Parent Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Outcomes from the Translational ‘Time for Healthy Habits’ Trial: Secondary Outcomes from a Partially Randomized Preference Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

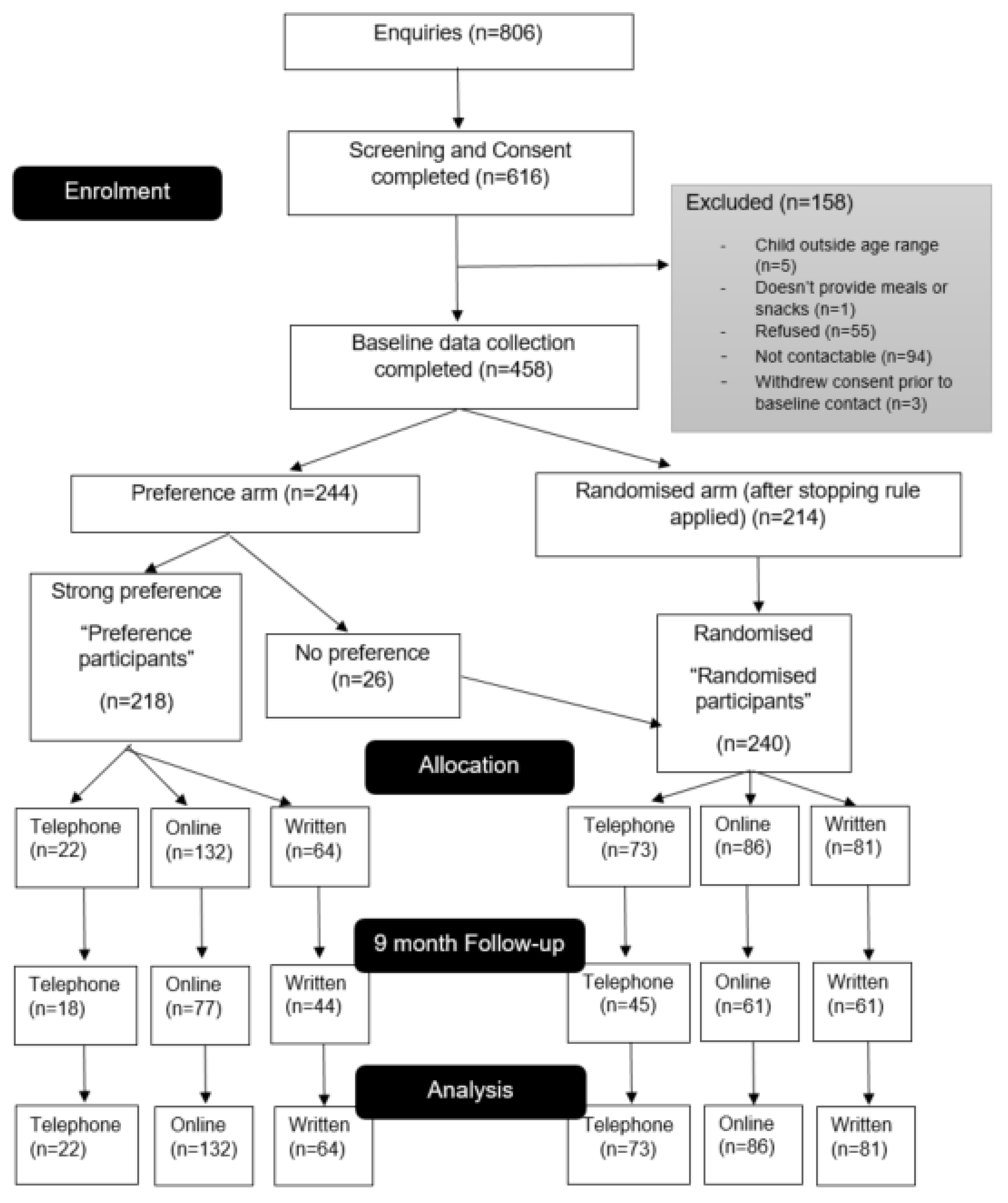

2.1. Study Sample

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Interventions

2.4. Control Group

2.5. Data Collection and Measures

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Vegetable Consumption

3.2. Fruit Consumption

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, R.H. Health benefits of fruit and vegetables are from additive and synergistic combinations of phytochemicals. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 517S–520S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinton, S.K.; Giovannucci, E.L.; Hursting, S.D. The world cancer research fund/American institute for cancer research third expert report on diet, nutrition, physical activity, and cancer: Impact and future directions. J. Nutr. 2019, 150, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poorolajal, J.; Moradi, L.; Mohammadi, Y.; Cheraghi, Z.; Gohari-Ensaf, F. Risk factors for stomach cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiol. Health 2020, 42, e2020004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aune, D.; Giovannucci, E.; Boffetta, P.; Fadnes, L.T.; Keum, N.; Norat, T.; Greenwood, D.C.; Riboli, E.; Vatten, L.J.; Tonstad, S. Fruit and vegetable intake and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer and all-cause mortality—A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 46, 1029–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurbau, A.; Au-Yeung, F.; Blanco Mejia, S.; Khan, T.A.; Vuksan, V.; Jovanovski, E.; Leiter, L.A.; Kendall, C.W.; Jenkins, D.J.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Relation of different fruit and vegetable sources with incident cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta—Analysis of prospective cohort studies. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e017728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases: Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003; Volume 916. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nores, M.; Barnett, W.S. Benefits of early childhood interventions across the world: (Under) investing in the very young. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2010, 29, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, P.R.; Lye, S.J.; Proulx, K.; Yousafzai, A.K.; Matthews, S.G.; Vaivada, T.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Rao, N.; Ip, P.; Fernald, L.C. Nurturing care: Promoting early childhood development. Lancet 2017, 389, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkilä, V.; Räsänen, L.; Raitakari, O.T.; Pietinen, P.; Viikari, J. Consistent dietary patterns identified from childhood to adulthood: The cardiovascular risk in young finns study. Br. J. Nutr. 2005, 93, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demory-Luce, D.; Morales, M.; Nicklas, T.; Baranowski, T.; Zakeri, I.; Berenson, G. Changes in food group consumption patterns from childhood to young adulthood: The bogalusa heart study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 1684–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassagh, E.Z.; Baxter-Jones, A.D.G.; Kontulainen, S.; Whiting, S.J.; Vatanparast, H. Tracking dietary patterns over 20 years from childhood through adolescence into young adulthood: The saskatchewan pediatric bone mineral accrual study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenkranz, R.R.; Dzewaltowski, D.A. Model of the home food environment pertaining to childhood obesity. Nutr. Rev. 2008, 66, 123–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Horst, K.; Oenema, A.; Ferreira, I.; Wendel-Vos, W.; Giskes, K.; van Lenthe, F.; Brug, J. A systematic review of environmental correlates of obesity-related dietary behaviors in youth. Health Educ. Res. 2006, 22, 203–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touyz, L.M.; Wakefield, C.E.; Grech, A.M.; Quinn, V.F.; Costa, D.S.J.; Zhang, F.F.; Cohn, R.J.; Sajeev, M.; Cohen, J. Parent-targeted home-based interventions for increasing fruit and vegetable intake in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, A.; Fox, C.; Bauerly, K.; Gross, A.; Heim, C.; Judge-Dietz, J.; Webb, B. Prevention and Management of Obesity for Children and Adolescents; Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI): Bloomington, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes-Robison, C.; Evans, R.R. Benefits and barriers to medically supervised pediatric weight-management programs. J. Child Health Care 2008, 12, 329–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.M.; Golley, R.K.; Collins, C.E.; Okely, A.D.; Jones, R.A.; Morgan, P.J.; Perry, R.A.; Baur, L.A.; Steele, J.R.; Magarey, A.M. Randomised controlled trials in overweight children: Practicalities and realities. Int. J. Pediatric Obes. 2007, 2, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomerleau, J.; Lock, K.; Knai, C.; McKee, M. Interventions designed to increase adult fruit and vegetable intake can be effective: A systematic review of the literature. J. Nutr. 2005, 135, 2486–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.T.; Reidlinger, D.P.