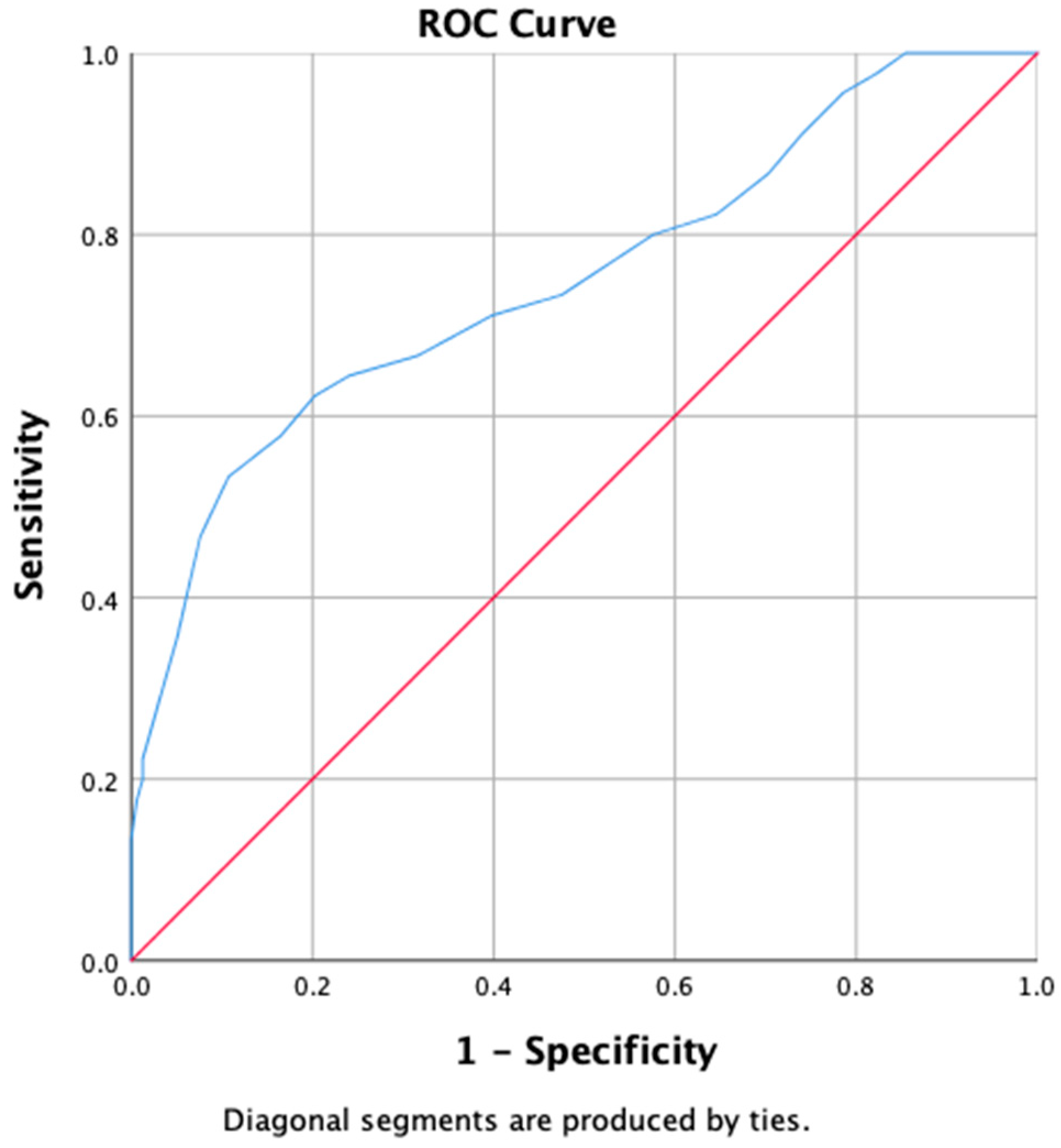

3.4. Cut-Off Score for the SAVE-9 Malay Version

3.5. SAVE-9 Malay Version Scores Based on Anxiety and Depression Levels

4. Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Fifty-Sixth World Health Assembly WHA56.29 Agenda Item 14.16 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Available online: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/documents/health-topics/mers/wha56-29-agenda-item-14-16-sars.pdf?sfvrsn=16254555_8 (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General‘s Statement on IHR Emergency Committee on Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Available online: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-statement-on-ihr-emergency-committee-on-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Subhas, N.; Pang, N.T.-P.; Chua, W.-C.; Kamu, A.; Ho, C.-M.; David, I.S.; Goh, W.W.-L.; Gunasegaran, Y.I.; Tan, K.-A. The Cross-Sectional Relations of COVID-19 Fear and Stress to Psychological Distress among Frontline Healthcare Workers in Selangor, Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kassim, M.A.M.; Pang, N.T.P.; Kamu, A.; Arslan, G.; Mohamed, N.H.; Zainudin, S.P.; Ayu, F.; Ho, C.M. Psychometric properties of the coronavirus stress measure with Malaysian young adults: Association with psychological inflexibility and psychological distress. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hijazi, M.H.A.; Jeffree, M.S.; Pang, N.T.P.; Rahim, S.S.S.A.; Omar, A.; Ahmedy, F.; Hijazi, M.H.A.; Hassan, M.R.; Hod, R.; Nawi, A.M. Seroprevalence of COVID-19 and Psychological Distress among Front Liners at the Universiti Malaysia Sabah Campus during the Third Wave of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelli, I.; Santoro, P.E.; Fiorilli, C.; Angelini, G.; Buonomo, I.; Benevene, P.; Romano, L.; Gualano, M.R.; Amantea, C.; Moscato, U. A new tool to evaluate burnout: The Italian version of the BAT for Italian healthcare workers. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.T.P.; Hadi, N.M.N.; Mohaini, M.I.; Kamu, A.; Ho, C.M.; Koh, E.B.Y.; Loo, J.L.; Theng, D.Q.L.; Wider, W. Factors Contributing to Burnout among Healthcare Workers during COVID-19 in Sabah (East Malaysia). Healthcare 2022, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.-P.; Min, Q.; Gu, W.-W.; Yu, L.; Xiao, X.; Yi, W.-B.; Li, H.-L.; Huang, B.; Li, J.-L.; Dai, Y.-J. Prevalence of mental health problems in frontline healthcare workers after the first outbreak of COVID-19 in China: A cross-sectional study. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, S.; Oetjen, N.; Du, J.; Posenato, E.; De Almeida, R.M.R.; Losada, R.; Ribeiro, O.; Frisardi, V.; Hopper, L.; Rashid, A. Mental health among medical professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic in eight European countries: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woon, L.S.-C.; Sidi, H.; Nik Jaafar, N.R.; Leong Bin Abdullah, M.F.I. Mental health status of university healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A post–movement lockdown assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Imani, V.; Saffari, M.; Griffiths, M.D.; Pakpour, A.H. The fear of COVID-19 scale: Development and initial validation. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.T.P.; Kamu, A.; Hambali, N.L.B.; Mun, H.C.; Kassim, M.A.; Mohamed, N.H.; Ayu, F.; Rahim, S.S.S.A.; Omar, A.; Jeffree, M.S. Malay version of the fear of COVID-19 scale: Validity and reliability. