The Role of Spirituality during Suicide Bereavement: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Approval

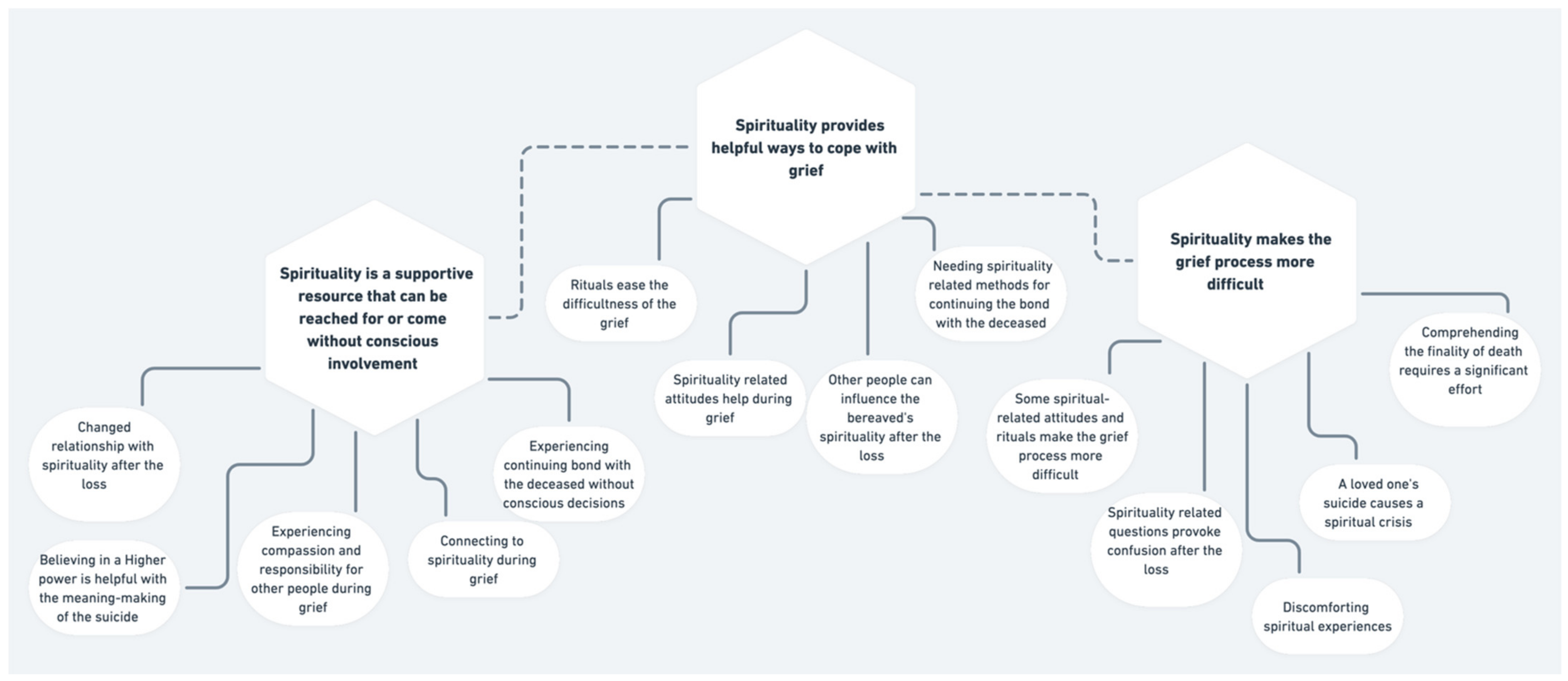

3. Results

3.1. Spirituality Is a Supportive Resource That Can Be Reached for or Come without Conscious Involvement

3.1.1. Changed Relationship with Spirituality after the Loss

My service is like this, prayer service, during glorification, when I have to pray with my community, and ask the spirit, what the spirit says not just to me personally, but to the community, then the prayers too are strong and they just come and you don’t need to translate the scripture, words from the scripture just come to consciousness and then I say them, translate them to people who are near me and for me… I make sure that God is talking to me, I don’t remember anything by heart, but I just read, and God gives me strength to remember exact things that he wants me to say.(Agnė, 36)

I don’t know, I just turned, and some force pushed me into the child’s room. And I go into the room, turn to the left and he was just there on the wardrobe.(Asta, 36)

To have those base virtues and comply with them. Like I said, I never blamed anyone for this situation (for husband’s death), didn’t blame. hh the one everyone attacked (blamed for the husband’s suicide).(Elena, 34)

But like I said, we concentrate on the negative things and can’t see anything else. And here is where Lithuanians seem genuine. Some of course I met horribly. I am also saying this as a Russian and it doesn’t depend on nationality, it’s just about the person… So now I understand that all of us, we are all the same, absolutely the same. And I felt amazing, even if I say that there are humanely humans, that it still exists.(Asta, 36)

But you know, when a year passed, then I felt that I am strong. And I stopped getting mad about their comments. I felt that no matter how hard it is, I manage the kids well.(Rasa, 41)

When you start to become aware, create a better world, to do something, then it doesn’t have any meaning. And somehow like I said that understanding, it came, and there is no point to it, you just must experience it and spirituality is part of the experience—to not harm another, not harm nature, to create, to leave something better when your gone, it doesn’t have to be visible, and people forget really fast, really fast. It’s an existential, like you’re nothing.(Nida, 35)

I feel like a giant comparing my spirituality five years back. Because there is a different quality, a completely different level of faith, communication with God and the work with community, worship. It’s like God says, I will give you an abundant life, and now I have that abundance. Abundance, the fulfillment, in any way, I have everything.(Agnė, 36)

