Medical Students’ Perspectives on LGBTQI+ Healthcare and Education in Germany: Results of a Nationwide Online Survey

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Participants

2.2. Recruitment

2.3. The Survey

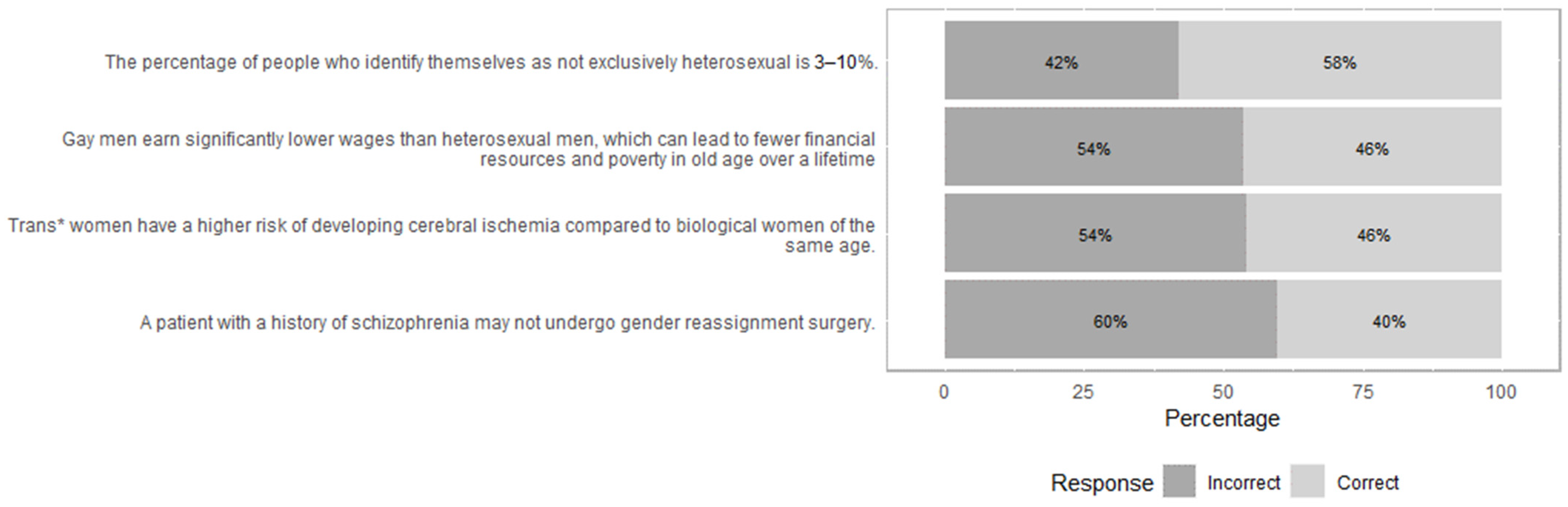

2.3.1. Knowledge

2.3.2. Prejudice

2.3.3. Contact

2.3.4. Comfort

2.3.5. Efficacy Beliefs

2.3.6. Experienced Teaching

2.3.7. Importance of Teaching

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participants

3.2. Knowledge

3.3. Prejudice

3.4. Contact

3.5. Comfort

3.6. Efficacy Beliefs

3.7. Experienced Teaching

3.8. Teaching Importance

3.9. Subgroup Comparisons

3.10. Predictive Analyses

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Female, Mem (n = 196) | Female, NonMem (n = 305) | Male, Mem (n = 69) | Male, NonMem (n = 89) | Diverse, Mem (n = 11) | 2-Way ANOVA (“Diverse” Not Included) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | SoV | F | df | df Error | p | η 2 | |

| Knowledge | 15.84 | 15.12 | 15.62 | 14.56 | 15.82 | Gender | 4.981 | 1 | 655 | 0.026 | 0.01 |

| (1.55) | (1.88) | (1.76) | (2.44) | (1.60) | Community | 29.222 | 1 | 655 | <0.001 | 0.04 | |

| Interaction | 0.998 | 1 | 655 | 0.318 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Prejudice | 0.21 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.99 | 0.09 | Gender | 15.51 | 1 | 655 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| (0.69) | (0.83) | (0.51) | (1.73) | (0.30) | Community | 15.76 | 1 | 655 | <0.001 | 0.02 | |

