Challenges and Opportunities for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in the COVID-19 Response in Africa: A Mixed-Methods Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection

- 1.

- Assessing Need

- 2.

- Coordinating Action

- 3.

- Delivering Support

- 4.

- Monitoring and Evaluation

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Quantitative Analysis

2.3.2. Qualitative Analysis

- Thematic, including issues relating to programming and coordination, public health system, capacity in public mental health, resources, and existing guidance;

- Descriptive, notably around contextual information and stakeholder relationships;

- Informative, focusing on insights from the informants’ experiences, such as lessons learned, suggestions and recommendations, and best practices;

- Assessment, dealing with evaluative data such as positive, opportunity, enabler, facilitators; negative, challenge, constraint, gap, barriers; low/high priority.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

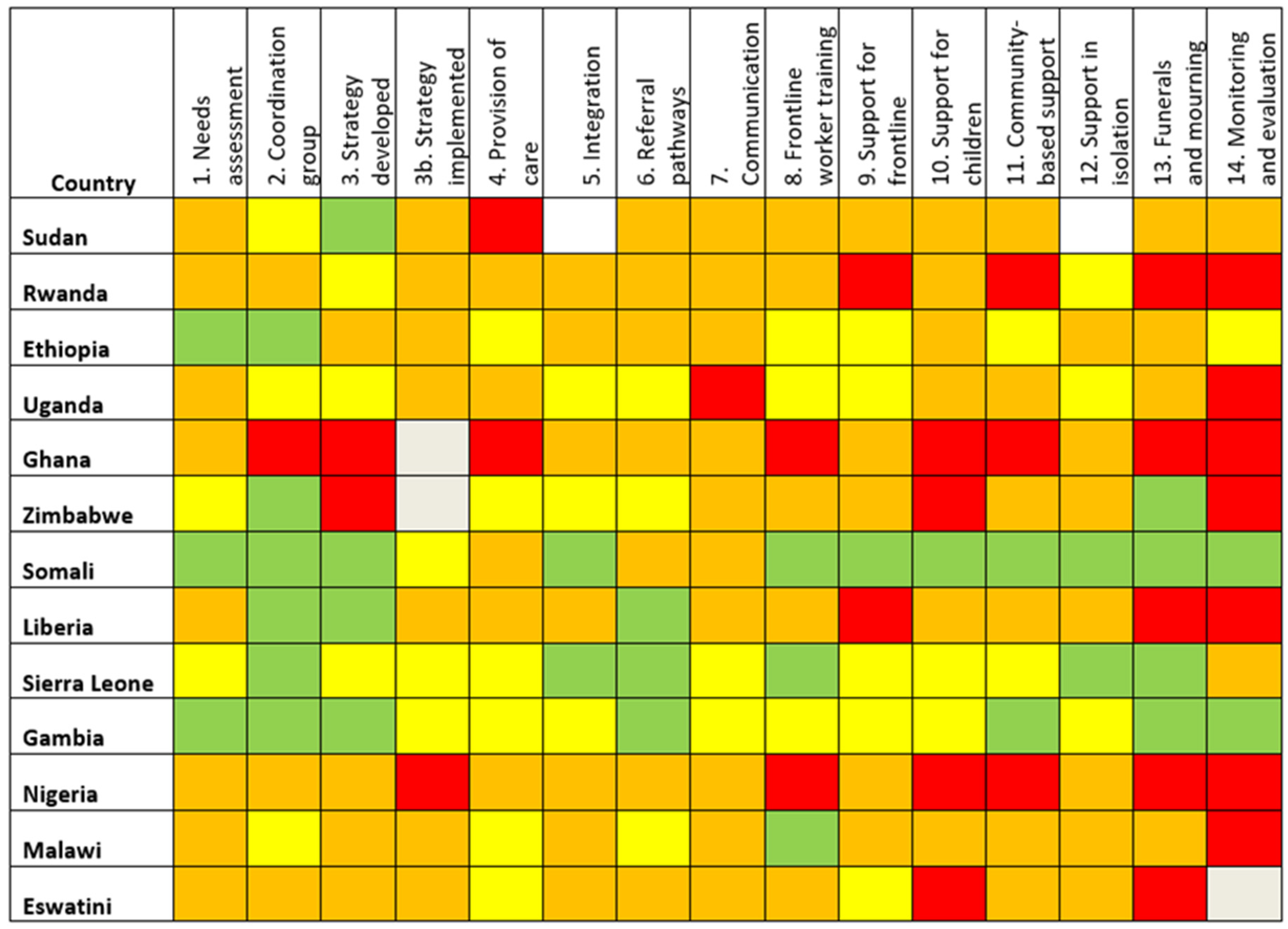

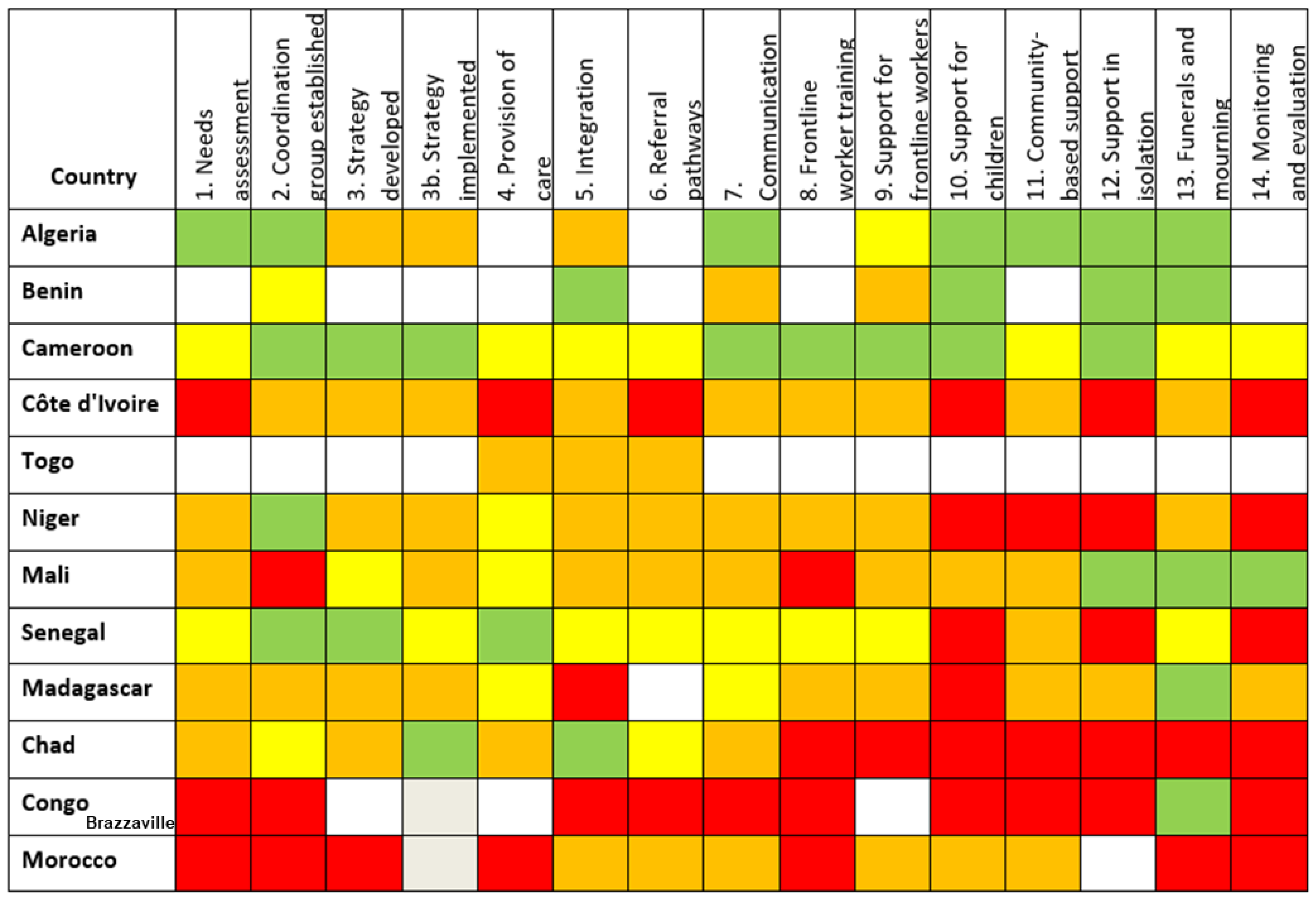

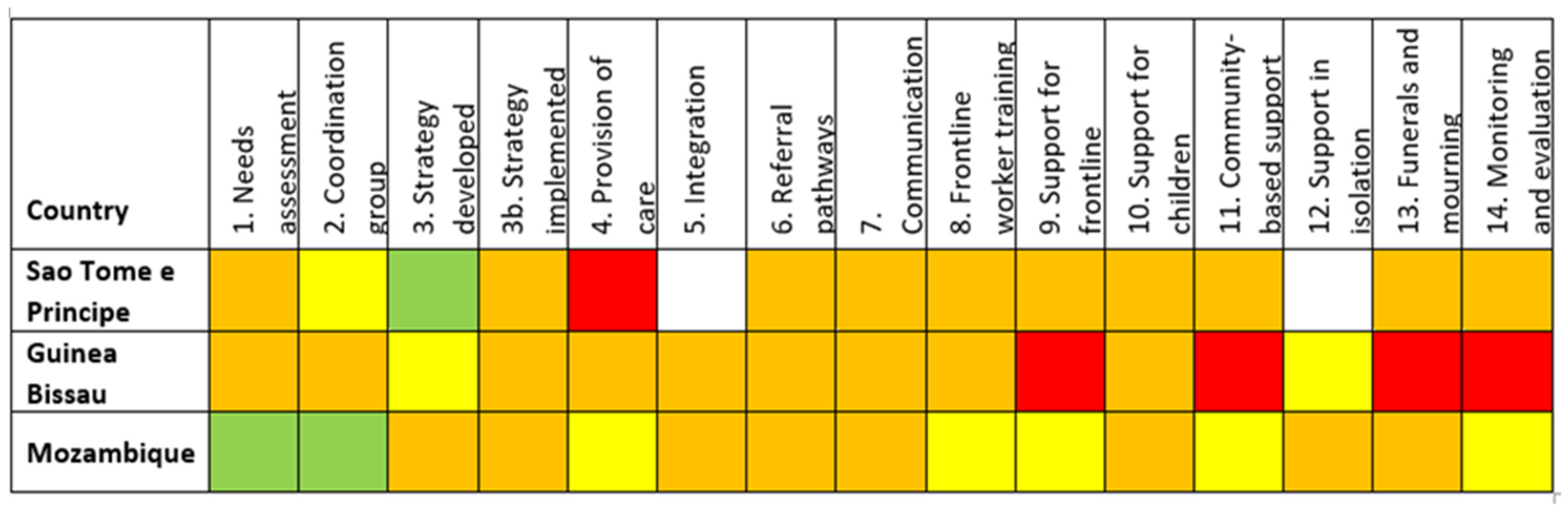

