Perceptions of Fertility Physicians Treating Women Undergoing IVF Using an Egg Donation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Data Analysis

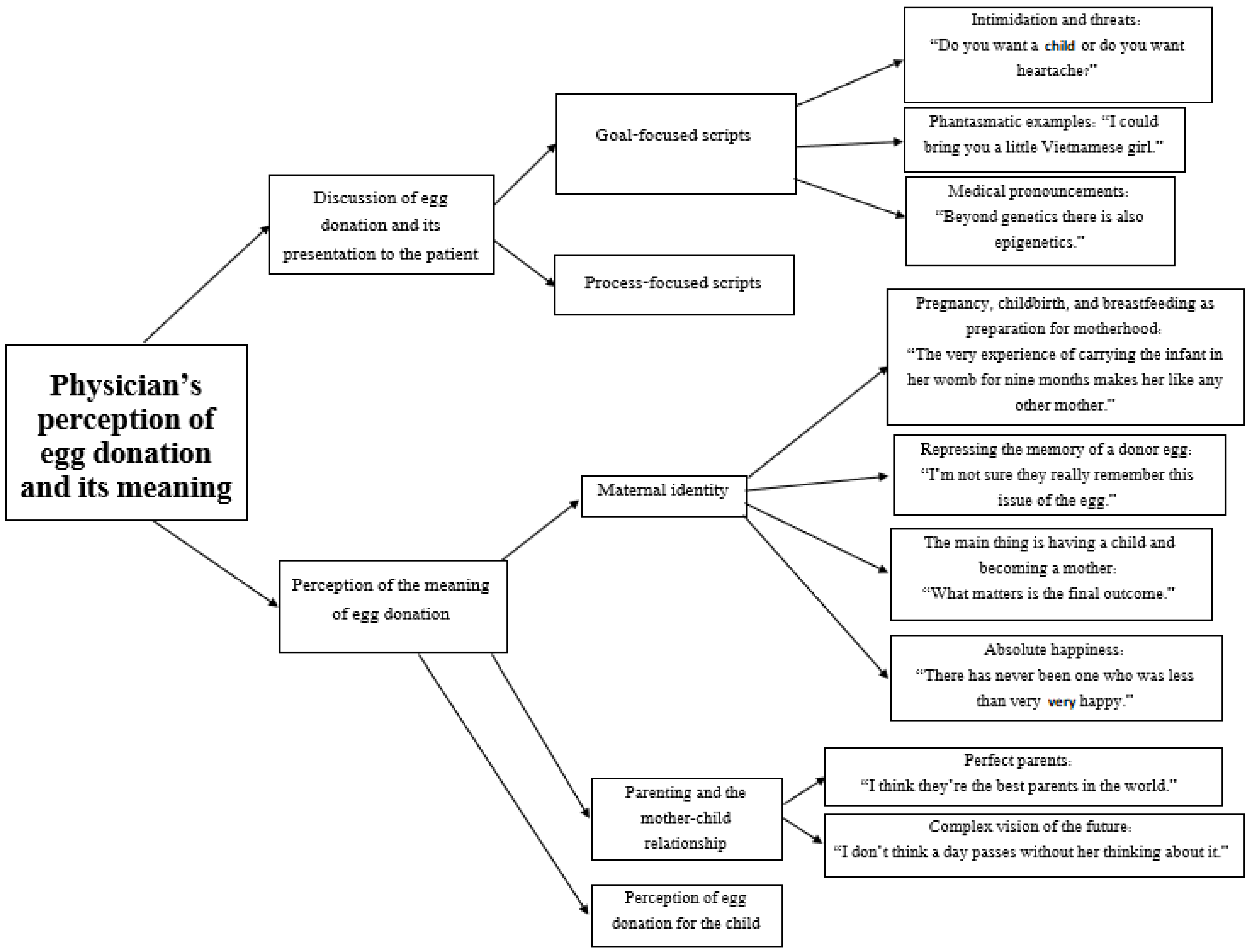

3. Results

3.1. Theme 1: Discussing the Use of Egg Donation and Its Presentation to the Patient

“I may have developed a format that I think sells the idea well...I don’t know if it sells it well, but at least I’m trying to”.(Interviewee 14)

