Abstract

Regular physical activity (PA) engagement has multiple benefits for individual general health at all ages and life stages. The present work focuses on badminton, which is one of the most popular sports worldwide. The aim was to conduct a systematic review focused on examining and analysing this sport and the benefits it brings to the health of those who engage in it. Examination was conducted from the viewpoint of overall health and provides an overview of the current state-of-the-art as presented in published scientific literature. PRISMA 2020 guidelines were adhered to. An exhaustive search was conducted of four electronic databases or search engines: Web of Science, Scopus, MEDLINE and Google Scholar. The search terms used were “badminton AND health” and “badminton AND benefits”. In total, 27 studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review. After analysing the results, it was concluded that badminton engagement may lead to an improvement in all areas, the most studied being those related to physical health, in particular the improvement of cardiac and pulmonary functions and the development of basic physical capacities.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) establishes that health is the “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” [1]. This is currently considered to be framed by a set of determinants that include personal, biological, social, behavioural, economic, cultural and environmental factors which determine the state of health of individuals [2,3].

According to the WHO [1] definition, three types of health are established to make up comprehensive health:

Firstly, physical health refers to wellbeing of the body and optimal functioning of the organism. Secondly, mental health is considered as the absence of mental disorders or disabilities. It is a state of well-being in which individuals start to realise their capabilities and cope with the stresses of day-to-day life, work productively and contribute to their community. Thirdly, social health includes adaptation and self-management as skills used to face up to environmental changes and challenges, alongside the ability to establish satisfactory relationships with other people.

Regular physical activity (PA) engagement has been associated with important physical, mental, social and affective-emotional benefits. Specifically, the WHO [4] indicates that PA contributes to the prevention of non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes; reduces symptoms of depression and anxiety; improves reasoning, learning and judgement skills; ensures the healthy growth and development of young people and improves general well-being. Indeed, up to 5 million deaths a year could be avoided through greater PA engagement [4].

Physical inactivity is one of the most important risk factors for mortality (20–30% higher risk of death). According to WHO data (2019), one in four adults do not meet recommended PA levels. Issues around inactivity are currently heightened due to the pandemic (COVID-19) being experienced worldwide [5]. A study carried out by Wilke et al. [5] in a total of 14 countries showed that PA levels decreased during the pandemic.

The negative effects of inactivity have been widely studied, indicating poorer outcomes in academic performance [6]; mental health, such as higher levels of stress and anxiety [7,8,9,10,11]; physical health, associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease [12,13]; reduced motor skill development [14,15] and lost opportunities to improve social relationships [16], among others.

Considering that participation in physical activity in general exerts benefits on well-being, health and social satisfaction [17], the present work sought to focus explicitly on badminton engagement and its impact on health. According to the International Federation of Sport for All [18] and the Madison Beach Volley Tour [19], it is also one of the most popular sports in the world, being widely practised worldwide, namely by more than 200 million individuals [20], since its inclusion in the 1992 Olympic Games [21]. This sport is characterised by high-intensity intermittent activity and has five events (men’s and women’s singles, men’s and women’s doubles, and mixed doubles), for which specific preparation is required in terms of technique, psychological control and physical fitness [21,22].

Scientific production in the field of badminton is scarce and diverse, focusing on the thematic areas of health and training [23,24] Although the number of publications has increased significantly since 2007, with Asian and European countries showing the highest rate of productivity [23,24], it is still low, particularly in terms of the benefits that this sport brings to the overall health of the athlete or player.

Despite the scarcity of studies, badminton, like other sports, has a number of health benefits. Recent studies provide significant effects of this sport on physical health, such as physiological improvements (increased power and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and decreased blood pressure and resting heart rate) [25], the improvement of basic physical qualities [26] and improving the mental and social health of individuals [27,28].

For this reason, the present work is of great importance to the scientific community that has already extensively studied the most frequent injuries sustained in badminton, according to the competitive level of badminton practice, but never its benefits [29,30].

Thus, the present article reports a systematic review focused on the examination and analysis of the sport of badminton and the benefits it brings to the health of those who play it from the viewpoint of comprehensive health (physical, mental and social). Furthermore, analysis will be conducted as a function of age and sex. The aim of this is to provide an overview of the current state of the art.

