Attachment Theory: A Barrier for Indigenous Children Involved with Child Protection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Attachment Theory

- An adult needs to have been present from the infant’s birth in order for an infant to form a secure attachment to that adult;

- The window of opportunity for the formation of a secure attachment endured only throughout the first three years of life;

- The amount of time spent with a child is the most important element in forming an enduring attachment relationship (p. 338).

- Universality in that children will become attached to one or more caregivers;

- Secure attachment is normative, but appears differently across cultures;

- Attachment relies upon sensitive and responsive parenting by caregivers;

- Child-rearing has no common standard, but varies across cultures; with sensitivity and responsiveness meaning quite different things in distinct cultural contexts;

- Competence in parenting may look different, and successful parenting outcomes are also different across cultures (pp. 134–135).

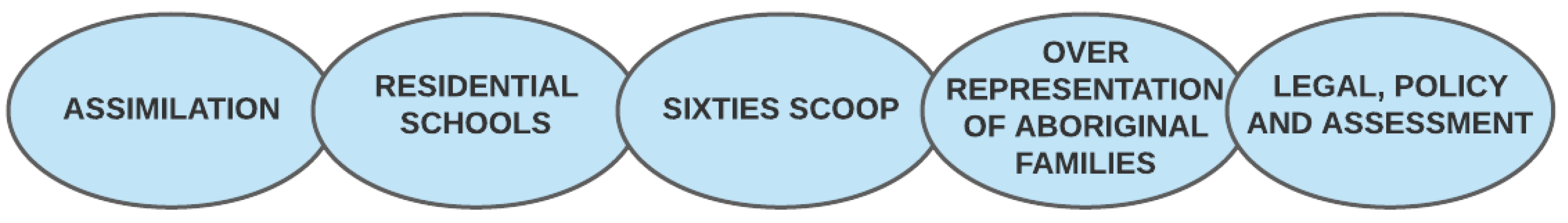

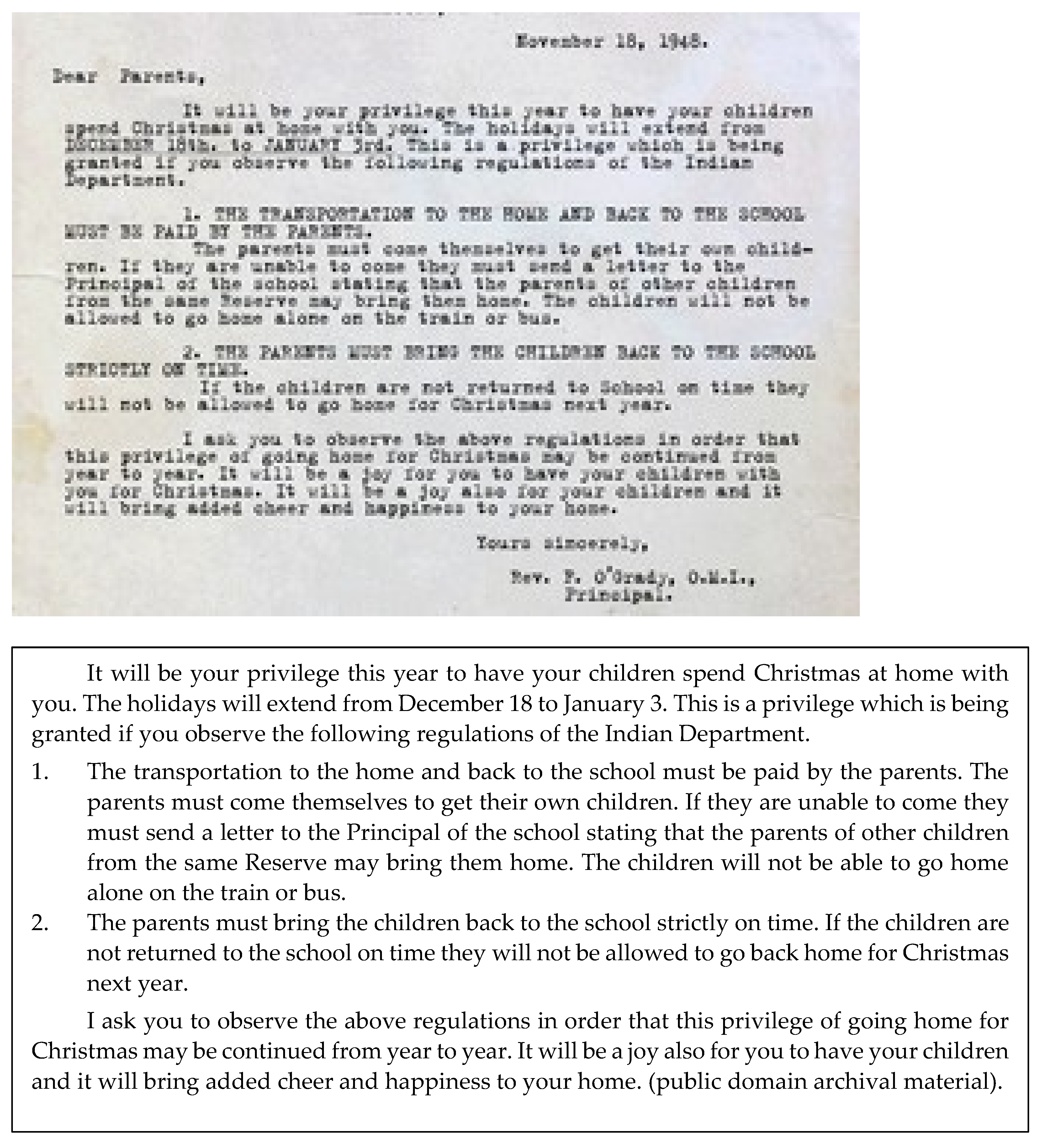

3. Indigenous Children in Care

“I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.”[29]

It is readily acknowledged that Indian children lose their natural resistance to illness by habitating so closely in these schools, and that they die at a much higher rate than in their villages. But this alone does not justify a change in the policy of this Department, which is being geared towards the final solution of our Indian Problem.[31]

