Planning for a Healthy Aging Program to Reduce Sedentary Behavior: Perceptions among Diverse Older Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Participants and Sample Selection

2.3. Instrumentation and Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Health Status and Patterns of Daily Activity

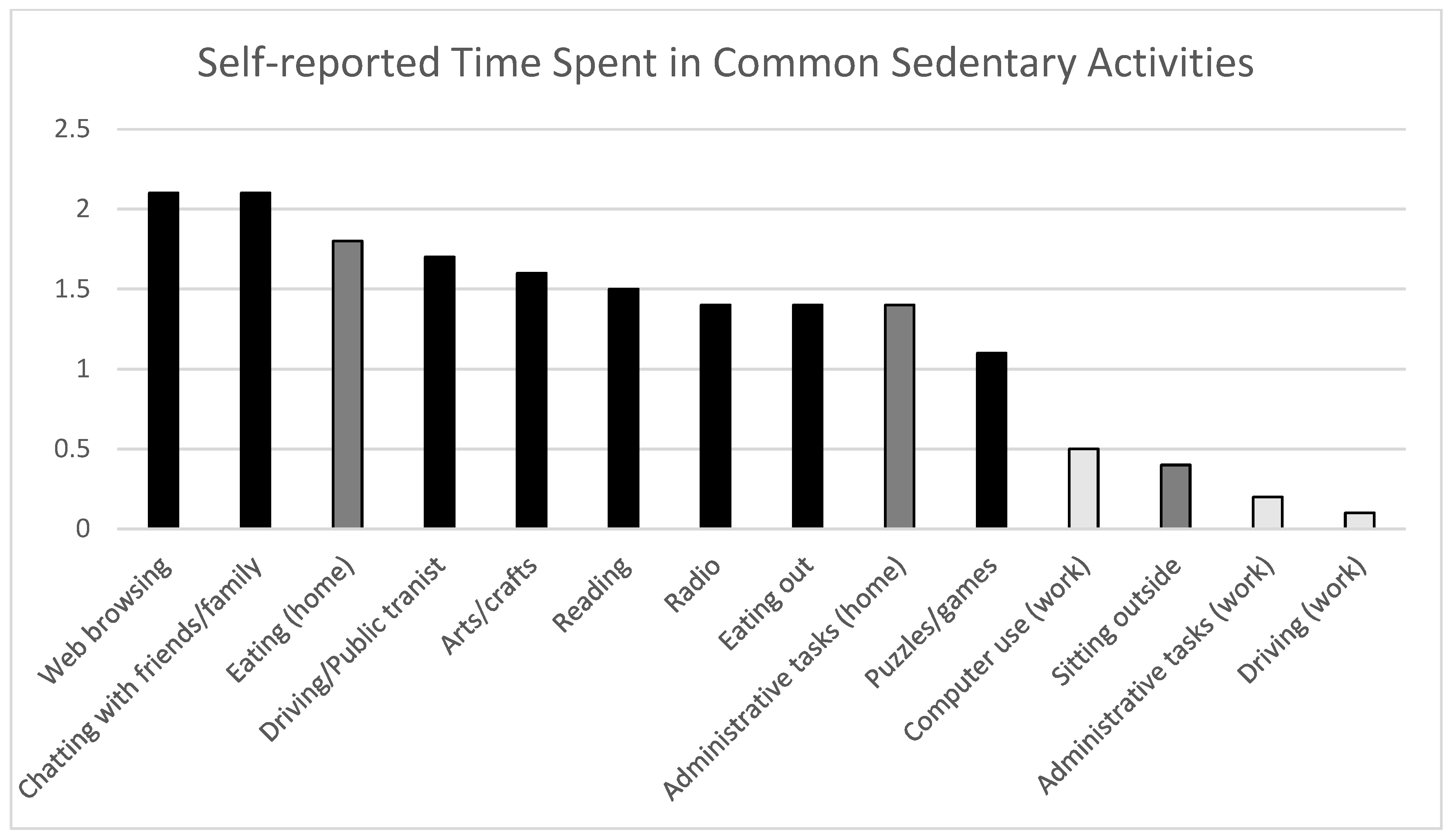

3.3. Older Adult Sedentary Behavior

3.4. Focus Groups Results

3.4.1. Theme 1. Avoiding Sedentary Behavior, Enjoying Seated Activities

3.4.2. Theme 2. Multi-Level Influences on Sedentary Behavior

Personal and Developmental Factors

Interpersonal Factors

Neighborhood and Societal Factors

3.4.3. Theme 3: Determining Own Path to Healthy Aging

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, K.B. Physical Inactivity among Adults Aged 50 Years and Older—United States, 2014. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 2016, 65, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keadle, S.K.; McKinnon, R.; Graubard, B.I.; Troiano, R.P. Prevalence and Trends in Physical Activity among Older Adults in the United States: A Comparison across Three National Surveys. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Harvey, J.A.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Skelton, D.A. How Sedentary Are Older People? A Systematic Review of the Amount of Sedentary Behavior. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, K.M.; Howard, V.J.; Hutto, B.; Colabianchi, N.; Vena, J.E.; Blair, S.N.; Hooker, S.P. Patterns of Sedentary Behavior in Us Middle-Age and Older Adults: The Regards Study. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matthews, C.E.; Chen, K.Y.; Freedson, P.S.; Buchowski, M.S.; Beech, B.M.; Pate, R.R.; Troiano, R.P. Amount of Time Spent in Sedentary Behaviors in the United States, 2003–2004. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008, 167, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dogra, S.; Stathokostas, L. Sedentary Behavior and Physical Activity Are Independent Predictors of Successful Aging in Middle-Aged and Older Adults. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012, e190654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenberg, D.E.; Bellettiere, J.; Gardiner, P.A.; Villarreal, V.N.; Crist, K.; Kerr, J. Independent Associations Between Sedentary Behaviors and Mental, Cognitive, Physical, and Functional Health Among Older Adults in Retirement Communities. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2016, 71, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Rezende, L.F.M.; Rey-López, J.P.; Matsudo, V.K.R.; Luiz, O.; Do, C. Sedentary Behavior and Health Outcomes among Older Adults: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmid, D.; Ricci, C.; Leitzmann, M.F. Associations of Objectively Assessed Physical Activity and Sedentary Time with All-Cause Mortality in US Adults: The NHANES Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rillamas-Sun, E.; LaMonte, M.J.; Evenson, K.R.; Thomson, C.A.; Beresford, S.A.; Coday, M.C.; Manini, T.M.; Li, W.; LaCroix, A.Z. The Influence of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior on Living to Age 85 Years Without Disease and Disability in Older Women. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2018, 73, 1525–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Oh, P.I.; Faulkner, G.E.; Bajaj, R.R.; Silver, M.A.; Mitchell, M.S.; Alter, D.A. Sedentary Time and Its Association With Risk for Disease Incidence, Mortality, and Hospitalization in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 162, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, W.C.; Rix, K.; Gibson, A.; Paxton, R.J. Sedentary Behavior and Health Outcomes in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. AIMS Med. Sci. 2020, 7, 10–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibaud, M.; Bloch, F.; Tournoux-Facon, C.; Brèque, C.; Rigaud, A.S.; Dugué, B.; Kemoun, G. Impact of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour on Fall Risks in Older People: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Eur Rev. Aging Phys. Act. 2012, 9, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, J.; Lindquist, L.A.; Chang, R.W.; Semanik, P.A.; Ehrlich-Jones, L.S.; Lee, J.; Sohn, M.