Liberalization and Governance in the Geographical Distribution of Pharmacies in Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

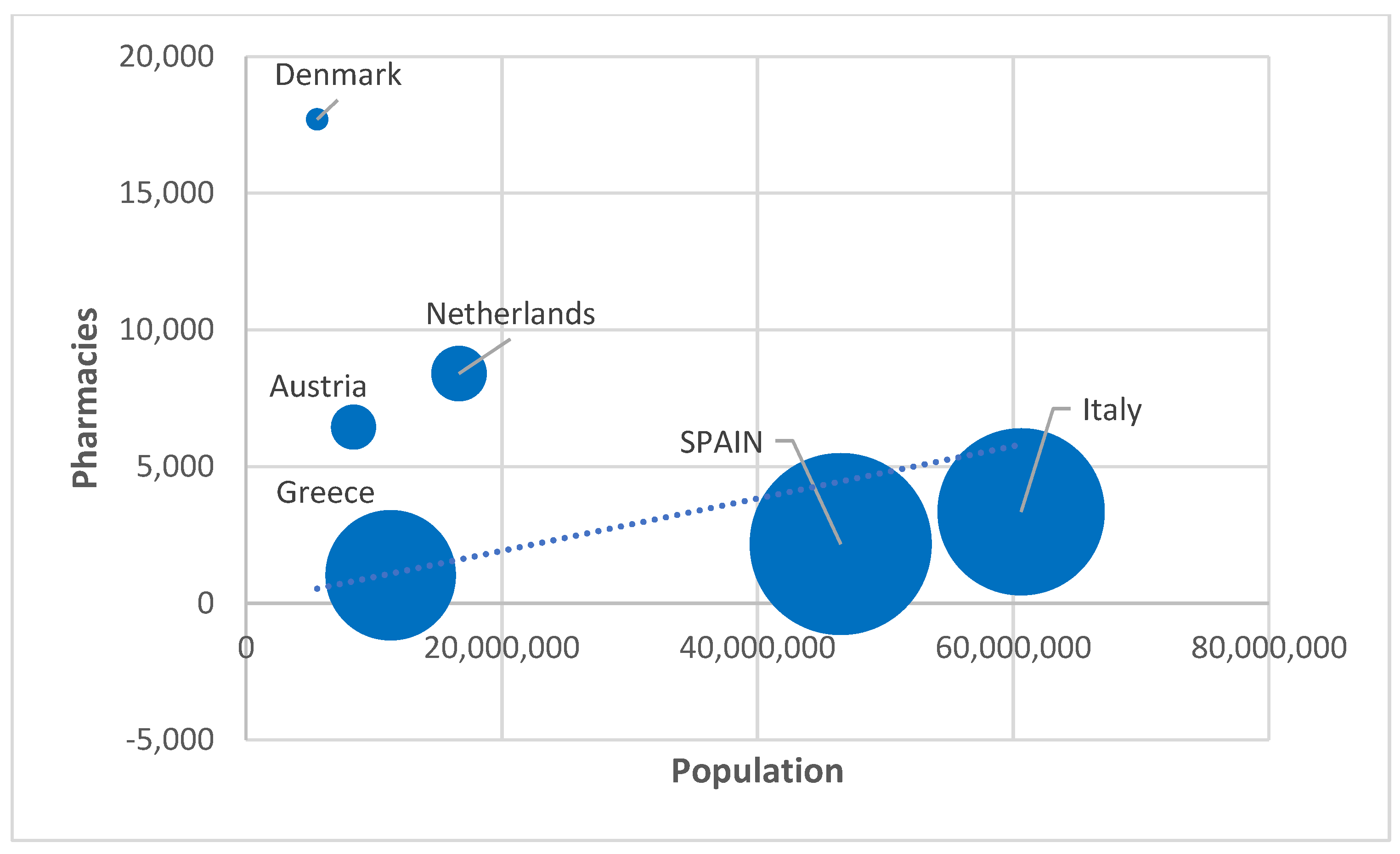

3.1. The Governance of Pharmacies in the