Desire for Genital Surgery in Trans Masculine Individuals: The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Transnormativity and Trans Positive Identity

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Crisis of the Clinical Perspective on Gender Dysphoria

1.2. Gender Dysphoria, Desire for Medical Affirmation Treatments, and Psycho-Social Constructs

1.3. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.3. Data Analysis

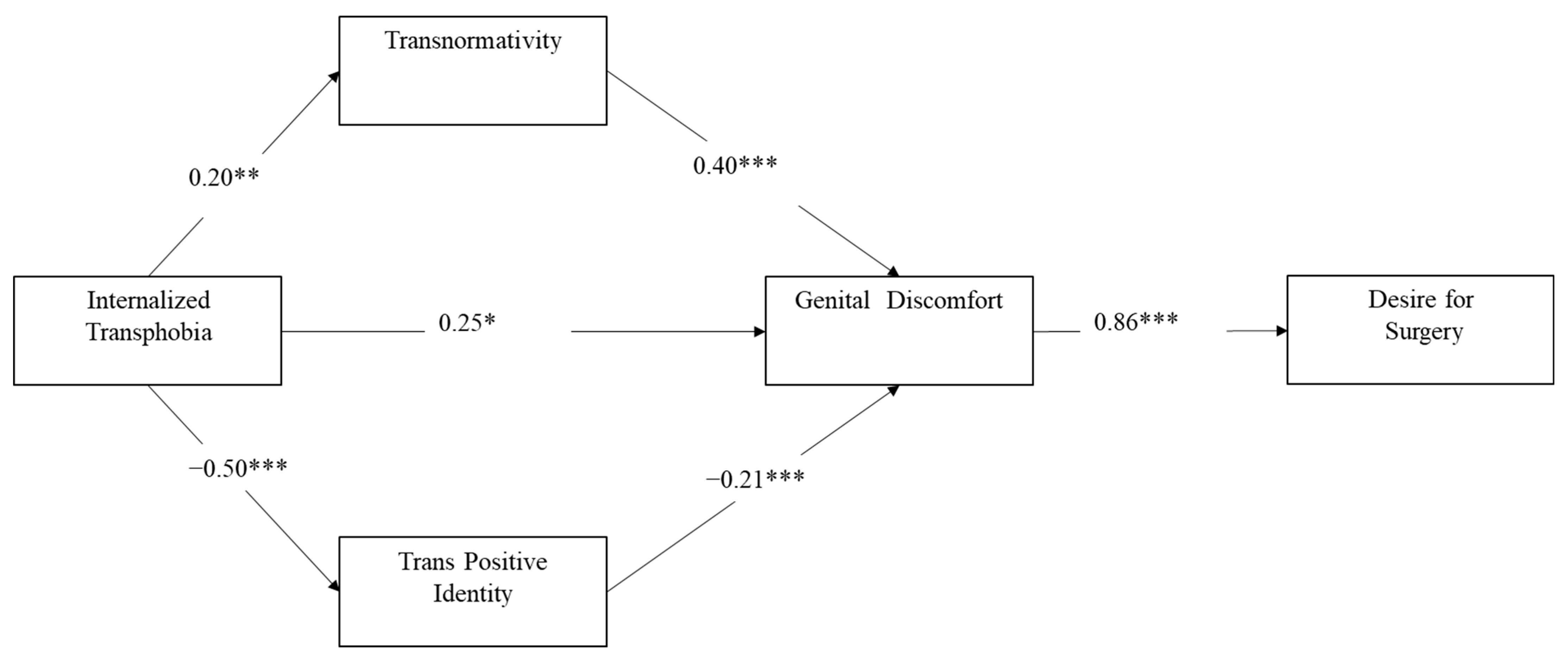

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Data Transparency

Appendix A

- Trans man takes testosterone. (L’uomo trans assume testosterone.)

- Trans man undergoes top surgery (mastectomy). (L’uomo trans si sottopone alla top surgery (mastectomia).)

- Trans man do not consider their transition complete until they undergo phalloplasty. (L’uomo trans non considera la sua transizione completa fino a che non si sottopone a falloplastica.)

- The trans man makes a complete transition to masculinity. (L’uomo trans compie una transizione completa al maschile.)

- Trans men have a binary view of gender (you’re either a man, or you’re a woman). (Gli uomini trans hanno una visione binaria del genere (o sei uomo, o sei donna).)

- A gender fluid or non-binary person deserves less respect than a binary trans man. (Una persona gender fluid o non binaria merita meno rispetto di un uomo trans binario.)