And throughout the mourning, during the funeral, I felt as if I was being carried on arms, I don’t know how to say it, I actually felt, that I was being carried by God, and I couldn’t by myself, I saw his mom, and his mom was hysterical, going crazy, and she suffered terribly, and there was a lot of guilt there, childhood did its own thing, i understand, that feeling of guilt, but I also saw what kind of pain one can feel if they don’t believe in God, when the person is alone in that pain, he is alone and he doesn’t have anyone to call upon, he doesn’t have anyone to rely on, like it says in the psalms, if thousands fall from the right and thousands from the left, you will be untouched and I felt like the world had fallen, it was falling, and I was left with two small kids, I didn’t have a job, but I felt, that I am in God’s hands, in his embrace and I never felt guilt, I was just sad, really sad, and I understood his pain.(Agnė, 36)

3.1.2. Believing in a Higher Power Is Helpful with the Meaning-Making of the Suicide

And another thing that supported me, well supported, I unconsciously knew that someday it will happen. Even though you don’t think about it. Because like I said, since I’m interest in esotericism, I was in regression some time ago. In a regression seminar. That you can go back, go to the future. It’s a conscious dream. And that was seventeen years ago. A long time ago. And then I dreamed about a different country, where my future husband works, town, all their buildings, I remember how I explored it. I dreamed about myself with kids in mourning clothes. I was wearing a black dress and the three of us with kids, the husband wasn’t with us. And then I cried, o God, how I cried. I’ve never cried as much as I did then.(Jurga, 49)

There was suicide in his family, his grandfather ended up under the tracks, or something, it looks like that, whoever believes in those things. I think it’s of the same matter and maybe he finished it in his family.(Laima, 28)

I absolutely saw I mean that we have a situation and now looking back, we had a situation with the ghost of the dead and when the exorcist prayed for him and asked him, where do you feel in the body, some sort of sensation right, they make conclusion according to that, diagnosis and he said in the spine.(Agnė, 36)

It looks like maybe he (God) wanted to make me stronger and that I would be ready for my current life.(Asta, 36)

In the end he talked more about God and believed in him, and he talked about the last judgement day or something, about a refinery. That’s why he also encouraged me and somehow, he was slowly taking control, I mean, to not do anything bad. Because I thought maybe that he was sorry or not sorry, but I just think: “well yeah, however much it hurts me, but he doesn’t have any problems there (in the afterlife).”(Rasa, 41)

3.1.3. Experiencing Compassion and Responsibility for Other People during Grief

It was really difficult at first, but it’s like I said two little kids and it’s not okay. You have someone to take them, you can’t just put them aside, you must stand up, stand tall and move forward. So in this case my focus is on the first days.(Elena, 34)

The journey continues even now slowly, like the muscles, the spiritual ones, they are stronger now, the first step shows this, that I want to do that group (self-help group) so I believe that this is a sign that if I can help others, that it’s a sort of healing process. If that energy, when I start to move and I’m ready to share with others, the balance is being restored.(Liepa, 49)

Right after the loss, I received one questionnaire, then another, and my mom said stop, let it go, why do you need this, to reopen the wound, she said, don’t you understand, I rethink the event over and over and over again, and a thousand times more, and I said it’s not getting any better, and… if I’m doing a good job by sharing my thoughts, if they are worthy or not, but I say, maybe it’ll help someone, maybe someone will see that moment, when it happens.(Dalia, 62)

3.1.4. Connecting to Spirituality during Grief

I never knew how to pray, because it always seemed, that there are some kind of rules, how you should address… If it’s God, or the earth, or what you believe and somehow I thought I’m not doing it right and then I asked my grandmother, so how should I pray now, in your own words, how you want to, that’s how you should pray, you’ll be heard anyway, or so I would say a worldly prayer, the one for the dead of course, because I thought, that it is necessary. And then in my own words I’d just pray, I actually would just ask, not pray, that I wouldn’t go crazy, that I’d be given strength, to be here, but I prayed to him. Yeah. For an easy path, I prayed for his forgiveness, somehow my prayer was related to his easy departure.(Laima, 28)

And that is why, why I say that it would happened in church. I would want to kneel, to lean on those wooden things, to lay my head and cry. And somehow that atmosphere would provoke that reaction, those organs, when they play. And the priests’ sermons, it always seemed that it was talking about me, or about him, or about our family. Somehow everything seems to be happening at the right time and place.(Rasa, 41)

It has a special effect on me even now, mass and the sacral music, singing, it’s unbelievable, maybe it’s even painful, the music. I always, it tears me up.(Laima, 28)

3.1.5. Experiencing Continuing Bond with the Deceased without Conscious Decisions

Later I was going to work, a few years after his death, I was sleeping, and with his knee to my side boom boom near the bed, get up, boom boom, get up, I look aaaa it’s 8, I overslept, that means before I opened the store, at that moment and my subconscious connected my alarm, that I need to go to sleep, but I thought that I felt him, that he is waking me up, that honey, wake up, go to work, was him, and I don’t know how to say it, I just felt that substance. It seems that the air is denser and if you turned on the light you’d see that it’s him in layers, like turning the light on in a fog, this way and that way, and when you catch this fog with a flashlight, from one corner it is clear, but from another you see the layers, it’s an impression, or it’s my experience talking, if it’s real, I want to believe it, that it can actually happen.(Dalia, 62)

And I dreamed that he… As if there was a party and he came a bit drunk, but he was in a good mood, happy. The only thing is that he didn’t come near me. His brother was there. And he went up to his brother to talk and I hear what he is speaking. And he was interacting with him in a brotherly way, in a manly way. And he tells him: “you know why I love my life? Because, however much money I spend, there will always be more. Whenever I come back home, nobody is mad at me and (starts crying) whatever sins I commit, He always forgives me. And “he” as I understand, was Jesus, I knew that very clearly for some reason, that he was in His care, in that other life. And there is eternal joy, and he doesn’t have any problems there… It affected me deeply, it was very strong, because… You know some dreams are very vivid, others not so much… but that dream, it’s like I said, it seems I see it clearly, word for word. And somehow, I felt that … you know this was after, wait after, after five months, or four months after his death, that type of dream. So I don’t know, it seems to me, that was the first, clearly some connection from him.(Rasa, 41)

