Bullying Victimization and Mental Health among Migrant Children in Urban China: A Moderated Mediation Model of School Belonging and Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. School Bullying Victimization and Mental Health

1.2. Mediating Role of School Belonging

1.3. Moderating Role of Individual Resilience

1.4. The Context of This Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

2.2.2. Independent Variable

2.2.3. Mediating Variable

2.2.4. Moderating Variable

2.2.5. Control Variables

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2. Main Effect of Bullying Victimization

3.3. Mediating Effect of School Belonging

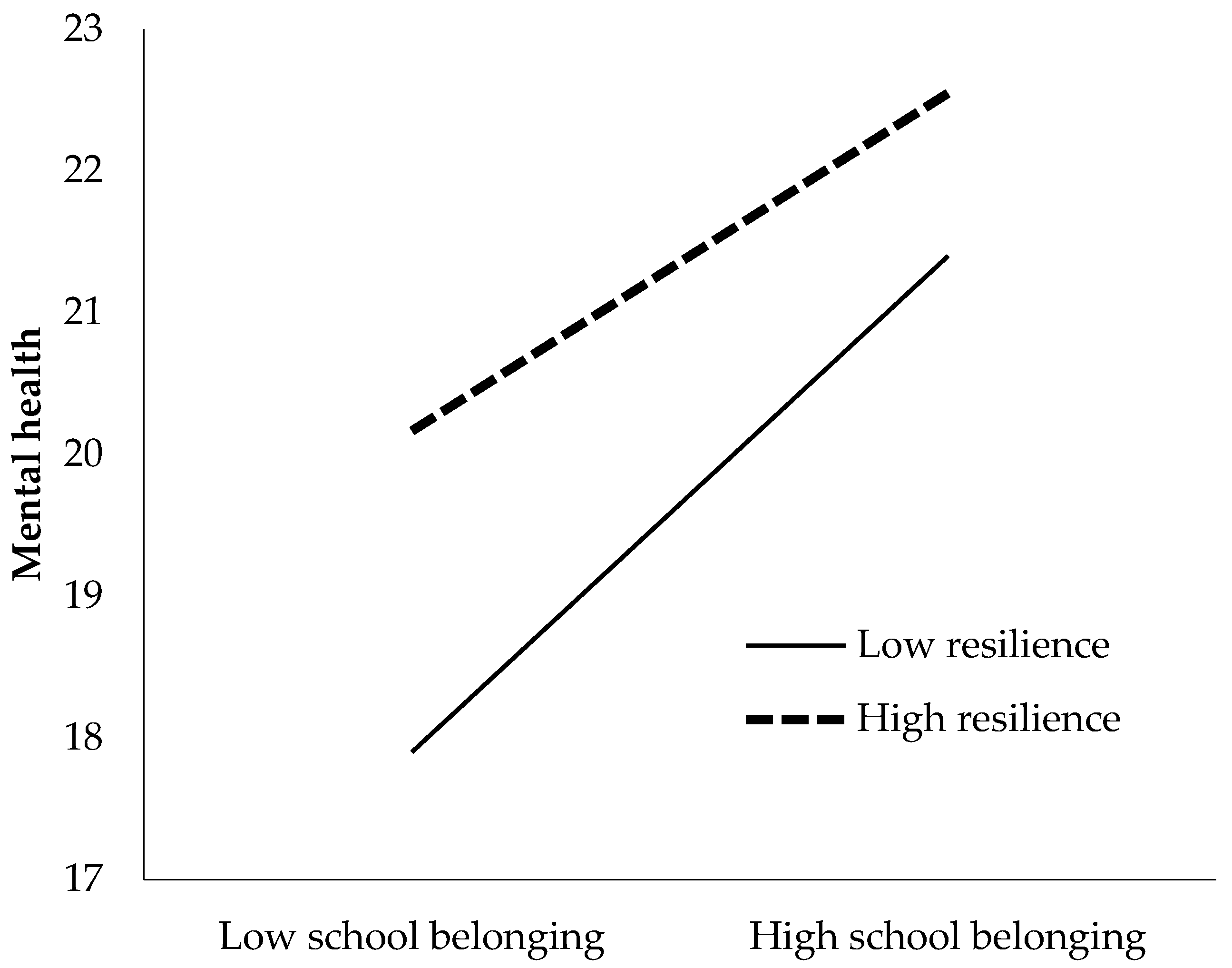

3.4. Moderating Effect of Resilience

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Olweus, D. Sweden. In The Nature of School Bullying: A Cross-National Perspective, 1st ed.; Smith, P.K., Morita, Y., Junger-Tas, J., Olweus, D., Catalano, R., Slee, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 10–11. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, S.; Wolke, D. Direct and Relational Bullying among Primary School Children and Academic Achievement. J. Sch. Psychol. 2004, 42, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). School Violence and Bullying: Global Status Report. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000246970?1 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483?2 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Pengpid, S.; Peltzer, K. Bullying Victimization and Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms among In-School Adolescents from Five ASEAN Countries. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 106, 104473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S.E.; Norman, R.E.; Suetani, S.; Thomas, H.J.; Sly, P.D.; Scott, J.G. Consequences of Bullying Victimization in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takizawa, R.; Maughan, B.; Arseneault, L. Adult Health Outcomes of Childhood Bullying Victimization: Evidence from a Five-Decade Longitudinal British Birth Cohort. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.C.O.; Wong, D.S.W. Traditional School Bullying and Cyberbullying in Chinese Societies: Prevalence and a Review of the Whole-School Intervention. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015, 23, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.; Xue, J.; Han, Z. School Bullying Victimization and Self-Rated Health and Life Satisfaction: The Gendered Buffering Effect of Educational Expectations. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 116, 105252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husky, M.M.; Delbasty, E.; Bitfoi, A.; Carta, M.G.; Goelitz, D.; Koç, C.; Lesinskiene, S.; Mihova, Z.; Otten, R.; Kovess-Masfety, V. Bullying Involvement and Self-Reported Mental Health in Elementary School Children across Europe. Child Abuse Negl. 2020, 107, 104601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, B.R.; Vaughn, M.G.; Salas-Wright, C.P.; Vaughn, S. Bullying Victimization Among School-Aged Immigrant Youth in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G.W.J.M.; Boer, M.; Titzmann, P.F.; Cosma, A.; Walsh, S.D. Immigration Status and Bullying Victimization: Associations across National and School Contexts. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2020, 66, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WEIBO. The Review of Education for Children of Migrant Population in China in 2020. Available online: https://weibo.com/ttarticle/p/show?id=2309404618960284025088 (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Song, Y. What Should Economists Know about the Current Chinese Hukou System? China Econ. Rev. 2014, 29, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.W. China: Internal Migration. In The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration; Ness, I., Bellwood, P.S., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 980–994. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W. Residential Segregation and Perceptions of Social Integration in Shanghai, China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1484–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Su, S.; Li, X.; Tam, C.C.; Lin, D. Perceived Discrimination, Schooling Arrangements and Psychological Adjustments of Rural-to-Urban Migrant Children in Beijing, China. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2014, 2, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Chen, L.; Harrison, S.E.; Guo, H.; Li, X.; Lin, D. Peer Victimization and Depressive Symptoms Among Rural-to-Urban Migrant Children in China: The Protective Role of Resilience. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, K.; To, S. Migrant Status, Social Support, and Bullying Perpetration of Children in Mainland China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 107, 104534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; To, S. School Climate, Bystanders’ Responses, and Bullying Perpetration in the Context of Rural-to-Urban Migration in China. Deviant Behav. 2021, 42, 1416–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, J. Study on the Prevalence and Associated Factors of Child Bullying Victimization among Migrant Children—Findings Based on A School for Children of Migrant Workers in Beijing. Soc. Constr. 2019, 6, 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, G.; Allen, K.-A.; Tanhan, A. School Bullying, Mental Health, and Wellbeing in Adolescents: Mediating Impact of Positive Psychological Orientations. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-K.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Niu, G.-F.; Sun, X.-J.; Fan, C.-Y. Bullying Victimization and Depression in Chinese Children: A Moderated Mediation Model of Resilience and Mindfulness. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 104, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, H.; Cai, L.; He, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, T.; Yang, R.; Xu, X.; Lu, J.; Xiao, Y. Resilience Mediates the Association between School Bullying Victimization and Self-Harm in Chinese Adolescents. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemesh, D.O.; Heiman, T. Resilience and Self-Concept as Mediating Factors in the Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Sense of Well-Being among Adolescents. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2021, 26, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arseneault, L. The Long-Term Impact of Bullying Victimization on Mental Health. World Psychiatry 2017, 16, 27–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arseneault, L.; Bowes, L.; Shakoor, S. Bullying Victimization in Youths and Mental Health Problems: ‘Much Ado about Nothing’? Psychol. Med. 2010, 40, 717–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reijntjes, A.; Kamphuis, J.H.; Prinzie, P.; Telch, M.J. Peer Victimization and Internalizing Problems in Children: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Child Abuse Negl. 2010, 34, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copeland, W.E.; Wolke, D.; Angold, A.; Costello, E.J. Adult Psychiatric Outcomes of Bullying and Being Bullied by Peers in Childhood and Adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2013, 70, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Q.; Xu, X.; Xiang, H.; Yang, Y.; Peng, P.; Xu, S. Bullying Victimization and Suicidal Ideation among Chinese Left-behind Children: Mediating Effect of Loneliness and Moderating Effect of Gender. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 111, 104848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.S.; Kral, M.J.; Sterzing, P.R. Pathways From Bullying Perpetration, Victimization, and Bully Victimization to Suicidality Among School-Aged Youth: A Review of the Potential Mediators and a Call for Further Investigation. Trauma Violence Abuse 2015, 16, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, X.-W.; Fan, C.-Y.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Zhou, Z.-K. Rumination Mediates and Moderates the Relationship between Bullying Victimization and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Early Adolescents. Child Indic. Res. 2019, 12, 1549–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strøm, I.F.; Aakvaag, H.F.; Birkeland, M.S.; Felix, E.; Thoresen, S. The Mediating Role of Shame in the Relationship between Childhood Bullying Victimization and Adult Psychosocial Adjustment. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2018, 9, 1418570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Hu, Y.; Sun, M.; Fei, J.; Li, C.; Liang, L.; Hu, Y. Association between Bullying Victimization and Symptoms of Depression among Adolescents: A Moderated Mediation Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanikola, M.N.K.; Lyberg, A.; Holm, A.-L.; Severinsson, E. The Association between Deliberate Self-Harm and School Bullying Victimization and the Mediating Effect of Depressive Symptoms and Self-Stigma: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4745791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duru, E.; Balkis, M. Exposure to School Violence at School and Mental Health of Victimized Adolescents: The Mediation Role of Social Support. Child Abuse Negl. 2018, 76, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Ran, H.; Fang, D.; Che, Y.; Donald, A.R.; Wang, S.; Peng, J.; Chen, L.; Lu, J. School Bullying Associated Suicidal Risk in Children and Adolescents from Yunnan, China: The Mediation of Social Support. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 300, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, L.M.; Demaray, M.K. Social Support as a Moderator Between Victimization and Internalizing–Externalizing Distress From Bullying. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 36, 383–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chi, P.; Long, H.; Ren, X. Bullying Victimization and Depression among Left-behind Children in Rural China: Roles of Self-Compassion and Hope. Child Abuse Negl. 2019, 96, 104072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, K.; Xie, H. Intrapersonal and Interpersonal Sources of Resilience: Mechanisms of the Relationship Between Bullying Victimization and Mental Health among Migrant Children in China. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2021, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. In Interpersonal Development, 1st ed.; Canter, D., Laursen, B., Žukauskienė, R., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 57–89. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenow, C.; Grady, K.E. The Relationship of School Belonging and Friends’ Values to Academic Motivation Among Urban Adolescent Students. J. Exp. Educ. 1993, 62, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, K.; Kern, M.L.; Vella-Brodrick, D.; Hattie, J.; Waters, L. What Schools Need to Know About Fostering School Belonging: A Meta-Analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 30, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggins, S.D.; Kuperminc, G.P.; Henrich, C.C.; Smalls-Glover, C.; Perilla, J.L. Aggression among Adolescent Victims of School Bullying: Protective Roles of Family and School Connectedness. Psychol. Violence 2016, 6, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.; Schneider, M.; Wornell, C.; Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J. Student’s Perceptions of School Safety: It Is Not Just About Being Bullied. J. Sch. Nurs. 2018, 34, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, M.K.; Espelage, D.L. A Cluster Analytic Investigation of Victimization Among High School Students. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2003, 19, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skues, J.L.; Cunningham, E.G.; Pokharel, T. The Influence of Bullying Behaviours on Sense of School Connectedness, Motivation and Self-Esteem. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 2005, 15, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Allen, K.-A.; Ryan, T. Exploring the Impacts of School Belonging on Youth Wellbeing and Mental Health among Turkish Adolescents. Child Indic. Res. 2020, 13, 1619–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. Understanding the Association between School Belonging and Emotional Health in Adolescents. Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 7, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, A.D.; Boyle, A.E.; Bakhtiari, F. Understanding Students’ Transition to High School: Demographic Variation and the Role of Supportive Relationships. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 2129–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shochet, I.M.; Dadds, M.R.; Ham, D.; Montague, R. School Connectedness Is an Underemphasized Parameter in Adolescent Mental Health: Results of a Community Prediction Study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2006, 35, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarf, D.; Moradi, S.; McGaw, K.; Hewitt, J.; Hayhurst, J.G.; Boyes, M.; Ruffman, T.; Hunter, J.A. Somewhere I Belong: Long-Term Increases in Adolescents’ Resilience Are Predicted by Perceived Belonging to the in-Group. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2016, 55, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begen, F.M.; Turner-Cobb, J.M. Benefits of Belonging: Experimental Manipulation of Social Inclusion to Enhance Psychological and Physiological Health Parameters. Psychol. Health 2015, 30, 568–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, S. Social Exclusion, Sense of School Belonging and Mental Health of Migrant Children in China: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 89, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaten, C.D.; Ferguson, J.K.; Allen, K.-A.; Brodrick, D.-V.; Waters, L. School Belonging: A Review of the History, Current Trends, and Future Directions. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2016, 33, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.P.; Merrin, G.J.; Ingram, K.M.; Espelage, D.L.; Valido, A.; El Sheikh, A.J. Examining Pathways between Bully Victimization, Depression, & School Belonging Among Early Adolescents. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2365–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brennan, L.M.; Furlong, M.J. Relations Between Students’ Perceptions of School Connectedness and Peer Victimization. J. Sch. Violence 2010, 9, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G. School Bullying and Youth Internalizing and Externalizing Behaviors: Do School Belonging and School Achievement Matter? Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G.; Allen, K.-A. School Victimization, School Belongingness, Psychological Well-Being, and Emotional Problems in Adolescents. Child Indic. Res. 2021, 14, 1501–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H.; Stewart, D.E.; Diaz-Granados, N.; Berger, E.L.; Jackson, B.; Yuen, T. What Is Resilience? Can. J. Psychiatry 2011, 56, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overbeek, G.; Zeevalkink, H.; Vermulst, A.; Scholte, R.H.J. Peer Victimization, Self-Esteem, and Ego Resilience Types in Adolescents: A Prospective Analysis of Person-Context Interactions. Soc. Dev. 2010, 19, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J. A Meta-Analysis of the Trait Resilience and Mental Health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 76, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianesini, G.; Brighi, A. Cyberbullying in the Era of Digital Relationships: The Unique Role of Resilience and Emotion Regulation on Adolescents’ Adjustment. In Technology and Youth: Growing Up in a Digital World, 1st ed.; Blair, S.L., Claster, P.N., Claster, S.M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2015; Volume 19, pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B.; Woodcock, S. Resilience, Bullying, and Mental Health: Factors Associated with Improved Outcomes. Psychol. Sch. 2017, 54, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinduja, S.; Patchin, J.W. Cultivating Youth Resilience to Prevent Bullying and Cyberbullying Victimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2017, 73, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, A.; Betts, L.R. Bullying Behaviors and Victimization Experiences Among Adolescent Students: The Role of Resilience. J. Genet. Psychol. 2014, 175, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Donnon, T. Understanding How Resiliency Development Influences Adolescent Bullying and Victimization. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 2010, 25, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes, L.; Maughan, B.; Caspi, A.; Moffitt, T.E.; Arseneault, L. Families Promote Emotional and Behavioural Resilience to Bullying: Evidence of an Environmental Effect. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2010, 51, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beightol, J.; Jevertson, J.; Gray, S.; Carter, S.; Gass, M. The Effect of an Experiential, Adventure-Based “Anti-Bullying Initiative” on Levels of Resilience: A Mixed Methods Study. J. Exp. Educ. 2009, 31, 420–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, G.; Hu, T. Bullying and Social Anxiety in Chinese Children: Moderating Roles of Trait Resilience and Psychological Suzhi. Child Abuse Negl. 2018, 76, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. PISA 2018 Results (Volume III): What School Life Means for Students’ Lives; PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L. Bullying Victimization, Self-Efficacy, Fear of Failure, and Adolescents’ Subjective Well-Being in China. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2021, 127, 106084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-H.; Gamble, J.H.; Lin, C.-Y. Peer Victimization’s Impact on Adolescent School Belonging, Truancy, and Life Satisfaction: A Cross-Cohort International Comparison. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a New Resilience Scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress. Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.-N.; Lau, J.T.F.; Mak, W.W.S.; Zhang, J.; Lui, W.W.S.; Zhang, J. Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale among Chinese Adolescents. Compr. Psychiatry 2011, 52, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, D.; Hong, J.S.; Kliem, S.; Bergmann, M.C. Consequences of Bullying on Adolescents’ Mental Health in Germany: Comparing Face-to-Face Bullying and Cyberbullying. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2019, 28, 2347–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, E.J.; Shochet, I.M.; Cockshaw, W.D.; Kelly, R.L. General Belonging Is a Key Predictor of Adolescent Depressive Symptoms and Partially Mediates School Belonging. Sch. Ment. Health 2020, 12, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Partial, Conditional, and Moderated Moderated Mediation: Quantification, Inference, and Interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2018, 85, 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G.; Reno, R.R. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions, 1st ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/improving-the-mental-and-brain-health-of-children-and-adolescents (accessed on 2 May 2022).