-W.; Dunlop, D.D. Sedentary Behavior as a Risk Factor for Physical Frailty Independent of Moderate Activity: Results From the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlop, D.D.; Song, J.; Arntson, E.K.; Semanik, P.A.; Lee, J.; Chang, R.W.; Hootman, J.M. Sedentary Time in US Older Adults Associated With Disability in Activities of Daily Living Independent of Physical Activity. J. Phys. Act. Health 2015, 12, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gennuso, K.P.; Thraen-Borowski, K.M.; Gangnon, R.E.; Colbert, L.H. Patterns of Sedentary Behavior and Physical Function in Older Adults. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2016, 28, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, N.; Sugiyama, T.; Eakin, E.E.; Gardiner, P.A.; Tremblay, M.S.; Sallis, J.F. Adults’ Sedentary Behavior. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam-Seto, L.; Weir, P.; Dogra, S. Factors Influencing Sedentary Behaviour in Older Adults: An Ecological Approach. AIMS Public Health 2016, 3, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastin, S.; Fitzpatrick, N.; Andrews, M.; DiCroce, N. Determinants of Sedentary Behavior, Motivation, Barriers and Strategies to Reduce Sitting Time in Older Women: A Qualitative Investigation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 773–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greenwood-Hickman, M.A.; Renz, A.; Rosenberg, D.E. Motivators and Barriers to Reducing Sedentary Behavior Among Overweight and Obese Older Adults. Gerontologist 2016, 56, 660–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leask, C.F.; Sandlund, M.; Skelton, D.A.; Tulle, E.; Chastin, S.F. Modifying Older Adults’ Daily Sedentary Behaviour Using an Asset-Based Solution: Views from Older Adults. AIMS Public Health 2016, 3, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcewan, T.; Tam-Seto, L.; Dogra, S. Perceptions of Sedentary Behavior Among Socially Engaged Older Adults. Gerontologist 2016, 57, gnv689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- McGowan, L.J.; Powell, R.; French, D.P. How Acceptable Is Reducing Sedentary Behavior to Older Adults? Perceptions and Experiences Across Diverse Socioeconomic Areas. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 642–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, V.J.; Gray, C.M.; Fitzsimons, C.F.; Mutrie, N.; Wyke, S.; Deary, I.J.; Der, G.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Skelton, D.A.; Seniors USP Team; et al. What Do Older People Do When Sitting and Why? Implications for Decreasing Sedentary Behavior. Gerontologist 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Warren, T.Y.; Wilcox, S.; St. George, S.M.; Brandt, H.M. African American Women’s Perceived Influences on and Strategies to Reduce Sedentary Behavior. Qual Health Res. 2018, 28, 1112–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Bannay, H.; Jarus, T.; Jongbloed, L.; Yazigi, M.; Dean, E. Culture as a variable in health research: Perspectives and caveats. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 29, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider-Kamp, A. Health capital: Toward a conceptual framework for understanding the construction of individual health. Soc. Theory Health 2021, 19, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto Mas, F.; Allensworth, D.D.; Jones, C.P.; Jacobson, H.E. Advancing Equity and Eliminating Health Disparties. In Health Promotion Programs: From Theory to Practice, The Society for Public Health Education, 2nd ed.; Fertman, C.I., Allensworth, D.D., Eds.; Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fertman, C.I.; Allensworth, D.D.; Auld, M.E. What are Health Promotion Programs? In Health Promotion Programs: From Theory to Practice, 2nd ed.; Fertman, C.I., Allensworth, D.D., Eds.; The Society for Public Health Education; Jossey-Bass & Pfeiffer Imprints, Wiley: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. (Eds.) Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Law, M.; Cooper, B.; Strong, S.; Stewart, D.; Rigby, P.; Letts, L. The Person-Environment-Occupation Model: A Transactive Approach to Occupational Performance. Can. J. Occup. 1996, 63, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen-Kyle, L. A Concept Analysis of Healthy Aging. Nurs. Forum 2005, 40, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.M.; Mulhausen, P.; Cleveland, M.L.; Coll, P.P.; Daniel, K.M.; Hayward, A.D.; Shah, K.; Skudlarska, B.; White, H.K. Healthy Aging: American Geriatrics Society White Paper Executive Summary: AGS White Paper on Healthy Aging. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2019, 67, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization. World Report on Ageing and Health: Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva: Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Northridge, M.E.; Shedlin, M.; Schrimshaw, E.W.; Estrada, I.; De La Cruz, L.; Peralta, R.; Birdsall, S.; Metcalf, S.S.; Chakraborty, B.; Kunzel, C. Recruitment of Racial/Ethnic Minority Older Adults through Community Sites for Focus Group Discussions. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldana, J. Fundamentals of Qualitative Data Analysis. In Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M., Saldana, J., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D.M. Research and Evaluation in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity with Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed Methods, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Aubert, S.; Barnes, J.D.; Saunders, T.J.; Carson, V.; Latimer-Cheung, A.E.; Chastin, S.F.M.; Altenburg, T.M.; Chinapaw, M.J.M.; On behalf of SBRN Terminology Consensus Project Participants. Sedentary Behavior Research Network (SBRN)—Terminology Consensus Project Process and Outcome. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guest, G.; Namey, E.; McKenna, K. How Many Focus Groups Are Enough? Building an Evidence Base for Nonprobability Sample Sizes. Field Methods 2017, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, P.A.; Clark, B.K.; Healy, G.N.; Eakin, E.G.; Winkler, E.A.H.; Owen, N. Measuring Older Adults’ Sedentary Time: Reliability, Validity, and Responsiveness. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rosenberg, D.E.; Norman, G.J.; Wagner, N.; Patrick, K.; Calfas, K.J.; Sallis, J.F. Reliability and Validity of the Sedentary Behavior Questionnaire (SBQ) for Adults. J. Phys. Act. Health 2010, 7, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- On behalf of the Seniors USP Team; Chastin, S.F.M.; Dontje, M.L.; Skelton, D.A.; Čukić, I.; Shaw, R.J.; Gill, J.M.R.; Greig, C.A.; Gale, C.R.; Deary, I.J.; et al. Systematic Comparative Validation of Self-Report Measures of Sedentary Time against an Objective Measure of Postural Sitting (ActivPAL). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the Framework Method for the Analysis of Qualitative Data in Multi-Disciplinary Health Research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Compernolle, S.; De Cocker, K.; Cardon, G.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Van Dyck, D. Older Adults’ Perceptions of Sedentary Behavior: A Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Gerontologist 2020, 60, e572–e582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, G.H.; Williams, R.K.; Clarke, D.J.; English, C.; Fitzsimons, C.; Holloway, I.; Lawton, R.; Mead, G.; Patel, A.; Forster, A. Exploring Adults’ Experiences of Sedentary Behaviour and Participation in Non-Workplace Interventions Designed to Reduce Sedentary Behaviour: A Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Neill, C.; Dogra, S. Different Types of Sedentary Activities and Their Association With Perceived Health and Wellness Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. Am. J. Health Promot. 2016, 30, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, D.; Chase, J.-A.D. The Social Context of Sedentary Behaviors and Their Relationships With Health in Later Life. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2019, 27, 797–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottenvall Hammar, I.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Wilhelmson, K.; Eklund, K. Self-Determination among Community-Dwelling Older Persons: Explanatory Factors. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2016, 23, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aday, R.H.; Wallace, B.; Krabill, J.J. Linkages Between the Senior Center as a Public Place and Successful Aging. Act. Adapt. Aging 2019, 43, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, R. The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community; Marlowe; Publishers Group West: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.; Currie, C.L.; Copeland, J.L. Sedentary Behavior among Adults: The Role of Community Belonging. Prev. Med. Rep. 2016, 4, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Total | Senior Center A | Senior Center B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 46) | (n = 22) | (n = 24) | |

