How Official Social Media Affected the Infodemic among Adults during the First Wave of COVID-19 in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

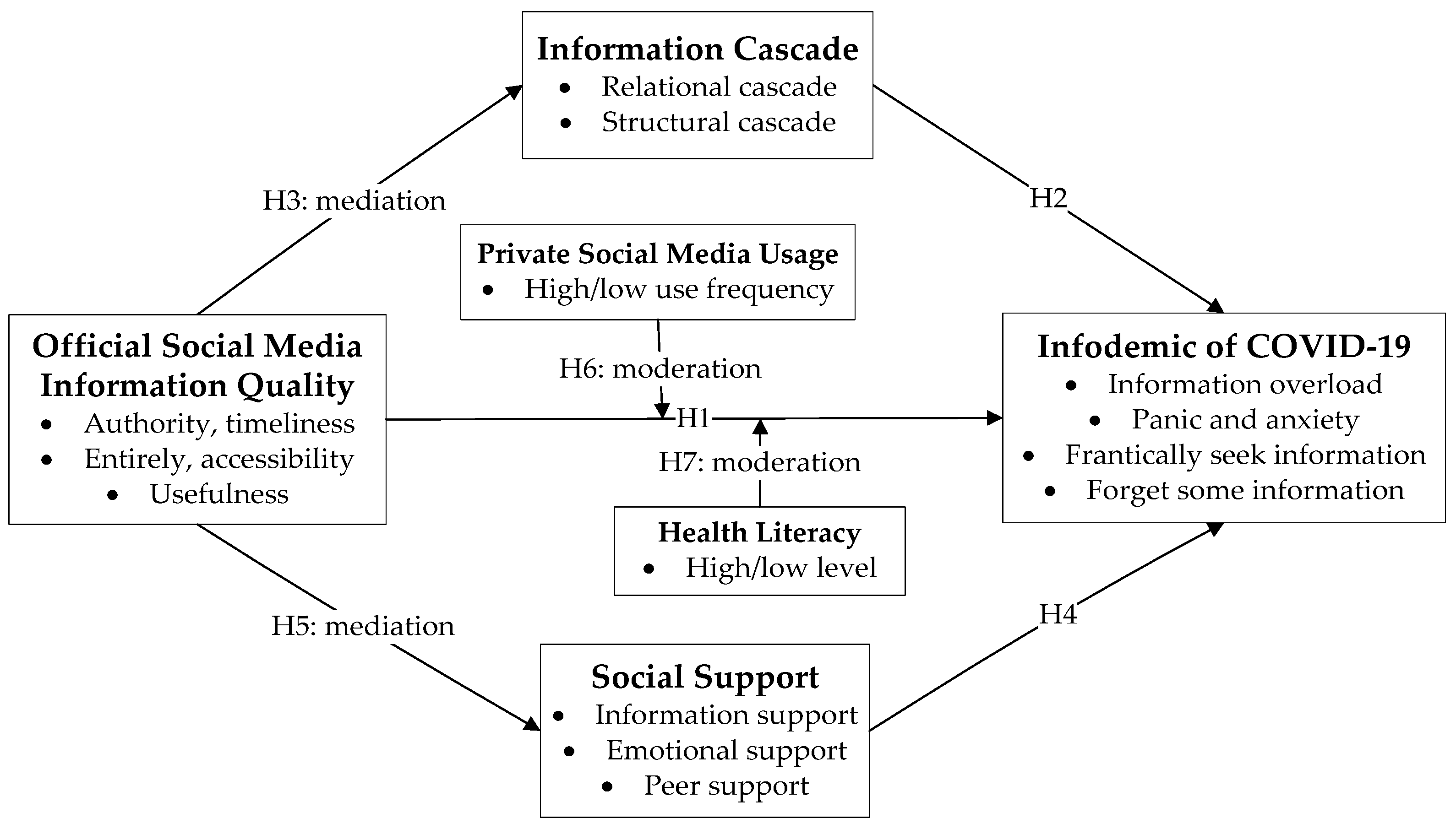

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Basis

2.2. Social Media in Public Health Crises (Official and Private) and the Infodemic

2.3. Information Cascades and the Infodemic

2.4. Social Support and the Infodemic

2.5. Mediation and Moderation Variables and the Infodemic

3. Methods

3.1. Questionnaire and Samples

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Information Quality (IQ) of Official Social Media Content