3.2. Spirituality Provides Helpful Ways to Cope with Grief

3.2.1. Rituals to Ease the Difficulty of the Grief

People were lost after a sudden death. They experience it the same, they are in a period of shock. Then they, if they continue the burial service, all those things and have the energy to do all of that. But usually, they don’t want to be alone, they want to take care of everything.(Karolina, 46)

But I said right away (giggles)… find me the best hall, the best place. I will pay whatever you want, but I want the best… There were no questions because he was also always the one to choose the best. Or choosing closest to the best. Money was spent so that it’d be nice. I knew that people would come, and you need to, so that the funeral would be, how to say so that he would truly be respected.(Jurga, 49)

What I understood, when his casket was being buried, I actually understood that he is not here, that this is a body, I thought of this often.(Agnė, 36)

So those journeys and world knowledge and new knowledge of nature, that you climb the mountain, it means those special paths right, and you get to the top and there is this huge wind, and you can’t think of anything else and it’s a new place for you and a place you can’t find in Lithuania, you start to think about the world differently, new colors appear. You understand that… there is more of everything and it’s different from what you’re used to. Or when you stand up, on salt, the lake of salt right where it is white and there is no horizon, and you are in the middle of nowhere. You just hang in the middle and you understand that there is something… Something magical.(Nida, 35);

My nature is creative, and I am creative, so I searched through drawing and my hobby allowed me to find that, what I did in my childhood, I drew a lot, was picky, sewed and still I came back to that after the funeral, I found wool, I found wool and looked at the process in a more creative way.(Liepa, 49)

In that hour and a half when you do yoga, you just, translate stress, anxiety, tension, thoughts through the body, because when you do it, you don’t think about other things, you just think how to do yoga. How to bend your legs, how to bend your body and other stuff. And in the end, there is shavasana, where you just lay ten minutes, it’s called the dead pose. You must disconnect and not think of anything. So, this is the best thing, when you lay down, open your body, and not see or hear anything anymore. That is equal to meditation actually. And yeah. This thing was taught by the teacher and told us that when you come to yoga it’s like a new page, you forget everything that is around you, and start from scratch. Actually, that helps a lot.(Jurga, 49)

Just after my husband’s death I had space, usually during my talks with my psychologist. And you know that once a week you will complete that exercise either way… I tried to and each evening, right before going to sleep to think about the day… with completed facts, put into drawers and not worry about things, that are out of your control.(Elena, 34)

There are people, I started to move from household stuff to people, God and those people exist, and I have a job and friends and my relatives don’t turn from me and then everything expands, I have so much and to be grateful, and then joy comes from gratitude and then I understood, I concentrate on what I don’t have. And that is a huge problem. And when I started to focus on what I do have, how much there is and health, and that my kids are healthy and that is amazing.(Agnė, 36)

And when we talked about fire, then I just wanted to burn something. Because Rimas (the deceased) wanted to be cremated. So, fire, even to him, seemed to cleanse and that it will somehow show all those bad things and fire is powerful, that it just burns (whispers) just burns.(Eglė, 31)

This is about being religious, or how to say it, but I know now how much it snowed, how much it winded… but I walk there… and my knee joint is week, I have a hard time walking, fifty meters is a lot… I must go to church… so I had to walk a kilometer and three hundred meters.(Dalia, 62)

3.2.2. Spirituality Related Attitudes Help during Grief

How to say… I’m a believer in energy and energetic bodies. I’m not sorry when someone dies and I usually don’t cry, because I know that around our body… I can feel other bodies and that consciousness is not in the body, but it’s… you can expand your consciousness to eternity.(Eglė, 31)

As for spirituality, in the sense of religion, I discovered specific philosophical points in Buddhism. Through literature, I started to read more books that helped me… I found that the whole theory of mindfulness came from Buddhist philosophy… The simplicity of philosophy and the simplicity of being has helped me restore that spiritual balance… I am suffering because I wanted everything. It is that desire to have a person, the desire to be attached… the desire to control that situation… Well, it does not happen that way. This understanding of mind through mindfulness… and all these fundamental truths and points of reference in Buddhism may have helped restore that spiritual balance little by little… some kind of mantra, as some kind of reminder that no one has promised you anything.(Nida, 35)

What more to hang on to? Some kind of will of God that God knows what he is doing. To trust Him and His plan. Maybe it is awful for me now, it is hard, but apparently, for some reason, it must be that way.(Rasa, 41)

3.2.3. Other People Can Influence the Bereaved’s Spirituality after Loss

The possibility of getting some information to reach or go on that kind of spiritual path… we do not have such very easily accessible information… like could you help me here now, if not for some kind of psychological help, but let’s say something like that.(Karolina, 46)

Like even psychologists cannot share advice. They must force a person to choose some solution. I received honest, real help (from the clergy) when I was told to thank the Lord. I was angry at first for such advice… However, I tried to practice what he told me, what was being advised to me, and it worked, and it actually worked.(Agnė, 36)

The cremation itself and saying goodbye before an essential aspect I talked about to my psychologist… That here is the fact of death. Well, that is why… the funerals usually are for the comprehending that it will not be like that anymore, that the husband will not be here anymore.(Elena, 34)