2. Materials and Methods

The review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guidelines laid out in “The PRISMA 2020: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews” [31].

2.1. Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted of three electronic databases (Web of Science, Scopus and MEDLINE) between December 2020 and March 2021. A further update was then conducted in January 2022.

Given the scarcity of publications in this field, a number of databases were considered, and the search was not limited by the year of publication. Firstly, a more general search was carried out concering just “badminton” which produced many results (1693 in Scopus and 1581 in WoS), and a lot of information that did not fit the objective of our study: the benefits of practicing badminton. For this, we decided to refine the search to even more specific terms, such as mental health, but with a very low number of results; therefore, we decided to opt for the two expressions “health” and “benefits”, which were the ones that provided us with studies related to our objective, as other research has carried out with different sports, specifically regarding tennis [32].

Then, the final search terms used were “badminton AND health” and “badminton AND benefits”, also using the Boolean operator “and”.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were eligible that (1) were scientific articles without exclusion of any type of research design; (2) were published in the English or Spanish language and had been peer reviewed; (3) examined badminton engagement with a view to attaining some type of comprehensive health benefit (cognitive, mental, physical, fitness, motor and social and emotional), regardless of age or the type of badminton engaged in.

In order to appropriately apply the presented inclusion criteria, the title of each identified paper and its abstract was first read. This was followed by a reading of the full text. Papers that did not examine the benefits of badminton were discarded.

The exclusion criteria applied were: (1) non-scientific articles, (2) articles published in languages other than English or Spanish, (3) articles not subject to peer reviewed and (4) articles that did not provide conclusions on the benefits of badminton practice in any of the areas of integral health.

2.3. Data Selection

All search results were exported to the Zotero library and duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts of retrieved papers were screened by one reviewer, using the inclusion criteria described above and, subsequently, verified by another independent reviewer. If a study was mentioned several times, only the most recent publication was included in analysis. Reference lists of included studies, as well as related systematic reviews, were examined to identify any additional studies. The full texts of remaining papers were then reviewed to make a final decision on inclusion. Disagreements on the inclusion of studies were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. Of the three experts, two were Masters in Sports Science and international badminton players and the third was a Ph.D. professor and badminton expert who is the Chair of the Sports Science and Medical Research Commission of the Badminton World Federation.

2.4. Data Extraction

Categorisation and analysis were performed using ATLAS.ti software (version 9). Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked for accuracy by another. The following characteristics were extracted and recorded for each included study:

Table 1: (1) papers; (2) authors; (3) year; (4) country in which study was conducted; (5) type of activity; (6) sample; (7) population and age; (8) intervention duration. Item (5), type of activity, referred to the type of badminton engaged in by participants and could include recreational, academic (referring to badminton played in an educational environment) and professional. Item (7) refers to the age of participants, which was classified, according to WHO criteria laid out on the Euroinnova website [33], as infancy (0–6 years), childhood (6–12 years), adolescence (12–20 years), youth (20–25 years), adulthood (25–60 years) and old age (60 upwards).

Table 1.

Main data gathered from selected studies.

Table 2: (1) study design; (2) aim; (3) type of intervention program; (4) variables; (5) instruments; (6) health benefits of badminton.

Table 2.

Main data collected from analysed studies.

Item (6), health benefits of badminton, referred to overall health, as stated in Section 2.2 of the inclusion criteria.

Study quality was analysed using descriptive statistics (absolute frequencies).

2.5. Assessment of Study Methodological Quality

The risk of bias in each eligible paper was assessed via a dichotomous nominal scale (yes/no), which was developed to assess sample adequacy in the 27 studies. Criteria used for continuous variables are listed in Section 2.2 (inclusion criteria). Inter-rater agreement pertaining to the classification of data gathered from included papers was 93%.