3.2.2. Social Support

3.2.3. Information Cascades

3.2.4. The COVID-19 Infodemic

3.3. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM)

4. Results

4.1. The Measurement Model

4.2. The Structural Model

4.2.1. Standardized Path Coefficient

4.2.2. Mediation Analysis

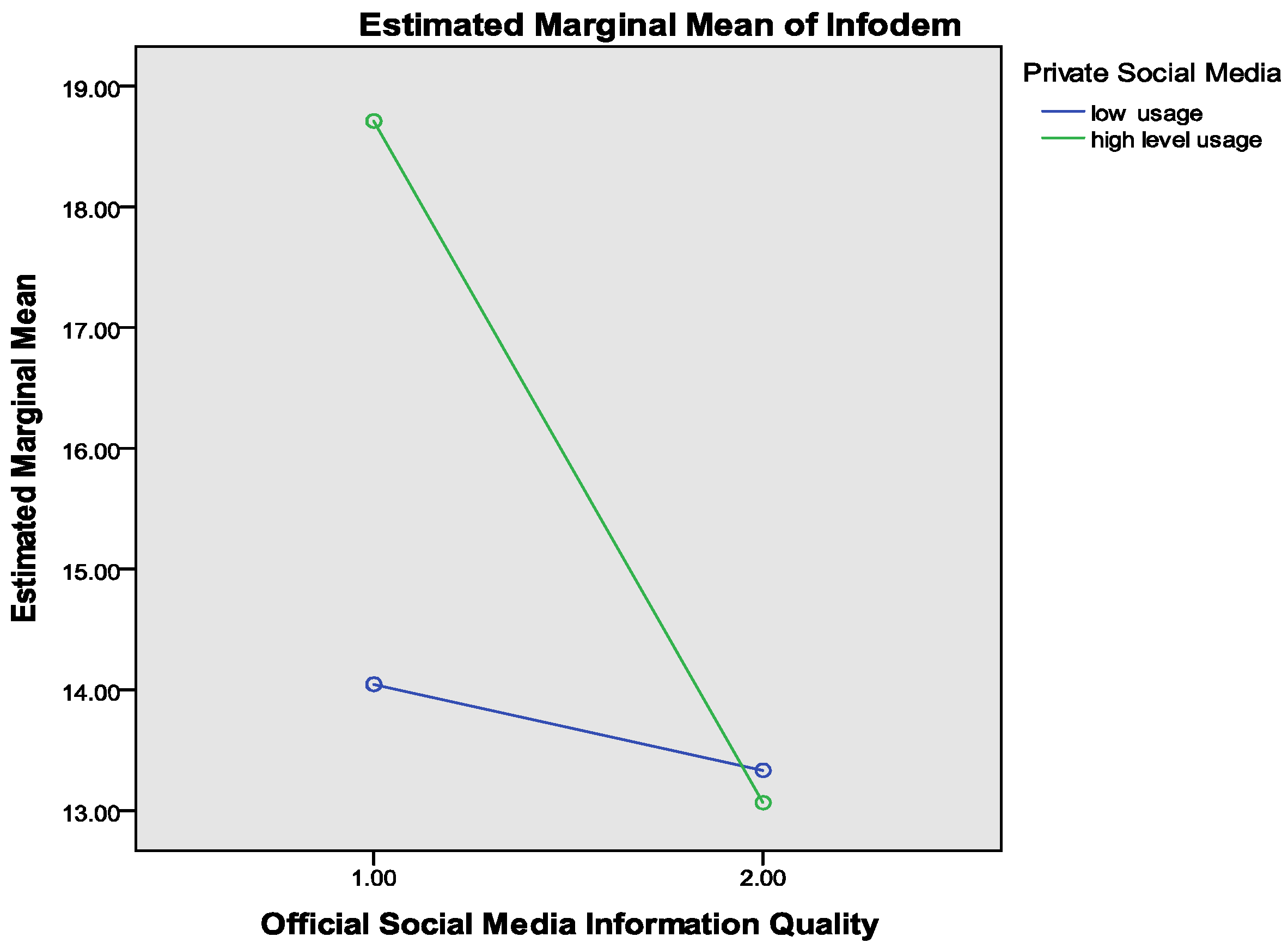

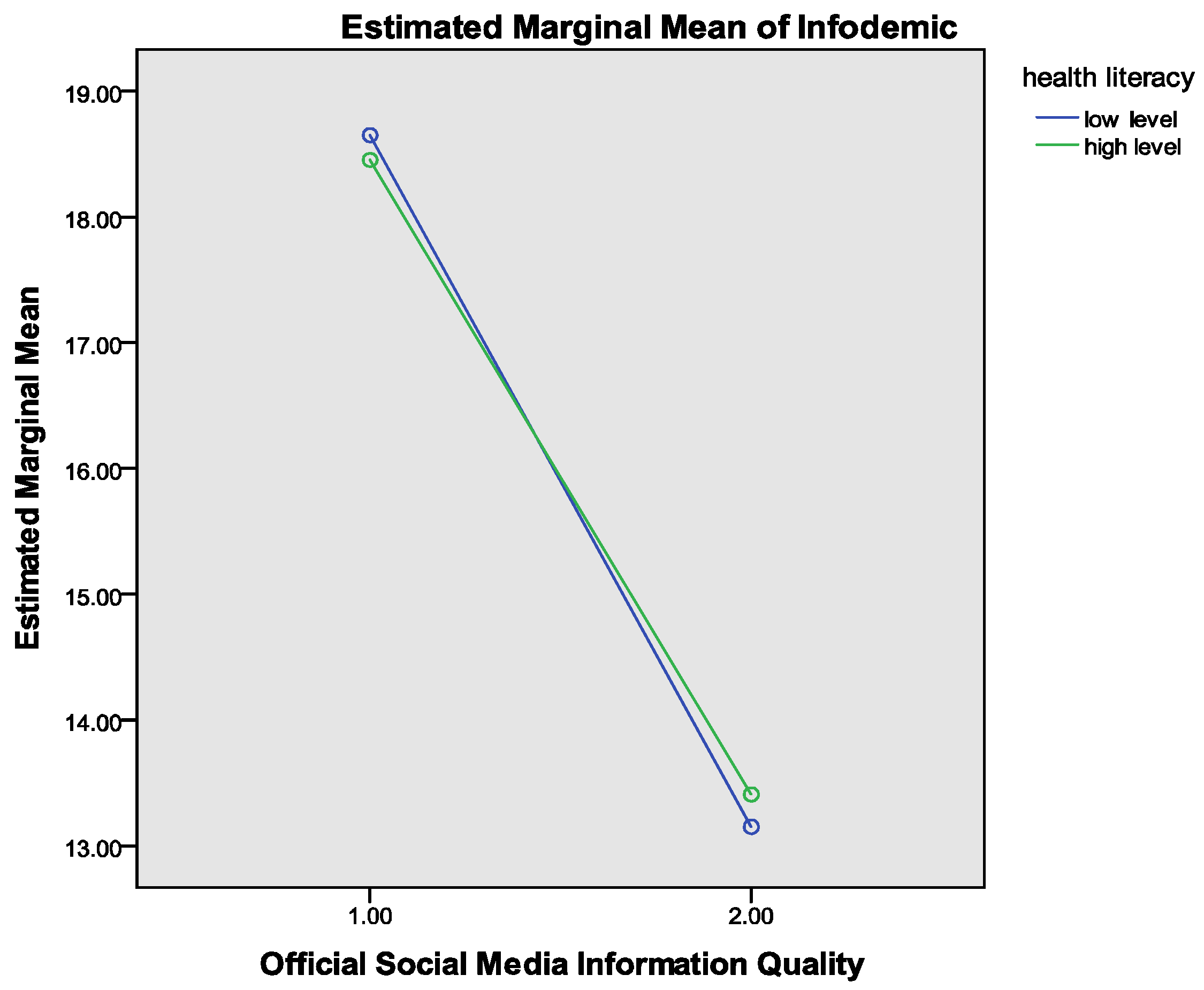

4.3. Moderating Analysis

4.4. Predict Partial Least Squares (PLS) Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Studies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pian, W.; Chi, J.; Ma, F. The causes, impacts and countermeasures of COVID-19 “Infodemic”: A systematic review using narrative synthesis. Inf. Process Manag. 2021, 58, 102713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Report-13. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330778 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Casero-Ripolles, A. Impact of COVID-19 on the media system. Communicative and democratic consequences of news consumption during the outbreak. Prof. Inf. 2020, 29, e290223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzd, A.; De Domenico, M.; Sacco, P.L.; Briand, S. Studying the COVID-19 infodemic at scale. Big Data Soc. 2021, 8, 205395172110211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, R.L.; Loftus, E.F. Pandemics and infodemics: Research on the effects of misinformation on memory. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, S.; Sarkar, T.; Khan, S.H.; Kamal, A.-H.M.; Hasan, S.M.M.; Kabir, A.; Yeasmin, D.; Islam, M.A.; Chowdhury, K.I.A.; Anwar, K.S.; et al. COVID-19—Related infodemic and its impact on public health: A global social media analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 1621–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongkhon, P.; Ruengorn, C.; Awiphan, R.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Nochaiwong, S. Exposure to COVID-19-Related information and its association with mental health problems in thailand: Nationwide, cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e25363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, J.; Xue, R.; Hu, J.; El Baz, D. Combating the infodemic: A chinese infodemic dataset for misinformation identification. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Xue, R.; Hu, J. COVID-19 infodemic on Chinese social media: A 4P framework, selective review and research directions. Meas. Control 2020, 53, 2070–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J.; Wang, D.; Su, Z.; Ziapour, A. The role of social media in the advent of COVID-19 pandemic: Crisis management, mental health challenges and implications. Risk Manag. Healthc. Policy 2021, 14, 1917–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adekoya, C.O.; Fasae, J.K. Social media and the spread of COVID-19 infodemic. Glob. Knowl. Mem. Commun. 2021, 71, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.W.; Connors, C.; Everly, J.G.S. COVID-19: Peer support and crisis communication strategies to promote institutional resilience. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020, 172, 822–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mheidly, N.; Fares, J. Leveraging media and health communication strategies to overcome the COVID-19 infodemic. J. Public Health Policy 2020, 41, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, M.L.; Taylor, M. Toward a dialogic theory of public relations. Public Relat. Rev. 2002, 28, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. Social media keep buzzing! A test of contingency theory in china’s red cross credibility crisis. Int. J. Commun. 2016, 10, 3241. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, F.M.; Camargo, C.Q. Autopsy of a metaphor: The origins, use and blind spots of the ‘infodemic’. New Media Soc. 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zheng, P.; Jia, Y.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Fu, H.; Dai, J. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231924. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, B.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Q. Mental health toll from the coronavirus: Social media usage reveals Wuhan residents’ depression and secondary trauma in the COVID-19 outbreak. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 114, 106524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.F.; Jin, Y.; Austin, L.L. The tendency to tell: Understanding publics’ communicative responses to crisis information form and source. J. Public Relat. Res. 2013, 25, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Fraustino, J.D.; Liu, B.F. The scared, the outraged, and the anxious: How crisis emotions, involvement, and demographics predict publics’ conative coping. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2016, 10, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, L.; Fisher Liu, B.; Jin, Y. How audiences seek out crisis information: Exploring the Social-Mediated crisis communication model. J. Appl. Commun. Res. 2012, 40, 188–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W.T. Academic research protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2007, 10, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Wei, Y. Social media peer communication and impacts on purchase intentions: A consumer socialization framework. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, B.F.; Austin, L.L. Examining the role of social media in effective crisis management. Commun. Res. 2014, 41, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, E.J. The role of source and the factors audiences rely on in evaluating credibility of health information. Public Relat. Rev. 2010, 36, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, S.B.; Bhatti, R.; Khan, A. An exploration of how fake news is taking over social media and putting public health at risk. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2021, 38, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, N.; Malviya, P.; Singh, P.; Mukherjee, S. Twitter mediated sociopolitical communication during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis in india. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 784907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B.; Seeger, M.W. Crisis and emergency risk communication as an integrative model. J. Health Commun. 2005, 10, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Q.; Min, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Evans, R. Unpacking the black box: How to promote citizen engagement through government social media during the COVID-19 crisis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Merrill Jr, K.; Collins, C.; Yang, H. Social TV viewing during the COVID-19 lockdown: The mediating role of social presence. Technol. Soc. 2021, 67, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, T. The changes in the effects of social media use of Cypriots due to COVID-19 pandemic. Technol. Soc. 2020, 63, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreassen, C.S.; Pallesen, S.; Griffiths, M.D. The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addict. Behav. 2017, 64, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Samal, J. Impact of COVID-19 infodemic on psychological wellbeing and vaccine hesitancy. Egypt. J. Bronchol. 