Forms of Community Engagement in Neighborhood Food Retail: Healthy Community Stores Case Study Project

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Recruitment and Data Collection

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

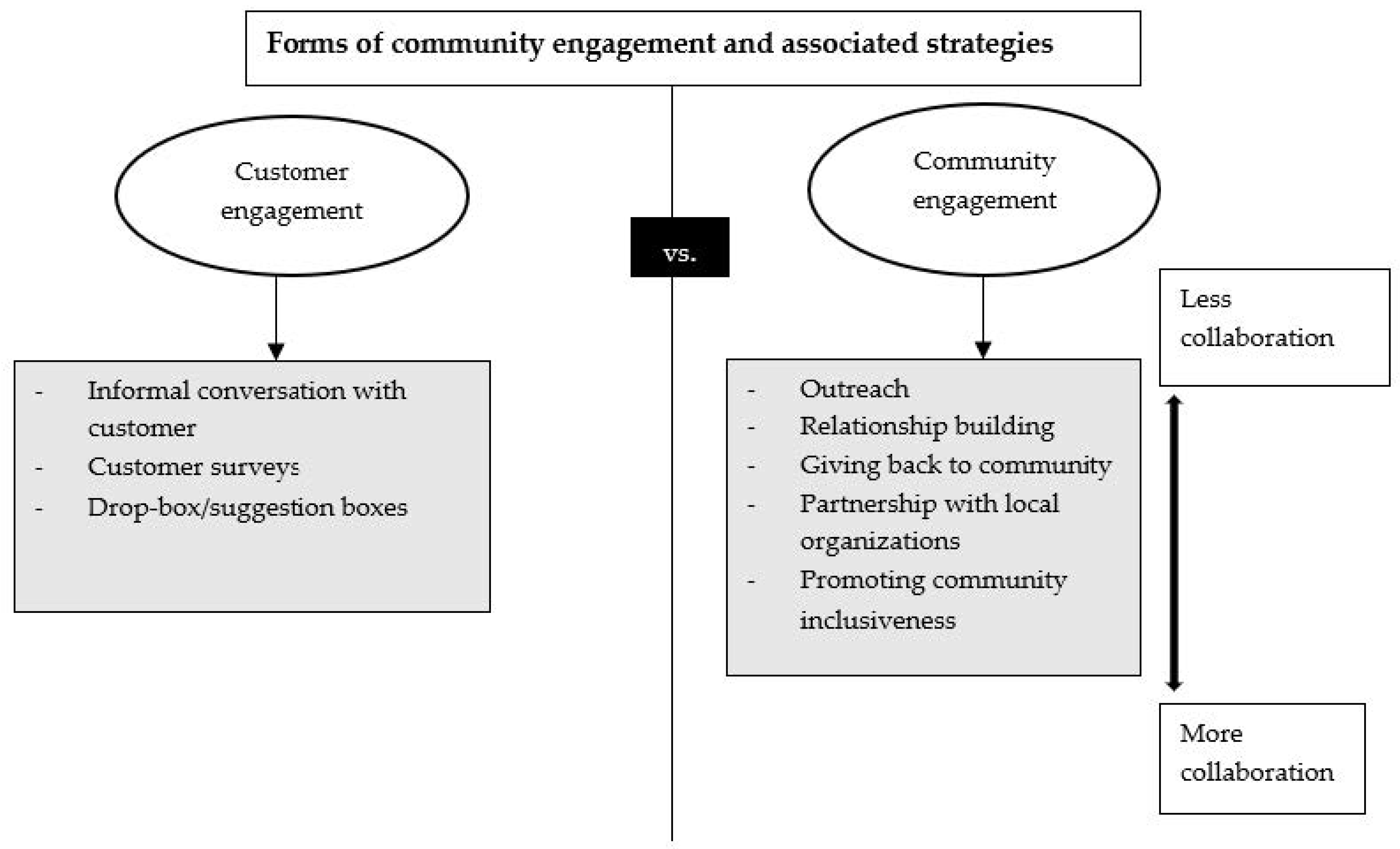

3.1. Customer Engagement vs. Community Engagement

3.2. Strategies of Community Engagement

3.2.1. Outreach

3.2.2. Relationship Building with Community through Customer Service and Relations

“Now you’re having a conversation human to human with your customer and it’s no longer this transactional relationship, but it becomes a neighbor-to-neighbor relationship.”[Washington, DC]

“It’s a church, it’s your local grocery store, it’s your confession center, your child center; this place is more than just fruits and vegetables. Some people just come in and don’t buy stuff; “they just want to come in and talk to us.”[Boston]

