Abstract

Energy use in buildings can influence the indoor environment. Studies on green buildings, energy saving measures, energy use, fuel poverty, and ventilation have been reviewed, following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. The database PubMed was searched for articles published up to 1 October 2020. In total, 68 relevant peer-reviewed epidemiological or exposure studies on radon, biological agents, and chemicals were included. The main aim was to assess current knowledge on how energy saving measures and energy use can influence health. The included studies concluded that buildings classified as green buildings can improve health. More efficient heating and increased thermal insulation can improve health in homes experiencing fuel poverty. However, energy-saving measures in airtight buildings and thermal insulation without installation of mechanical ventilation can impair health. Energy efficiency retrofits can increase indoor radon which can cause lung cancer. Installation of a mechanical ventilation systems can solve many of the negative effects linked to airtight buildings and energy efficiency retrofits. However, higher ventilation flow can increase the indoor exposure to outdoor air pollutants in areas with high levels of outdoor air pollution. Finally, future research needs concerning energy aspects of buildings and health were identified.

1. Introduction

In modern society, people spend more than 90% of their time in indoor environments, and most of that time is spent at home [1]. Energy is needed to heat or cool buildings, and energy use in buildings is an important issue in contemporary society [2]. The climate change issue, linked to increased greenhouse gases emissions from coal, oil, or gas combustion, has increased the demand to save energy in buildings in different parts of the world [3]. Because of this demand, different measures have been applied to increase energy efficiency in buildings in order to create a sustainable built environment which combines a healthy and energy-efficient indoor environment [4].

There are three main principles of energy efficiency improvements in buildings: reduced energy use, reduced heat transfer, and reduced air leakage [5]. Reduced energy use can reduce emissions and fuel cost, thus reducing exposure to emissions [6]. Furthermore, reduced heat transfer can increase indoor temperature and reduce relative humidity and risk of mould [7]. In contrast, reduced air leakage can increase relative humidity and risk of mould [8]. In practice, common energy saving measures in buildings include increased thermal insulation, installation of central heating or space heating, draught proofing or installation of heat recovery systems [9]. Since energy use in buildings is a complex issue, scientists from many disciplines, as well as stake holders, government officers, and other decision makers need to work together to make updated energy policies [10].

In recent years, there has been an increase of energy-related labelling of buildings, e.g., low energy buildings, zero energy buildings, green buildings, and healthy buildings [11,12,13]. Green building rating systems have been widely used globally for many years [13]. In the USA, they have created Leadership in Energy and Environmental-Design (LEED) credits to assess green buildings [12]. Other existing green rating systems include BREEAM, CASBEE, Green Star, Enterprise Green Communities, RELi, SITES, Fitwel, Living Building Challenge (LBC), and WELL [11].

However, it should be realized that extreme cold in homes in winter can increase cold-related mortality or morbidity rates [14]. In the UK, fuel poverty is definite as people don’t have enough money to heat their home in winter to maintain an acceptable temperature [15]. However, there is also a cost for cooling their homes in extreme heat situations which some people cannot afford [16].

This systematic review included all types of health aspects of energy use, energy saving, and energy efficiency in buildings. The main aim was to summarize the current knowledge on the health impacts of energy saving measures and energy use. The second aim was to collect knowledge on the indoor environment effects of energy-saving measures and energy use. The third aim was to gather knowledge on types of energy saving or energy use that should be promoted from a health perspective.

2. Methods

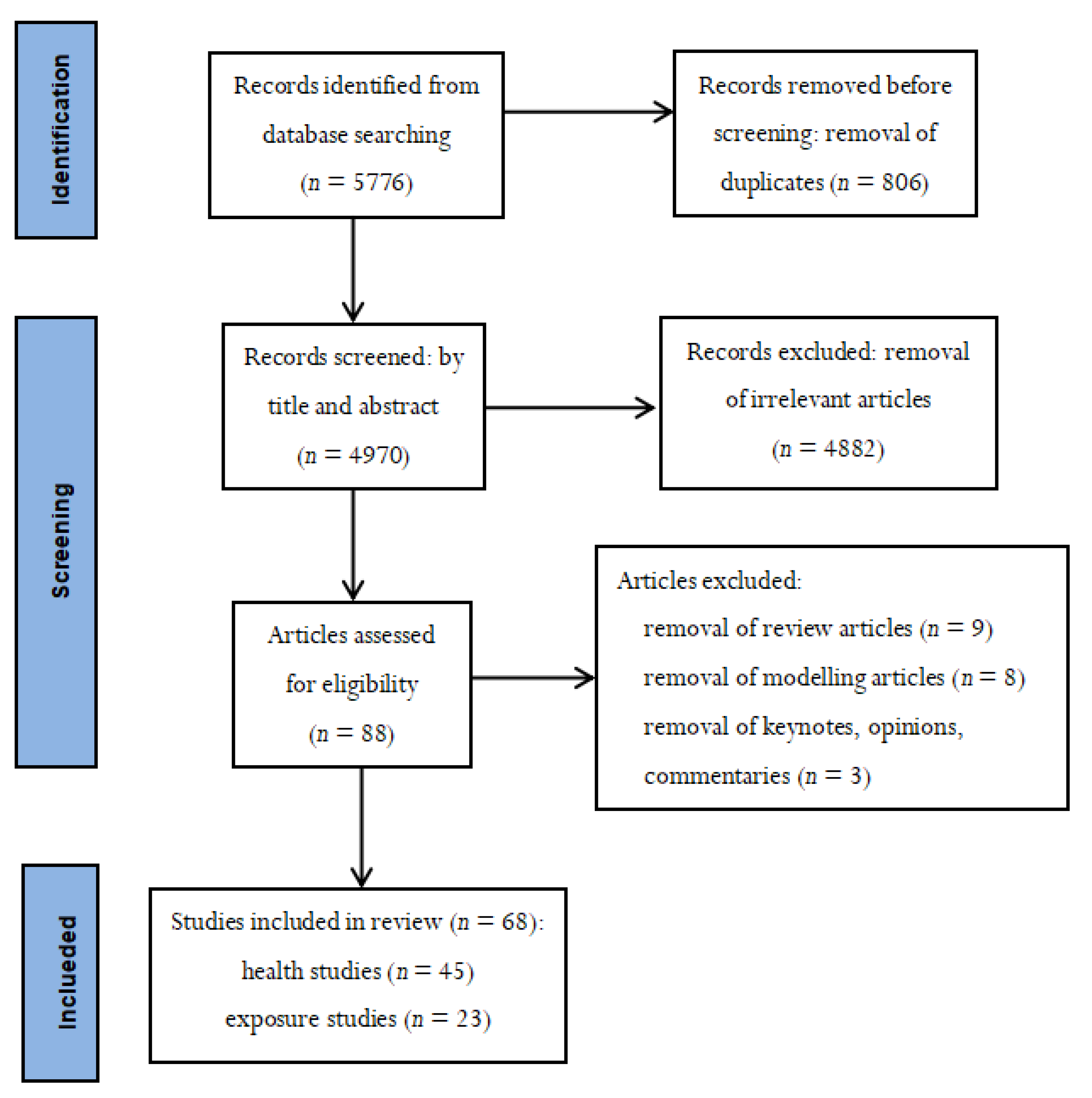

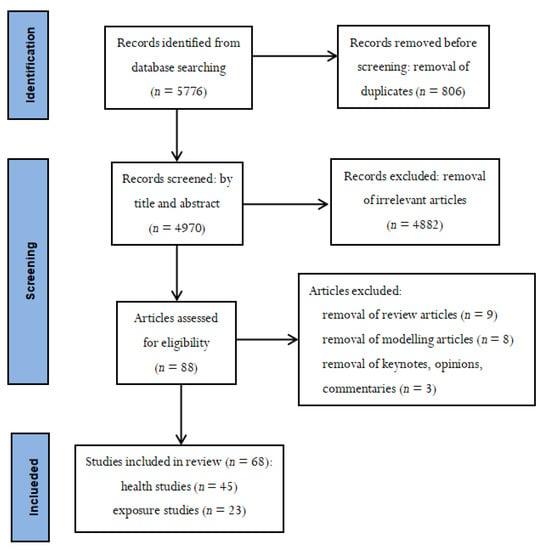

The guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement were followed to perform this systematic review [17]. In October 2020, a systematic literature search in PubMed covering articles up to 1 October 2020 was performed. There were ten medical search terms: morbidity, mortality, respiratory, lung function, asthma, rhinitis, eczema, dermatitis, sick building syndrome, building related illness. These medical search terms were combined (any of the ten search terms). In addition, there were eight energy and building related search terms: energy saving, energy use building, energy efficiency building, energy consumption building, energy efficient building, low energy building, energy retrofit, green building. These building and energy-related medical search terms were combined (any of the eight search terms). Then a systematic database search combining any of the ten medical search terms with any of the eight energy and building related search terms was performed. Any medical search term means OR between each search term. Any energy or building related search term means OR between each search term. Combined means AND between the two groups of search terms.

