The Lack of Ireland’s Assisted Human Reproduction (AHR) Regulation Viewed under the Lens of the Patient’s Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Ireland and AHR

1.2. AHR and Europe

- Investigate the experiences (positive and negative) of patients undergoing IVF/AHR within the Irish AHR system;

- Understand how Ireland’s current AHR regulation or lack of legislation has had an effect (if any) on the experiences of IVF/AHR patients.

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Pilot Study Design

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

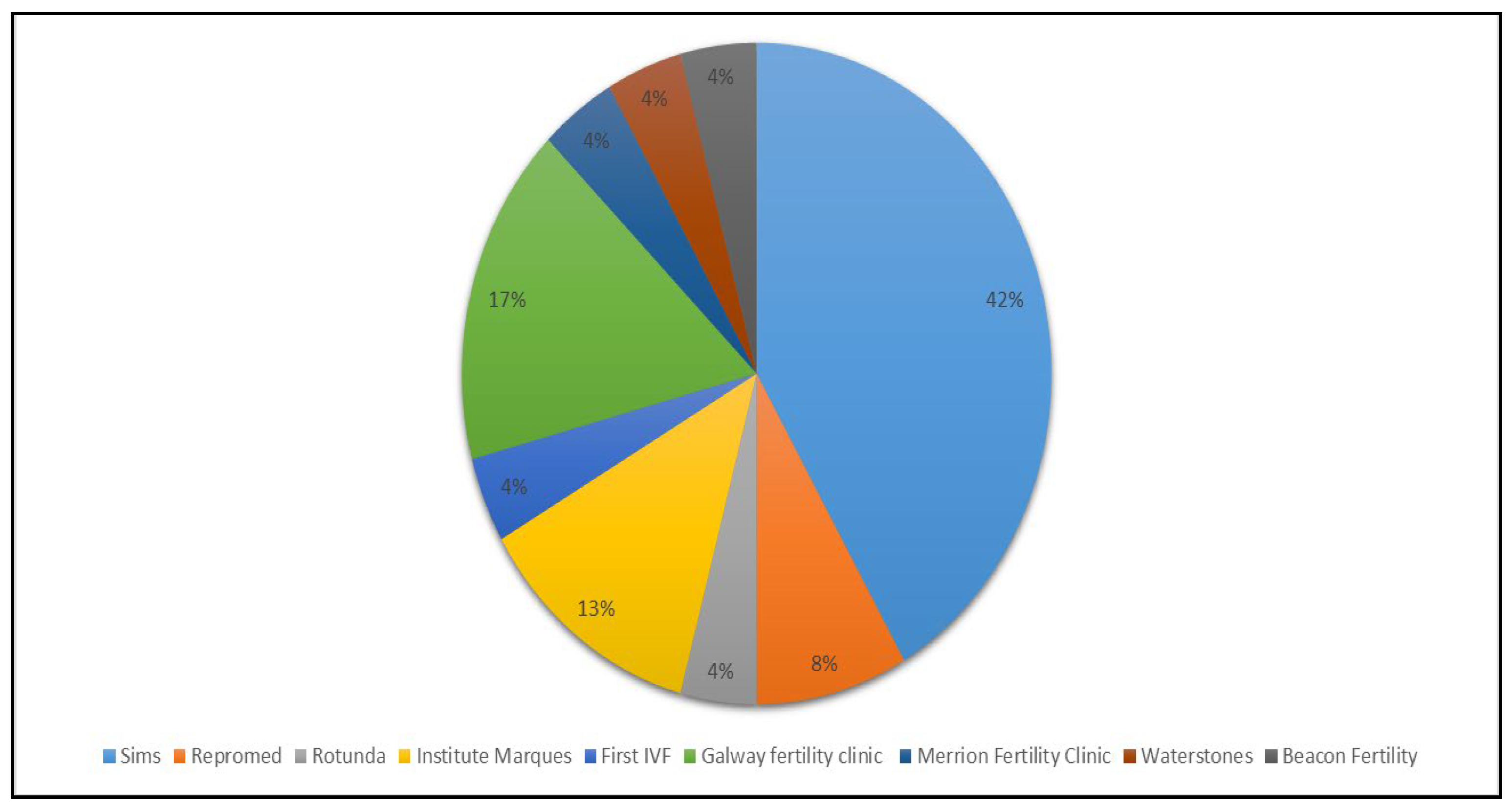

4.1. The Clinics Involved

