Suicide Trends in the Italian State Police during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Comparison with the Pre-Pandemic Period

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/131056 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Bachmann, S. Epidemiology of Suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sokolowski, M.; Wasserman, D. Genetic origins of suicidality? A synopsis of genes in suicidal behaviours, with regard to evidence diversity, disorder specificity and neurodevelopmental brain transcriptomics. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 37, 1–11, Erratum in Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 41, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, R.I.; Hales, R.E. Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management, 2nd ed.; Arlington, V.A., Ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, C.K.; Hirschfeld, R.M. Psychosocial factors and suicidal behavior. Life events, early loss, and personality. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1986, 487, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldessarini, R.J. Epidemiology of suicide: Recent developments. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 29, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Moitra, M.; Santomauro, D.; Degenhardt, L.; Collins, P.Y.; Whiteford, H.; Vos, T.; Ferrari, A. Estimating the risk of suicide associated with mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021, 137, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racine, M. Chronic pain and suicide risk: A comprehensive review. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 87 Pt B, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, K.E.; Brock, R.; Charnock, J.; Wickramasinghe, B.; Will, O.; Pitman, A. Risk of Suicide After Cancer Diagnosis in England. JAMA Psychiatry 2019, 76, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, S.; Peng, P.; Ma, F.; Tang, F. Prediction of risk of suicide death among lung cancer patients after the cancer diagnosis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 292, 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguiano, L.; Mayer, D.K.; Piven, M.L.; Rosenstein, D. A Literature Review of Suicide in Cancer Patients. Cancer Nurs. 2012, 35, E14–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kposowa, A.J. Divorce and suicide risk. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2003, 57, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mortensen, P.B.; Agerbo, E.; Erikson, T.; Qin, P.; Westergaard-Nielsen, N. Psychiatric illness and risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Lancet 2000, 355, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kposowa, A.J. Unemployment and suicide: A cohort analysis of social factors predicting suicide in the US National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Psychol. Med. 2001, 31, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calati, R.; Ferrari, C.; Brittner, M.; Oasi, O.; Olié, E.; Carvalho, A.F.; Courtet, P. Suicidal thoughts and behaviors and social isolation: A narrative review of the literature. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 245, 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M. Epidemiology of suicide: From population to single cases. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2019, 29, e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stone, D.M.; Simon, T.R.; Fowler, K.A.; Kegler, S.R.; Yuan, K.; Holland, K.M.; Ivey-Stephenson, A.Z.; Crosby, A.E. Vital Signs: Trends in State Suicide Rates—United States, 1999-2016 and Circumstances Contributing to Suicide—27 States, 2015. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 617–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ISTAT (2017) Malattie Fisiche e Mentali Associate al Suicidio: Un’analisi Sulle Cause Multiple di Morte. Nota Informativa, 15 February 2017—Retrieved Oct 30, 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/196880 (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Kõlves, K.; McDonough, M.; Crompton, D.; de Leo, D. Choice of a suicide method: Trends and characteristics. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 260, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houtsma, C.; Butterworth, S.E.; Anestis, M.D. Firearm suicide: Pathways to risk and methods of prevention. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 22, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarai, S.K.; Abaid, B.; Lippmann, S. Guns and Suicide: Are They Related? Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2017, 19, 17br02116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, C.; Del Casale, A.; Cucè, P.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Pelliccione, A.; Marconi, W.; Saccente, F.; Messina, R.; Santorsa, R.; Rapinesi, C.; et al. Suicide among Italian police officers from 1995 to 2017. Riv. Psichiatr. 2019, 54, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, S.; Fornaro, M.; Messina, R.; Pompili, M.; Ciprani, F. Suicide mortality data from the Italian police during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2021, 20, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Passos, F.; Queiros, C. Suicides of Male Portuguese Police Officers—10 years of National Data. Crisis 2019, 40, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nota, P.M.; Anderson, G.S.; Ricciardelli, R.; Carleton, R.N.; Groll, D. Mental disorders, suicidal ideation, plans and attempts among Canadian police. Occup. Med. 2020, 70, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Encrenaz, G.; Miras, A.; Contrand, B.; Séguin, M.; Moulki, M.; Queinec, R.; René, J.S.; Fériot, A.; Mougin, M.; Bonfils, M.; et al. Suicide dans la Police nationale française: Trajectoires de vie et facteurs associés [Suicide among the French National Police forces: Implication of life events and life trajectories]. Encephale 2016, 42, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jetelina, K.K.; Molsberry, R.J.; Gonzalez, J.R.; Beauchamp, A.M.; Hall, T. Prevalence of Mental Illness and Mental Health Care Use Among Police Officers. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e2019658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, H. Suicidality among Police. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2008, 21, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.M.B.; Hem, E.; Lau, B.; Loeb, M.; Ekeberg, Ø. Suicidal Ideation and Attempts in Norwegian Police. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2003, 33, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, C.; Del Casale, A.; Ferracuti, S.; Cucè, P.; Santorsa, R.; Pelliccione, A.; Marotta, G.; Tavella, G.; Tatarelli, R.; Girardi, P.; et al. How do recruits and superintendents perceive the problem of suicide in the Italian State Police? Ann. Ist. Super Sanita 2018, 54, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, L.; Heidinger, T. Hitting Close to Home: The Effect of COVID-19 Illness in the Social Environment on Psychological Burden in Older Adults. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 737787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jefsen, O.H.; Rohde, C.; Nørremark, B.; Østergaard, S.D. COVID-19-related self-harm and suicidality among individuals with mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2020, 142, 152–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, L. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM 2020, 113, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19 (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Nochaiwong, S.; Ruengorn, C.; Thavorn, K.; Hutton, B.; Awiphan, R.; Phosuya, C.; Ruanta, Y.; Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T. Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, F.; Hajure, M. Magnitude and determinants of the psychological impact of COVID-19 among health care workers: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2021, 9, 20503121211012512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabarkapa, S.; Nadjidai, S.E.; Murgier, J.; Ng, C.H. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: A rapid systematic review. Brain Behav. Immun. Health 2020, 8, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, B.; Al-Jumaily, A.; Fong, K.N.K.; Prasad, P.; Meena, S.K.; Tong, R.K. Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak Quarantine, Isolation, and Lockdown Policies on Mental Health and Suicide. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 565190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galán, J.; Lázaro-Pérez, C.; Martínez-López, J.Á.; Fernández-Martínez, M.D.M. Burnout in Spanish Security Forces during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenkel, M.O.; Giessing, L.; Egger-Lampl, S.; Hutter, V.; Oudejans, R.; Kleygrewe, L.; Jaspaert, E.; Plessner, H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on European police officers: Stress, demands, and coping resources. J. Crim. Justice 2021, 72, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Bodla, A.A.; Chen, C. An Exploratory Study of Police Officers’ Perceptions of Health Risk, Work Stress, and Psychological Distress During the COVID-19 Outbreak in China. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 632970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogner, J.; Miller, B.L.; McLean, K. Police Stress, Mental Health, and Resiliency during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 1–13, 718–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, S.; Merchant, R.M.; Lurie, N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020, 180, 817–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Magnavita, N.; Chirico, F.; Garbarino, S.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Santacroce, E.; Zaffina, S. SARS/MERS/SARS-CoV-2 Outbreaks and Burnout Syndrome among Healthcare Workers. An Umbrella Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Niu, Z.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Lei, L.; Homish, G.G.; Cao, Y.; Zorich, S.C.; Yue, Y.; Liu, R.; et al. COVID-19 Related Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and PTSD among US Adults. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 301, 113959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, P.; Bonanni, L.; Kotzalidis, G.D.; Fiaschè, F.; Del Casale, A. Evolution of International Psychiatry. Psychiatry Int. 2020, 1, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, D.; Appleby, L.; Arensman, E.; Hawton, K.; John, A.; Kapur, N.; Khan, M.; O’Connor, R.C.; Pirkis, J.; COVID-19 Suicide Prevention Research Collaboration. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 468–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M. Can we expect a rise in suicide rates after the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021, 52, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K.; Malmberg, A.; Simkin, S. Suicide in doctors. A psychological autopsy study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2004, 57, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Balch, C.M.; Dyrbye, L.; Bechamps, G.; Russell, T.; Satele, D.; Rummans, T.; Swartz, K.; Novotny, P.J.; Sloan, J.; et al. Special report: Suicidal ideation among American surgeons. Arch. Surg. 2011, 146, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventriglio, A.; Watson, C.; Bhugra, D. Suicide among doctors: A narrative review. Indian J. Psychiatry 2020, 62, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby, L. What has been the effect of covid-19 on suicide rates? BMJ 2021, 372, n834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; John, A.; Shin, S.; DelPozo-Banos, M.; Arya, V.; Analuisa-Aguilar, P.; Appleby, L.; Arensman, E.; Bantjes, J.; Baran, A.; et al. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: An interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, 579–588, Erratum in: Lancet Psychiatry 2021, 8, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travis-Lumer, Y.; Kodesh, A.; Goldberg, Y.; Frangou, S.; Levine, S.Z. Attempted suicide rates before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Interrupted time series analysis of a nationally representative sample. Psychol. Med. 2021, 19, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pompili, M.; O’Connor, R.C.; Van Heeringen, K. Suicide Prevention in the European Region. Crisis 2020, 41 (Suppl. S1), S8–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihmer, Z.; Gonda, X.; Döme, P.; Serafini, G.; Pompili, M. Suicid risk in mood disorders—Can we better prevent suicide than predict it? Psychiatr. Hung. 2018, 33, 309–315. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, A.; Sarli, G.; Polidori, L.; Lester, D.; Pompili, M. The Role of New Technologies to Prevent Suicide in Adolescence: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Medicina 2021, 57, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokkenstorm, J.K.; Huisman, A.; Kerkhof, A.J. Suïcidepreventie via internet en telefoon: 113Online [Suicide prevention via the internet and the telephone: 113Online]. Tijdschr. Psychiatr. 2012, 54, 341–348. [Google Scholar]