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Campbell, K.L. Telehealth methods to deliver dietary interventions in adults with chronic disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, M.; Kaufman, V.; Shahar, D.R. Childhood obesity treatment: Targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. Br. J. Nutr. 2006, 95, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, N.; Biddle, S.J.; Gorely, T. Family correlates of fruit and vegetable consumption in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draxten, M.; Fulkerson, J.A.; Friend, S.; Flattum, C.F.; Schow, R. Parental role modeling of fruits and vegetables at meals and snacks is associated with children’s adequate consumption. Appetite 2014, 78, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groele, B.; Głąbska, D.; Gutkowska, K.; Guzek, D. Mothers’ vegetable consumption behaviors and preferences as factors limiting the possibility of increasing vegetable consumption in children in a national sample of polish and Romanian respondents. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haire-Joshu, D.; Elliott, M.B.; Caito, N.M.; Hessler, K.; Nanney, M.; Hale, N.; Boehmer, T.K.; Kreuter, M.; Brownson, R.C. High 5 for Kids: The impact of a home visiting program on fruit and vegetable intake of parents and their preschool children. Prev. Med. 2008, 47, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyse, R.; Campbell, K.J.; Brennan, L.; Wolfenden, L. A cluster randomised controlled trial of a telephone-based intervention targeting the home food environment of preschoolers (The Healthy Habits Trial): The effect on parent fruit and vegetable consumption. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wolfenden, L.; Wyse, R.; Campbell, E.; Brennan, L.; Campbell, K.J.; Fletcher, A.; Wiggers, J.; Bowman, J.; Heard, T.R. Randomized controlled trial of a telephone-based intervention for child fruit and vegetable intake: Long-term follow-up. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 99, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammersley, M.L.; Okely, A.D.; Batterham, M.J.; Jones, R.A. An internet-based childhood obesity prevention program (Time2bHealthy) for parents of preschool-aged children: Randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e11964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, M.L.; Wyse, R.J.; Jones, R.A.; Wolfenden, L.; Yoong, S.; Stacey, F.; Eckermann, S.; Okely, A.D.; Innes-Hughes, C.; Li, V. Translation of two healthy eating and active living support programs for parents of 2–6 year old children: A parallel partially randomised preference trial protocol (the ‘time for healthy habits’ trial). BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasmann, K.A.; Wijsman, P.; van Dieren, S.; Bemelman, W.; Buskens, C. Partially randomised patient preference trials as an alternative design to randomised controlled trials: Systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e031151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, M.L.; Wyse, R.J.; Jones, R.A.; Stacey, F.; Okely, A.D.; Wolfenden, L.; Batterham, M.J.; Yoong, S.; Eckermann, S.; Green, A. Translation of Two Healthy Eating and Active Living Support Programs for Parents of 2–6-Year-Old Children: Outcomes of the ‘Time for Healthy Habits’ Parallel Partially Randomised Preference Trial. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, T. Applying the socio-ecological model to improving fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African Americans. J. Community Health 2008, 33, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, M.; Weizman, A. Familial approach to the treatment of childhood obesity: Conceptual model. J. Nutr. Educ. 2001, 33, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Government. NSW Population Health Survey 2018 Questionnaire; NSW Government: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4363.0—National Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2017–2018. Available online: https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/4363.0~2017-18~Main%20Features~Fruit%20and%20vegetable%20consumption~42 (accessed on 11 May 2021).