4. Law, Policy, and Assessment

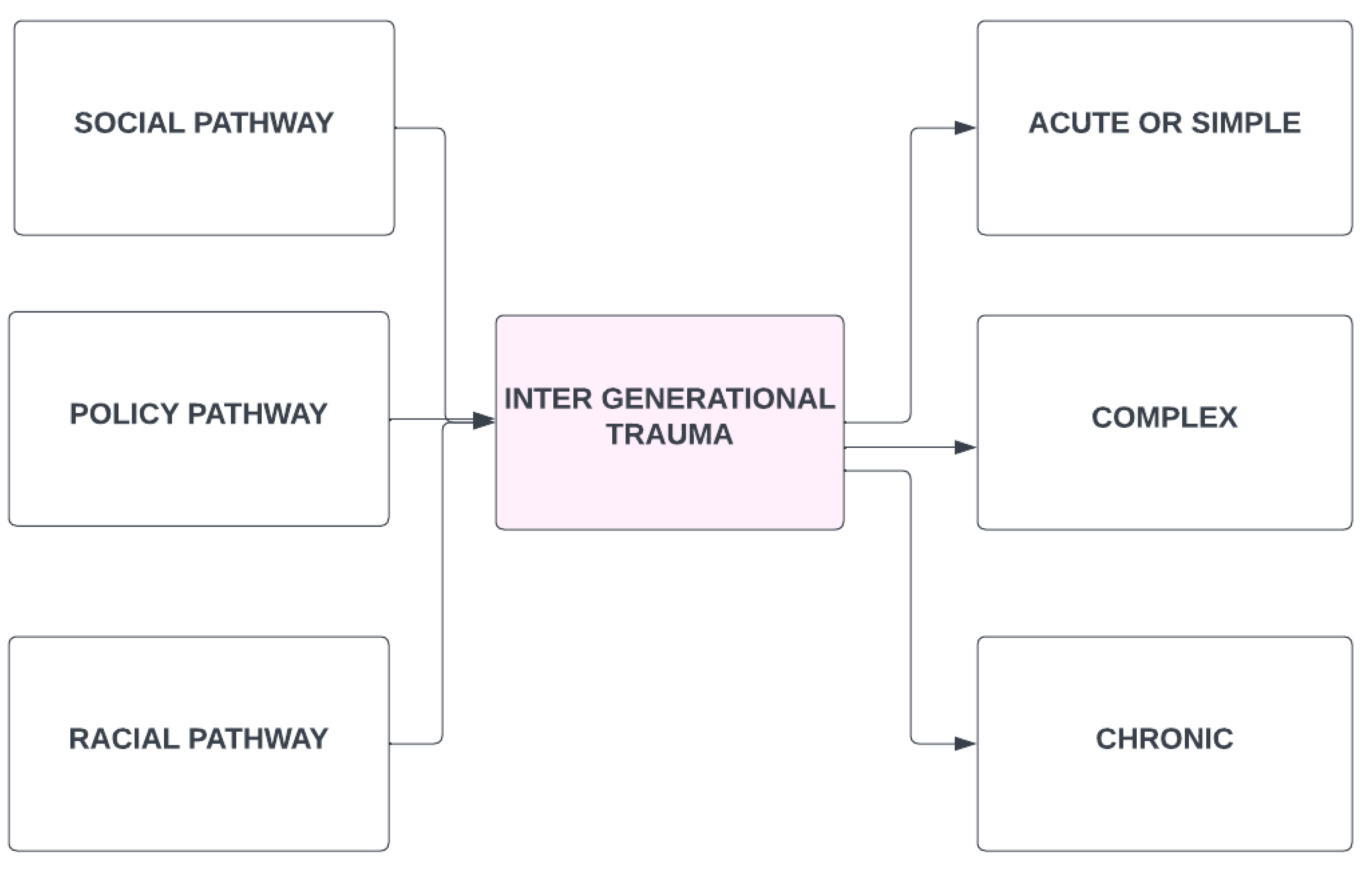

5. Intergenerational Trauma

6. Place of Attachment Theory

- The degree of trauma that is seen as lingering and still active in Indigenous communities is framed as a way to conceptualize the entire community as presenting risk to the child;

- Due to IGT and IRS, many families in Indigenous communities have a history of involvement in child protection. That history is seen as presenting a risk to the child even when that history might be old or clearly related to assimilation and colonization;

- It is easier to place a child in a non-Indigenous home, as most established foster placements are non-Indigenous, have been pre-screened, and are available to receive children;

- As child intervention has been heavily involved in Indigenous communities, those that may care for the child may themselves have prior child intervention involvement. This acts as a barrier for approval as a caregiver.

- All children form attachments, although the quality will vary from child to child and relationship to relationship. These differences will vary in expression, form, and function across cultures. Thus, Eurocentric definitions and assessments are incorrectly applied to Indigenous peoples in Canada [38,39,41,42,43].

- There is no universally accepted definition of attachment that applies across cultures. Indeed, there is a vibrant research base that shows that attachment variations exist not only in specific cultural contexts, but also that attachment varies from nuclear to communal to collectivistic arrangements [44,45].

- Attachment Theory was never meant to be used as the basis of child protection decision-making. Indeed, the leading researchers in attachment theory have made that clear [46,47]. Attachment has been used to incorrectly determine that, once a child is placed in a foster (to adopt) or longer-term placement, the child cannot move. Careful consideration has shown that children and adults do create a variety of attachments over the course of their development over a lifetime [48]. Indeed, Duschinsky noted:

Commentators have warned, however, that slippage between the broad and circumscribed use of the term ‘attachment disorder’ has contributed in some quarters to an overdiagnoses of attachment disorders, misuse of appeal to attachment disorder in psychological assessments for family courts and ‘neglect of children’s potential other psychological needs. The gap between clinical discourses and the research paradigm has also been filled at times by inappropriate use of disorganized attachment classification, forced to play the role of a quasi-diagnostic category in child welfare practice.[48] (p. 60)

7. Place of Attachment Theory

8. Psychological Parent

The phenomenon of attachment and bonding which society welcomes for its binding effect in early adoption is inconvenient in foster care. In recent years we have been made painfully aware that foster parents can become psychological parents and the objects of the foster child’s deepest attachment.

