1. Introduction

When working with diversity and diversity management our focus is usually on the conscious factors (factors within our awareness) which drive our observed behaviour. Much research has been done on the conscious manifestations of diversity in organisations and how diversity management can be implemented to ensure to increase the benefits and reduce the disadvantages of diversity for all stakeholders in and of organisations [

1]. However, by focussing on the influence of unconscious factors (factors outside of our awareness) on diversity will assist in forming a more holistic understanding of observed human behaviour in the context of diversity and diversity management [

1,

2,

3]. Several research projects have focused on the experiences of diversity in group relations conference from the perspective of the researchers, consultancy staff, the directors and participants of such conferences [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Ref. [

8] explored the experiences of the directors of a group relations conference (RIDE), whereas [

6] explored the person-in-role implications for the director of a group relations conference exploring diversity. Research about the dynamics in group relations conferences exploring diversity include, but not limited to, the Nazareth Group Relations conferences, which were held on six occasions, initially focused on Germans and Jews and later included Palestinians and others [

4,

5]. The research about this conference reported on the unconscious dynamics evident when studying hatred and the historical roles of Germans and Jews in the Holocaust. The conference, entitled Authority, Leadership and Peacemaking, emphasized the role of Jewish, Palestinian and other Arab Diaspora communities in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict [

7]. Although this research about RIDE differed from the aforementioned research, viz. RIDE was held consecutively from 2000 to 2003 and 2005 to 2015, and focused on diversity dynamics primarily in South African organisations and society. The middle-term nature of RIDE allowed me to reflect on diversity dynamics spanning over a 13-year period.

The Robben Island diversity experiences (RIDE) is a group relations training event using Tavistockian Technology (also known as the Group Relations training model) to study the underlying, unconscious, and covert South African diversity dynamics as they manifest among managers and officials in the fields of change, diversity management, transformation, and human resources management. These diversity dynamics evident in RIDE may also be viewed as a microcosm of South African diversity dynamics since 2000. The Robben Island Diversity Experience has contributed to the understanding about individual and group diversity dynamics. Diversity dynamics is defined as a relational phenomenon through which individuals, across differences and similarities, make certain assumptions about others. The individuals then behave, on both a conscious and an unconscious level, in a particular way towards each other, based on these assumed differences and similarities [

1,

8,

9].

This article is an exploration of my reflections about diversity dynamics. My aim is to describe the experiences of a few hundred people participating in the Robben Island Diversity Experience (known as RIDE) from 2000 to 2013 (with RIDE not taking place in 2004), using analytic autoethnography to analyse and interpret the conscious and unconscious diversity dynamics operating among these participants.

In sharing with you my reflections about the diversity dynamics operating in RIDE, I start by explaining the significance of Robben Island as a container for South African diversity.

3. Research Methodology

Qualitative and descriptive research [

31] was chosen to allow for in-depth exploration of diversity dynamics in a specific experiential diversity experience [

32]. Hermeneutic phenomenology [

33] was chosen as research paradigm, which allowed for the in-depth understanding of the participants’ experiences around diversity. The paradigm also enabled us to interpret the data from the systems psychodynamic stance in an attempt to develop knowledge around the conscious and unconscious manifestation of diversity dynamics, see [

33]. The research strategy used was analytic auto-ethnography, an approach to research and writing that seeks to describe and systematically analyse (graphy) personal experience (auto) to understand cultural experience (ethno) [

34].

Following [

35], I collected data from my personal experiences as a consultant and director during RIDE from 2000 to 2013, with RIDE not taking place in 2004. In my role as director of several of the RIDE conferences, I kept process notes of my experiences during the different session. These process notes were used during the conference to make sense of the here and now, as well as there and then dynamics that occurred during the conference. After the conference these notes, my reflections and experiences were used as data in this study. I also used data from existing research (masters’ dissertations, articles, chapter, and conference presentations). From these different sources of data, I extricated particular vignettes relevant to the aim of this study. I used thematic analysis [

33,

36], from which themes emerged. I then used double hermeneutics [

37] to interpret the data from the systems psychodynamic consultancy stance. The findings were integrated with relevant literature and different working hypotheses were generated [

16]. Ethics clearance, 2015_CRERC_023(SD), was obtained for the research from the University of South Africa.