| Interaction | 15.40 | 1 | 655 | <0.001 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Contact | 2.60 | 1.87 | 2.68 | 1.49 | 2.91 | Gender | 2.757 | 1 | 655 | 0.097 | 0.00 |

| (0.93) | (0.97) | (0.85) | (1.06) | (0.83) | Community | 122.436 | 1 | 655 | <0.001 | 0.16 | |

| Interaction | 6.678 | 1 | 655 | 0.010 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Comfort | 51.88 | 49.45 | 51.54 | 49.03 | 52.73 | Gender | 0.294 | 1 | 655 | 0.588 | 0.00 |

| (4.85) | (5.99) | (5.26) | (6.48) | (3.93) | Community | 29.347 | 1 | 655 | <0.001 | 0.04 | |

| Interaction | 0.006 | 1 | 655 | 0.940 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Efficacy Beliefs | 5.77 | 5.71 | 5.70 | 6.91 | 5.36 | Gender | 13.159 | 1 | 655 | <0.001 | 0.02 |

| (1.97) | (1.84) | (2.03) | (2.17) | (2.67) | Community | 2.684 | 1 | 655 | 0.102 | 0.00 | |

| Interaction | 12.509 | 1 | 655 | <0.001 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Exp. Teaching | 1.58 | 1.61 | 1.59 | 1.72 | 1.80 | Gender | 1.242 | 1 | 639 | 0.265 | 0.00 |

| (0.59) | (0.61) | (0.60) | (0.70) | (0.43) | Community | 0.994 | 1 | 639 | 0.319 | 0.00 | |

| Interaction | 0.844 | 1 | 639 | 0.358 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Imp. of Teaching | 7.57 | 7.10 | 7.58 | 5.27 | 7.82 | Gender | 56.26 | 1 | 645 | <0.001 | 0.08 |

| (0.99) | (1.45) | (0.86) | (2.38) | (0.60) | Community | 63.04 | 1 | 645 | <0.001 | 0.09 | |

| Interaction | 46.79 | 1 | 645 | <0.001 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Knowledge | Prejudice | Contact | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groups | Diff | 95% Conf Int | p | Diff | 95% Conf Int | p | Diff | 95% Conf Int | p | |

| M:0 | F:0 | −0.563 | −1.142, 0.016 | 0.06 | 0.645 | 0.351, 0.938 | <0.001 | −0.378 | −0.675, −0.081 | 0.006 |

| F:1 | F:0 | 0.717 | 0.277, 1.157 | <0.001 | −0.13 | −0.353, 0.093 | 0.436 | 0.73 | 0.504, 0.956 | <0.001 |

| M:1 | F:0 | 0.499 | −0.142, 1.139 | 0.187 | −0.17 | −0.495, 0.154 | 0.53 | 0.809 | 0.48, 1.138 | <0.001 |

| F:1 | M:0 | 1.28 | 0.666, 1.894 | <0.001 | −0.774 | −1.086, −0.463 | <0.001 | 1.108 | 0.793, 1.423 | <0.001 |

| M:1 | M:0 | 1.061 | 0.291, 1.832 | 0.002 | −0.815 | −1.205, −0.424 | <0.001 | 1.187 | 0.791, 1.582 | <0.001 |

| M:1 | F:1 | −0.219 | −0.891, 0.454 | 0.837 | −0.04 | −0.381, 0.3 | 0.99 | 0.079 | −0.266, 0.424 | 0.935 |

| Comfort | Efficacy Beliefs | Imp. of Teaching | ||||||||

| Groups | Diff | 95% Conf Int | p | Diff | 95% Conf Int | p | Diff | 95% Conf Int | p | |