In total, 5776 records were identified from the database searching. Those records were sent to EndNote citation manager for collecting, storing, and organizing. In this reference management software, three reference groups (duplicated group, included group, excluded group) were created. First, 806 duplicated records were removed and added into duplicated group before screening by using the function of EndNote. Then the titles and the abstracts of 4970 articles were screened, to identify articles relevant to the topic of this literature review.

The following three selection criteria were used to include studies in this review:

- The articles should have studied associations between energy aspects in buildings and health;

- The articles should be written in English;

- The articles should not be keynotes, opinions, commentaries, reviews, or modelling studies.

In total, 4882 irrelevant articles were removed. After removal of irrelevant articles, 88 relevant articles were identified. As a next step, keynotes, opinions, commentaries, review articles and modelling articles were removed. Finally, 68 relevant field studies were included in this review, of which 45 were health studies and 23 studies had measured exposure in relation to energy aspects in buildings without investigating health associations. The PRISMA flow diagram of the literature research is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of literature research.

For each health study, study characteristics on author, year, country, energy aspects, type of study, type of buildings, type of health variables, number of buildings, number of subjects, and main results were extracted. For each exposure study, study characteristics on author, year, country, energy aspects, type of study, type of buildings, measured exposure, changes of measured exposure, number of households, or buildings and main results were extracted. In addition, within the health studies, articles with positive and negative health associations were grouped.

In order to further organize the structure of tables, a thematic classification was made. The studies were divided into four categories: exposure studies, green building health studies, fuel poverty health studies, other energy-related health studies. The exposure studies were divided into three exposure groups, including exposure to radon, exposure to biological agents (mould, bacteria, and house dust mites) and exposure to chemicals. The fuel poverty health studies were divided into three health aspects, including respiratory symptoms, general and mental health, and studies on mortality. Other energy-related health studies were divided into cross-sectional heath studies, longitudinal studies, and intervention health studies according to the study design. Details on those thematic tables can be seen in the Appendix A.

The entire process above involved at least two authors to conduct searching to gathering, screening, analyzing, and extracting.

3. Results

3.1. Exposure Studies

In Table 1, associations between energy-related building factors and indoor pollutants among the 23 included exposure studies are summarized. These included 19 studies conducted in Europe, 3 studies conducted in USA, and 1 study conducted in China. Except for one school study [18], 22 exposure studies were conducted in residential buildings (Appendix A).

Table 1.

Associations between energy-related building factors and pollutants among the 23 included exposure studies.

3.1.1. Radon

There were 11 exposure studies on radon [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] (Table A1). Of these, 9 studies reported that energy efficiency thermal retrofitting in homes increased radon concentration [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,29]. Of these 9 studies, 3 combined thermal insulation with additional air sealing methods in windows [21,22,27]. There were 6 studies of the 9, in five countries, which reported average radon concentrations above 100 Bq/m3 in rooms [19,20,22,24,25,27]. However, three studies of 11 demonstrated that energy efficiency retrofitting in homes with installation of mechanical ventilation or other measures can reduce radon concentration [26,27,28]. Other measures included installation of ground covers [26,27] and sub-slab or sump depressurization systems [26].

3.1.2. Biological Agents

There were 8 exposure studies on biological agents [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] (Table A2). One study reported that installation of insulated windows and central heating systems increased the concentration of the house dust mites and mould [30]. Another study showed that fuel poverty can increase indoor dampness and mould, regardless of the use of extractor fans [31]. The negative effects may be caused by reduced ventilation [30] and ineffective heating [31]. However, 6 studies of 8 found that energy efficiency improvement in homes with improved ventilation can reduce indoor exposure to mould [28,29,32,34], bacteria [29] and house dust mites [33].

3.1.3. Chemical Substances and Particles

There were 9 exposure studies on chemical substances and particles (Table A3). 4 studies demonstrated that home energy efficiency retrofit can increase indoor air concentrations of certain volatile organic compounds [29,36,38,39] and carbon dioxide levels (CO2) [39]. CO2 is an indicator of ventilation flow rate. Those volatile organic compounds included formaldehyde [38,39], aromatics [39], alkanes [39] and alpha-pinene [36], hexaldehyde [36], as well as benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, and xylene (BTEX) [29]. Alpha-pinene and hexaldehyde could be caused by the use of wood or wood-based products for construction and insulation [36]. However, some studies reported that home energy efficiency improvement combined with mechanical ventilation system can reduce aldehydes [28], formaldehyde [29], total volatile organic compounds (TVOC) [28], CO2 [18,28,37], carbon monoxide (CO) [27], and black carbon level [38]. One study found that an energy intervention replacing low-polluting semigasifier cooking stoves in rural buildings was associated with decreased exposures to 2.5 (PM2.5) particulate matter and black carbon in winter but higher exposure in summer. The negative effect could be caused by increased use of the cooking stove [40].

3.2. Health Studies

In Table 2, associations between one kind of fuel poverty, improved ventilation, and energy efficiency improvements and health are summarized. There were 28 studies which were conducted in Europe, 10 studies conducted in the USA, and 7 in other countries, including New Zealand (n = 3), Japan (n = 2), Canada (n = 1), and India, (n = 1). Except for three office [41,42,43] and three school studies [44,45,46], 39 studies were performed in residential buildings (Appendix A).

Table 2.

Associations between one kind of fuel poverty, improved ventilation, and energy efficiency improvements and health in all 45 selected health studies.

3.2.1. Green Building Health Studies

The green building health studies were conducted in United States (n = 5), Canada (n = 1), and India (n = 1). They were performed in two offices [41,42], two schools [44,45] and three residential buildings (Table A4). Some studies demonstrated that green buildings can reduce self-reported asthma [41,47,48], non-asthmatic respiratory symptoms [41,48], and improve general health [44,45,48,49] and mental health [41,49] as well as performance [41,44,45] and satisfaction [44,45]. One study found no significant association between green buildings and sick building syndrome symptoms (SBS) [42]. Sick building syndrome symptoms include nonspecific symptoms from eyes, skin, upper airways, headache, and fatigue [1].

3.2.2. Fuel Poverty Studies

The fuel poverty studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 10), the USA (n = 3), New Zealand (n = 3), Spain (n = 2), Japan (n = 1), and multiple countries (n = 1). All of the 20 studies were conducted in residential buildings (Table A5, Table A6 and Table A7). Some studies reported that fuel poverty in low-income homes can increase asthma [52] and respiratory symptoms [50,51] and reduce general health [57] and mental health [57]. Furthermore, low indoor air temperature in low-income homes can increase blood pressure [64,67] and hypertension [67] (linked to cold-related mortality). Besides, lack of insulation [65] and heating systems [68] in low-income homes can increase cold-related mortality. However, one study showed that wearable telemetry (a thermometer with a low-temperature alarm) can raise awareness of the health effects of cold living environments among people living in fuel poverty (linked to psychosocial outcomes) [63].

There were another some studies on the effects of improved ventilation or energy efficiency improvements in low-income homes and health. First, they found that high ventilation rates in low-income urban homes may increase chronic cough, asthma, and asthma-like symptoms, probably caused by infiltration of outdoor air pollutants [54]. However, high infiltration rates in low-income, urban, non-smoking homes can improve lung health [85]. Second, they demonstrated that installation of cavity wall insulation in social housing without installation of mechanical ventilation can reduce general health outcomes and social outcomes [53]. Energy efficient façade insulation retrofits in public housing can reduce cold-related mortality in women, but can increase cold-related mortality in men. The reason for the gender difference is unclear [66]. However, energy efficiency improvements in low-income homes can improve respiratory symptoms [53,55,56], general health [53,55,58,59,60] and mental health [53,58] as well as psychosocial outcomes [53,61,62], well-being [55,59,61,62], and sleep [58].

3.2.3. Cross-Sectional Health Studies

The cross-sectional health studies were conducted in Sweden (n = 4), the United Kingdom (n = 2), Norway (n = 1), and Germany (n = 1). Expect for one school study [46], seven studies were performed in residential buildings (Table A8). Some studies investigated the association between ventilation and health. They reported that higher ventilation rate in homes were associated with less asthma symptoms [72,73]. Furthermore, in multi-family buildings, lack of a mechanical ventilation system was associated with increased prevalence of SBS-related symptoms [69]. Further, buildings with balanced ventilation systems (supply/exhaust ventilation) had a higher prevalence of doctor diagnosed allergies, as compared to buildings with exhaust ventilation only [71].