European Union and Liberalisation Attempts in Spain

3.1.1. Pharmacy Models in the European Union

3.1.2. The Attempts to Liberalize Pharmacies in Spain

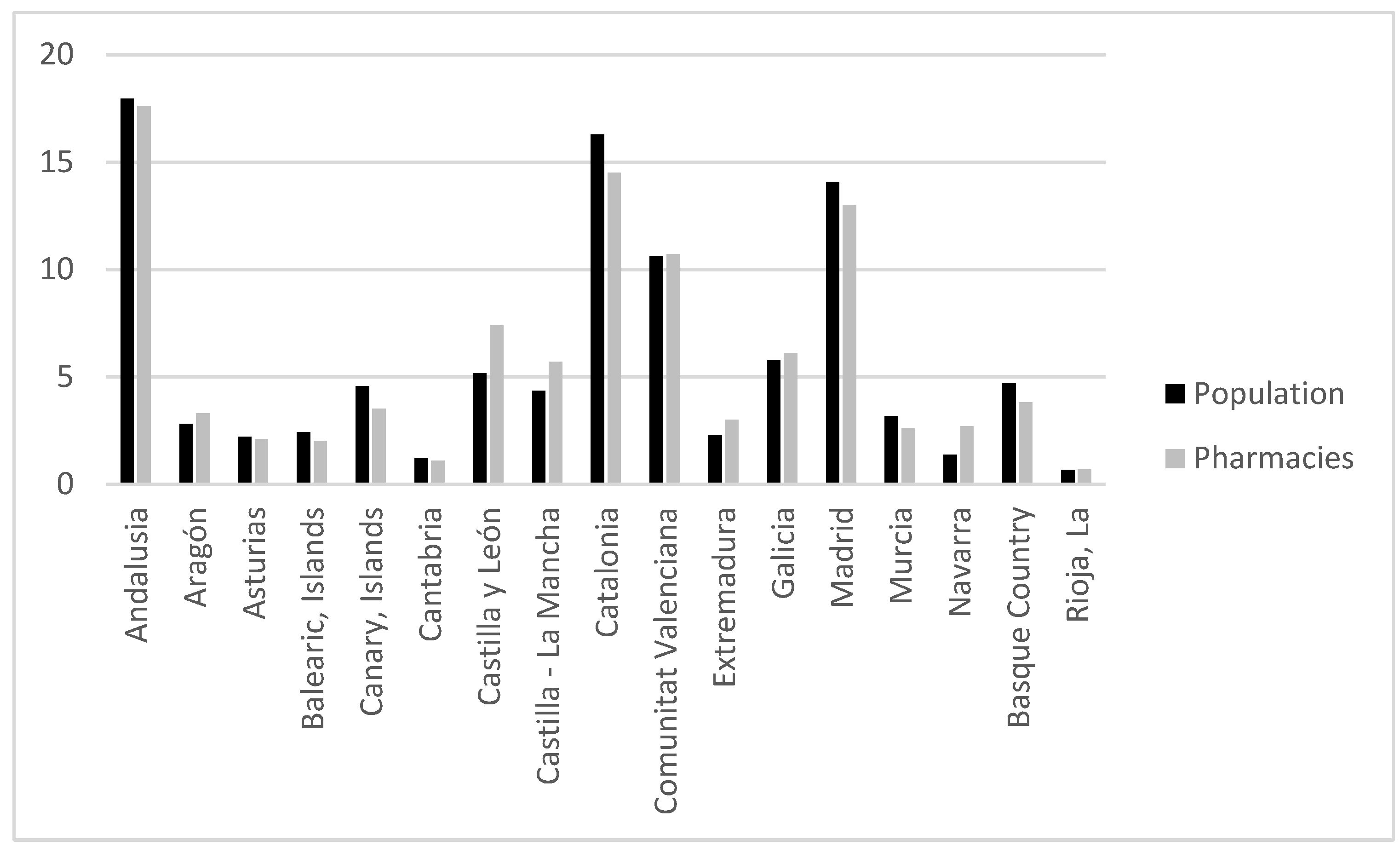

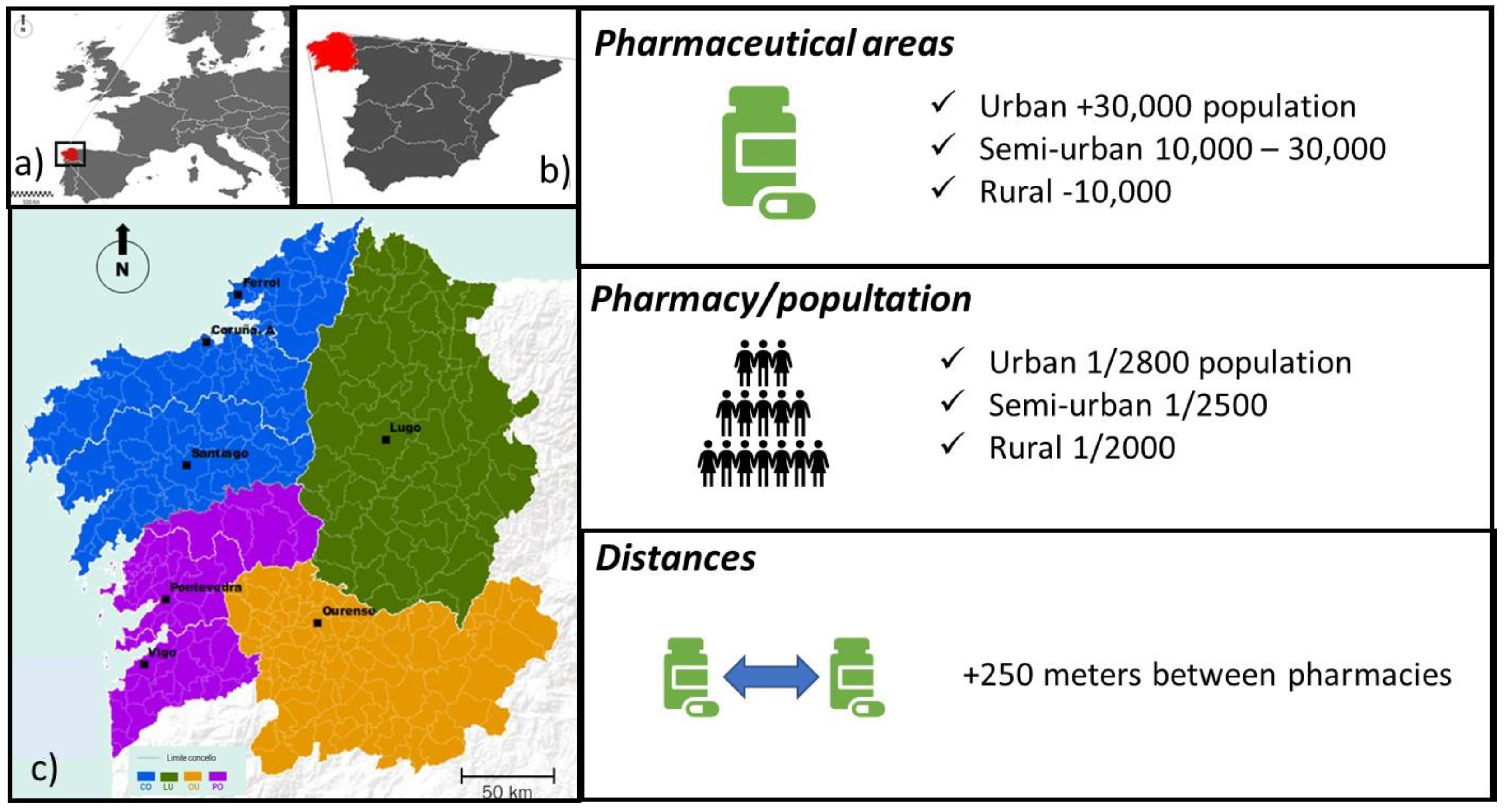

3.2. Presentation of Pharmaceutical Regulations and the Distribution of Pharmacies in Spain

- (1)

- In each pharmaceutical area, only one pharmacy can be created per module of 2800 inhabitants.