2021, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashers, D.E.; Neidig, J.L.; Haas, S.M.; Dobbs, L.K.; Cardillo, L.W.; Russell, J.A. Communication in the management of uncertainty: The case of persons living with HIV or AIDS. Commun. Monogr. 2000, 67, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadaczynski, K.; Okan, O.; Messer, M.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Rosário, R.; Darlington, E.; Rathmann, K. Digital health literacy and Web-Based Information-Seeking behaviors of university students in germany during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e24097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Cheng, S.; Yu, X.; Xu, H. Chinese public’s attention to the COVID-19 epidemic on social media: Observational descriptive study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Ferraris, A. Factors influencing user participation in social media: Evidence from twitter usage during COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, P.L.; Gallotti, R.; Pilati, F.; Castaldo, N.; De Domenico, M. Emergence of knowledge communities and information centralization during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc. Sci. Med. 2021, 285, 114215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, D. Channel selection and knowledge acquisition during the 2009 Beijing H1N1 flu crisis a media system dependency theory perspective. Chin. J. Commun. 2014, 7, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, G.; Pan, J.; Roberts, M.E. How censorship in china allows government criticism but silences collective expression. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2013, 107, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, A.R.; Murad, H.R. The impact of social media on panic during the COVID-19 pandemic in iraqi kurdistan: Online questionnaire study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwok, L.; Lee, J.; Han, S.H. Crisis communication on social media: What types of COVID-19 messages get the attention? Cornell Hosp. Q. 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Chan, C. A cross-national diagnosis of infodemics: Comparing the topical and temporal features of misinformation around COVID-19 in China, India, the US, Germany and France. Online Inf. Rev. 2021, 45, 709–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Pian, W.; Ma, F.; Ni, Z.; Liu, Y. Characterizing the COVID-19 infodemic on chinese social media: Exploratory study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021, 7, e26090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enders, A.M.; Uscinski, J.E.; Klofstad, C.; Stoler, J. The different forms of COVID-19 misinformation and their consequences. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinf. Rev. 2020, 8, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.-K.; Wang, W.; Hou, D.; Xu, J.; Ye, X.; Li, S. Multiplex network reconstruction for the coupled spatial diffusion of infodemic and pandemic of COVID-19. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2021, 14, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; McDonnell, D.; Wen, J.; Kozak, M.; Abbas, J.; Šegalo, S.; Li, X.; Ahmad, J.; Cheshmehzangi, A.; Cai, Y.; et al. Mental health consequences of COVID-19 media coverage: The need for effective crisis communication practices. Glob. Health 2021, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickham, S.B.; Francis, D.B. The public’s perceptions of government officials’ communication in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Creat. Commun. 