“People come to shop and do their grocery shopping, but I think what is unique about our grocery stores is that it’s a community gathering place…usually, it’s like people just hanging out in the aisles talking… We have people who hang out all day in our dining area. I think it’s a place where folks can just be in community.”[Minneapolis]

3.2.3. Giving Back to Community

“Our farmers need us to buy food so they don’t go out of business, your community members need food so they’re hungry; like, let’s figure this out. We’re ethically and morally aligned… and it really was wonderful, it really entrenched our relationship for the long term, that we’ll always have something going now.”[Washington, DC]

“The main reason I was thinking about it is because I want to do something to help foster newcomers in our community and then when the pandemic hit, hearing about how my people were struggling, I was like, this would be a great way to get money flowing with people in our community.”[Buffalo]

3.2.4. Partnering with Diverse Community Coalitions

“...it’s more than just a grocery store. It’s a statement of our values. It’s a commitment to sustainability in our environment and our food systems. It’s a commitment to support locally grown, locally produced food. It’s a commitment to shared ownership, a different way of being.”[Minneapolis]

“I feel like our relationship is a little bit different there. He’s constantly trying to expand his reach; he’s constantly trying to support more folks, whether it is through his store or just within the community. I think that’s unique to my relationship with them.”[Buffalo]

3.2.5. Promoting Community Inclusiveness and Representation

“Knowing and having…African American employees, where we are at, are predominantly in the African American community. [These employees] also have provided me input on what would be a product that we should carry.”[Chicago]

“There were people who said they didn’t, ‘We don’t even know why you were there,’ ‘We didn’t participate in you guys being there,’ ‘we didn’t understand it.’ They pointed to the fact that there are plenty of food sources [in the community] and so they had done their homework too and understood what our premise was for being there, what our mission was, and from their perspective it didn’t fit, so they most certainly didn’t shop there and were critical of our presence from that.”[Baltimore]

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seligman, H.K.; Laraia, B.A.; Kushel, M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J. Nutr. 2010, 140, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cooksey-Stowers, K.; Schwartz, M.B.; Brownell, K.D. Food swamps predict obesity rates better than food deserts in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cummins, S.; Flint, E.; Matthews, S.A. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elbel, B.; Moran, A.; Dixon, L.B.; Kiszko, K.; Cantor, J.; Abrams, C.; Mijanovich, T. Assessment of a government-subsidized supermarket in a high-need area on household food availability and children’s dietary intakes. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2881–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Community Engagement: Definitions and Organizing Concepts form literature. In Principles of Community Engagement, 2nd ed.; CDC/ATSDR Committee on Community Engagement: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Principles of Community Engagement, 1st ed.; CDC/ATSDR Committee on Community Engagement: Atlanta, GA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mara-Eves, A.; Brunton, G.; Oliver, S.; Kavanagh, J.; Jamal, F.; Thomas, J. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ross, H.; Baldwin, C.; Carter, R.W. Subtle implications: Public participation versus community engagement in environmental decision-making. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 23, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Minnesota Department of Health. Principle of Authentic Community Engagement. Available online: https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/resources/phqitoolbox/docs/AuthenticPrinciplesCommEng.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Cyril, S.; Smith, B.J.; Possamai-Inesedy, A.; Renzaho, A.M. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: A systematic review. Glob. Health Action 2015, 8, 29842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ortega, A.N.; Albert, S.L.; Sharif, M.Z.; Langellier, B.A.; Garcia, R.E.; Glik, D.C.; Brookmeyer, R.; Chan-Golston, A.M.; Friedlander, S.; Prelip, M.L. Proyecto MercadoFRESCO: A multi-level, community-engaged corner store intervention in East Los Angeles and Boyle Heights. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trinh-Shevrin, C.; Islam, N.; Tandon, S.D.; Abesamis, N.; Hoe-Asjoe, H.; Rey, M. Using community-based participatory research as a guiding framework for health disparities research centers. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2007, 1, 195. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler, M.; Vásquez, V.B.; Warner, J.R.; Steussey, H.; Facente, S. Sowing the seeds for sustainable change: A community-based participatory research partnership for health promotion in Indiana, USA and its aftermath. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holkup, P.A.; Tripp-Reimer, T.; Salois, E.M.; Weinert, C. Community-based participatory research: An approach to intervention research with a Native American community. ANS Adv. Nurs. Sci. 2004, 27, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balcazar, H.; Rosenthal, L.; De Heer, H.; Aguirre, M.; Flores, L.; Vasquez, E.; Duarte, M.; Schulz, L. Use of community-based participatory research to disseminate baseline results from a cardiovascular disease randomized community trial for Mexican Americans living in a US-Mexico border community. Educ. Health 2009, 22, 279. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B.A.; Schulz, A.J.; Parker, E.A.; Becker, A.B. Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rushakoff, J.A.; Zoughbie, D.E.; Bui, N.; DeVito, K.; Makarechi, L.; Kubo, H. Evaluation of Healthy2Go: A country store transformation project to improve the food environment and consumer choices in Appalachian Kentucky. Prev. Med. Rep. 2017, 7, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Donate, A.P.; Riggall, A.J.; Meinen, A.M.; Malecki, K.; Escaron, A.L.; Hall, B.; Menzies, A.; Garske, G.; Nieto, F.J.; Nitzke, S. Evaluation of a pilot healthy eating intervention in restaurants and food stores of a rural community: A randomized community trial. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shin, A.; Surkan, P.J.; Coutinho, A.J.; Suratkar, S.R.; Campbell, R.K.; Rowan, M.; Sharma, S.; Dennisuk, L.A.; Gass, A.; Gittelsohn, J. Impact of Baltimore Healthy Eating Zones: An environmental intervention to improve diet among African American youth. Health Educ. Behav. 2015, 42 (Suppl. S1), 97S–105S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Dyckman, W.; Frick, K.D.; Boggs, M.K.; Haberle, H.; Alfred, J.; Vastine, A.; Palafox, N. A pilot food store intervention in the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Pac. Health Dialog 2007, 14, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Kasprzak, C.M.; Hill, A.B.; Sundermeir, S.M.; Lska, M.N.; Dombrowski, R.D.; DeAngelo, J.; Odoms-Young, A.; Leone, L.A. Increasing healthy food access for low-income communities: Protocol of the Healthy Community Stores Case Study project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods; SAGE: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Multiple Case Study Analysis; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Community Catalyst. Strength in Numbers: A Guide to Building Community Coalitions. Available online: https://www.communitycatalyst.org/doc-store/publications/strength_in_numbers_a_guide_to_building_community_coalitions_aug03.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Zerafati-Shoae, N.; Jamshidi, E.; Salehi, L.; Taee, F.A. How to increase community participation capacity in food environment policymaking: Results of a scoping review. Med. J. Islamic Repub. Iran 2020, 34, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherell, R.; Cooper, C.; Peck, M. Sustainable Jobs, Sustainable Communities: The Union Co-op Model. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/The-Union-Co-op-Model-March-26-2012%20%283%29.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Berry, D.; Leopold, J.; Mahathey, A. Employee Ownership and Skill Development for Modest-Income Workers and Women. Available online: https://www.investinwork.org/-/media/Project/Atlanta/IAW/Files/volume-two/Employee-Ownership-and-Skill-Development-for-Modest-Income-Workers-and-Women.pdf (accessed on 7 April 2022).

