Brazilian Strategy for Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Promotion: A Program Impact Pathway Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

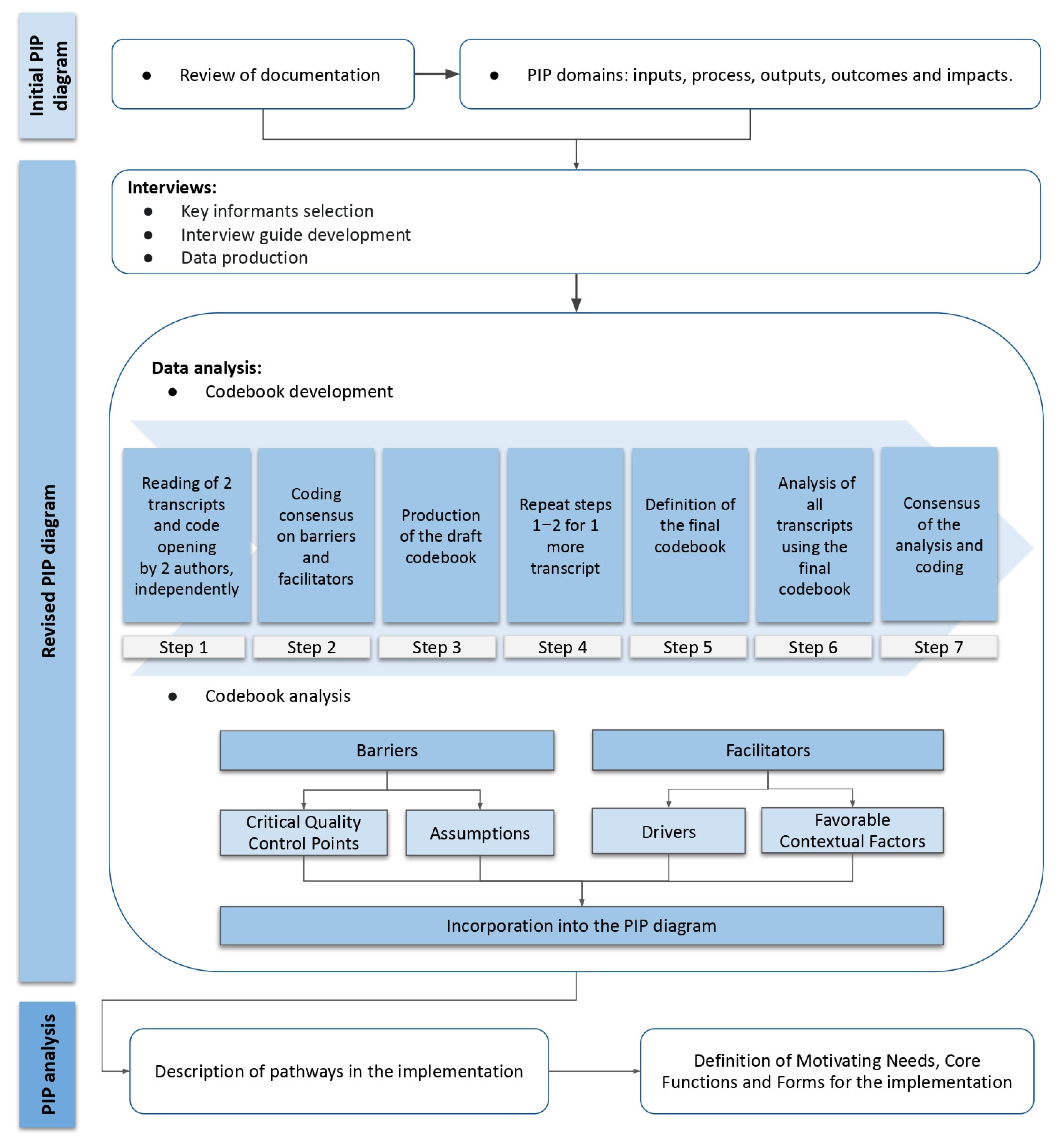

2.1. Initial PIP Diagram

2.1.1. Review of Documentation

2.1.2. PIP Domains

2.2. Revised PIP Diagram

Interviews

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Codebook Development

2.3.2. Codebook Analysis

2.4. PIP Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Initial PIP Diagram

3.2. Revised PIP

3.3. PIP Analysis

3.3.1. Pathway for Financing and Scaling Up the EAAB

3.3.2. Pathway for Improving Professional Skills

3.3.3. Pathways for Certification

3.3.4. Pathways for Monitoring and Evaluating

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization; United Nations Children’s Fund; World Bank Group. Nurturing Care for Early Childhood Development: A Framework for Helping Children Survive and Thrive to Transform Health and Human Potential; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Pietrobelli, A.; Agosti, M.; MeNu Group. Nutrition in the First 1000 Days: Ten Practices to Minimize Obesity Emerging from Published Science. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollins, N.C.; Bhandari, N.; Hajeebhoy, N.; Horton, S.; Lutter, C.K.; Martines, J.C.; Piwoz, E.G.; Richter, L.M.; Victora, C.G.; Lancet Breastfeeding Series Group. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet 2016, 387, 491–504. [Google Scholar]