3.1. Findings

I have introduced RIDE to you as a container in which staff and members could study diversity dynamics. Now I would like to share with you my reflections and those of some of the staff members about the diversity dynamics that occurred in the RIDE society over 13 years, and consequently also in South African society. The two main themes are the diversity dynamics evident in earlier RIDE’s and diversity dynamics evident in recent RIDE’s.

3.2. Diversity Dynamics Evident in Earlier RIDEs

After the 2000 event, the members were asked about their experiences of RIDE. The following overview is based on these data obtained from members, and articles by [

1,

3,

8], and my own reflections.

3.3. Race Used as a Container for Unresolved Diversity Matters

During first few RIDEs the RIDE citizens predominantly focused on the primary dimensions of diversity, with priority given to race and gender. As a participant stated: “It was as if this colour thing was still important for people to survive in the new South Africa”. This could be an indication of the extent to which the South African society fixated on race.

The struggle for power and position were evident in the early RIDE society—with power and status primarily allocated according to subgroup membership, especially with regard to race and gender.

The black male. The black men seemed to be empowered in the RIDE society. The older black men, who seemed to represent the struggle of the past, were very prominent at the beginning of the experience and became more silent as time went on in the early RIDEs. They appeared to contain the new stability in the country and “being there” may have been enough. The younger black men appeared to be very active and acted powerfully and assertively, with quite a lot of competition between them [

1], p. 56.

The black female. The older woman represented a mother figure to the group, i.e., the younger black people see her as a role model who looked after them during difficult times. The younger women were more silent than the younger black men but were very empowered. One black young woman expressed her need to take all opportunities, and for whites to get out of her way [

1], p. 56.

The coloured male. The older men seemed to be empowered and were apparently networking with everybody about working together in future. This could have enabled them not to take up the ascribed role projected onto them with regard to their racial representation. A coloured man stated:

“I don’t represent all the coloureds, but they expected me to carry this on behalf of all coloureds. The same happened with the Indians” [

1], p. 56.

The coloured female. It appeared that coloured women had quite a difficult time relating to their racial representation within RIDE. They referred to “

struggling to find all of [their] parts”, and their experience of being rejected based on the colour of their skin. A coloured woman stated:

“The RIDE once again made me aware of what I represent. It awakened a lot of feelings inside me. The most important was that childhood rejection of being coloured. It made me so angry, probably the most angry that I was in my entire life” [

1], p. 56.

The Indian female. They seem to be caught between tradition and the new demands to be powerful and part of the new dynamic, expressing anger and carrying the pain of not belonging or being acceptable (not being black) in the new dispensation. An Indian woman stated:

“from day one I was being told that I am not black. I lived my whole life knowing that I am black” [

1], p. 56.

The white male. Historically they were in power, the oppressors of others and were kept busy with the management of the country. It seemed as if they were unable to make contact with others, they appeared disempowered and often not heard by others. They seem to operate from the periphery. A white man stated: “

At a certain time in the programme I was really down and it felt as if there is no future for white (men) in the country”. They also reported being pushed into offices at work which are out of reach from others and which make contact difficult. They seem to represent the shame of the past [

1], p. 57. Two white men fell while walking during the first event—that could point to a lack of balance, where they felt disconnected from others, within the new South African dispensation [

8]. Furthermore, it could represent an experience of their disempowerment in the new dispensation marked by the fall of apartheid.

The white female. They seemed to have difficulty adapting to the new male role in the system. They were disillusioned towards white men and expressed their anger towards them for allowing the discrimination of the past. A white woman stated:

“Interesting for me was the anger I experienced against the white males who with their big mouths sat in the group and didn’t say a thing. Only afterwards they have a lot to say, but when they are back in the group they are silent. It is as if they are afraid of the black males” [

1], p. 57.

It seemed that the RIDE society was perpetuating a new dispensation with the difference that black males are now at the top. The RIDE society possibly did this in reaction to the apartheid dispensation with white males who were in power and other race groups having descending power and different control in relation to the white culture, as well as other cultures in the South African society. The message was clearly sent that they will not give up their newly found position on top of the ladder soon. A heated debate on the right to be called “black” or “African” vividly illustrated this struggle. Black participants heavily opposed the notion of white, coloured, or Indian people calling themselves African. By refusing other groups the right to be “African” or “black”, the black participants indirectly told the other groups that they would neither share their identity nor their position of power.

