Retrospective Evaluation of Discharge Planning Linked to a Long-Term Care 2.0 Project in a Medical Center

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Participants

2.2. Multi-Dimensional Assessment Instrument (MDAI) and Long-Term Care Case-Mix System (LTC-CMS)

- Individual communication skills or short-term memory assessment.

- Activity of Daily Living (ADLs) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs).

- Special complex care needs.

- Home environment and social participation.

- Emotional and behavioral patterns.

- Primary caregiver load, work, and support.

2.3. Measurement

2.3.1. Dependent Variables

2.3.2. Independent Variables

2.3.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

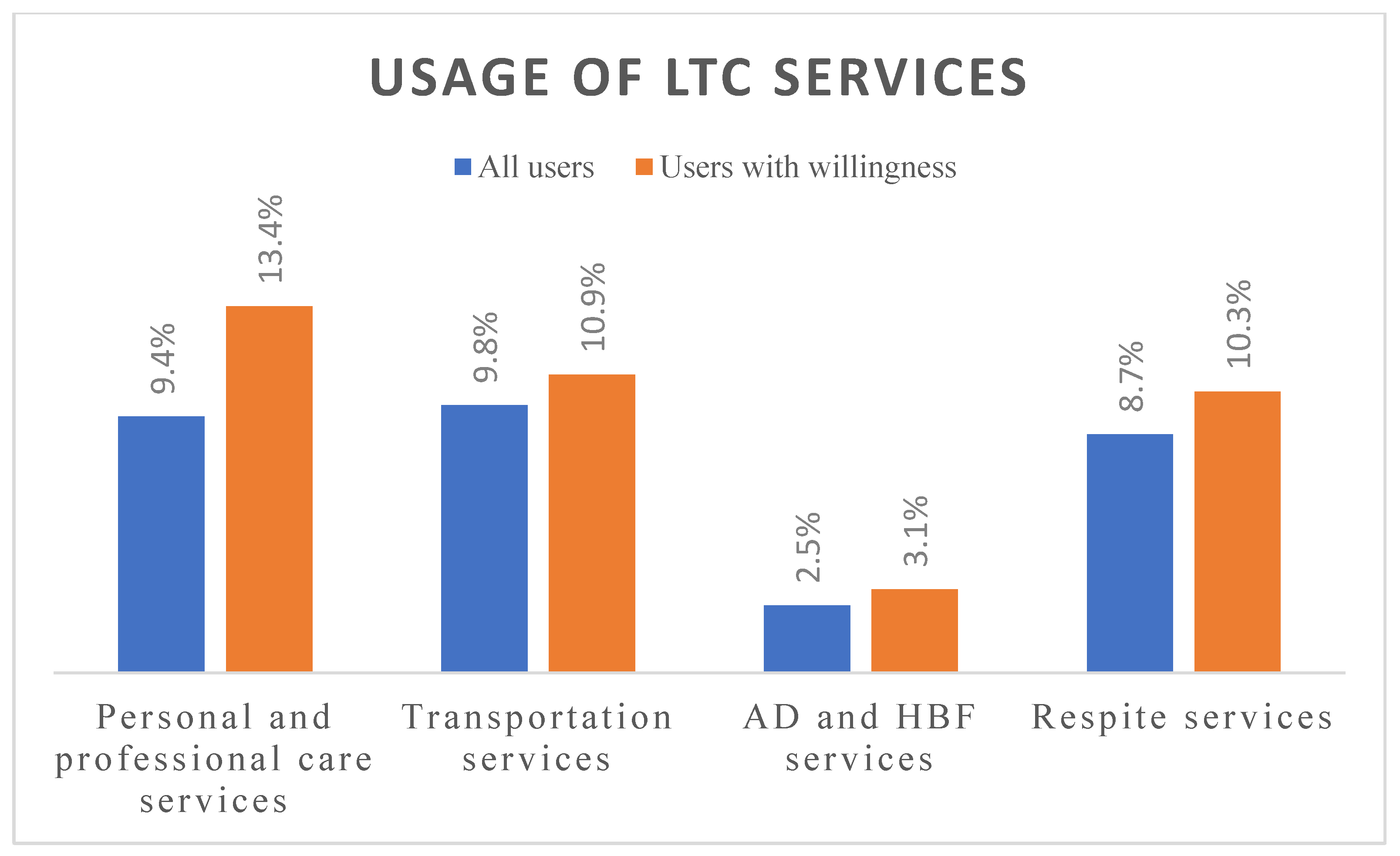

3.2. Users by LTC Services

3.3. Backward Stepwise Regression Model for Factors in Referrals to LTC Services

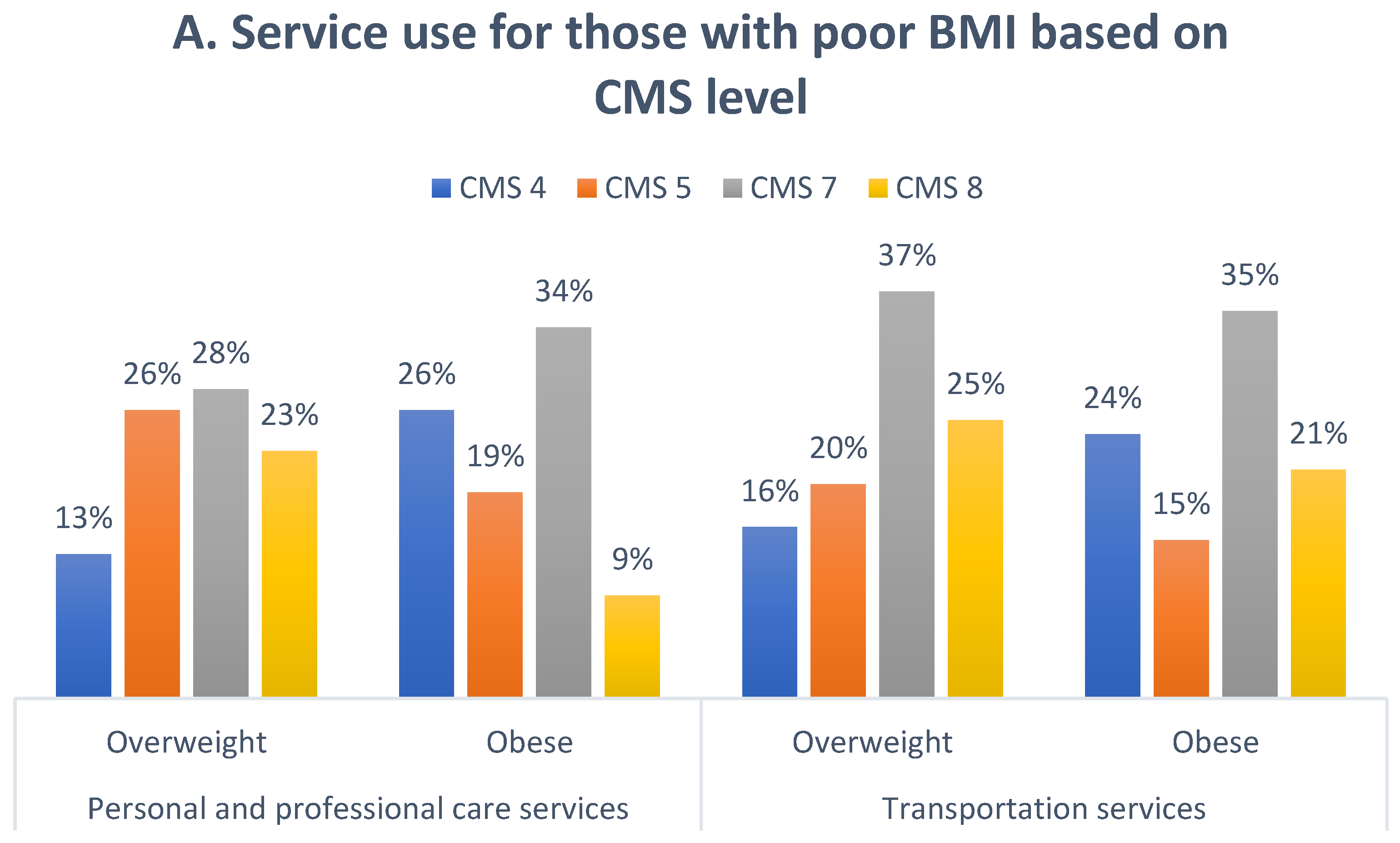

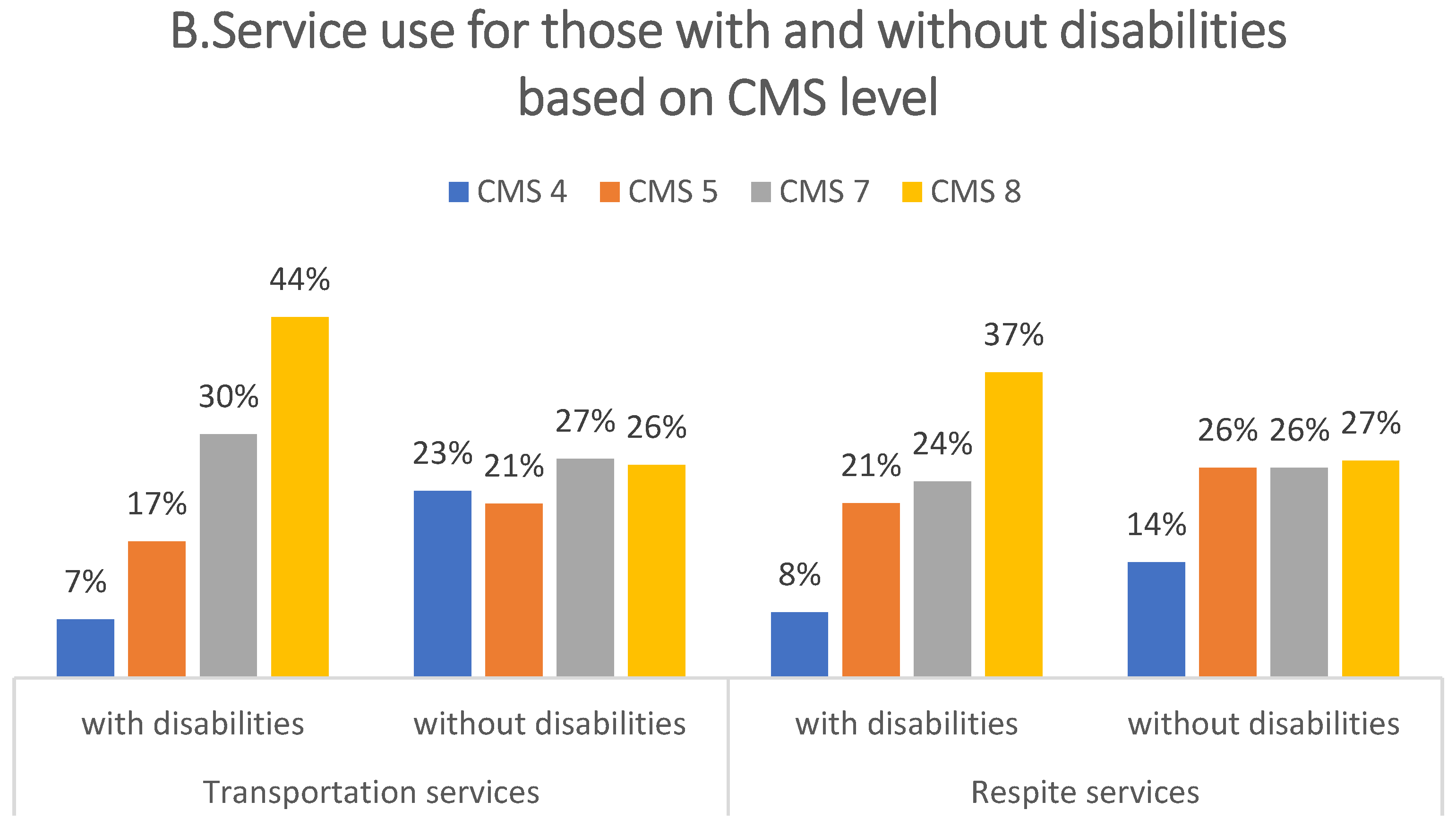

3.4. CMS-Related Factors That Affect Service Use

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- The World Bank. Population Ages 65 and Above (% of Total Population). 2019. Available online: https://data.Worldbank.Org/indicator/sp.Pop.65up.To.Zs (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- George, L. Ministry of the Interior: Taiwan Officially Becomes an Aged Society with People over 65 Years Old Breaking the 14% Mark (2018/04/10). Taiwan News. 2018. Available online: https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3402395 (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Statistics of the Ministry of Health and Welfare. Long-Term Care Service Network Plan (Phase I 2013 to 2016 Year Approved Book). 2017. Available online: http://www.ey.gov.tw/Upload/RelFile/27/704779/de38a0eb-6a1a-46b4-acaf-d5ad76eb0235.