Impacts of the Pandemic, Animal Source Food Retailers’ and Consumers’ Knowledge and Attitudes toward COVID-19, and Their Food Safety Practices in Chiang Mai, Thailand

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

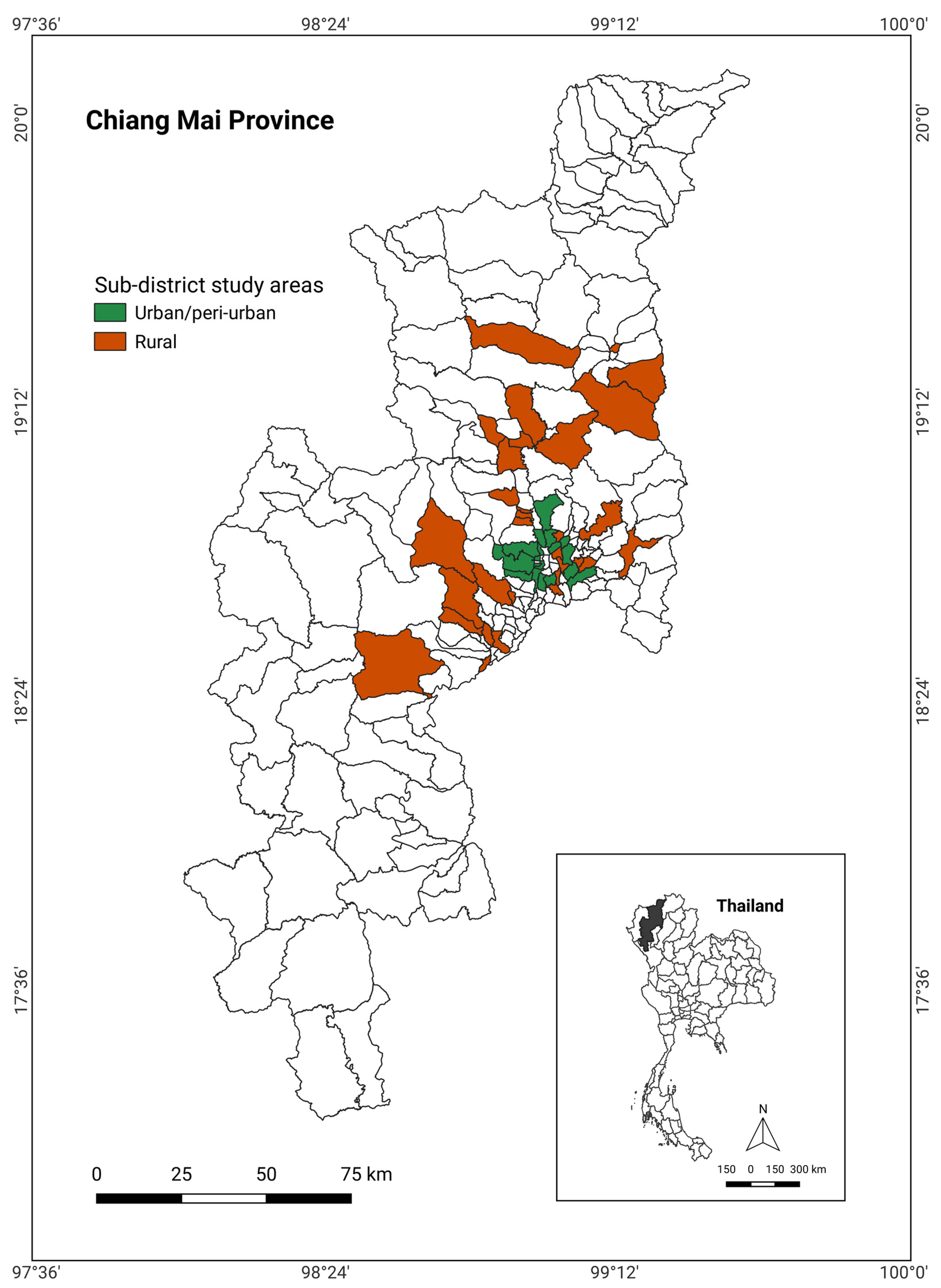

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Design and Sample Size

2.3. Selection Criterion of Participants

2.4. Ethics Statement

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Management and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