Although gender issues were also dealt with, gender played a secondary role and was seen to be only “women’s issues”. The men seemed to disown gender issues by projecting them onto the women. A black man stated: “What worried me (male) is that the gender issues, particularly the women have a lot of problems with it still.” The way the men disassociated themselves from the gender issues is not surprising, considering the idea that men have traditionally been the oppressor, while women have been the oppressed. The result is that only the oppressed are motivated to address issues relating to discrimination.

The notion that gender issues are women’s issues and should be worked on by women on behalf of the total system were further emphasised during the intergroup event, when an exclusive women’s group formed and found themselves sitting in the kitchen of the house used as one of the venues in a RIDE. I consulted this female group. Half of the women were black and half were white. After some discussion, two black women were sent out with a message to the larger system. Additionally, the next comment may be shocking to you, but as the black women were sent out I offered the interpretation based on what I saw unfolding in front of me that “Now the madams have sent the maids to do the work.” All the women were incensed by this interpretation and I was under verbal attack from them for making such an interpretation after they have worked so hard to complete the task of the intergroup. For me, it remained evident that the women’s group, instead of rallying together, had so much internal conflict and power struggles (race related) that their functioning was derailed. This may indicate that race-related issues in relation to who has the most power were once again predominant, even in the exclusive women’s group that wanted to rally together to fight for their cause. This reiterates the view that that South African society at that point of our journey found it difficult to move beyond race [

3,

9].

Based on the above discussion about how race was used in the RIDE society to position different groups, I hypothesise.

In the old dispensation a particular race hierarchy existed in the unconscious, i.e., white people being superior, with Indian, coloured, and black people carrying varying degrees of inferiority. In the new dispensation, we are possibly renegotiating the position of the race groups on a conscious and an unconscious level. These renegotiations may be attempts at reversing the roles among the race groups in the unconscious, i.e., black people being superior with Indian, coloured, and white people carrying varying degrees of inferiority. Although the socio-political dispensation has changed, in the South African psyche there is still investment about positioning different race groups in the unconscious in order for particular groups to be containers for our unacceptable parts [

2]. In other words, before 2008, we South Africans may have been negotiating (in the unconscious) about which race groups would be the containers for our incompetence and inferiority. The aforementioned may also denote a shift in the power dynamics, i.e., the white males were in power in the previous dispensation, and in the recent RIDEs race and gender being used to understand the power of the different sub-groups in the new dispensation.

Please bear in mind that these diversity dynamics were evident at the beginning of the RIDE journey, probably in relation to the high-power distance in the South African culture. As the journey continued it seemed as if the RIDE citizens could move to other diversity dynamics, which pointed to a willingness to work with the complexity of diversity which was denied to South Africans during the old dispensation.

3.4. Diversity Dynamics Evident in Recent RIDEs

The following overview is based on a presentation by May, De Klerk, Motswoaledi, and Pretorius made at the annual conference of the Society for Industrial and Organisational Psychology in South Africa in 2013, as well as on Thabo Mofomme’s and my own subsequent reflections. In the following section, I will show how the RIDE society in more recent years has journeyed from focusing on race to other diversity preoccupations which may indicate a shift in apartheid power dynamics or alert us to power dynamics that we were not focusing on due to an initial pre-occupation with white males’ power in the apartheid dispensation.

3.5. Searching for the-Absent-White-Man

As fewer and fewer white men attended RIDE towards 2010, a new dynamic appeared, viz “looking for the white man.” The questions pertaining to “where is the white man?” or “why is the white man not here?” were asked on several occasions in the large study group (LSG) since 2010. All the participants and usually three consultants are present in the LSG studying the diversity dynamics of the entire system. It seemed that organisations mainly sent those who formed part of their employment equity committees to RIDE and somehow this meant that only a few white men attended. The dynamic is significant because in 2011 only one white woman, one coloured woman, and one Indian woman attended. In 2012, only three white women, one coloured woman, and one Indian woman attended. In 2013, there were no white women and no coloured or Indian person and no one asked: “where are they?” or “why are they not here?”. In a recent RIDE, when only one white man attended, during the intergroup and institutional event members formed groups called the elephants, the giraffes, and springboks. In the institutional event the springboks became “the mighty springboks”. Afterwards, discussing the dynamic “of the-absent-white-man” with a colleague, she commented “there he is—the mighty springbok”.