- Horta, B.L.; de Mola, C.L.; Victora, C.G. Breastfeeding and intelligence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015, 104, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, X.; Wu, H.; Zhao, M.; Magnussen, C.G.; Xi, B. Global prevalence of WHO infant feeding practices in 57 LMICs in 2010–2018 and time trends since 2000 for 44 LMICs. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 37, 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020: Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Prevalence of Feeding Indicators for Children under 5 Years of Age. Brazilian National Survey on Child Nutrition (ENANI-2019). Available online: https://enani.nutricao.ufrj.br/index.php/relatorio-5-alimentacao-complementar/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Venancio, S.I.; Saldiva, S.R.D.M.; Monteiro, C.A. Tendência secular da amamentação no Brasil. Rev. Saúde Pública 2013, 47, 1205–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccolini, C.S.; Boccolini, P.D.M.M.; Monteiro, F.R.; Venâncio, S.I.; Giugliani, E.R.J. Breastfeeding indicators trends in Brazil for three decades. Rev. Saúde Pública 2017, 51, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). Breastfeeding: Prevalence and Practices of Breastfeeding in Brazilian Children under 2 Years of Age. Brazilian National Survey on Child Nutrition (ENANI-2019). Available online: https://enani.nutricao.ufrj.br/index.php/relatorio-4-aleitamento-materno/ (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- McFadden, A.; Siebelt, L.; Marshall, J.L.; Gavine, A.; Girard, L.C.; Symon, A.; MacGillivray, S. Counselling interventions to enable women to initiate and continue breastfeeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Breastfeed. J. 2019, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Improving Young Children’s Diets during the Complementary Feeding Period; UNICEF Programming Guidance; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/media/ (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Colombari, G.C.; Mariusso, M.R.; Ercolin, L.T.; Mazzoleni, S.; Stellini, E.; Ludovichetti, F.S. Relationship between Breastfeeding Difficulties, Ankyloglossia, and Frenotomy: A Literature Review. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021, 22, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relvas, G.R.B.; Buccini, G.; Potvin, L.; Venancio, S. Effectiveness of an Educational Manual to Promote Infant Feeding Practices in Primary Health Care. Food Nutr. Bull. 2019, 40, 544–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Johnston, M.; Lamb, S.E.; et al. Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Estratégia Nacional Para Promoção do Aleitamento Materno e Alimentação Complementar Saudável no Sistema Único de Saúde: Manual de implementação; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2015. Available online: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/estrategia_nacional_promocao_aleitamento_materno.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Establishes the National Strategy for Promotion of Breastfeeding and Healthy Complementary Feeding in the Brazilian Health System (SUS/Brazil); Ministry of Health of Brazil: Brasília, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tomori, C.; Hernández-Cordero, S.; Busath, N.; Menon, P.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. What works to protect, promote and support breastfeeding on a large scale: A review of reviews. Matern. Child Nutr. 2022, 18, e13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, A.S.; Gubert, M.B.; Venancio, S.I.; Buccini, G. Implementation of the Strategy for Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding in the Federal District in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Relatório de gestão 2011–2014: Coordenação-Geral de Alimentação e Nutrição; Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Atenção Básica, Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. Available online: https://aps.saude.gov.br/biblioteca/visualizar/MTQwNQ== (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. e-Gestor. Cobertura da Atenção Básica. MS/SAPS/Departamento de Saúde da Família—DESF. Unidades Geográficas: Brasil. Período: Dezembro de 2020. Available online: https://egestorab.saude.gov.br/paginas/acessoPublico/relatorios/relHistoricoCoberturaAB.xhtml (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Bortolini, G.A.; de Oliveira, T.; da Silva, S.A.; Santin, R.D.C.; de Medeiros, O.L.; Spaniol, A.M.; Pires, A.C.L.; Alves, M.F.M.; Faller, L.D.A. Ações de alimentação e nutrição na atenção primária à saúde no Brasil. Feeding and nutrition efforts in the context of primary healthcare in Brazil. Medidas relativas a la alimentación y la nutrición en la atención primaria de salud en Brasil. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica = Pan Am. J. Public Health 2020, 44, e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccini, G.; Harding, K.L.; Hromi-Fiedler, A.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. How does “Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly” work? A Programme Impact Pathways Analysis. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12766. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Habicht, J.; Menon, P.; Stoltzfus, R.J. How do programs work to improve child nutrition? In Program Impact Pathways of Three Nongovernmental Organization Intervention Projects in the Peruvian Highlands; Discussion Paper; Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division, International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI): Washington, DC, USA, 2011; Available online: http://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/124932/filename/124933.