Maternal Competence, Maternal Burnout and Personality Traits in Italian Mothers after the First COVID-19 Lockdown

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Maternal Competence and Burnout

3.3. Correlations between Maternal Neuroticism and Burnout

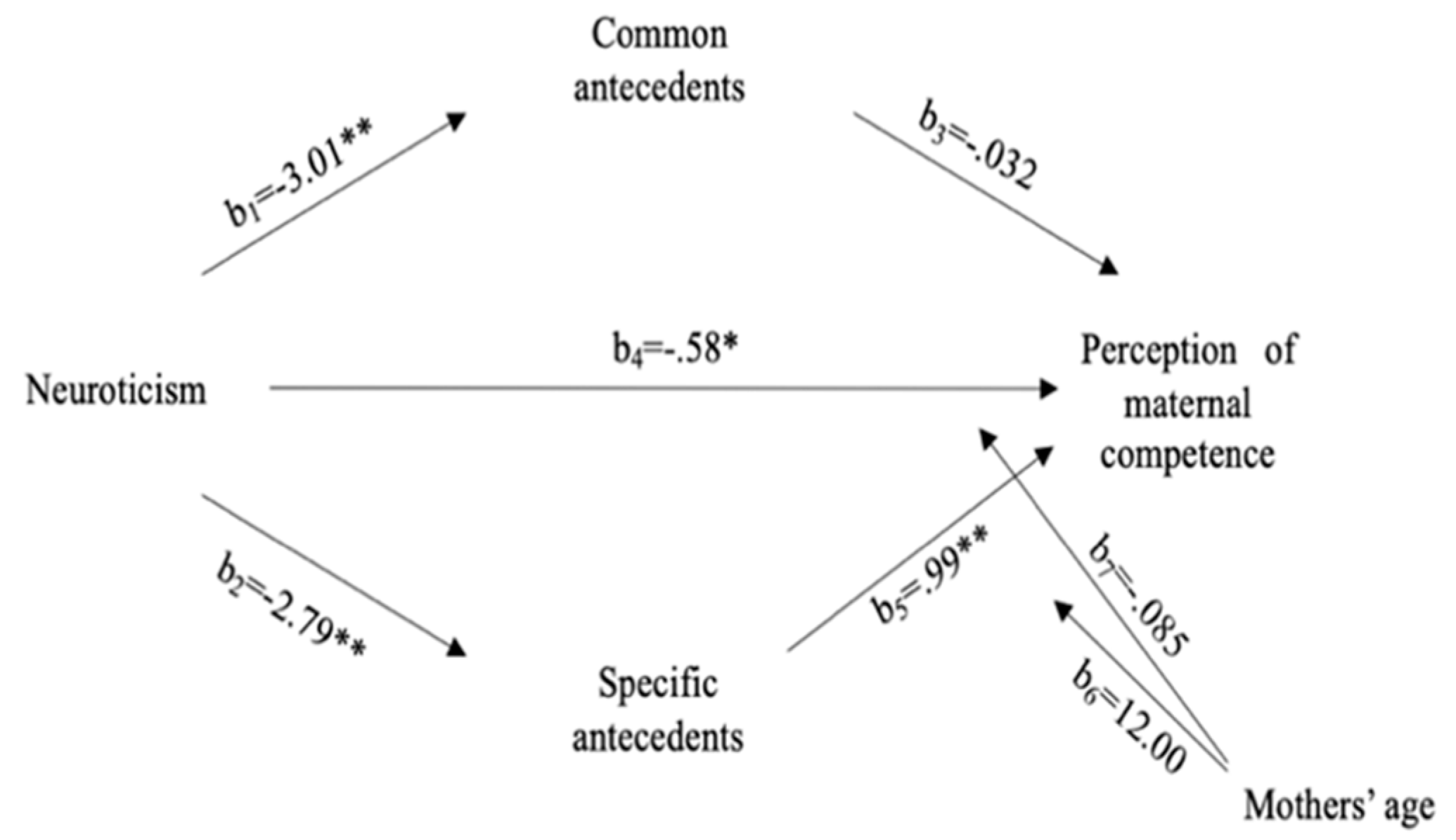

3.4. Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Psychological Support Services