Thus, in the recent RIDE societies it appeared as if members replaced their “race preoccupation” by a preoccupation with “searching for the-absent-white-man.” This absence possibly caused confusion, because white men as our familiar receptacles for rage were not available to identify with these projections. It seems that “the-absent-white-man” is used as a trump card which RIDE citizens keenly played when they did not want to work with other challenging diversity dynamics that were present between themselves. Differently put, “the-absent-white-man” is a defended position used to skirt the responsibility of dealing with other diversities. I also hypothesise that this dynamic is an unconscious wish, to have a conversation with “the white-man-in-the-mind” and based on this conversation to explore whether a real connection, a good-enough relationship, can be formed with him. This unconscious wish for a good-enough relationship with the white man may contain our need to make good-enough relationships with those across difference. It is almost as if we have a fantasy that if we can manage the relationship with him, we can manage the relationship with anyone across difference.

3.6. Studying Leadership across and within Groups

In a more recent RIDE, during the sessions of the LSG, it seemed that the RIDE citizens wanted to explore leadership and diversity. The members studied female leadership across different race groups, male leadership within the same race group and leadership across different race groups and gender. This was evident from looking at whom the members placed at the beginning of the spiral. The chairs in the LSG are arranged in unusual configurations, usually a spiral—20 or more participants sit in a spiral. Please bear in mind that one of the assumptions for the LSG is that where you are placed in the spiral (where you sit in the LSG) is an unconscious group dynamic and has meaning that can be interpreted.

3.7. Engaging the Black Male Leader

In the LSG of a recent RIDE, it was evident that members wanted to study black male leadership, because they placed two black men at the beginning of the spiral. It seemed, to the consultants, as if the two black men represented Mandela and Zuma. I believe that members wanted to learn more about how these black leaders will treat and work with them—having messianic fantasies that these black male leaders will save them from the hard work that needs to be done, whether in the LSG or in South African organisations and society. Perhaps the members also wondered whether these leaders were good-enough, especially in the light of what we see in the exercising of leadership by black males in our daily lives. It can also be speculated that members felt some envy in the light of the mantle of leadership being bestowed upon the black man.

3.8. Male and Female Leadership across Different Race Groups

In another LSG session of the same RIDE, two of the consultants (a black woman and a white man) were placed in the first two chairs of the spiral. I believe that members wanted to learn more about how these leaders will treat and work with them—having messianic phantasies that the pair, across difference, will save them from the hard work that needs to be done whether in the LSG or in South African organisations and society. Perhaps they were also wondering what the pair, across difference, can create together, and whether they can work together and not be overwhelmed by conflict emanating from their differences.

3.9. Female Leadership across Race Groups

In the last LSG of the same RIDE, after we were seated, the consultants noticed that the first nine seats of the spiral were occupied by women—more or less in the following order: first chair a white woman, second chair a coloured woman, and third chair a black woman, who was a tea lady in her organisation. Bearing in mind that Julius Malema was reported in the media as referring to Lindiwe Mazibuko as a tea lady, it was clear that Zille, De Lille, and Mazibuko were seated in the first three chairs of the spiral. The next three seats seemed to represent the same three female leaders, as did the next three seats. We, the consultants, understood that the RIDE citizens wanted to study female leadership across race and age differences in South Africa by placing the three “DA female leaders” in the first nine seats of the spiral. Possible questions that we heard the RIDE citizens ask were:

Are female leaders, especially black female leaders, good enough?

Should the women not be adhering to traditional societal roles rather than interfering in the domain of men?

How can women across race and age differences work together as leaders, and what kind of leadership can they offer us?

3.10. The Oppressor within: Exploring Diversity within the Same Race Group

A matter that has been skirted for quite some time by RIDE citizens is the diversity which exists within the same racial group. It was evident that members experienced difficulties in engaging with diversity within the same race group, especially members enjoying higher status in their organisations or society interacting with members occupying lower hierarchal levels in their respective organisations or societies. I received unusual evidence of this diversity dynamic during a recent RIDE. I was consulting to one of the groups in the intergroup session on day two and three—both sessions were just after lunch. In both sessions I was so sleepy that I almost fell asleep. It was so evident that I could not stay awake that a member of the group in another event referred to the fact that the consultant was sleeping in their session. I could not understand my experience because this has never happened to me before. Then, I received feedback in the staff meeting (based on work during a processing event) that one of the wealthier, successful black women reported that during the intergroup she felt that she had to look after and care for the lower status members on behalf of the group. Based on this experience the wealthier, successful black woman also reported that she could not connect authentically with black female members occupying lower positional levels in their respective organisations. It seems as if black female leaders/managers or those occupying higher echelon positions were acutely aware of their inability to relate to black women occupying lower positions and this created a somewhat debilitating effect on learning. There was some stuckness and not knowing how to handle this. It smacked of shame and guilt. This could also be a surprising discovery about our own resistance to change when we work with the unconscious, in that whereas we thought we were okay, it turns out we are not. This dynamic also alerted the staff about how we overlooked those (black) women occupying lower positions by keeping the language too technical for them. Once these (black) women could express themselves, they were quite actively involved in the process, suggesting that it was not inability or lack of interest on their part, but that we (the staff) also excluded them from participating.