| M:0 | F:0 | −0.425 | −2.185, 1.335 | 0.925 | 1.199 | 0.594 1.804 | <0.001 | −1.838 | −2.282, −1.374 | <0.001 |

| F:1 | F:0 | 2.424 | 1.086, 3.761 | <0.001 | 0.059 | −0.401 0.519 | 0.988 | 0.466 | 0.121, 0.811 | 0.003 |

| M:1 | F:0 | 2.077 | 0.13, 4.025 | 0.031 | −0.016 | −0.685 0.654 | 1 | 0.479 | −0.020, 0.979 | 0.066 |

| F:1 | M:0 | 2.849 | 0.982, 4.716 | 0.001 | −1.14 | −1.781 −0.498 | <0.001 | 2.294 | 1.814, 2.775 | <0.001 |

| M:1 | M:0 | 2.503 | 0.159, 4.846 | 0.031 | −1.214 | −2.02 −0.409 | 0.001 | 2.307 | 1.706, 2.908 | <0.001 |

| M:1 | F:1 | −0.346 | −2.391, 1.699 | 0.972 | −0.075 | −0.778 0.628 | 0.993 | 0.013 | −0.511, 0.537 | 0.999 |

References

- Gallup. LGBT Identification in U.S. Ticks up to 7.1%; Gallup: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dalia Research. Dalia-Studie Zu LGBT-Anteil in Der Bevölkerung-LGBT-Jetzt.De; Dalia Research: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, S.M. Global Recognition of Human Rights for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. Health Hum. Rights 2006, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Küpper, B.; Klocke, U.; Hoffmann, L.-C. Einstellungen Gegenüber Lesbischen, Schwulen und Bisexuellen Menschen in Deutschland; Antidiskriminierungsstelle Des Bundes: Baden-Baden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.; Ostergard, R.L. Measuring Discrimination against LGBTQ People: A Cross-National Analysis. Hum. Rts. Q. 2017, 39, 37–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweizer, K.; Brunner, F. Sexuelle Orientierungen. Bundesgesundheitsblatt-Gesundh. -Gesundh. 2013, 56, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffens, M.C.; Wagner, C. Diskriminierung von Lesben, Schwulen Und Bisexuellen. In Diskriminierung und Toleranz; VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermanns, S.; Graf, N.; Merz, S.; Stöver, H. »Wie Geht’s Euch?« Psychosoziale Gesundheit Und Wohlbefinden von LSBTIQ*; Beltz: Deutschland, Germany, 2021; ISBN 978-3-7799-6443-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chester, S.D.; Ehrenfeld, J.M.; Eckstrand, K.L. Results of an Institutional LGBT Climate Survey at an Academic Medical Center. LGBT Health 2014, 1, 327–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alencar Albuquerque, G.; De Lima Garcia, C.; Da Silva Quirino, G.; Alves, M.J.H.; Belém, J.M.; Dos Santos Figueiredo, F.W.; Da Silva Paiva, L.; Do Nascimento, V.B.; Da Silva Maciel, É.; Valenti, V.E.; et al. Access to Health Services by Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Persons: Systematic Literature Review. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2016, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennert, G.; Wolf, G. Gesundheit Lesbischer Und Bisexueller Frauen. Zugangsbarrieren Im Versorgungssystem Als Gesundheitspolitische Herausforderung. Fem. Polit.–Z. für Fem. Polit. 2009, 18, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, M.N.; Kanouse, D.E.; Burkhart, Q.; Abel, G.A.; Lyratzopoulos, G.; Beckett, M.K.; Schuster, M.A.; Roland, M. Sexual Minorities in England Have Poorer Health and Worse Health Care Experiences: A National Survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, T.; Nguyen, T.; Ryan, A.; Dwairy, A.; McCaffrey, J.; Yunus, R.; Forgione, J.; Krepp, J.; Nagy, C.; Mazhari, R.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Myocardial Infarction in the Transgender Population. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2019, 12, e005597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandfort, T.G.M.; de Graaf, R.; Bijl, R.V.; Schnabel, P. Same-Sex Sexual Behavior and Psychiatric Disorders. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2001, 58, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprowski, D.; Fischer, M.; Chen, X.; de Vries, L.; Kroh, M.; Kühne, S.; Richter, D.; Zindel, Z. Geringere Chancen Auf Ein Gesundes Leben Für LGBTQI*-Menschen. DIW Wochenber. 2021, 88, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haviland, K.; Swette, S.; Kelechi, T.; Mueller, M. Barriers and Facilitators to Cancer Screening Among LGBTQ Individuals With Cancer. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 2020, 47, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCabe, S.E.; Hughes, T.L.; Bostwick, W.B.; West, B.T.; Boyd, C.J. Sexual Orientation, Substance Use Behaviors and Substance Dependence in the United States. Addiction 2009, 104, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.; Semlyen, J.; Tai, S.S.; Killaspy, H.; Osborn, D.; Popelyuk, D.; Nazareth, I. A Systematic Review of Mental Disorder, Suicide, and Deliberate Self Harm in Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual People. BMC Psychiatry 2008, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, I.H. Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L.E.; Salway, T.; Tarasoff, L.A.; MacKay, J.M.; Hawkins, B.W.; Fehr, C.P. Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Among Bisexual People Compared to Gay, Lesbian, and Heterosexual Individuals:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Sex Res. 2018, 55, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, A.P.; Eliason, M.; Mays, V.M.; Mathy, R.M.; Cochran, S.D.; D’Augelli, A.R.; Silverman, M.M.; Fisher, P.W.; Hughes, T.; Rosario, M.; et al. Suicide and Suicide Risk in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations: Review and Recommendations. J. Homosex. 2011, 58, 10–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesbian, C.; Issues, T.H. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; ISBN 9780309210614. [Google Scholar]