- Tim, P. Worker Cooperative Industry Research Series. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/paper-palmer_0.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Rainbow Grocery Cooperative—A Worker-Owned Co-op. Available online: https://rainbow.coop/ (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Democracy at Work Institute. Becoming Employee Owned: A Small Business Toolkit for Transitioning to Employee Ownership. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/W2O%20-%20Becoming%20Employee%20Owned%20Toolkit.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- University of Wisconsin. Consumer Cooperatives. Available online: https://uwcc.wisc.edu/resources/consumer-cooperatives/ (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Food Co-op Initiative. The FCI Guide to Starting a Food Co-op. Available online: https://resources.uwcc.wisc.edu/Grocery/FCI-Startup-Guide.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Sharma, S.V.; Chow, J.; Pomeroy, M.; Raber, M.; Salako, D.; Markham, C. Lessons learned from the implementation of Brighter Bites: A food co-op to increase access to fruits and vegetables and nutrition education among low-income children and their families. J. Sch. Health 2017, 87, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakocs, R.C.; Edwards, E.M. What explains community coalition effectiveness?: A review of the literature. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, B.E.; Novotny, R.; Gittelsohn, J. Multi-level, multi-component approaches to community-based interventions for healthy living—A three case comparison. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dubowitz, T.; Ncube, C.; Leuschner, K.; Tharp-Gilliam, S. Capitalizing on a Natural Experiment Opportunity in Two Low-income Urban Food Desert Communities: Combining Scientific Rigor with Community Engagement. Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 2015, 42, 87S. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, H.S.; Franck, K.L.; Sweet, C.L. Community Coalitions for Change and the Policy, Systems, and Environment Model: A Community-Based Participatory Approach to Addressing Obesity in Rural Tennessee. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, 180678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mabachi, N.M.; Kimminau, K.S. Leveraging community-academic partnerships to improve healthy food access in an urban, Kansas City, Kansas, community. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. Res. Educ. Action 2012, 6, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, J.; Conde, P.; Sandin, M.; Urtasun, M.; López, R.; Carrero, J.L.; Gittelsohn, J.; Franco, M. Understanding the local food environment: A participatory photovoice project in a low-income area in Madrid, Spain. Health Place 2017, 43, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vásquez, V.B.; Lanza, D.; Hennessey-Lavery, S.; Facente, S.; Halpin, H.A.; Minkler, M. Addressing food security through public policy action in a community-based participatory research partnership. Health Promot. Pract. 2007, 8, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsui, E.; Bylander, K.; Cho, M.; Maybank, A.; Freudenberg, N. Engaging youth in food activism in New York City: Lessons learned from a youth organization, health department, and university partnership. J. Urban Health 2012, 89, 809–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, S.; Winkler, M.R.; Kaur, R.; DeAngelo, J.; Hill, A.B.; Sundermeir, S.M.; Gittelsohn, J. Balancing mission and margins: A multiple case study approach to identify what makes healthy community food stores successful. Inst. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022. under review. [Google Scholar]

