Existential and Spiritual Attitudes of Polish Medical and Nursing Staff towards Death

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Fear of Death (FD) related to questions about numbers 1, 2, 7, 18, 20, 21, 32, which contained the statements: death is undoubtedly an unpleasant experience; the prospect of my death raises anxiety in me; it worries me that death is inevitable; I am very afraid of death; I am terrified that death will mean the end of everything that I know; I am worried about the uncertainty about what will happen after death.

- Death Avoidance (DA) included questions 3, 10, 12, 19, 26, with the statements: I avoid the thought of death at all costs; whenever a thought occurs in my head about death, I try to push it away; I try not to think about death; I completely avoid thinking about death; I try to have nothing to do with the subject of death.

- Neutral Acceptance (NA) including questions 6, 14, 17, 24, 30 with statements: death should be seen as a natural, undeniable and unavoidable event; death is a natural aspect of life; I am not afraid of death but I am not waiting for death; death is part of life as a process; death is neither good nor bad.

- Approach Acceptance (AA) with questions about numbers 4, 7,13, 15, 16, 22, 25, 27, 28, 31, where the statements were placed: I believe that I will be in heaven after death; death joins with entering the state of greatest satisfaction; I believe that heaven will be a much better place than this world; death is a union with God and eternal happiness; death brings the promise of a new and wonderful life; after death I expect to meet again with those whom I love; I see death as a transition to eternal and blessed place; death releases my soul; the only thing that gives me relief in the face of death is faith in life after death; I expect a new life after death.

- Escape Acceptance (AE) with questions 5, 9, 11, 23, 29, including statements: death will end all my problems; death is an escape from this cruel world; death is delivery from pain and suffering; death is liberation from earthly suffering; I see death as a release from the burden of life.

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brusiło, J. Cierpienie człowieka jako konstytutywny element natury ludzkiej. Przyczynek do antropologii personalistycznej. Med. Prakt. 2007, 8, 241–244. [Google Scholar]

- Sleziona, M.; Krzyżanowski, D. Postawy pielęgniarek wobec śmierci i umierania. Piel. Zdr. Publ. 2011, 1, 217–223. [Google Scholar]