- Non-binary people are trans-binary people who are not brave enough to admit it. (Le persone non binarie sono persone trans binarie che non hanno abbastanza coraggio da ammetterlo.)

- Those who identify as nonbinary are probably just undecided between being male or female. (Chi si identifica come non binario è probabilmente solo indeciso tra essere uomo o donna.)

- Non-binary people are simply confused about their gender identity. (I non binari sono semplicemente confusi sulla loro identità di genere.)

- Trans men have always felt male, from very early childhood. (Gli uomini trans si sono sempre sentiti maschi, fin dalla primissima infanzia.)

- Trans man always knew he was trans. (L’uomo trans ha sempre saputo di essere trans)

- Trans identity is most authentic when present from an early age. (L’identità trans è più autentica se presente fin dalla più tenera età.)

- Trans men were born in the wrong body. (L’uomo trans è nato nel corpo sbagliato.)

- Being a trans man is not a choice, you are born that way. (Essere un uomo trans non è una scelta, si nasce così.)

- Trans men act like cis men. (L’uomo trans si comporta come un uomo cis.)

- A trans man is completely masculine in mannerisms, attitudes, interests, etc. (L’uomo trans è completamente maschile nei modi, atteggiamenti, interessi, ecc.)

- The trans man is mistaken by everyone for a cis man. (L’ uomo trans viene scambiato da tutti per un uomo cis.)

- The transition can only be considered satisfactory when the passing is constant. (La transizione può considerarsi soddisfacente solo quando il passing è costante.)