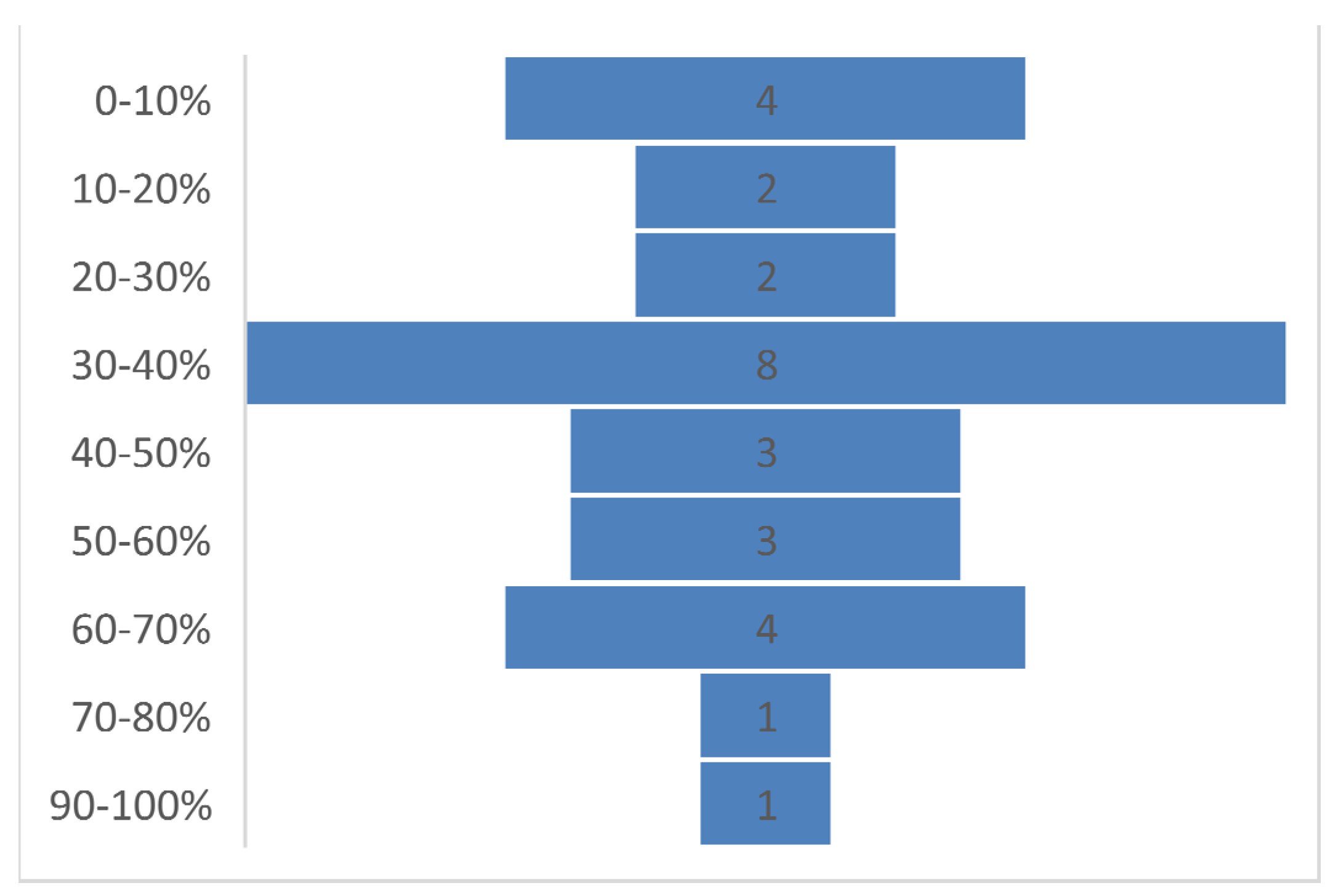

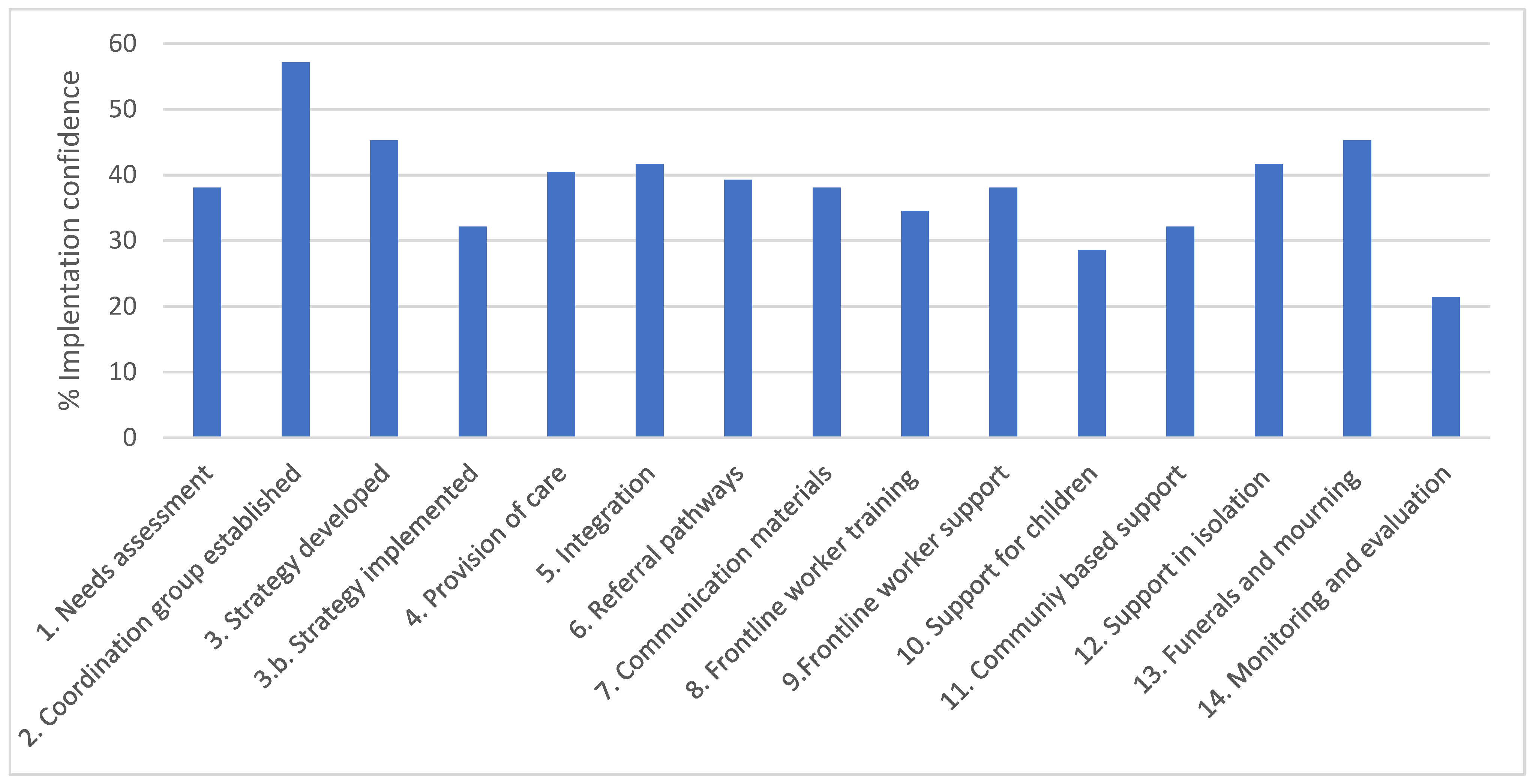

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Challenges to Improving MHPSS Components in Crisis Response

Lack of Political Commitment and Engagement

“We’venot got so many people who would want to take lead in managing mental health programmes at different levels. (…) When my colleagues were in quarantine, we looked for someone to take over as we rest maybe for a week or two and we could not find anyone”.[MoH Mental Health (MH) focal point]

Low Prioritisation of Mental Health within Emergency Response Structures

“They prioritisecase management, infection prevention …, making sure everything else was ready but mental health was not given the priority with that, thus no fund was allocated to it”.[MoH MH focal point]

Lack of Institutional Memory and Failure to Apply Lessons Learned

“We havenot been able to take advantage of the past. There is still difficulty in giving the right place to mental health in the response to the COVID-19”.[Civil society representative]

“We usedsome of the systems and structures that were put in place for Ebola, but we clearly ignored some of them or flagrantly neglected to uphold some of them”.[Civil society representative]

Lack of Funding

“These partnerscome on board when there’s an immense emergency, there is a pandemic, when there is a disaster. After that...they all leave and go away on different programmes and we struggle on our own”.[MoH MH focal point]

“Even thefunding that we have with WHO never came as funding for mental health in COVID. It comes as just the COVID response in particular targeting case management, IPC and the like”.[WHO MH focal point]