4.2. Types of Treatments Undertaken

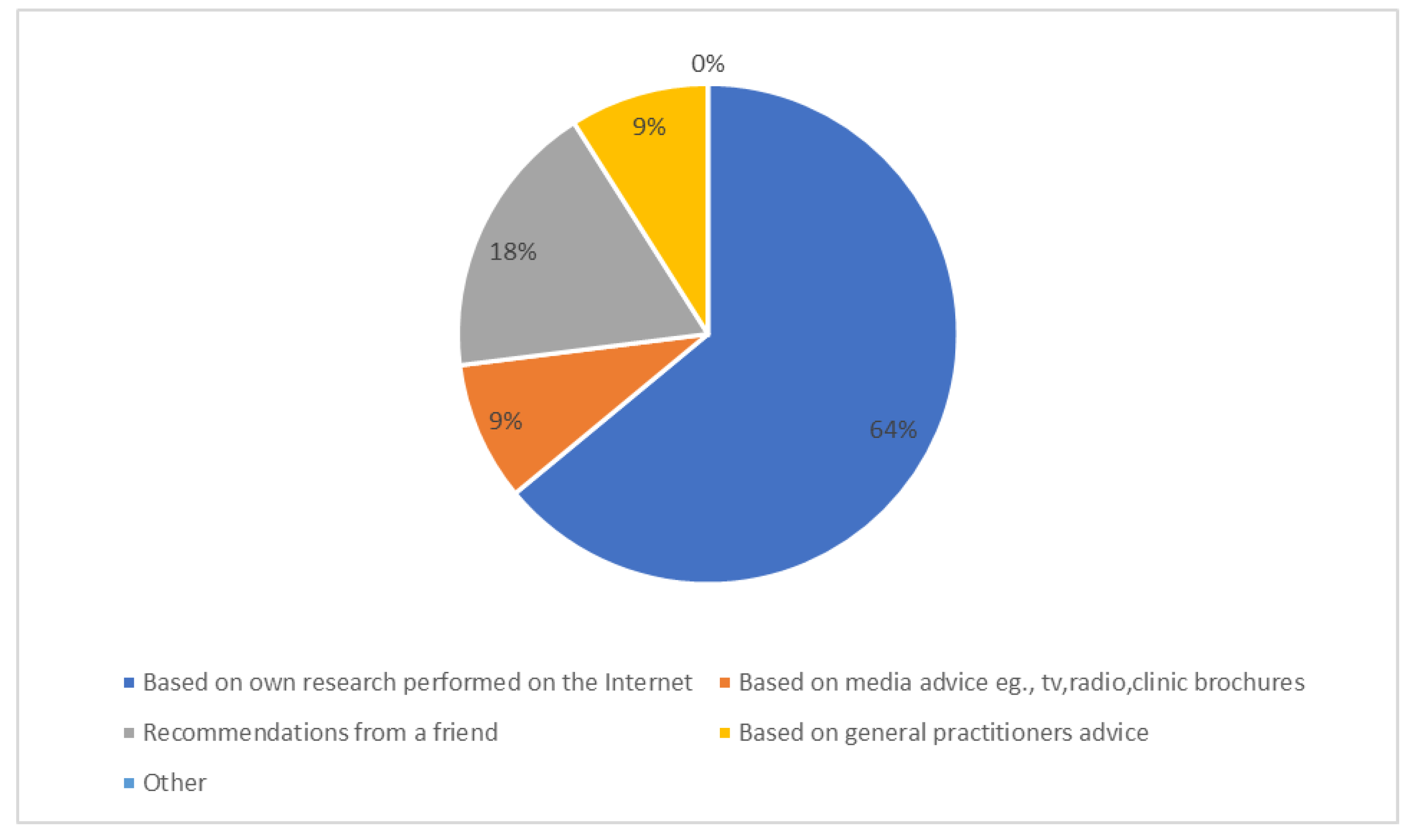

4.3. Reasons for Choosing a Particular Clinic

4.4. Amount of Money Spent on Treatments

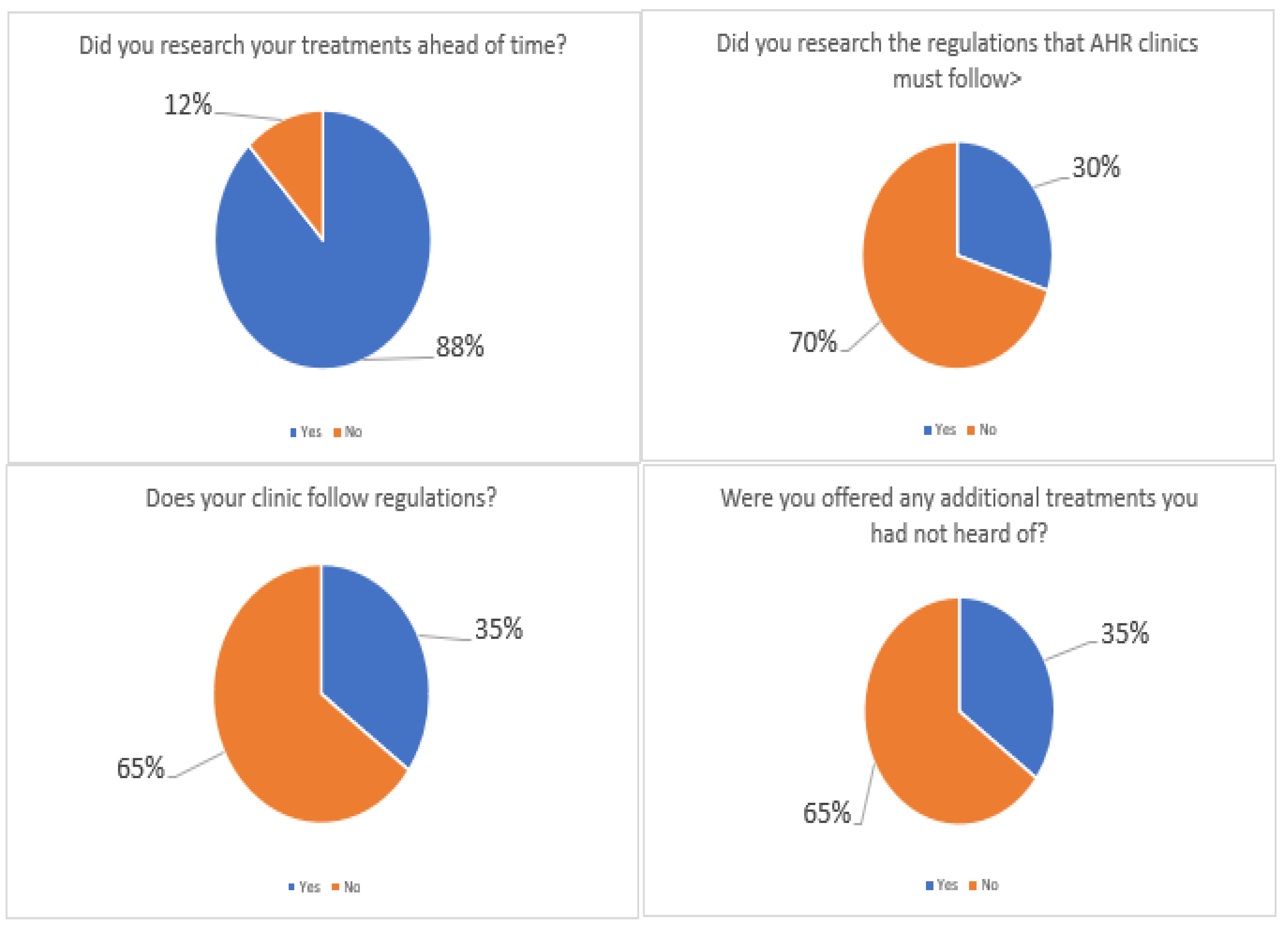

4.5. Knowledge of Treatments Undergone

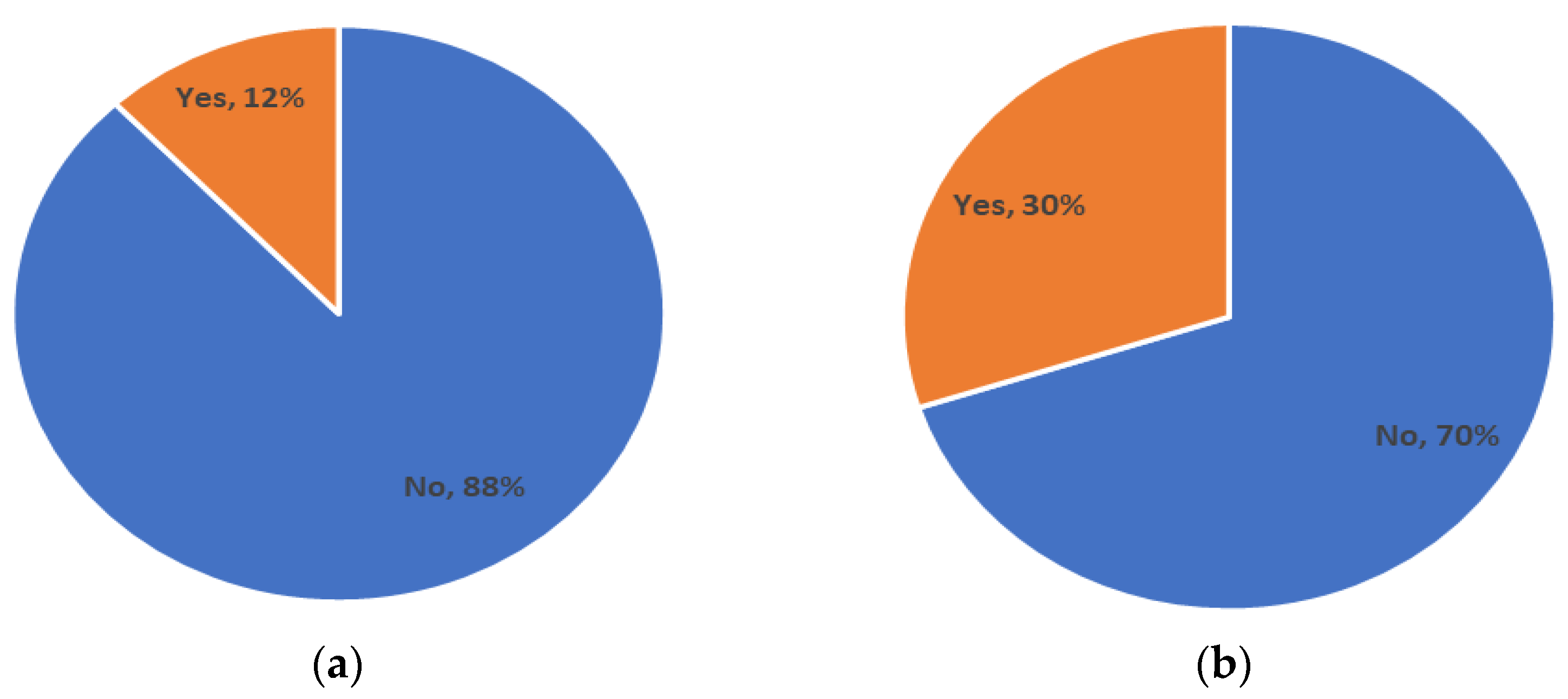

4.6. Awareness of Legislation around IVF/AHR

4.7. Information around Treatment and Success Rates

4.8. Criteria for Clinic Selection in Order of Importance

4.9. Improvement in Treatment

4.10. Experiences of the Overall Process

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mascarenhas, M.N.; Flaxman, S.R.; Boerma, T.; Vanderpoel, S.; Stevens, G.A. National, Regional, and Global Trends in Infertility Prevalence since 1990: A Systematic Analysis of 277 Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galhardo, A.; Cunha, M.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Psychological Aspects in Couples with Infertility. Sexologies 2011, 20, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzi, A.; Di Trani, M.; Solano, L.; Minutolo, E.; Tambelli, R. Success of Assisted Reproductive Technology Treatment and Couple Relationship: A Pilot Study on the Role of Romantic Attachment. Health Psychol. Open 2020, 7, 2055102920933073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, J. Enduring Politics: The Culture of Obstacles in Legislating for Assisted Reproduction Technologies in Ireland. Reprod. Biomed. Soc. Online 2016, 3, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Madden, D. Assisted Reproduction in the Republic of Ireland—A Legal Quagmire. In Ethics, Law and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 978-1-315-09433-5. [Google Scholar]

- IMC Medical Council—Guide to Professional Conduct & Ethics 8th Edition. Available online: https://www.medicalcouncil.ie/news-and-publications/reports/guide-to-professional-conduct-ethics-8th-edition.html (accessed on 26 June 2021).