- Mogodi, M.S.; Kebaetse, M.B.; Molwantwa, M.C.; Prozesky, D.R.; Griffiths, D. Using a virtue ethics lens to develop a socially accountable community placement programme for medical students. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowak, A.J. Identyfikacja Postaw; Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski, KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2000; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Hye-Young, K.; Sung-Joong, K.; Young-Ran, Y. Relationship between Death Anxiety and Communication Apprehension with the Dying. Int. J. Bio-Sci. Bio-Technol. 2016, 8, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-García, C.; Fernández-Alcántara, M.; Schmidt-Riovalle, J.; Cruz-Quintana, F.; García-Caro, M.P.; Pérez-García, M. Specific emotional schema of death-related images vs unpleasant images/Esquema emocional específico de imágenes relacionadas con la muerte frente a imágenes desagradables. Estud. Psicol. 2017, 38, 689–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.A. Associations Between End-of-Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care Near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment. JAMA 2008, 300, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sweat, M.T. What Are the Spiritual Needs Associated with Grief? J. Christ Nurs. 2017, 34, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, M.L.R.; Almeida, H.G.; Esmeraldo, J.D.; Nobre, C.B.; Pinheiro, W.R.; de Oliveira, C.R.T.; Sousa, I.D.C.; Lima, O.M.M.L.; Lima, N.N.R.; Moreira, M.M.; et al. When health professionals look death in the eye: The mental health of professionals who deal daily with the 2019 coronavirus outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-del-Río, A.; Ortega-García, E.; Oñate-Ocaña, L.; Vargas-Huicochea, I. Experience of oncology residents with death: A qualitative study in Mexico. BMC Med. Ethics. 2019, 20, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zdziarski, K.; Awad, M.; Landowski, M.; Zabielska, P.; Karakiewicz, B. Attitudes of Palestinian and Polish Medical Students Towards Death. OMEGA (Westport) 2020, 0030222820966248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, M.; Linnard-Palmer, L.; Ganley, B.; Catolico, O.; Phillips, W. Evaluating the Use of Standardized Patients in Teaching Spiritual Care at the End of Life. Clin. Simul. Nursing Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2014, 10, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, K.I.; Zdziarski, K. Attitudes of Polish-Speaking and English-Speaking Medical Students towards Death During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Educ. Health Sport 2021, 11, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-El-Noor, N.I.; Abu-El-Noor, M.K. Attitude of Palestinian Nursing Students Toward Caring for Dying Patients. J. Holist. Nurs. 2015, 34, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudek, P.J.; Sekowski, M.; Steuden, S. Polish Adaptation of the Death Attitude Profile—Revised. OMEGA (Westport) 2018, 81, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Thom, B.; Kline, N.E. Assessing Nurses’ Attitudes Toward Death and Caring for Dying Patients in a Comprehensive Cancer Center. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2008, 35, 955–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Steimer, T. The Biology of Fear and Anxiety-Related Behaviors. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2002, 4, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cozzolino, P.J.; Blackie, L.E.R.; Meyers, L.S. Self-Related Consequences of Death Fear and Death Denial. Death Stud. 2013, 38, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lynn, T.; Curtis, A.; Lagerwey, M.D. Association Between Attitude Toward Death and Completion of Advance Directives. OMEGA (Westport) 2016, 74, 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, C.Y.; Ha, N.H.L.; Tan, L.L.C.; Low, J.A. Attitudes towards the dying and death anxiety in acute care nurses—Can a workshop make any difference? A mixed-methods evaluation. Palliat. Support. Care 2020, 18, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiaohong, G.; Ruishuang, Z. Assessing oncology nurses’ attitudes towards death and the prevalence of burnout: A cross-sectional study. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 42, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.D.; Reed, C.H.M.; Adams, C.M. Death Attitudes, Palliative Care Self-efficacy, and Attitudes Toward Care of the Dying Among Hospice Nurses. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2021, 28, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, W.E.; Hope, S.; Matzo, M. Palliative Nursing and Sacred Medicine: A Holistic Stance on Entheogens, Healing, and Spiritual Care. J. Holist. Nurs. 2019, 37, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glińska, J.; Szczepaniak, M.; Lewandowska, M.; Brosowska, B.; Dziki, A.; Dziki, Ł. The attitude of medical staff in the face of dying. J. Pub. Health Nurs. Med. Rescue 2012, 3, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo, J.C.; Villacieros, M.; Hassoun, H. Actitudes hacia el cuidado de pacientes al final de la vida y miedo a la muerte en una muestra de estudiantes sociosanitarios. Med. Paliativa 2018, 25, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres Rivera, D.I.; Cristancho Zambrano, L.Y.; López Romero, L.A. Attitudes of Nurses towards the Death of Patients in an Intensive. Rev. Cienc. Salud 2019, 17, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Staff Surveyed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | Nursing | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Women | 69 | 62.7 | 84 | 76.4 |

| Men | 41 | 37.3 | 26 | 23.6 |

| Age of Respondents | ||||

| Up to 30 years | 60 | 54.5 | 107 | 97.3 |

| Over 30 years | 50 | 45.5 | 3 | 3.7 |

| Dimensions of Death | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Descriptive Statistics for Specific Dimensions of Death | |||||

| Fear of Death | Death Avoidance | Neutral Acceptance | Approach Acceptance | Escape Acceptance | |

| M ± SD | 30.1 ± 9.8 | 17.7 ± 7.5 | 27.6 ± 5.2 | 41.5 ± 15.0 | 19.9 ± 7.7 |

| Me | 29.0 | 17.0 | 28.0 | 42.5 | 19.0 |

| Min–Max | 10.0–49.0 | 5.0–35.0 | 11.0–35.0 | 10.0–70.0 | 5.0–35.0 |

| Coefficient of Variation | 32.7 | 42.6 | 18.9 | 36.1 | 38.7 |

| Slant | 0.2 | 0.4 | −0.6 | −0.4 | 0.3 |

| Descriptive statistics for medical staff | |||||

| M ± SD | 29.2 ± 10.2 | 17.1 ± 7.6 | 27.1 ± 5.8 | 42.8 ± 15.1 | 19.7 ± 7.7 |

| Me | 28.5 | 16.0 | 28.0 | 44.0 | 20.0 |

| Min-Max | 10.0–49.0 | 5.0–35.0 | 11.0–35.0 | 10.0–70.0 | 5.0–35.0 |

| Descriptive statistics for nursing staff | |||||

| M ± SD | 30.9 ± 9.4 | 18.3 ± 7.5 | 28.0 ± 4.5 | 40.1 ± 14.8 | 20.1 ± 7.8 |

| Me | 30.5 | 18.0 | 28.0 | 41.0 | 19.0 |

| Min-Max | 13.0–49.0 | 5.0–35.0 | 17.0–35.0 | 11.0–66.0 | 5.0–35.0 |

| Dimensions of Death | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fear of Death | Death Avoidance | Neutral Acceptance | Approach Acceptance | Escape Acceptance | ||

