Participatory Action Research for Tackling Distress and Burnout in Young Medical Researchers: Normative Beliefs before and during the Greek Financial Crisis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework and Participatory Action Research

2.2. Setting and Recruitment Processes

2.3. PLA Sessions and Content Analysis

2.4. Ethical Standards

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Profile

3.2. Causes and Normative Beliefs on Distress and Burnout

3.3. Experiences with Mental Health Services, Wishes, Preferences and Perceived Benefits

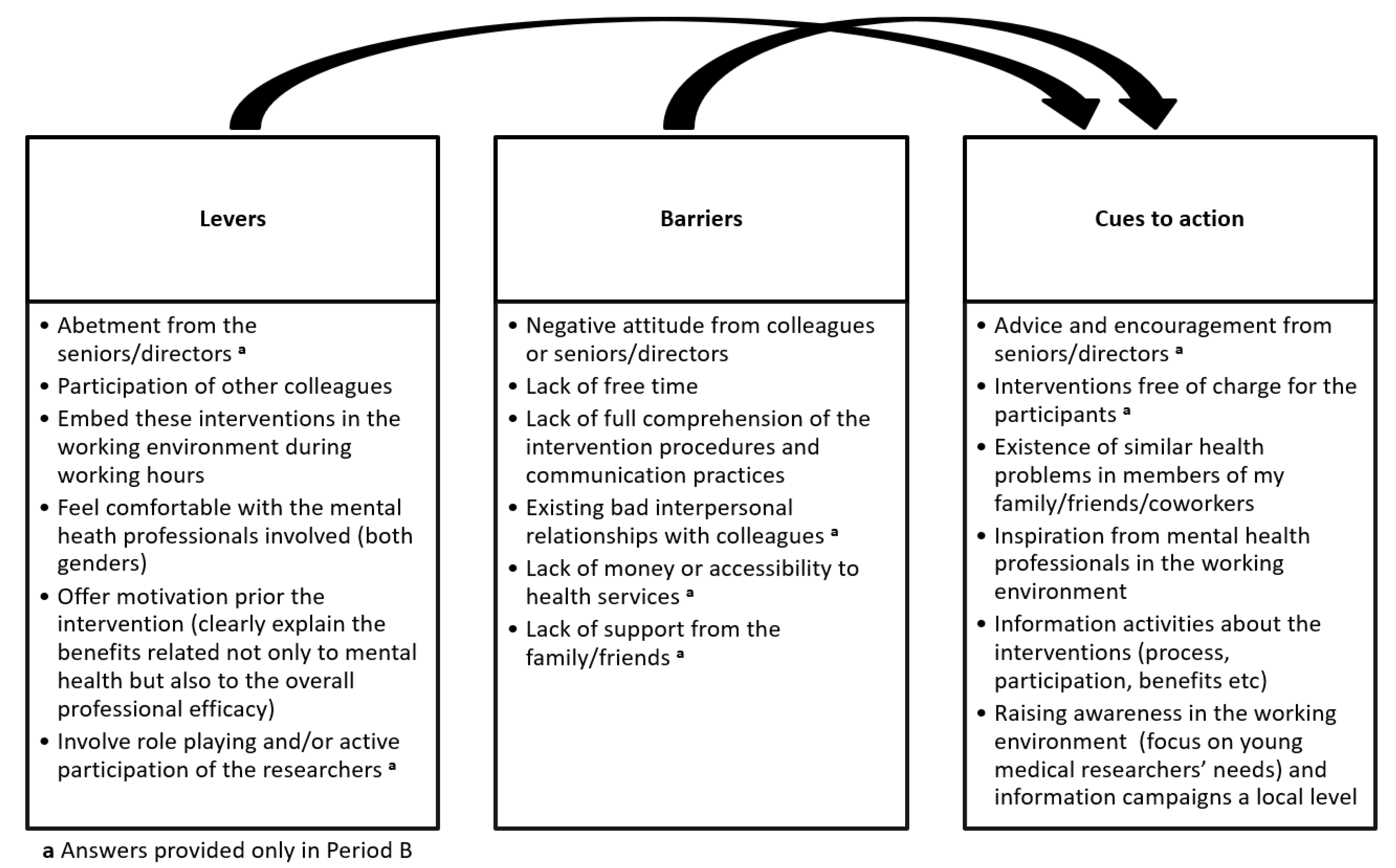

3.4. Levers, Barriers and Cues to Action in Tackling Distress

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Primack, B.A.; Dilmore, T.C.; Switzer, G.E.; Bryce, C.; Seltzer, D.L.; Li, J.; Landsittel, D.P.; Kapoor, W.N.; Rubio, D.M. Brief Report: Burnout Among Early Career Clinical Investigators. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2010, 3, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifaki-Pistolla, D.; Chatzea, V.-E.; Melidoniotis, E.; Mechili, E.-A. Distress and burnout in young medical researchers before and during the Greek austerity measures. Forerunner of a greater crisis? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2018, 53, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabolli, S.; Di Pietro, C.; Renzi, C.; Abeni, D. Job satisfaction and psychological wellbeing in bio-medical researchers. G. Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 2009, 32, B17–B22. [Google Scholar]