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gassman-Pines, A.; Ananat, E.O.; Fitz-Henley, J. COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics 2020, 146, e2020007294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Vigouroux, S.; Goncalves, A.; Charbonnier, E. The Psychological Vulnerability of French University Students to the COVID-19 Confinement. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 48, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusinato, M.; Iannattone, S.; Spoto, A.; Poli, M.; Moretti, C.; Gatta, M.; Miscioscia, M. Distress, Resilience, and Well-Being in Italian Children and Their Parents during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R. The experience of the 2003 SARS outbreak as a traumatic distress among frontline healthcare workers in Toronto: Lessons learned. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qiu, J.; Shen, B.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, B.; Xu, Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinesepeople in the COVID-19 epidemic: Implication and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 33, e100213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohút, M.; Kohútová, V.; Halama, P. Big Five predictors of pandemic-related behavior and emotions in the first and second COVID-19 pandemic wave in Slovakia. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2021, 180, 110934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caci, B.; Miceli, S.; Scrima, F.; Cardaci, M. Neuroticism and fear of COVID-19. The interplay between boredom, fantasy engagement, and perceived control over time. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury-Jones, C.; Isham, L. The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 2047–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hamza Shuja, K.; Aqeel, M.; Jaffar, A.; Ahmed, A. COVID-19 pandemic and impending global mental health implications. PsychiatrDanub 2020, 32, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, S.H.; Almhdawi, K.; Jaber, A.F.; Alqatarneh, N.S. COVID-19 Quarantine-Related Mental Health Symptoms and their Correlates among Mothers: A Cross Sectional Study. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbers, C.A.; McCollum, C.; Greenwood, E. Physical activity moderates the association between parenting stress and quality of life in working mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ment Health Phys. Act. 2020, 19, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queisser, M.; Adema, W.; Clarke, C. COVID-19, Employment and Women in OECD Countries. 2020. Available online: https://voxeu.org/article/covid-19-employment-and-women-oecd-countries (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Babore, A.; Trumello, C.; Lombardi, L.; Candelori, C.; Chirumbolo, A.; Cattelino, E.; Morelli, M. Mothers’ and Children’s Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown: The Mediating Role of Parenting Stress. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2021, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorkkila, M.; Aunola, K. Risk factors for parental burnout among Finnish parents: The role of socially prescribed perfectionism. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Roskam, I. A Theoretical and Clinical Framework for Parental Burnout: The Balance between Risks and Resources (BR2). Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczak, M.; Gross, J.J.; Roskam, I. Parental burnout: What is it, and why does it matter? Clin. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 7, 1319–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roskam, I.; Raes, M.E.; Mikolajczak, M. Exhausted parents: Development and preliminary validation of the parental burnout inventory. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roskam, I.; Brianda, M.E.; Mikolajczak, M. A step forward in the conceptualization and measurement of parental burnout: The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiverlin, A.; Gallo, A.; Blavier, A. Impact of different kinds of child abuse on sense of parental competence in parents who were abused in childhood. Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2020, 4, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chartier, S.; Delhalle, M.; Baiverlin, A.; Blavier, A. Parental peritraumatic distress and feelings of parental competence in relation to COVID-19 lockdown measures: What is the impact on children’s peritraumatic distress? Eur. J. Trauma Dissociation 2021, 5, 100191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, C.; Aman, J.; Norberg, A.L. Parental burnout in relation to socio-demographic, psychosocial and personality factors as well as disease duration and glycaemic control in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.E.; Joyce, K.M.; Delaquis, C.P.; Reynolds, K.; Protudjer, J.; Roos, L.E. Maternal psychological distress & mental health service use during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 276, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thorsteinsen, K.; Parks-Stamm, E.J.; Kvalø, M.; Olsen, M.; Martiny, S.E. Mothers’ Domestic Responsibilities and Well-Being during the COVID-19 Lockdown: The Moderating Role of Gender Essentialist Beliefs about Parenthood. Sex Roles 2022, 87, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feter, N.; Caputo, E.L.; Doring, I.R.; Leite, J.S.; Cassuriaga, J.; Reichert, F.F.; da Silva, M.C.; Coombes, J.S.; Rombaldi, A.J. Sharp increase in depression and anxiety among Brazilian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from the PAMPA cohort. Public Health 2021, 190, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; Fontanesi, L.; Mazza, C.