COVID-19 Victimization Experience and College Students’ Mobile Phone Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Effect of Future Anxiety and Mindfulness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Social Cognitive Theory

1.2. COVID-19 Victimization Experience and Mobile Addiction

1.3. Mediating Role of Future Anxiety

1.4. Moderating Role of Mindfulness

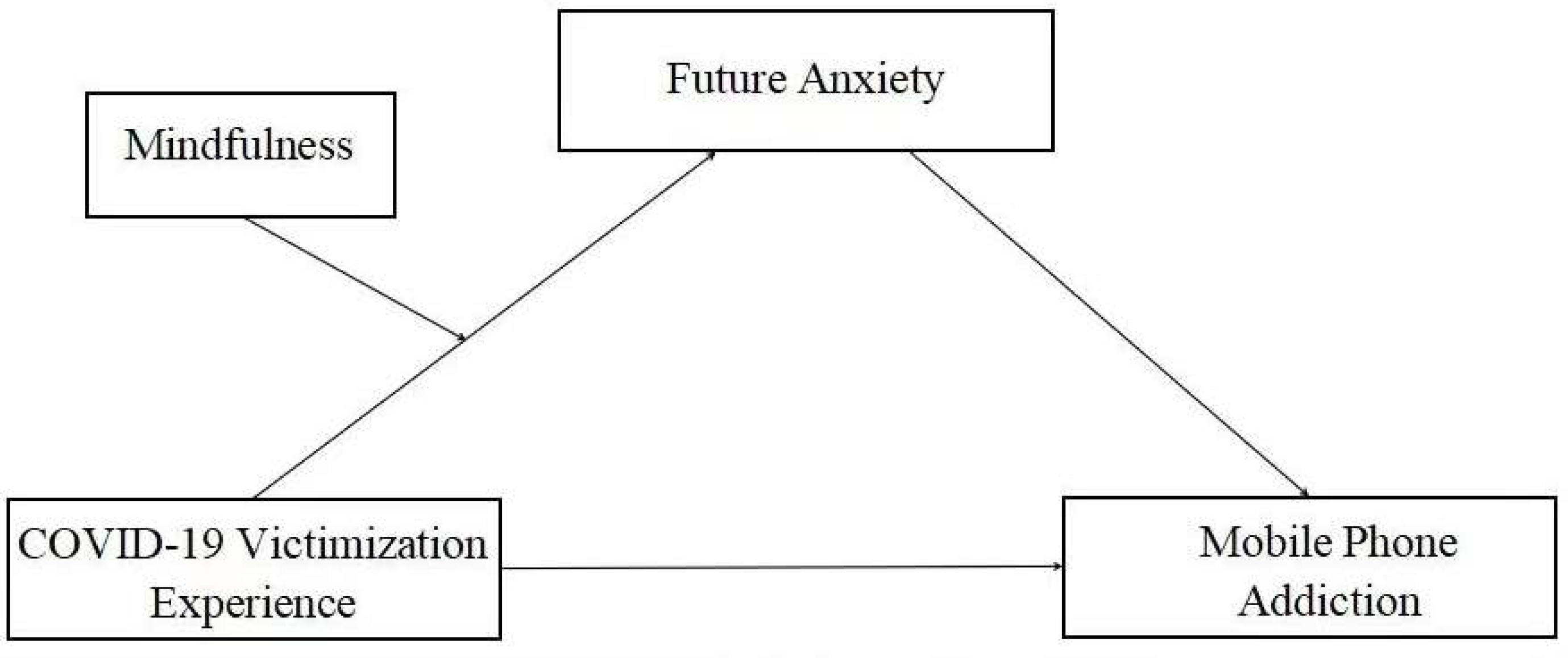

1.5. The Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Approval

2.2. Participants and Procedure

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. COVID-19 Victimization Experience Scale

2.3.2. Mobile Phone Addiction Scale

2.3.3. Future Anxiety Scale

2.3.4. Mindfulness Scale

2.3.5. Data Analysis

- Descriptive statistics were performed on the participants’ background information, indicating the proportion of participants’ composition.

- Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were performed for each variable, with descriptive statistics reflecting each variable’s means and standard deviations. Pearson’s correlation test was used to analyze the correlation between each variable and dimension. When the correlation coefficient should be less than 0.7 [51], indicating no collinearity problem in all variables, then the regression analysis could be performed.