In light of the above, I understood that this exploration of differences in racial sameness across position and socio-economic circumstances was the taboo in the room, and that it was so unspeakable that even I had to defend against it (by struggling not to fall asleep). Thus, in the more recent RIDE societies there may have been denial of discrimination based on status, with the refrain “I don’t participate in status discrimination, it is others…” This sounds like “I am not a racist, it is others…”.

Linked to this diversity dynamic of (not) dealing with diversity within racial sameness, was the difficulty for RIDE citizens to acknowledge and deal with other oppressions than that of white on black, e.g.,

The difficulty of black women in higher organisational positions to communicate with black women in lower organisational positions;

The oppression of black women by black men;

Conflict between different ethnic groups in South Africa.

By denying oppression amongst black people, discrimination is projected as only existing between races, with white people seen as the only discriminators. Through this projection, the black group can deny any conflict amongst them, preserve the apparent solidarity among themselves, and preserve themselves as good and white people as bad.

It is important to understand that this dynamic of denying diversity in the same race group does not only belong to the black group. The black group was merely used by the RIDE society to be containers for studying diversity within a group sharing a particular diversity characteristic.

3.11. Intersection between Race, Gender, and Class

In a recent RIDE, I experienced a situation which pointed to the intersection between diversity characteristics, viz, race, gender, and culture. In a session, an incident was related about how a person can make serious mistakes when unfamiliar with cultural traditions. Members coming from the same organisation, a black man, a white man, and a black woman, went to a meeting in rural Transkei. The villagers were waiting for them with the men seated on the one side and the women on the other. The white man wanted to go and sit where the women were seated, but the black man urgently gestured to him that he must join the men. I believe that the member related the incident, on behalf of all the participants, to communicate to me in particular and the other women in general that as a woman I should know my place and remain silent while the men attended to serious matters. I venture further to suggest that the unconscious wish among members could have been that my colleague Thabo Mofomme should be the director and not me.

In a later LSG, the group members started to speak in Sotho—it was a serious interchange which I did not understand. I was beginning to feel panicky because I could not assist my colleague, but I thought “Everything is in order. Because of his wealth of experience he will deal with the situation”. As I became more and more concerned because I was not able to make a useful contribution, a young Xhosa woman stood up and said somebody should translate because she did not understand what was going on. As you may realize, this was quite a relief to me and I thought, “Oh this is okay, I am not the only one who does not understand”. The next moment the black man at the beginning of the spiral left the room and the man on the second chair turned to whom we presumed was the oldest woman in the room to ask her about the role of women in the culture. She explained a woman’s role and then this was translated. The next moment my colleague turned to me and explained to me (and obviously to those who also did not understand) that this was a lekgotla, where the men could speak and the women had to remain silent. When the chief left (the man at the beginning of the spiral) the women were permitted to speak, but only after being asked by the motlatsa mookamedi (the second in charge), and then only the eldest woman in the group was permitted to speak. Based on what my colleague said, and the visual unfolding of the scenario, I understood and made the interpretation that based on culture, the women in the lekgotla had, in quite a sophisticated manner, been silenced by the men. It is significant to think that in this interaction the black group used the diversity characteristics of gender, culture, position, and age to silence 50% of the RIDE citizens in the LSG.

Based on the containment provided by my colleague and me, and the particular interpretation I made, it seemed that the work done by the men and the complicity of the women with the men in ensuring that the women remained silent could be seen as a diversity dynamic by the participants. This could have been a moment where the members could tolerate seeing an anxiety-provoking diversity dynamic because of being contained by RIDE and the consultants. Further evidence of this experience of containment came from a discussion about gender violence in the next LSG, where participants could acknowledge that the violence does not only entail men physically abusing women, but also women physically abusing men. In the conversation it felt as if men and women could hear each other differently or clearly across the gender divide—as if they could make space for each other’s pain and rage. I propose that perhaps these participants, through their experiences in this RIDE, developed their own capacity for reflecting on anxiety-provoking aspects [

29,

30] pertaining to some of their diversity dynamics.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, I highlight a number of key insights or speculations gained from the shared reflections about diversity dynamics. These key points have been selected in the hope of thinking about how we can use this understanding in our organisations as educationists, managers, practitioners, and in society as citizens.

