Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews

Abstract

:1. Introduction

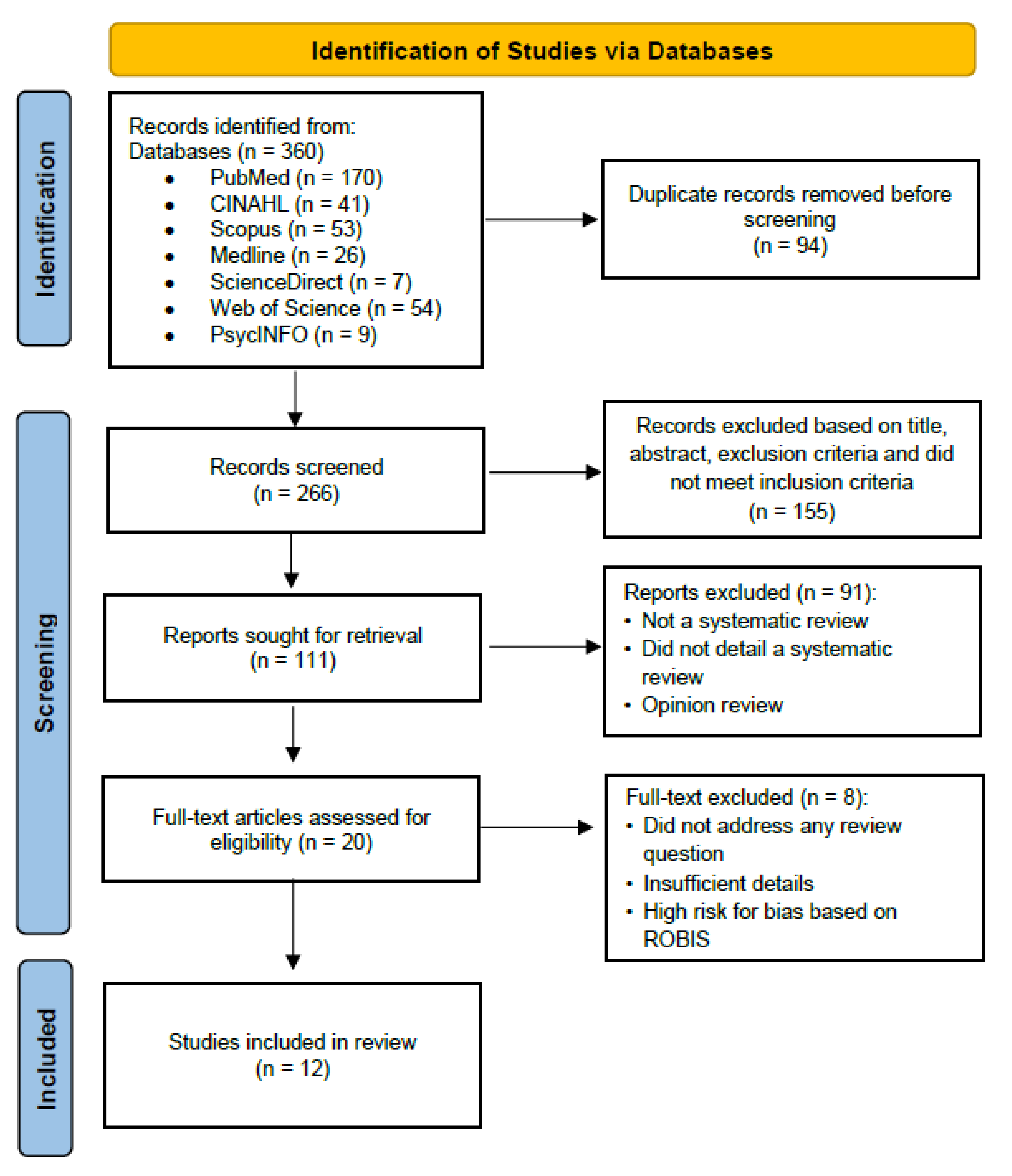

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Defining the Review Questions

- What are the prevalence and trends in workplace bullying among nurses?

- What are the antecedents for workplace bullying among nurses?

- What are the consequences of workplace bullying for nurses?