- Walsh, D.J.; Ma, M.L.; Sills, E.S. The Evolution of Health Policy Guidelines for Assisted Reproduction in the Republic of Ireland, 2004–2009. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2011, 9, e019138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, E. Chapter 17—The Ireland Experience: Cultural and Political Factors Shaping the Development of Regulation of Assisted Human Reproduction, Ethical Status of Human Embryos, and Proposed Regulation of Surrogacy. In Human Embryos and Preimplantation Genetic Technologies; Sills, E.S., Palermo, G.D., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 141–152. ISBN 978-0-12-816468-6. [Google Scholar]

- Leahy, P. Officials Warn against ‘Double Standard’ on Commercial Surrogacy. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/social-affairs/officials-warn-against-double-standard-on-commercial-surrogacy-1.4786522 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Health Services Executive HSE. Available online: https://www2.hse.ie/conditions/child-health/fertility-problems-and-treatments/types-of-fertility-problems.html (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Calhaz-Jorge, C.; De Geyter, C.H.; Kupka, M.S.; Wyns, C.; Mocanu, E.; Motrenko, T.; Scaravelli, G.; Smeenk, J.; Vidakovic, S.; Goossens, V. Survey on ART and IUI: Legislation, Regulation, Funding and Registries in European Countries: The European IVF-Monitoring Consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, C. Explainer: When Will IVF Treatment Be Provided through the Irish Public Health Service? Available online: https://www.thejournal.ie/ivf-explainer-4942047-Dec2019/ (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- Book (eISB), Electronic I.S. Electronic Irish Statute Book (EISB). Available online: http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/cons/en/html (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Department of Health Cabinet Approval for Publication of Health (Assisted Human Reproduction) Bill. 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/5377c-cabinet-approval-for-publication-of-health-assisted-human-reproduction-bill-2022/#:~:text=Cabinet%20approval%20for%20publication%20of%20Health%20(Assisted%20Human%20Reproduction)%20Bill%202022,-From%20Department%20of&text=Minister%20for%20Health%20Stephen%20Donnelly,its%20presentation%20to%20the%20D%C3%A1il (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- McDermott, O.; Ronan, L.; Butler, M. A Comparison of Assisted Human Reproduction (AHR) in Ireland with Other Developed Countries. Reprod. Health 2022, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deech, R. Aims of the HFEA: Past and Future. Hum. Fertil. Camb. Engl. 1999, 2, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcome to the HFEA | Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority. Available online: https://www.hfea.gov.uk/ (accessed on 14 June 2021).

- Kelly, J.; Hughes, C.M.; Harrison, R.F. The Hidden Costs of IVF. Ir. Med. J. 2006, 99, 142–143. [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, M.; Gallo, F.; Hoorens, S.; Ledger, W. Assessing Long-Run Economic Benefits Attributed to an IVF-Conceived Singleton Based on Projected Lifetime Net Tax Contributions in the UK. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Early Days of IVF outside the UK|Human Reproduction Update | Oxford Academic. Available online: https://academic-oup-com.libgate.library.nuigalway.ie/humupd/article/11/5/439/605956?login=true (accessed on 27 June 2021).

- Ryan, J. The High, Mysterious and Added Costs of IVF. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/health-family/the-high-mysterious-and-added-costs-of-ivf-1.3845858 (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- NHS. IVF—Availability. Nhs.UK. 20 October 2017. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/ivf/availability/ (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- Cleveland Clinic IVF & Fertility Lab Information. Available online: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/departments/fertility/lab/about (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Mayo Clinic Intrauterine Insemination (IUI)—Mayo Clinic. Available online: https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/intrauterine-insemination/about/pac-20384722 (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Beacon Clinic Endometrial Function Test. Beac. CARE Fertil. Available online: https://www.beaconcarefertility.ie/treatments-services/tests-treatments/endometrial-function-test/ (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Waterstone Clinic Embryo Freezing—Waterstone Clinic—Ireland’s Leading Fertility Clinic. Waterstone Clin. Available online: https://waterstoneclinic.ie/treatments-care/cryopreservation-of-sperm-and-embryos/embryo-freezing/ (accessed on 23 July 2022).