The above themes denote a journey of becoming aware of more diversity dynamics over a 13-year period of presenting RIDE first possibly as a shift in apartheid power relations and later focusing beyond this initial pre-occupation with white males’ power in the apartheid dispensation. It seems that through RIDE as a container, the consultants as containers, and the willingness of the participants to engage with their diversity challenges, more diversity dynamics have become accessible to the RIDE citizens. Through this we have become less stuck and less overwhelmed by a single (race) preoccupation. It also appears we have moved towards another pre-occupation, i.e., “the-absent-white-man” as a container for our wish to form good-enough relationships with those with whom we have difficulty connecting across difference. Although the black group seemed to be a container in recent RIDEs for working with diversity dynamics within a race group, this may denote an unconscious realisation that as South Africans we should also be working with differences in the same group. It also seems that we are exploring our relationships with leaders across and within (racial) differences. As the RIDE participants became more aware of these diversity dynamics, they could work more effectively with the marginalisation of groups through the intersection between diversity characteristics.

You may think that this is not a shift in the diversity dynamics, but an unhappy condition where we merely became aware of more diversity dynamics which we should work with. However, I hypothesise that, through the RIDE journey there appears to be a movement or shift from initial RIDEs in which participants projected the denigrated parts of themselves and their group into and onto other individuals and groups, to the more recent RIDEs where members seem to acknowledge and explore the denigrated parts in themselves and their own groups—perhaps to integrate the denigrated part with the idealised part within themselves. This seems to be a more layered and complex understanding of oneself and one’s diversity dynamics.

It is also important to realise that through RIDE as a container, the consultants as containers for more diversity dynamics have become accessible to the RIDE citizens and through this they have become less stuck and overwhelmed by a single race preoccupation. Perhaps the members have seen through the consultants’ calmness and self-reflecting stance in the presence of overwhelming rage and dread generated by the race preoccupation that they can tolerate the anxiety, pain, and rage elicited as they become aware of diversity dynamics and their complicity with these dynamics. I hypothesise that through experiencing RIDE and the consultants as good-enough containers the members develop their own capacity for reflecting on anxiety-provoking, enraging and distressing aspects [