| Age, years | 75.6 [7.8] | 74.8 [9.3] | 76.3 [6.4] |

| Gender, female | 41 (89.1%) | 21 (95.5%) | 20 (83.3%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Black, or of Caribbean or African descent | 27 (60.0%) | 20 (95.2%) | 7 (29.2%) |

| White, or of European descent | 11 (24.4%) | - | 11 (45.8%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2 (4.4%) | - | 2 (4.4%) |

| Other | 5 (11.1%) | 1 (4.8%) | 4 (16.7%) |

| Educational attainment | |||

| College degree or higher | 22 (48.9%) | 2 (9.5%) | 20 (83.3%) |

| Some College | 11 (24.4%) | 8 (38.1%) | 3 (12.5%) |

| High School Diploma/GED | 9 (20.0%) | 8 (38.1%) | 1 (4.2%) |

| Less than High School | 3 (6.7%) | 3 (14.3%) | - |

| Employment Status | |||

| Retired | 39 (89.7%) | 17 (77.3%) | 22 (95.7%) |

| Disabled | 4 (8.9%) | 3 (13.6%) | 1 (4.4%) |

| Employed | 2 (4.4%) | 2 (9.1%) | - |

| Relationship Status | |||

| Single, never married | 10 (22.7%) | 6 (30.0%) | 4 (16.7%) |

| Married/committed relationship | 5 (11.4%) | 1 (5.0%) | 4 (16.7%) |

| Widowed | 15 (34.1%) | 9 (45.0%) | 6 (25.0%) |

| Divorced | 11 (25.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 8 (33.3%) |

| Separated | 3 (6.8%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (8.3%) |