- Gini, G.; Marino, C.; Pozzoli, T.; Holt, M. Associations between Peer Victimization, Perceived Teacher Unfairness, and Adolescents’ Adjustment and Well-Being. J. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 67, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock, J.R. Bullying among Children. Child. Educ. 2002, 78, 130–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Arunkumar, R. Resiliency Research: Implications for Schools and Policy. Soc. Policy Rep. 1994, 8, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Stoddard, S.A.; Eisman, A.B.; Caldwell, C.H.; Aiyer, S.M.; Miller, A. Adolescent Resilience: Promotive Factors That Inform Prevention. Child. Dev. Perspect. 2013, 7, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergus, S.; Zimmerman, M.A. ADOLESCENT RESILIENCE: A Framework for Understanding Healthy Development in the Face of Risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2005, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, K.-A.; Jamshidi, N.; Berger, E.; Reupert, A.; Wurf, G.; May, F. Impact of School-Based Interventions for Building School Belonging in Adolescence: A Systematic Review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 34, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Oliver, T. Behavioral Activation for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Progress and Promise. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 28, 427–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, N.; Cross, D.; Monks, H.; Waters, S.; Falconer, S. Current Evidence of Best Practice in Whole-School Bullying Intervention and Its Potential to Inform Cyberbullying Interventions. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 2011, 21, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaustein, M.E.; Kinniburgh, K.M. Treating Traumatic Stress in Children and Adolescents: How to Foster Resilience through Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 147–194. [Google Scholar]