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Buccini, G.; Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Kavle, J.A.; Picolo, M.; Barros, I.; Dillaway, C. Addressing Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding in Nampula, Mozambique: Opportunities to Strengthen Counseling and Use of Job Aids; USAID’s Maternal and Child Survival Program (MCSP): Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.advancingnutrition.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/address_barr_to_excl_bf_in_nampula_mz_opp_to_strengthen_counseling_and_use_of_job_aids.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Elliott, S. Proof of Concept Research. Philos. Sci. 2021, 88, 258–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissemination & Implementation Models in Health Research & Practice. Construct Details. Barriers and Facilitators. Available online: https://dissemination-implementation.org/constructDetails.aspx?id=7 (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Instrutivo Para o Plano de Implantação da Estratégia Amamenta e Alimenta Brasil; Ministry of Health of Brazil: Brasília, Brazil, 2015; Available online: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/documentos/etapas_implantacao_eaab.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Nota Técnica Conjunta N.02/2015—CGSCAM/CGAN/DAPES/DAB/SAS/MS. Nota Técnica sobre o Processo de Certificação da Estratégia Amamenta e Alimenta Brasil para o ano de 2015; Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Ações Programáticas e Estratégicas: Brasília, Brazil, 2015; Available online: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/notas_tecnicas/nota_tecnica_certificacao_EAAB_2015.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Bradley, E.H.; Curry, L.A.; Devers, K.J. Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Serv. Res. 2007, 42, 1758–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos, C.J.G.; Turato, E.R. Content analysis in studies using the clinical-qualitative method: Application and perspectives. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2009, 17, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, H.; Buccini, G.; Curry, L.; Perez-Escamilla, R. The World Health Organization Code and exclusive breastfeeding in China, India, and Vietnam. Matern. Child Nutr. 2019, 15, e12685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safon, C.; Buccini, G.; Ferré, I.; de Cosío, T.G.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Can “Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly” Impact Breastfeeding Protection, Promotion, and Support in Mexico? A Qualitative Study. Food Nutr. Bull. 2018, 39, 393–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolles, M.P.; Lengnick-Hall, R.; Mittman, B.S. Core Functions and Forms of Complex Health Interventions: A Patient-Centered Medical Home Illustration. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buccini, G.; Venancio, S.I.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Scaling up of Brazil’s Criança Feliz early childhood development program: An implementation science analysis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2021, 1497, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez-Escamilla, R.; Sascha, L.; Chris, I.; Susan, A.; Christine, K.; Florence, O. Evaluation of Nigeria’s Community Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling Package, Report of a Mid-Process Assessment; Strengthening Partnerships, Results, and Innovations in Nutrition Globally (SPRING) Project; Nigeria Federal Ministry of Health, and UNICEF: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://www.spring-nutrition.org/sites/default/files/publications/reports/spring_nigeria_c-iycf_mid-process_eval_report_1.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Venancio, S.I.; Martins, M.C.N.; Sanches, M.T.C.; Almeida, H.D.; Rios, G.S.; Frias, P.G.D. Análise de implantação da Rede Amamenta Brasil: Desafios e perspectivas da promoção do aleitamento materno na atenção básica. Cad. Saúde Pública 2013, 29, 2261–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tavares, J.S.; Vieira, D.S.; Dias, T.K.C.; Tacla, M.T.G.M.; Collet, N.; Reichert, A.P.S. Logframe Model as analytical tool for the Brazilian Breastfeeding and Feeding Strategy. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 31, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolini, G.A. Avaliação da Implementação da Estratégia Amamenta e Alimenta Brasil (EAAB); (Especialização em Gestão Pública na Saúde)—Faculdade de Economia, Administração e Contabilidade—FACE, Universidade de Brasília: Brasília, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Hromi-Fiedler, A.J.; Gubert, M.B.; Doucet, K.; Meyers, S.; dos Santos Buccini, G. Becoming Breastfeeding Friendly Index: Development and application for scaling-up breastfeeding programmes globally. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14, e12596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Children’s Fund. UNICEF’s Approach to Digital Health. Health Section Implementation Research and Delivery Science Unit and the Office of Innovation Global Innovation Centre. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/innovation/media/506/file/UNICEF%27s%20Approach%20to%20Digital%20Health%E2%80%8B%E2%80%8B.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Guia Alimentar Para Crianças Brasileiras Menores de 2 Anos; Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção Primaria à Saúde, Departamento de Promoção da Saúde, Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2019.