References

- American Psychological Association. Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming People. Am. Psychol. 2015, 70, 832–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindley, L.; Galupo, M.P. Gender Dysphoria and Minority Stress: Support for Inclusion of Gender Dysphoria as a Proximal Stressor. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2020, 7, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, M.L.; Testa, R.J. A Conceptual Framework for Clinical Work with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Clients: An Adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2012, 43, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Davy, Z.; Toze, M. What Is Gender Dysphoria? A Critical Systematic Narrative Review. Transgender Health 2018, 3, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulice-Farrow, L.; Cusack, C.E.; Galupo, M.P. “Certain Parts of My Body Don’t Belong to Me”: Trans Individuals’ Descriptions of Body-Specific Gender Dysphoria. Sex Res. Soc. Policy 2020, 17, 654–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, R. The Classification and Labeling of Nonhomosexual Gender Dysphorias. Arch. Sex Behav. 1989, 18, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssmann, C. Passing Torches? TSQ Transgender Stud. Q. 2016, 3, 120–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssmann, C. Care in Transit: The Political and Clinical Emergence of Trans Health. Ph.D. Thesis, University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Budge, S.L. Psychotherapists as Gatekeepers: An Evidence-Based Case Study Highlighting the Role and Process of Letter Writing for Transgender Clients. Psychotherapy 2015, 52, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bockting, W.; Coleman, E.; Lief, H.I. A Comment on the Concept of Transhomosexuality, or the Dissociation of the Meaning. Arch. Sex. Behav. 1991, 20, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galupo, M.P.; Pulice-Farrow, L. Subjective Ratings of Gender Dysphoria Scales by Transgender Individuals. Arch. Sex Behav. 2020, 49, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; vanGoozen, S.H.M. Sex Reassignment of Adolescent Transsexuals: A Follow-up Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deogracias, J.J.; Johnson, L.L.; Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F.L.; Kessler, S.J.; Schober, J.M.; Zucker, K.J. The Gender Identity/Gender Dysphoria Questionnaire for Adolescents and Adults. J. Sex Res. 2007, 44, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, B.A.; Veale, J.F.; Townsend, M.; Frohard-Dourlent, H.; Saewyc, E. Non-Binary Youth: Access to Gender-Affirming Primary Health Care. Int. J. Transgend. 2018, 19, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galupo, M.P.; Pulice-Farrow, L.; Lindley, L. “Every Time I Get Gendered Male, I Feel a Pain in My Chest”: Understanding the Social Context for Gender Dysphoria. Stigma Health 2020, 5, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, J.K.; Doty, J.L.; Catalpa, J.M.; Ola, C. Body Image in Transgender Young People: Findings from a Qualitative, Community Based Study. Body Image 2016, 18, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, H. The Transsexual Phenomenon. Trans. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1967, 29, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beek, T.F.; Kreukels, B.P.C.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Steensma, T.D. Partial Treatment Requests and Underlying Motives of Applicants for Gender Affirming Interventions. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 2201–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prunas, A.; Fisher, A.D.; Bandini, E.; Maggi, M.; Pace, V.; Todarello, O.; De Bella, C.; Bini, M. Eudaimonic Well-Being in Transsexual People, Before and after Gender Confirming Surgery. J. Happiness Stud. 2017, 18, 1305–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byne, W.; Karasic, D.H.; Coleman, E.; Eyler, A.E.; Kidd, J.D.; Meyer-Bahlburg, H.F.L.; Pleak, R.R.; Pula, J. Gender Dysphoria in Adults: An Overview and Primer for Psychiatrists. Transgend. Health 2018, 3, 57-A3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Hidalgo, M.A.; Leibowitz, S.; Leininger, J.; Simons, L.; Finlayson, C.; Garofalo, R. Multidisciplinary Care for Gender-Diverse Youth: A Narrative Review and Unique Model of Gender-Affirming Care. Transgender Health 2016, 1, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellini, G.; Ristori, J.; Fisher, A.; Ristori, J.; Casale, H.; Carone, N.; Fanni, E.; Mosconi, M.; Jannini, E.; Ricca, V.; et al. Transphobia and Homophobia Levels in Gender Dysphoric Individuals, General Population and Health Care Providers. J. Sex. Med. 2017, 14, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.D.; Castellini, G.; Ristori, J.; Casale, H.; Giovanardi, G.; Carone, N.; Fanni, E.; Mosconi, M.; Ciocca, G.; Jannini, E.A.; et al. Who Has the Worst Attitudes toward Sexual Minorities? Comparison of Transphobia and Homophobia Levels in Gender Dysphoric Individuals, the General Population and Health Care Providers. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2017, 40, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, N.J.; Syed, M. Transnormativity and Transgender Identity Development: A Master Narrative Approach. Sex Roles 2019, 81, 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Budge, S.L.; Adelson, J.L.; Howard, K.A.S. Anxiety and Depression in Transgender Individuals: The Roles of Transition Status, Loss, Social Support, and Coping. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2013, 81, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galupo, M.P.; Bauerband, L.A.; Gonzalez, K.A.; Hagen, D.B.; Hether, S.D.; Krum, T.E. Transgender Friendship Experiences: Benefits and Barriers of Friendships across Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation. Fem. Psychol. 2014, 24, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggle, E.D.B.; Mohr, J.J. A Proposed Multi Factor Measure of Positive Identity for Transgender Identified Individuals. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riggle, E.D.B.; Rostosky, S.S.; McCants, L.E.; Pascale-Hague, D. The Positive Aspects of a Transgender Self-Identification. Psychol. Sex. 2011, 2, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzani, A.; Decaro, S.P.; Prunas, A. Trans Masculinity: Comparing Trans Masculine Individuals’ and Cisgender Men’s Conformity to Hegemonic Masculinity. Sex Res. Soc. Policy 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Amodeo, A.L.; Bochicchio, V.; Valerio, P.; Frost, D.M. Psychometric Characteristics of the Transgender Identity Survey in an Italian Sample: A Measure to Assess Positive and Negative Feelings towards Transgender Identity. Int. J. Transgenderism 2017, 18, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Testa, R.J.; Habarth, J.; Peta, J.; Balsam, K.; Bockting, W. Development of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2015, 2, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behling, O.; Law, K.S. Translating Questionnaires and Other Research Instruments: Problems and Solutions; SAGE: Newcastle, UK, 2000; ISBN 9780761918240. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.A.; Bouman, W.P.; Haycraft, E.; Arcelus, J. The Gender Congruence and Life Satisfaction Scale (GCLS): Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Outcomes from Transgender Health Services. Int. J. Transgend. 2019, 20, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschfeld, G.; von Brachel, R. Improving Multiple-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis in R—A Tutorial in Measurement Invariance with Continuous and Ordinal Indicators. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2019, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scandurra, C.; Bochicchio, V.; Dolce, P.; Caravà, C.; Vitelli, R.; Testa, R.J.; Balsam, K.F. The Italian Validation of the Gender Minority Stress and Resilience Measure. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2020, 7, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmins, L.; Rimes, K.A.; Rahman, Q. Minority Stressors and Psychological Distress in Transgender Individuals. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2017, 4, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hatzenbuehler, M.L. How Does Sexual Minority Stigma “Get Under the Skin”? A Psychological Mediation Framework. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 135, 707–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, N.J.; Johnson, A.H. Transnormativity. In The Sage Encyclopedia of Trans Studies; Sage Publication: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2021; pp. 869–871. [Google Scholar]