- Stein, J.; Harper, J.C. Analysis of Fertility Clinic Marketing of Complementary Therapy Add-Ons. Reprod. Biomed. Soc. Online 2021, 13, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lensen, S.; Hammarberg, K.; Polyakov, A.; Wilkinson, J.; Whyte, S.; Peate, M.; Hickey, M. How Common Is Add-on Use and How Do Patients Decide Whether to Use Them? A National Survey of IVF Patients. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 36, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HPRA Blood and Tissues Establishments List. Available online: http://www.hpra.ie/homepage/blood-tissues-organs/blood-and-tissues-establishments-list (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law; Pennings, G.; de Wert, G.; Shenfield, F.; Cohen, J.; Tarlatzis, B.; Devroey, P. ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law 14: Equity of Access to Assisted Reproductive Technology. Hum. Reprod. Oxf. Engl. 2008, 23, 772–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oireactas Health (Assisted Human Reproduction) Bill 2022—No. 29 of 2022—Houses of the Oireachtas. Available online: https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/bills/bill/2022/29 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Charmaz, K.; Belgrave, L.L. Grounded Theory. In The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Forza, C. Survey Research in Operations Management: A Process-based Perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 152–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, H.L. Conducting Online Surveys. J. Hum. Lact. Off. J. Int. Lact. Consult. Assoc. 2019, 35, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis: Pearson New International Edition; Pearson Education Ltd.: Essex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, O.; Antony, J.; Sony, M.; Daly, S. Barriers and Enablers for Continuous Improvement Methodologies within the Irish Pharmaceutical Industry. Processes 2022, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunberg, P.H.; Da Costa, D.; Dennis, C.-L.; O’Connell, S.; Lahuec, A.; Zelkowitz, P. ‘How Did You Cope with Such Concerns?’: Insights from a Monitored Online Infertility Peer Support Forum. Hum. Fertil. 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, S.B.L.; Gelgoot, E.N.; Grunberg, P.H.; Schinazi, J.; Da Costa, D.; Dennis, C.-L.; Rosberger, Z.; Zelkowitz, P. ‘I Felt Less Alone Knowing I Could Contribute to the Forum’: Psychological Distress and Use of an Online Infertility Peer Support Forum. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2021, 9, 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, P. ‘Historic’ Bill to Allow Surrogacy to Take Place in State Approved by Cabinet. Available online: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/health/historic-bill-to-allow-surrogacy-to-take-place-in-state-approved-by-cabinet-1.4813581 (accessed on 29 May 2022).

- Wilkes, S.; Hall, N.; Crosland, A.; Murdoch, A.; Rubin, G. Patient Experience of Infertility Management in Primary Care: An in-Depth Interview Study. Fam. Pract. 2009, 26, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesi, R. Infertility and Its Treatment: An Emotional Roller Coaster. Aust. Fam. Physician 2005, 34, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkhowa, M.; Mcconnell, A.; Thomas, G.E. Reasons for Discontinuation of IVF Treatment: A Questionnaire Study. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, R. The Use of Adjuvants in Assisted Reproduction Treatment. Glob. Reprod. Health 2019, 4, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. Publicly-Funded IVF to Begin in 2023 with “Regional Fertility Hubs” before That. Available online: https://www.thejournal.ie/reproduction-5748209-Apr2022/ (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Walsh, D.J.; Sills, E.S.; Collins, G.S.; Hawrylyshyn, C.A.; Sokol, P.; Walsh, A.P. Irish Public Opinion on Assisted Human Reproduction Services: Contemporary Assessments from a National Sample. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 2013, 40, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Oireachtas, H. Of the Publications by the Houses of the Oireachtas—Houses of the Oireachtas. Available online: https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/publications?q=human+assisted+reproduction&date=&term=%2Fie%2Foireachtas%2Fhouse%2Fdail%2F32&fromDate=28%2F06%2F2021&toDate=28%2F06%2F2021&committee%5B0%5D=%2Fen%2Fcommittees%2F32%2Fcommittee-on-health%2F&topic%5B0%5D=reports&topic%5B1%5D=reports%2Creports (accessed on 28 June 2021).

- De Geyter, C.; Calhaz-Jorge, C.; Kupka, M.S.; Wyns, C.; Mocanu, E.; Motrenko, T.; Scaravelli, G.; Smeenk, J.; Vidakovic, S.; Goossens, V.; et al. ART in Europe, 2014: Results Generated from European Registries by ESHRE: The European IVF-Monitoring Consortium (EIM) for the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 1586–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Survey Design Steps | Procedures |

|---|---|

| Select the variables/indicators to represent the concepts and measurement scale | The variables were identified in the literature review based on studies about AHR participants and regulatory environments. |

| Define target population and sampling frame | The aim is to carry out a pilot test for a study on the target population to investigate the experiences (positive and negative) of undergoing IVF/AHR within the Irish AHR system. |