3.2. Impacts of COVID-19 to Retailers

3.2.1. Average Amount of ASF Sold at Different Periods

3.2.2. ASF Suppliers

3.2.3. Average Numbers of ASF Shops in the Same Market/Area

3.2.4. Frequency of Selling and ASF Distributions

3.2.5. Labor Resources and Time Spent on Selling ASF

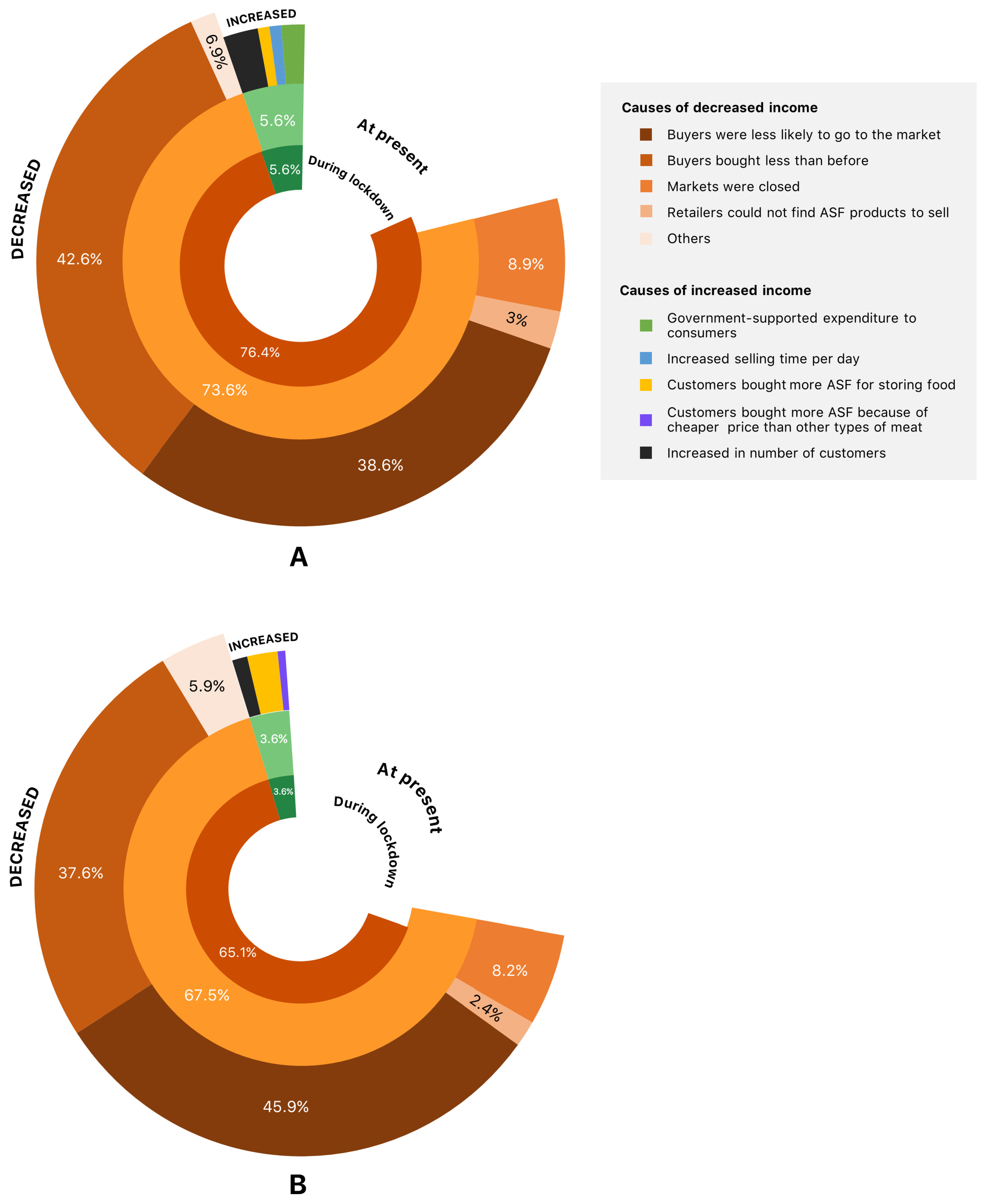

3.2.6. Impacts of COVID-19 to Retailer’s Income

3.3. Impacts of COVID-19 on Consumers

3.3.1. Impacts of COVID-19 on ASF Purchasing and Selection

3.3.2. Preference Type of Retails and Purchasing Frequency for Household Consumption

3.3.3. Average Amount of ASF Purchasing per Shopping Trip

3.3.4. Difficulties in Purchasing ASF at Different Periods

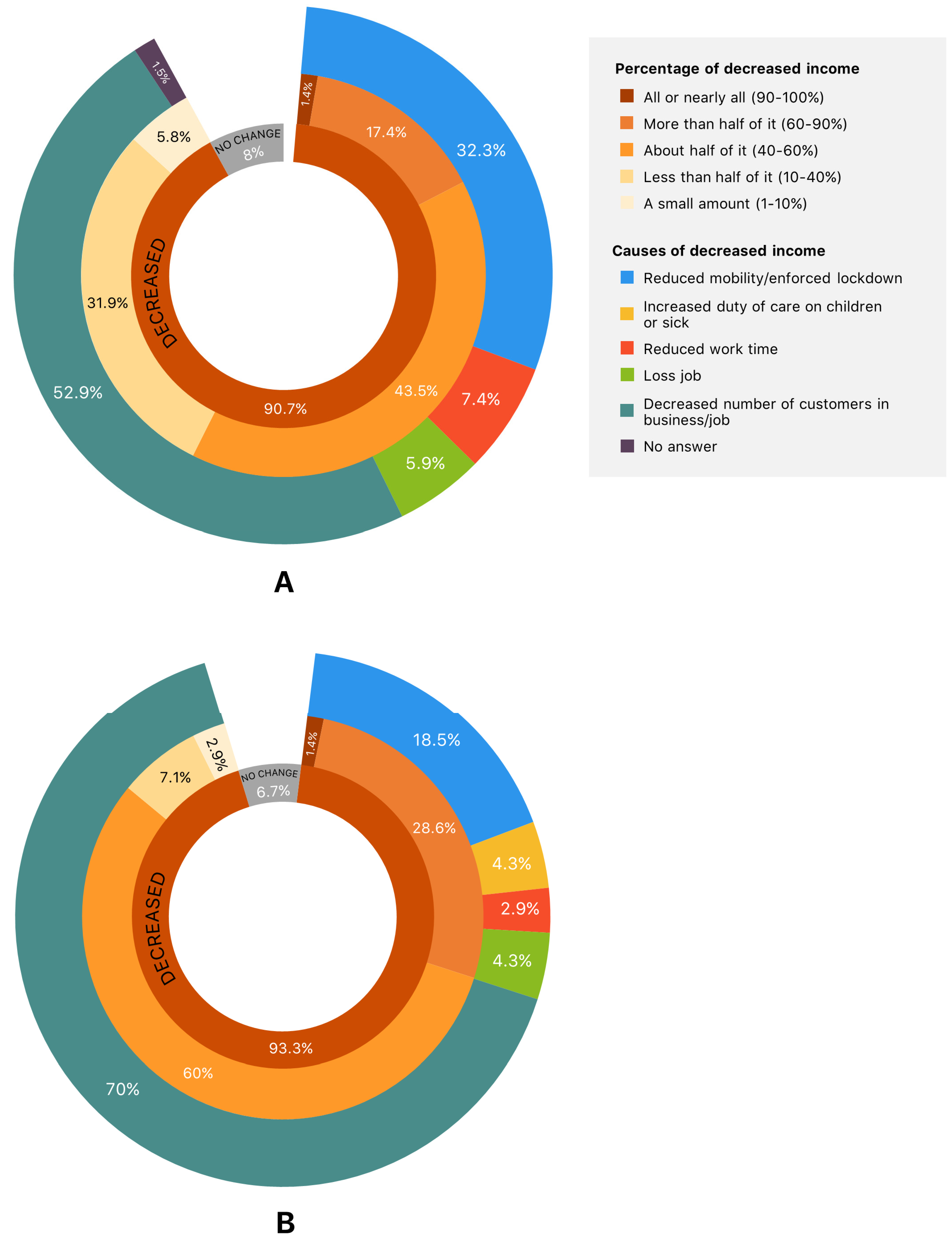

3.3.5. Impacts of COVID-19 to Consumer’s Incomes and Livelihood

3.4. KAP of Retailers toward COVID-19 and Food Safety

3.4.1. Knowledge of ASF Retailers toward COVID-19

3.4.2. Attitudes of Retailers toward COVID-19 Prevention and Food Safety Practices

3.4.3. Food Safety Practices of Retailers

3.4.4. Factors Related to KAP on COVID-19 and Food Safety of Retailers

3.5. KAP of Consumers toward COVID-19 and Food Safety

3.5.1. Knowledge of Consumers toward COVID-19

3.5.2. Attitudes of Consumers toward COVID-19 Prevention and Food Safety Practices

3.5.3. Food Safety Practices of Consumers

3.5.4. Factors Related to KAP on COVID-19 and Food Safety of Consumers

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts of COVID-19 and KAP of ASF Retailers

4.2. Impacts of COVID-19 and KAP of Consumers

4.3. Study Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kirtipal, N.; Bharadwaj, S.; Kang, S.G. From SARS to SARS-CoV-2, insights on structure, pathogenicity and immunity aspects of pandemic human coronaviruses. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2020, 85, 104502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Dhama, K.; Sharun, K.; Iqbal Yatoo, M.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.; Michalak, I.; Sah, R.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. COVID-19: Animals, veterinary and zoonotic links. Vet. Q. 2020, 40, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.R.; Cao, Q.D.; Hong, Z.S.; Tan, Y.Y.; Chen, S.D.; Jin, H.J.; Tan, K.S.; Wang, D.Y.; Yan, Y. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak—An update on the status. Mil. Med. Res. 2020, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; Kok, K.H.; Zhu, Z.; Chu, H.; To, K.K.; Yuan, S.; Yuen, K.Y. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Ahmad Farouk, I.; Lal, S.K. COVID-19: A Review on the Novel Coronavirus Disease Evolution, Transmission, Detection, Control and Prevention. Viruses 2021, 13, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. Coronavirus Beijing: Why an Outbreak Sparked a Salmon Panic in China. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-53089137 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Aday, S.; Aday, M.S. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual. Saf. 2020, 4, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M. COVID-19 Pandemic Transforms the Way We Shop, Eat and Think about Food, according to IFIC’s 2020 Food & Health Survey; Food Insight, International Food Information Council: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.Y. COVID-19 in South Korea. Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 96, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güner, R.; Hasanoğlu, I.; Aktaş, F. COVID-19: Prevention and control measures in community. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 50, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Critical Preparedness, Readiness and Response Actions for COVID-19: Interim Guidance, 22 March 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Adil, M.T.; Rahman, R.; Whitelaw, D.; Jain, V.; Al-Taan, O.; Rashid, F.; Munasinghe, A.; Jambulingam, P. SARS-CoV-2 and the pandemic of COVID-19. Postgrad. Med. J. 2021, 97, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frith, L. Lockdown, public good and equality during COVID-19. J. Med. Ethics. 2020, 46, 713–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, M.; Yar, M.K.; Badar, I.H.; Ali, S.; Islam, M.S.; Jaspal, M.H.; Hayat, Z.; Sardar, A.; Ullah, S.; Guevara-Ruiz, D. Meat Production and Supply Chain Under COVID-19 Scenario: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 660736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ./Rev. Can. D’agroeconomie 2020, 68, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deconinck, K.; Avery, E.; Jackson, L.A. Food Supply Chains and COVID-19: Impacts and Policy Lessons. EuroChoices 2020, 19, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirilak, S. Thailand’s Experience in the COVID-19 Response; Ministry of Public Health: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020.