There were some other investigative studies on the health impacts of energy efficiency in buildings. First, they found that air tightness [69,74] and use of direct electric radiators [69] in residential buildings were associated with increased prevalence of SBS-related symptoms. However, higher insulation level in buildings was associated with less SBS symptoms [70]. Second, buildings using more energy for heating were associated with lower rates of pollen allergies and eczema [71]. Energy efficiency improvements by boiler replacements in homes were associated with less admission rates for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [73]. Third, lower air temperature in buildings at a university campus was associated with less tear film stability [46]. Higher thermal variety (linked to lower domestic demand temperatures) was associated with fewer morbidities related to cold mortality [75].

3.2.4. Longitudinal Health Studies

A longitudinal study from Austria found that energy efficient buildings combined with installation of mechanical ventilation can improve general health and mental health but increase dry eye symptoms, as compared to conventional buildings with natural ventilation only [76] (Table A9).

3.2.5. Intervention Health Studies

Intervention health studies were conducted in the United Kingdom (n = 3), the United States (n = 2), Japan (n = 1), Sweden (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), and multiple countries (n = 1). Except for one office study [43], eight studies were performed in residential buildings (Table A10). Some studies reported that energy efficiency intervention in homes can improve asthma [77,78], respiratory symptoms [77,78,79,81], sinusitis [80], general health [80,83], satisfaction [80,81], and reduce blood pressure [84]. Furthermore, an improved mechanical ventilation rate in office buildings can improve SBS symptoms, productivity, and perceived indoor air quality [43]. In addition, energy saving by reducing ventilation flow to below 0.5 air change rate (ACH) could impair perceived air quality but did not influence SBS [82].

3.2.6. Energy Factors and Health

In Table 3, data on associations between energy factors and any health outcomes among all 45 selected health studies were summarized. Thermal issues, including fuel poverty or low indoor air temperature, were not included in this table. Most studies showed beneficial effects of energy saving.

Table 3.

Associations between energy factors and any health outcomes among all 45 selected health studies.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this review is the first systematic review on associations between different energy aspects of buildings and health. A meta-analysis could not be performed, since there were few articles covering the same energy aspect and the same health variable. However, the current knowledge level and knowledge gaps on the health effects of green buildings, fuel poverty, and energy use as well as energy efficiency improvements in buildings was able to be summarized or described.

In this review, there were three important issues related to exposure studies. Firstly, radon concentration in six studies was above 100 Bq/m3 in mean or in rooms [19,20,22,24,25,27]. In one review with meta-analysis on the risk of radon, the action level of radon for never-smokers and ever-smokers was recommended at 100 Bq/m3 of World Health Organization. They reported that radon exposure is the strongest risk factor for lung cancer for never-smokers [86]. Thus, special concern should be taken around radon exposure when performing home energy efficiency retrofits. In order to reduce radon levels in home energy-efficiency retrofits, installation of ground covers and sub-slab or sump depressurization systems as well as mechanical ventilation could be undertaken. One main source of indoor radon is radon from the ground. It should be ensured that the transmission of radon from the ground into buildings is minimized, especially for buildings in regions with primary geological layers in the underground. Another source of indoor radon is building materials, although it is not the main source. It is highly recommended that the building material for home retrofits works should meet the standards of green buildings. Secondly, installation of insulated windows and central heating systems can increase the indoor concentrations of mould [30]. The health risk of mould had been assessed in a previous review [8]. In many countries, mould and dampness caused by critical thermal bridges is a reason why energy efficiency interventions were performed [87]. Thus, it is important to consider thermal bridges as a cause of indoor mould growth after improving insulation in buildings. Thirdly, home energy efficiency retrofits can increase benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene, and xylene (BTEX) in indoor air [29]. In one previous review, the negative health effects of indoor BTEX had been reported [88]. Thus, it is important to use low-emissions building materials in energy efficiency retrofits.

Moreover, there were four important issues related to health studies.

Firstly, there were negative health effects in buildings with thermal insulation without installation of mechanical ventilation. In most cases, thermal insulation can reduce heat transfer, which will increase indoor temperature and reduce relative humidity and risk of mould. However, since many energy efficiency improvement methods can lead to reduced ventilation rates or air tightness, special concern should be taken to compensate for the reduced natural ventilation rate when working with home energy efficiency improvements. Thus, energy efficiency methods combined with improved ventilation or design should be promoted in airtight homes. In addition, the issue of thermal bridges and mould growth was seldom mentioned in the health studies.

Secondly, there were two negative associations between improved ventilation rate and health. In a fuel poverty study, high ventilation rates in low-income urban homes may increase chronic cough, asthma, and asthma-like symptoms [54]. This could be due to increased infiltration of outdoor air pollutants. Although this knowledge may be well known, the level of outdoor air pollutants had not been evaluated by the current intervention programs of low-income homes we found. In a cross-sectional health study, buildings with balanced ventilation systems (supply/exhaust ventilation) had a higher prevalence of doctor diagnosed allergies, as compared to buildings with exhaust ventilation only [71]. This may be caused by lack of a correct replacement of dirty filters in balanced mechanical ventilation systems. Thus, this knowledge should be addressed to residents in homes with energy efficiency improvements combined with balanced ventilation systems.

Thirdly, four fuel poverty health studies on cold mortality were performed in a longitudinal study design. This means that the cold-mortality effect of fuel poverty has been well known. Thus, fuel poverty behavior should be considered in interventions since it is often linked to reduced ventilation rate and ineffective heating. Except for winter fuel payment and energy intervention policy, wearable telemetry may be a good choice of solution in cold homes [63]. This is because wearable telemetry can increase the occupant’s awareness of cold. However, all those studies were based on cold climates. In hot climate zones, there is a need to conduct similar research in low-income homes.

Fourthly, 4 green buildings health studies were conducted in a longitudinal study design. This means that long-term health effects of green buildings were assessed in the USA. However, those green buildings were assessed by LEED credits of the USA standard. Although there are existing green rating systems in different countries, energy efficiency improvements combined with correct ventilation and renewable energy use have been emphasized in most green rating systems.

This literature review has a number of strengths. The main focus was on epidemiological studies, including intervention studies, cross-sectional studies, and longitudinal studies. However, exposure studies without any reported health data or health associations were also included if they were identified in this literature search. For each included study, the country of the study, type of study, type of buildings, number of buildings and number of subjects were noted in the review. In exposure studies, extra information on the changes of concentrations of major pollutants was collected. In studies with unexpected results or negative impacts of energy use and energy saving, explanations of the results reported by the authors were included.

The studies included in this review had some limitations in their study design. One major limitation was that none of the studies had studied health effects of energy efficiency improvement by the installation of heat recovery to existing mechanical ventilation systems. This may be because many studies had not separated it from combined energy efficiency measures. However, installation of heat recovery to mechanical ventilation systems is a major method nowadays to save energy use and there is a need to assess its health benefits, especially in airtight homes. The second limitation is that many of the intervention studies were based on more than two energy saving improvements. Thus, it is not possible to draw clear conclusions on the health effects of single energy efficiency improvement measures. The third limitation is that there were few prospective health studies on long-term health effects of energy efficiency improvements and energy use. However, many prospective health studies on green buildings and fuel poverty were found. The fourth limitation is that most studies were on residential buildings. Only three studies were on office buildings and only four studies were on school or university buildings.

5. Conclusions

Energy efficiency improvements and green building can have positive effects on asthma, respiratory symptoms, mental health, and general health as well as on performance and satisfaction. Home energy efficiency improvement with mechanical ventilation system can reduce radon, mould, bacteria, and house dust mites, TVOC, CO2, CO, and black carbon levels as well as some volatile organic compounds. More efficient heating and increased thermal insulation can have positive health impacts in fuel-poverty homes. However, energy savings in airtight buildings and thermal insulation without the installation of mechanical ventilation can impair health. Moreover, health risks linked to energy efficiency retrofits exists. Installation of mechanical ventilation can solve many of the negative effects linked to airtight buildings and energy efficiency retrofits.

For future energy efficiency intervention or retrofit studies, measures of radon and BTEX and other chemicals, as well as levels of thermal bridge and outdoor air pollutants may be needed. In addition, it is important to replace dirty filters in balanced mechanical ventilation systems.