- Herbert, D.L.; Coveney, J.; Clarke, P.; Graves, N.; Barnett, A.G. The impact of funding deadlines on personal workloads, stress and family relationships: A qualitative study of Australian researchers. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e004462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linzer, M. Preventing burnout in academic medicine. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 927–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whyte, W.F. Participatory Action Research; Sage Publications Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer, E.; Genat, W. Action Research in Health; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, C.L.; Xu, Y.; Lee, R.; Rose, B.L.; Kappesser, M.; Anthony, J.S. A case study in the use of community-based participatory research in public health nursing. Public Health Nurs. 2006, 23, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwood, D.J.; Levin, M. Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, B. Participatory Action Research, Mental Health Service User Research, and the Hearing (our) Voices Projects. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2012, 11, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branas, C.C.; Kastanaki, A.E.; Michalodimitrakis, M.; Tzougas, J.; Kranioti, E.F.; Theodorakis, P.N.; Carr, B.G.; Wiebe, D.J. The impact of economic austerity and prosperity events on suicide in Greece: A 30-year interrupted time-series analysis. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e005619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frasquilho, D.; Matos, M.G.; Salonna, F.; Guerreiro, D.; Storti, C.C.; Gaspar, T.; Caldas-De-Almeida, J.M. Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: A systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parmar, D.; Stavropoulou, C.; Ioannidis, J.P. Health outcomes during the 2008 financial crisis in Europe: Systematic literature review. BMJ 2016, 354, i4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kentikelenis, A.; Karanikolos, M.; Papanicolas, I.; Basu, S.; McKee, M.; Stuckler, D. Health effects of financial crisis: Omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet 2011, 378, 1457–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drydakis, N. The effect of unemployment on self-reported health and mental health in Greece from 2008 to 2013: A longitudinal study before and during the financial crisis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 128, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Economou, M.; Madianos, M.; Peppou, L.E.; Patelakis, A.; Stefanis, C.N. Major depression in the era of economic crisis: A replication of a cross-sectional study across Greece. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 145, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simou, E.; Koutsogeorgou, E. Effects of the economic crisis on health and healthcare in Greece in the literature from 2009 to 2013: A systematic review. Health Policy 2014, 115, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- May, C.; Finch, T. Implementing, embedding and integrating practices: An outline of normalization process theory. Sociology 2009, 43, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, C.R.; Mair, F.S.; Finch, T.; MacFarlane, A.; Dowrick, C.; Treweek, S.; Rapley, T.; Ballini, L.; Ong, B.N.; Rogers, A.; et al. Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jones, C.L.; Jensen, J.D.; Scherr, C.L.; Brown, N.R.; Christy, K.; Weaver, J. The health belief model as an explanatory framework in communication research: Exploring parallel, serial, and moderated mediation. Health Commun. 2015, 30, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carpenter, C.J. A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of health belief model variables in predicting behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siddiqui, T.R.; Ghazal, S.; Bibi, S.; Ahmed, W.; Sajjad, S.F. Use of the Health Belief Model for the Assessment of Public Knowledge and Household Preventive Practices in Karachi, Pakistan, a Dengue-Endemic City. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0005129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R. The origins and practice of participatory rural appraisal. World Dev. 1994, 22, 953–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munn-Giddings, C.; Hart, C.; Ramon, S. A participatory approach to the promotion of well-being in the workplace: Lessons from empirical research. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2005, 17, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klocker, N. Participatory action research: The distress of (not) making a difference. Emot. Space Soc. 2015, 17, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Reilly-de Brún, M.; de Brún, T.; Okonkwo, E.; Bonsenge-Bokanga, J.-S.; De Almeida Silva, M.M.; Ogbebor, F.; Mierzejewska, A.; Nnadi, L.; van Weel-Baumgarten, E.; van Weel, C.; et al. Using Participatory Learning & Action research to access and engage with ‘hard to reach’ migrants in primary healthcare research. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- May, C.R.; Cummings, A.; Girling, M.; Bracher, M.; Mair, F.S.; May, C.M.; Murray, E.; Myall, M.; Rapley, T.; Finch, T. Using normalization process theory in feasibility studies and process evaluations of complex healthcare interventions: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and Well-Being at the Workplace—Protection and Inclusion in Challenging Times; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- LaMontagne, A.D.; Reavley, N. Workplace Prevention of Mental Health Problems: Guidelines for Organisations; Institute for Safety, Compensation and Recovery Research: Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bonde, J.P. Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: A systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Occup. Environ. Med. 2008, 65, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netterstrøm, B.; Conrad, N.; Bech, P.; Fink, P.; Olsen, O.; Rugulies, R.; Stansfeld, S. The relation between work-related psychosocial factors and the development of depression. Epidemiol. Rev. 2008, 30, 118–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nieuwenhuijsen, K.; Bruinvels, D.; Frings-Dresen, M. Psychosocial work environment and stress-related disorders, a systematic review. Occup. Med. 2010, 60, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ndjaboué, R.; Brisson, C.; Vézina, M. Organisational justice and mental health: A systematic review of prospective studies. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 69, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houdmont, J.; Kerr, R.; Addley, K. Psychosocial factors and economic recession: The Stormont Study. Occup. Med. 2012, 62, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alarcon, G.M. A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2011, 79, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronsson, G.; Theorell, T.; Grape, T.; Hammarström, A.; Hogstedt, C.; Marteinsdottir, I.; Skoog, I.; Träskman-Bendz, L.; Hall, C. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mucci, N.; Giorgi, G.; Roncaioli, M.; Perez, J.F.; Arcangeli, G. The correlation between stress and economic crisis: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2016, 12, 983–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ten Have, M.; Van Dorsselaer, S.; de Graaf, R. The association between type and number of adverse working conditions and mental health during a time of economic crisis (2010–2012). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2015, 50, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.B.; Modini, M.; Joyce, S.; Milligan-Saville, J.S.; Tan, L.; Mykletun, A.; Bryant, R.A.; Christensen, H.; Mitchell, P.B. Can work make you mentally ill? A systematic meta-review of work-related risk factors for common mental health problems. Occup. Environ. Med. 2017, 74, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Kaneyoshi, A.; Yokota, A.; Kawakami, N. Effects of a worker participatory program for improving work environments on job stressors and mental health among workers: A controlled trial. J. Occup. Health 2008, 50, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristics | Period A | Period B |