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Roma, P.; Verrocchio, M.C. Parenting-Related Exhaustion During the Italian COVID-19 Lockdown. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2020, 45, 1114–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, M.; Lionetti, F.; Pastore, M.; Fasolo, M. Parents’ Stress and Children’s Psychological Problems in Families Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C.; Mash, E.J. A measures of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. J. Clin. Child. Psychol. 1989, 18, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vio, C.; Marzocchi, G.; Offredi, F. Il Bambino con Deficit di Attenzione: Iperattività; Diagnosi Psicologica e Formazione dei Genitori; Edizioni Erickson: Trento, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Caci, B.; Cardaci, M.; Tabacchi, M.E.; Scrima, F. Personality variables as predictors of Facebook usage. Psychol. Rep. 2014, 114, 528–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.: Lutz, FL, USA, 1992; Volume 4, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Özdin, S.; Bayrak Özdin, Ş. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchimtchoua Tamo, A.R. An analysis of mother stress before and during COVID-19 pandemic: The case of China. Health Care Women Int. 2020, 41, 1349–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, I.M.; Fernandes, J.; Moura, C.V.; Nobre, P.J.; Carrito, M.L. Adapting to Uncertainty: A Mixed-Method Study on the Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Expectant and Postpartum Women and Men. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 688340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisic, E.; Zalta, A.K.; Van Wesel, F.; Larsen, S.E.; Hafstad, G.S.; Hassanpour, K.; Smid, G.E. Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. BJPsych 2014, 204, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsen, K.; Parks-Stamm, E.J.; Kvalø, K.; Olsen, M.; Martiny. The well-being of Norwegian mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Gender ideologies moderate the relationship between share of domestic work and well-being. Sex Roles 2022, 87, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polizzi, C.; Burgio, S.; Lavanco, G.; Alesi, M. Parental Distress and Perception of Children’s Executive Functioning after the First COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urizar, G.G.; Ramírez, I.; Caicedo, B.I.; Mora, C. Mental health outcomes and experiences of family caregivers of children with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic in Bolivia. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 50, 2682–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, X.; Xue, Q.; Zhu, K.; Wan, Z.; Whu, H.; Zang, J.; Song, R. The prevalence of behavioral problems among school-aged children in home quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic in china. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marčinko, D.; Jakovljević, M.; Jakšić, N.; Bjedov, S.; Mindoljević Drakulić, A. The Importance of Psychodynamic Approach during COVID-19 Pandemic. Psychiatr. Danub. 2020, 32, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Boca, D.; Oggero, N.; Profeta, P.; Rossi, M. Women’s and men’s work, housework and childcare, before and during COVID-19. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2020, 18, 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikčević, A.V.; Marino, C.; Kolubinski, D.C.; Leach, D.; Spada, M.M. Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, R.J.; Ketelaar, T. Personality and susceptibility to positive and negative emotional states. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubert, L.; Crombez, G.; Van Damme, S. The role of neuroticism, pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in vigilance to pain: A structural equations approach. Pain 2004, 107, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, D.; Leaman, C.; Tramposch, R.; Osborne, C.; Liss, M. Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 116, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, R. Personality correlates of the fear of death and dying scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1984, 1, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perricone, G.; Rotolo, I.; Beninati, V.; Billeci, N.; Ilarda, V.; Polizzi, C. The Lègami/Legàmi Service-An Experience of Psychological Intervention in Maternal and Child Care during COVID-19. Pedriatr. Rep. 2021, 13, 142–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S.M.; Rogers, A.A.; Zurcher, J.D.; Stockdale, L.; Booth, M. Does time spent using social media impact mental health?: An eight year longitudinal study. Comput. Human Behav. 2020, 104, 106160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontanesi, L.; Marchetti, D.; Mazza, C.; Di Giandomenico, S.; Roma, P.; Verrocchio, M.C. The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on parents: A call to adopt urgent measures. Psychol. Trauma. 2020, 12, S79–S81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Maternal Competence | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Satisfaction | Efficacy | ||||