Furthermore, future research needs on this topic were identified. Firstly, the intervention study should measure how much energy they save after energy efficiency measures. Secondly, more studies are needed on the health aspects of energy efficiency improvement by the installation of heat recovery to mechanical ventilation system. Thirdly, future studies should focus on evaluating health effects of single energy efficiency improvement measures, rather than a combination of measures. Fourthly, more prospective health studies on long-term health effects of energy efficiency improvements or energy use are needed. Fifthly, future studies should include offices, schools, and hospital buildings, and should cover different climate zones in the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W., J.W. and D.N.; Methodology, C.W., J.W. and D.N.; Data Curation, C.W., J.W. and D.N.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.W.; Writing—Review & Editing, C.W., J.W. and D.N.; Supervision, J.W. and D.N.; Funding Acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Swedish AFA Insurance (No. 467801100).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Exposure Field Studies on Radon.

Table A1.

Exposure Field Studies on Radon.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Measured Exposure | Changes of Measured Exposure | Number of Households or Buildings | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collignan et al. [19] | 2016 | France | Improved insulation, ventilation and window replacement | One time measurement | Residential buildings | Radon | 21% increase (median 147 Bq/m3) | 3233 households or 3233 buildings | Energy efficiency thermal retrofit (linked to reduced air permeability of the building envelope) can increase indoor radon concentration. |

| Symonds et al. [20] | 2019 | United Kingdom | Insulation in loft and wall, double glazing | Longitudinal | Residential buildings | Radon | Arith. Mean > 132–159.3 Bq/m3− | 470,689 households | Energy efficiency retrofit by improving insulation in loft and wall, and/or double glazing can increase radon concentrations, possibly due to increased airtightness. |

| Du et al. [29] | 2019 | Finland and Lithuania | Improved insulation in wall, roof, windows or balconies | Intervention | Residential buildings | Radon | Mean increase of 13.8 Bq/m3 (<100 Bq/m3) | 336 households or 65 buildings | In homes in Lithuania, energy efficiency retrofits without installation of mechanical ventilation increased indoor radon concentrations. |

| Pigg et al. [27] | 2018 | United States | Weatherization services | Intervention | Residential buildings | Radon | Increased by 0.14 ± 0.13 pCi/L (>100 Bq/m3 in high zone) | 514 households | Energy efficiency weatherization services (retrofits) can increase radon concentration. However, energy efficiency weatherization services with improved ventilation or ground covers can reduce radon concentration. |

| Meyer et al. [21] | 2019 | Germany | Air tightness windows and insulation of outer walls | One time measurement | Residential buildings | Radon | 40 Bq/m3 in non-refurbished vs. 69 Bq/m3 in refurbished | 150 households | Energy efficiency refurbishments of existing buildings without installation of ventilation systems can increase radon concentration, as compared to non-refurbished conventional buildings. |

| Pressyanov et al. [22] | 2015 | Bulgaria | New energy-efficient windows with plastic joinery | Intervention | Residential buildings | Radon | Rooms with radon increase was 193 Bq/m3 and rooms with no change was 45 Bq/m3 | 20 rooms or 16 buildings | Energy-efficient reconstructions with installation of new energy-efficient windows (linked to air tightness) can increase radon levels. |

| Vasilyev et al. [23] | 2017 | Russia | Energy efficiency insulation | One time measurement | Residential buildings | Radon | Arithmetic mean 38 Bq/m3 in conventional vs. 93 Bq/m3 in modern buildings | 81 buildings | Energy efficiency measures in buildings (linked to low indoor air exchange rate) can increase indoor radon concentration. |

| Yarmoshenko et al. [24] | 2014 | Russia | Energy efficiency insulation | Before-after | Residential buildings | Radon | Arithmetic mean 42 Bq/m3 in conventional vs. 133 Bq/m3 in modern buildings | 7 households or 7 buildings | Energy efficiency measures in buildings (linked to low indoor air exchange rate) can increase indoor radon concentration. |

| Vasilyev et al. [25] | 2015 | Russia | Energy efficiency insulation | Before-after | Residential buildings | Radon | Arithmetic mean 42 Bq/m3 in conventional vs. 166 Bq/m3 in modern buildings | 5 rooms or 5 buildings | Energy efficiency measures in buildings (linked to low indoor air exchange rate) can increase indoor radon concentration. |

| Burghele et al. [26] | 2020 | Romania | Installation of centralized and decentralized mechanical ventilation with heat recovery | Intervention | Residential buildings | Radon | Reduction was between 25% to 95% (Before >100 Bq/m3) | 10 households or 10 buildings | Sub-slab and sump depressurization, installation of centralized and decentralized mechanical ventilation with heat recovery can reduce radon concentrations. |

| Wallner et al. [28] | 2015 | Austria | Existing mechanical ventilation and natural ventilation | Before-after | Residential buildings | Radon | 17 Bq/m3 mechanical ventilation vs. 31 Bq/m3 natural ventilation | 123 households | Energy-efficient buildings with existing mechanical ventilation can reduce radon concentrations, as compared to conventional buildings without installation of mechanical ventilation, especially for radon. |

Table A2.

Exposure Field Studies on Mould Bacteria and House Dust Mites.

Table A2.

Exposure Field Studies on Mould Bacteria and House Dust Mites.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Measured Exposure | Changes of Measured Exposure | Number of Households | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hirsch et al. [30] | 2000 | Germany | Installation of insulated windows and central heating systems | Intervention | Residential buildings | House dust mite Der f 1 and mould | Der f 1 in carpets 0.65 vs. 1.28, mattresses 1.56 vs. 2.40 μg/g; Aspergillus fumigatus 20 vs. 60 units/g | 98 households | Installation of insulated windows and central heating systems (linked to reduced ventilation) increased the concentration of the house dust mite allergen Der f 1 and the mould species Aspergillus fumigatus. |

| Sharpe et al. [31] | 2015 | United Kingdom | Fuel poverty | Cross-sectional | Social Residential buildings | Self-reported dampness and mould | No data | 671 households | Fuel poverty (linked to ineffective heating and ventilation practices) can increase indoor dampness and mould, regardless of the use of extractor fans. |

| Sharpe et al. [32] | 2016 | United Kingdom | Type of heating, glazing, insulation levels, energy efficiency ratings | Cross-sectional | Social Residential buildings | Self-reported allergenic mould | No data | 41 households | Energy efficiency improvement combined with increased ventilation flow rate reduced fungal contamination with Aspergillus/Penicillium mould species and Cladosporium spp. |

| Spertini et al. [33] | 2010 | Switzerland | Improved insulation, ventilation system with heat recovery and natural ventilation | One time measurement | Residential buildings | Self-reported house dust mites Der f 1 | Median 67 vs. 954 ng/g in mattresses and 20 vs. 174 ng/g in carpets | 289 households or 11 buildings | Buildings designed for low energy use with installation of mechanical ventilation reduced indoor relative air humidity as well as house dust mite allergen concentration both in mattresses and in carpets, as compared to control buildings. |

| Niculita-Hirzel et al. [34] | 2020 | Switzerland | Type of ventilation and energy consumption | One time measurement | Residential buildings | Fungal | Penicillium CFUs was lower | 149 households | Installation of mechanical ventilation in buildings reduced the infiltration of outdoor fungal particles, as compared to buildings with natural ventilation only. |

| Coombs et al. [35] | 2018 | United States | Green renovation with bathroom fans | Before-after | Residential buildings | Mould | 521,826 reads from green homes vs. 726,690 fungal reads from non-green homes | 52 households | The concentration of mould in air samples and door dust samples did not differ between green and non-green homes. However, green homes had a lower concentration of mould in bed samples. |

| Du et al. [29] | 2019 | Finland and Lithuania | Replacing windows and/or installation of heat recovery to the existing exhaust ventilation system | Intervention | Residential buildings | Airborne mould and bacterial | Fungal 0.6-log; Bacterial 0.6-log in gram-positive and 0.9-log in gram-negative bacterial (reduction in cells/m2) | 336 households or 65 buildings | In homes in Finland, energy efficiency retrofits with installation of mechanical ventilation reduced indoor concentrations of airborne mould and bacterial. |

| Wallner et al. [28] | 2015 | Austria | Mechanical ventilation and natural ventilation | Before-after | Residential buildings | Mould | 84% of rooms vs. 35% rooms | 123 households | Energy-efficient buildings with installation of mechanical ventilation reduced indoor mold spore concentration, as compared to conventional buildings without installation of mechanical ventilation. |

Table A3.

Exposure Field Studies on Chemicals.

Table A3.