Foster parents have long been expected to keep in mind that their function is only temporary, that they should remain clear about their role and not become ‘possessive’. But no matter how conscientiously restrained a foster mother may try to be, if the child is very young, he will become attached to her and the absent mother will gradually slip into un- importance.[56]

9. Are Children Better off Growing up in Care?

10. Question of Identity

Yes, it would have made a difference given that it is another Blackfoot nation, so I would be learning Blackfoot ways of life and everything, which would be ideal given my circumstances. That would be better than going to a non-Indigenous home, but at the same time that’s not where I grew up. So, ideally, I would want to be with somebody who is either from Kainai, or who lives there, or who lives in a city but is from there and has connections to them. That would be ideal, but secondly, Siksika would be okay given that they are Indigenous. But then, at the same time, I’d still be different because I was from a different reserve…. whether it be somebody that maybe doesn’t have any relation to you, but that’s still like your family, they’re still from where you’re from, and have connections to that nation.[70]

11. Case Examples

There is also now strong recognition that cultural heritage is an important factor in determining what is in a child’s best interests. Article 20 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child provides that due regard shall be paid to the desirability of continuity in a child’s upbringing and to the child’s ethnic, religious, cultural and linguistic background. Nevertheless, as our case has clearly shown, there are still contentious questions in law about how much weight to place on a child’s Indigenous heritage when determining what is, in fact, in the best interests of the child.(Para. 222)

Has the state of the law changed since the decision in Racine v Woods? [74] All jurisdictions in Canada have now enacted child welfare legislation requiring judges and agencies to consider a child’s cultural heritage when making a decision regarding the child. The dilemma is how to properly weigh the Indigenous culture as a ‘best interests’ factor.(Para. 227)

The impact on the removed aboriginal children has been described as “horrendous, destructive, devastating and tragic.” The uncontroverted evidence of the plaintiff’s experts is that the loss of their aboriginal identity left the children fundamentally disoriented, with a reduced ability to lead healthy and fulfilling lives. The loss of aboriginal identity resulted in psychiatric disorders, substance abuse, unemployment, violence and numerous suicides. Some researchers argue that the Sixties Scoop was even “more harmful than the residential schools:[59] (Para. 7)

12. Discussion

13. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada; Truth and Reconciliation Commission: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2015.

- Bowlby, J. Forty-Four Juvenile Thieves: Their Character and Home Life; Baillière, Tindall and Cox: London, UK, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. The influence of early environment in the development of neurosis and neurotic character. Int. J. Psychoanal. 1940, 21, 154–177. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, H. Universality claim of attachment theory: Children’s socioemotional development across cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 11414–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss, Vol. 2: Separation; Basic Book: New York, NY, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Stroufe, L.A.; Waters, E. Attachment as an organizational construct. Child Dev. 1977, 48, 1184–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J. John Bowlby and Attachment Theory; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth, M.S. Attachment retrospect and prospect. In The Place of Attachment in Human Behavior; Parks, C.M., Stevenson-Hinde, J., Eds.; Tavistock: London, UK, 1982; pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Pietromonaco, P.R.; Barrett, L.F. The internal working models concept: What do we really know about the self in relation to others? Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2000, 4, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, M.; Hesse, E.; Hesse, S. Attachment theory and research: Overview with suggested applications to child custody. Fam. Court Rev. 2011, 49, 426–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosabal-Coto, M.; Quinn, N.; Keller, H.; Vicedo, M.; Chaudhary, N.; Gottlieb, A.; Scheidecker, G.; Murray, M.; Takada, A.; Morelli, G.A. Real-world applications of attachment theory. In The Cultural Nature of Attachment: Contextualizing Relationships and Development; Keller, H., Bard, K.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Stroufe, L.A. The role of infant-caregiver attachment. In Clinical Implications of Attachment; Belski, J., Nezowski, T., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillside, NJ, USA, 1988; pp. 18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bretherton, I. Communication patterns, internal working models, and the intergenerational transmission of attachment relationships. Infant Ment. Health J. 1990, 11, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, M.; Kaplan, N.; Cassidy, J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 1985, 50, 66–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Volume I: Attachment; The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis: London, UK, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J. Attach. Loss Vol. 3: Loss Sadness Depress; Hogarth Press: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, H.; Chaudhary, N. Is the mother essential for attachment? Models of care in different cultures. In The Cultural Nature of Attachment: Contextualizing Relationships and Development; Keller, H., Bard, K.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Vicedo, M. Putting attachment in its place: Disciplinary and cultural contexts. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2017, 14, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sear, R. Beyond the nuclear family: An evolutionary perspective on parenting. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 7, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenkel, W.M.; Perkeybile, A.M.; Carter, C.S. The neurobiological causes and effects of alloparenting. Dev. Neurobiol. 2017, 77, 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morelli, G.A.; Chaudhary, N.; Gottlieb, A.; Keller, H.; Murray, M.; Quinn, N.; Rosabal-Coto, M.; Scheidecker, G.; Takada, A.; Vicedo, M. A pluralistic approach to attachment. In The Cultural Nature of Attachment: Contextualizing Relationships and Development; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Indigenous Services Canada. Reducing the Number of Indigenous Children in Care. Available online: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1541187352297/1541187392851 (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Crown and Indigenous Relations (CIR). Indigenous Peoples and Communities. 2020. Available online: https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1100100013785/1529102490303 (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Hamilton, S. Where Are the Children Buried? A Report for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. Available online: https://nctr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/AAA-Hamilton-cemetery-FInal.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Newland, B. Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative (Vol. 1); United States Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.bia.gov/sites/default/files/dup/inline-files/bsi_investigative_report_may_2022_508.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Hinge, G. Consolidation of Indian legislation, 1858–1975 (Vol. II); Department of Indian and Northern Affairs: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1985. Available online: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2017/aanc-inac/R5-158-2-1978-eng.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Fallon, B.; Lefebvre, R.; Trocmé, N.; Richard, K.; Hélie, S.; Montgomery, H.M.; Bennett, M.; Joh-Carnella, N.; Saint-Girons, M.; Filippelli, J.; et al. Denouncing the Continued Overrepresentation of First Nations Children in Canadian Child Welfare: Findings from the First Nations/Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2019; Assembly of First Nations: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, V.; Caldwell, J.; Pauls, L.; Fumaneri, P.R. A review of literature on the involvement of children from Indigenous communities in Anglo child welfare systems: 1973–2018. Int. Indig. Policy J. 2021, 12, 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Archives of Canada, Record Group 10, Vol. 6810, File 470-2-3, vol. 7, 55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3).