- The value of Cronbach’s α tested the reliability of each scale. Values greater than 0.7 indicated the excellent reliability of the measurement instrument [52].

- The common method variance (CMV) was tested as well as the unrotated factor analysis by Harman’s One-Factor Test; when the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) was greater than 0.8, Bartlett test of sphericity reached significance. The explanatory power of the first factor should not exceed the marginal value of 50% [53], indicating that the CMV problem is not significant.

- The mediating effect of future anxiety was tested using model 4 of the Hayes PROCESS plug-in with COVID-19 victimization experience as the independent variable and mobile phone addiction as the dependent variable; mindfulness was added as the moderating variable in the model 7 of the Hayes PROCESS plug-in to test the moderated mediation model. Additionally, the Bootstrap confidence interval was set to 95%, and the sample size was set to 5000. The CI (from the lower limit of confidence interval (LLCI) to the upper limit of confidence interval (ULCI)) of each path coefficient should not contain 0, meaning a significant effect [54].

- The factor loadings of the measurement models were tested with the criterion of greater than 0.5. The values of composite reliability (CR) were tested with the criterion of greater than 0.7. Moreover, the values of average variance extracted (AVE) were tested with the criterion of greater than 0.5. All the above indicators were satisfied, indicating the good convergent validity of the scales [51].

- The fitness of the measurement model was tested using the following essential indicators. The Chi-square value should not be significant (p > 0.05). However, considering the sensitivity of the Chi-square value to the large sample size (when the sample size is large, the Chi-square value can easily reach significance), it was not reported in this study and other indicators were tested and referred to [55]. Namely, root mean square residual (RMR) < 0.08; standardized RMR (SRMR) = < 0.08; comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.85; goodness-of-fit index (GFI) > 0.85; normed fit index (NFI) > 0.85; Tucker–Lewis index (TLI) > 0.80 and incremental fit index (IFI) > 0.85 [56]. If the above criteria were met, the measured model fitness was acceptable.

- The square root of AVE was performed to assess the discriminant validity of each dimension of the measurement model, with the criterion of the square root of AVE greater than the correlation coefficient in each dimension [57].

3. Results

3.1. Participants’ Composition

3.2. Measurement Model

3.2.1. COVID-19 Victimization Experience Scale

3.2.2. Mobile Phone Addiction Scale

3.2.3. Future Anxiety Scale

3.2.4. Mindfulness Scale

3.3. Discriminant Validity

3.4. Common Method Variance (CMV) Test

3.5. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.6. Mediating Role of Future Anxiety