We have been with him so far. We have become like a family. We do not… discuss all those religious issues and so on. He is so humanly, so secular. Without those, you know, those constant sermons… He says: why are you torturing yourself… he (the husband) has chosen such a path, an easy path because it is much harder to fix problems than to die… he left you with the child, with your problems… You would be guilty if, say, you would hold him by the hands… and put his head in a loop, tighten it and push the chair… to the side, then you might be guilty of his death. And he did it himself, he decided so, he got into the loop, he was still so romantic, he says: with the music, he went away… And I would think so, but seriously, I did not throw him in that loop.(Asta, 36)

He noticed me, and he said… you must worry about yourself. There has been where people just from that high tension are getting problems… He apparently saw that already… I am already disappearing because my weight and everything… I was talking there, I did not even see anything, but I already had those somatic problems… And the priest drove me to the Crisis Centre. Nobody would help, only him.(Liepa, 49)

This bishop goes… And he talks to parishioners… I say I do not know how to approach you, but my husband hanged himself… So, he will never get forgiveness?… He took my hand, held it, and said, we are all invited to this earth… No religion appreciates suicide… it can be a condemnation for seven generations, like a cross, a sin… However, if at that moment when you do this… I even cannot say the word ‘suicide’… When you do this, some button is on, I believe, that at that moment there is like a trance, darkness, you are not able to think anything else.(Dalia, 62)

I do not know what I would do if not for my friends. Four friends of him came to the funeral and three hundred friends of mine, who supported me… I do not remember, but there were rows. Moreover, they gathered for me 10,000 euros during the funeral.(Asta, 36)

I see that he (the Muslim friend) understands that this is terrible and hurtful, but he believes in the afterlife…, and he thinks that everything is in God’s hands, nothing happens without reason, we met not without reason… He never criticized my views, he is interested in how I see the world, and I am interested in how he sees the world.(Nida, 35)

I met this nurse… believe it or not, she says, “I do not know, to say or not to say”… She says, I dreamt (the deceased husband)… I knew him… I stand there, and he sees me and goes to me, goes goes goes, says, how great is this, that I met you… You can pass over to (the bereaved woman), that the reason, why it happened… is that I killed a person in a car accident, I hid it, and I could not live with it… The first thought to me, because he hid so much from me… This could have been true.(Liepa, 49)

3.2.4. Needing Spirituality-Related Methods to Continue the Bond with the Deceased

I need some kind of process, some kind of ritual, which would help me understand and accept. So, I drove to his grave. Traditionally, I lit a candle.(Eglė, 31)

When I am in a city, I always go to the church, light a candle, because the candle is somehow cleansing… lifting his soul… it was always important to me that it would be easier for him, I lit the candles… so he would travel somewhere through the more straightforward path than it was for him here.(Laima, 28)

And his grave… I did not want a common grave. He was a wild person, and I made the grave like this. I planted perennial flowers, which can grow by themselves how they want.(Agnė, 36)

During the funeral I said to everyone, go out and give me half an hour to be with him alone… I lay near him, on the coffin and talked to him… Why did you do that, and for what?(Asta, 36)

At first, the conversations with him were casual… Now they are… when it is hard for me, for example, I talk to him, ask for help… I feel that he sees me all the time, my good and bad behaviors, he does not judge me, but he understands me… he is my angel, and when I pray, I always pray for him that he would care for my child and me.(Laima, 28)

3.3. Spirituality Makes the Grief Process More Difficult

3.3.1. Some Spiritual-Related Attitudes and Rituals Make the Grief Process More Difficult

I do not know if I could talk to the priest, it would be hard for me… Although, it would be interesting to find out his views towards people who died by suicide… what do they think, is it a big sin… My father said that for a priest, it is a sin not to live, to go away voluntarily… That is why I was afraid that he would talk badly about my fiancé… I did not want that.(Laima, 28)

Strangely, everyone would say, “do not cry because you are holding him here. You are not allowing him to go away… Nevertheless, I still cry. It’s cleansing for me… It eases me, but I am holding him here because of my tears… If you cry, his soul is drowning.(Laima, 28)

There were many opinions from the women, who are standardly religious… That God sends for people that much that they can carry… Yeah… I say, ok, what else can I carry? (Laughing ironically).(Elena, 34)

I heard from everybody on my first birthday without my husband… Many of them said that “not everybody is that strong” and congratulated me that they wanted to be as strong as me… I thought about it later, how people see the strength… that you don’t cry, smile, care for the children and move further… But a lot can happen. You just find the space for your emotions… It doesn’t mean that you don’t have them.(Elena, 34)

There were many attacks… for example, somebody brought the book of angels… I sat through this session and thought, what a moment… She (the spiritual leader) told me to do a break, pause, and use something… And then she went, and I sent here the sign of a pause in music… My healthy mind turned on… And I sent it (laughing) and didn’t talk to her anymore… It’s strange that she would want to include me into something and then powder everything, that I am not hurting, because… I AM HURTING… Why should I deny it?(Liepa, 49)

When I started to walk a spiritual path, I understood that any connection to the deceased is idolatry and witchcraft. I don’t understand our festivities, vėlinės (a traditional Lithuanian celebration for the souls of the dead). I don’t go to his grave, don’t light the candles.(Agnė, 36)

You know how the season has its perfume. Autumn, the scent of autumn and flowers, lilies. It seemed to me that the death happened again somewhere… My new husband gave me flowers as a gift and those lilies, I went inside my home and… the smell of death, the associations… death and corps, disgusting, even candles, you know, when they stand around the body, and the heat causes the smell of the dead body.(Laima, 28)

That sitting and watching the dead body is torturing for me, I don’t know, it is like, let’s torture ourselves now and watch the deceased person. To say goodbye is ok, but you need 15 min for that.(Liepa, 49)

I am determined to follow the trends (of the funeral) because it’s unnecessary for me. It is meaningless to me. On another side, we did it all for the parents. Because they are from an older generation, it was, wow, how important for them.(Jurga, 49)