2021, 16, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhu, Q. An Overseas Review of the Spread of Opinions on Social Networks and Information Distortion Based on Information Cascade. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2019, 38, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman, C.K.; Singleton, L.C. Stigmatization in Childhood; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- White, L.K.; Suway, J.G.; Pine, D.S.; Bar-Haim, Y.; Fox, N.A. Cascading effects: The influence of attention bias to threat on the interpretation of ambiguous information. Behav. Res. Ther. 2011, 49, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lansford, J.E.; Malone, P.S.; Dodge, K.A.; Pettit, G.S.; Bates, J.E. Developmental cascades of peer rejection, social information processing biases, and aggression during middle childhood. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010, 22, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vismara, S. Information Cascades among Investors in Equity Crowdfunding. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 467–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, S.; Zhang, L. The influence of information cascades on online purchase behaviors of search and experience products. Electron. Commer. Res. 2016, 16, 553–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, T.R.; Mendelson, T.; Robins, C.J.; Krishnan, K.R.; George, L.K.; Johnson, C.S.; Blazer, D.G. Perceived social support among depressed elderly, middle-aged, and young-adult samples: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. J. Affect. Disord. 1999, 55, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.H.; Petrie, K.J. Social Support and Recovery from Disease and Medical Procedures. Int. Encycl. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2001, 55, 14458–14461. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, N.; Ensel, W.M.; Simeone, R.S.; Kuo, W. Social support, stressful life events, and illness: A model and an empirical test. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1979, 20, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, M.Y.; Yang, L.; Leung, C.M.C.; Li, N.; Yao, X.I.; Wang, Y.; Leung, G.M.; Cowling, B.J.; Liao, Q. Mental health, risk factors, and social media use during the COVID-19 epidemic and cordon sanitaire among the community and health professionals in wuhan, china: Cross-Sectional survey. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.; Zhou, S.-J.; Guo, Z.-C.; Zhang, L.-G.; Min, H.-J.; Li, X.-M.; Chen, J.-X. The effect of social support on mental health in chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. J. Adolesc. Health 2020, 67, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grey, I.; Arora, T.; Thomas, J.; Saneh, A.; Tohme, P.; Abi-Habib, R. The role of perceived social support on depression and sleep during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiat. Res. 2020, 293, 113452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groarke, J.M.; Berry, E.; Graham-Wisener, L.; Mckenna-Plumley, P.E.; Mcglinchey, E.; Armour, C. Loneliness in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional results from the COVID-19 Psychological Wellbeing Study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, V.; Ng, K.S.; Rahim, H.A. To share or not to share—The underlying motives of sharing fake news amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. Technol. Soc. 2021, 66, 101676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Laato, S.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Isoaho, J. Understanding the impact of information sources on COVID-19 related preventive measures in Finland. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paakkari, L.; Okan, O. COVID-19: Health literacy is an underestimated problem. Lancet Public Health 2020, 5, e249–e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, K.; Cvejic, E.; Nickel, B.; Copp, T.; Bonner, C.; Leask, J.; Ayre, J.; Batcup, C.; Cornell, S.; Dakin, T.; et al. COVID-19 misinformation trends in australia: Prospective longitudinal national survey. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovee, M.; Srivastava, R.P.; Mak, B. A conceptual framework and belief-function approach to assessing overall information quality. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2003, 18, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jayasinghe, R.; Ranasinghe, S.; Jayarajah, U.; Seneviratne, S. Quality of online information for the general public on COVID-19. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2594–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor-Phillips, S.; Berhane, S.; Sitch, A.J.; Freeman, K.; Price, M.J.; Davenport, C.; Geppert, J.; Harris, I.M.; Osokogu, O.; Skrybant, M.; et al. Information given by websites selling home self-sampling COVID-19 tests: An analysis of accuracy and completeness. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e042453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okike, B.I. Information dissemination in an era of a pandemic (COVID-19): Librarians’ role. Libr. Hi Tech News 2020, 37, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Meredith, R.; Burstein, F. A data quality framework, method and tools for managing data quality in a health care setting: An action case study. J. Decis. Syst. 2018, 27, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.Y.; Strong, D.M. Beyond accuracy: What data quality means to data consumers. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 1996, 12, 5–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Cai, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, N. Development and validation of an instrument to measure user perceived service quality of information presenting Web portals. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 575–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Official social media and its impact on public behavior during the first wave of COVID-19 in China. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Zhong, B.; Kumar, A.; Chow, S.; Ouyang, A. Exchanging social support online a longitudinal social network analysis of irritable bowel syndrome patients’ interactions on a health forum. J. Mass Commun. Q. 2018, 95, 1033–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Xia, G.; Pang, P.; Wu, B.; Jiang, W.; Li, Y.-T.; Wang, M.; Ling, Q.; Chang, X.; Wang, J.; et al. COVID-19 epidemic peer support and crisis intervention via social media. Community Ment. Health J. 2020, 56, 786–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S.; Hirshleifer, D.; Welch, I. A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change as informational cascades. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 992–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, Z.; Yi, L.; N, K.S.; Qu, H.; Ma, X. WeSeer: Visual analysis for better information cascade prediction of WeChat articles. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2020, 26, 1399–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, C. Emotion diffusion, information cascades, and internet opinion deviation: A dynamic analysis based on emergency events panel data from 2015 to 2020. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2021, 40, 448–461. [Google Scholar]