|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Males | 261 (50.4) | 253 (48.8) |

| Females | 257 (49.6) | 265 (51.2) |

| Age * (years) | 32 (3) | 34 (4) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 261 (50.4) | 284 (54.8) |

| Divorced/Widower | 65 (12.5) | 138 (26.6) |

| Married/Engaged | 192 (37.1) | 96 (18.5) |

| Family members * (individuals) | 2.5 (1) | 1.5 (0.5) |

| Children * (individuals) | 0.5 (0.5) | 2 (0.5) |

| Siblings * (individuals) | 1 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.5) |

| Household status | ||

| Living alone | 238 (35.5) | 134 (25.9) |

| Living with husband/wife/partner | 184 (35.5) | 111 (21.4) |

| Living with family | 81 (15.6) | 176 (34.0) |

| Living with other type of roommate | 15 (2.9) | 97 (18.7) |

| Type of employment | ||

| Permanent | 142 (27.4) | 38 (7.3) |

| Free lancer | 326 (62.9) | 380 (73.4) |

| Volunteer | 50 (9.7) | 100 (19.3) |

| Income * (Euro) | 985 (160) | 535 (90) |

| Working period * (years) | 4.5 (1.5) | 2.5 (1.5) |

| Type of research unit | ||

| University | 265 (51.2) | 280 (54.1) |

| Technical Institution | 253 (48.8) | 238 (45.9) |

| Social activity * (days/week) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (1) |

| Ever smokers | 172 (33.2) | 273 (52.7) |

| Heavy alcohol consumers (≥4 cups/week) | 119 (23.0) | 170 (32.8) |

| Existence of chronic diseases * (number) | 0.5 (0.5) | 3.5 (1) |

| Existence of mental health diseases * (number) | 0.5 (0.5) | 1.5 (1) |

| Distress diagnosis | 54 (10.4) | 196 (37.8) |

| Burnout diagnosis | 112 (21.6) | 303 (58.5) |

| Distress in Period A | Distress in Period B | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Causes | Normative Beliefs | Major Causes | Normative Beliefs |

| Other mental health issues (95%) | Not frequent disease (78%) | Financial issues (98.5%) | Frequent disease (82.5%) |

| Traumatic events (94.5%) | Not serious/can be controlled easily (77%) | High expectations of self and others (85.8%) | Partially serious/can be controlled hardly (82%) |

| Academic pressure (93.5%) | No stigma for others/perceived stigma for themselves (68.5%) | Occupational insecurity (85.5%) | No stigma for others/perceived stigma for themselves (75.6%) |