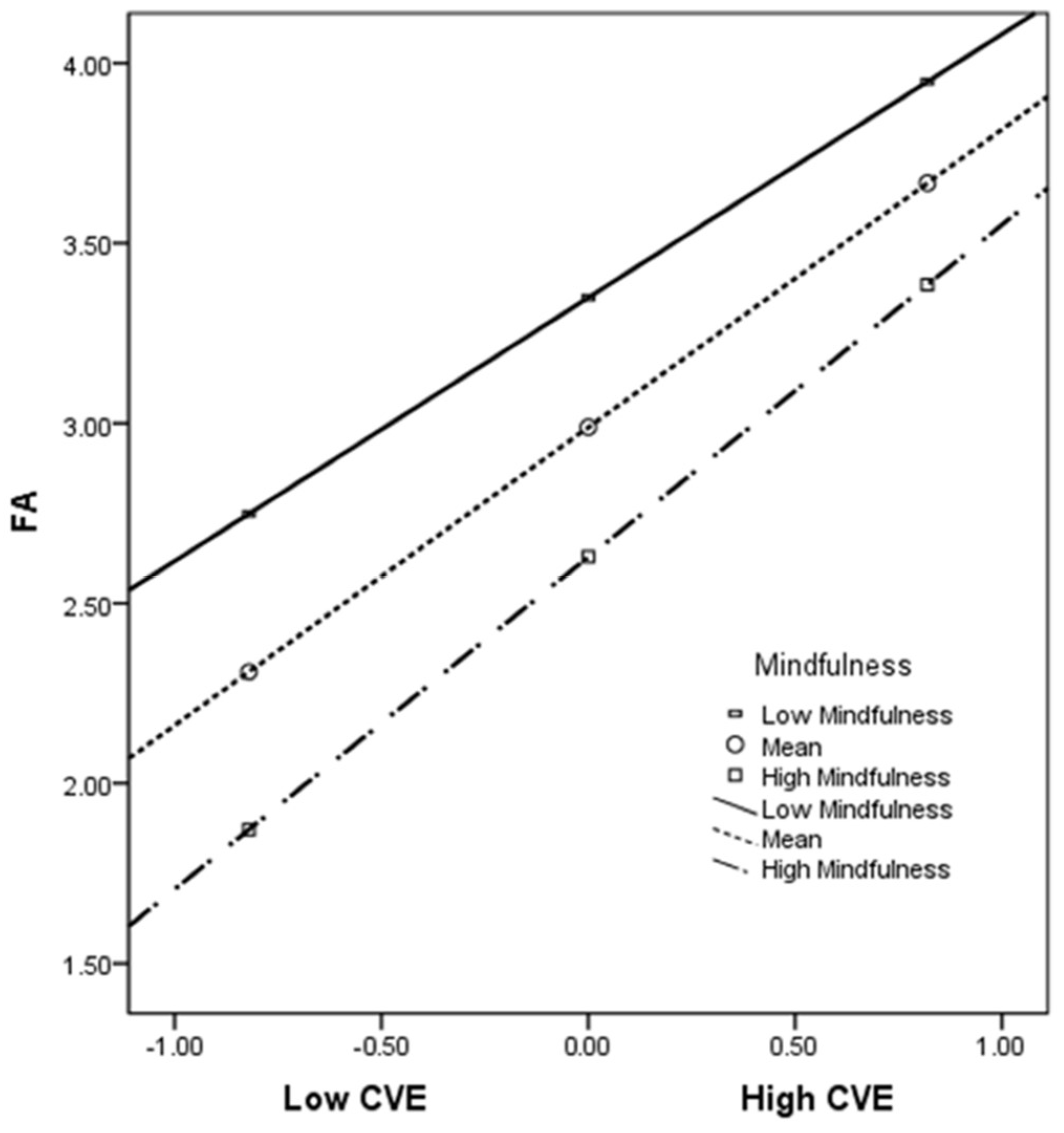

3.7. Moderating Role of Mindfulness

4. Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

4.2. Practical Contributions

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Listings of WHO’s Response to COVID-19. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-06-2020-covidtimeline (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Iyengar, K.; Upadhyaya, G.K.; Vaishya, R.; Jain, V. COVID-19 and applications of smartphone technology in the current pandemic. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, G.; Scalzo, L.L.; Giuffrè, M.; Ferrara, P.; Corsello, G. Smartphone use and addiction during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: Cohort study on 184 Italian children and adolescents. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Z.; Wei, Q.; Hong, J.C. Cellphone addiction during the Covid-19 outbreak: How online social anxiety and cyber danger belief mediate the influence of personality. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 121, 106790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Liu, B.; Fang, J. Stress and problematic smartphone use severity: Smartphone use frequency and fear of missing out as mediators. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 659288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.X. A systematic review of prevention and intervention strategies for smartphone addiction in students: Applicability during the covid-19 pandemic. J. Evid. Based Psychother. 2021, 21, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, G.A.; Jagaveeran, M.; Goh, Y.N.; Tariq, B. The impact of type of content use on smartphone addiction and academic performance: Physical activity as moderator. Technol. Soc. 2021, 64, 101521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kil, N.; Kim, J.; McDaniel, J.T.; Kim, J.; Kensinger, K. Examining associations between smartphone use, smartphone addiction, and mental health outcomes: A cross-sectional study of college students. Health Promot. Perspect. 2021, 11, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.Y.; Kim, D.J.; Park, J.W. Stress and adult smartphone addiction: Mediation by self-control, neuroticism, and extraversion. Stress Health 2017, 33, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayis, A.R.; Satici, B.; Deniz, M.E.; Satici, S.A.; Griffiths, M.D. Fear of COVID-19, loneliness, smartphone addiction, and mental wellbeing among the Turkish general population: A serial mediation model. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al. Qudah, M.F.; Albursan, I.S.; Hammad, H.I.; Alzoubi, A.M.; Bakhiet, S.F.; Almanie, A.M.; Alenizi, S.S.; Aljomaa, S.S.; Al-Khadher, M.M. Anxiety about COVID-19 infection, and its relation to smartphone addiction and demographic variables in Middle Eastern countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.Y.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, H.B.; Zhou, H.L. Adult attachment: Its mediation role on childhood trauma and mobile phone addiction. J. Psychol. Africa 2021, 31, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, M.R.; Apaolaza, V.; Fernandez-Robin, C.; Hartmann, P.; Yañez-Martinez, D. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on subjective mental well-being: The interplay of perceived threat, future anxiety and resilience. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 170, 110455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przepiorka, A.; Blachnio, A.; Cudo, A. Procrastination and problematic new media use: The mediating role of future anxiety. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubbs, J.D.; Savage, J.E.; Adkins, A.E.; Amstadter, A.B.; Dick, D.M. Mindfulness moderates the relation between trauma and anxiety symptoms in college students. J. Am. Coll. Health 2019, 67, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentics-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, L.; You, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, R. Who overuses smartphones? Roles of virtues and parenting style in smartphone addiction among Chinese college students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 65, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, M.; Baytemir, K.; Inceman-Kara, F. Duration of daily smartphone usage as an antecedent of nomophobia: Exploring multiple mediation of loneliness and anxiety. Behav. Inform. Technol. 2021, 40, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.C.; Yang, T.A.; Lee, J.C. The relationship between smartphone addiction, parent–child relationship, loneliness and self-efficacy among senior high school students in Taiwan. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohme, J.; Abeele, M.M.P.V.; Van Gaeveren, K.; Durnez, W.; De Marez, L. Staying informed and bridging “social distance”: Smartphone news use and mobile messaging behaviors of flemish adults during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Socius Sociol. Res. Dyn. World 2020, 6, 237802312095019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaeli, N.; Farhadi, H. Prevalence of Internet-based addictive behaviors during COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Addict. Dis. 2021, 39, 468–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhai, J.D.; Yang, H.; McKay, D.; Asmundson, G.J. COVID-19 anxiety symptoms associated with problematic smartphone use severity in Chinese adults. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 274, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Jang, S.I.; Park, E.C.; Shin, J.; Suh, J. Association between the perceived household financial decline due to COVID-19 and smartphone dependency among Korean adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Ye, B.; Yu, L. Peer phubbing and Chinese College students’ smartphone addiction during COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating role of boredom proneness and the moderating role of refusal self-efficacy. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z. Meaning in life as a mediator between interpersonal alienation and smartphone addiction in the context of Covid-19: A three-wave longitudinal study. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 127, 107058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhan, D.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, X. Loneliness and problematic mobile phone use among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of escape motivation and self-control. Addict. Behav. 2021, 118, 106857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, B.; Mao, H.; Hu, R.; Jiang, H. Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction among college students during the 2019 coronavirus disease: The mediating roles of rumination and the moderating role of self-control. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2022, 185, 111222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Chen, J.H.; Tong, K.K.; Yu, E.W.Y.; Wu, A. Problematic smartphone use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Its association with pandemic-related and generalized beliefs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J.; Margraf, J. The relationship between burden caused by coronavirus (COVID-19), addictive social media use, sense of control and anxiety. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 119, 106720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleski, Z. Future anxiety: Concept, measurement, and preliminary research. Pers. Individ. Dif. 1996, 21, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleski, Z.L. ˛ek przed przyszło´sci ˛a. Ramy teoretyczne i wst ˛epne dane empiryczne [Fear of the future. Theoretical frame and preliminary empirical research]. In Wykłady z Psychologii w KUL [Lectures in Psychology at the Catholic University of Lublin]; Januszewski, A., Uchnast, Z., Witkowski, T., Eds.; RW KUL: Lublin, Poland, 1988; pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rettie, H.; Daniels, J. Coping and tolerance of uncertainty: Predictors and mediators of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplaga, M.; Grysztar, M. The association between future anxiety, health literacy and the perception of the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Healthcare 2021, 9, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallonardo, V.; Sampogna, G.; Del Vecchio, V.; Luciano, M.; Albert, U.; Carmassi, C.; Carrà, G.; Cirulli, F.; Dell’Osso, B.; Nanni, M.G.; et al. The impact of quarantine and physical distancing following COVID-19 on mental health: Study protocol of a multicentric Italian population trial. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usher, K.; Durkin, J.; Bhullar, N. The COVID-19 pandemic and mental health impacts. Int. J. Mental Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Annoni, A.M.; Petrocchi, S.; Camerini, A.L.; Marciano, L. The relationship between social anxiety, smartphone use, dispositional trust, and problematic smartphone use: A moderated mediation model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shear, J.; Jevning, R. Pure consciousness: Scientific exploration of meditation techniques. J. Conscious. Stud. 1999, 6, 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dillard, A.J.; Meier, B.P. Trait mindfulness is negatively associated with distress related to COVID-19. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2021, 179, 110955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, B.; Robins, R.W.; Pande, N. Mediating role of selfesteem on the relationship between mindfulness, anxiety, and depression. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2016, 96, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, R.; Ray, S.D.; Cohen, T.A. Mindfulness as a way to cope with COVID-19-related stress and anxiety. Counsell. Psychother. Res. 2021, 21, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saricali, M.; Satici, S.A.; Satici, B.; Gocet-Tekin, E.; Griffiths, M.D. Fear of COVID-19, mindfulness, humor, and hopelessness: A multiple mediation analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, Q.; Fan, C. Mobile phone addiction and adolescents’ anxiety and depression: The moderating role of mindfulness. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goodyear, M.D.; Krleza-Jeric, K.; Lemmens, T. The declaration of Helsinki. BMJ 2007, 335, 624–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, P.; Hu, P. Trait procrastination and mobile phone addiction among Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model of stress and gender. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 614660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Tu, C.C.; Dai, X. The effect of the 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic on college students in Wuhan. Psychol. Trauma: Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2020, 12, S6–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, L. Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Child. Media 2008, 2, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaleski, Z.; Sobol-Kwapinska, M.; Przepiorka, A.; Meisner, M. Development and validation of the Dark Future scale. Time Soc. 2019, 28, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L.A.; Baer, R.A.; Smith, G.T. Assessing mindfulness in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure (CAMM). Psychol. Assess. 2011, 23, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.F.; Chi, X.L.; Zhang, J.T.; Duan, W.J.; Wen, Z.K. Validation of Child and Adolescent Mindfulness Measure(CAMM) in Chinese adolescents. Psychol. Explor. 2019, 39, 250–256. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Wang, C. Current approaches for assessing convergent and discriminant validity with SEM: Issues and solutions. In Academy of Management Proceedings; Atinc, G., Ed.; Academy of Management: Briarcliff Manor, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Balla, J.R.; McDonald, R.P. Goodness-of-fit indexes in confirmatory factor analysis: The effect of sample size. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.; Black, W.C. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2015, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chukwuere, J.E.; Mbukanma, I.; Enwereji, P.C. The financial and academic implications of using smartphones among students: A quantitative study. J. Econom. Econom. Educ. Res. 2017, 18, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Elhai, J.D.; Levine, J.C.; Dvorak, R.D.; Hall, B.J. Non-social features of smartphone use are most related to depression, anxiety and problematic smartphone use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 69, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Li, Y.; Shypenka, V. Loneliness, individualism, and smartphone addiction among international students in China. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2018, 21, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Király, O.; Potenza, M.N.; Stein, D.J.; King, D.L.; Hodgins, D.C.; Saunders, J.B.; Griffiths, M.D.; Gjoneska, B.; Billieux, J.; Brand, M.; et al. Preventing problematic internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus guidance. Compreh. Psychiatry 2020, 100, 152180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, K.Z.K.; Gong, X.; Zhao, S.J.; Lee, M.K.O.; Liang, L. Understanding compulsive smartphone use: An empirical test of a flow-based model. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2017, 37, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deursen, A.J.; Bolle, C.L.; Hegner, S.M.; Kommers, P.A. Modeling habitual and addictive smartphone behavior: The role of smartphone usage types, emotional intelligence, social stress, self-regulation, age, and gender. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breslau, N. The epidemiology of trauma, PTSD, and other posttrauma disorders. Trauma Violence Abus. 2009, 10, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 31, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zis, P.; Artemiadis, A.; Bargiotas, P.; Nteveros, A.; Hadjigeorgiou, G.M. Medical studies during the COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of digital learning on medical students’ burnout and mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanke, E.S.; Schmidt, M.J.; Riediger, M.; Brose, A. Thinking mindfully: How mindfulness relates to rumination and reflection in daily life. Emotion 2020, 20, 1369–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, I.; Chen, A.Z.; Newby, J.M.; Kladnitski, N.; Haskelberg, H.; Millard, M.; Mahoney, A. The uptake and outcomes of an online self-help mindfulness programme during COVID-19. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.W.; Arnkoff, D.B.; Glass, C.R. Conceptualizing mindfulness and acceptance as components of psychological resilience to trauma. Trauma Violence Abus. 2011, 12, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivian, E.; Oduor, H.; Girisha, P.; Mantry, P. Mindfulness at methodist—A prospective pilot study of mindfulness and stress resiliency interventions in patients at a tertiary care medical center. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeun, Y.R.; Kim, S.D. Psychological effects of online-based mindfulness programs during the CoViD-19 pandemic: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dimension | Item | FL | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catastrophic cognition | I do not think anyone has had a worse experience than me | 0.686 | 0.844 | 0.576 |