| Determining question types, format, and sequence | The questionnaire was designed with open and closed questions and divided into two sections. The first one was related to the respondents’ profile and other demographic information. The second part was focused on the investigation of the experiences (positive and negative) of patients undergoing IVF/AHR within the Irish AHR system. Additionally, this section focused on factors affecting treatment selection, and choice of IVF centre as well as knowledge of legislation and rights. |

| Pretesting the questionnaire | The pre-testing was carried out with six people undergoing AHR as well as with two academics to cover both theoretical and practical aspects of AHR treatment in Ireland. The objective was for respondents to indicate difficulty in completing, responding or lack of questions or in the sequence of questions. |

| Report | The analysis of the questionnaire allowed preliminary analysis on the experiences of patients undergoing IVF/AHR within the Irish AHR system and an understanding of how Ireland’s current AHR regulation or lack of legislation has had an effect (if any) on the experiences of IVF/AHR patients. |

| What clinic did you attend? Tick as appropriate A list of all Irish clinics was provided |

| What treatment did you have? Tick as appropriate or comment A list of treatments was provided |

| Why did you choose this clinic? Tick as appropriate A list of reasons for choosing clinics was provided |

| What research did you do? Tick as appropriate A list of research types was provided |

| Approximately how much have you spent in total on AHR treatment? A range of costs was provided |