| Chronic health issues (70%) | Not feeling easily susceptible (65%) | Academic pressure (80.2%) | Feeling very susceptible (75.4%) |

| High expectations of self and others (69%) | Serious impact on everyday life/could be managed by oneself (63.2%) | Family and interpersonal issues (76.4%) | Very serious impact on everyday life/could not be managed by oneself alone (70.9%) |

| Burnout in Period A | Burnout in Period B | ||

| Major Causes | Normative Beliefs | Major Causes | Normative Beliefs |

| Work over hours (62.7%) | Not frequent syndrome (77.5%) | Work over hours (86.4%) | Frequent disease (92%) |

| Academic pressure (61.5%) | Not serious/can be controlled easily (75.3%) | Lack of control and getting stuck in a rut (86%) | Very serious/can be controlled hardly (79.8%) |

| Losing sight of your expectations (59%) | No stigma for others/nor perceived stigma for themselves (62.8%) | Economical barriers and professional insecurity (85.9%) | No stigma for others/nor perceived stigma for themselves (72.1%) |

| Little time to relax and failing to care oneself (58%) | Not feeling easily susceptible (56.2%) | Insufficient rewards (83.2%) | Feeling very susceptible (72%) |

| Bad interpersonal relationships with colleagues (56.5%) | Serious impact on everyday life/could be managed by oneself (51.8%) | Little time to relax and failing to care oneself (82.7%) | Very serious impact on everyday life/could be managed by oneself (69.5%) |

| Period A | ||

|---|---|---|

| Experiences | Wishes/Preferences | Perceived Benefits a |

| Having experience (n = 73; 14.1%) | Willing to participate to participatory intervention (n = 196; 38.4%) | Feeling less distressed and tired |

| Satisfying experience (n = 44; 60.3%) | Willing to organize myself and colleagues to collectively contribute to the work involved in participatory interventions (n = 196; 38.4%) | Feeling stronger and ready to work effectively |

| Experience with participatory interventions (n = 8; 11%) | Jointly with my colleagues build up a shared understanding of the participatory intervention aims (n = 184; 36.1%) | Feeling relived and cheerful |

| Satisfying experience with participatory interventions (n = 8; 100%) | I am ready to sustain and continuously behave in line with a behavioral change intervention (n = 182; 35.7%) | Bond with my colleagues |

| Ready to change risk behaviors (n = 160; 31.4%) | Remember the important things in life (apart from work) | |

| Period B | ||

| Experiences | Wishes/Preferences | Perceived Benefits a |

| Having experience (n = 192; 37.1%) | Willing to participate to participatory intervention (n = 378; 74.1%) | Feeling less distressed, tired and emotionally exhausted |

| Satisfying experience (n = 5; 28.1%) | Willing to organize myself and colleagues to collectively contribute to the work involved in participatory interventions (n = 378; 74.1%) | Feeling being supported by professionals and others |

| Experience with participatory interventions (n = 9; 4.7%) | Jointly with my colleagues build up a shared understanding of the participatory intervention aims (n = 325; 63.7%) | Forget the economical and work-related anxieties |

| Satisfying experience with participatory interventions (n = 9; 100%) | I am ready to sustain and continuously behave in line with a behavioral change intervention (n = 85; 16.7%) | Remember the important things in life (apart from work) |

| Ready to change risk behaviors (n = 76; 15%) | Spend more value time to myself | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sifaki-Pistolla, D.; Mechili, E.A.; Melidoniotis, E.; Argyriadis, A.; Patelarou, E.; Chatzea, V.-E. Participatory Action Research for Tackling Distress and Burnout in Young Medical Researchers: Normative Beliefs before and during the Greek Financial Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710467

Sifaki-Pistolla D, Mechili EA, Melidoniotis E, Argyriadis A, Patelarou E, Chatzea V-E. Participatory Action Research for Tackling Distress and Burnout in Young Medical Researchers: Normative Beliefs before and during the Greek Financial Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710467

Chicago/Turabian StyleSifaki-Pistolla, Dimitra, Enkeleint A. Mechili, Evangelos Melidoniotis, Alexandros Argyriadis, Evridiki Patelarou, and Vasiliki-Eirini Chatzea. 2022. "Participatory Action Research for Tackling Distress and Burnout in Young Medical Researchers: Normative Beliefs before and during the Greek Financial Crisis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710467

APA StyleSifaki-Pistolla, D., Mechili, E. A., Melidoniotis, E., Argyriadis, A., Patelarou, E., & Chatzea, V.-E. (2022). Participatory Action Research for Tackling Distress and Burnout in Young Medical Researchers: Normative Beliefs before and during the Greek Financial Crisis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10467. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710467