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Article Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Question 1—What Are the Prevalence and Trends in Workplace Bullying among Nurses?

| No. | Evidence/Reference | Prevalence Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Spector et al. (2014) [18] | Prevalence rate: 25–66.9%. Specific: Physical violence (36.4%), non-physical (66.9%), bullying and others (39.7%), sexual harassment (25%), injured (32.7%). |

| 2. | Houck and Colbert (2017) [3] | Prevalence of bullying among nurses was observed to be between 26% and 77%. |

| 3. | Bambi et al. (2018) [20] | % of bullying prevalence: 2.4 to 81%. % of workplace incivility: 67.5 to 90.4%. % of lateral violence (peer violence): 1 to 87.4%. |

| 4 | Hartin et al. (2018) [14] | 61% of respondents in Australia reported workplace bullying events within the last 12 months. |

| 5. | Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] | Prevalence ranged widely from 0.3 to 73.1% (variations attributed to the workplace context and instrument measuring workplace bullying events [e.g., daily basis, over the past 1 month, or over the past 12 months]). Studies measuring workplace bullying within past 6–12 months reported a more consistent prevalence ranging from 25.6 to 73.1%. |

| 6. | Lever et al. (2019) [8] | Bullying prevalence ranged from 3.9 to 86.5%, with a pooled mean estimate of 26.3%. The pooled mean prevalence of bullying by region: Asia (47.1%), Australia (36.1%), Europe (18.4%), and North America (24.5%). |

| 7. | Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] | % of bullying prevalence in emergency department setting: 60%. % of bullying prevalence in Operating Room setting: 59% witnessed workplace bullying events, but only 6% self-reported such events in the USA. |