| Did you research the treatment that you were going to have? Yes/No |

| Did you research any regulations that AHR clinics must follow? Yes/No |

| Do you know if your selected clinic follows these regulations? Yes/No |

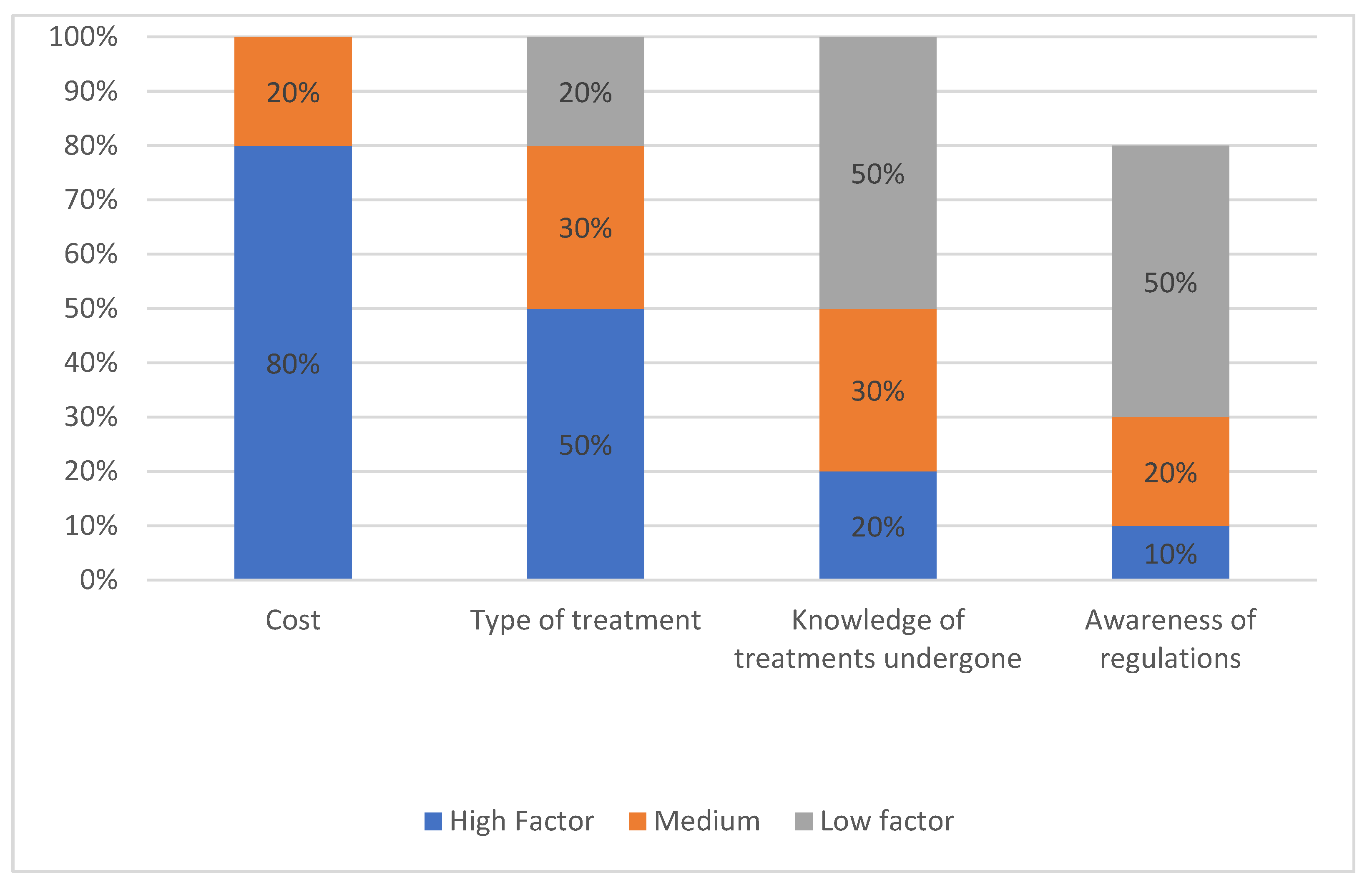

| Please rank the following criteria for clinic selection (Cost, type of treatment required, knowledge of treatments and awareness of regulations) in terms of choosing a clinic as to whether they were of high, medium, or low importance to you? |

| Were you offered any additional treatments of which you had not heard? Yes/No |

| Are you aware that there is a proposed bill with the Irish government to regulate AHR clinics? Yes/No |

| If you have read or are aware of this bill, do you think it would have improved your treatment/experience had it been implemented? Yes/No |

| Are you aware that Ireland is one of the only EU countries that do not have regulations around AHR clinics? Yes/No |

| Do you think the laws do enough to protect AHR patients? Yes/No/Do not know. |

| Do you think you were well informed of the treatment success rate, procedure and expected results before you had your treatment? Yes/No/Not sure |

| Do you think there are any improvements or clarifications that need to be made immediately? Please comment |

| How would you describe your experience in an AHR clinic overall? Please comment |

| IVF Clinic Selection Factors | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|

| Cost | 0.852 |

| Type of treatment | 0.835 |

| Knowledge of treatments undergone | 0.773 |

| Awareness of regulations | 0.701 |

| “Excellent experience, I have a 3 year old son as a result that I never would have had” |

| “Stressful” |

| “Has been more difficult with COVID-19 as I have not met my fertility doctor” |

| “Extremely expensive as a patient I was not given the holistic level of care needed” |

| “My experience of my current clinic in Spain has been far more superior than in Ireland” |

| “Overall good and I did have a son thanks to them” |

| “Really poor experience however the clinic I am currently with seems a lot better and I feel looked after and cared for as an individual” |

| “Lack of a case management approach, means the patient has to be to be their own case manager, overall, a stressful experience” |

| “A nerve wrecking experience and I am a nurse so feel I have some insight from a medical point of view, the experience would have been so much worse otherwise” |

| “Very reassuring and informative” |

| “Always found the clinic friendly and set us at ease” |

| “Hidden costs led us to feel unsure of our clinic as we paid a large bill and 2 months later got another one, very frustrating and upsetting as it so expensive “ |

| “I have had a positive experience so far but still feel like a “rabbit in the headlights” as there is always something else I should have been aware of “ |

| “OK but extremely stressful, lots of unnecessary waiting on results” |

| “Dismissive of me and not very investigative or informed. I had to point out information and facts out from my own research” |

| “I cannot fault my clinic” |

| “Communication from the clinic can be poor at times” |

| “The clinic staff were generally nice but you were very much a number” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ronan, L.; McDermott, O.; Butler, M.; Trubetskaya, A. The Lack of Ireland’s Assisted Human Reproduction (AHR) Regulation Viewed under the Lens of the Patient’s Experience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9534. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159534

Ronan L, McDermott O, Butler M, Trubetskaya A. The Lack of Ireland’s Assisted Human Reproduction (AHR) Regulation Viewed under the Lens of the Patient’s Experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9534. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159534

Chicago/Turabian StyleRonan, Lauraine, Olivia McDermott, Mary Butler, and Anna Trubetskaya. 2022. "The Lack of Ireland’s Assisted Human Reproduction (AHR) Regulation Viewed under the Lens of the Patient’s Experience" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9534. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159534

APA StyleRonan, L., McDermott, O., Butler, M., & Trubetskaya, A. (2022). The Lack of Ireland’s Assisted Human Reproduction (AHR) Regulation Viewed under the Lens of the Patient’s Experience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9534. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159534