- Coyne, T.; Ibiebele, T.I.; McNaughton, S.; Rutishauser, I.H.; O’Dea, K.; Hodge, A.M.; McClintock, C.; Findlay, M.G.; Lee, A. Evaluation of brief dietary questions to estimate vegetable and fruit consumption–using serum carotenoids and red-cell folate. Public Health Nutr. 2005, 8, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadowski, A.M.; McCaffrey, T.A.; Heritier, S.; Curtis, A.J.; Nanayakkara, N.; Zoungas, S.; Owen, A.J. Development, relative validity and reproducibility of the Aus-SDS (Australian short dietary screener) in adults aged 70 years and above. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy-Byrne, P.P.; Sherbourne, C.D.; Craske, M.G.; Stein, M.B.; Katon, W.; Sullivan, G.; Means-Christensen, A.; Bystritsky, A. Moving treatment research from clinical trials to the real world. Psychiatr. Serv. 2003, 54, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch, M.; Jones, J.; Yoong, S.; Wiggers, J.; Wolfenden, L. Effectiveness of centre-based childcare interventions in increasing child physical activity: A systematic review and meta-analysis of policymakers and practitioners. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoong, S.L.; Wolfenden, L.; Clinton-McHarg, T.; Waters, E.; Pettman, T.L.; Steele, E.; Wiggers, J. Exploring the pragmatic and explanatory study design on outcomes of systematic reviews of public health interventions: A case study on obesity prevention trials. J. Public Health 2014, 36, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Australian Institute of Health Welfare. Poor Diet; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, W.; Nigg, C.R.; Pagano, I.S.; Motl, R.W.; Horwath, C.; Dishman, R.K. Associations of quality of life with physical activity, fruit and vegetable consumption, and physical inactivity in a free living, multiethnic population in Hawaii: A longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couper, M.P.; Alexander, G.L.; Zhang, N.; Little, R.J.; Maddy, N.; Nowak, M.A.; McClure, J.B.; Calvi, J.J.; Rolnick, S.J.; Stopponi, M.A.; et al. Engagement and retention: Measuring breadth and depth of participant use of an online intervention. J. Med. Internet Res. 2010, 12, e1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goode, A.D.; Reeves, M.M.; Eakin, E.G. Telephone-delivered interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: An updated systematic review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012, 42, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.G.; Worsley, A.; Liem, D.G. Parents’ food choice motives and their associations with children’s food preferences. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglioni, S.; Salvioni, M.; Galimberti, C. Influence of parental attitudes in the development of children eating behaviour. Br. J. Nutr. 2008, 99, S22–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holley, C.E.; Haycraft, E.; Farrow, C. ‘Why don’t you try it again?’A comparison of parent led, home based interventions aimed at increasing children’s consumption of a disliked vegetable. Appetite 2015, 87, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Intervention | Telephone Intervention (Healthy Habits Plus) | Online Intervention (Time2bHealthy) |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery Mode |