| Living Status | |||

| Lives alone | 28 (60.9%) | 15 (68.2%) | 13 (54.2%) |

| Lives with spouse/partner | 5 (10.9%) | 1 (4.5%) | 4 (16.7%) |

| Lives with other family members | 8 (17.4%) | 6 (27.3%) | 2 (8.3%) |

| Other | 5 (10.4%) | - | 5 (20.8%) |

| How often do you visit the center? | |||

| Daily | 17 (37.0%) | 12 (54.5%) | 5 (20.8%) |

| A few times a week | 21 (45.6%) | 8 (36.4%) | 13 (54.2%) |

| Once a week | 6 (13.0%) | - | 6 (25.0%) |

| A few times a month | 2 (4.4%) | 2 (9.1%) | - |

| How do you usually get to the center? | |||

| Walk or bike | 30 (65.2%) | 21 (95.5%) | 9 (37.5%) |

| Public transit | 10 (21.5%) | - | 10 (41.7%) |

| Para-transit | 4 (8.7%) | 1 (4.6%) | 3 (12.5%) |

| Private Car | 2 (4.4%) | - | 2 (8.3%) |

| Total (n = 46) | |

|---|---|

| General physical health is? | |

| Excellent | 5 (10.87%) |

| Very good | 16 (34.8%) |

| Good | 20 (43.5%) |

| Fair/Poor | 5 (10.9%) |

| General mental health is? | |

| Excellent | 10 (21.7%) |

| Very Good | 17 (36.97%) |

| Good | 13 (28.3%) |

| Fair/Poor | 6 (13.0%) |

| Compared to my peers, I am... | |

| More physically active | 31 (68.9%) |

| About the same | 10 (22.2%) |

| Less physically active | 4 (8.9%) |

| Self-reported intensity and frequency of physical activities | |

| Over the past 30 days, … | |

| …did you walk or bike to do you errands? | |

| Yes | 38 (82.6%) |

| No or unable | 8 (17.4%) |

| …did you do any vigorous recreational activities for at least 10 min? | (n = 45) |

| Yes | 24 (53.3%) |

| No or unable | 19 (42.2%) |

| I don’t know | 2 (4.4%) |

| If yes, how often? | (n = 24) |

| Once a week | 4 (16.7%) |

| Most days a week | 18 (75.0%) |

| Every day | 1 (4.2%) |

| I don’t know | 1 (4.2%) |

| …did you do any moderate-intensity recreational activities for at least 10 min? | (n = 44) |

| Yes | 33 (75.0%) |

| No or unable | 9 (20.5%) |

| I don’t know/unable | 2 (4.5%) |

| If yes, how often? | (n = 33) |

| Once a week | 4 (12.1%) |

| Most days a week | 20 (60.6%) |

| Every day | 7 (21.2%) |

| I don’t know | 2 (6.1%) |

| …did you do any heavy work in the house or yard for at least 10 min? | (n = 44) |

| Yes | 23 (52.3%) |

| No | 18 (40.9%) |

| I don’t know | 3 (6.8%) |

| If yes, how often? | (n = 23) |

| Once a week | 5 (21.7%) |

| Most days a week | 13 (56.5%) |

| Every day | 2 (8.7%) |

| I don’t know | 3 (13.0%) |

| Mean (SD) self-reported total sitting time | |

| In the past week, I typically sat for ____ hours a day | 4.5 [2.0] |

| Theme 1: Avoiding Sedentary Behavior, Enjoying Seated Activities | |

|---|---|

| Costs of sedentary behavior |

|

| Benefits of sedentary behavior |

|

| Theme 2. Multi-level Influences on Sedentary Behavior | |

| Personal and developmental factors |

|

| Interpersonal factors |

|

| Neighborhood and societal factors |

|

| Theme 3.Determining Own Path to Healthy Aging | |

| Attitudes towards aging |

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nuwere, E.; Barone Gibbs, B.; Toto, P.E.; Taverno Ross, S.E. Planning for a Healthy Aging Program to Reduce Sedentary Behavior: Perceptions among Diverse Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106068

Nuwere E, Barone Gibbs B, Toto PE, Taverno Ross SE. Planning for a Healthy Aging Program to Reduce Sedentary Behavior: Perceptions among Diverse Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):6068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106068

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuwere, Efekona, Bethany Barone Gibbs, Pamela E. Toto, and Sharon E. Taverno Ross. 2022. "Planning for a Healthy Aging Program to Reduce Sedentary Behavior: Perceptions among Diverse Older Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 6068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106068

APA StyleNuwere, E., Barone Gibbs, B., Toto, P. E., & Taverno Ross, S. E. (2022). Planning for a Healthy Aging Program to Reduce Sedentary Behavior: Perceptions among Diverse Older Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6068. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19106068