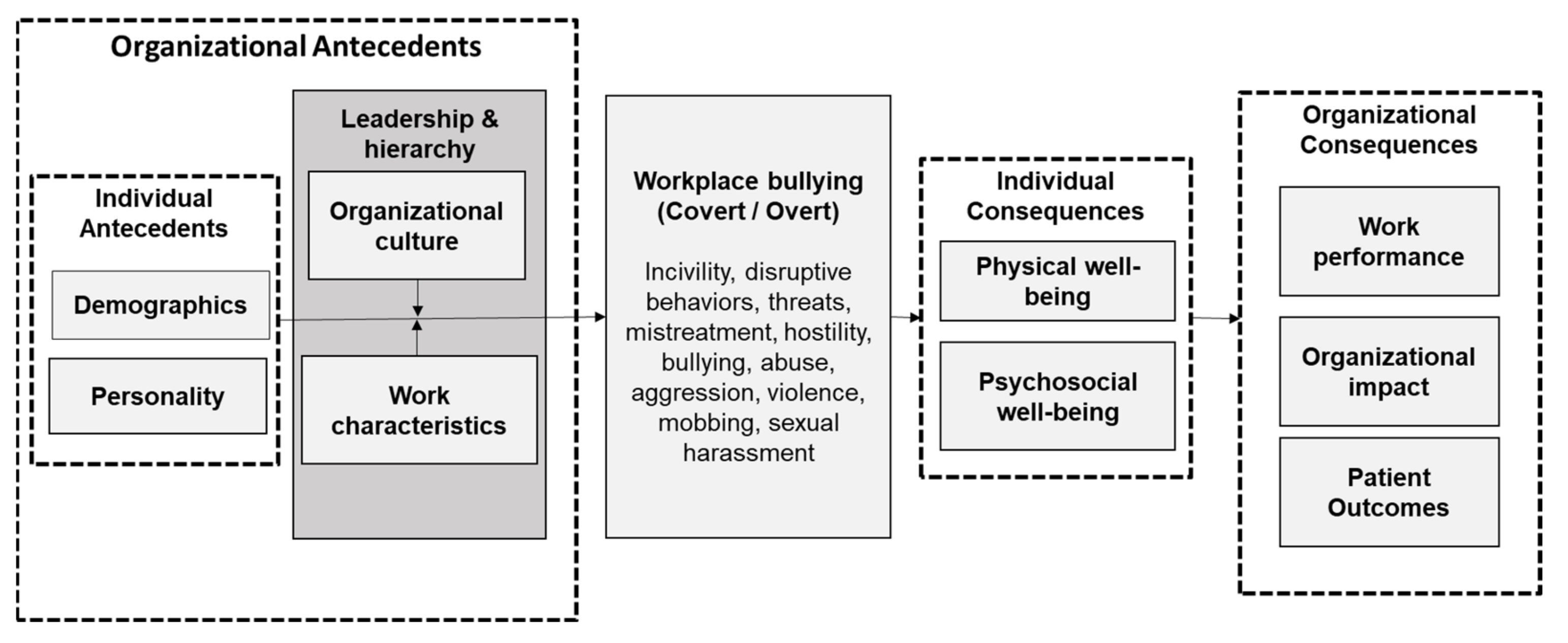

3.2. Question 2—What Are the Antecedents for Workplace Bullying among Nurses?

3.2.1. Individual-Level Antecedents

3.2.2. Organizational-Level Antecedents

| No. | Types of Antecedents | Subtypes | Association | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Demographics (Individual-level) | Age | Negatively associated with workplace bullying. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] Crawford et al. (2019) [21] |

| Length of experience/service | Negatively associated with workplace bullying. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| Gender | No association. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| Marital status | No association. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| Education level | No association. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| Minority race or ethnicity | Association reported in Anglo, Southern Asia. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| Disability | Association reported in Anglo. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| Having children | Association reported in Latin America and Eastern Europe. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| 2. | Personality (Individual-level) | Locus of control/assertiveness | Lower locus of control (assertiveness) is negatively associated with workplace bullying. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] |

| Psychological capital | Less psychological capital is negatively associated with workplace bullying. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| Vulnerable traits or personality/poor compliance to social norms | Negatively associated with workplace bullying. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | ||

| 3. | Organizational culture (Organizational-level) | Organizational culture promotes staff empowerment, distributive justice, and zero tolerance for bullying/Magnet® organizational culture | Perceived healthy work environment is negatively associated with workplace bullying. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] Pfeifer and Vessey (2017) [19] |

| Quality of interpersonal relationships | Association varies according to regions. Vertical bullying was most prevalent in higher power distance cultures, whereas horizontal bullying was either more or equally prevalent in lower power distance cultures. | Crawford et al. (2019) [21] Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] | ||

| 4. | Work characteristics (Organizational-level) | Work overload | Higher workload is positively associated with workplace bullying. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] Trépanier et al. (2016) [4] |

| Staff shortages | More severe staff shortages are positively associated with workplace bullying. | Trépanier et al. (2016) [4] | ||

| Stressful working conditions | High-stress work environment is positively associated with workplace bullying. | Trépanier et al. (2016) [4] | ||

| 5. | Leadership and hierarchy (Organizational-level) | Leadership styles | Autocratic, unsupportive, and disengaged leadership tends to perpetuate high-power distance clusters and increased bullying behaviors. | Trépanier et al. (2016) [4] Crawford et al. (2019) [21] Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] |

3.3. Question 3—What Are the Consequences of Workplace Bullying for Nurses?

3.3.1. Psychosocial Well-Being

3.3.2. Physical Well-Being

3.3.3. Work Performance

3.3.4. Organizational Impact

3.3.5. Patient Outcomes

| No. | Types of Consequences | Subtypes | Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Psychosocial well-being | Psychological stress | Hartin et al. (2018) [14]; Bambi et al. (2018) [20]; Hawkins et al. (2019) [22]; Crawford et al. (2019) [21]; Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] |

| Depression | Hartin et al. (2018) [14]; Bambi et al. (2018) [20]; Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] | ||

| Burnout | Hartin et al. (2018) [14]; Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] | ||

| Professional confidence | Hartin et al. (2018) [14] | ||

| Sense of self-worth | Hartin et al. (2018) [14] | ||

| Work motivation | Hartin et al. (2018) [14]; Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] | ||

| 2. | Physical well-being | Sleep-related issues | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16]; Lever et al. (2019) [8] |

| Headaches | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16]; Lever et al. (2019) [8] | ||

| Gastrointestinal problems, and to a lesser extent, | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16]; Lever et al. (2019) [8] | ||

| Back and joint pain | Lever et al. (2019) [8] | ||

| Cardiac-related symptoms, tachycardia, or blood pressure changes | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16]; Lever et al. (2019) [8] | ||

| Sick leave/absenteeism | Bambi et al. (2018) [20]; Lever et al. (2019) [8]; Hawkins et al. (2019) [22]; Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] | ||

| 3. | Work performance | Avoidance behavior, delay in effective communication, or impaired peer relations | Hutchinson and Jackson (2013) [17]; Houck and Colbert (2017) [3]; Crawford et al. (2019) [21]; Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] |