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 20, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.-Y.; Wang, W.-C.; Hsieh, W.-C.; Lee, C.-Y.; Chiu, N.-M.; Yeh, W.-C.; Huang, T.-L.; Wen, J.-K.; Chen, C.-L. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. Br. J. Psychiatry 2004, 185, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Kang, W.S.; Cho, A.-R.; Kim, T.; Park, J.K. Psychological impact of the 2015 MERS outbreak on hospital workers and quarantined hemodialysis patients. Compr. Psychiatry 2018, 87, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, S.; Kim, H.J.; Ahn, M.H.; Yeo, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.; Kang, S.; Suh, S.; Shin, Y.-W. Development of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) Scale for Assessing Work-related Stress and Anxiety in Healthcare Workers in Response to Viral Epidemics. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosolova, E.; Chung, S.; Sosin, D.; Mosolov, S. Stress and anxiety among healthcare workers associated with COVID-19 pandemic in Russia. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavormina, G.; Tavormina, M.G.M.; Franza, F.; Aldi, G.; Amici, P.; Amorosi, M.; Anzallo, C.; Cervone, A.; Costa, D.; D’Errico, I. A new rating scale (SAVE-9) to demonstrate the stress and anxiety in the healthcare workers during the COVID-19 viral epidemic. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okajima, I.; Chung, S.; Suh, S. Validation of the Japanese version of Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) and relationship among stress, insomnia, anxiety, and depression in healthcare workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. Sleep Med. 2021, 84, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, J.; Chung, S.; Ertl, V.; Doering, B.K.; Comtesse, H.; Unterhitzenberger, J.; Barke, A. The German translation of the stress and anxiety to viral epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) scale: Results from healthcare workers during the second wave of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, N.; Akça, Ö.F.; Bilgiç, A.; Chung, S. The validity and reliability of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 items Scale in Turkish health care professionals. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Ahn, M.H.; Lee, S.; Kang, S.; Suh, S.; Shin, Y.-W. The Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-6 Items (SAVE-6) Scale: A New Instrument for Assessing the Anxiety Response of General Population to the Viral Epidemic During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 669606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Lee, J.; Ju, G.; Lee, S.; Suh, S.; Chung, S. The Schoolteachers’ Version of the Stress and Anxiety to Viral Epidemics-9 (SAVE-9) Scale for Assessing Stress and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 712670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.-W.; Chung, S.; Ahn, M.H.; Mohan, S.S.R.; Pang, N.T.P. SAVE-9 Scale (Malay-English). Available online: https://osf.io/htkzg (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- VanVoorhis, C.W.; Morgan, B.L. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2007, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R.L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J.B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 1092–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidik, S.M.; Arroll, B.; Goodyear-Smith, F. Validation of the GAD-7 (Malay version) among women attending a primary care clinic in Malaysia. J. Prim. Health Care 2012, 4, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherina, M.; Arroll, B.; Goodyear-Smith, F. Criterion validity of the PHQ-9 (Malay version) in a primary care clinic in Malaysia. Med. J. Malays. 2012, 67, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Yau, E.; Ping, N.; Shoesmith, W.; James, S.; Hadi, N.; Lin, L. The behaviour changes in response to COVID-19 pandemic within Malaysia. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 27, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, N.T.P.; Nold Imon, G.; Johoniki, E.; Mohd Kassim, M.A.; Omar, A.; Syed Abdul Rahim, S.S.; Hayati, F.; Jeffree, M.S.; Ng, J.R. Fear of COVID-19 and COVID-19 stress and association with sociodemographic and psychological process factors in cases under surveillance in a frontline worker population in Borneo. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woon, L.S.-C.; Mansor, N.S.; Mohamad, M.A.; Teoh, S.H.; Leong Bin Abdullah, M.F.I. Quality of life and its predictive factors among healthcare workers after the end of a movement lockdown: The salient roles of COVID-19 stressors, psychological experience, and social support. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-R.; Wang, K.; Yin, L.; Zhao, W.-F.; Xue, Q.; Peng, M.; Min, B.-Q.; Tian, Q.; Leng, H.-X.; Du, J.-L. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother. Psychosom. 2020, 89, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfante, A.; Di Tella, M.; Romeo, A.; Castelli, L. Traumatic stress in healthcare workers during COVID-19 pandemic: A review of the immediate impact. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.; Landry, C.A.; Paluszek, M.M.; Fergus, T.A.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J. COVID stress syndrome: Concept, structure, and correlates. Depress. Anxiety 2020, 37, 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, S.; Biswas, P.; Ghosh, R.; Chatterjee, S.; Dubey, M.J.; Chatterjee, S.; Lahiri, D.; Lavie, C.J. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norhayati, M.N.; Che Yusof, R.; Azman, M.Y. Vicarious traumatization in healthcare providers in response to COVID-19 pandemic in Kelantan, Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, C.; Zappullo, I.; Group, L.; Conson, M. Tendency to worry and fear of mental health during Italy’s COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ping, N.P.T.; Shoesmith, W.D.; James, S.; Hadi, N.M.N.; Yau, E.K.B.; Lin, L.J. Ultra brief psychological interventions for COVID-19 pandemic: Introduction of a locally-adapted brief intervention for mental health and psychosocial support service. Malays. J. Med. Sci. MJMS 2020, 27, 51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pang, N.T.P.; Tio, V.C.S.; AS, B.S.; Tseu, M.W.L.; Shoesmith, W.D.; Abd Rahim, M.A.; Kassim, M. Efficacy of a single-session online ACT-based mindfulness intervention among undergraduates in lockdown amid COVID-19 pandemic. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | The Original English Version | The Malay Version |