- WHO. Implementation Guidance: Protecting, Promoting and Supporting Breastfeeding in Facilities Providing Maternity and Newborn Services—The Revised Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Jefferds, M.E.D. Government information systems to monitor complementary feeding programs for young children. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13 (Suppl. 2), e12413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health of Brazil. Atlas da Obesidade Infantil no Brasil; CGAN. DEPROS. SAPS; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2019; Available online: http://189.28.128.100/dab/docs/portaldab/publicacoes/dados_atlas_obesidade.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Bonini, T.P.L.; Lino, C.M.; Sousa, M.L.; Mota, M.J.B.B. Implantação e efeitos da Estratégia Amamenta Alimenta Brasil nas Unidades de Saúde de Piracicaba/SP. Res. Soc. Dev. 2021, 10, e91101421528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEF; WHO. Increasing Commitment to Breastfeeding through Funding and Improved Policies and Programmes—Global Breastfeeding Scorecard. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/ (accessed on 5 September 2021).

- Paina, L.; Peters, D.H. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy Plan. 2012, 27, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Hall Moran, V. Scaling up breastfeeding programmes in a complex adaptive world. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016, 12, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H.; Tucker, A.; Ferguson, O.; Gomes, I.; Dowdy, D. Costing the implementation of public health interventions in resource-limited settings: A conceptual framework. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, G.J.; Buccini, G.S.; Pérez-escamilla, R. Perspective: What Will It Cost to Scale-up Breastfeeding Programs? A Comparison of Current Global Costing Methodologies. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 572–580. [Google Scholar]

| Domain | Operational Definition |

|---|---|

| Inputs | Activities that need to be in place at the federal level to start implementation of the EAAB. |

| Processes | Activities related to coordination at federal, state, and municipal levels, aiming at professional training and implementation monitoring. |

| Outputs | Expected results from the “process” domain activities; mechanisms by which the EAAB affects the IYCF counseling actions in PHC units and provides the implementation certification to PHC units. |

| Outcomes | Final results from the activities in the “process” and “outputs” domains. |

| Impacts | Impacts on the prevalence of BF and CF indicators and results on the nutritional status of children under 2 years old. |

| Critical Quality Control Point | Challenges |

|---|---|

| CCP 1—Definition and strengthening of the coordination in states and municipalities | Lack of political formalization of a municipal coordinator; Lack of a municipal plan for the implementation of the EAAB; Lack of support from coordinators to tutors; Unclear communication between state and municipal coordinators. |

| CCP 2—Maintenance of tutors work. | Difficulty with identifying professionals with an adequate profile and workload availability to be a tutor; The difficulty of tutors maintaining long term work due to overlapping functions and conflict of goals; The difficulty of tutors with providing support to more than one PHC unit. |

| CCP 3—Feasibility of certification process. | Difficulty with achieving four of the six criteria * because of: a high demand for work in PHC units; a high turnover of PHC workers; tutors giving up tutoring PHC units for the long term; only occasional interventions to promote IYCF; a low recording of data on IYCF indicators in the monitoring system. PHC units that do not submit a certification request; Difficulties with organizing the supporting documents necessary to request certification; Instability and lack of integration in the systems; Delayed analysis of requests for certification by the MoH. |

| CCP 4—Quality improvement of IYCF activities in PHC units | Difficulty with keeping PHC workers updated due to a high turnover; A high turnover of tutors, so the training workshops have not continued; Difficulties with fulfilling the certification criteria impacted the quality of activities. |