3.1.1. Goal-Focused Scripts: “Do You Want a Child or Do You Want Treatments?”

3.1.2. Intimidation and Threats: “Do You Want a Child or Do You Want Heartache?”

“I always ask them What do you want? Do you want a child or do you want heartache? Tell me what you want. Do you want to stew in your own juice, and see failure after failure after failure, or do you finally want a child? Do you want to go to a park where they ask ‘Are you the mother or the grandmother?’”(Interviewee 6)

“There are women I tell very quickly, ‘Listen, this is a waste of time, accept an egg donation’. … When I see that it’s hopeless and a waste of time and a waste of the hormones they get (which we’re not sure are so healthy), I tell them, ‘Listen, do you want to be a mother before the age of about 200 or 50? It’s time to use egg donation. This is a waste of time’”.(Interviewee 13)

“I tell her to look on the other side of the mountain for what she wants...whether in a year she wants to walk around IVF units doing blood tests, or she wants to walk down the street with a baby carriage. I always tell the woman, ‘OK, it’s clear, everyone wants to be healthy and rich, but your options now are either to give up on being a parent, to adopt, or to accept an egg donation, conceive, and give birth. So...which is the lesser evil? The lesser evil is egg donation’…And I tell her, ‘Listen, if that’s what you want…if your life’s dream is to be a mother, then you have to fulfill your life’s dream, like...what does it matter?...The means are less important. I don’t know…if your life’s dream is to propagate your genes, it probably won’t happen. However, if your dream is to be a mother and get pregnant, to give birth...’”(Interviewee 10)

3.1.3. Phantasmatic Examples: “I Could Bring You a Little Vietnamese Girl”

“Sometimes I say this to women who do not agree to egg donation, I tell them, ‘Imagine for a moment, that there’s a knock on the door and you find a basket with a baby inside and a note that says, ‘I can never raise this baby. If you want it, it’s yours’. And you bring this baby into your home, a newborn baby, and.. I’m asking you now, how long will it take you to love the child as if you gave birth to it?’ She says, ‘Probably two or three days’”.(Interviewee 1)

“When they come to me, they say, ‘I’ll never be able to.’ I tell them, ‘Listen, I could bring you a little two-week-old Vietnamese girl, in a year we would meet and you’d love her more than anything else in the world’”.(Interviewee 16)

3.1.4. Medical Pronouncements: “Beyond Genetics There Is Also Epigenetics”

“I present it as a matter of no choice. I usually give it a title, ‘What you want is a child. To get it, you need semen, you need eggs, and you need a uterus, and... hopefully, it really works like that... I‘m very happy that [in your case] the sperm is normal and the uterus is fine. Now if we get an egg you can experience pregnancy, birth, and motherhood’”.(Interviewee 14)

“[I tell them] that there are other options. I simply raise the possibility. And I tell them about studies that have shown an excellent bond...I beautify the story a little and say that beyond genetics there is also epigenetics, and that this child will later love the same things that the mother loves, and he will sleep with his hand on his forehead like her...all kinds of things…everything they need to hear. And it’s also true. It’s not that I’m lying. I’m trying to show them both the positive sides...of being a younger mother instead of waiting until the age of 45 for a donation”.(Interview No. 11)

3.1.5. Process-Focused Scripts: “There Is a Slow Process of Digesting the Information Internally”

“I also tell everyone that it’s…I warn them that it’s hard to digest, that they need to go home, and when she’s convinced...by me or by another doctor, they will come to internalize it. But it’s a process. I don’t remember anyone who, at the end, wasn’t open to it. There’s a time of internal processing, of slowly getting used to it and digesting it, but eventually everyone accepts it... Usually, I think at some point I try to be more decisive and less vague. Also, I usually say, ‘Go home, sleep on it, read about it...even reading about it on the internet is okay...anywhere. Internalize it, ask questions if you have any, but...there’s no point in continuing like this’”.(Interviewee 14)