And all those stories about graves and tombstones, and this comparison with other monuments, which are more interesting… Maybe if it would… not be Catholicism, but Protestantism… maybe there would be fewer problems, they like simplicity.(Nida, 35)

It was a problem for me where to leave my child with disabilities because nobody knew how to feed him… Children should not be near the coffin… But not everybody has people who could watch them.(Asta, 36)

Nobody listened to his wish to be cremated because the family was furious and blamed me… The funeral was tragic… It was very hard for me, and his relatives didn’t allow me to his coffin, said terrible things to me…(Eglė, 31)

The unpreparedness of the priest, inability to sympathize, comfort, comment about stuff that we all go through the same stages of life, everybody dies, and it’s a challenge… During the funeral or a month after…, he chooses the text from the Bible about how Jesus heals sick people and raises the dead. He accentuates the text several times, especially the point about blindness. But he should know that the blindness in the Bible is not actual blindness… So, what he wanted to say about my husband was that he had this physical disability, but it doesn’t mean that he was spiritually blind… You must search for metaphors in the Bible and not only cite the text and talk about it that the community member had a visual disability. I didn’t understand what he wanted to say.(Nida, 35)

You light a candle–they shout at you: “why did you light that candle?”. But it’s nice for me, it helps me. I wanted to light the candle at this place… It’s my spirituality and faith.(Eglė, 31)

3.3.2. Spirituality Related Questions Provoke Confusion after the Loss

It’s sad–you don’t want to eat, to get up… I don’t want to do anything, I don’t have what to give to others, and my energy level is too low. I am on a line of exhaustion. And then the questions came: if I don’t have what to give and no energy to live, is it worth it to torment myself and live…? It is the most challenging moment.(Eglė, 31)

Why, what, why for me, not for someone else? I didn’t do anything wrong in life. And you start to reconsider your whole life, how, how, how. Maybe you did something to somebody. And of course, people come who “help” you find it.(Asta, 36)

And I was sorry before that was guilt because I was angry about many things, mad about him when he was still alive, that these letters from the bank, his debts… I am still mad… And others ask, why did it happen? And I say to them, just because, I don’t know why.(Liepa, 49)

You know how you go from one extreme to another… you start to blame God, that he is terrible and how could he let it… you start to pray… then start to hate everybody, God doesn’t exist, every human is awful… Then you begin to love everybody. Then you start to hate everybody because you need help but don’t know what helps, and you are mad at people who can’t help you.(Asta, 36)

3.3.3. A Loved One’s Suicide Causes a Spiritual Crisis

This cancer of the soul eats you from inside. It spiritually kills you… You don’t want anything; you don’t believe in anything… I called myself a mass then. The mass, which doesn’t think, is languid. And to gather this mass inside, you need a lot of effort… A lot of self-reflection.(Asta, 36)

And you know, we agreed nicely to each other, cherished one another, and then you feel abandoned, betrayed… that he left me.(Asta, 36)

I would not want that my daughter would know what suicide is. That there would not be such a concept–to kill. Who tells the people that they can kill themselves?… I disagree with that.(Eglė, 31)

There was one more sign before… I wanted to volunteer at a suicide helpline… I wanted to go to the courses… I went through. And in the end, there is like an exam… And I didn’t pass this exam… Later I understood that I would not be able to withstand this topic. All the depression, children. These hurtful topics, only during the courses do I comprehend that it is seriously hard… Later I thought that… the life led me to this helpline, that I would know more about depression, but I gave up. I didn’t understand that I needed this.(Jurga, 49)

In the church, there is a mass paid for. And the priest doesn’t hesitate to take the money for the mention of the deceased…, and he also decides to congratulate a birthday person. On the same mass… And when you stand in the first row, there is a candle in front of you… And the choir sings “happy birthday” I just want to take the candle holder and throw it into that priest… Because it is a complete disrespect to people, their grief… I started not to believe in religion, especially in Christian people.(Nida, 35);

There is this anger if God exists, why is he doing that. Why do others live without any losses? Everything is good for them… And for me, punch after punch… When will it end? Or why? I say to God, why do you do that? Do you want to kill me? I don’t have the strength anymore.(Asta, 36);

We soaked in existentialism together (with the deceased husband). Heidegger and all other saints, I used to say to him… And I started to think that it was too narrow for me… I said to him, there are many other thinkers, other thoughts, and perspectives on life, not only existentialism… It is too narrow… It can’t save me.(Agnė, 36)

3.3.4. Comprehending the Finality of Death Requires Significant Effort

I don’t have the answer about the afterlife. I would like to believe that it exists, but I have doubts about it.(Rasa, 41)

I dreamt of the decaying body… I think about it, how that body looks now under this clayey earth?(Nida, 35)

There were moments when you spend time with children and catch yourself thinking, how nice it would be if he would be here… If I start to notice myself in these illusions, dreams, where is the person… I would go to the grave. To put it into my head, this is the reality, not what you are thinking about.(Elena, 34)

The bond is through memories… What we did, how we communicated, talked, but I don’t believe that he… watches me from Heaven… I don’t know his state if he is sleeping, how the Jews say, Sheol, the afterlife, where they wait for resurrection… I don’t raise these questions for myself. I live my life with the living.(Agnė, 36)

When he appears in dreams, it unnerves me… We were harmonized when we lived together. I just would comply, not listen… But now I see that two years went by… And I don’t want to comply with him anymore, even in the dream. It’s better that I would take him and push him aside… I don’t need it. I will manage by myself… If you went away, live your life on your own.(Jurga, 49)

If you are nearby… you will constantly be with various emotions… His mother goes to his grave every day. I think she harms herself. She takes her energy away from herself… Why fall together?(Eglė, 31)