| CCP 5—Adequate use of monitoring system. | Lack of maintenance of the EAAB implementation monitoring system and the Food and Nutrition Surveillance system (Sisvan); Instabilities in the systems used for data recording and for analyzing certification requests; Lack of detailed information about the activities developed in PHC units to record IYCF in the systems; Low coverage of data about IYCF indicators. |

| CCP 6—Consistent implementation monitoring. | Irregular monitoring of certified PHC units. |

| Assumption for EAAB sustainability | Challenges |

| Specific funding for the implementation of the EAAB | Lack of a specific funding transfer from MoH, states, or municipalities for the implementation of the EAAB; Lack of funding necessary to implement the EAAB, which was a major concern for municipal coordinators. |

| Functional monitoring systems and technical support | Constant instabilities in accessing the monitoring systems; Lack of support on how to use the systems. |

| Periodic evaluation of the EAAB effectiveness and impacts | Lack of monitoring to understand the type of activities carried out in PHC units and their effectiveness; Lack of an official evaluation of the impact on the knowledge and practices of mothers and caregivers on IYCF. |

| Drivers | Opportunities |

|---|---|

| Coordinators have previous experience in IYCF or in the implementation of RAB and ENPACS | Previous work experience with IYCF can positively influence the interest of coordinators regarding the implementation of the EAAB; Previous work experience with the implementation of the Brazilian programs RAB and ENPACS can positively influence the engagement of coordinators with the implementation of the EAAB. |

| Professionals from technical areas of Health Secretariats have good communication | Good communication among professionals from technical areas of the Health Secretariat, such as the Child Health, the Food and Nutrition, and the Primary Health Care, facilitated coordination of the EAAB; Good communication was a driver to prioritize the EAAB in the government plan and to allocate funding to the implementation of the EAAB; The articulation between state coordinators with the regional Health Secretariats facilitated the scaling up of the EAAB to municipalities. |

| Coordinators use resources from the Food and Nutrition Action Financing Program (FAN) | The MoH annually transfers the FAN resources to the states and municipalities; The FAN is designed to fund activities on the Food and Nutrition agenda; The EAAB coordinators can use part of the FAN resources to support the EAAB training workshops. |

| Tutors use the Tutor Support Manual | The use of the EAAB Tutor Support Manual improved the performance of tutors leading complementary training workshops in PHC units; The Tutor Support Manual was developed by Relvas et al. [10] to guide tutors in their activities in PHC units and to give recommendations on how to conduct complementary workshops. |

| Tutors include PHC units’ managers in the planning of EAAB activities | Support from the PHC unit manager to the tutor was crucial for scheduling the training workshops and IYCF interventions; Good results were observed when tutors supported ongoing IYCF counseling activities in PHC units. |

| Coordinators use innovative monitoring strategies | Coordinators who followed tutors more closely through regular meetings improved their work and the implementation of the EAAB; The use of specific monitoring forms helped to collect data on the implementation of the EAAB; The use of the WhatsApp application helped coordinators follow up on tutors’ activities. |

| Coordinators promote the EAAB in Breastfeeding Week events, Municipal Health Council meetings, universities, and seminars | Publicizing the EAAB in events and the municipal Health Council helped PHC units’ managers to learn about the benefits of implementing the EAAB and why they should invest in it. |

| Favorable Contextual Factors | Opportunities |

| EAAB articulation with inter-sectoral policies and initiatives that directly or indirectly support IYCF | The execution of inter-sectoral policies and the integration of education, agriculture, and social assistance in early childhood are important to indirectly support the EAAB; The articulation of the coordination of the EAAB with the Infant Education sector allows developing IYCF activities with kindergarten workers. |

| EAAB articulation with BF supportive sectoral policies and programs | Infant health policies and programs benefited the EAAB actions because they also aimed to improve IYCF; A state law that promotes IYCF supported scaling up of the EAAB; A municipal program to support BF enhanced the communication between the delivery hospitals and the PHC units that implemented EAAB. |

| Development of research on IYCF and policy implementation analysis | The strong scientific evidence supporting IYCF motivates the PHC coordinators to implement the EAAB; Research promoting the use of the EAAB Tutor Support Manual improved tutors’ performance and resulted in positive changes in the activities of PHC units. |