| I think that what happened to me was the worst | 0.761 | |||

| I frequently think about how bad things have become | 0.772 | |||

| I frequently think about how terrible what had happened to me is | 0.810 | |||

| Trauma symptoms | My body often feels tense | 0.708 | 0.826 | 0.546 |

| I am often worried about becoming infected | 0.622 | |||

| I frequently cannot sleep | 0.805 | |||

| My mood is always fluctuating | 0.805 |

| Dimension | Item | FL | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inability to control craving | 1. Your friends and family complained about your use of the mobile phone | 0.684 | 0.848 | 0.445 |

| 2. You have been told that you spend too much time on your mobile phone | 0.692 | |||

| 3. You have tried to hide from others how much time you spend on your mobile phone | 0.611 | |||

| 4. You have received mobile phone bills you could not afford to pay | 0.574 | |||

| 5. You find yourself engaged on the mobile phone for longer period of time than intended | 0.736 | |||

| 6. You have attempted to spend less time on your mobile phone but are unable to | 0.732 | |||

| 7. You can never spend enough time on your mobile phone | 0.621 | |||

| Feeling anxious and lost | 1. When out of range for some time, you become preoccupied with the thought of missing a call | 0.663 | 0.843 | 0.523 |

| 2. You find it difficult to switch off your mobile phone | 0.772 | |||

| 3. You feel anxious if you have not checked for messages or switched on your mobile phone for some time | 0.834 | |||

| 4. You feel lost without your mobile phone | 0.784 | |||

| 5. If you do not have a mobile phone, your friends would find it hard to get in touch with you | 0.519 | |||

| Withdrawal/escape | 1. You have used your mobile phone to talk to others when you were feeling isolated | 0.857 | 0.805 | 0.588 |

| 2. You have used your mobile phone to talk to others when you were feeling lonely | 0.863 | |||

| 3. You have used your mobile phone to make yourself feel better when you were feeling down | 0.535 | |||

| Productivity loss | 1. You find yourself occupied on your mobile phone when you should be doing other things, and it causes problems | 0.783 | 0.738 | 0.585 |

| 2. Your productivity has decreased as a direct result of the time you spend on the mobile phone | 0.746 |

| Item | FL | CR | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Future anxiety scale | I am afraid that the problems which trouble me now will continue for a long time | 0.795 | 0.897 | 0.638 |

| I am terrified by the thought that I might sometimes face life’s crises or difficulties | 0.868 | |||

| I am afraid that in the future my life will change for the worse | 0.874 | |||

| I am afraid that changes in the economic and political situation will threaten my future | 0.692 | |||

| I am disturbed by the thought that in the future I will not be able to realize my goals | 0.749 |

| Dimension | Item | FL | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness and non-judgment | 1. I get upset with myself for having feelings that do not make sense | 0.734 | 0.819 | 0.436 |

| 2. At school, I walk from class to class without noticing what I am doing | 0.524 | |||

| 3. I keep myself busy so I do not notice my thoughts or feelings | 0.576 | |||

| 4. It is hard for me to pay attention to only one thing at a time | 0.593 | |||

| 5. I think about things that happened in the past instead of thinking about things that are happening right now | 0.742 | |||

| 6. I get upset with myself for having certain thoughts | 0.751 | |||

| Acceptance | 1. I tell myself that I should not feel the way I am feeling | 0.723 | 0.798 | 0.502 |

| 2. I push away thoughts that I do not like | 0.552 | |||

| 3. I think that some of my feelings are bad and that I should not have them | 0.820 | |||