| Fear of Death | r | 1.000 | 0.556 | −0.272 | 0.366 | 0.056 |

| t | 9.887 | −4.179 | 5.696 | 0.822 | ||

| p | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.412 | ||

| Death Avoidance | r | 0.556 | 1.000 | −0.302 | 0.298 | 0.113 |

| t | 9.887 | −4.684 | 4.615 | 1.672 | ||

| p | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.096 | ||

| Neutral Acceptance | r | −0.272 | −0.302 | 1.000 | −0.166 | 0.107 |

| t | −4.179 | −4.684 | −2.481 | 1.587 | ||

| p | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.014 | 0.114 | ||

| Approach Acceptance | r | 0.366 | 0.298 | −0.166 | 1.000 | 0.380 |

| t | 5.696 | 4.615 | −2.481 | 6.060 | ||

| p | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.014 | 0.000 | ||

| Escape Acceptance | r | 0.056 | 0.113 | 0.107 | 0.380 | 1.000 |

| t | 0.822 | 1.672 | 1.587 | 6.060 | ||

| p | 0.412 | 0.412 | 0.114 | 0.000 | ||

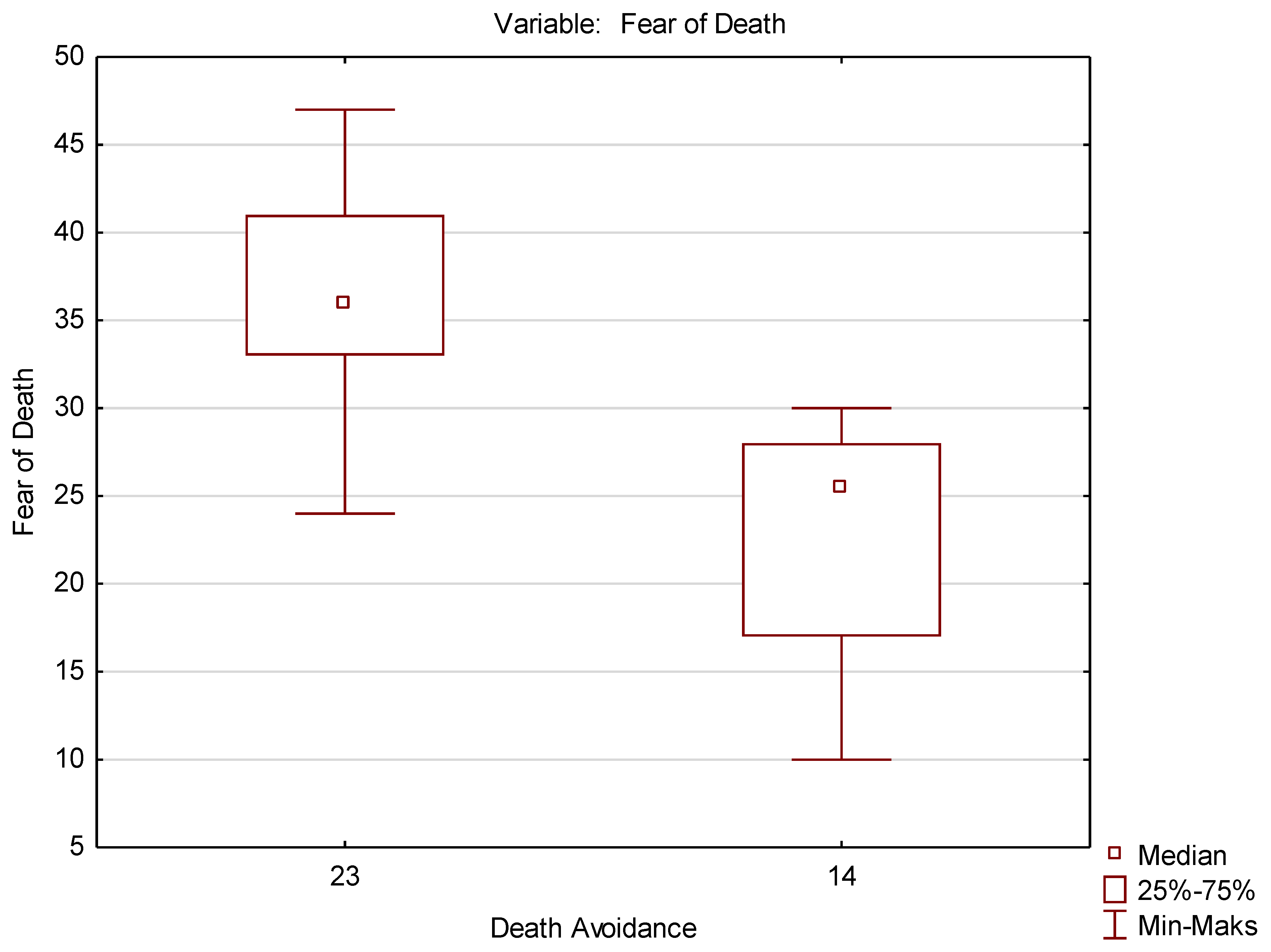

| Variable | Mann–Whitney U test (Continuity Corrected) (% of Variables) Relative to the Variable: Death Avoidance. The Results are Significant with p < 0.05000. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum. Rang Group 1 | Sum. Rang Group 2 | U | Z | p | Z Revised | p | N Group 1 | N Group 2 | |

| Fear of Death | 168.0000 | 63.00000 | 8.000000 | 3.274431 | 0.001059 | 3.276560 | 0.001051 | 11 | 10 |

| Variable | Mann-Whitney U test (Continuity Corrected) (% of Variables) Relative to the Variable: Death Avoidance. The Results are Significant with p < 0.05000. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sum. Rang Group 1 | Sum. Rang Group 2 | U | Z | p | Z Revised. | p | N Group 1 | N Group 2 | |

| Fear of Death | 65.5000 | 144.5000 | 20.5000 | −2.16525 | 0.030369 | −2.17015 | 0.029996 | 9 | 11 |

| Factor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| T4 | 0.80 | ||||