- Moutier, C.; Norcross, W.; Jong, P.; Norman, M.; Kirby, B.; McGuire, T.; Zisook, S. The Suicide Prevention and Depression Awareness Program at the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pompili, M. Suicide at the Time of COVID-19. 2020. Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/09/10/maurizio-pompili-suicide-prevention-at-the-time-of-covid-19/ (accessed on 26 August 2021).

- Mari, E.; Fraschetti, A.; Lausi, G.; Pizzo, A.; Baldi, M.; Paoli, E.; Giannini, A.M.; Avallone, F. Forced Cohabitation during Coronavirus Lockdown in Italy: A Study on Coping, Stress and Emotions among Different Family Patterns. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, S.R.; Rhodes, J.E.; Scoglio, A.A. Changes in marital and partner relationships in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina: An analysis with low-income women. Psychol. Women Q. 2012, 36, 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lazarus, R.S. From Psychological Stress to the Emotions: A History of Changing Outlooks. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1993, 44, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Campbell, E.A. Sources of occupational stress in the police. Work Stress 1990, 4, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maran, D.A.; Varetto, A.; Zedda, M.; Ieraci, V. Occupational stress, anxiety and coping strategies in police officers. Occup. Med. 2015, 65, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Queirós, C.; Passos, F.; Bártolo, A.; Marques, A.J.; Da Silva, C.F.; Pereira, A. Burnout and Stress Measurement in Police Officers: Literature Review and a Study With the Operational Police Stress Questionnaire. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed, S.; Ashwick, R.; Schlosser, M.; Jones, R.; Rowe, S.; Billings, J. Global prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in police personnel: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 77, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordner, G.W. Police Administration, 8th ed.; Anderson Publishing: Waltham, MA, USA, 2013; 566p. [Google Scholar]

- Kop, N.; Euwema, M.; Schaufeli, W. Burnout, job stress and violent behaviour among Dutch police officers. Work Stress 1999, 13, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leino, T.M.; Selin, R.; Summala, H.; Virtanen, M. Violence and psychological distress among police officers and security guards. Occup. Med. 2011, 61, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leino, T.M. Work-Related Violence and Its Associations with Psychological Health: A Study of Finnish Police Patrol Officers and Security Guards; Research Report No.: 98; Finnish Institute of Occupational Health: Helsinki, Finland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Maran, D.A.; Zedda, M.; Varetto, A. Organizational and Occupational Stressors, Their Consequences and Coping Strategies: A Questionnaire Survey among Italian Patrol Police Officers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Setti, I.; Argentero, P. The influence of operational and organizational stressors on the well-being of municipal police officers. La Med. Del Lav. 2013, 104, 368–379. [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino, S.; Cuomo, G.; Chiorri, C.; Magnavita, N. Association of work-related stress with mental health problems in a special police force unit. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e002791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stanley, I.H.; Hom, M.A.; Joiner, T.E. A systematic review of suicidal thoughts and behaviors among police officers, firefighters, EMTs, and paramedics. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016, 44, 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Orden, K.A.; Witte, T.K.; Cukrowicz, K.C.; Braithwaite, S.R.; Selby, E.A.; Joiner, T.E., Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol. Rev. 2010, 117, 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cerel, J.; Jones, B.; Brown, M.; Weisenhorn, D.A.; Patel, K. Suicide Exposure in Law Enforcement Officers. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2019, 49, 1281–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, A.; Amerio, A.; Odone, A.; Baertschi, M.; Richard-Lepouriel, H.; Weber, K.; Di Marco, S.; Prelati, M.; Aguglia, A.; Escelsior, A.; et al. Suicide prevention from a public health perspective: What makes life meaningful? The opinion of some suicidal patients. Acta Biomed. 2020, 91, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