“Donors’ contributionsform a significant proportion of our overall budget and [when COVID-19 hit] no donor at the time had COVID activities planned. They all had different healthcare issues or projects that they were meant to support. But then COVID came as an unexpected thing. It wasn’t easy to have people repurpose money in the very beginning. And while we were going through all the bureaucracies to have that done, the virus was spreading in the communities and the government was still begging people here and there”.[Civil society representative]

Information Systems and Reporting

“We didn’thave enough mental health indicators collected or people trained on how to fill this indicator, so we had inadequate data collection and reporting, so what you are getting—the reports we are getting [do not represent] a true picture of what’s going on in the ground”.[MoH MH focal point]

Human Resources Challenges

“The humanresources (…) who were trained on mental health were doing other things, like you’d find the [district] focal person for mental health is working in the antenatal clinic or is working in paediatrics, and is not there offering mental health support because they’re doing routine work”.[MoH MH focal point]

“Mentalhealth clinicians [are paid] little money and sometimes not paid at all, as compared to nurses and other people that were working in the same area. It was very noticeable, and it was demotivating for our colleagues in mental health…”.[Civil society representative]

“In our teampsychologists are not integrated in the health system…they are volunteer, they have left their job in order to help the population…It is very important for us to have means to support them so that they will continue it”.[MoH MH focal point]

“The trainingof the primary healthcare workers is also very medicalised. They are not trained in basic kinds of psychological, psychosocial skills to make the person feel comfortable, you know, get the most out of the person as possible”.[Civil society representative]

“In someareas, we actually train healthcare workers in the delivery of psychosocial support. But what happened [during an Ebola outbreak] was that we did not go back to the same people—like community health volunteers and other healthcare workers—who had prior knowledge and experience in handling Ebola in the area to come on board right away”.[Civil society representative]

Communication Challenges

“Thereare areas where their own network is extremely poor, the people cannot call even if the number is free of charge, it’s difficult for them to call because they don’t have network”.[MoH MH focal point]

“We weremeeting on Zoom in most cases, so if you do not have internet access, you will not be able to connect. It’s bad for us as a government entity, you would not be able to connect. And the partners are looking up to you as the government to call for a meeting, to arrange the meeting”.[MoH MH focal point]

Competing Priorities in Emergency Situations

“Thepopulation at one point in time no longer took the COVID-19 epidemic as a priority. When you compare it to other African countries or to Europe, people will say that they have many more problems than the COVID-19 epidemic. It wasn’t the priority, the population had other more pressing needs”.[Civil society representative]

“First of all, psychologically, people are suffering... It’s very important to help them. Because we are talking about washing hands, distance, but the suffering of people, they don’t address it, how to manage it”.[MoH MH focal point]

- The lack of political commitment and engagement

- Low prioritisation of mental health within emergency response structures

- The lack of available and sustainable funding

- The lack of monitoring, evaluation, and reporting mechanisms.

- Failure to apply lessons learned from previous emergencies.

- Human resources challenges (e.g., shortage in trained MHPSS staff, underpaid staff)

- Communication challenges (e.g., poor telecommunication infrastructure)

- Competing priorities in emergency situations.

3.2.2. Enablers and Opportunities in Improving MHPSS Components in Crisis Response

Capitalising on an Increased Political Will

“There werea lot of interventions in the media, involving political figures, religious leaders, doctors, nurses, at all levels to explain the disease to the population. It was really a surprise”.[WHO MH focal point]

“As the pandemicspread and people started exhibiting anxieties, depressions and fear, that had a toll on their productivity and function, their thinking changed and the approach changed for the better. So I believe that in planning for future pandemics or emergencies, we would not lose sight of the key component mental health has to play in such situations”.[WHO MH focal point]

“COVID-19 has helped us fast track is we are working actually, we’re finalising ournational suicide prevention strategy and programme, and that’s top of the agenda for the Minister of Health because there were reports of suicidal attempts at the quarantine sites”.[MoH focal point]

Promoting MHPSS Integration in Emergency Response

“Before, we didn’t have a section on MHPSS and emergencies in humanitarian setting, but nowwe’ve put that in our action plan so that we can plan, we can prepare for other disaster, not just COVID-19, and we can use what we’ve learned from COVID-19 response”.[MoH MH focal point]