|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | Are you afraid the virus outbreak will continue indefinitely? | Adakah anda takut wabak virus akan berterusan selama-lamanya? |

| Item 2 | Are you afraid your health will worsen because of the virus? | Adakah anda takut kesihatan anda akan bertambah teruk kerana virus? |

| Item 3 | Are you worried that you might get infected? | Adakah anda bimbang anda mungkin dijangkiti? |

| Item 4 | Are you more sensitive towards minor physical symptoms than usual? | Adakah anda lebih peka terhadap gejala fizikal yang kecil daripada biasa? |

| Item 5 | Are you worried that others might avoid you even after the infection risk has been minimized? | Adakah anda bimbang bahawa orang lain mungkin mengelakkan anda, walaupun selepas risiko jangkitan telah berkurang? |

| Item 6 | Do you feel skeptical about your job after going through this experience? | Adakah anda merasa ragu-ragu dengan pekerjaan anda setelah melalui pengalaman ini? |

| Item 7 | After this experience, do you think you will avoid treating patients with viral illnesses? | Selepas pengalaman ini, adakah anda fikir anda akan mengelakkan diri daripada merawat pesakit yang disebabkan oleh virus? |

| Item 8 | Do you worry your family or friends may become infected because of you? | Adakah anda bimbang keluarga atau rakan anda mungkin dijangkiti disebabkan anda? |

| Item 9 | Do you think that your colleagues would have more work to do due to your absence from a possible quarantine and might blame you? | Adakah anda fikir rakan sekerja anda mungkin perlu buat lebih banyak kerja kerana ketiadaan anda disebabkan kemungkinan kuarantin dan mungkin akan menyalahkan anda? |

| Variables | N (%), Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | 20–29 | 83 (40.9%) |

| 30–39 | 108 (53.2%) | |

| ≥40 | 12 (5.9%) | |

| Sex | Female | 152 (74.9%) |

| Male | 51 (25.1%) | |

| Marital status | Single | 94 (46.3%) |

| Married | 109 (53.7%) | |

| Healthcare worker | Medical doctor | 114 (56.2%) |

| Staff nurse | 52 (25.6%) | |

| Other healthcare worker | 37 (18.2%) | |

| Years of employment | 10 (10.70) | |

| Have you cared or are you still caring for COVID-19 patients? | Yes | 154 (75.9%) |

| No | 49 (24.1%) | |

| Have you ever been infected with COVID-19 disease and underwent a quarantine process? | Never | 178 (87.7%) |

| Yes | 25 (12.3%) | |

| Have you ever experienced or been treated for depression, anxiety, or insomnia? | Never | 164 (80.8%) |

| Yes | 39 (19.2%) | |

| Do you feel that you are experiencing depression, anxiety, or need help dealing with your current emotions/moods? | No | 144 (70.9%) |

| Yes | 59 (29.1%) |

| Item | Mean | Std. Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis | Coefficient of Variation | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item 1 | 2.18 | 0.95 | 0.018 | 0.046 | 0.438 | 0.872 | |