“I always advise them. I tell them all the options, including egg donation, so as not to miss the pregnancy train either... At first, almost no couple agrees. Almost. It takes a few treatments until they understand that this is what needs to be done... So I suggest, but I don’t press. I mean if she wants another treatment and another treatment. But then I try to set a goal with her. ‘So let’s decide. Let’s decide that you undergo another treatment or two and if that doesn’t work, we move on?’ Then it is easier for her…I always tell her, ‘You have to get to the point where you feel there was nothing you didn’t try in your desire to have a child. When we get to that point, it will be ok. However, we should try and set a clear timeline for that’”.(Interviewee 8)

“I do it gradually...I tell her, ‘You know there are all kinds of options, you know that if you lived in the US, you could not do 10 IVF treatments. They would probably suggest egg donation after two or three alternative treatments’... I never come right out and say...‘Listen to me’....That’s an awful kick in the stomach… it... also, how can you continue after that, it’s an expression of total lack of faith in the woman, so you too... from that moment on, you become a person they don’t believe in at all anymore. How can you continue to give her those treatments if you’ve declared that... So I say there are all kinds of options, some do surrogacy, and some do this... it’s one of the options... In most cases I’ll tell her, look you can do follow-ups and this and that... I also see her response, because, look, most come prepared… If I see that she’s not ready, I tell her, let’s do a month or two of follow-ups on your health, come as if… And then with her own eyes she sees she doesn’t have the follicles. It makes it much easier... Like if you do a PGS for a woman, check her embryos and she sees that each one is chromosomally abnormal, it makes it very easy for her, she says ok, let’s move on to the egg donation”.(Interviewee 16)

3.2. Theme 2: The Doctor’s Perception of the Meaning of Egg Donation

3.2.1. Maternal Identity

3.2.2. Pregnancy, Childbirth and Breastfeeding as Preparation for Motherhood: “The Very Experience of Carrying the Infant in Her Womb for Nine Months Makes Her Like Any Other Mother”

“The very experience of carrying the infant in her womb for nine months makes her like any other mother. It’s probably different from adoption when suddenly a new child lands in the home. No, here there are expectations, and there’s a date and she feels the baby moving, and ultrasounds, and good and not good... I think in terms of preparation it’s just like any other mother. It doesn’t seem different to me”.(Interviewee 1)

“It’s something very abstract, this part. I mean that this is an egg from someone else. I still think that the bonding element, in my opinion, is the 9 months in the womb, and the mutual experiences of birth, and breastfeeding, and the first year after the birth. It seems to me that this is the important part. And it’s something abstract. Think of yourself. Somebody tells you you’re actually your father’s and your mother’s child and you’ve been with her for nine months but the egg is someone else’s. Like, so what? You are you. and you won’t suddenly love your mother less”.(Interviewee 14)

3.2.3. Repressing the Memory of a Donor Egg: “I’m Not Sure They Really Remember This Issue of the Egg”

“Once the pregnancy begins, they forget…I’ve been in the field for 20 years, and I don’t remember anyone who came and said ‘I regret that I accepted an egg donation.’ I don’t remember a single one like that”.(Interviewee 5)

“I always think to myself, I’m not sure they really remember this issue of the egg. I think once they have a baby to raise, it’s not so important. It’s not there anymore. Life keeps carrying them forward and they have so much to do with this child...to bring it up and educate it”.(Interviewee 6)

“I don’t have the tools of a psychologist, but when you see a heartbeat on the ultrasound, you’re already at a point when it would be very interesting to see if there’s any difference between a pregnancy from a donor egg and one that isn’t. In my opinion, there’s no difference. From that moment, it all comes together and a pregnancy begins, a full pregnancy, regardless of how it began. Perhaps, subconsciously they tend to think, ‘Maybe it was from my egg after all and it’s impossible to know.’ I don’t know. And it doesn’t matter how the child looks afterward, who it looks like, if anyone. It always resembles someone in the family when they were young. ‘That’s exactly what I looked like’”.(Interviewee 14)