3. Results

3.1. Database Searches

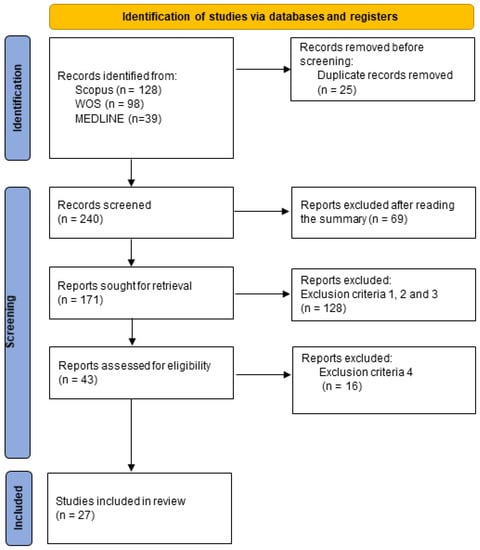

The PRISMA flowchart in Figure 1 illustrates the identification, selection, eligibility and inclusion of studies in the systematic review. The database search yielded 328 papers. In total, 27 studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review.

Figure 1.

Research paper selection flowchart.

3.2. Description of Included Studies

3.3. Findings Pertaining to the Characteristics of Selected Studies

With regards to the publication date of examined studies, an increase in the production of the literature on the subject can be seen in recent years, with 2020 being the most productive year, producing 25% of studies (n = 6), followed by 2019 (n = 4; 22.2%) and 2017 (n = 4; 14.8%). In terms of the countries in which studies were conducted, most studies were conducted in China and the United States (n = 4 in each country), followed by the United Kingdom, Turkey and Taiwan (n = 3 in each case).

In relation to the type of badminton considered by included studies, twelve papers were found on recreational badminton, eleven papers on academic badminton and four papers analysing professional badminton.

The total sample covered by the 27 included papers pertained to 20,983 participants. In terms of the sex of participants, 23 studies provide this information, corresponding to a total sample of 12,153 participants. Of these, 6308 men (51.9%) and 5845 (48.1%) women were considered.

When classifying papers according to population and age (Table 3), it was found that the population with which most studies were carried out pertained to adolescents (n = 11), with the least often examined population being children (n = 4).

Table 3.

Populations examined by included studies.

The samples corresponding to the articles analysed refer to convenience samples in most cases (n = 22), either because they are expressly stated or because it is deduced after analysis of the text. Other articles used random samples (n = 4) and snowball sampling (n = 1).

Of the 27 papers analysed, the predominant study design used was experimental (n = 14). Of these, n = 8 were found to have used a control group, whilst n = 6 did not include a control group. Intervention durations ranged from less than 1 month (n = 3), 1 to 3 months (n = 6) and more than 3 months (n = 5).

The articles that carried out a badminton intervention programme (n = 15) had a variety of purposes, most of them related to the measurement of physiological parameters and fitness level or physical qualities (n = 12) and others to mental health (n = 3).

Examined variables were also diverse, with studies typically analysing more than one variable. The most commonly analysed variable was physical health (n = 17), followed by mental health (n = 10) and social health (n = 8) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Types of health examined.

With regards to data collection instruments, most studies used questionnaires (n = 13), with different physical condition tests (n = 6) and heart rate (n = 5) also standing out as being used to provide measures.

Finally, in terms of the results obtained, n = 15 articles reported significant positive improvements in several variables related to different types of health. Six articles found no significant differences in any of the study variables. No studies with negative significance were found.

4. Discussion

Through the practice of badminton, we can tackle physical inactivity, a worldwide problem that affects one in four people according to the WHO and, in turn, bring benefits to our overall health [4].

4.1. Physical Health Benefits

In consideration of physical health (improvement in physical and physiological parameters, physical and motor fitness and the absence of disease), three studies demonstrated benefits of badminton on cardiac function [25,45,49]. A study by Patterson et al. [43], examined adult women following eight weeks of badminton and showed a decrease in heart rate (HR) both at rest and during submaximal running. This finding was reiterated by research conducted by Chen et al. [28] and Ya and Li [49] with young men and women. These studies indicated that badminton was beneficial for cardiac function.