- Fetansa, G.; Etana, B.; Tolossa, T.; Garuma, M.; Tesfaye Bekuma, T.; Wakuma, B.; Etafa, W.; Fekadu, G.; Mosisa, A. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of health professionals in Ethiopia toward COVID-19 prevention at early phase. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211012220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuben, R.C.; Danladi, M.M.A.; Saleh, D.A.; Ejembi, P.E. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices Towards COVID-19: An Epidemiological Survey in North-Central Nigeria. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatabu, A.; Mao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Kawashita, N.; Wen, Z.; Ueda, M.; Takagi, T.; Tian, Y.S. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices toward COVID-19 among university students in Japan and associated factors: An online cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, S.; Zhang, J.; Cao, M.; Chen, B. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of COVID-19 Among Urban and Rural Residents in China: A Cross-sectional Study. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prapaso, S.; Luvira, V.; Lawpoolsri, S.; Songthap, A.; Piyaphanee, W.; Chancharoenthana, W.; Muangnoicharoen, S.; Pitisuttithum, P.; Chanthavanich, P. Knowledge, attitude, and practices toward COVID-19 among the international travelers in Thailand. Trop. Dis. Travel Med. Vaccines 2021, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Hu, R.; Yin, L.; Yuan, X.; Tang, H.; Luo, L.; Chen, M.; Huang, D.; Wang, Y.; Yu, A.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of the Chinese public with respect to coronavirus disease (COVID-19): An online cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladiwala, Z.F.R.; Dhillon, R.A.; Zahid, I.; Irfan, O.; Khan, M.S.; Awan, S.; Khan, J.A. Knowledge, attitude and perception of Pakistanis towards COVID-19; a large cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hanawi, M.K.; Angawi, K.; Alshareef, N.; Qattan, A.M.N.; Helmy, H.Z.; Abudawood, Y.; Alqurashi, M.; Kattan, W.M.; Kadasah, N.A.; Chirwa, G.C.; et al. Knowledge, Attitude and Practice Toward COVID-19 Among the Public in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakdash, T.; Marsh, C. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs Regarding the COVID-19 Pandemic Among Women in Kansas. J. Community Health 2021, 46, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Mutukumira, A.N.; Shen, C. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and eating behavior in the advent of the global coronavirus pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.; Benson, T.; McCloat, A.; Mooney, E.; Elliott, C.; Dean, M.; Lavelle, F. Changes in Consumers’ Food Practices during the COVID-19 Lockdown, Implications for Diet Quality and the Food System: A Cross-Continental Comparison. Nutrients 2020, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Tian, X.; Ploeger, A. Exploring Chinese Consumers’ Online Purchase Intentions toward Certified Food Products during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods 2021, 10, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endriyas, M.; Kawza, A.; Alano, A.; Hussen, M.; Mekonnen, E.; Samuel, T.; Shiferaw, M.; Ayele, S.; Kelaye, T.; Misganaw, T.; et al. Knowledge and attitude towards COVID-19 and its prevention in selected ten towns of SNNP Region, Ethiopia: Cross-sectional survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho Alves, M.F.; Lima Mendonça, M.D.L.; Xavier Soares, J.J.; Leal, S.D.V.; Dos Santos, M.; Rodrigues, J.M.; Duarte Lopes, E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices towards COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in the resident cape-verdean population. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2021, 4, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, P.; Islam, M.S.; Duarte, P.M.; Tazerji, S.S.; Sobur, M.A.; El Zowalaty, M.E.; Ashour, H.M.; Rahman, M.T. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food production and animal health. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 121, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitro, A.; Sirikul, W.; Piankusol, C.; Rirermsoonthorn, P.; Seesen, M.; Wangsan, K.; Assavanopakun, P.; Surawattanasakul, V.; Kosai, A.; Sapbamrer, R. Acceptance, attitude, and factors affecting the intention to accept COVID-19 vaccine among Thai people and expatriates living in Thailand. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7554–7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anelich, L.; Lues, R.; Farber, J.M.; Parreira, V.R. SARS-CoV-2 and Risk to Food Safety. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 580551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knorr, D.; Khoo, C.H. COVID-19 and Food: Challenges and Research Needs. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 598913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srichan, P.; Apidechkul, T.; Tamornpark, R.; Yeemard, F.; Khunthason, S.; Kitchanapaiboon, S.; Wongnuch, P.; Wongphaet, A.; Upala, P. Knowledge, attitudes and preparedness to respond to COVID-19 among the border population of northern Thailand in the early period of the pandemic: A cross-sectional study. WHO South East Asia J. Public Health 2020, 9, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, S.C.; Boidya, P.; Haque, M.I.; Hossain, A.; Shams, Z.; Mamun, A.A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fish consumption and household food security in Dhaka city, Bangladesh. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 29, 100526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S. The impact of COVID-19 related ’stay-at-home’ restrictions on food prices in Europe: Findings from a preliminary analysis. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elleby, C.; Domínguez, I.P.; Adenauer, M.; Genovese, G. Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Global Agricultural Markets. Environ. Resour. Econ. (Dordr) 2020, 76, 1067–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. GDP growth (Annual %)—Thailand. Available online: https://cmu.to/dataworldbankorg (accessed on 10 June 2022).