| Motivating Needs | Core Functions | Forms |

|---|---|---|

| Coordination | Presence of coordinators at the three levels of government and in the inter-federative and intra-sectoral articulation | The MoH, the states, and the municipalities appoint professionals from the Health Secretariats to coordinate the EAAB. Professionals from technical areas of Health Secretariats (Food and Nutrition and Child Health) work together at the three government levels to coordinate the EAAB. The municipal Health Secretariats appoint professionals with experience in continuing learning or in the implementation of the Brazilian programs RAB or ENPACS to coordinate the EAAB. |

| Funding and resources | Resource allocation for the implementation of the EAAB | The MoH transfers resources to states and municipalities for the implementation of the EAAB. The MoH transfers resources to states and municipalities through the Food and Nutrition Fund (FAN). States and municipalities use FAN resources for the implementation of the EAAB. States and municipalities allocate their own resources for the implementation of the EAAB. |

| Scaling up the EAAB | Implementation planning across the governmental levels | The MoH makes agreements with states and municipalities to organize the implementation of the EAAB. States select priority regions/municipalities for the implementation of the EAAB based on the nutritional status of children under 2 years old. Municipalities prepare an EAAB implementation plan and define the priority territories/PHC units for the implementation of the EAAB based on the nutritional status of children under 2 years old. Municipal coordinators make inter-sectoral articulations to develop more training workshops. Municipal coordinators support tutors’ agenda to develop training workshops in PHC units. |

| Improvement of professional skills | Establishing a group of national trainers, and training of tutors, and PHC workers | The MoH provides the EAAB Implementation Guide, offers theoretical support materials (e.g., food guide for Brazilian children, the EAAB online course, and the Tutors Support Manual), and establishes a group of national trainers. State coordinators organize the infrastructure and provide human and material resources for the first workshop and the complementary training workshops. State coordinators indicate professionals to work as state trainers to lead more tutor training workshops. National and state trainers lead the tutor training workshops in the state regionals of health and municipalities. Municipal coordinators select professionals to work as tutors and request more tutor training workshops if needed. Municipal coordinators and tutors provide material resources for the development of training workshops in PHC units. PHC workers and managers arrange their schedules to join the training workshop in the PHC unit. Tutors and PHC workers plan a schedule for developing complementary workshops and the EAAB action plan. Tutors follow up on at least one PHC unit and give support to the action plan development. Tutors use the Tutor Support Manual to guide the complementary workshops. |

| Improvement of the work process | Development of activities to obtain the certification | PHC workers systematically develop actions, individually or in groups, to promote IYCF. PHC workers accomplish at least one activity from the action plan. PHC workers record the indicators of IYCF (exclusive BF in children under 6 months old, and CF in children from 6 to 24 months old) in the monitoring system data. PHC workers use a protocol to organize children’s health care. PHC workers comply with NBCAL and Law 11.265/06 and do not distribute milk or infant formulas in PHC units, except for special cases established by law, ordinance, or decree. |

| Impacts on population and implementation sustainability | Implementation monitoring and evaluation | The MoH provides and maintains systems for monitoring the implementation of the EAAB and the IYCF indicators. The MoH systematically monitors and evaluates the implementation of the EAAB. The MoH consults the EAAB trainers and tutors through national surveys and workshops to monitor the implementation quality. State and municipal coordinators monitor the implementation of the EAAB via the system and support tutors’ performance through meetings, events, and other technologies available. Municipal coordinators use supplementary monitoring strategies to control the EAAB monitoring. Municipal and state coordinators provide technical support to tutors and PHC workers on how to use the systems properly. Tutors enter information about the participation of PHC workers in the workshops and their action plan development into the EAAB monitoring system. PHC workers enter data on the IYCF indicators in the system. |

| Social Communication | Dissemination of the EAAB | The MoH publishes the results of the implementation of the EAAB. The MoH provides implementation certification to the PHC units that fulfill the certification criteria. State coordinators host events to promote the EAAB and share experiences about the implementation of the EAAB. Municipal coordinators promote the EAAB in events and in the Health Municipal Committees. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Melo, D.; Venancio, S.; Buccini, G. Brazilian Strategy for Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Promotion: A Program Impact Pathway Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169839

Melo D, Venancio S, Buccini G. Brazilian Strategy for Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Promotion: A Program Impact Pathway Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169839

Chicago/Turabian StyleMelo, Daiane, Sonia Venancio, and Gabriela Buccini. 2022. "Brazilian Strategy for Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Promotion: A Program Impact Pathway Analysis" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169839

APA StyleMelo, D., Venancio, S., & Buccini, G. (2022). Brazilian Strategy for Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding Promotion: A Program Impact Pathway Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9839. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169839