3.3.5. Discomforting Spiritual Experiences

It was an all-surrounding, the death… I tried to explain it to my doctor, the paralyzing fear of dark powers, which is very terrifying… It seemed that I was going out of my mind, nobody could understand me, and I couldn’t explain what I feared. I saw something when I walked the dog… I worked at the time and before work at 7.30 a.m. In the morning, I had to walk my dog before work in winter. It was cruel, I went only on the streets, near the cars, but if I looked at the forest, it seemed that somebody was in the woods. I saw the hanging men in the woods.(Laima, 28)

One thing was tricky… the earth was frozen… I cremated him… And they say, we can’t dig, to bury the urn. So, it stood at my home for a couple days… It preyed on me cruelly. And my parents, grandma… they felt that he is nearby… They are not believers in ghosts or else… But they felt that he had walked in the house, only in the corridor, not the rooms… It was a hard feeling inside that he was not away. I didn’t comprehend that feeling.(Asta, 36)

And I dream about him, and he is angry. He is gloomy, he is a grim person, and he comes angry in my dreams. I scream at him, go away, and don’t disturb my life anymore… Several weeks ago. He annoyed me, slipping into my nights and days. And I say in my thoughts, go away… Help us, don’t annoy us. Why do you need to come here and be grim, regulate something… Give us peace. And then the spirit goes away… When the person dies his own death, it is not the same. When he raises his hand against himself, it is cruel. The soul flies around, I don’t know, for hundred years.(Jurga, 49)

4. Discussion

4.1. Spirituality Is a Supportive Resource That Can Be Reached for or Come without Conscious Involvement

4.2. Spirituality Provides Helpful Ways to Cope with Grief

4.3. Spirituality Makes the Grief Process More Difficult

4.4. Practical Implications

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO (World Health Organization). Suicide; World Health Organization Media Centre: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/publications/world-health-statistics (accessed on 12 July 2022).

- Cerel, J.; Brown, M.M.; Maple, M.; Singleton, M.; Van de Venne, J.; Moore, M.; Flaherty, C. How Many People Are Exposed to Suicide? Not Six. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2018, 49, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellini, S.; Erbuto, D.; Andriessen, K.; Milelli, M.; Innamorati, M.; Lester, D.; Sampogna, G.; Fiorillo, A.; Pompili, M. Depression, hopelessness, and complicated grief in survivors of suicide. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Erlangsen, A.; Runeson, B.; Bolton, J.M.; Wilcox, H.C.; Forman, J.L.; Krogh, J.; Shear, K.; Nordentoft, M.; Conwell, Y. Association between spousal suicide and mental, physical, and social health outcomes: A longitudinal and nationwide register-based study. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriessen, K.; Krysinska, K.; Hill, N.T.M.; Reifels, L.; Robinson, J.; Reavley, N.; Pirkis, J. Effectiveness of interventions for people bereaved through suicide: A systematic review of controlled studies of grief, psychosocial and suicide-related outcomes. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Castelli Dransart, D.A. Spiritual and religious issues in the aftermath of suicide. Religions 2018, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gall, T.L.; Henneberry, J.; Eyre, M. Spiritual beliefs and meaning-making within the context of suicide bereavement. J. Study Spiritual. 2015, 5, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čepulienė, A.A.; Pučinskaitė, B.; Spangelytė, K.; Skruibis, P.; Gailienė, D. Spirituality and religiosity during suicide bereavement: A qualitative systematic review. Religions 2021, 12, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G. Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: A review. Can. J. Psychiatry 2009, 54, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hornborg, A.C. Are We All Spiritual? A Comparative Perspective on the Appropriation of a New Concept of Spirituality. J. Study Spiritual. 2011, 1, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacey, D. The Spirituality Revolution: The Emergence of Contemporary Spirituality; Brunner-Routledge/Tailor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zinnbauer, B.J.; Pargament, K.I.; Scott, A.B. The emerging meanings of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. J. Pers. 1999, 67, 889–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.I. Spiritually Integrated Psychotherapy: Understanding and Addressing the Sacred; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, T. Spirituality with and without religion—Differential relationships with personality. Arch. Psychol. Relig. 2012, 34, 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atkins, P.; Schubert, E. Are spiritual experiences through music seen as intrinsic or extrinsic? Religions 2014, 5, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koenig, H.G. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012, 2012, 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pargament, K.I.; Lomax, J.W. Understanding and addressing religion among people with mental illness. World J. Psychiatry 2013, 12, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jastrzębski, A.K. The challenging task of defining spirituality. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 2022, 24, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Franz, M.L. The Process of Individuation. In Man and His Symbols; Jung, C.G., Ed.; Ancor Press: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 158–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kast, V. Time to Mourn: Growing through the Grief Process; Daimon Verlag: Einsiedeln, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Krysinska, K.; Jahn, D.R.; Spencer-Thomas, S.; Andriessen, K. The Roles of Religion and Spirituality in Suicide Bereavement and Postvention. In Postvention in Action: The International Handbook of Suicide Bereavement Support, 1st ed.; Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Onja, T.G., Eds.; Hogrefe: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 186–197. [Google Scholar]