- Niles, M.T.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.H.; Wentworth, T.; Biehl, E.; Neff, R. The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsahoryi, N.; Al-Sayyed, H.; Odeh, M.; McGrattan, A.; Hammad, F. Effect of COVID-19 on food security: A cross-sectional survey. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2020, 40, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kartari, A.; Özen, A.E.; Correia, A.; Wen, J.; Kozak, M. Impacts of COVID-19 on changing patterns of household food consumption: An intercultural study of three countries. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 26, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskaraca, G.; Bostanci, E.; Arslan, Y. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on eating and meat consumption habits of Turkish adults. Turk. J. Agric.-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 9, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, P.; Górna, I.; Miechowicz, I.; Przysławski, J. Changes in Eating Behaviour during SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic among the Inhabitants of Five European Countries. Foods 2021, 10, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attwood, S.; Hajat, C. How will the COVID-19 pandemic shape the future of meat consumption? Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 3116–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Five Keys to Safer Food Manual; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Item | No. of Retailers, n (%) | No. of Consumers, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban/Peri-Urban (n = 72) | Rural (n = 83) | Urban/Peri-Urban (n = 75) | Rural (n = 75) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 52 (72.2) | 57 (68.7) | 64 (85.3) | 60 (80.0) |

| Male | 20 (27.8) | 26 (31.3) | 11 (14.7) | 15 (20.0) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 46.8 ± 12.9 | 48.0 ± 14.6 | 44.9 ± 13.7 | 50.9 ± 12.7 |

| <20 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 0 |

| 20–29 | 7 (9.7) | 13 (15.7) | 12 (16.0) | 5 (6.7) |

| 30–39 | 17 (23.6) | 11 (13.3) | 12 (16.0) | 12 (16.0) |

| 40–49 | 17 (23.6) | 18 (21.7) | 24 (32.0) | 12 (16.0) |

| 50–60 | 19 (26.4) | 23 (27.7) | 14 (18.7) | 27 (36.0) |

| >60 | 12 (16.7) | 18 (21.7) | 12 (16.0) | 19 (25.3) |

| Education | ||||

| Illiterate | 3 (4.2) | 8 (9.6) | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.7) |

| Primary school | 29 (40.3) | 34 (41.0) | 17 (22.7) | 36 (48.0) |

| Secondary school | 3 (4.2) | 7 (8.4) | 12 (16.0) | 8 (10.7) |

| High school | 14 (19.4) | 17 (20.5) | 16 (21.3) | 12 (16.0) |

| College or higher | 23 (31.9) | 17 (20.5) | 29 (38.7) | 17 (22.7) |

| Type of ASF retailer | ||||

| Pork | 20 (27.8) | 36 (43.4) | NA | NA |

| Poultry | 17 (23.6) | 14 (16.9) | ||

| Beef | 4 (5.6) | 9 (10.8) | ||

| Fish/seafood | 31 (43.1) | 24 (28.9) | ||

| Business type | ||||

| Wholesale only | 1 (1.4) | 0 | NA | NA |

| Retail only | 53 (73.6) | 71 (85.5) | ||

| Wholesale and retail | 18 (25.0) | 12 (14.5) | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| Farmer | NA | NA | 0 | 2 (2.7) |