Exposure Field Studies on Chemicals.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Measured Exposure | Changes of Measured Exposure | Number of Households or Buildings | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derbez et al. [36] | 2018 | France | Installation of ventilation system or passive stack/hybrid ventilation | Before-after | Residential buildings | VOCs, aldehyde | Hexaldehyde: 37 vs. 17 µg/m3 in dwellings with/without flooring products | 72 households or 43 buildings | Low energy retrofit can increase the air concentration of alpha-pinene and hexaldehyde, possibly caused by the use of wood or wood-based products for the construction and insulation. |

| Du et al. [29] | 2019 | Finland and Lithuania | Replacing windows and/or installation of heat recovery to the existing exhaust ventilation system | Intervention | Residential buildings | BTEX and formaldehyde | Mean increase of 2.5 µg/m3 in BTEX | 336 households or 65 buildings | In homes in Finland, energy efficiency retrofits with existing mechanical ventilation increased indoor air concentrations of benzene, toluene, ethyl benzene and xylene (BTEX) but reduced indoor formaldehyde concentrations. |

| Leivo et al. [37] | 2018 | Finland and Lithuania | Installation of heat recovery to the existing exhaust ventilation system. Improved thermal insulation in wall, roof, windows or balconies | Intervention | Residential buildings | CO2 | Median: 775 vs. 956 PPM (1st); Median: 730 vs. 840 PPM (2nd) | 290 households or 66 buildings | In homes in Finland, energy efficiency retrofits with existing mechanical ventilation reduced CO2 concentration as compared to natural ventilation. In homes in Lithuania, improved insulation without installation of mechanical ventilation increased measured CO2 levels. |

| Coombs et al. [38] | 2016 | United States | Green renovation | Intervention | Residential buildings | Black carbon, formaldehyde | Black carbon averaging 682 vs. 2364 ng/m3; Formaldehyde 0.03 vs. 0.01 ppm | 42 households | Energy efficiency green renovation (linked to reduced ventilation) decreased indoor black carbon level in air from outdoor sources and increased indoor formaldehyde concentration. |

| Yang et al. [39] | 2020 | Switzerland | Thermal retrofit of roof, walls and floors, replacement of heating system, installation of mechanical ventilation system | One time measurement | Residential buildings | Aldehydes, VOCs | Formaldehyde 13 vs. 15; Toluene 16 vs. 26; Xylenes 1.4 vs. 5.8; Acrolein 0.4 vs. 0.6; D-limonene 7.9 vs. 11; Isobutane 3.4 vs. 10; Butane 8.8 vs. 2 (µg/m3) | 169 households | Energy efficiency thermal retrofit without installation of mechanical ventilation increased formaldehyde, aromatics, alkane, and levels of certain volatile organic compounds, as compared to new homes built with installed mechanical ventilation. |

| Verriele et al. [18] | 2016 | France | Controlled ventilation systems | Before-after | School buildings | CO2 | Peak Level 1000 ppm vs. 3800–5000 ppm | 10 school buildings | Low energy school buildings combined controlled mechanical ventilation systems and an adapted ventilation schedule can reduce CO2 levels. |

| Pigg et al. [27] | 2018 | United States | Weatherization services | Intervention | Residential buildings | CO | Peak Level 35 ppm vs. 13–20 ppm | 514 households | Energy efficiency weatherization services in homes without improved ventilation or ground covers can reduce exposure to CO. |

| Wallner et al. [28] | 2015 | Austria | Mechanical ventilation and natural ventilation | Before-after | Residential buildings | CO2, TVOC, aldehydes | CO2: 1360 vs. 1830 ppm and 1280 vs. 1740 ppm; TVOC: 300 vs. 560 µg/m3; aldehydes: 32 vs. 53 µg/m3 and 18 vs. 33 µg/m3 | 123 households | Energy efficient buildings with installation of mechanical ventilation reduced indoor concentrations of CO2, TVOC, aldehydes, and improved the measured indoor air quality in homes, as compared to conventional buildings without installation of mechanical ventilation. |

| Baumgartner et al. [40] | 2019 | China | Low-polluting semi gasifier cook stove with chimney, water heater and pelletized biomass fuel | Intervention | Residential buildings | PM2.5, black carbon | PM2.5 (46%), black carbon (55%) | 205 households | An energy intervention replacing low-polluting semi gasifier cook stove in rural buildings was associated with decreased exposures to PM2.5 and black carbon in winter but higher exposures to PM2.5 and black carbon in summer, as compared to untreated homes with traditional stoves. The negative effect could be caused by increased use of semi gasifier cook stove. |

Table A4.

Green Building Health Studies.

Table A4.

Green Building Health Studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Type of Health Variables | Number of Buildings | Number of Subjects | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Garland et al. [47] | 2013 | United States | Green buildings with LEED Credits | Intervention | Residential buildings | Self-reported asthma | 1 building | 18 children and adults | Green home buildings can reduce self-reported asthma symptoms. |

| Singh et al. [41] | 2010 | United States | Green buildings with LEED Credits | Longitudinal | Office buildings | Absenteeism due to self-reported asthma, respiratory allergies, depression and stress, and work productivity | 2 office buildings | 263 employees | Green office buildings can improve indoor environment quality and reduce absenteeism due to self-reported asthma, respiratory allergies, depression and stress, and moreover improve work productivity. |

| Breysse et al. [48] | 2011 | United States | Green efficiency renovation | Longitudinal | Residential buildings | Self-reported asthma, and non-asthma respiratory problems, overall health | 1 building | 80 children and adults | Among adults, green efficiency renovation in homes can reduce self-reported asthma. Green efficiency renovation in homes can improve self-reported overall health and reduce non-asthmatic respiratory symptoms in adults as well as in children. |

| Breysse et al. [49] | 2015 | United States | Green efficiency renovation | Intervention | Residential buildings | Self-reported mental and general physical health | 1 building | 612 older adults | Green efficiency renovation in homes can improve mental and general physical health. |

| Hedge et al. [44] | 2013 | United States | Green buildings with LEED Credits | Longitudinal | University buildings | Overall health, performance and work satisfaction | 2 university buildings | 44 employees | Green office buildings in a college campus improved health, performance and work satisfaction. |

| Hedge et al. [45] | 2014 | Canada | Green buildings with LEED Credits | Longitudinal | University buildings | Overall health, performance and study satisfaction | 3 university buildings | 319 employees | Green classrooms in an university campus improved health, performance and work satisfaction. |

| Gawande et al. [42] | 2020 | India | Green Office Buildings | cross-sectional | Office Buildings | SBS | 10 office buildings | 148 employees | No significant association between green buildings and sick building syndrome symptoms (SBS), compared with conventional buildings. |

Table A5.

Fuel Poverty Health Studies on Respiratory Symptoms.

Table A5.

Fuel Poverty Health Studies on Respiratory Symptoms.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Type of Health Variables | Number of Households | Number of Subjects | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rudge et al. [50] | 2005 | United Kingdom | Fuel poverty | Longitudinal | Residential buildings | Winter respiratory disease | 220 households | 460 older adults | Fuel poverty in low-income homes can increase winter respiratory disease. |

| Webb et al. [51] | 2013 | United Kingdom | Fuel poverty | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Measured respiratory disease | 3763 households | 3763 older adults | Fuel poverty in low-income homes increase respiratory disease. |

| Sharpe et al. [52] | 2015 | United Kingdom | Type of heating, glazing, insulation, energy efficiency ratings | Cross-sectional | Social residential buildings | Doctor diagnosed asthma | 706 households | 944 adults | Energy efficiency improvement in social housing might increase current adult asthma. This may be due to increased exposure to physical, biological and chemical contaminants linked to inadequate heating, ventilation (fuel poverty behavior). |

| Poortinga et al. [53] | 2017 | United Kingdom | Loft insulation, cavity-wall insulation, external wall insulation | Repeated cross-sectional | Social residential buildings | General health, mental health, and social outcomes | Around 9200 households | 10,009 individuals | Energy efficiency improvements in social housing can improve respiratory symptoms. |

| Carlton et al. [54] | 2019 | United States | Home ventilation rate | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Respiratory symptoms | 216 households | 302 children and adults | High ventilation rates in low-income urban homes may increase chronic cough, asthma and asthma-like symptoms, probably caused by infiltration of outdoor air pollutants. |

| Howden-Chapman et al. [55] | 2011 | New Zealand | Improved insulation into existing houses; more effective heating in insulated houses | Intervention | Residential buildings | Respiratory symptoms | 1350 households; 409 households | 4407 children and adults; 409 children | Energy saving by using more effective heating in insulated low-income homes can improve health status and respiratory symptoms in children with asthma diagnosis. |

| Howden-Chapman et al. [56] | 2007 | New Zealand | Installation of a standard retrofit insulation package | Intervention | Residential buildings | Hospital admissions for respiratory conditions | 1350 households | 4407 children and adults | Energy saving by insulating existing houses in low-income communities can improve indoor environment and reduce hospital admissions for respiratory conditions. |

| Humphrey et al. [85] | 2020 | United States | Home ventilation rate | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Measured lung function | 187 households | 253 children and adults | High infiltration rate in low-income, urban, non-smoking homes can improve lung health. |

Table A6.