- Jahn, D.; Spencer-Thomas, S. Continuing bonds through after-death spiritual experiences in individuals bereaved by suicide. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 2014, 16, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, D.; Spencer-Thomas, S. A qualitative examination of continuing bonds through spiritual experiences in individuals bereaved by suicide. Religions 2018, 9, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stelzer, E.M.; Palitsky, R.; Hernandez, E.N.; Ramirez, E.G.; O’Connor, M.F. The role of personal and communal religiosity in the context of bereavement. J. Prev. Interv. Community 2020, 48, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecreek, L.; Mottram, K. The Religious Life during Suicide Bereavement: A Description. Death Stud. 2009, 33, 741–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.R. Is Suicide Bereavement Different? A Reassessment of the Literature. Suicide Life Threat. Behav. 2001, 31, 91–102. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1521/suli.31.1.91.21310?casa_token=mCuuR7SbKIAAAAA:wVS8peEcnM_hGIqSL1J2wA21tGlQEluDR083Tku6DCpDZt8sZ4youqpu9qYWqH9GzSJcnMy6LsG (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Jordan, J.R. Postvention is prevention—The case for suicide postvention. Death Stud. 2017, 41, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.; Xander, C.J.; Blum, H.E.; Lutterbach, J.; Momm, F.; Gysels, M.; Higginson, I.J. Do religious or spiritual beliefs influence bereavement? A systematic review. Palliat. Med. 2007, 21, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, A.H.; Currin-McCulloch, J.; Franklin, C.; Cole, A.H., Jr. Spirituality/religiosity’s influence on college students’ adjustment to bereavement: A systematic review. Death Stud. 2018, 42, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichtenthal, W.G.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Currier, J.M.; Roberts, K.; Jordan, N. Cause of Death and the Quest for Meaning after the Loss of a Child. Death Stud. 2013, 37, 311–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pargament, K.I.; Smith, B.W.; Koenig, H.G.; Perez, L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1998, 37, 710–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargament, K.; Feuille, M.; Burdzy, D. The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions 2011, 2, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feigelman, W.; Jordan, J.R.; Gorman, B.S. Personal growth after a suicide loss: Cross-sectional findings suggest growth after loss may be associated with better mental health among survivors. OMEGA 2009, 59, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, S.A.; Johnson, L.C. Finding Meaning in a Child’s Violent Death: A Five-Year Prospective Analysis of Parents’ Personal Narratives and Empirical Data. Death Stud. 2003, 27, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrocinque, J.M.; Hartwell, T.; Metzger, J.W.; Carapella-Johnson, R.; Navratil, P.K.; Cerulli, C. Spirituality and religion after homicide and suicide: Families and friends tell their stories. Homicide Stud. 2020, 24, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, O.C. Sampling in Interview-Based Qualitative Research: A Theoretical and Practical Guide. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2014, 11, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddon, L.; Barry, J. Perspectives in Male Psychology: An Introduction; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J.M.; Vasey, P.L.; Diamond, L.M.; Breedlove, S.M.; Vilain, E.; Epprecht, M. Sexual orientation, controversy, and science. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 17, 45–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, A.M.; Kim, Y.; Prigerson, H.G.; Mortimer-Stephens, M. Complicated grief in survivors of suicide. Crisis 2004, 25, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Groot, M.; Kollen, B.J. Course of bereavement over 8–10 years in first degree relatives and spouses of people who committed suicide: Longitudinal community based cohort study. BMJ 2013, 347, f5519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McIntosh, J.L.; Wrobleski, A. Grief reactions among suicide survivors: An exploratory comparison of relationships. Death Stud. 1988, 12, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farberow, N.L.; Gallagher-Thompson, D.; Gilewski, M.; Thompson, L. Changes in grief and mental health of bereaved spouses of older suicides. J. Gerontol. 1992, 47, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlatte, O.; Oliffe, J.L.; Salway, T.; Knight, R. Stigma in the bereavement experiences of gay men who have lost a partner to suicide. Cult. Health Sex. 2019, 21, 1273–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agerbo, E. Midlife suicide risk, partner’s psychiatric illness, spouse and child bereavement by suicide or other modes of death: A gender specific study. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 407–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caine, E.D. Does spousal suicide have a measurable adverse effect on the surviving partner? JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 443–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, L.M.; Wong-Wylie, G.; Rempel, G.R.; Cook, K. Expanding Qualitative Research Interviewing Strategies: Zoom Video Communications. Quality 2020, 25, 1292–1301. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/expanding-qualitative-research-interviewing/docview/2405672296/se-2 (accessed on 16. June 2022). [CrossRef]