| Government officer/staff | NA | NA | 2 (2.7) | 2 (2.7) |

| Worker | NA | NA | 1 (1.3) | 7 (9.3) |

| Private business | 72 (100) | 83 (100) | 67 (89.3) | 59 (78.7) |

| Housewife | NA | NA | 3 (4.0) | 4 (5.3) |

| Students | NA | NA | 2 (2.7) | 1 (1.3) |

| Household monthly income | ||||

| ≤200 USD | NA | NA | 3 (4.0) | 8 (10.7) |

| 201–400 USD | 21 (28.0) | 18 (24.0) | ||

| 401–600 USD | 12 (16.0) | 18 (24.0) | ||

| 601–800 USD | 16 (21.3) | 13 (17.3) | ||

| 801–1000 USD | 8 (10.7) | 9 (12.0) | ||

| 1001–2000 USD | 6 (8.0) | 5 (6.7) | ||

| >2000 USD | 7 (9.3) | 1 (1.3) | ||

| NA * | 2 (2.7) | 3 (4.0) | ||

| Number of family members | ||||

| <3 | NA | NA | 29 (38.7) | 23 (30.7) |

| 3–5 | 38 (50.7) | 43 (57.3) | ||

| >5 | 8 (10.7) | 9 (12.0) | ||

| Variable | n | Knowledge toward COVID-19 | Attitudes toward COVID-19 Prevention | Attitudes toward Food Safety Practices | Practices toward Food Safety (During Partial Lockdown) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good n (%) | ORcrude (95%CI) | Good n (%) | ORcrude (95%CI) | Good n (%) | ORcrude (95%CI) | Good n (%) | ORcrude (95%CI) | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 46 | 28 (60.9) | 1 | 35 (76.1) | 1 | 25 (54.3) | 1 | 22 (47.8) | 1 |

| Female | 109 | 88 (81.6) | 2.69 b (1.26, 5.76) | 69 (73.1) | 0.54 (0.25, 1.18) | 66 (60.6) | 1.29 (0.64, 2.59) | 64 (58.7) | 1.55 (0.78, 3.10) |

| Age group | |||||||||

| 20–29 | 20 | 18 (90.0) | 1 | 13 (65.0) | 1 | 10 (50.0) | 1 | 8 (40.0) | 1 |

| 30–39 | 28 | 20 (71.4) | 0.28 (0.05, 1.48) | 19 (67.9) | 1.14 (0.34, 3.83) | 15 (53.6) | 1.15 (0.37, 3.64) | 20 (71.4) | 3.75 (1.11, 12.62) |

| 40–49 | 35 | 27 (77.1) | 0.38 (0.07, 1.97) | 23 (65.7) | 1.03 (0.33, 3.27) | 21 (60.0) | 1.50 (0.50, 4.54) | 17 (48.6) | 1.42 (0.47, 4.31) |

| 50–60 | 42 | 31 (73.8) | 0.31 (0.06, 1.57) | 27 (64.3) | 0.97 (0.32, 2.95) | 25 (59.5) | 1.47 (0.50, 4.29) | 27 (64.3) | 2.70 (0.90, 8.07) |

| >60 | 30 | 20 (66.7) | 0.22 (0.04, 1.15) | 22 (73.3) | 1.48 (0.44, 5.04) | 20 (66.7) | 2.00 (0.63, 6.38) | 14 (46.7) | 1.31 (0.42, 4.13) |

| Education | |||||||||

| Illiterate | 11 | 7 (63.6) | 1 | 6 (54.5) | 1 | 6 (54.5) | 1 | 4 (36.4) | 1 |

| Primary school | 63 | 41 (65.1) | 1.06 (0.28, 4.04) | 43 (68.3) | 1.79 (0.49, 6.57) | 38 (60.3) | 1.27 (0.35, 4.60) | 38 (60.3) | 2.66 (0.70, 10.04) |

| Secondary school | 10 | 8 (80.0) | 2.29 (0.32, 16.51) | 8 (80.0) | 3.33 (0.47, 23.47) | 6 (60.0) | 1.25 (0.22, 7.08) | 6 (60.0) | 2.63 (0.45, 15.31) |

| High school | 31 | 25 (80.6) | 2.38 (0.52, 10.86) | 21 (67.7) | 1.75 (0.43, 7.14) | 17 (54.8) | 1.01 (0.25, 4.03) | 20 (64.5) | 3.18 (0.76, 13.32) |

| College or higher | 40 | 35 (87.5) | 4.00 (0.85, 18.75) | 26 (65.0) | 1.55 (0.40, 5.99) | 24 (60.0) | 1.25 (0.33, 4.80) | 18 (45.0) | 1.43 (0.36, 5.68) |

| Type of ASF | |||||||||

| Pork | 56 | 38 (67.9) | 1 | 41 (73.2) | 1 | 35 (62.5) | 1 | 40 (71.4) | 1 |

| Poultry | 31 | 23 (74.2) | 1.36 (0.51, 3.63) | 19 (61.3) | 0.58 (0.23, 1.47) | 17 (54.8) | 0.73 (0.30, 1.78) | 16 (51.6) | 0.43 (0.17, 1.06) |

| Beef | 13 | 11 (84.6) | 2.61 (0.52, 13.00) | 9 (69.2) | 0.82 (0.22, 3.08) | 6 (46.2) | 0.51 (0.15, 1.74) | 7 (53.8) | 0.47 (0.14, 1.61) |