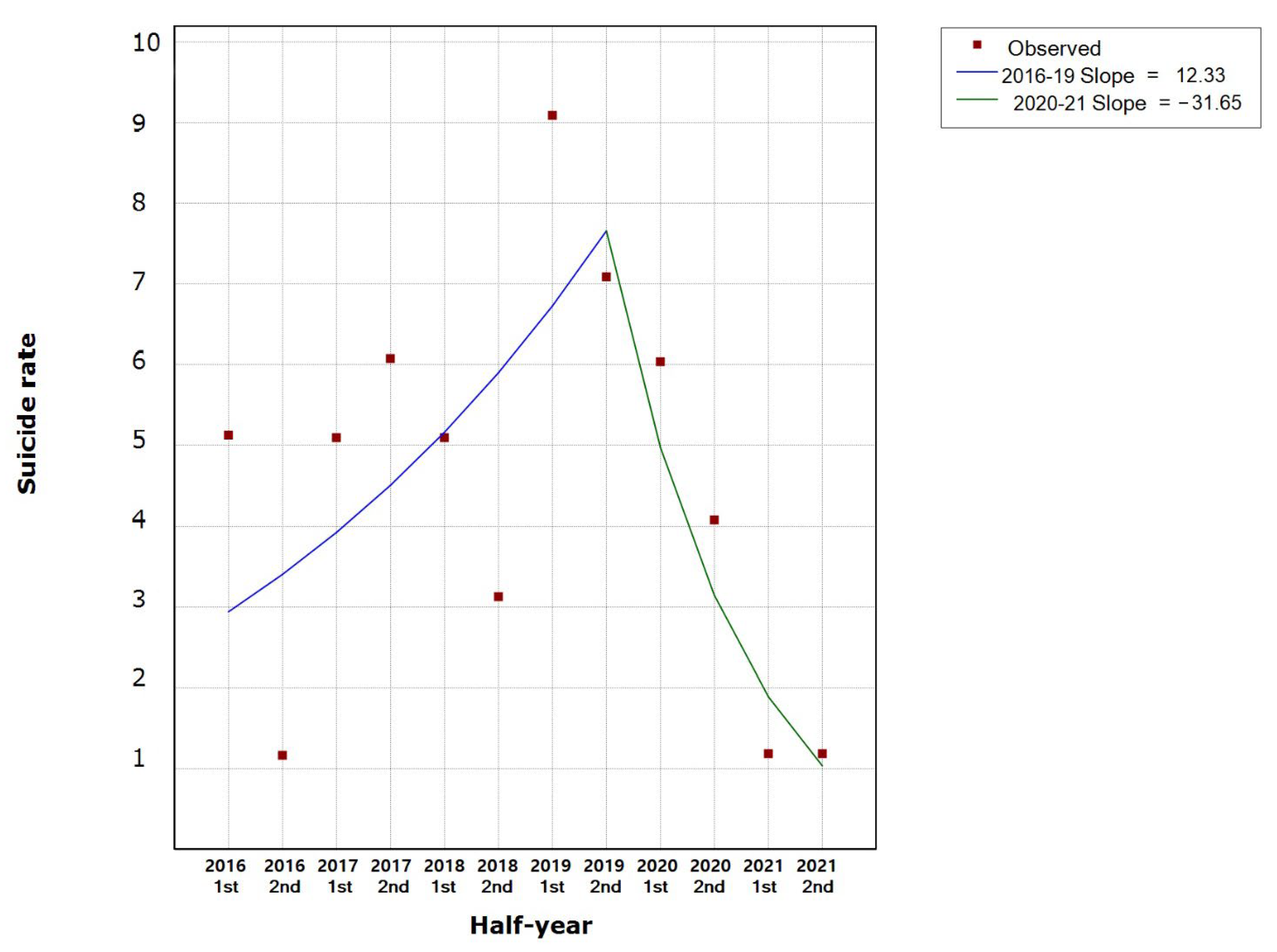

| Segment | Lower Endpoint | Upper Endpoint | HPC | Lower CI | Upper CI | Test Statistic (t) | Prob > |t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2021 | January 2016 | October 2021 | −3.9 % | −13.6 | 6.9 | −0.8 | 0.424 |

| 2016–2019 | January 2016 | December 2019 | 12.3 % | −7.9 | 37.0 | 1.4 | 0.209 |

| 2020–2021 | December 2019 | October 2021 | −31.6 % | −57.3 | 9.4 | −1.9 | 0.098 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maselli, S.; del Casale, A.; Paoli, E.; Pompili, M.; Garbarino, S. Suicide Trends in the Italian State Police during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Comparison with the Pre-Pandemic Period. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5904. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105904

Maselli S, del Casale A, Paoli E, Pompili M, Garbarino S. Suicide Trends in the Italian State Police during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Comparison with the Pre-Pandemic Period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(10):5904. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105904

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaselli, Silvana, Antonio del Casale, Elena Paoli, Maurizio Pompili, and Sergio Garbarino. 2022. "Suicide Trends in the Italian State Police during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Comparison with the Pre-Pandemic Period" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 10: 5904. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105904

APA StyleMaselli, S., del Casale, A., Paoli, E., Pompili, M., & Garbarino, S. (2022). Suicide Trends in the Italian State Police during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic: A Comparison with the Pre-Pandemic Period. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 5904. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105904