| N (%) | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| female | 473 (43.5) | ||

| male | 614 (56.5) | ||

| Hukou | |||

| urban | 240 (22.1) | ||

| rural | 847 (77.9) | ||

| Geographic location | |||

| Shanghai | 408 (37.5) | ||

| Nanjing | 679 (62.5) | ||

| Only child status | |||

| no | 887 (81.6) | ||

| yes | 200 (18.4) | ||

| School type | |||

| private | 854 (78.6) | ||

| public | 233 (21.4) | ||

| Number of school changes | |||

| 0 | 719 (66.1) | ||

| 1 | 210 (19.3) | ||

| 2 | 81 (7.5) | ||

| 3 | 64 (5.9) | ||

| 4 | 12 (1.1) | ||

| 5 | 1 (0.1) | ||

| Age | 12.3 (0.8) | 10–17 | |

| Family’s economic condition | 3.1 (0.6) | 1–5 | |

| Academic performance | 3.3 (1.2) | 1–5 | |

| Bullying victimization | 8.4 (3.7) | 6–24 | |

| School belonging | 19.8 (3.8) | 6–24 | |

| Resilience | 72.8 (17.0) | 0–100 | |

| Mental health | 20.3 (4.9) | 5–25 | |

| N | 1087 | 1087 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bullying victimization | 1 | |||

| 2. School belonging | −0.461 ** | 1 | ||

| 3. Resilience | −0.223 ** | 0.530 ** | 1 | |

| 4. Mental health | −0.421 ** | 0.534 ** | 0.417 ** | 1 |

| Model 1 Mental Health | Model 2 Mental Health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | β | b | S.E. | β | |

| Male | 0.401 | 0.290 | 0.041 | 0.674 * | 0.268 | 0.069 |

| Age | −0.073 | 0.199 | −0.011 | −0.128 | 0.183 | −0.020 |

| Rural hukou | 0.098 | 0.348 | 0.008 | 0.138 | 0.320 | 0.012 |

| Only child status | 0.345 | 0.373 | 0.027 | 0.261 | 0.343 | 0.021 |

| Nanjing | 1.912 *** | 0.341 | 0.190 | 1.194 *** | 0.318 | 0.119 |

| Number of school changes | −0.112 | 0.158 | −0.022 | −0.025 | 0.146 | −0.005 |

| Public school | −2.024 *** | 0.394 | −0.170 | −1.780 *** | 0.363 | −0.149 |

| Family’s economic condition | 1.045 *** | 0.251 | 0.125 | 0.915 *** | 0.231 | 0.109 |

| Academic performance | 0.658 *** | 0.127 | 0.155 | 0.445 *** | 0.118 | 0.105 |

| Bullying victimization | −0.509 *** | 0.036 | −0.386 | |||

| Intercept | 14.780 | 2.677 | 21.014 *** | 2.470 | ||

| R2 | 0.089 | 0.230 | ||||

| F | 11.743 *** | 32.145 *** | ||||

| Model 3 School Belonging | Model 4 Mental Health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | β | b | S.E. | β | |

| Male | 0.252 | 0.196 | 0.033 | 0.545 * | 0.248 | 0.055 |

| Age | −0.146 | 0.1343 | −0.029 | −0.052 | 0.170 | −0.008 |

| Rural hukou | −0.297 | 0.234 | −0.033 | 0.291 | 0.297 | 0.025 |

| Only child status | 0.056 | 0.252 | 0.006 | 0.232 | 0.318 | 0.018 |

| Nanjing | 0.693 ** | 0.233 | 0.089 | 0.837 ** | 0.296 | 0.083 |

| Number of schol changes | −0.159 | 0.107 | −0.040 | 0.057 | 0.135 | 0.011 |

| Public school | −0.930 *** | 0.266 | −0.101 | −1.300 *** | 0.338 | −0.109 |

| Family’s economic condition | 0.728 *** | 0.169 | 0.112 | 0.539 * | 0.216 | 0.064 |