| T8 | 0.58 | ||||

| T13 | 0.78 | ||||

| T15 | 0.82 | ||||

| T16 | 0.82 | ||||

| T22 | 0.71 | ||||

| T25 | 0.84 | ||||

| T27 | 0.63 | ||||

| T28 | 0.77 | ||||

| T31 | 0.78 | ||||

| T1 | * | ||||

| T2 | 0.68 | ||||

| T7 | 0.78 | ||||

| T17 | * | ||||

| T18 | 0.67 | ||||

| T20 | 0.58 | ||||

| T21 | 0.81 | ||||

| T32 | 0.76 | ||||

| T5 | 0.59 | ||||

| T9 | 0.76 | ||||

| T11 | 0.68 | ||||

| T23 | 0.72 | ||||

| T29 | 0.80 | ||||

| T6 | 0.60 | ||||

| T14 | 0.84 | ||||

| T24 | 0.80 | ||||

| T3 | 0.62 | ||||

| T10 | 0.66 | ||||

| T12 | 0.75 | ||||

| T19 | 0.78 | ||||

| T26 | 0.51 | ||||

| T30 | * | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zdziarski, K.; Zabielska, P.; Wieder-Huszla, S.; Bąk, I.; Cheba, K.; Głowacka, M.; Karakiewicz, B. Existential and Spiritual Attitudes of Polish Medical and Nursing Staff towards Death. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159461

Zdziarski K, Zabielska P, Wieder-Huszla S, Bąk I, Cheba K, Głowacka M, Karakiewicz B. Existential and Spiritual Attitudes of Polish Medical and Nursing Staff towards Death. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159461

Chicago/Turabian StyleZdziarski, Krzysztof, Paulina Zabielska, Sylwia Wieder-Huszla, Iwona Bąk, Katarzyna Cheba, Mariola Głowacka, and Beata Karakiewicz. 2022. "Existential and Spiritual Attitudes of Polish Medical and Nursing Staff towards Death" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159461

APA StyleZdziarski, K., Zabielska, P., Wieder-Huszla, S., Bąk, I., Cheba, K., Głowacka, M., & Karakiewicz, B. (2022). Existential and Spiritual Attitudes of Polish Medical and Nursing Staff towards Death. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9461. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159461