| Poor concentration at work, preventing them from delivering safe and effective nursing care | Hutchinson and Jackson (2013) [17]; Houck and Colbert (2017) [3]; Bambi et al. (2018) [20]; Hawkins et al. (2019) [22]; Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] | ||

| Fail to raise safety concerns and seek assistance/delayed care | Hutchinson and Jackson (2013) [17]; Houck and Colbert (2017) [3]; Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] | ||

| Become hostile and perpetrators of similar bullying behaviors | Hutchinson and Jackson (2013) [17] | ||

| 4. | Organizational impact | Job dissatisfaction | Hartin et al. (2018) [14]; Hawkins et al. (2019) [22]; Crawford et al. (2019) [21]; Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] |

| Increased intention to quit | Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] | ||

| Increased staff turnover/attrition rate | Bambi et al. (2018) [20]; Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23]; Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] | ||

| Higher organizational costs due to recruitment and retention difficulties | Johnson and Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] | ||

| 5. | Patient outcomes | Patient falls | Houck and Colbert (2017) [3] |

| Errors in treatments or medications | Houck and Colbert (2017) [3] | ||

| Adverse event or patient mortality | Houck and Colbert (2017) [3] | ||

| Patient satisfaction or patient complaints | Houck and Colbert (2017) [3] Hutchinson and Jackson (2013) [17] |

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence and Trends of Workplace Bullying among Nurses

4.2. Antecedents of Workplace Bullying among Nurses

4.3. Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of This Umbrella Review

4.5. Implications for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castronovo, M.A.; Pullizzi, A.; Evans, S. Nurse Bullying: A Review and a Proposed Solution. Nurs. Outlook 2016, 64, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S.V. What We Know, What We Do Not Know, and What We Should and Could Have Known about Workplace Bullying: An Overview of the Literature and Agenda for Future Research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 42, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houck, N.M.; Colbert, A.M. Patient Safety and Workplace Bullying: An Integrative Review. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 2017, 32, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trépanier, S.-G.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S.; Boudrias, V. Work Environment Antecedents of Bullying: A Review and Integrative Model Applied to Registered Nurses. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 55, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Matthiesen, S.B.; Einarsen, S. The Impact of Methodological Moderators on Prevalence Rates of Workplace Bullying. A Meta-analysis. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 955–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwell, J.; Demir, D. Psychological Consequences of Bullying for Hospital and Aged Care Nurses. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2012, 59, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudrias, V.; Trépanier, S.-G.; Salin, D. A Systematic Review of Research on the Longitudinal Consequences of Workplace Bullying and the Mechanisms Involved. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2021, 56, 101508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lever, I.; Dyball, D.; Greenberg, N.; Stevelink, S.A.M. Health Consequences of Bullying in the Healthcare Workplace: A Systematic Review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 3195–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laschinger, H.K.S.; Wong, C.A.; Grau, A.L. The Influence of Authentic Leadership on Newly Graduated Nurses’ Experiences of Workplace Bullying, Burnout and Retention Outcomes: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havaei, F.; Astivia, O.L.O.; MacPhee, M. The Impact of Workplace Violence on Medical-Surgical Nurses’ Health Outcome: A Moderated Mediation Model of Work Environment Conditions and Burnout Using Secondary Data. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 109, 103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, M.; Fernandes, R.; Becker, L.; Pieper, D.; Hartling, L. Chapter V: Overviews of Reviews. Draft Version (8 October 2018). Cochrane Handb. Syst. Rev. Interv. Lond. Cochrane 2018. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-v (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Hunt, H.; Pollock, A.; Campbell, P.; Estcourt, L.; Brunton, G. An Introduction to Overviews of Reviews: Planning a Relevant Research Question and Objective for an Overview. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whiting, P.; Savović, J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Caldwell, D.M.; Reeves, B.C.; Shea, B.; Davies, P.; Kleijnen, J.; Churchill, R. ROBIS: A New Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews was Developed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 69, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hartin, P.; Birks, M.; Lindsay, D. Bullying and the Nursing Profession in Australia: An Integrative Review of the Literature. Collegian 2018, 25, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, D.E.; Gillespie, G.L.; Smith, C.R. Interventions against Bullying of Prelicensure Students and Nursing Professionals: An Integrative Review. In Nursing forum; Wiley: Hoboken, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 54, pp. 84–90. [Google Scholar]