|

|

| Intervention Components |

|

|

| Intervention Content | Both programs sought to improve healthy eating and movement behaviors (physical activity, sedentary screen time and sleep), and focused on:

| |

| Adherence Strategies |

|

|

| Randomized Participants (n = 240) | Preference Participants (n = 218) | ALL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone | Online | Written Control | Telephone | Online | Written Control | ||

| n = 73 | n = 86 | n = 81 | n = 22 | n = 132 | n = 64 | n = 458 | |

| Age, in years | |||||||

| Mean | 34.9 | 36.6 | 36.8 | 37.2 | 36.1 | 35.8 | 36.1 |

| SD | 4.5 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 4.9 |

| Sex—female | |||||||

| N | 69 | 83 | 79 | 22 | 126 | 62 | 441 |

| % | 94.5 | 96.5 | 97.5 | 100 | 95.5 | 96.9 | 96.3 |

| University-educated | |||||||

| N | 57 | 64 | 53 | 20 | 88 | 40 | 322 |

| % | 78.1 | 74.4 | 65.4 | 90.9 | 66.7 | 62.5 | 70.3 |

| Annual household income > AUD 100,000 | |||||||

| N | 49 | 58 | 57 | 16 | 91 | 40 | 311 |

| % | 67.1 | 69.0 | 71.3 | 72.7 | 68.9 | 62.5 | 68.3 |

| Baseline Intake | Follow-Up Intake | Complete Case Analysis a | Multiple Imputation Analysis b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean Difference vs. Control (95% CI), p-Value | Mean Difference vs. Control (95% CI), p-Value | |

| Randomized participants | ||||

| Telephone intervention (n = 73) | 3.12 (1.89) | 3.58 (1.37) | 0.48 (0.07, 0.88), p = 0.02 | 0.41 (0.02, 0.81), p = 0.04 |

| Online intervention (n = 86) | 2.88 (1.44) | 3.20 (1.53) | 0.24 (−0.13, 0.61), p = 0.20 | 0.24 (−0.13, 0.61), p = 0.21 |

| Written control (n = 81) | 3.23 (1.65) | 3.02 (1.20) | Reference | Reference |

| Preference participants | ||||

| Telephone intervention (n = 22) | 2.36 (1.14) | 2.50 (1.15) | −0.19 (−0.77, 0.38), p = 0.51 | −0.14 (−0.70, 0.42), p = 0.62 |

| Online intervention (n = 132) | 3.05 (1.41) | 3.23 (1.28) | 0.05 (−0.34, 0.44), p = 0.80 | 0.11 (−0.26, 0.48), p = 0.56 |