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Li, C.L.; Lin, L.P.; Hsu, S.W.; Lin, J.D. Exploratory review of needs and use difficulties for long-term care services in elderly people. Taiwan J. Elder. Care 2016, 12, 48–57. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Fu, T.H. Policies and transformation of long-term care system in taiwan. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2020, 24, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, M.-J. Long-term care system in taiwan: The 2017 major reform and its challenges. Ageing Soc. 2020, 40, 1334–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, P.Y.; Ku, L.J.E.; Pai, M.C.; Liu, L.F. Long-term care services use and reasons for non-use by elders with dementia and their families. Taiwan J. Public Health 2017, 36, 375–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. The Ten-Year Long Term Care Plan 2.0 Prospectus; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Taipei, Taiwan, 2016. Available online: https://ltc.mmc.edu.tw/ImgMmcEdu/20160803083657.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Yang, C.C.; Hsueh, J.Y.; Wei, C.Y. Current status of long-term care in taiwan: Transition of long-term care plan from 1.0 to 2.0. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020, 9, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Lannin, N.A.; Clemson, L.M.; Cameron, I.D.; Shepperd, S. Discharge planning from hospital. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016, Cd000313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.O.; Luk, J.K.; Chan, T.C.; Mok, W.W.; Chan, F.H. Effectiveness of a discharge planning and community support programme in preventing readmission of high-risk older patients. Hong Kong Med. J. 2015, 21, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodakowski, J.; Rocco, P.B.; Ortiz, M.; Folb, B.; Schulz, R.; Morton, S.C.; Leathers, S.C.; Hu, L.; James, A.E., 3rd. Caregiver integration during discharge planning for older adults to reduce resource use: A metaanalysis. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrabad, R.R. Introducing a new nursing care model for patients with chronic conditions. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 3794–3796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Coleman, E.A.; Boult, C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2003, 51, 556–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, E.H.; Young, D.L.; Friedman, L.A.; Brotman, D.J.; Klein, L.M.; Friedman, M.; Needham, D.M. Routine inpatient mobility assessment and hospital discharge planning. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-C.; Chang, W.-T.; Huang, C.-Y.; Tseng, P.-L.; Lee, C.-H. Factors influencing patients using long-term care service of discharge planning by andersen behavioral model: A hospital-based cross-sectional study in eastern taiwan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Welfare. Long-Term Care Case-Mix Assessment Scale (v2); Ministry of Health and Welfare: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018; pp. 1–28. Available online: https://1966.gov.tw/LTC/cp-4015-42461-201.html (accessed on 10 December 2021). (In Chinese)

- Hsu, H.C.; Chen, C.F. Ltc 2.0: The 2017 reform of home- and community-based long-term care in taiwan. Health Policy 2019, 123, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Promotion Administration and Ministry of Health and Welfare. Taiwan’s Obesity Prevention and Management Strategy, 1st ed.; Ministry of Health and Welfare: Taipei, Taiwan, 2018. Available online: https://www.hpa.gov.tw/File/Attach/10299/File_11744.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Chowdhury, M.Z.I.; Turin, T.C. Variable selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction modelling. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legislative Council Secretariat. Community Care Services for the Elderly in Germany and Japan (in 12/20-21); Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: Hong Kong, China, 2021; Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legislative_Council_of_Hong_Kong (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Yin, M.-F.; Ting, S.-T.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Chan, H.-Y.; Pan, S.-L.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, S.-J.; Liu, H.-Y. The project to improve the transfer rate of long-term care 2.0. Formos. J. Med. 2022, 26, 210–218. [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, F.; Stearns, S.C.; Norton, E.C.; Spector, W. Proximity to death and participation in the long-term care market. Health Econ. 2009, 18, 867–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ku, L.J.; Liu, L.F.; Wen, M.J. Trends and determinants of informal and formal caregiving in the community for disabled elderly people in taiwan. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2013, 56, 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.H.; Tsay, S.F. Elderly and long-term care trends and policy in taiwan: Challenges and opportunities for health care professionals. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2012, 28, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.Y.; Hu, H.Y.; Huang, N.; Fang, Y.T.; Chou, Y.J.; Li, C.P. Determinants of long-term care services among the elderly: A population-based study in taiwan. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.J.; Chou, K.-L. Long-term care service needs and planning for the future: A study of middle-aged and older adults in hong kong. Ageing Soc. 2017, 39, 221–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics; Center for Disease Control, and Preventio. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-Term Trends in Health; National Center for Health Statistics (US): Hyattsville, MD, USA, 2017.