- Karatuna, I.; Jönsson, S.; Muhonen, T. Workplace Bullying in the Nursing Profession: A Cross-Cultural Scoping Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 111, 103628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, M.; Jackson, D. Hostile Clinician Behaviours in the Nursing Work Environment and Implications for Patient Care: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. BMC Nurs. 2013, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spector, P.E.; Zhou, Z.E.; Che, X.X. Nurse Exposure to Physical and Non-physical Violence, Bullying, and Sexual Harassment: A Quantitative Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014, 51, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, L.E.; Vessey Lauren, E. An Integrative Review of Bullying and Lateral Violence among Nurses in Magnet Organizations. Policy Polit. Nurs. Pract. 2017, 18, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bambi, S.; Foà, C.; De Felippis, C.; Lucchini, A.; Guazzini, A.; Rasero, L. Workplace Incivility, Lateral Violence and Bullying among Nurses. A Review about Their Prevalence and Related Factors. Acta Bio Med. Atenei Parm. 2018, 89, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, C.L.; Chu, F.; Judson, L.H.; Cuenca, E.; Jadalla, A.A.; Tze-Polo, L.; Kawar, L.N.; Runnels, C.; Garvida, R., Jr. An Integrative Review of Nurse-to-Nurse Incivility, Hostility, and Workplace Violence: A GPS for Nurse Leaders. Nurs. Adm. Q. 2019, 43, 138–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, N.; Jeong, S.; Smith, T. New Graduate Registered Nurses’ Exposure to Negative Workplace Behaviour in the Acute Care Setting: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2019, 93, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, A.H.; Benham-Hutchins, M. The Influence of Bullying on Nursing Practice Errors: A Systematic Review. AORN J. 2020, 111, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, M.; Hunt, G.E.; Horsfall, J. Identifying and Addressing Bullying in Nursing. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 31, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartin, P.; Birks, M.; Lindsay, D. Bullying in Nursing: Is It in the Eye of the Beholder? Policy. Polit. Nurs. Pract. 2019, 20, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, M.B.; Einarsen, S. Outcomes of Exposure to Workplace Bullying: A Meta-Analytic Review. Work Stress 2012, 26, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.; Agarwal, U.A. Workplace Bullying: A Review and Future Research Directions. South Asian J. Manag. 2016, 23, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S.J. Lateral Violence in Nursing: A Review of the Past Three Decades. Nurs. Sci. Q. 2015, 28, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samnani, A.-K.; Singh, P. 20 Years of Workplace Bullying Research: A Review of the Antecedents and Consequences of Bullying in the Workplace. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2012, 17, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neall, A.M.; Tuckey, M.R. A Methodological Review of Research on the Antecedents and Consequences of Workplace Harassment. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2014, 87, 225–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapf, D.; Escartin, J.; Scheppa-Lahyani, M.; Einarsen, S.V.; Hoel, H.; Vartia, M. Empirical Findings on Prevalence and Risk Groups of Bullying in the Workplace. Bullying Harass. Work. Theory Res. Pract. 2020, 3, 105–162. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Lee, M. Pooled Prevalence of Workplace Bullying in Nursing: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Korean Crit. Care Nurs. 2016, 9, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S.L. An Ecological Model of Workplace Bullying: A Guide for Intervention and Research. In Nursing Forum; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 46, pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, A.; Agarwal, U.A. A Review of Literature on Mediators and Moderators of Workplace Bullying: Agenda for Future Research. Manag. Res. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mento, C.; Silvestri, M.C.; Bruno, A.; Muscatello, M.R.A.; Cedro, C.; Pandolfo, G.; Zoccali, R.A. Workplace Violence against Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 51, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.L. International Perspectives on Workplace Bullying among Nurses: A Review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2009, 56, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, R.N.; de Guirardello, E.B. Bullying in the Nursing Work Environment: Integrative Review. Rev. Gauch. Enferm. 2019, 40, e20190176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillen, P.A.; Sinclair, M.; Kernohan, W.G.; Begley, C.M.; Luyben, A.G. Interventions for Prevention of Bullying in the Workplace. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagg, S.J.; Sheridan, D. Effectiveness of Bullying and Violence Prevention Programs: A Systematic Review. Aaohn J. 2010, 58, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| S/N | Article | Objectives | Review Typology | Search Strategy | Number of Included Studies/Total Participants | Geographical Location | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Hutchinson & Jackson (2013) [17] | To examine the relationship between the various forms of hostile clinician behaviors and patient care. | A mixed-methods systematic review | 8 databases (CINAHL, Health Collection (Informit), Medline (Ovid), Ovid, ProQuest Health and Medicine, PsycINFO, PubMed and Cochrane library), including hand searching of reference lists. Search period: Between 1990 and 2011. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 30 studies N = 102,909 | USA (16), Australia (7), Canada (3), United Kingdom (1), New Zealand (1), Iceland (1), Finland (1) | Q3: Consequences on patient safety included:

|

| 2. | Spector et al. (2014) [18] | To provide a quantitative review that estimates exposure rates by type of violence, setting, source, and world region. | A quantitative review | 5 databases (Embase, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed and Web of Science). Search period: From earliest date to October 2012. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 136 studies N = 151,347 | Worldwide | Q1: Prevalence & trends: Violence types are divided into:

Prevalence rates:

Geographical locations:

|

| 3. | Trépanier et al. (2016) [4] | To provide an overview of the current state of knowledge on work environment antecedents of workplace bullying. | Systematic review with narrative synthesis | 3 databases (PsycINFO, ProQuest and CINAHL). Search period: From earliest date to 2014. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 12 studies N = 4177 | North America (7), Australia (3), Turkey (2) | Q2: Identified four main categories of work-related antecedents of workplace bullying: (a) job characteristics, (b) quality of interpersonal relationships, (c) leadership styles, and (d) organizational culture. |

| 4. | Houck & Colbert (2017) [3] | To explore and synthesize the published articles that address the impact of workplace nurse bullying on patient safety. | Integrative review | 5 databases (PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane library and MEDLINE). Search period: Between 1995 and March 2016. Inclusion:

| 11 studies N = 16,137 | USA (7), Australia (2), Canada (1), and United Kingdom (1) | Q3: The effect of bullying on nurses’ work was not sufficient to reveal all risks to patient safety.

|

| 5. | Pfeifer & Vessey (2017) [19] | To synthesize and evaluate the existing literature on workplace bullying and lateral violence in the Magnet® setting. | Integrative review | 5 databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Cochrane library and Web of Science). Search period: Between January 2008 and February 2017. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 11 studies N = 7657 | USA | Q2: Magnet nurses reported lower WB scores than nurses working in non-Magnet organizations (based on four studies). |

| 6. | Bambi et al. (2018) [20] | To detect specifically the prevalence of workplace incivility (WI), lateral violence (LV), and bullying among nurses. | Narrative review | 3 databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL and Embase). Search period: No time limitation. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| Workplace incivility:16 studies N = 12,246 Lateral violence:25 studies N = 25,375 | Workplace incivility: Canada (8), USA (5), China (1), Egypt (1), Pakistan (1) Lateral violence: USA (15), Europe (5), Asia (2)—Turkey & South Korea, South Africa (1), New Zealand (1), Jamaica (1) | Q1: Prevalence:

Q3: Consequences:

|

| 7. | Hartin et al. (2018) [14] | To discuss the current state of knowledge about bullying in the nursing profession in Australia. | Integrative review | 3 databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL and Scopus). Search period: Between January 1991 and December 2016. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 23 studies N = 16,168 | Australia | Q1: 61% of respondents reported WB within the last 12 months. Nurse-to-nurse aggression was the most distressing type of bullying, and statistics were likely to be under-reported. Q3:

|

| 8. | Crawford et al. (2019) [21] | To examine the evidence regarding nurse-to-nurse incivility, bullying, and workplace violence for the 4 nursing populations (student nurses, new graduate nurses, experienced nurses, and academic faculty). | Integrative review | 6 databases (CINAHL, Cochrane library, Embase, ERIC, PsycINFO, and PubMed). Include Google Search. Search period: Between 2010 and 2016. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 21 studies N = Not reported | USA and Canada | Q1: No number reported. Highlighted that WB prevalence rates among nurses have not changed in more than 20 years. Q2: Antecedents were divided into 3 layers of WB triggers: organizational, work environment, and personal. Suggested that young nurses were at a higher risk. Q3: Identified 84 negative academic, organizational, work unit, and personal outcomes. Others:

|

| 9. | Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] | To synthesize evidence on negative workplace behavior experienced by new graduate nurses in acute care setting and discuss implications for the nursing profession. | Integrative review | 5 databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, ProQuest, JBI and Scopus). Search period: Between 2007 and 2017. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 16 studies (14 published articles & 2 dissertations) N = 3043 | Canada (6), USA (3), Australia (2), Taiwan (2), Ireland (1), South Korea (1), Singapore (1) | Q1:

Q2: Three antecedents were identified:

Q3: Individual impact and patient care identified:

Others:

|

| 10. | Lever et al. (2019) [8] | To review both mental and physical health consequences of bullying for healthcare employees. | Systematic review (quantitative studies) | 5 databases (Embase MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed and Web of Science). Search period: Between 2005 and January 2017. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 45 studies N = varied from 61 to 9949. | 15 studies in North America (Canada-10; USA-5) 15 studies in Europe (UK-4; Denmark-4; Norway-3; Portugal-2; Germany-1; Bosnia-1) 6 studies in Australia (6) 7 studies in Asia (Turkey-4; Japan-2; China-1) 2 studies (Mixed profiles) | Q1: Prevalence:

Q3: Consequences divided into 2 types:

|

| 11. | Johnson & Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] | To examine the influence of nurse bullying on nursing practice errors and patient outcomes. | A systematic review (involving qualitative synthesis) | 4 databases (CINAHL, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, and PsycINFO). Search period: Between January 2012 and November 2017. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 14 studies N = Not reported | Not reported | Q1: ED setting: 60% of respondents reported WB events. OR setting: 59% witnessed WB events, but only 6% self-reported such events in perioperative environment in the USA. Two types of bullying trends were identified: (a) work-related bullying originating from workplace environment, and (b) person-related bullying originating from informal personal relationships. Q3: Consequences included:

|

| 12. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] | To examine WB research among nurses with the focus on sources, antecedents, outcomes, and coping responses from a cross-cultural perspective during the years 2001–2019. | A cross-cultural scoping review | 4 databases (CINAHL, PubMed, PsycINFO and Web of Science). Search period: Between 2001 and 2019. Inclusion:

Exclusion:

| 166 studies N = Not reported | 29 countries worldwide, although research was mostly conducted in the Anglo cluster | Q2: Antecedents varied across cultures and classified as: (a) individual (demographics and personality traits); (b) organizational (leadership, work characteristics, and organizational culture). Other results included:

Q3: Consequences:

|

| S/N | Article | Quality of Study Using ROBIS Tool | Strengths | Limitations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | O | ||||

| 1. | Hutchinson & Jackson (2013) [17] Mixed-methods systematic review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 2. | Spector et al. (2014) [18] Quantitative review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 3. | Trépanier et al. (2016) [4] Systematic review with narrative synthesis |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 4. | Houck & Colbert (2017) [3] Integrative review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 5. | Pfeifer & Vessey (2017) [19] Integrative review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 6. | Bambi et al. (2018) [20] Narrative review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 7. | Hartin et al. (2018) [14] Integrative review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 8. | Crawford et al. (2019) [21] Integrative review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 9. | Hawkins et al. (2019) [22] Integrative review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 10. | Lever et al. (2019) [8] Systematic review (quantitative studies) |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 11. | Johnson & Benham-Hutchins (2020) [23] Systematic review (involving qualitative synthesis |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

| 12. | Karatuna et al. (2020) [16] Scoping review |  |  |  |  |  |

|

|

: Low risk for bias;

: Low risk for bias;  : Some concerns for bias;

: Some concerns for bias;  : high risk for bias.

: high risk for bias. | Concepts/Terms | Examples |

|---|---|

| Sources | Management, leaders, peers, non-nursing colleagues, patients, and family members |

| Direction | Horizontal, lateral, and vertical |

| Manifestations | Incivility, disruptive behaviors, threats, mistreatment, hostility, bullying, abuse, aggression, violence, mobbing, sexual harassment |

| Forms | Covert behaviors (e.g., sabotage, withholding support) and overt forms (verbal and physical) |

| Measurement instruments |

|

| Theories |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goh, H.S.; Hosier, S.; Zhang, H. Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148256

Goh HS, Hosier S, Zhang H. Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(14):8256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148256

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoh, Hongli Sam, Siti Hosier, and Hui Zhang. 2022. "Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 14: 8256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148256

APA StyleGoh, H. S., Hosier, S., & Zhang, H. (2022). Prevalence, Antecedents, and Consequences of Workplace Bullying among Nurses—A Summary of Reviews. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8256. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148256