29,

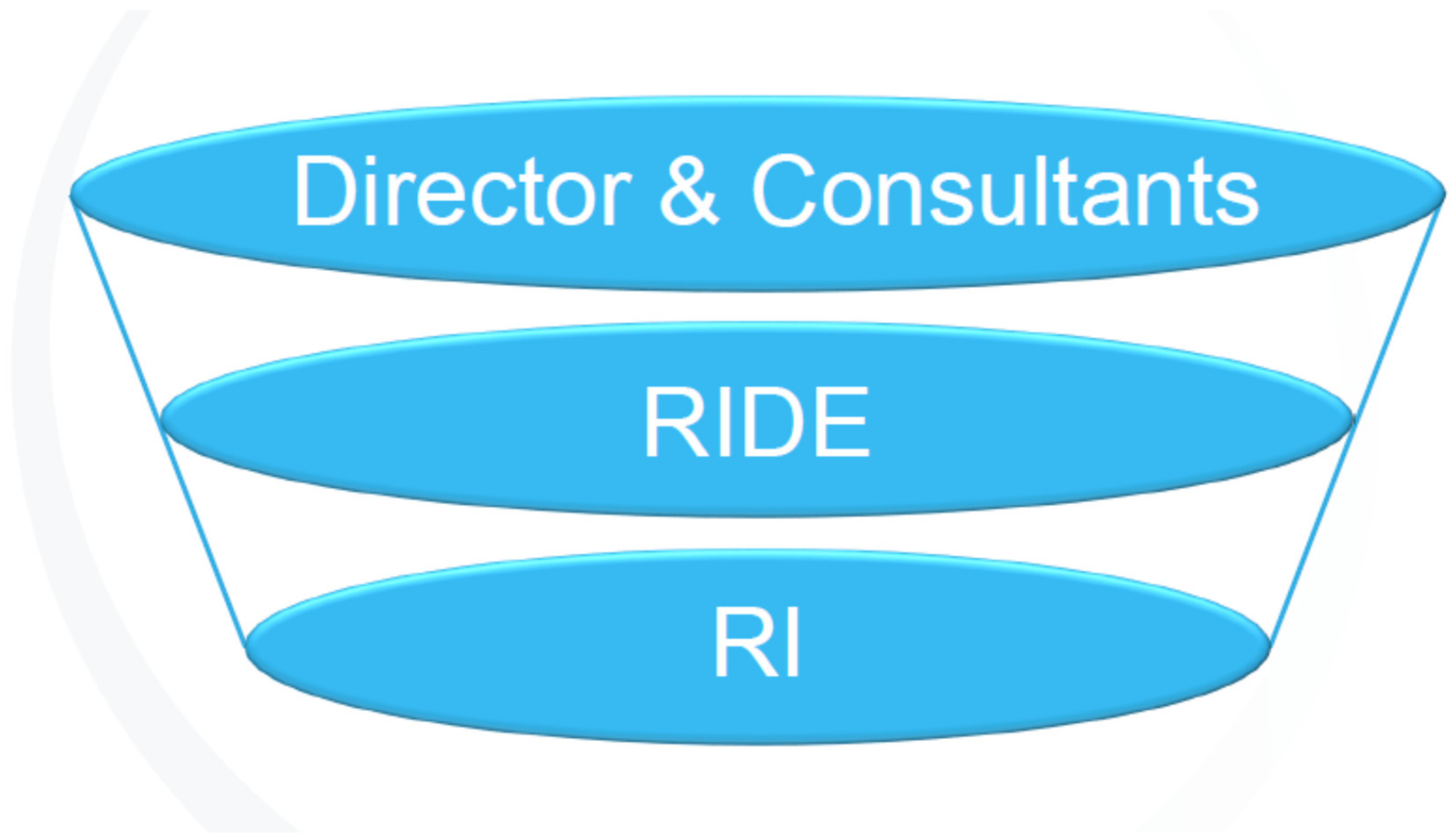

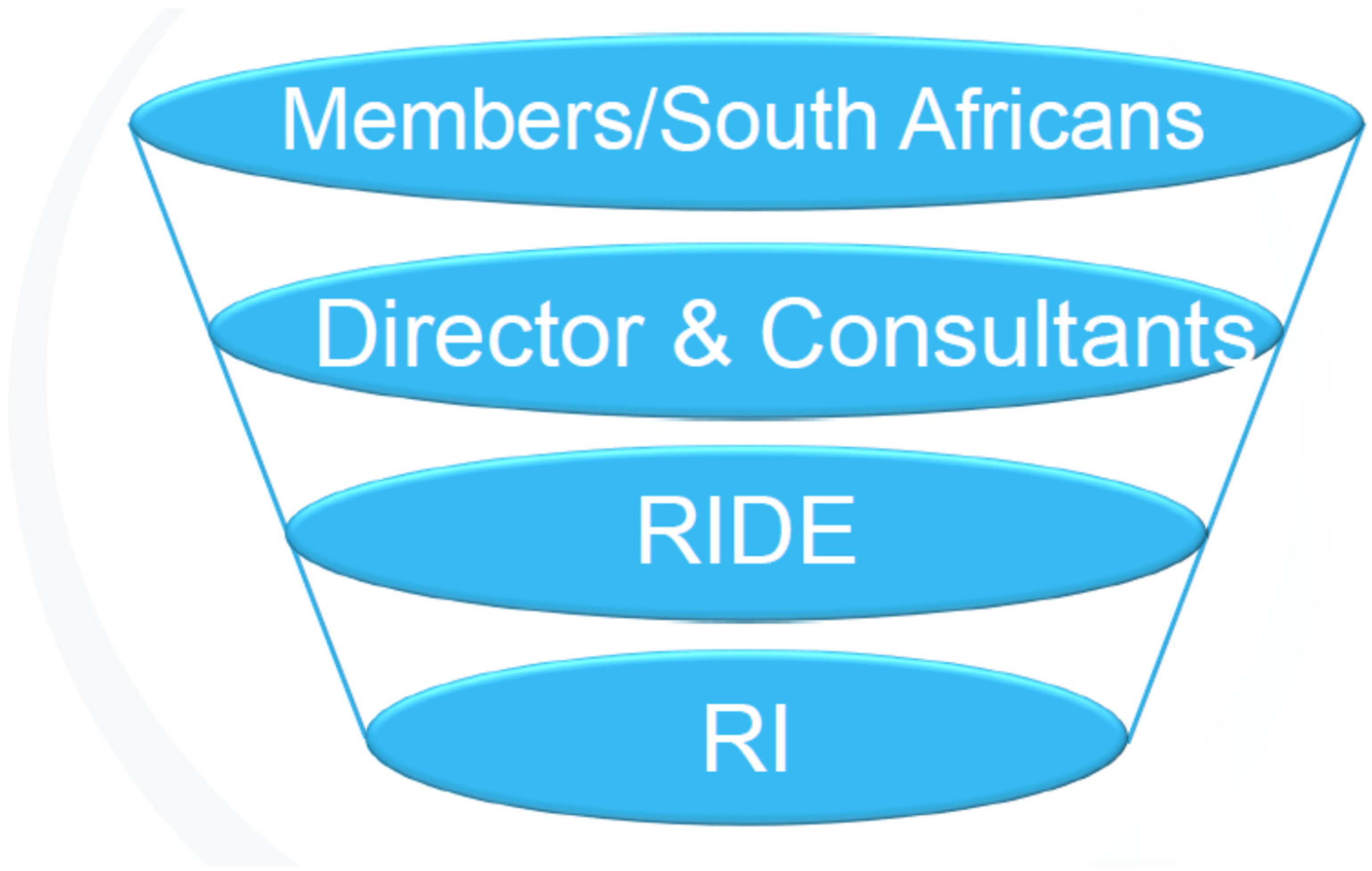

30] pertaining to diversity dynamics. In other words, by participating in RIDE, participants have moved from dumping their denigrated parts into and onto others, to reintegrating these parts with the idealised parts in themselves. Thus, hopefully moving beyond not merely spitting out/projecting into or onto others their unresolved diversity challenges. In other words, as South Africans we cannot get rid of our diversity dynamics, but we can learn to contain and integrate these diversity dynamics within ourselves and not dump our denigrated parts onto and into other South Africans as illustrated through

Figure 2.

The importance of understanding the diversity dynamics operating in the relationship between individuals, between groups and in organisations in South Africa has been highlighted. In education, the understanding about diversity dynamics can be used by management to form a different awareness of conscious and unconscious factors impacting on the relationship between stakeholders and subsequently on the effectiveness of these stakeholders in their respective roles. This understanding about diversity dynamics also opens up the opportunity for stakeholders to explore how the different problems in the education landscape result not only from historical factors, but also from the diversity dynamics operating among themselves [

2,

8]. Other South African organisations should approach diversity not in a mechanistic manner, using instructional methods, such as lectures and presentations, but in a dynamic and experiential manner, such as using the group relations training model in interventions. Although participants in such events will experience resistance, opportunities for accepting personal responsibility for their positions and actions around diversity will be created [