“A woman who accepts a donor egg, as soon as she makes the switch in her head and moves on, she’s the happiest mother in the world. They have a child, they’re happy, they’ve already forgotten where the egg came from. They want a child, a healthy child”.(Interviewee 17)

3.2.4. The Main Thing Is Having a Child and Becoming a Mother: “What Matters Is the Final Outcome”

“I think what matters is the final outcome and if the final outcome is good and it ultimately fulfills the dream of parenting and raising children, then even if it happened late and even if it took a little longer than expected and even if it wasn’t in the usual way, I think that’s what matters”.(Interviewee 5)

“Whoever arrives at egg donation, arrives at peace of mind. That’s how I see it. It’s a kind of safe haven. Because this whole war, what is it for? A child. For the child. It is all for the child. It is not about being pregnant. It is not about having a big belly, it’s for a child”.(Interviewee 6)

3.2.5. Absolute Happiness: “There Has Never Been One Who Was Less Than Very, Very Happy”

“My feeling is…if I have to quantify the happiness of the patients, I don’t see any difference in the happiness, say, of a patient who uses egg donation or sperm donation compared to the happiness of other patients. My impression is that their happiness…from the child is very similar. I see completeness and I see joy...and women who come and say ‘This is the best thing I’ve ever done in my life’”.(Interviewee 1)

“Now, I have a lot [of patients] who are single parents, I mean they need both an egg donation and a sperm donation… They’re happy!”(Interviewee 13)

“I tell you as someone who has accompanied hundreds of women, there has never been one who has been less than very, very happy.”(Interviewee 16)

“I have a lot of single women who have succeeding in having a child from their own eggs and a sperm donation. Then they come and say to me, ‘Listen, if I didn’t have a child with my egg and a sperm donation, then I would go through the process of sperm donation and egg donation. But now I have one child from my egg and a donor’s sperm, and on the other hand I’ll have a child from a donor egg and a donor’s sperm. Then nothing will be mine. And I’m afraid that I will love the child from the egg and sperm donation less than the child that came from my egg. That’s not right!’ But after that they turn around and they love the child with their whole heart... and they’re all the happiest women in the world”.(Interviewee 5)

3.3. Parenting and the Mother–Infant Bond

3.3.1. Perfect Parents: “I Think They’re the Best Parents in the World”

“It’s like they’re amazing parents...They love their children, really love them”.(Interviewee 3)

“I think they’re the best parents in the world. The children come from deep desire, expectation, choice. It’s not like my mother and father were about to get a divorce and suddenly they got pregnant... and my mother wasn’t even sure he was my father. Then they debated whether to get rid of me or keep me… and they said, fine, come on, we’ll keep you and I was born and they immediately divorced and you should know we didn’t want you and even thought about getting rid of you, but in the end, we kept you, you were born. In contrast, your mother wanted the most wonderful child in the world, and she didn’t have a partner, so she went to the sperm bank, and chose the best sperm, and she came and did inseminations here. It wasn’t some...one-night stand. Then she needed an egg from the Medical Center in Herzliya or from the Ukraine, and put them together. She had to work for it!”(Interviewee 5)

3.3.2. Complex Vision of the Future: “I Don’t Think a Day Passes without Her Thinking about It”

“Afterwards, parenting…I think it’s…you know, it will always stay with her. I don’t think it makes her a better or worse mother.... I don’t think a day passes without her thinking about it. That’s my opinion. But on the other hand, there are 24 h in a day, and for 23.5 of them, you’re happy because you have a family and more than one child, so I think we did something. We did something”.(Interviewee 9)