Better Public Understanding of Mental Health following the Pandemic

“Peopleare really yearning for information [about mental health]… they really have been feeling uncertain. Then some are getting depressed and so on. So, we’re seeing people now appreciating that it’s possible for someone to feel that way no matter the results, so there’s a clear understanding of mental issues in communities”.[MoH MH focal point]

Integration of Mental Health in Routine Services and Strengthening Mental Health Systems in the Longer Term

“We are working on establishing a national tele-counselling and tele-psychiatric call centre at the national psychiatric referral hospital, … [This way] you don’t have to travel all the way to [the capital]”.[MoH MH focal point]

New Partnerships and Ways of Working

“We startedmapping now the mental health stakeholders, because we wanted to know what everyone is doing you know, UNHCR primarily based in the refugee camps and in with displaced populations, UNICEF is mainly children so we also involve the department of children services so that they can work together with UNICEF and the Ministry of Education, try to get people to like have different target groups because the pie is big, we’re trying to split it up and coordinate it better”.[MoH MH focal point]

“Our interaction during COVID, it was brilliant way of getting community engagement. … Our strategy over the years had been work with community actors so it becomes sustainable. They might even provide basic awareness raising, PFA in their local dialects”.[Civil society representative]

Drawing from Lessons Learned in Previous Outbreaks or Crises

“We canalso really give credit to the Ebola learning. So, lessons learned from Ebola set the pace for that, for the development of all those instruments, the referral pathway, documents developed. Everything we learn from Ebola, and integrated mental health”.[WHO MH focal point]

Sharing Experiences and Learning from Other Contexts

“Sharingexperiences from other countries is so important. For example, countries presenting what they have done, so that one country can draw on the experience of another country”.[MoH MH focal point]

“Something canbe developed either through tele-mentoring, a connection with other low and middle-income countries, particularly, you know, Africa region to share experiences with other professional policymakers, or clinicians to provide that kind of mentorship. (…) This could be a regional program allowing clinicians having issues in the facility to hook up to this system and get expert advice…”[Civil society representative]

- Capitalising on the increased attention to mental health during COVID-19

- Promoting MHPSS integration in emergency response

- Better public understanding of mental health following the pandemic

- Integration of mental health in routine services and strengthening mental health systems in the longer term

- Sustaining multi-stakeholder coordination of MHPSS activities beyond emergencies

- Engaging communities and people with lived experience is a key to improving the MHPSS services provided and addressing the stigma.

- Drawing from lessons learned in previous crises to inform the preparedness and response to future public health emergencies

- Building regional networks to facilitate sharing experiences and learning between countries in the region.

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations

- Establish an MHPSS response pillar as part of future responses to emergencies (guided by the IASC recommendations),

- Ensure that MHPSS components of national emergency preparedness and response plans include:

- -

- A feasible monitoring and evaluation framework

- -

- specific support for children and families

- -

- regular community engagement during the response

- -

- allocated resources to implement MHPSS components

- Stress test (through exercises and desktop scenarios) the MHPSS components of the national emergency response plans (particularly testing the capacity of human and financial resources) and refine plans accordingly

- Sensitize national leaders to the importance of MHPSS in emergency preparedness and response and lessons learned from COVID-19

- Undertake an in-depth review of MHPSS components of the national response to COVID-19 and identify lessons learnt

- Improve data and information systems in routine national mental health systems to improve this function during emergencies.

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UN Sustainable Development Group. UNSDG|Policy Brief: COVID-19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health. 2020. Available online: https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-covid-19-and-need-action-mental-health (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Santomauro, D.F.; Mantilla Herrera, A.M.; Shadid, J.; Zheng, P.; Ashbaugh, C.; Pigott, D.M.; Abbafati, C.; Adolph, C.; Amlag, J.O.; Aravkin, A.Y.; et al. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S0140673621021437/fulltext (accessed on 7 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health and COVID-19: Early Evidence of the Pandemic’s Impact: Scientific Brief, 2 March 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Sci_Brief-Mental_health-2022.1 (accessed on 7 March 2022).