- Bryce, P. The Story of a National Crime: An Appeal for Justice to the Indians of Canada; James Hope; Sons Ltd.: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Indian Affairs Superintendent D.C. Scott to B.C. Indian Agent-General Major D. McKay, DIA Archives, RG 1-Series 12 April 1910.

- Choate, P.; CrazyBull, B.; Lindstrom, D.; Lindstrom, G. Where do we from here? Ongoing colonialism from Attachment Theory. Aotearoa N. Z. Soc. Work 2020, 32, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, P.W.; McKenzie, A. Psychometrics in Parenting Capacity Assessments—A problem for First Nations parents. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2015, 10, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, G.; Choate, P.; Bastien, L.; Weasel Traveller, A.; Breaker, S.; Breaker, C.; Good Striker, W.; Good Striker, E. Nistawatsimin: Exploring First Nations Parenting: A Literature Review and Expert Consultation with Blackfoot Elders; Mount Royal University: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2016; Available online: https://cwrp.ca/sites/default/files/publications/exploring_first_narions_parenting_a_literature_review_and_expert_consultation_with_blackfoot_elders.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2022).

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- United Nations. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (S.C. 2021, c. 14). Available online: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/U-2.2/page-1.html (accessed on 24 June 2022).

- Choate, P.; Lindstrom, G. Inappropriate application of Parenting Capacity Assessments in the child protection system. In Imaging Child Welf. Spirit Reconcil; Badry, D., Montgomery, H.M., Kikulwe, D., Bennett, M., Fuchs, D., Eds.; University of Regina Press: Regina, SK, Canada, 2018; pp. 93–115. [Google Scholar]