Fuel Poverty Health Studies on General and Mental Health.

Table A6.

Fuel Poverty Health Studies on General and Mental Health.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Type of Health Variables | Number of Households | Number of Subjects | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomson et al. [57] | 2017 | 32 European Countries | Fuel poverty | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | General health and well-being | No data | 41,560 adults | Fuel poverty in low-income homes can reduce general health and emotional well-being. |

| Poortinga et al. [53] | 2017 | United Kingdom | Loft insulation, cavity-wall insulation, external wall insulation | Repeated cross-sectional | Social residential buildings | General health, mental health, and social outcomes | Around 9200 households | 10,009 individuals | Energy efficiency improvements in social housing can improve general health, mental health and social outcomes. However, installation of cavity wall insulation without installation of mechanical ventilation can reduce general health outcomes and social outcomes. |

| Ahrentzen et al. [58] | 2016 | United States | Insulation of roof and floor, improved thermal, air conditioner heating, cooling system, new ceiling fans, new windows | Intervention | Residential buildings | General health, emotional distress, sleep | 53 households | 57 older adults | Energy efficiency retrofits in low-income homes can improve general health, emotional distress, and sleep among the older adults. |

| Shortt et al. [59] | 2007 | United Kingdom | Installation of central heating systems or improved insulation | Intervention | Residential buildings | General health, well being | 100 households | 100 individuals | Energy efficiency intervention in fuel poverty homes can improve general health, well-being. |

| Howden-Chapman et al. [55] | 2011 | New Zealand | Improved insulation into existing houses; more effective heating in insulated houses | Intervention | Residential buildings | General health and well being | 1350 households; 409 households | 4407 children and adults; 409 children | Energy saving by improving insulation in low-income homes can improve general health and well-being and reduce hospitalization in children and adults. Energy saving by using more effective heating in insulated low-income homes can improve general health status in children. |

| Howden-Chapman et al. [56] | 2007 | New Zealand | Installation of a standard retrofit insulation package | Intervention | Residential buildings | General health and well being | 1350 households | 4407 children and adults | Energy saving by insulating existing houses in low-income communities can improve indoor environment so that improve self-reported health, wheezing, days off school and work. |

| Chapman et al. [60] | 2009 | New Zealand | Installation of a standard retrofit insulation package | Intervention | Residential buildings | General health, well being | 1350 households | 4407 children and adults | Energy saving by insulating existing houses in low-income communities can improve general health, as well as cost-benefit of general practitioner (GP) visits, hospitalizations, reduced time off work and school. |

| Grey et al. [61] | 2017 | United Kingdom | External wall insulation, central heating system, and installation of gas network | Intervention | Residential buildings | Well-being and psychosocial outcomes | 774 households | 776 individuals | Energy efficiency intervention in low-income homes can increase residential wellbeing and psychosocial-related health. |

| Poortinga et al. [62] | 2018 | United Kingdom | External wall insulation, photovoltaics, solar water heating, air source heat pumps, loft/rafter insulation | Intervention | Residential buildings | Well-being and psychosocial outcomes | 4968 households | 25,908 individuals | Energy efficiency intervention in low-income homes can improve well-being and psychosocial outcomes. |

| Pollard et al. [63] | 2019 | United Kingdom | Fuel poverty | Intervention | Residential buildings | Psychosocial outcomes | 22 households | 22 adults | Wearable telemetry (a thermometer with a low-temperature alarm) can raise awareness of the health effects of cold home among people living in fuel poverty (linked to psychosocial outcomes). |

Table A7.

Fuel Poverty Health Studies on Cold-related Mortality.

Table A7.

Fuel Poverty Health Studies on Cold-related Mortality.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Type of Health Variables | Number of Households | Number of Subjects | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angelini et al. [64] | 2019 | United Kingdom | Winter fuel payment | Longitudinal | Residential buildings | Cold-related mortality, blood pressure, fibrinogen | 11,578 households | 18,813 adults | Low indoor air temperature in low-income homes can increase systolic and diastolic blood pressure and fibrinogen levels in blood samples (linked to cold-related mortality). |

| Sartini et al. [65] | 2018 | United Kingdom | Fuel poverty, types of home insulation and heating | Longitudinal | Residential buildings | Cold-related mortality | 1006 households | 1402 older men | Lack of insulation in low-income homes can increase cold-related mortality. |

| Peralta et al. [66] | 2017 | Spain | Energy efficient façade insulation retrofit | Longitudinal | Social residential buildings | Cold-related mortality | 2552 households | 2552 individuals | Energy efficient façade insulation retrofit in public housing can reduce cold-related mortality in women, but can increase cold-related total mortality in men. The health outcome for the gender difference is unclear. |

| Umishio et al. [67] | 2019 | Japan | Low insulation in cold homes | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Blood pressure | 1840 households | 2900 adults | Low indoor air temperature was higher associated with blood pressure and hypertension (linked to cold-related mortality). |

| López-Bueno et al. [68] | 2020 | Spain | Heating systems | Longitudinal | Residential buildings | Cold-related mortality | No data | No data | Districts with higher homes without a heating system had cold-related mortality. |

Table A8.

Cross-sectional Health Studies.

Table A8.

Cross-sectional Health Studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Type of Health Variables | Number of Buildings or Households | Number of Subjects | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engvall et al. [69] | 2003 | Sweden | Type of ventilation and heating system, heat pumps, reconstruction and energy-saving measures | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Sick building syndrome (SBS) symptoms | 231 buildings | 3241 adults | In multi-family buildings, lack of a mechanical ventilation system and use of direct electric radiators were associated with increased prevalence of SBS-related symptoms. Major reconstruction and multiple sealing in multi-family buildings were associated with increased prevalence of SBS-related symptoms. |

| Smedje et al. [70] | 2017 | Sweden | Type of ventilation system and insulation level | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Sick building syndrome (SBS) symptoms | 605 buildings | 1160 adults | In single-family buildings, a lower U-value (higher insulation level) was associated with less SBS symptoms. |

| Norback et al. [71] | 2014 | Sweden | Type of ventilation and energy use for heating | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Doctor’s diagnosed asthma, allergy and self-reported pollen allergy, eczema | 472 buildings | 7554 adult | Multi-family buildings with balanced ventilation systems (supply/exhaust ventilation) had a higher prevalence of doctor diagnosed allergy, as compared to buildings with exhaust ventilation only. Buildings using more energy for heating were associated with less pollen allergy and eczema. |

| Wang et al. [72] | 2017 | Sweden | Type of ventilation and degree of insulation | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Doctors’ diagnosed asthma, self-reported asthma | 605 buildings | 1160 adults | Higher air exchange rate in the single-family residential homes was associated with less current asthma symptoms. |

| Sharpe et al. [73] | 2019 | United Kingdom | Energy efficiency ratings | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease | No data | No data | Reduced home ventilation rates were associated with more asthma disease. Homes with more energy efficiency improvements may were associated with more admission rates for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, possibly caused by reduced home ventilation flow rate. Energy efficiency measures can improve health outcomes, especially chronic respiratory illness. |

| Sobottka et al. [74] | 1996 | Germany | New windows and door, improved insulation and heating system | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Sick building syndrome (SBS) symptoms | 52 buildings | No data | Energy saving by installing new air tightness windows and door in homes was associated with more SBS-related health complaints. This may be due to fuel poverty behavior by not airing their flats sufficiently. |

| Bakke et al. [46] | 2008 | Norway | Lower air temperature | Cross-sectional | University buildings | Tear film stability, nasal patency | 4 university buildings | 173 employees | Lower air temperature in buildings at a university campus was associated with less tear film stability and more health problems. |

| Kennard et al. [75] | 2020 | United Kingdom | Space heating energy use | Cross-sectional | Residential buildings | Cold-mortality | 77,762 households | 77,762 adults | Higher thermal variety (linked to lower domestic demand temperatures) was associated with less morbidities related to cold-mortality. |

Table A9.

Longitudinal Health Studies.

Table A9.

Longitudinal Health Studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Type of Health Variables | Number of Buildings | Number of Subjects | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wallner et al. [76] | 2017 | Austria | Mechanical ventilation and natural ventilation | Longitudinal | Residential buildings | General health and dry eye symptoms | 123 buildings | 575 children and adults | Energy efficient buildings combined with installation of mechanical ventilation can improve self-reported health but increase dry eye symptoms, as compared to conventional buildings with natural ventilation only. |

Table A10.