3]. Further, diversity interventions based on the group relations training model should be used in conjunction with other approaches, such as the socio-cognitive and legal imperatives currently used in organisations in order to optimise the management of diversity. It is thus not a case of opting for one or the other approach, but of using them together in order to gain a more comprehensive understanding of diversity, and therefore being able to manage more effectively.

I would like to return to the rock pile that was started by Mr. Mandela on Robben Island (

Figure 3). I think of each one of the diversity dynamics that we now have access to as a rock that the RIDE citizens have placed on the rock pile. I imagine us now being able to place not only race but also gender, organisational position, socio-economic status and cultural group on this memorial and we build a society that is now free for the first time to really be cognisant of a range of diversity dynamics. I envisage that other South Africans through their relationship building across difference in communities, corporate life, the public sector, educational institutions, spaces such as RIDE, and in the different spheres of their daily lives will add to our understanding of and access to our diversity dynamics. Drawing on the symbolic value of building a rock pile while journeying, I suggest that the RIDE citizens have assisted us by starting a rock pile that we can all add to as we learn about our own diversity dynamics and work with these in the South Africa we find ourselves in every day. Considering this rock pile and the work that has been done before us, this rock pile will assist us not to lose our way as we learn to build relationships across difference. Furthermore, through this rock pile made up of South African diversity dynamics we acknowledge the sweat and toil by those during RIDE and other South Africans and we draw on what they have learnt to continue our journey of dealing with diversity challenges in our efforts to become an integrated nation