- Krouwel, M.; Jolly, K.; Greenfield, S. Comparing Skype (video calling) and in-person qualitative interview modes in a study of people with irritable bowel syndrome—An exploratory comparative analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenner, B.M.; Myers, K.C. Intimacy, rapport, and exceptional disclosure: A comparison of in-person and mediated interview contexts. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2019, 22, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čepulienė, A.A. Silence and sounds: An autoethnography of searching for spirituality during suicide bereavement in life and research. Religions 2022, 13, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, B.E.; Witkop, C.T.; Varpio, L. How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2019, 8, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Teaching Thematic Analysis: Overcoming Challenges and Developing Strategies for Effective Learning. Psychologist 2013, 26, 2. Available online: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/preview/937606/Teaching%20 (accessed on 9 May 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS.ti. Qualitative Data Analysis; Web. ATLAS.ti Gmbh: Berlin, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann, J.H.; Park, C.L. Religion and spirituality in adjustment following bereavement: An integrative review. Death Stud. 2008, 32, 703–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parente, N.T.; Ramos, D.G. The influence of spiritual-religious coping on the quality of life of Brazilian parents who have lost a child by homicide, suicide, or accident. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 2020, 22, 216–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.A. Inner Work; Harper San Francisco: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, R.G.; Calhoun, L. Posttraumatic Growth: A New Perspective on Psychotraumatology. Psychiatr. Times 2004, 21, 58–60. Available online: https://www.bu.edu/wheelock/files/2018/05/Article-Tedeschi-and-Lawrence-Calhoun-Posttraumatic-Growth-2014.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Moore, M.M.; Cerel, J.; Jobes, D.A. Fruits of trauma? Posttraumatic growth among suicide-bereaved parents. Crisis 2005, 36, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.R.S.; Hunter, A.G.; Priolli, F.; Thornton, V.J. “Pray that I live to see another day”: Religious and spiritual coping with vulnerability to violent injury, violent death, and homicide bereavement among young Black men. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Darrell, A.; Pyszczynski, T. Terror management theory: Exploring the role of death in life. In Denying Death: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Terror Management Theory; Harvell, L.A., Nisbett, G.S., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A.; Joseph, S.; Nair, R.D. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of posttraumatic growth in adults bereaved by suicide. J. Loss Trauma 2011, 16, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Baldwin, S.A.; Gillies, J. Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Stud. 2006, 30, 715–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.L.; Halifax, R.J. Religion and spirituality in adjusting to bereavement: Grief as a burden, grief as a gift. In Grief and Bereavement in Contemporary Society; Neimeyer, R.A., Harris, D.L., Winokuer, H.R., Thornton, G., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2021; pp. 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoz-Efe, I.; Erdur-Baker, O.; Servaty-Seib, H. Death rituals, religious beliefs, and grief of Turkish women. Death Stud. 2018, 42, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitima-Verloop, H.B.; Mooren, T.T.M.; Boelen, B.A. Facilitating grief: An exploration of the function of funerals and rituals about grief reactions. Death Stud. 2021, 45, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Possick, C.; Buchbinder, E.; Etzion, L.; Yehoshua-Halevi, A.; Fishbein, S.; Nissim-Frankel, M. Reconstructing the loss: Hantzacha commemoration following the death of a spouse in a terror attack. J. Loss Trauma 2007, 12, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrutton, A.P. Grief, ritual and experiential knowledge: A philosophical perspective. In Continuing Bonds in Bereavement; Klass, D., Steffen, E.M., Eds.; Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Doehring, C. Searching for wholeness amidst traumatic grief: The role of spiritual practices that reveal compassion in embodied, relational, and transcendent ways. Pastor. Psychol. 2019, 68, 241–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaswamy, S.; Richardson, V.; Price, C.A. Investigating patterns of social support used by widowers during bereavement. JMS 2004, 13, 67–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, D. The Wounded Healer: Counter-Transference from a Jungian Perspective; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Colucci, E.; Martin, G. Religion and spirituality along the suicidal path. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2008, 38, 229–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano, P.; Pizzorno, E.; Pompili, M.; Serafini, G.; Amore, M. Conceptualizations of suicide through time and socio-economic factors: A historical mini-review. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 2018, 35, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gailienė, D. Why are suicides so widespread in Catholic Lithuania? Religions 2018, 9, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ališauskienė, M.; Samuilova, I. Modernizacija ir Religija Sovietinėje ir Posovietinėje Lietuvoje. (Modernization and Religion in Soviet and Post-Soviet Lithuania). Cult. Soc. J. Social. Res. 2011, 2, 67–81. Available online: https://etalpykla.lituanistikadb.lt/object/LT-LDB-0001:J.04~2011~1367180257082/J.04~2011~1367180257082.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Kopacz, M.S.; Silver, E.; Bossarte, R.M. A Position Article for Applying Spirituality to Suicide Prevention. J. Spiritual. Ment. Health 2014, 16, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nickname | Age | Deceased Was Her | The Method of Suicide | Age of the Deceased | Time Elapsed After Suicide | Years Spent Together with the Deceased | The Number of Children | Education | Religious Affiliation | Place of Living | How Was the Interview Conducted? | Interview Duration | How Was the Participant Reached? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rasa | 41 | Husband | Hanging | 44 | 2.2 | 20 | 3 | Higher | Catholic | Rural area | Videocall | 1:49 | Filled the questionnaire |

| Nida | 35 | Husband | Overdose and hanging | 32 | 4.9 | 8 | 0 | Higher | Not affiliated | City | Videocall | 1:58 | Filled the questionnaire |

| Liepa | 49 | Husband | Hanging | 44 | 5 | 26 | 2 | Professional | Catholic with a question mark | Town | Videocall | 1:36 | Filled the questionnaire |

| Laima | 28 | Fiancée | Hanging | 30 | 4.5 | 6 | 0 | Higher | Catholic | City | In person | 1:58 | Filled the questionnaire |

| Karolina | 46 | Husband | Hanging | 55 | 2 | 26 | 2 | Higher | Catholic | City | Videocall | 1:01 | Proactively called by researchers |

| Eglė | 31 | Romantic partner | Hanging | 34 | 2.4 | 1.5 | 0 | Professional | No affiliation | City | In person | 1:43 | Proactively called by researchers |

| Elena | 34 | Husband | Hanging | 32 | 2.4 | 17 | 2 | Higher | No affiliation or all religions | City | In person | 1:13 | Proactively called by researchers |

| Jurga | 49 | Husband | Hanging | 47 | 2.1 | 26 | 2 | Higher | Not practicing catholic | City | In person | 1:35 | Filled the questionnaire |

| Agnė | 36 | Husband | Cutting veins | 44 | 5 | 8 | 2 | Higher | Catholic | Town | Videocall | 1:28 | Filled the questionnaire |

| Dalia | 62 | Husband | Hanging | 57 | 5 | 39 | 2 | Higher | Catholic | City | Videocall | 2:03 | Proactively called by researchers |

| Asta | 36 | Husband | Hanging | 32 | 4 | 17 | 1 | Higher | Eastern orthodox | City | Videocall | 2:09 | Proactively called by researchers |

| Average | 40.64 | 41 | 3.59 | 17.89 | 1:41 | ||||||||

| SD | 9.98 | 9.63 | 1.35 | 11.2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Čepulienė, A.A.; Skruibis, P. The Role of Spirituality during Suicide Bereavement: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148740

Čepulienė AA, Skruibis P. The Role of Spirituality during Suicide Bereavement: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(14):8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148740

Chicago/Turabian StyleČepulienė, Austėja Agnietė, and Paulius Skruibis. 2022. "The Role of Spirituality during Suicide Bereavement: A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 14: 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148740

APA StyleČepulienė, A. A., & Skruibis, P. (2022). The Role of Spirituality during Suicide Bereavement: A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8740. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148740