| Mother Age | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| <36 (n = 47) | 62.89 (11.16) | F = 1.68 p = 0.18 ηp2 = 0.012 | 35.68 (7.08) | F = 1.30 p = 0.27 ηp2 = 0.009 | 26.20 (8.44) | F = 2.58 p = 0.07 ηp2 = 0.018 |

| 36–45 (n = 151) | 59.98 (11.41) | 33.70 (7.80) | 26.08 (5.82) | |||

| >45 (n = 80) | 59.42 (9.31) | 34.47 (7.06) | 25.35 (5.21) | |||

| Level of education | ||||||

| Primary School (n = 2) | 59.00 (0.00) | F = 2.05 p = 0.06 ηp2 = 0.037 | 30.00 (1.41) | F = 2.179 p = 0.05 * ηp2 = 0.039 | 29.00 (1.41) | F = 11.21 p = 0.30 ηp2 = 0.022 |

| Middle School (n = 17) | 60.94 (7.68) | 34.24 (4.22) | 26.71 (5.91) | |||

| Professional School (n = 19) | 64.79 (11.09) | 36.63 (5.77) | 28.16 (6.94) | |||

| High School (n = 81) | 61.02 (11.35) | 34.51 (7.40) | 26.52 (5.66) | |||

| Degree (n = 114) | 60.61 (10.01) | 34.94 (7.78) | 25.67 (5.58) | |||

| PhD/ Specialization (n = 45) | 56.22 (12.14) | 31.29 (7.98) | 24.93 (5.63) | |||

| Work Regimen during the First Lockdown for COVID-19 | ||||||

| Smart Working (n = 130) | 60.86 (10.03) | F = 1.772 p = 0.13 ηp2 = 0.029 | 33.95 (7.32) | F = 0.965 p = 0.42 ηp2 = 0.016 | 25.17 (5.69) | F = 2.84 p = 0.02 * ηp2 = 0.046 |

| Work at the Workplace (n = 53) | 60.58 (11.06) | 34.34 (7.34) | 26.25 (5.52) | |||

| Suspension of Activities (n = 34) | 60.38 (11.34) | 33.38 (8.15) | 27.00 (5.66) | |||

| Layoffs (n = 12) | 60.58 (12.13) | 36.42 (7.44) | 24.17 (5.73) | |||

| Lost Job (n = 10) | 68.30 (13.62) | 37.80 (9.39) | 30.50 (5.58) | |||

| Child Age | ||||||

| 4–6 (n = 69) | 59.12 (10.77) | F = 1.068 p = 0.36 ηp2 = 0.012 | 32.91 (7.60) | F = 1.06 p = 0.36 ηp2 = 0.011 | 26.20 (5.79) | F = 1.67 p = 0.17 ηp2 = 0.018 |

| 7–10 (n = 93) | 61.72 (11.50) | 34.83 (6.92) | 26.89 (6.27) | |||

| 11–13 (n = 64) | 60.61 (10.56) | 34.86 (8.58) | 25.75 (4.98) | |||

| 14–17 (n =52) | 59.02 (9.93) | 24.73 (5.38) | ||||

| Child Sex | ||||||

| Boys (n = 156) | 61.69 (10.93) | F = 5.86 p = 0.02 * ηp2 = 0.021 | 34.67 (7.53) | F = 1.08 p = 0.29 ηp2 = 0.004 | 27.02 (5.39) | F = 10.41 p = 0.001 ** ηp2 = 0.036 |

| Girls (n = 122) | 58.55 (10.49) | 33.73 (7.41) | 24.82 (5.93) | |||

| Child Atypical Development | ||||||

| Yes (n = 38) Not (n = 240) | 59.32 (10.78) 60.47 (10.85) | F = 0.372 p = 0.54 ηp2 = 0.001 | 34.08 (6.89) 34.29 (7.58) | F = 0.25 p = 0.87 ηp2 = 0.000 | 25.24 (5.54) 26.18 (5.76) | F = 0.893 p = 0.34 ηp2 = 0.003 |

| Parental Burnout | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Common Antecedents | Specific Antecedents | ||||

| Mother Age | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| <36 (n = 50) | 57.68 (61.01) | F = 0.68 p = 0.50 ηp2 = 0.005 | 16.83 (20.95) | F = 1.18 p = 0.30 ηp2 = 0.009 | 40.85 (42.75) | F = 0.394 p = 0.67 ηp2 = 0.003 |

| 36–45 (n = 163) | 57.54 (59.75) | 16.53 (23.01) | 41.01 (39.96) | |||

| >45 (n = 95) | 67.06 (63.70) | 21.26 (23.69) | 45.80 (42.18) | |||

| Level of education | ||||||

| Primary School (n = 2) | 58.50 (57.28) | F = 0.773 p = 0.57 ηp2 = 0.014 | 16.50 (21.92) | F = 0.523 p = 0.75 ηp2 = 0.010 | 42.00 (35.35) | F = 0.882 p = 0.49 ηp2 = 0.016 |

| Middle School (n = 17) | 44.65 (59.11) | 11.76 (18.38) | 32.88 (42.99) | |||

| Professional School (n = 19) | 75.26 (52.28) | 20.21 (18.10) | 55.05 (37.20) | |||

| High School (n = 81) | 57.51 (58.95) | 17.15 (22.76) | 40.36 (40.60) | |||

| Degree (n = 114) | 65.20 (61.42) | 19.84 (23.06) | 45.36 (40.53) | |||

| PhD/ Specialization (n = 45) | 52.60 (68.31) | 16.00 (26.31) | 36.60 (43.91) | |||