“Ask couples who have adopted and have a biological child, they won’t understand what you’re talking about. Ask her how she feels....I’m not going to tell you that there were no people who said,...Look…you know there is always a feeling of having missed the chance, people usually waited and waited....Look…as soon as you go to the doctor at the age of 45 for treatments it brings your whole life up, all the guys who wanted to marry you, or that you imagined wanted to marry you, or your mom imagined it. I mean, it brings it all up, the 30 years of failure. So it’s obvious that with an egg donation as well, it could be that in another 10 years, she’ll sit in the park and say, ‘I wonder if I’d married at the age of 20, what my grandchildren running around here now would look like, something like that’”.(Interviewee 16)

3.3.3. Perceptions of Egg Donation from the Point of View of the Child

“I wouldn’t want my mother to come to me one day and tell me, just to let you know, you’re not my biological child, because I don’t know what that means… What I could understand from her telling me that is that she doesn’t really love me… It would be better not to tell me such things. Even when people tell me bad things, I say keep it to yourself, what do I need your problems for... For a child it’s pretty bad... Like children get anxious. If she’s not my biological mother, and I just quarreled with her about the scooter, will she throw me out of the house?”(Interviewee 16)

“Let’s say that with life and maturity and defense and repression mechanisms and everything else they are...yes, they’ll learn how to live with...it and make it... For them it will fade. It will become less significant. But the child won’t have…they won’t be able to process it. I think it’s awfully hard for a child! I really feel sorry for these children”.(Interviewee 4)

“Biologically, there’s a small problem with it. If genetic problems develop later, and they find out they’re not the child of their mother, okay? It raises some doubts in the corner of your mind. But if this isn’t the case, I don’t think it’s good for them....It’s like if someone tells you today that you are not your mother’s daughter, what would that do to you? Upheaval. It would shake you to the core, and why do that to you? So, if there’s a genetic reason, then maybe it’s worth [telling you]. Again, this is a question that has to be dealt with”.(Interviewee 6)

“With egg donation I know the chance is better, so I feel good about it. On the other hand, with egg donation there is always the... From my point of view it’s problematic. Because if I perform an egg donation for someone who has no eggs at 40, it’s much easier for me, because I feel it’s legitimate. When I perform an egg donation at an older age...there’s an ethical problem with it. The age. The mother is old. That means the child will grow up in a home with elderly parents… The moment I do this knowingly, in this way, it’s a little hard sometimes. You make a dream come true for them, but you forget that you’re putting someone in the equation who is…who will be born into a difficult reality”.(Interviewee 12)