- Misra, S.; Stokols, D. Psychological and health outcomes of perceived information overload. Environ. Behav. 2011, 44, 737–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Plann. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partical least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alin, A.; Kurt, S. Testing non-additivity (interaction) in two-way ANOVA tables with no replication. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2006, 15, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Ray, S.; Velasquez Estrada, J.M.; Chatla, S.B. The elephant in the room: Predictive performance of PLS models. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4552–4564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, C. Infodemic vs. Pandemic factors associated to public anxiety in the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak: A Cross-Sectional study in china. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 723648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopory, P.; Day, A.M.; Novak, J.M.; Eckert, K.; Wilkins, L.; Padgett, D.R.; Noyes, J.P.; Barakji, F.A.; Liu, J.; Fowler, B.N.; et al. Communicating uncertainty during public health emergency events: A systematic review. Rev. Commun. Res. 2019, 7, 67–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-García, I.; Giménez-Júlvez, T. Assessment of health information about COVID-19 prevention on the internet: Infodemiological study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, e18717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shim, M.; Jo, H.S. What quality factors matter in enhancing the perceived benefits of online health information sites? Application of the updated DeLone and McLean Information Systems Success Model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2020, 137, 104093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hua, J.; Shaw, R. Corona virus (COVID-19) “infodemic” and emerging issues through a data lens: The case of china. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Naeem, S.B.; Bhatti, R. The COVID-19 ‘infodemic’: A new front for information professionals. Health Inf. Libr. J. 2020, 37, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallè, F.; Sabella, E.A.; Roma, P.; Ferracuti, S.; Da Molin, G.; Diella, G.; Montagna, M.T.; Orsi, G.B.; Liguori, G.; Napoli, C. Knowledge and Lifestyle Behaviors Related to COVID-19 Pandemic in People over 65 Years Old from Southern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Linden, S.; Roozenbeek, J.; Compton, J. Inoculating against fake news about COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Category | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 685 | 49.0% |