| Written control (n = 64) | 2.78 (1.31) | 2.91 (1.44) | Reference | Reference |

| All participants | ||||

| Telephone intervention (n = 95) | 2.94 (1.77) | 3.25 (1.39) | 0.27 (−0.06, 0.60), p = 0.11 | 0.27 (−0.06, 0.60), p = 0.1 |

| Online intervention (n = 218) | 2.98 (1.42) | 3.22 (1.42) | 0.15 (−0.12, 0.42), p = 0.26 | 0.17 (−0.09, 0.44), p = 0.2 |

| Written control (n = 145) | 3.03 (1.52) | 2.98 (1.30) | Reference | Reference |

| Baseline Intake | Follow-Up Intake | Complete Case Analysis a | Multiple Imputation Analysis b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean Difference vs. Control (95% CI), p-Value | Mean Difference vs. Control (95% CI), p-Value | |

| Randomized participants | ||||

| Telephone intervention (n = 73) | 1.71 (0.98) | 1.89 (0.88) | 0.08 (−0.25, 0.42), p = 0.62 | −0.05 (−0.38, 0.27), p = 0.75 |

| Online intervention (n = 86) | 1.85 (0.98) | 1.70 (1.12) | −0.16 (−0.46, 0.15), p = 0.32 | −0.02 (−0.37, 0.34), p = 0.92 |

| Written control (n = 81) | 1.68 (1.00) | 1.73 (0.92) | Reference | Reference |

| Preference participants | ||||

| Telephone intervention (n = 22) | 1.76 (1.09) | 1.78 (1.00) | 0.06 (−0.42, 0.54), p = 0.79 | −0.05 (−0.64, 0.55), p = 0.88 |

| Online intervention (n = 132) | 1.86 (0.97) | 1.91 (0.99) | 0.15 (−0.18, 0.48), p = 0.37 | −0.07 (−0.49, 0.34), p = 0.72 |

| Written control (n = 64) | 1.68 (0.82) | 1.64 (0.97) | Reference | Reference |

| All participants | ||||

| Telephone intervention (n = 95) | 1.72 (1.00) | 1.86 (0.91) | 0.09 (−0.18, 0.36), p = 0.51 | −0.05 (−0.31, 0.21), p = 0.68 |

| Online intervention (n = 218) | 1.85 (0.97) | 1.82 (1.05) | 0.00 (−0.22, 0.22), p = 1.00 | −0.05 (−0.28, 0.18), p = 0.67 |

| Written control (n = 145) | 1.68 (0.92) | 1.69 (0.94) | Reference | Reference |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wyse, R.J.; Jackson, J.K.; Hammersley, M.L.; Stacey, F.; Jones, R.A.; Okely, A.; Green, A.; Yoong, S.L.; Lecathelinais, C.; Innes-Hughes, C.; et al. Parent Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Outcomes from the Translational ‘Time for Healthy Habits’ Trial: Secondary Outcomes from a Partially Randomized Preference Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106165

Wyse RJ, Jackson JK, Hammersley ML, Stacey F, Jones RA, Okely A, Green A, Yoong SL, Lecathelinais C, Innes-Hughes C, et al. Parent Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Outcomes from the Translational ‘Time for Healthy Habits’ Trial: Secondary Outcomes from a Partially Randomized Preference Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):6165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106165

Chicago/Turabian StyleWyse, Rebecca J., Jacklyn K. Jackson, Megan L. Hammersley, Fiona Stacey, Rachel A. Jones, Anthony Okely, Amanda Green, Sze Lin Yoong, Christophe Lecathelinais, Christine Innes-Hughes, and et al. 2022. "Parent Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Outcomes from the Translational ‘Time for Healthy Habits’ Trial: Secondary Outcomes from a Partially Randomized Preference Trial" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106165

APA StyleWyse, R. J., Jackson, J. K., Hammersley, M. L., Stacey, F., Jones, R. A., Okely, A., Green, A., Yoong, S. L., Lecathelinais, C., Innes-Hughes, C., Xu, J., Gillham, K., & Rissel, C. (2022). Parent Fruit and Vegetable Consumption Outcomes from the Translational ‘Time for Healthy Habits’ Trial: Secondary Outcomes from a Partially Randomized Preference Trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6165. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106165

_Okely.png)