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications of the Study

4.3. Suggestions for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weilenmann, S.; Schnyder, U.; Parkinson, B.; Corda, C.; von Känel, R.; Pfaltz, M.C. Emotion Transfer, Emotion Regulation, and Empathy-Related Processes in Physician-Patient Interactions and Their Association with Physician Well-Being: A Theoretical Model. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu-Sharkia, S.; Taubman–Ben-Ari, O.; Mofareh, A. Secondary traumatization and personal growth of healthcare teams in maternity and neonatal wards: The role of differentiation of self and social support. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020, 22, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cedar, S.H.; Walker, G. Protecting the wellbeing of nurses providing end-of-life care. Nurs. Times 2020, 116, 36–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kerasidou, A.; Horn, R. Making space for empathy: Supporting doctors in the emotional labour of clinical care. BMC Med. Ethic. 2016, 17, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGinley, E.; O’Reilly, J. Psychodynamic supervision for junior hospital doctors. Psychiatr. Bull. 1994, 18, 85–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, R.; Shoji, K.; Douglas, A.; Melville, E.; Luszczynska, A.; Benight, C.C. A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, I.; Nettleton, S.; Burrows, R. The views of doctors on their working lives: A qualitative study. J. R. Soc. Med. 2008, 101, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granek, L.; Barbera, L.; Nakash, O.; Cohen, M.; Krzyzanowska, M. Experiences of Canadian Oncologists with Difficult Patient Deaths and Coping Strategies Used. Curr. Oncol. 2017, 24, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.; Adjei, A.; Meyskens, F.L. When Your Favorite Patient Relapses: Physician Grief and Well-Being in the Practice of Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 2616–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boivin, J.; Domar, A.D.; Shapiro, D.B.; Wischmann, T.; Fauser, B.C.J.M.; Verhaak, C. Tackling burden in ART: An integrated approach for medical staff. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 941–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchin, F.; Leone, D.; Tamanza, G.; Costa, M.; Sulpizio, P.; Canzi, E.; Vegni, E. Working with Infertile Couples Seeking Assisted Reproduction: An Interpretative Phenomenological Study With Infertility Care Providers. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalos, A. Breaking bad news concerning fertility. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghi, L.; Menichetti, J.; Vegni, E. Editorial: Patient-Centered Infertility Care: Current Research and Future Perspectives on Psychosocial, Relational, and Communication Aspects. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 712485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaitchik, S.; Kreitler, S.; Shared, S.; Schwartz, I.; Rosin, R. Doctor-patient communication in a cancer ward. J. Cancer Educ. 1992, 7, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite, R.C.; Makuch, M.Y.; Petta, C.A.; Morais, S.S. Women’s satisfaction with physicians’ communication skills during an infertility consultation. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 59, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grill, E. Role of the mental health professional in education and support of the medical staff. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, D.; Menichetti, J.; Barusi, L.; Chelo, E.; Costa, M.; De Lauretis, L.; Ferraretti, A.P.; Livi, C.; Luehwink, A.; Tomasi, G.; et al. Breaking bad news in assisted reproductive technology: A proposal for guidelines. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramond, J. Counselling needs of patients receiving treatment with gamete donation. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 8, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. Identity development during the transition to motherhood: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 1999, 17, 281–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsiti, W. The Effect of Maternal Role Intervention with Increased Maternal Role Identity Attainment in Pregnancy and Infant Growth: A Meta-analysis. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 8, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akker, O.V.D. A review of family donor constructs: Current research and future directions. Hum. Reprod. Update 2005, 12, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golombok, S.; Lycett, E.; MacCallum, F.; Jadva, V.; Murray, C.; Rust, J.; Abdalla, H.; Jenkins, J.; Margara, R. Parenting Infants Conceived by Gamete Donation. J. Fam. Psychol. 2004, 18, 443–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imrie, S.; Jadva, V.; Fishel, S.; Golombok, S. Families Created by Egg Donation: Parent-Child Relationship Quality in Infancy. Child Dev. 2018, 90, 1333–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applegarth, L.D.; Riddle, M.R. What do we know and what can we learn from families created through egg donation? J. Infant Child Adolesc. Psychother. 2007, 6, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, S.; Golombok, S. Long-term outcomes of children conceived through egg donation and their parents: A review of the literature. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.; Golombok, S. To tell or not to tell: The decision-making process of egg-donation parents. Hum. Fertil. 2003, 6, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennings, G. Disclosure of donor conception, age of disclosure and the well-being of donor offspring. Hum. Reprod. 2017, 32, 969–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, J.K.; Voigt, P.; Schiffman, M.R.; Lee, S.; Besser, A.G.; Fino, M.E. Experiences and psychological outcomes of the oocyte donor: A survey of donors post-donation from one center. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2019, 36, 1999–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaldar, D. Egg donors’ motivations, experiences, and opinions: A survey of egg donors in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, D.; Borghi, L.; Del Negro, S.; Becattini, C.; Chelo, E.; Costa, M.; De Lauretis, L.; Ferraretti, A.P.; Giuffrida, G.; Livi, C.; et al. Doctor–couple communication during assisted reproductive technology visits. Hum. Reprod. 2018, 33, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, K. Is blood really thicker than water? Assisted reproduction and its impact on our thinking about family. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005, 26, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S. The qualitative research interview: A phenomenological and a hermeneutical mode of understanding. J. Phenomenol. Psychol. 1983, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, I. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Shkedi, A. Words That Try to Touch—Qualitative Research, Theory and Application; Ramot: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan, C. The Harmonics of relationship. In Meeting at the Crossroads, Women’s Psychology and Girls Development, Lyn Mikel Brown and Carol Gilligan; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 18–41. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui, E.Y.L.; Cheng, J.O.Y. When failed motherhood threatens womanhood: Using donor-assisted conception (DAC) as the last resort. Asian Women 2018, 34, 33–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, R.; Weissenberg, R.; Madgar, I. A child of “hers”: Older single mothers and their children conceived through IVF with both egg and sperm donation. Fertil. Steril. 2008, 90, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrie, S.; Jadva, V.; Golombok, S. “Making the child mine”: Mothers’ thoughts and feelings about the mother–Infant relationship in egg donation families. J. Fam. Psychol. 2020, 34, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart-Smith, S.J.; Smith, J.; Scott, E.J. To know or not to know? Dilemmas for women receiving unknown oocyte donation. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 2067–2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar Hava, E.; Shinkman Ben Zeev, A. Fertility from a to a Baby: Everything You Need to Know about Fertility Problems and Their Treatment; Yedioth Ahronoth: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, H.C.; Chen, H.C.; Chen, H.J.; Lu, K.; Hung, S.Y. Doctors’ emotional intelligence and the patient–doctor relationship. Med. Educ. 2008, 42, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schildmann, J.; Tan, J.; Salloch, S.; Vollmann, J. “Well, I Think There Is Great Variation…”: A Qualitative Study of Oncologists’ Experiences and Views Regarding Medical Criteria and Other Factors Relevant to Treatment Decisions in Advanced Cancer. Oncologist 2013, 18, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teman, E. The Medicalization of “Nature” in the “Artificial Body”: Surrogate Motherhood in Israel. Med. Anthr. Q. 2003, 17, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauprich, O.; Berns, E.; Vollmann, J. Information provision and decision-making in assisted reproduction treatment: Results from a survey in Germany. Hum. Reprod. 2011, 26, 2382–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.H.Y.; Lau, H.P.B.; Tam, M.Y.J.; Ng, E. A longitudinal study investigating the role of decisional conflicts and regret and short-term psychological adjustment after IVF treatment failure. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 2772–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.H.Y.; Lau, B.H.P.; Tam, M.Y.J.; Ng, E.H.Y. Preferred problem solving and decision-making role in fertility treatment among women following an unsuccessful in vitro fertilization cycle. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Berkel, D.; Cándido, A.; Pijffers, W.H. Becoming a mother by non-anonymous egg donation: Secrecy and the relationship between egg recipient, egg donor and egg donation child. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2007, 28, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, L.; Casey, P.; Jadva, V.; Golombok, S. ‘I was quite amazed’: Donor conception and parent–child relationships from the child’s perspective. Child. Soc. 2014, 28, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golombok, S.; Murray, C.; Jadva, V.; Lycett, E.; MacCallum, F.; Rust, J. Non-genetic and non-gestational parenthood: Consequences for parent–child relationships and the psychological well-being of mothers, fathers and children at age 3. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 1918–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, C.; MacCallum, F.; Golombok, S. Egg donation parents and their children: Follow-up at age 12 years. Fertil. Steril. 2006, 85, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkman, M. Being a ‘real mum’: Motherhood through donated eggs and embryos. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2008, 31, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson-Koku, G.; Grime, P. Emotion regulation and burnout in doctors: A systematic review. Occup. Med. 2019, 69, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ben-Kimhy, R.; Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. Perceptions of Fertility Physicians Treating Women Undergoing IVF Using an Egg Donation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127159

Ben-Kimhy R, Taubman–Ben-Ari O. Perceptions of Fertility Physicians Treating Women Undergoing IVF Using an Egg Donation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):7159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127159

Chicago/Turabian StyleBen-Kimhy, Reut, and Orit Taubman–Ben-Ari. 2022. "Perceptions of Fertility Physicians Treating Women Undergoing IVF Using an Egg Donation" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 7159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127159

APA StyleBen-Kimhy, R., & Taubman–Ben-Ari, O. (2022). Perceptions of Fertility Physicians Treating Women Undergoing IVF Using an Egg Donation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127159