Several studies showing the benefits of badminton on respiratory capacity were also uncovered. In this sense, Patterson et al. [45] and Deka et al. [46] showed that badminton produced an increase in aerobic fitness and capacity (VO2max) in adults. Ya and Li [49] found the benefits of badminton on lung function in young men and women, whilst Dogruel et al. [43], in a study of children and adolescents of both sexes with asthma, showed that badminton decreased asthma symptoms and increased forced expiratory volume.

One study has also been conducted which demonstrates other benefits at a physical level. This study indicated a strengthening of the lens ligaments and normalisation of the ciliary muscle tone in boys and girls with different optical refractions following a one-year badminton engagement [40], whilst fewer postural asymmetries were found in adolescent boys playing badminton relative to adolescents not playing any sport [36]. Further outcomes included higher high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, associated with a reduced likelihood of coronary heart disease, in adults and elderly men and women [39]; improved body shape in adolescent females due to the effect of badminton on development in the specific limb dimensions engaged during play [26] and better functional physical fitness and self-perceived functional health in the elderly, regardless of sex, alongside retarded biological degradation [54]. Higher bone mineral density in the femoral neck, humerus, lumbar spine and legs of male badminton players was also seen relative to those who played ice hockey or did not participate in any organised training activity [55]. Finally, Schnohr et al. [42], in a study carried out in young, adult and elderly people of both sexes, compared the life expectancy effects of engagement in various sports. These authors concluded that, relative to sedentary individuals, badminton players had a 6.2-year higher life expectancy, with this being the sport associated with the second greatest life expectancy benefit (tennis 9.7 years, badminton 6.2 years, football 4.7 years, cycling 3.7 years, swimming 3.4 years, etc.).

With regards to the benefits of badminton in terms of improving physical fitness, five studies reported benefits in adolescents of both sexes, such as improved muscular strength and endurance, explosive strength, power, flexibility, and cardiorespiratory fitness [26,34,35,73], obtaining significant improvements in all of the aforementioned parameters, with the only exception being body composition [35].

Yan and Li [49] also showed that badminton engagement in young people led to improved speed in both men and women, with better flexibility also emerging within women. In adults, Patterson et al. [45] showed improvements in vertical jump performance.

With regards to benefits at the motor level, Duncan et al. [37] conducted a study with children of both sexes and mainly focused on motor skills. They showed that both the quality and execution of motor skills improved following a BWF shuttle time structured program, with the most significant changes being obtained in younger children (6–7 years) rather than in older children (10–11 years). In addition, a significant gender difference was observed, with boys scoring significantly higher than girls on movement quality scores, regardless of age. Few studies were uncovered in young people and adolescents. In contrast, improvements in muscle coordination [50] and manipulative skills have been found in the elderly [54].

4.2. Mental Health Benefits

The present review identified badminton engagement to reduce depressive symptoms in young people with intellectual disabilities [25]. In adolescents, Zhao et al. [51] showed a decrease in depression and anxiety and improved self-esteem after 20 weeks of aerobic badminton exercise. In adult male and female patients with mental illness, Ng et al. [28] found that those who played badminton had greater overall motivation, one month after discharge, and improved psychological wellbeing [18].

At the cognitive level, five papers reporting benefits of badminton were uncovered. Takahashi and Grove [41] compared the effects of badminton on inhibitory function (the ability to control attention, behaviour, thoughts and/or emotions in order to overcome a strong internal bias or external attraction and instead do what is most appropriate or necessary). In Diamond [74], with results produced using simple running or sitting rest, as control conditions in young men and women, badminton significantly improved performance over sitting rest, whereas running did not. Similarly, a study conducted by Liao et al. [48] with male and female youth and adults, compared the effect of expertise on action inhibition in badminton players and non-athletes. Employing the stop-signal paradigm developed by Logan [68], this study found that badminton players were more likely to successfully inhibit their responses during stop trials than individuals who did not play sport, with response inhibition performance improving in line with the competitive level of badminton players. This underlines the relationship between cognitive ability and sport performance in badminton players.

Hung et al. [44] compared an open-skill exercise (badminton) with a closed-skill exercise (running) in young males, finding that badminton engagement resulted in higher levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factors and better task-switching performance, consequently improving executive function. In male adolescents and young adults, Dube et al. [50] demonstrated that badminton engagement resulted in a shorter visual reaction time compared to those who do not engage in any sporting activity, subsequently improving cognitive functions, alertness and concentration.