- Carriere, J.; Richardson, C. From longing to belonging: Attachment theory, connectedness, and indigenous children in Canada. In Passion for Action in Child and Family Services: Voices from the Prairies; McKay, S., Fuchs, D., Brown, I., Eds.; Canadian Plains Research Center: Regina, SK, Canada, 2009; pp. 49–67. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP). Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples; Commission: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Choate, P.; Lindstrom, G. Parenting Capacity Assessment as a Colonial strategy. Can. Fam. Law Q. 2017, 37, 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Neckoway, R.; Brownlee, K.; Castellan, B. Is attachment theory consistent with Aboriginal parenting realities? First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2007, 3, 65–74. Available online: https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/online-journal/vol3num2/Neckoway_Brownlee_Castellan_pp65.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Neckoway, R.; Brownlee, K.; Jourdain, L.W.; Miller, L. Rethinking the role of attachment theory in child welfare practice with Aboriginal people. Can. Soc. Work Rev. 2003, 20, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, H.; Bard, K.; Morelli, G.; Chaudhary, N.; Vicedo, M.; Rosabal-Coto, M.; Scheidecker, G.; Murrary, M.; Gottlleib, A. The myth of universal sensitive responsiveness: Comment on Mesman et al. Child Dev. 2017, 89, 1921–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keller, H.; Bard, K. The Cultural Nature of Attachment: Contextualizing Relationships and Development; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Forslund, T.; Granqvist, P.; van IJzendoorn, M.H.; Sagi-Schwartz, A.; Glaser, D.; Steele, M.; Hammarlund, M.; Schuengel, C.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Steele, H.; et al. Attachment goes to court: Child protection and custody issues. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2022, 24, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granqvist, P.; Sroufe, L.A.; Dozier, M.; Hesse, E.; Steele, M.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H.; Solomon, J.; Schuengel, C.; Fearon, R.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; et al. Disorganized attachment in infancy: A review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2017, 19, 534–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duschinsky, R. Cornerstone of Attachment Research; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Atwool, N. Attachment and resilience: Implications for children in care. Child Care Pract. 2006, 12, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskins, S.; Beeghly, M.; Bard, K.A.; Gernhardt, A.; Liu, C.H.; Teti, D.M.; Thompson, R.A.; Weisner, T.S.; Yovsi, R.D. Meaning and methods in the study and assessment of attachment. In The Cultural Nature of Attachment: Contextualizing Relationships and Development; Keller, H., Bard, K.A., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Bear Chief, R.; Choate, P.; Lindstrom, G. Reconsidering Maslow and the Hierarch of Needs from a First Nations perspective. Aotearoa N. Z. Soc. Work. 2022, in press.

- Amir, D.; McAuliffe, K. Cross-cultural, developmental psychology: Integrating approaches and key insights. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2020, 41, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sear, R.; Mace, R. Who keeps children alive? A review of the effects of kin on child survival. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2008, 29, 1–18. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.10.001 (accessed on 13 March 2022). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henrich, J. WEIRDest People World: How West Became Psychol. Peculiar Part. Prosperous; Farrar, Straus; Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Robertson, J. The psychological parent. Adopt. Fostering 1977, 87, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, J.; Freud, A.; Solnit, A.J. Beyond Best Interests Child; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1973/1979. [Google Scholar]

- Choate, P.; Bear Chief, R.; CrazyBull, B.; Lindstrom, D. The Journey of Care, Safety and Identity: Supporting Indigenous Children in Care; Mount Royal University: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2019; Unpublished monograph. [Google Scholar]