| Fish/seafood | 55 | 44 (80.0) | 1.89 (0.80, 4.51) | 35 (63.6) | 0.64 (0.29, 1.44) | 33 (60.0) | 0.90 (0.42, 1.93) | 23 (41.8) | 0.29 (0.13, 0.63) |

| Business type a | |||||||||

| Retail only | 124 | 89 (71.8) | 1 | 86 (69.4) | 1 | 81 (65.3) | 1 | 71 (57.3) | 1 |

| Wholesale and retail | 30 | 26 (86.7) | 2.56 (0.83, 7.86) | 18 (60.0) | 0.66 (0.29, 1.51) | 9 (30.0) | 0.23 (0.10, 0.54) | 15 (50.0) | 0.75 (0.34, 1.66) |

| COVID-19 knowledge | |||||||||

| Poor knowledge | 39 | 0 (0) | - | 23 (59.0) | 1 | 24 (61.5) | 1 | 26 (66.7) | 1 |

| Good knowledge | 116 | 116 (100) | - | 81 (69.8) | 1.61 (0.76, 3.41) | 67 (57.8) | 0.85 (0.41, 1.80) | 60 (51.7) | 0.54 (0.25, 1.14) |

| Food safety attitudes | |||||||||

| Poor attitude | 64 | 49 (76.6) | 1 | 28 (43.8) | 1 | 0 (0) | - | 35 (54.7) | 1 |

| Positive attitude | 91 | 67 (73.6) | 0.85 (0.41, 1.80) | 76 (83.5) | 6.51 (3.10, 13.68) | 91 (100) | - | 51 (56.0) | 1.06 (0.56, 2.01) |

| Variable | n | Knowledge toward COVID-19 | Attitudes toward COVID-19 Prevention | Attitudes toward Food Safety Practices | Practices toward Food Safety (During Partial Lockdown) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good n (%) | ORcrude (95%CI) | Good n (%) | ORcrude (95%CI) | Good n (%) | ORcrude (95%CI) | Good n (%) | ORcrude (95%CI) | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 26 | 17 (65.4) | 1 | 9 (34.6) | 1 | 12 (46.2) | 1 | 16 (61.5) | 1 |

| Female | 124 | 88 (71.0) | 1.29 (0.53, 3.17) | 67 (54.0) | 2.22 (0.92, 5.36) | 73 (58.9) | 1.67 (0.71, 3.91) | 81 (65.3) | 1.18 (0.49, 2.82) |

| Age group a | |||||||||

| 20–29 | 17 | 13 (76.5) | 1 | 8 (47.1) | 1 | 4 (23.5) | 1 | 11 (64.7) | 1 |

| 30–39 | 24 | 18 (75.0) | 0.92 (0.22, 3.94) | 13 (54.2) | 1.33 (0.38, 4.62) | 15 (62.5) | 5.42 d (1.35, 21.80) | 17 (70.8) | 1.32 (0.35, 5.00) |

| 40–49 | 36 | 31 (86.1) | 1.91 (0.44, 8.26) | 17 (47.2) | 1.01 (0.32, 3.20) | 20 (55.6) | 4.06 (1.11, 14.90) | 22 (61.1) | 0.86 (0.26, 2.84) |

| 50–60 | 41 | 24 (58.5) | 0.43 (0.12, 1.56) | 23 (56.1) | 1.44 (0.46, 4.47) | 28 (68.3) | 7.00 (1.91, 25.67) | 27 (65.9) | 1.05 (0.32, 3.44) |

| >60 | 31 | 18 (58.1) | 0.43 (0.11, 1.61) | 15 (48.4) | 1.05 (0.32, 3.45) | 18 (58.1) | 4.50 (1.19, 16.99) | 20 (64.5) | 0.99 (0.29, 3.42) |

| Education b | |||||||||

| Primary school | 53 | 28 (52.8) | 1 | 31 (58.5) | 1 | 32 (60.4) | 1 | 39 (73.6) | 1 |

| Secondary school | 20 | 16 (80.0) | 3.57 (1.05, 12.11) | 9 (45.0) | 0.58 (0.21, 1.64) | 10 (50.0) | 0.66 (0.23, 1.85) | 9 (45.0) | 0.29 (0.10, 0.86) |

| High school | 28 | 21 (75.0) | 2.68 (0.97, 7.36) | 14 (50.0) | 0.71 (0.28, 1.78) | 17 (60.7) | 1.01 (0.40, 2.59) | 17 (60.7) | 0.55 (0.21, 1.47) |

| College or higher | 46 | 38 (82.6) | 4.24 (1.67, 10.79) | 20 (43.5) | 0.55 (0.25, 1.21) | 24 (52.2) | 0.72 (0.32, 1.59) | 30 (65.2) | 0.67 (0.28, 1.59) |

| Occupation | |||||||||

| Private business | 126 | 87 (69.0) | 1 | 72 (57.1) | 1 | 78 (61.9) | 1 | 88 (69.8) | 1 |