- World Health Organization. The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Services: Results of a Rapid Assessment; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2020. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240036703 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- The Inter-Agency Standing Committe (IASC). Interim Briefing Note Adressing Mental Health and Psychosocial Aspects of COVID-19 Outbreak, IASC Reference Group on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novelcoronavirus-2019 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- African Union. Member States. Available online: https://au.int/en/member_states/countryprofiles2 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo. 2020. Available online: https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Mohammed, A.; Sheikh, T.L.; Poggensee, G.; Nguku, P.; Olayinka, A.; Ohuabunwo, C.; Eaton, J. Mental health in emergency response: Lessons from Ebola. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 955–957. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2215036615004514/fulltext (accessed on 21 July 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO Regional Office for Africa. The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Services: Results of a Rapid Assessment in the African Region; World Health Organization: Brazzaville, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2020; Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/publications/impact-covid-19-mental-neurological-and-substance-use-services-results-rapid (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Elsawy, W.; Fouad, H.; Saeed, K. Impact of COVID-19 on mental health and psychosocial support services in the Eastern Mediterranean Region-results of a rapid assessment. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2022, 28, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, F.J.; Dieleman, J.; Singh, L.; Whiteford, H.A. Donor Financing of Global Mental Health, 1995—2015: An Assessment of Trends, Channels, and Alignment with the Disease Burden. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169384. Available online: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0169384 (accessed on 21 July 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, J.; Kesner, C. Mental Health Funding and the SDGs What Now and Who Pays? 2016. Available online: https://odi.org/en/publications/mental-health-funding-and-the-sdgs-what-now-and-who-pays/ (accessed on 21 July 2022).

- Alkasaby, M.A.; Philip, S.; Agrawal, A.; Jakhar, J.; Ojeahere, M.I.; Ori, D.; Ransing, R.; Saeed, F.; Mohammadreza, S.; Shoib, S.; et al. Early career psychiatrists advocate reorientation not redeployment for COVID-19 care. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Building Back Better: Sustainable Mental Health Care after Emergencies; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; p. 104. [Google Scholar]

- Kola, L.; Kohrt, B.A.; Hanlon, C.; Naslund, J.A.; Sikander, S.; Balaji, M.; Benjet, C.; Cheung, E.Y.L.; Eaton, J.; Gonsalves, P.; et al. COVID-19 mental health impact and responses in low-income and middle-income countries: Reimagining global mental health. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 535–550. Available online: http://www.thelancet.com/article/S2215036621000250/fulltext (accessed on 6 June 2022). [CrossRef]

| Survey Response |

|---|

| Fully implemented |

| Almost fully implemented |

| Somewhat implemented |

| Not at all implemented |

| Do not know |

| Blank response |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Walker, A.; Alkasaby, M.A.; Baingana, F.; Bosu, W.K.; Abdulaziz, M.; Westerveld, R.; Kakunze, A.; Mwaisaka, R.; Saeed, K.; Keita, N.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in the COVID-19 Response in Africa: A Mixed-Methods Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159313

Walker A, Alkasaby MA, Baingana F, Bosu WK, Abdulaziz M, Westerveld R, Kakunze A, Mwaisaka R, Saeed K, Keita N, et al. Challenges and Opportunities for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in the COVID-19 Response in Africa: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):9313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159313

Chicago/Turabian StyleWalker, Alice, Muhammad Abdullatif Alkasaby, Florence Baingana, William K. Bosu, Mohammed Abdulaziz, Rosie Westerveld, Adelard Kakunze, Rosemary Mwaisaka, Khalid Saeed, Namoudou Keita, and et al. 2022. "Challenges and Opportunities for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in the COVID-19 Response in Africa: A Mixed-Methods Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 9313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159313

APA StyleWalker, A., Alkasaby, M. A., Baingana, F., Bosu, W. K., Abdulaziz, M., Westerveld, R., Kakunze, A., Mwaisaka, R., Saeed, K., Keita, N., Walker, I. F., & Eaton, J. (2022). Challenges and Opportunities for Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in the COVID-19 Response in Africa: A Mixed-Methods Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 9313. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19159313