| Work Regimen during the First Lockdown for COVID-19 | ||||||

| Smart Working (n = 130) | 60.86 (59.29) | F = 0.476 p = 0.75 ηp2 = 0.008 | 18.77 (21.83) | F = 0.571 p = 0.68 ηp2 = 0.010 | 42.09 (40.02) | F = 0.538 p = 0.70 ηp2 = 0.009 |

| Work at the Workplace (n = 53) | 52.92 (58.31) | 14.74 (22.89) | 38.19 (38.78) | |||

| Suspension of Activities (n = 34) | 61.15 (69.49) | 18.09 (25.68) | 43.06 (46.31) | |||

| Layoffs (n = 12) | 72.25 (52.10) | 24.67 (19.31) | 47.58 (37.82) | |||

| Lost Job (n = 10) | 75.80 (74.14) | 18.10 (25.08) | 57.70 (50.96) | |||

| Child Age | ||||||

| 4–6 (n = 69) | 55.32 (55.34) | F = 0.999 p = 0.39 ηp2 = 0.011 | 14.20 (20.34) | F = 1.45 p = 0.22 ηp2 = 0.016 | 41.12 (37.80) | F = 0.810 p = 0.48 ηp2 = 0.009 |

| 7–10 (n = 93) | 59.52 (58.84) | 18.35 (22.36) | 41.15 (40.27) | |||

| 11–13 (n = 64) | 56.47 (63.98) | 17.36 (23.81) | 39.11 (42.38) | |||

| 14–17 (n = 52) | 73.06 (68.11) | 22.88 (25.45) | 50.17 (44.69) | |||

| Child Sex | ||||||

| Boys (n = 156) | 57.78 (63.39) | F = 0.605 p = 0.43 ηp2 = 0.002 | 16.34 (23.79) | F = 1.74 p = 0.18 ηp2 = 0.006 | 41.44 (42.38) | F = 0.177 p = 0.67 ηp2 = 0.001 |

| Girls (n = 122) | 63.52 (58.02) | 19.99 (21.61) | 43.53 (39.29) | |||

| Child Atypical Development | ||||||

| Yes (n = 38) | 33.55 (68.62) | F = 8.68 p = 0.003 * ηp2 = 0.031 | 6.68 (27.12) | F = 11.03 p = 0.001 ** ηp2 = 0.038 | 26.87 (44.54) | F = 6.408 p = 0.01 * ηp2 = 0.023 |

| Not (n = 240) | 64.54 (58.81) | 19.72 (21.68) | 44.81 (39.95) | |||

| Variables | M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BR2 Tot | 60.30 (61.05) | - | ||||||

| 2. Common Antecedents | 17.94 (22.89) | 0.920 ** | - | |||||

| 3. Specific Antecedents | 42.36 (40.99) | 0.976 ** | 0.811 ** | - | ||||

| 4. Neuroticism | 9.65 (2.95) | −0.281 ** | −0.389 ** | −0.201 ** | - | |||

| 5. Parental Competence | 60.31 (10.83) | 0.349 ** | 0.299 ** | 0.353 ** | −0.209 ** | - | ||

| 6. Satisfaction | 34.26 (7.48) | 0.313 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.303 ** | −0.197 ** | 0.866 ** | - | |

| 7. Efficacy | 26.05 (5.73) | 0.252 ** | 0.184 ** | 0.272 ** | −0.138 * | 0.758 ** | 0.331 ** | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Polizzi, C.; Giordano, G.; Burgio, S.; Lavanco, G.; Alesi, M. Maternal Competence, Maternal Burnout and Personality Traits in Italian Mothers after the First COVID-19 Lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169791

Polizzi C, Giordano G, Burgio S, Lavanco G, Alesi M. Maternal Competence, Maternal Burnout and Personality Traits in Italian Mothers after the First COVID-19 Lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):9791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169791

Chicago/Turabian StylePolizzi, Concetta, Giulia Giordano, Sofia Burgio, Gioacchino Lavanco, and Marianna Alesi. 2022. "Maternal Competence, Maternal Burnout and Personality Traits in Italian Mothers after the First COVID-19 Lockdown" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 9791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169791

APA StylePolizzi, C., Giordano, G., Burgio, S., Lavanco, G., & Alesi, M. (2022). Maternal Competence, Maternal Burnout and Personality Traits in Italian Mothers after the First COVID-19 Lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 9791. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169791