A study by Akin et al. [47] in children and adolescents of both sexes with autism spectrum disorder found that a 10-week badminton program improved attention.

4.3. Social Health Benefits

With regards to social benefits, Patterson et al. [45] found increased motivation to spend time with friends and establish new relationships amongst women. Through interviews with adults and elderly men and women, Chan and Lee [27] indicated that badminton was a conduit for self-expression and mood regulation, supporting personal development and social engagement [18]. Badminton also increased intrinsic motivation to perform tasks, the desire to compete (as a major benefit of participation) and general wellbeing [38]. In adolescents, badminton has been shown to increase motivation towards PA engagement [52].

The findings of the present review pertaining to the benefits of badminton engagement should be interpreted with caution and considered in light of the following limitations. Firstly, the high level of heterogeneity detected in the included studies (age, stage, study design, type of badminton played) limits the robustness of outcomes and reduces their generalisability. Secondly, due to the scarcity of studies conducted in this line of research, it is advisable to broaden the search to include papers published in more languages (such as Chinese, Korean, Japanese and French). This would be useful given that badminton is one of the most popular sports worldwide and it is highly likely that more research has been conducted in Asian countries. Finally, the disparity of the variables and instruments used to assess health improvement makes it difficult to compare the findings produced.

Although the study focuses exclusively on the benefits of practising badminton, without assessing other more negative or harmful aspects that the practice of any other sport always entails, such as the risk of injuries. However, the scientific literature already indicates that in the practice of amateur or recreational badminton, injuries are neither more numerous nor more important than those caused by the practice of any other sport or physical activity at these levels [29,30].

As a limitation of the study, the type of health and the variables within each of them, analysis is very diverse, with physical health being the most covered topic in the articles. A greater number of studies are needed in each of the areas of health described in this work, especially in mental and social health, in order to reach more reliable conclusions about the benefits of this sport.

5. Conclusions

As a general conclusion, it can be stated that the studies analysed demonstrate that badminton engagement can lead to all types of benefits associated with overall health improvement. Moreover, impact has been shown in all types of populations, ages and sexes. Furthermore, badminton, compared with other types of physical sporting activities, offers, for the most part, better outcomes pertaining to the three types of health (physical, mental and social), with benefits also seen for disabled individuals and even in visual health.

Conclusions pertaining to the specific benefits are presented in Table 5 for ease of understanding.

Table 5.

Benefits produced by badminton engagement in different populations and sexes.

In conclusion, the present work provides coaches, monitors, practitioners, athletes and Physical Education teachers with specific guidance for carrying out badminton sports programs adapted to different populations and sexes with the aim of developing aspects of comprehensive health.

Despite the fact that in recent years there has been an increase in research on the sport of badminton, there is still a lack of studies on the health benefits it generates, so it is necessary to investigate in all areas but especially, given its current relevance, in mental and emotional health.