| Item 2 | 2.00 | 1.04 | −0.123 | −0.275 | 0.522 | 0.803 | |

| Item 3 | 2.40 | 0.97 | −0.088 | −0.496 | 0.405 | 0.760 | |

| Item 4 | 2.20 | 1.05 | −0.208 | −0.469 | 0.479 | 0.632 | |

| Item 5 | 1.53 | 1.08 | 0.180 | −0.740 | 0.703 | 0.520 | |

| Item 6 | 1.17 | 1.19 | 0.774 | −0.251 | 1.020 | 0.699 | |

| Item 7 | 0.64 | 0.98 | 1.557 | 1.952 | 1.538 | 0.627 | |

| Item 8 | 2.87 | 1.00 | −0.724 | 0.150 | 0.348 | 0.518 | |

| Item 9 | 2.23 | 1.22 | −0.327 | −0.708 | 0.547 | 0.425 |

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Item 2 | 0.872 | |

| Item 1 | 0.803 | |

| Item 3 | 0.760 | |

| Item 4 | 0.632 | |

| Item 5 | 0.520 | |

| Item 6 | 0.699 | |

| Item 7 | 0.627 | |

| Item 9 | 0.518 | |

| Item 8 | 0.425 | |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.863 | 0.670 |

| Methods | Psychometric Measure | Result | Suggested Cut-Off |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTT | Internal consistency measure using Cronbach’s alpha | 0.830 | >0.7 |

| Internal consistency measure using McDonald’s omega | 0.827 | >0.7 | |

| Internal consistency measure using greatest lower bound | 0.887 | >0.7 | |

| Test–retest reliability (Malay and original version) | 0.921 ** | See Note | |

| Convergent validity (SAVE-9 scale versus GAD-7 scale-Malay version) | 0.530 ** | See Note | |

| Convergent validity (SAVE-9 scale versus PHQ-9 scale-Malay version) | 0.500 ** | See Note |

| Score of GAD-7 (Malay Version); Mean (SD) | Score of PHQ-9 (Malay Version) Mean (SD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n = 38) | 1–4 (n = 67) | ≥5 (n = 98) | Kruskal–Wallis Test Results | 0 (n = 20) | 1–9 (n = 135) | ≥10 (n = 48) | Kruskal–Wallis Test Results | |

| SAVE-9 total score | 12.24 (5.45) | 15.58 (4.28) | 20.23 (5.95) | H = 49.638, p < 0.001 | 10.30 (5.10) | 16.51 (5.01) | 22.02 (6.13) | H = 48.738, p < 0.001 |

| Factor 1 score | 8.00 (4.15) | 9.45 (2.79) | 11.79 (3.97) | H = 27.797, p < 0.001 | 7.10 (3.40) | 10.02 (3.38) | 12.44 (4.51) | H = 25.196, p < 0.001 |

| Factor 2 score | 4.24 (2.41) | 6.13 (2.43) | 8.45 (3.05) | H = 54.320, p < 0.001 | 3.20 (2.02) | 6.49 (2.62) | 9.58 (2.96) | H = 59.792, p < 0.001 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wasimin, F.S.; Thum, S.C.C.; Tseu, M.W.L.; Kamu, A.; Ho, C.M.; Pang, N.T.P.; Chung, S.; Wider, W. Adaptation and Validation of the Malay Version of the SAVE-9 Viral Epidemic Anxiety Scale for Healthcare Workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710673

Wasimin FS, Thum SCC, Tseu MWL, Kamu A, Ho CM, Pang NTP, Chung S, Wider W. Adaptation and Validation of the Malay Version of the SAVE-9 Viral Epidemic Anxiety Scale for Healthcare Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710673

Chicago/Turabian StyleWasimin, Fatin Syafiqah, Sean Chern Choong Thum, Mathias Wen Leh Tseu, Assis Kamu, Chong Mun Ho, Nicholas Tze Ping Pang, Seockhoon Chung, and Walton Wider. 2022. "Adaptation and Validation of the Malay Version of the SAVE-9 Viral Epidemic Anxiety Scale for Healthcare Workers" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710673

APA StyleWasimin, F. S., Thum, S. C. C., Tseu, M. W. L., Kamu, A., Ho, C. M., Pang, N. T. P., Chung, S., & Wider, W. (2022). Adaptation and Validation of the Malay Version of the SAVE-9 Viral Epidemic Anxiety Scale for Healthcare Workers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10673. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710673