- Brown v. Canada (Attorney General) 2017 ONSC 251. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2017/2017onsc251/2017onsc251.html (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Nadeem, E.; Waterman, J.; Foster, J.; Paczkowski, E.; Belin, T.R.; Miranda, J. Long-term effects of pre-placement risk factors on children’s psychological symptoms and parenting stress among families adopting children from foster care. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2017, 25, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gypen, L.; Vanderfaeille, J.; De Maeyer, S.; Belenger, L.; Van Holen, F. Outcomes of children who grew up in foster care: Systematic review. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 76, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, J.M.; Beltran, S.J. Outcomes and experiences of foster care alumni in postsecondary education: A review of the literature. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 79, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, P.J.; Marcal, K.E.; Zhang, J.; Day, O.; Landsverk, J. Homelessness and aging out of foster care: A national comparison of child welfare-involved adolescents. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 77, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.J. Child Protection and Child Outcomes: Measuring the Effects of Foster Care. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007, 97, 1583–1610. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/30034577 (accessed on 10 June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Pecora, P.J.; Kessler, R.C.; O’Brien, K.; White, C.R.; Williams, J.; Hiripi, E.; English, D.; White, J.; Herrick, M.A. Educational and employment outcomes of adults formerly placed in foster care: Results from the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2006, 28, 1459–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, K.J.; Jackson, Y.; Noser, A.E.; Huffhines, L. Family Environment Characteristics and Mental Health Outcomes for Youth in Foster Care: Traditional and Group-Care Placements. J. Fam. Violence 2021, 36, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjern, A.; Vinnerljung, B.; Brannstrom, L. Outcomes in adulthood of adoption after long-term foster care: A sibling study. Dev. Child Welf. 2019, 1, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, N.; Xue, Y. Family first or the kindness of strangers? Foster care placements and adult outcomes. Labour Econ. 2020, 65, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, C. Inclusive foster care: How foster parents support cultural and relational connections for Indigenous children. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2020, 25, 585–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, P.; Kohler, T.; Cloete, F.; CrazyBull, B.; Lindstrom, D.; Tatoulis, P. Rethinking Racine v Woods from a Decolonizing Perspective: Challenging the Applicability of Attachment Theory to Indigenous Families Involved with Child Protection. Can. J. Law Soc. 2019, 34, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A.J.; Hill, N.E. Ethnic–Racial Socialization in the Family: A Decade’s Advance on Precursors and Outcomes. J. Marriage Fam. 2020, 82, 244–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Degener, C.J.; van Bergen, D.D.; Grietens, H.W. Being one, but not being the same: A dyadic comparative analysis on ethnic socialization in transcultural foster families in the Netherlands. Child Fam. Soc. Work 2022, 27, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaBrenz, C.A.; Kim, J.; Harris, M.S.; Crutchfield, J.; Choi, M.; Robinson, E.D.; Findley, E.; Ryan, S.D. Racial Matching in Foster Care Placements and Subsequent Placement Stability: A National Study. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine v. Woods. [1983] 2 S.C.R. 173. Available online: https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/2476/index.do (accessed on 4 May 2018).

- ZB (Re), 2022 ABPC 66. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abpc/doc/2022/2022abpc66/2022abpc66.html?resultIndex=8 (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- MU v Alberta (Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act, Director), 2022 ABPC 42. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abpc/doc/2022/2022abpc42/2022abpc42.html?searchUrlHash=AAAAAAAAAAEADVNDIDIwMTksIGMgMjQAAAABABAvNTY5MTktY3VycmVudC0xAQ&resultIndex=5 (accessed on 18 June 2022).

- SM v Alberta (Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act, Director), 2019 ABQB 972. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abqb/doc/2019/2019abqb972/2019abqb972.html?autocompleteStr=SM%20v%20Alberta%20&autocompletePos=1 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- URM (Re) 2018 ABPC 96. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abpc/doc/2018/2018abpc96/2018abpc96.html?resultIndex=1 (accessed on 31 August 2019).

- D.P. v. Alberta (Child, Youth and Family Enhancement Act, Director), 2016 ABPC 212. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/en/ab/abpc/doc/2016/2016abpc212/2016abpc212.html?resultIndex=1 (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Degener, C.J.; van Bergen, D.D.; Grietens, H.W. The ethnic identity of transracially placed foster children with an ethnic minority background: A systematic literature review. Child. Soc. 2022, 36, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, E. Fostering cultural development: Foster parents’ perspectives. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2011, 33, 2230–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sinclair, R. Identity lost and found: Lessons from the sixties scoop. First Peoples Child Fam. Rev. 2007, 3, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S.; Crey, E. Stolen from Our Embrace: The Abduction of First Nations Children and the Restoration of Aboriginal Communities; Douglas McIntyre Ltd.: Hagen, Germany, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- White, S.; Gibson, M.; Wastell, D.; Walsh, P. Reassessing Attachment Theory in Child Welfare; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, E. Review of: Reassessing attachment theory in child welfare. Aotearoa N. Z. Soc. Work. 2021, 33, 116–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boatswain-Kyte, A.; Trocmé, N.; Esposito, T.; Fast, E. Child protection agencies collaborating with grass-root community organizations: Partnership or tokenism? J. Public Child Welf. 2022, 16, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choate, P.; Tortorelli, C. Attachment Theory: A Barrier for Indigenous Children Involved with Child Protection. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148754

Choate P, Tortorelli C. Attachment Theory: A Barrier for Indigenous Children Involved with Child Protection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(14):8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148754

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoate, Peter, and Christina Tortorelli. 2022. "Attachment Theory: A Barrier for Indigenous Children Involved with Child Protection" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 14: 8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148754

APA StyleChoate, P., & Tortorelli, C. (2022). Attachment Theory: A Barrier for Indigenous Children Involved with Child Protection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8754. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148754