- Liu, C.; Eom, K.; Matchar, D.B.; Chong, W.F.; Chan, A.W. Community-based long-term care services: If we build it, will they come? J. Aging Health 2016, 28, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, S.; Jebb, S.A.; Gray, A.; Green, J.; Reeves, G.; Beral, V.; Mihaylova, B.; Cairns, B.J. Body mass index and use and costs of primary care services among women aged 55–79 years in england: A cohort and linked data study. Int. J. Obes. 2019, 43, 1839–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc Hugh, S.; O’Neill, C.; Browne, J.; Kearney, P.M. Body mass index and health service utilisation in the older population: Results from the irish longitudinal study on ageing. Age Ageing 2014, 44, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novosel, L.M.; Grant, C.A.; Dormin, L.M.; Coleman, T.M. Obesity and disability in older adults. Nurse Pract. 2017, 42, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Frequency | Percent | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤69 | 433 | 20.1 |

| 70–79 | 701 | 32.5 | |

| ≥80 | 1021 | 47.4 | |

| Gender | Female | 1109 | 51.5 |

| Male | 1046 | 48.5 | |

| Education | none | 605 | 28.1 |

| primary school | 1004 | 46.6 | |

| junior high and above | 490 | 22.7 | |

| Marital status | unmarried | 617 | 28.6 |

| married | 1538 | 71.4 | |

| Income | low income | 143 | 6.6 |

| general income | 2007 | 93.1 | |

| Living area | urban | 862 | 40.0 |

| rural | 1291 | 59.9 | |

| Disability card holder | yes | 656 | 30.4 |

| no | 1499 | 69.6 | |

| Dementia | without | 2017 | 93.6 |

| with | 138 | 6.4 | |

| Body Mass Index | underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 255 | 11.8 |

| normal (18.5 ≤ BMI < 24) | 938 | 43.5 | |

| overweight(24 ≤ BMI < 27) | 473 | 21.9 | |

| obesity(BMI ≥ 27) | 467 | 21.7 | |

| Primary caregiver | foreign caregiver | 170 | 7.9 |

| daughter | 482 | 22.4 | |

| son | 892 | 41.4 | |

| spouse | 508 | 23.6 | |

| other relatives | 87 | 4.0 | |

| none | 16 | 0.7 | |

| CMS level | level 2 | 43 | 2.0 |

| level 3 | 65 | 3.0 | |

| level 4 | 415 | 19.3 | |

| level 5 | 428 | 19.9 | |

| level 6 | 65 | 3.0 | |

| level 7 | 504 | 23.4 | |

| level 8 | 635 | 29.5 |

| A. Care and Professional Services | B. Transportation Services | C. Respite Services | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Female | 1.39 | (1.02–1.90) | 0.036 | ||||||

| Married | 1.37 | (0.96–1.96) | 0.087 | ||||||

| With disabilities | 1.47 | (1.09–1.99) | 0.012 | 1.57 | (1.15–2.14) | 0.005 | |||

| CMS level (2–8) | 1.16 | (1.06–1.27) | 0.001 | ||||||

| Primary education | 1.09 | (0.77–1.56) | 0.620 | ||||||

| Higher education | 1.51 | (1.02–2.25) | 0.041 | ||||||

| BMI < 18.5 (underweight) | 0.87 | (0.51–1.48) | 0.608 | 0.69 | (0.40–1.19) | 0.183 | |||

| 24 ≤ BMI < 27 (overweight) | 1.42 | (0.98–2.07) | 0.063 | 1.40 | (0.96–2.03) | 0.079 | |||

| BMI ≥ 27 (obesity) | 1.46 | (1.01–2.12) | 0.045 | 1.81 | (1.27–2.59) | 0.001 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, S.-T.; Chen, C.-M.; Su, Y.-Y.; Chang, S.-C. Retrospective Evaluation of Discharge Planning Linked to a Long-Term Care 2.0 Project in a Medical Center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610139

Huang S-T, Chen C-M, Su Y-Y, Chang S-C. Retrospective Evaluation of Discharge Planning Linked to a Long-Term Care 2.0 Project in a Medical Center. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610139

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Su-Tsai, Chun-Min Chen, Yu-Yung Su, and Shu-Chen Chang. 2022. "Retrospective Evaluation of Discharge Planning Linked to a Long-Term Care 2.0 Project in a Medical Center" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610139

APA StyleHuang, S.-T., Chen, C.-M., Su, Y.-Y., & Chang, S.-C. (2022). Retrospective Evaluation of Discharge Planning Linked to a Long-Term Care 2.0 Project in a Medical Center. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610139