| Baltimore, MD | Boston, MA | Buffalo, NY | Chicago, IL | Detroit, MI | Minneapolis, MN | Washington, DC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Customer engagement | |||||||

| Customer feedback (informal conversation/ survey/drop box) | ✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ |

| Community engagement | |||||||

| Listening sessions/focus groups | ✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ||

| Media usage | ✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | |

| Community coalitions 1 | ✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | |

| Participation in community events | ✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | |

| Hosting community events | ✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ |

| Community representation 2 | ✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔ | ✔✔ | ✔✔✔ | ✔✔✔ |

| ✔ = Only planned but not implemented ✔✔ = Planned and partially implemented ✔✔✔ = Planned and fully implemented 1. Community coalition refers to the partnerships the store had with other organizations in the community. 2. Community representation refers to the representation among the store staff and/or leadership team (either through employment or ownership). | |||||||

| Strategies | Definition | Example Activities | Case Sites with Evidence of the Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outreach | Using communication channels to inform communities regarding retailer events and activities | Media usage; annual reports | Boston (MA), Buffalo (NY), Detroit (MI), Minneapolis (MN), Washington (DC) |

| Relationship building with community through customer service and relations | Developing connections with customers to establish two-way information sharing among retailers and community members | Survey, drop box, focus groups, listening sessions, participation in community events | Boston (MA), Buffalo (NY), Chicago (IL), Detroit (MI), Minneapolis (MN), Washington (DC) |

| Giving back to community | Supporting community residents and local business to achieve their goals and enhance nutrition education | Hosting community events (e.g., cooking classes); donations to community organizations; prioritizing local vendors; workforce development programs | Boston (MA), Buffalo (NY), Chicago (IL), Detroit (MI), Minneapolis (MN), Washington (DC) |

| Partnering with diverse community coalitions | Building a partnership with different local community organizations to improve food access in the community | Community coalitions | Boston (MA), Buffalo (NY), Chicago (IL), Minneapolis (MN), Washington (DC) |

| Promoting community inclusiveness and representation in decision making | Having community members and/or representatives from the community participate in store decision making and future directions | Community representation in management/leadership/ownership; cooperative or social enterprise business model | Boston (MA), Minneapolis (MN), Washington (DC) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaur, R.; Winkler, M.R.; John, S.; DeAngelo, J.; Dombrowski, R.D.; Hickson, A.; Sundermeir, S.M.; Kasprzak, C.M.; Bode, B.; Hill, A.B.; et al. Forms of Community Engagement in Neighborhood Food Retail: Healthy Community Stores Case Study Project. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126986

Kaur R, Winkler MR, John S, DeAngelo J, Dombrowski RD, Hickson A, Sundermeir SM, Kasprzak CM, Bode B, Hill AB, et al. Forms of Community Engagement in Neighborhood Food Retail: Healthy Community Stores Case Study Project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(12):6986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126986

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaur, Ravneet, Megan R. Winkler, Sara John, Julia DeAngelo, Rachael D. Dombrowski, Ashley Hickson, Samantha M. Sundermeir, Christina M. Kasprzak, Bree Bode, Alex B. Hill, and et al. 2022. "Forms of Community Engagement in Neighborhood Food Retail: Healthy Community Stores Case Study Project" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 12: 6986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126986

APA StyleKaur, R., Winkler, M. R., John, S., DeAngelo, J., Dombrowski, R. D., Hickson, A., Sundermeir, S. M., Kasprzak, C. M., Bode, B., Hill, A. B., Lewis, E. C., Colon-Ramos, U., Munch, J., Witting, L. L., Odoms-Young, A., Gittelsohn, J., & Leone, L. A. (2022). Forms of Community Engagement in Neighborhood Food Retail: Healthy Community Stores Case Study Project. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 6986. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19126986