| 4. I stop myself from having feelings that I do not like | 0.711 |

| DIMENSION | NCOV-CC | NCOV-TS | MPA-ICC | MPA-FAL | MPA-ES | MPA-PL | FA | CAM-ANJ | CAM-AC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCOV-CC | 0.759 | ||||||||

| NCOV-TS | 0.668 *** | 0.739 | |||||||

| MPA-ICC | 0.207 *** | 0.230 *** | 0.667 | ||||||

| MPA-FAL | 0.132 *** | 0.203 *** | 0.590 *** | 0.723 | |||||

| MPA-ES | 0.126 *** | 0.124 *** | 0.426 *** | 0.491 *** | 0.767 | ||||

| MPA-PL | 0.162 *** | 0.158 *** | 0.602 *** | 0.472 *** | 0.348 *** | 0.765 | |||

| FA | 0.510 *** | 0.548 *** | 0.354 *** | 0.284 *** | 0.256 *** | 0.317 *** | 0.799 | ||

| CAM-ANJ | −0.252 *** | −0.296 *** | −0.563 *** | −0.534 *** | −0.368 *** | −0.552 *** | −0.412 *** | 0.660 | |

| CAM-AC | −0.059 | −0.060 | −0.290 *** | −0.293 *** | −0.262 *** | −0.262 *** | −0.201 *** | 0.349 *** | 0.709 |

| M | 2.557 | 2.801 | 2.688 | 2.712 | 3.096 | 2.702 | 2.970 | 2.480 | 1.911 |

| SD | 0.912 | 0.884 | 0.778 | 0.912 | 0.923 | 0.858 | 1.319 | 0.706 | 0.757 |

| Variable | M | SD | COVID-19 Victimization Experience | Mobile Phone Addiction | Future Anxiety | Mindfulness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 victimization experience | 2.679 | 0.820 | 1 | |||

| Mobile phone addiction | 2.769 | 0.690 | 0.240 *** | 1 | ||

| Future anxiety | 2.970 | 1.319 | 0.579 *** | 0.382 *** | 1 | |

| Mindfulness | 2.252 | 0.601 | −0.244 *** | −0.625 *** | −0.392 *** | 1 |

| Variable | Model 1 Mobile Phone Addiction | Model 2 Future Anxiety | Model 3 Mobile Phone Addiction | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI | |

| COVID-19 victimization experience | 0.202 *** | 0.028 | (0.136, 0.268) | 0.931 *** | 0.045 | (0.838, 1.023) | 0.02 | 0.033 | (−0.050, 0.095) |

| Future anxiety | 0.191 *** | 0.020 | (0.149, 0.233) | ||||||

| R² | 0.058 | 0.335 | 0.146 | ||||||

| F | 51.228 *** | 421.813 *** | 71.684 *** | ||||||

| Variable | Model 1 Future Anxiety | Model 2 Mobile Phone Addiction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | 95% CI | B | SE | 95% CI | |

| COVID-19 victimization experience | 0.827 *** | 0.044 | (0.728, 0.920) | 0.024 | 0.033 | (−0.047, 0.097) |

| Mindfulness | −0.599 *** | 0.061 | (−0.722, −0.478) | |||

| COVID-19 victimization experience × mindfulness | 0.159 ** | 0.059 | (0.045, 0.275) | |||

| Future anxiety | 0.191 *** 0.020 (0.149, 0.234) | |||||

| R² | 0.407 | 0.146 | ||||

| F | 191.064 *** | 71.684 *** | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Li, J.; Huang, J. COVID-19 Victimization Experience and College Students’ Mobile Phone Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Effect of Future Anxiety and Mindfulness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137578

Chen L, Li J, Huang J. COVID-19 Victimization Experience and College Students’ Mobile Phone Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Effect of Future Anxiety and Mindfulness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(13):7578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137578

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lili, Jun Li, and Jianhao Huang. 2022. "COVID-19 Victimization Experience and College Students’ Mobile Phone Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Effect of Future Anxiety and Mindfulness" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 13: 7578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137578

APA StyleChen, L., Li, J., & Huang, J. (2022). COVID-19 Victimization Experience and College Students’ Mobile Phone Addiction: A Moderated Mediation Effect of Future Anxiety and Mindfulness. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 7578. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137578