| Others | 24 | 18 (75.0) | 1.34 (0.50, 3.65) | 4 (16.7) | 0.15 (0.05, 0.46) | 7 (29.2) | 0.25 (0.10, 0.66) | 9 (37.5) | 0.26 (0.10, 0.64) |

| Household monthlyincome (USD) c | |||||||||

| ≤200 | 11 | 7 (63.6) | 1 | 5 (45.5) | 1 | 5 (45.5) | 1 | 7 (63.6) | 1 |

| 201–400 | 39 | 25 (64.1) | 1.02 (0.25, 4.10) | 16 (41.0) | 0.83 (0.22, 3.21) | 19 (48.7) | 1.14 (0.30, 4.37) | 25 (64.1) | 1.02 (0.25, 4.10) |

| 401–600 | 30 | 21 (70.0) | 1.33 (0.31, 5.72) | 15 (50.0) | 1.20 (0.30, 4.80) | 19 (63.3) | 2.07 (0.51, 8.41) | 17 (56.7) | 0.75 (0.18, 3.11) |

| 601–800 | 29 | 23 (79.3) | 2.19 (0.48, 10.04) | 17 (58.6) | 1.70 (0.42, 6.88) | 22 (75.9) | 3.77 (0.88, 16.24) | 19 (65.5) | 1.09 (0.26, 4.62) |

| 801–1000 | 17 | 12 (70.6) | 1.37 (0.27, 6.87) | 12 (70.6) | 2.88 (0.59, 13.98) | 9 (52.9) | 1.35 (0.29, 6.18) | 13 (76.5) | 1.86 (0.35, 9.79) |

| 1001–2000 | 11 | 8 (72.7) | 1.52 (0.25, 9.29) | 4 (36.4) | 0.69 (0.12, 3.78) | 4 (36.4) | 0.69 (0.12, 3.78) | 7 (63.6) | 1.00 (0.18, 5.68) |

| >2000 | 8 | 6 (75.0) | 1.71 (0.23, 12.89) | 5 (62.5) | 2.00 (0.31, 12.84) | 6 (75.0) | 3.60 (0.49, 26.40) | 7 (87.5) | 4.00 (0.35, 45.38) |

| Number of family members | |||||||||

| <3 | 52 | 42 (80.8) | 1 | 32 (61.5) | 1 | 33 (63.5) | 1 | 34 (65.4) | 1 |

| 3–5 | 81 | 56 (69.1) | 0.53 (0.23, 1.23) | 41 (50.6) | 0.64 (0.32, 1.30) | 45 (55.6) | 0.72 (0.35, 1.47) | 50 (61.7) | 0.85 (0.41, 1.76) |

| >5 | 17 | 7 (41.2) | 0.17 (0.05, 0.55) | 3 (17.6) | 0.13 (0.03, 0.53) | 7 (41.2) | 0.40 (0.13, 1.23) | 13 (76.5) | 1.72 (0.49, 6.05) |

| COVID-19 knowledge | |||||||||

| Poor knowledge | 45 | 0 (0) | - | 19 (42.2) | 1 | 24 (53.3) | 1 | 35 (77.8) | 1 |

| Good knowledge | 105 | 105 (100) | - | 57 (54.3) | 1.63 (0.80, 3.29) | 61 (58.1) | 1.21 (0.60, 2.45) | 62 (59.0) | 0.41 (0.18, 0.92) |

| Food safety attitudes | |||||||||

| Poor attitude | 65 | 44 (67.7) | 1 | 23 (35.4) | 1 | 0 | - | 37 (56.9) | 1 |

| Positive attitude | 85 | 61 (71.8) | 1.21 (0.60, 2.45) | 53 (62.4) | 3.02 (1.55, 5.92) | 85 (100) | - | 60 (70.6) | 1.82 (0.92, 3.58) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jainonthee, C.; Dang-Xuan, S.; Nguyen-Viet, H.; Unger, F.; Chaisowwong, W. Impacts of the Pandemic, Animal Source Food Retailers’ and Consumers’ Knowledge and Attitudes toward COVID-19, and Their Food Safety Practices in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610187

Jainonthee C, Dang-Xuan S, Nguyen-Viet H, Unger F, Chaisowwong W. Impacts of the Pandemic, Animal Source Food Retailers’ and Consumers’ Knowledge and Attitudes toward COVID-19, and Their Food Safety Practices in Chiang Mai, Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610187

Chicago/Turabian StyleJainonthee, Chalita, Sinh Dang-Xuan, Hung Nguyen-Viet, Fred Unger, and Warangkhana Chaisowwong. 2022. "Impacts of the Pandemic, Animal Source Food Retailers’ and Consumers’ Knowledge and Attitudes toward COVID-19, and Their Food Safety Practices in Chiang Mai, Thailand" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610187

APA StyleJainonthee, C., Dang-Xuan, S., Nguyen-Viet, H., Unger, F., & Chaisowwong, W. (2022). Impacts of the Pandemic, Animal Source Food Retailers’ and Consumers’ Knowledge and Attitudes toward COVID-19, and Their Food Safety Practices in Chiang Mai, Thailand. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10187. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610187