| Female | 713 | 51.0% | |

| Age | 18–30 years old | 323 | 23.1% |

| 31–40 years old | 504 | 36.1% | |

| 41–50 years old | 375 | 26.8% | |

| 51–60 years old | 128 | 9.2% | |

| More than 60 years old | 68 | 4.9% | |

| Education | Junior school or below | 120 | 8.5% |

| Senior high school | 176 | 12.6% | |

| Associate degree | 564 | 40.3% | |

| Bachelor degree | 433 | 31.0% | |

| Master’s degree or Ph.D. | 105 | 7.5% | |

| Annual Household Income (Chinese yuan) | Less than 30,000 | 37 | 2.6% |

| 30,000–100,000 | 825 | 59% | |

| 110,000–200,000 | 388 | 27.8% | |

| More than 200,000 | 148 | 10.6% |

| Cronbach’s α | Rho_A | CR | AVE | VIF Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infodemic | 0.773 | 0.786 | 0.847 | 0.527 | 1.28–01.665 |

| Information Cascades | 0.732 | 0.740 | 0.833 | 0.555 | 1.328–1.540 |

| Information Quality | 0.820 | 0.824 | 0.874 | 0.582 | 1.458–1.716 |

| Support | 0.880 | 0.881 | 0.907 | 0.582 | 1.650–2.068 |

| Quality | Cascades | Support | Infodemic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Quality | 0.763 | |||

| Information Cascades | −0.590 ** | 0.745 | ||

| Support | 0.660 ** | −0.612 ** | 0.763 | |

| Infodemic | −0.558 ** | 0.573 ** | −0.555 ** | 0.726 |

| Path | O.S. | Sample | S.D. | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cascades → Infodemic | 0.242 | 0.243 | 0.029 | 8.366 | 0.000 |

| Quality → Infodemic | −0.294 | −0.293 | 0.036 | 8.111 | 0.000 |

| Quality → Cascades | −0.782 | −0.782 | 0.012 | 63.292 | 0.000 |

| Quality → Support | 0.861 | 0.861 | 0.008 | 107.155 | 0.000 |

| Support → Infodemic | −0.387 | −0.388 | 0.036 | 10.664 | 0.000 |

| PLS-SEM | LM Benchmark | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | MAE | Q2_Predict | RMSE | MAE | Q2_Predict | |

| overstretched | 1.018 | 0.793 | 0.401 | 1.013 | 0.787 | 0.408 |

| forgotten | 1.009 | 0.839 | 0.351 | 1.010 | 0.839 | 0.349 |

| refresh | 1.000 | 0.851 | 0.245 | 1.001 | 0.852 | 0.242 |

| anxiety | 0.935 | 0.745 | 0.466 | 0.934 | 0.743 | 0.466 |

| difficult | 1.011 | 0.790 | 0.282 | 1.014 | 0.795 | 0.277 |

| Relation cascades1 | 1.063 | 0.898 | 0.296 | 1.066 | 0.900 | 0.292 |

| Structural cascades2 | 1.019 | 0.831 | 0.317 | 1.020 | 0.830 | 0.315 |

| Structural cascades1 | 1.047 | 0.873 | 0.307 | 1.050 | 0.874 | 0.302 |

| Relation cascades2 | 0.943 | 0.747 | 0.432 | 0.946 | 0.749 | 0.428 |

| Study knowledge | 0.955 | 0.723 | 0.391 | 0.958 | 0.724 | 0.388 |

| Alleviate loneliness | 0.915 | 0.721 | 0.450 | 0.918 | 0.722 | 0.446 |

| Reduce worry | 0.952 | 0.742 | 0.461 | 0.953 | 0.740 | 0.460 |

| Prefer official | 0.929 | 0.715 | 0.418 | 0.930 | 0.717 | 0.416 |

| Share advice | 0.949 | 0.735 | 0.386 | 0.952 | 0.738 | 0.382 |

| Manage press | 0.915 | 0.723 | 0.474 | 0.915 | 0.723 | 0.474 |

| Read experience | 0.917 | 0.713 | 0.427 | 0.915 | 0.709 | 0.430 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Chen, Q.; Evans, R. How Official Social Media Affected the Infodemic among Adults during the First Wave of COVID-19 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116751

Liu H, Chen Q, Evans R. How Official Social Media Affected the Infodemic among Adults during the First Wave of COVID-19 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(11):6751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116751

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Huan, Qiang Chen, and Richard Evans. 2022. "How Official Social Media Affected the Infodemic among Adults during the First Wave of COVID-19 in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 11: 6751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116751

APA StyleLiu, H., Chen, Q., & Evans, R. (2022). How Official Social Media Affected the Infodemic among Adults during the First Wave of COVID-19 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6751. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116751