| Total Sample (N = 127) N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Social transition | |

| Coming out to family members | 102 (80.3) |

| Coming out to friends | 119 (92.9) |

| Coming out with school mates/colleagues | 76 (59.8) |

| Chose different name | 115 (90.5) |

| Changed name legally | 18 (14.2) |

| Wearing clothes that reflect GI in public | 121 (95.3) |

| Wearing clothes that reflect GI at work/school | 118 (92.9) |

| Changed gender legally | 18 (14.2) |

| Medicalized transition | |

| Top surgery | 18 (14.2) |

| Bottom surgery (penile reconstruction) | 1 (0.8) |

| Voice Therapy | 8 (6.3) |

| HRT (Testosterone) | 55 (43.3) |

| Hysterectomy | 12 (9.4) |

| Total Sample N = 127 | Binary N = 112 | Non-Binary N = 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | M = 26.90 (SD = 9.93) | M = 26.53 (SD = 9.91) | M = 29.78 (SD = 9.93) |

| Sexual Orientation; n (%) | |||

| Asexual | 3 (2.4) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (13.3) |

| Bisexual | 21 (16.5) | 19 (17.0) | 2 (13.3) |

| Fluid | 4 (3.1) | 4 (3.6) | - |

| Gay | 11 (8.7) | 10 (8.9) | 1 (6.7) |

| Heterosexual | 36 (28.3) | 36 (32.1) | - |

| Pansexual | 28 (22.0) | 24 (21.4) | 4 (26.7) |

| Queer | 10 (7.9) | 7 (6.3) | 3 (20.0) |

| Other | 10 (7.9) | 8 (7.1) | 2 (13.3) |

| Education Level; n (%) | |||

| Secondary School | 18 (14.2) | 17 (15.2) | 1 (6.7) |

| High School | 72 (56.7) | 66 (58.9) | 6 (40.0) |

| Graduate or post-graduate | 33 (26.0) | 26 (23.2) | 7 (46.7) |

| Marital Status; n (%) | |||

| Single | 95 (74.8) | 84 (75.0) | 11 (73.3) |

| Divorced/Separated | 2 (1.6) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (-6.7) |

| Cohabitant/Common-law couple | 25 (15.7) | 23 (20.5) | 2 (13.3) |

| Widow | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | - |

| Relational Status; n (%) | |||

| Committed | 38 (29.9) | 38 (33.9) | 3 (20.0) |

| Married | - | - | - |

| Dating | 8 (6.3) | 8 (7.1) | - |

| Polyamorous Relationship | 6 (4.7) | 4 (3.6) | 2 (13.3) |

| Non-consensual non-monogamy | 1 (0.8) | - | 1 (6.7) |

| Open Relationship | 6 (4.7) | 4 (3.6) | 2 (13.3) |

| Single | 57 (44.9) | 53 (47.3) | 4 (26.7) |

| Not interested in having a relationship | 9 (7.1) | 7 (6.3) | 2 (13.3) |

| Scales | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Transnormativity | - | 3.25 (0.76) | 1–5 | |||

| 2. Internalized transphobia | 0.28 ** | - | 2.65 (1.06) | 1–5 | ||

| 3. Trans positive Identity | −0.43 *** | −0.33 *** | - | 9.50 (1.63) | 1–7 | |

| 4. Surgery Procedure Desire | −0.25 ** | 0.14 | −0.29 *** | - | 0.49 (0.50) | 0–1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Anzani, A.; Biella, M.; Scandurra, C.; Prunas, A. Desire for Genital Surgery in Trans Masculine Individuals: The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Transnormativity and Trans Positive Identity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158916

Anzani A, Biella M, Scandurra C, Prunas A. Desire for Genital Surgery in Trans Masculine Individuals: The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Transnormativity and Trans Positive Identity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(15):8916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158916

Chicago/Turabian StyleAnzani, Annalisa, Marco Biella, Cristiano Scandurra, and Antonio Prunas. 2022. "Desire for Genital Surgery in Trans Masculine Individuals: The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Transnormativity and Trans Positive Identity" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 15: 8916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158916

APA StyleAnzani, A., Biella, M., Scandurra, C., & Prunas, A. (2022). Desire for Genital Surgery in Trans Masculine Individuals: The Role of Internalized Transphobia, Transnormativity and Trans Positive Identity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(15), 8916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19158916