| Academic performance | 0.747 *** | 0.086 | 0.228 | 0.060 | 0.112 | 0.014 |

| Bullying victimization | −0.414 *** | 0.027 | −0.407 | −0.295 *** | 0.037 | −0.224 |

| School belonging | 0.516 *** | 0.039 | 0.398 | |||

| Intercept | 20.235 *** | 1.834 | 10.576 *** | 2.445 | ||

| R2 | 0.306 | 0.340 | ||||

| F | 47.454 *** | 50.350 *** | ||||

| Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | Effect versus Total Effect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect (Bullying victimization → Mental health) | −0.2950 *** | 0.0372 | −0.3680 | −0.2220 | 58.0% |

| Indirect effect (Bullying victimization → School belonging → Mental health) | −0.2135 *** | 0.0249 | −0.2653 | −0.1674 | 42.0% |

| Total effect | −0.5085 *** | 0.0363 | −0.57973 | −0.4373 |

| Model 5 School Belonging | Model 6 Mental Health | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | S.E. | β | b | S.E. | β | |

| Male | 0.252 | 0.196 | 0.033 | 0.490 * | 0.244 | 0.050 |

| Age | −0.146 | 0.134 | −0.029 | −0.080 | 0.166 | −0.012 |

| Rural hukou | −0.297 | 0.234 | −0.033 | 0.444 | 0.291 | 0.038 |

| Only child status | 0.056 | 0.252 | 0.006 | 0.212 | 0.311 | 0.017 |

| Nanjing | 0.693 ** | 0.233 | 0.089 | 0.534 * | 0.295 | 0.053 |

| Number of school changes | −0.159 | 0.107 | −0.040 | 0.100 | 0.132 | 0.019 |

| Public school | −0.930 *** | 0.266 | −0.101 | 1.351 *** | 0.331 | −0.113 |

| Family’s economic condition | 0.728 *** | 0.169 | 0.112 | 0.454 * | 0.212 | 0.054 |

| Academic performance | 0.747 *** | 0.086 | 0.228 | −0.082 | 0.113 | −0.019 |

| Bullying victimization | −0.414 *** | 0.027 | −0.407 | −0.309 *** | 0.036 | −0.235 |

| School belonging | 0.707 *** | 0.120 | 0.546 | |||

| Resilience | 0.136 *** | 0.031 | 0.474 | |||

| School belonging × Resilience | −0.004 ** | 0.002 | −0.460 | |||

| Intercept | 20.235 *** | 1.834 | 4.578 | 3.130 | ||

| R2 | 0.306 | 0.369 | ||||

| F | 47.454 *** | 48.159 *** | ||||

| Moderator: Resilience | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low resilience (M − 1SD) | −0.1920 | 0.0264 | −0.2447 | −0.1406 |

| Medium resilience (M) | −0.1614 | 0.0229 | −0.2085 | −0.1178 |

| High resilience (M + 1SD) | −0.1308 | 0.0258 | −0.1841 | −0.0835 |

| Index | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilience | 0.0018 | 0.0007 | 0.0003 | 0.0032 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nie, W.; Gao, L.; Cui, K. Bullying Victimization and Mental Health among Migrant Children in Urban China: A Moderated Mediation Model of School Belonging and Resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127135

Nie W, Gao L, Cui K. Bullying Victimization and Mental Health among Migrant Children in Urban China: A Moderated Mediation Model of School Belonging and Resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):7135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127135

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Wei, Liru Gao, and Kunjie Cui. 2022. "Bullying Victimization and Mental Health among Migrant Children in Urban China: A Moderated Mediation Model of School Belonging and Resilience" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 7135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127135

APA StyleNie, W., Gao, L., & Cui, K. (2022). Bullying Victimization and Mental Health among Migrant Children in Urban China: A Moderated Mediation Model of School Belonging and Resilience. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7135. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127135