Intervention Health Studies.

Table A10.

Intervention Health Studies.

| Author | Year | Country | Energy Aspects | Type of Study | Type of Buildings | Type of Health Variables | Number of Buildings or Households | Number of Subjects | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somerville et al. [77] | 2000 | United Kingdom | the installation of central heating systems | Intervention | Residential buildings | Respiratory symptoms | 59 households | 72 children with diagnosed asthma | Energy efficiency intervention in homes reduced respiratory symptoms, and reduced missed school days due to asthma in children with diagnosed asthma. |

| Barton et al. [78] | 2007 | United Kingdom | Central heating systems, ventilation, rewiring, insulation, and re-roofing | Intervention | Social residential buildings | Asthma, non-asthma-related respiratory disease | 119 households | 480 children and adults | Energy efficiency intervention in social housing reduced asthma symptoms, and non-asthmatic respiratory disease. |

| Osman et al. [79] | 2010 | United Kingdom | Central heating systems, installation of loft, under-floor and cavity wall insulation | Intervention | Residential buildings | Diagnosed chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 178 households | 178 older adults with COPD | Energy efficiency intervention in homes can improve respiratory health for elderly COPD patients. |

| Wilson et al. [80] | 2013 | United States | Insulation, heating equipment and ventilation improvements | Intervention | Residential buildings | Sinusitis, general health, satisfaction | 248 households | 323 children and adults | Energy efficiency retrofits work in homes can improve sinusitis, general health, satisfaction. |

| Haverinen-Shaughnessy et al. [81] | 2018 | Finland and Lithuania | Installation of heat recovery to the existing exhaust ventilation system. Improved thermal insulation in wall, roof, windows or balconies | Intervention | Residential buildings | Respiratory symptoms | 66 buildings | 283 individuals | Energy efficiency retrofits in homes can improve occupant satisfaction with daily noise nuisance, upper respiratory symptoms, and reduce absence from school or from work due to respiratory infections. |

| Wargocki et al. [43] | 2000 | Denmark | different ventilation rates | Intervention | Office building | Sick building syndrome (SBS) symptoms, work productivity | 1 office building | 30 female employees | Improved mechanical ventilation rate in office building improve SBS symptoms, work productivity, and perceived indoor air quality. |

| Engvall et al. [82] | 2005 | Sweden | different ventilation rates | Intervention | Residential buildings | General health | 1 building | 44 adults | Energy saving by reducing ventilation flow to below 0.5 ACH could impair perceived air quality but did not influence SBS. |

| Francisco et al. [83] | 2017 | United States | Weatherization services | Intervention | Residential buildings | General health | 72 households | 178 children and adults | Energy efficiency retrofits can improve self-reported health. |

| Umishio et al. [84] | 2020 | Japan | installation of outer walls, floor and/or roof insulation and replacement of windows | Intervention | Residential buildings | Blood pressure | 1009 households | 1685 adults | Energy efficiency insulation retrofitting in homes can reduce home blood pressure and reduce morning home systolic blood pressure of hypertensive patients. |