As future lines of research, following this review, we consider it of interest to focus research on the comparative analysis of the health effects between badminton and other types of sports and to reinforce studies on children and the elderly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.L., D.C.-M. and R.P.-R.; methodology, R.P.-R. and D.C.-M.; formal analysis, J.A.L. and E.P.-G.; investigation, J.A.L., E.P.-G., R.P.-R. and D.C.-M.; data curation, D.C.-M., E.P.-G. and J.A.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.L., D.C.-M. and E.P.-G.; writing—review and editing, R.P.-R.; visualization, J.A.L. and R.P.-R.; supervision, D.C.-M., E.P.-G. and R.P.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European project. “Badminton for All” (590603-EPP-1-2017-1-ES-SPO-SCP) of the Erasmus + programme.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Basic Documents, 45th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43134 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- De La Guardia, M.A.; Ruvalcaba, J.C. La salud y sus determinantes, promoción de la salud y educación sanitaria. J. Negat. No Posit. Results 2020, 5, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casazola, J. La salud y sus determinantes: Crisis socioambiental y relaciones sociales de discriminación. Pacha Derecho Y Vis. 2021, 2, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Physical Activity 2018–2030: More Active People for a Healthier World. World Health Organization. 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327897 (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Wilke, J.; Mohr, L.; Tenforde, A.S.; Edouard, P.; Fossati, C.; González-Gross, M.; Sánchez Ramírez, C.; Laiño, F.; Tan, B.; Pillay, J.D.; et al. A Pandemic within the Pandemic? Physical Activity Levels Substantially Decreased in Countries Affected by COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Zeng, N.; Ye, S. Associations of Sedentary Behavior with Physical Fitness and Academic Performance among Chinese Students Aged 8–19 Years. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ströhle, A. Physical activity, exercise, depression and anxiety disorders. J. Neural. Transm. 2009, 116, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, T.; Broocks, A. Therapeutic impact of exercise on psychiatric diseases. Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Sports Med. 2000, 30, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, M.W.; Church, T.S.; Craft, L.L.; Greer, T.L.; Smits, J.A.; Trivedi, M.H. Exercise for mood and anxiety disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007, 9, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segar, M.; Jayaratne, T.; Hankon, J.; Richardson, C.R. Fitting fitness into women’s lives: Effects of a gender-tailored physical activity intervention. Womens Health 2002, 12, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werneck, A.O.; Silva, D.R.; Malta, D.C.; Souza-Júnior, P.R.B.; Azevedo, L.O.; Barros, M.B.A.; Szwarcwald, C.L. Physical inactivity and elevated TV-viewing reported changes during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with mental health: A survey with 43,995 Brazilian adults. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 140, 110292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-M.; Shiroma, E.J.; Lobelo, F.; Puska, P.; Blair, S.N.; Katzmarzyk, P.T. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: An analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 2012, 380, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.C.; Pate, R.R.; Lavie, C.J.; Sui, X.; Church, T.S.; Blair, S.N. Leisure-time running reduces all-cause and cardiovascular mortality risk. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 472–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.A.; Riethmuller, A.; Hesketh, K.; Trezise, J.; Batterham, M.; Okely, A.D. Promoting fundamental movement skill development and physical activity in early childhood settings: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2011, 23, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellows, L.L.; Davies, P.L.; Anderson, J.; Kennedy, C. Effectiveness of a physical activity intervention for Head Start preschoolers: A randomized intervention study. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2013, 67, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonell, T.; Antoñanzas, J.L.; Lope Álvarez, Á. La educación física y las relaciones sociales en educación primaria. IJODAEP 2018, 2, 269–282. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6432668&orden=0&info=link (accessed on 15 December 2020). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lassandro, G.; Trisciuzzi, R.; Palladino, V.; Carriero, F.; Giannico, O.V.; Tafuri, S.; Valente, R.; Gianfelici, A.; Accettura, D.; Giordano, P. Psychophysical health and perception of well-being between master badminton athletes and the adult Italian population. Acta Biomed. 2021, 92, e2021253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, M. El bádminton de competición: Una revisión actual. EFDeportes 2010, 149. Available online: http://www.efdeportes.com (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Madison Beach Volley Tour. 10 Deportes más Practicados en el Mundo. Available online: https://beachvolleytour.es/10-deportes-mas-practicados-en-el-mundo (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Kwan, M.; Cheng, C.L.; Tang, W.T.; Rasmussen, J. Measurement of badminton racket deflection during a stroke. Sports Eng. 2010, 12, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phomsoupha, M.; Laffaye, G. The science of badminton: Game characteristics Anthropometry, Physiology, Visual Fitness and Biomechanics. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello-Manrique, D.; González-Badillo, J.J. Analysis of the characteristics of competitive badminton. Br. J. Sports Med. 2003, 37, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanca-Torres, J.C.; Ortega, E.; Nikolaidis, P.T.; Torres-Luque, G. Bibliometric analysis of scientific production in badminton. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2020, 15, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, L.M.; Sasai Morimoto, L.M.; Ribas da Silva, S.; Cabello-Manrique, D. A scientometric study about badminton applied to sports science research. In Science and Racket Sports VI; Kondrič, M., Cabello, D., Pinthong, M., Eds.; Mahidol University: Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, 2019; pp. 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-C.; Ryuh, Y.-J.; Donald, M.; Rayner, M. The impact of badminton lessons on health and wellness of young adults with intellectual disabilities: A pilot study. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 2021, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovba, I.R.; Stolyarova, N.V.; Petrozak, O.L.; Ishmatova, A.R. Benefits of badminton driven academic physical education model for female students. Teor. Prak. Fiz. Kult. 2019, 2019, 54–56. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85071149003&partnerID=40&md5=9682b01f06de672a22cbe4c2d463fe6f (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Chan, B.C.L.; Lee, B. Wellbeing and personality through sports: A qualitative study of older badminton players in two cultures. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2020, 12, 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.S.W.; Leung, T.K.S.; Ng, P.P.K.; Ng, R.K.H.; Wong, A.T.Y. Activity participation and perceived health status in patients with severe mental illness: A prospective study. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2020, 30, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gijon-Nogueron, G.; Ortega-Avila, A.B.; Kaldau, N.C.; Fahlstrom, M.; Felder, H.; Kerr, S.; King, M.; McCaig, S.; Marchena-Rodriguez, A.; Cabello-Manrique, D. Data Collection Procedures and Injury Definitions in Badminton: A Consensus Statement According to the Delphi Approach. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2022, 10.1097/JSM.0000000000001048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchena-Rodriguez, A.; Gijon-Nogueron, G.; Cabello-Manrique, D.; Ortega-Avila, A.B. Incidence of injuries among amateur badminton players: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2020, 99, e19785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 35, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pluim, B.M.; Staal, J.B.; Marks, B.L.; Miller, S.; Miley, D. Health benefits of tennis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Euroinnova. Clasificación de las Etapas de la Vida por Edad. Available online: https://www.euroinova.edu.es/blog/etapas-de-la-vida-por-edad (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Lee, E.-J.; So, W.-Y.; Youn, H.-S.; Kim, J. Effects of School-Based Physical Activity Programs on Health-Related Physical Fitness of Korean Adolescents: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 18, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.H.H. The effect of three sport games in physical education on the health-related fitness of male university students. Eur. Phy. Educ. Rev. 2020, 24, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, H.T.; Arslan, F. The examination of postural variables in adolescents who are athletes and non-athletes. Int. J. Appl. Exerc. Physiol. 2020, 9, 140–147. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2426494395/abstract/6E930F6CCB1F470APQ/1?accountid=14542 (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Duncan, M.J.; Noon, M.; Lawson, C.; Hurst, J.; Eyre, E. The Effectiveness of a Primary School Based Badminton Intervention on Children’s Fundamental Movement Skills. Sports 2020, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzzelli, A.A.; Draper, J.A. Examining the motivation and perceived benefits of pickleball participation in older adults. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2020, 28, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassef, Y.; Lee, K.J.; Nfor, O.N.; Tantoh, D.M.; Chou, M.C.; Liaw, Y.P. The Impact of Aerobic Exercise and Badminton on HDL Cholesterol Levels in Adult Taiwanese. Nutrients 2019, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarutta, E.; Tarasova, N.; Markossian, G.; Khodzhabekyan, N.; Harutyunyan, S.; Georgiev, S. The state and dynamics of the wavefront of the eye in children with different refractions engaged in regular sport activities (badminton). Russ. Ophthalmol. J. 2019, 12, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Grove, P.M. Comparison of the effects of running and badminton on executive function: A within-subjects design. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnohr, P.; O’Keefe, J.H.; Holtermann, A.; Lavie, C.J.; Lange, P.; Jensen, G.B.; Marott, J.L. Various leisure-time physical activities associated with widely divergent life expectancies: The copenhagen city heart study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1775–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogruel, D.; Altintas, D.U.; Yilmaz, M. Effects of physical exercise on clinical and functional parameters in children with asthma. Cukurova Med. J. 2018, 43, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.; Tseng, J.; Chao, H.; Hung, T.; Wang, H. Effect of acute exercise mode on serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and task switching performance. J. Clin. Med. Res. 2018, 7, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, S.; Pattison, J.; Legg, H.; Gibson, A.M.; Brown, N. The impact of badminton on health markers in untrained females. J. Sports Sci. 2017, 35, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, P.; Berg, K.; Harder, J.; Batelan, H.; McGrath, M. Oxygen cost and physiological responses of recreational badminton match play. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2017, 57, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akin, S.; Kilinç, F.; Söyleyici, Z.; Göçmen, N. Investigation of the effects of badminton exercises on attention development in autistic children. Eur. J. Phys. Educ. Sport Sci. 2017, 3, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Meng, F.; Chen, Y. The relationship between action inhibition and athletic performance in elite badminton players and non-athletes. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2017, 12, 574–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Li, Y. The influence of different sports on college students’ physical health. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Management Science and Innovative Education (Msie 2015), Xi’an, China, 12–13 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, S.P.; Mungal, S.U.; Kulkarni, M.B. Simple visual reaction time in badminton players: A comparative study. Natl J Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 5, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, K.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Li, J. Physical education affecting on cognition and emotion: Moderate badminton training improve self-esteem, depression, and spatial memory in non-athlete junior college female students. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 57, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanelli, M.L. Badminton, a sport with a potential to increase the adherence of adolescents to the physical education programme in secondary school good practices in health promotion and innovative strategies. Pensar Prática 2014, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Heo, J.; Kim, J. The benefits of in-group contact through physical activity involvement for health and well-being among Korean immigrants. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2014, 9, 23517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, M.H.S.; Cheung, S.Y.; Chow, B.C. The effects of tai-chi-soft-ball training on physical functional health of chinese older adult. J. Hum. Sport Exerc. 2011, 6, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tervo, T.; Nordstrom, P.; Nordstrom, A. Effects of badminton and ice hockey on bone mass in young males: A 12-year follow-up. Bone 2010, 47, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zung, W.W.K. A self-rating depression scale. Arch. Psychiatry 1965, 12, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Overall, L.E.; Gorham, D.R. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1969, 10, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-15: Validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom. Med. 2002, 64, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buysse, D.J.; Reynolds, C.F.; Monk, T.H.; Berman, S.R.; Kupfer, D.J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989, 28, 193–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.S.; Lo, A.W.; Leung, T.K.; Chan, F.S.; Wong, A.T.; Lam, R.W.; Tsang, D.K.Y. Translation and validatio n of the Chinese version of the short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale for patients with mental illness in Hong Kong. East Asian Arch. Psychiatry 2014, 24, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Caro, F.G.; Burr, J.A.; Caspi, E.; Mutchler, J.E. Motives That Bridge Diverse Activities of Older People. Act. Adapt. Aging 2010, 34, 115–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, D.A. Test of Gross Motor Development-2; Prod-Ed: Austin, TX, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Juniper, E.F. Pediatric Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire. Qual. Life Res. 1996, 5, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.L.; Huang, C.J.; Tsai, Y.J.; Chang, Y.K.; Hung, T.M. Neuroelectric and behavioral effects of acute exercise on task switching in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markland, D.; Ingledew, D.K. The measurament of exercise motives: Factorial validity and invariance across gender of a revised Exercise Motivations Inventory. Br. J. Health Psychol. 1997, 2, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, G.A. Psychophysical bases of perceived exertion. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1982, 14, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, G.D. On the ability to inhibit thought and action: A users’ guide to the stop signal paradigm. In Inhibitory Processes in Attention, Memory, and Language; Dagenbach, D., Carr, T.H., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 189–239. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T. The development of depression: A cognitive model. In The Psychology of Depression: Contemporary Theory and Research; Friedman, R.J., Katz, M.M., Eds.; Winston & Sons: Washington, DC, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.E. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Test Manual); Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. Society and the Adolescent Self-Image; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Fillenbaum, G.G. Multidimensional Functional Assessment of Older Adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services Procedures; Lawrence Erlbaum Association: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Fernández, J.; de la Aleja Tellez, J.G.; Moya-Ramón, M.; Cabello-Manrique, D.; Méndez-Villanueva, A. Gender differences in game responses during badminton match play. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2013, 27, 2396–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2013, 64, 135–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).