- Brottman, M.R.; Char, D.M.; Hattori, R.A.; Heeb, R.; Taff, S.D. Toward Cultural Competency in Health Care: A Scoping Review of the Diversity and Inclusion Education Literature. Acad. Med. 2020, 95, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.; Cooper, R.L.; Ramesh, A.; Tabatabai, M.; Arcury, T.A.; Shinn, M.; Im, W.; Juarez, P.; Matthews-Juarez, P. Training to Reduce LGBTQ-Related Bias among Medical, Nursing, and Dental Students and Providers: A Systematic Review. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, S.; Gruber, C.; Ehlers, J.P.; Ramspott, S. Diversity in Medical Education. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2020, 37, Doc27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mews, C.; Schuster, S.; Vajda, C.; Lindtner-Rudolph, H.; Schmidt, L.E.; Bösner, S.; Güzelsoy, L.; Kressing, F.; Hallal, H.; Peters, T.; et al. Cultural Competence and Global Health: Perspectives for Medical Education—Position Paper of the GMA Committee on Cultural Competence and Global Health. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2018, 35, Doc28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obedin-Maliver, J.; Goldsmith, E.S.; Stewart, L.; White, W.; Tran, E.; Brenman, S.; Wells, M.; Fetterman, D.M.; Garcia, G.; Lunn, M.R. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender-Related Content in Undergraduate Medical Education. JAMA 2011, 306, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tollemache, N.; Shrewsbury, D.; Llewellyn, C. Que(e) Rying Undergraduate Medical Curricula: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Content Inclusion in UK Undergraduate Medical Education. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, A.A.; Southgate, E.; Rogers, G.; Duvivier, R.J. Inclusion of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex Health in Australian and New Zealand Medical Education. LGBT Health 2017, 4, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, M.Z.; France, K.; Kreider, E.F.; Wolfe-Roubatis, E.; Chen, K.D.; Wu, A.; Yehia, B.R. Comparing Medical, Dental, and Nursing Students’ Preparedness to Address Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Health. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, V.; Blondeau, W.; Bing-You, R.G. Assessment of Medical Student and Resident/Fellow Knowledge, Comfort, and Training with Sexual History Taking in LGBTQ Patients. Fam. Med. 2015, 47, 383–387. [Google Scholar]