References

- Norbäck, D. An update on sick building syndrome. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 9, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melikov, A.K. Advanced air distribution: Improving health and comfort while reducing energy use. Indoor Air 2016, 26, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smith, K.R.; Frumkin, H.; Balakrishnan, K.; Butler, C.D.; Chafe, Z.A.; Fairlie, I.; Kinney, P.; Kjellstrom, T.; Mauzerall, D.L.; McKone, T.E.; et al. Energy and human health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 159–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brennan, M.; O’Shea, P.M.; Mulkerrin, E.C. Preventative strategies and interventions to improve outcomes during heatwaves. Age Ageing 2020, 49, 729–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willand, N.; Ridley, I.; Maller, C. Towards explaining the health impacts of residential energy efficiency interventions—A realist review. Part 1: Pathways. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 133, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.; Charles, J.W.; Temte, J.L. Climate change, human health, and epidemiological transition. Prev. Med. 2015, 70, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilkinson, P.; Smith, K.R.; Beevers, S.; Tonne, C.; Oreszczyn, T. Energy, energy efficiency, and the built environment. Lancet 2007, 370, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peat, J.K.; Dickerson, J.; Li, J. Effects of damp and mould in the home on respiratory health: A review of the literature. Allergy 1998, 53, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolokotsa, D.; Santamouris, M. Review of the indoor environmental quality and energy consumption studies for low income households in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 536, 316–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, L.; Prestwood, E.; Marsh, R.; Ige, J.; Williams, B.; Pilkington, P.; Eaton, E.; Michalec, A. Healthy buildings for a healthy city: Is the public health evidence base informing current building policies? Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 719, 137146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, A.; Castillo-Salgado, C. Associations between Green Building Design Strategies and Community Health Resilience to Extreme Heat Events: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allen, J.G.; MacNaughton, P.; Laurent, J.G.; Flanigan, S.S.; Eitland, E.S.; Spengler, J.D. Green Buildings and Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2015, 2, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cedeno-Laurent, J.G.; Williams, A.; MacNaughton, P.; Cao, X.; Eitland, E.; Spengler, J.; Allen, J. Building Evidence for Health: Green Buildings, Current Science, and Future Challenges. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liddell, C.; Morris, C. Fuel poverty and human health: A review of recent evidence. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howieson, S.G.; Hogan, M. Multiple deprivation and excess winter deaths in Scotland. J. R. Soc. Promot. Health 2005, 125, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.; Carmichael, C.; Murray, V.; Dengel, A.; Swainson, M. Defining indoor heat thresholds for health in the UK. Perspect. Public Health 2013, 133, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verriele, M.; Schoemaecker, C.; Hanoune, B.; Leclerc, N.; Germain, S.; Gaudion, V.; Locoge, N. The MERMAID study: Indoor and outdoor average pollutant concentrations in 10 low-energy school buildings in France. Indoor Air 2016, 26, 702–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collignan, B.; Le Ponner, E.; Mandin, C. Relationships between indoor radon concentrations, thermal retrofit and dwelling characteristics. J. Environ. Radioact. 2016, 165, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, P.; Rees, D.; Daraktchieva, Z.; McColl, N.; Bradley, J.; Hamilton, I.; Davies, M. Home energy efficiency and radon: An observational study. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 854–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, W. Impact of constructional energy-saving measures on radon levels indoors. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressyanov, D.; Dimitrov, D.; Dimitrova, I. Energy-efficient reconstructions and indoor radon: The impact assessed by CDs/DVDs. J. Environ. Radioact. 2015, 143, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilyev, A.; Yarmoshenko, I. Effect of energy-efficient measures in building construction on indoor radon in Russia. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2017, 174, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmoshenko, I.V.; Vasilyev, A.V.; Onishchenko, A.D.; Kiselev, S.M.; Zhukovsky, M.V. Indoor radon problem in energy efficient multi-storey buildings. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2014, 160, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilyev, A.V.; Yarmoshenko, I.V.; Zhukovsky, M.V. Low air exchange rate causes high indoor radon concentration in energy-efficient buildings. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2015, 164, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghele, B.D.; Botoș, M.; Beldean-Galea, S.; Cucoș, A.; Catalina, T.; Dicu, T.; Dobrei, G.; Florică, Ș.; Istrate, A.; Lupulescu, A.; et al. Comprehensive survey on radon mitigation and indoor air quality in energy efficient buildings from Romania. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 751, 141858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigg, S.; Cautley, D.; Francisco, P.W. Impacts of weatherization on indoor air quality: A field study of 514 homes. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallner, P.; Munoz, U.; Tappler, P.; Wanka, A.; Kundi, M.; Shelton, J.F.; Hutter, H.P. Indoor Environmental Quality in Mechanically Ventilated, Energy-Efficient Buildings vs. Conventional Buildings. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14132–14147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Leivo, V.; Prasauskas, T.; Taubel, M.; Martuzevicius, D.; Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U. Effects of energy retrofits on Indoor Air Quality in multifamily buildings. Indoor Air 2019, 29, 686–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, T.; Hering, M.; Burkner, K.; Hirsch, D.; Leupold, W.; Kerkmann, M.L.; Kuhlisch, E.; Jatzwauk, L. House-dust-mite allergen concentrations (Der f 1) and mold spores in apartment bedrooms before and after installation of insulated windows and central heating systems. Allergy 2000, 55, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R.A.; Thornton, C.R.; Nikolaou, V.; Osborne, N.J. Fuel poverty increases risk of mould contamination, regardless of adult risk perception & ventilation in social housing properties. Environ. Int. 2015, 79, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sharpe, R.A.; Cocq, K.L.; Nikolaou, V.; Osborne, N.J.; Thornton, C.R. Identifying risk factors for exposure to culturable allergenic moulds in energy efficient homes by using highly specific monoclonal antibodies. Environ. Res. 2016, 144, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spertini, F.; Berney, M.; Foradini, F.; Roulet, C.A. Major mite allergen Der f 1 concentration is reduced in buildings with improved energy performance. Allergy 2010, 65, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculita-Hirzel, H.; Yang, S.; Hager Jörin, C.; Perret, V.; Licina, D.; Goyette Pernot, J. Fungal Contaminants in Energy Efficient Dwellings: Impact of Ventilation Type and Level of Urbanization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, K.; Taft, D.; Ward, D.V.; Green, B.J.; Chew, G.L.; Shamsaei, B.; Meller, J.; Indugula, R.; Reponen, T. Variability of indoor fungal microbiome of green and non-green low-income homes in Cincinnati, Ohio. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610–611, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbez, M.; Wyart, G.; Le Ponner, E.; Ramalho, O.; Ribéron, J.; Mandin, C. Indoor air quality in energy-efficient dwellings: Levels and sources of pollutants. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 318–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leivo, V.; Prasauskas, T.; Du, L.; Turunen, M.; Kiviste, M.; Aaltonen, A.; Martuzevicius, D.; Haverinen-Shaughnessy, U. Indoor thermal environment, air exchange rates, and carbon dioxide concentrations before and after energy retro fits in Finnish and Lithuanian multi-family buildings. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 621, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, K.C.; Chew, G.L.; Schaffer, C.; Ryan, P.H.; Brokamp, C.; Grinshpun, S.A.; Adamkiewicz, G.; Chillrud, S.; Hedman, C.; Colton, M.; et al. Indoor air quality in green-renovated vs. non-green low-income homes of children living in a temperate region of US (Ohio). Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 554–555, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, S.; Perret, V.; Hager Jörin, C.; Niculita-Hirzel, H.; Goyette Pernot, J.; Licina, D. Volatile organic compounds in 169 energy-efficient dwellings in Switzerland. Indoor Air 2020, 30, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baumgartner, J.; Clark, S.; Carter, E.; Lai, A.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, M.; Schauer, J.J.; Yang, X. Effectiveness of a Household Energy Package in Improving Indoor Air Quality and Reducing Personal Exposures in Rural China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 9306–9316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Syal, M.; Grady, S.C.; Korkmaz, S. Effects of green buildings on employee health and productivity. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 1665–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gawande, S.; Tiwari, R.R.; Narayanan, P.; Bhadri, A. Indoor Air Quality and Sick Building Syndrome: Are Green Buildings Better than Conventional Buildings? Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 24, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargocki, P.; Wyon, D.P.; Sundell, J.; Clausen, G.; Fanger, P.O. The effects of outdoor air supply rate in an office on perceived air quality, sick building syndrome (SBS) symptoms and productivity. Indoor Air 2000, 10, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedge, A.; Dorsey, J.A. Green buildings need good ergonomics. Ergonomics 2013, 56, 492–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedge, A.; Miller, L.; Dorsey, J.A. Occupant comfort and health in green and conventional university buildings. Work 2014, 49, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, J.V.; Norback, D.; Wieslander, G.; Hollund, B.E.; Florvaag, E.; Haugen, E.N.; Moen, B.E. Symptoms, complaints, ocular and nasal physiological signs in university staff in relation to indoor environment—temperature and gender interactions. Indoor Air 2008, 18, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garland, E.; Steenburgh, E.T.; Sanchez, S.H.; Geevarughese, A.; Bluestone, L.; Rothenberg, L.; Rialdi, A.; Foley, M. Impact of LEED-certified affordable housing on asthma in the South Bronx. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Act. 2013, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breysse, J.; Jacobs, D.E.; Weber, W.; Dixon, S.; Kawecki, C.; Aceti, S.; Lopez, J. Health outcomes and green renovation of affordable housing. Public Health Rep. 2011, 126 (Suppl. 1), 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breysse, J.; Dixon, S.L.; Jacobs, D.E.; Lopez, J.; Weber, W. Self-reported health outcomes associated with green-renovated public housing among primarily elderly residents. J. Public Health Manag. Pract. 2015, 21, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rudge, J.; Gilchrist, R. Excess winter morbidity among older people at risk of cold homes: A population-based study in a London borough. J. Public Health 2005, 27, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Webb, E.; Blane, D.; de Vries, R. Housing and respiratory health at older ages. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2013, 67, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, R.A.; Thornton, C.R.; Nikolaou, V.; Osborne, N.J. Higher energy efficient homes are associated with increased risk of doctor diagnosed asthma in a UK subpopulation. Environ. Int. 2015, 75, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, W.; Jones, N.; Lannon, S.; Jenkins, H. Social and health outcomes following upgrades to a national housing standard: A multilevel analysis of a five-wave repeated cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlton, E.J.; Barton, K.; Shrestha, P.M.; Humphrey, J.; Newman, L.S.; Adgate, J.L.; Root, E.; Miller, S. Relationships between home ventilation rates and respiratory health in the Colorado Home Energy Efficiency and Respiratory Health (CHEER) study. Environ. Res. 2019, 169, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Crane, J.; Chapman, R.; Fougere, G. Improving health and energy efficiency through community-based housing interventions. Int. J. Public Health 2011, 56, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howden-Chapman, P.; Matheson, A.; Crane, J.; Viggers, H.; Cunningham, M.; Blakely, T.; Cunningham, C.; Woodward, A.; Saville-Smith, K.; O’Dea, D.; et al. Effect of insulating existing houses on health inequality: Cluster randomised study in the community. BMJ 2007, 334, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomson, H.; Snell, C.; Bouzarovski, S. Health, Well-Being and Energy Poverty in Europe: A Comparative Study of 32 European Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahrentzen, S.; Erickson, J.; Fonseca, E. Thermal and health outcomes of energy efficiency retrofits of homes of older adults. Indoor Air 2016, 26, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shortt, N.; Rugkåsa, J. “The walls were so damp and cold” fuel poverty and ill health in Northern Ireland: Results from a housing intervention. Health Place 2007, 13, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, R.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Viggers, H.; O’Dea, D.; Kennedy, M. Retrofitting houses with insulation: A cost-benefit analysis of a randomised community trial. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, C.N.; Jiang, S.; Nascimento, C.; Rodgers, S.E.; Johnson, R.; Lyons, R.A.; Poortinga, W. The short-term health and psychosocial impacts of domestic energy efficiency investments in low-income areas: A controlled before and after study. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Poortinga, W.; Rodgers, S.E.; Lyons, R.A.; Anderson, P.; Tweed, C.; Grey, C.; Jiang, S.; Johnson, R.; Watkins, A.; Winfield, T.G. Public Health Research. In The Health Impacts of Energy Performance Investments in Low-Income Areas: A Mixed-Methods Approach; Public Health Research; NIHR Journals Library: Southampton, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, A.; Jones, T.; Sherratt, S.; Sharpe, R.A. Use of Simple Telemetry to Reduce the Health Impacts of Fuel Poverty and Living in Cold Homes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Angelini, V.; Daly, M.; Moro, M.; Navarro Paniagua, M.; Sidman, E.; Walker, I.; Weldon, M. Public Health Research. In The Effect of the Winter Fuel Payment on Household Temperature and Health: A Regression Discontinuity Design Study; Public Health Research; NIHR Journals Library: Southampton, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sartini, C.; Tammes, P.; Hay, A.D.; Preston, I.; Lasserson, D.; Whincup, P.H.; Wannamethee, S.G.; Morris, R.W. Can we identify older people most vulnerable to living in cold homes during winter? Ann. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 1–7.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peralta, A.; Camprubi, L.; Rodriguez-Sanz, M.; Basagana, X.; Borrell, C.; Mari-Dell’Olmo, M. Impact of energy efficiency interventions in public housing buildings on cold-related mortality: A case-crossover analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1192–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Umishio, W.; Ikaga, T.; Kario, K.; Fujino, Y.; Hoshi, T.; Ando, S.; Suzuki, M.; Yoshimura, T.; Yoshino, H.; Murakami, S. Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Relationship Between Home Blood Pressure and Indoor Temperature in Winter: A Nationwide Smart Wellness Housing Survey in Japan. Hypertension 2019, 74, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bueno, J.A.; Linares, C.; Sánchez-Guevara, C.; Martinez, G.S.; Mirón, I.J.; Núñez-Peiró, M.; Valero, I.; Díaz, J. The effect of cold waves on daily mortality in districts in Madrid considering sociodemographic variables. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]