- Parameshwaran, V.; Cockbain, B.C.; Hillyard, M.; Price, J.R. Is the Lack of Specific Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer/Questioning (LGBTQ) Health Care Education in Medical School a Cause for Concern? Evidence From a Survey of Knowledge and Practice Among UK Medical Students. J. Homosex. 2017, 64, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, S.; Jamieson, A.; Cross, H.; Nambiar, K.; Llewellyn, C.D. Medical Students’ Awareness of Health Issues, Attitudes, and Confidence about Caring for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Patients: A Cross-Sectional Survey. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, S.; Dettmer, S.; Wurl, W.; Seeland, U.; Maaz, A.; Peters, H. Evaluation of Curricular Relevance and Actual Integration of Sex/Gender and Cultural Competencies by Final Year Medical Students: Effects of Student Diversity Subgroups and Curriculum. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2020, 37, Doc19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szél, Z.; Kiss, D.; Török, Z.; Gyarmathy, V.A. Hungarian Medical Students’ Knowledge About and Attitude Toward Homosexual, Bisexual, and Transsexual Individuals. J. Homosex. 2020, 67, 1429–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leeuw, J.R. JsPsych: A JavaScript Library for Creating Behavioral Experiments in a Web Browser. Behav. Res. Methods 2014, 47, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedzich, D.A.; Bosinski, H.A. Sexualmedizin in Der Hausärztlichen Praxis: Gewachsenes Problembewusstsein Bei Nach Wie Vor Unzureichenden Kenntnissen. Sexuologie 2010, 17, 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, T.; Navarro, J.R.; Chen, E.H. An Institutional Approach to Fostering Inclusion and Addressing Racial Bias: Implications for Diversity in Academic Medicine. Teach. Learn. Med. 2020, 32, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbeisen, G.; Brandt, G.; Paslakis, G. A Plea For Diversity in Eating Disorders Research. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 820043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maduakolam, E.; Madden, B.; Kelley, T.; Cianciolo, A.T. Beyond Diversity: Envisioning Inclusion in Medical Education Research and Practice. Teach. Learn. Med. 2020, 32, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalantari, A.; Alvarez, A.; Chung, A.; Battaglioli, N.; Nwabueze, A.; Cooney, R.; Boehmer, S.; Gottlieb, M. 228 Sex and Racial Visual Representation in Emergency Medicine Textbooks: A Call to Action to Dismantle the Hidden Curriculum Against Diversity in Medicine. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2021, 78, S92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Reede, J.Y.; Jena, A.B. Addressing Workforce Diversity-A Quality-Improvement Framework. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D.L.; Supapannachart, K.J.; Caleon, R.L.; Ragmanauskaite, L.; McCleskey, P.; Yeung, H. Interactive Session for Residents and Medical Students on Dermatologic Care for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Patients. MedEdPORTAL J. Teach. Learn. Resour. 2021, 17, 11148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, K.; Abrams, M.P.; Khallouq, B.B.; Topping, D. Classroom Instruction: Medical Students’ Attitudes Toward LGBTQI + Patients. J. Homosex. 2021, 69, 1801–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Balbo, J.; Nottingham, K.; Forster, L.; Chavan, B. Student Journal Club to Improve Cultural Humility with LGBTQ Patients. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2020, 11, 2150132720963686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, M.D.; Mukherjee, S.M.; Goldsmith, C.A.W. Transgender Health Education for Pharmacy Students and Its Effect on Student Knowledge and Attitudes. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2021, 13, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minturn, M.S.; Martinez, E.I.; Le, T.; Nokoff, N.; Fitch, L.; Little, C.E.; Lee, R.S. Early Intervention for LGBTQ Health: A 10-Hour Curriculum for Preclinical Health Professions Students. MedEdPORTAL J. Teach. Learn. Resour. 2021, 17, 11072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silverberg, R.; Averkiou, P.; Servoss, J.; Eyez, M.; Martinez, L.C. Training Preclerkship Medical Students on History Taking in Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Patients. Transgender Health 2021, 6, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend. Arbeitsgruppe Inter- & Transsexualität Online Umfrage: Zur Aktuellen Situation Und Erfahrung von Trans* und Trans Sexuellen Erwachsenen, Jugendlichen Und Kindern Sowie Ihren Angehörigen; Das Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

| Group | Sex | Sexual History Taking | Physical Examination | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes/Rather Yes | No/Rather No | Yes/Rather Yes | No/Rather No | ||

| Heterosexual | Same | 93% | 7% | 97% | 3% |

| Other | 81% | 19% | 89% | 11% | |

| Homo-/bisexual | Same | 91% | 9% | 96% | 4% |

| Other | 88% | 22% | 94% | 6% | |

| Trans* | - | 82% | 18% | 88% | 12% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brandt, G.; Stobrawe, J.; Korte, S.; Prüll, L.; Laskowski, N.M.; Halbeisen, G.; Paslakis, G. Medical Students’ Perspectives on LGBTQI+ Healthcare and Education in Germany: Results of a Nationwide Online Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610010

Brandt G, Stobrawe J, Korte S, Prüll L, Laskowski NM, Halbeisen G, Paslakis G. Medical Students’ Perspectives on LGBTQI+ Healthcare and Education in Germany: Results of a Nationwide Online Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(16):10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610010

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrandt, Gerrit, Jule Stobrawe, Sophia Korte, Livia Prüll, Nora M. Laskowski, Georg Halbeisen, and Georgios Paslakis. 2022. "Medical Students’ Perspectives on LGBTQI+ Healthcare and Education in Germany: Results of a Nationwide Online Survey" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 16: 10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610010

APA StyleBrandt, G., Stobrawe, J., Korte, S., Prüll, L., Laskowski, N. M., Halbeisen, G., & Paslakis, G. (2022). Medical Students’ Perspectives on LGBTQI+ Healthcare and Education in Germany: Results of a Nationwide Online Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10010. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610010