- (2)

- An additional pharmacy may only be opened if this proportion is exceeded, which will be created by the fraction greater than 2000 inhabitants.

- (3)

- Each pharmacy must respect a minimum distance from existing pharmacies, which, as a rule, will be a minimum of 250 m.

- (1)

- Urban pharmaceutical areas: These correspond to municipalities with more than 30,000 inhabitants.

- (2)

- Semi-urban pharmaceutical areas: These correspond to municipalities with a number of inhabitants between 10,000 and 30,000.

- (3)

- Rural pharmaceutical areas: These correspond to municipalities with less than 10,000 inhabitants.

- (1)

- Urban pharmaceutical areas: one pharmacy for every 2800 registered inhabitants. Following the criteria applied throughout Spain, unless that proportion is exceeded by 1500 inhabitants, in which case a new pharmacy may be established if there has been a net population increase in the last 5 years.

- (2)

- Semi-urban pharmaceutical areas: one pharmacy for every 2500 registered inhabitants, unless that proportion is exceeded by 1500 inhabitants, in which case a new pharmacy may be established as long as there has been a net population increase in the last 5 years.

- (3)

- Rural pharmaceutical areas: one for every 2000 registered inhabitants, unless that proportion is exceeded by 1500, in which case a new pharmacy may be established as long as there has been a net population increase in the last 5 years.

- (1)

- The opening of a pharmacy, either new or as a result of relocation, may not be done at a distance less than 250 m from other pharmacies or from a public health care center open to the public or where it will be built as planned. This is the same distance that was already applied at a Spanish level.

- (2)

- Exceptionally, in those pharmaceutical areas that have a single pharmacy, this minimum distance may not be required when there are reasons of general interest that justify it.

- (3)

- The procedure, conditions, and criteria for measuring these distances is regulated.

- (4)

- When a pharmacy is forced to temporarily move with an obligation to return, the minimum distance referred to in number 1 of this article is reduced to 125 m.

4. Discussion

- (1)

- In Spain, there is a very clear territorial imbalance within the pharmaceutical sector. Spanish legislation does not help at all to homogenize the pharmaceutical service, either at the Spanish level or internally within each of the 17 autonomous regions that have the most Health powers. It was proposed that, regardless of the existence of a basic legislation, which includes the criteria for planning pharmacies in Spain, it is necessary to legislate according to the characteristics of the territory to avoid provision imbalances such as those that exist today. Along the same lines, a Health pact is not necessary, but agreements for Health and the coordination in the provision of services and policies are. It is unreasonable to have 17 types of healthcare cards in Spain and some regions with a pharmacy for every 1000 inhabitants and in others one for every 4000 inhabitants. These are measures that could be implemented while the map of the pharmacies is readjusted according to the characteristics of the territory.

- (2)

- Regarding the issue of liberalization, we understand the position of the General Council of the Official Associations of Pharmacists of Spain, which argued that the deregulation of the sector does not improve the situation in terms of social welfare and would harm the patient. Pharmacists affirm that they have a regulatory model for pharmacies with a per capita rate much higher than in countries where the sector is liberalized. In addition, they state that, when it is liberalized, pharmacy chains will play a bigger role, many times linked to the distribution of the sector where profit prevails over service. With liberalization, some pharmacies in certain current locations would disappear, centralizing the offer. In addition, Spanish pharmacists strive to convey that they are providing a health service to society and are not carrying out a commercial activity, the sale of a product.

- (3)

- Regardless of our negative interpretation of the management policy of the pharmaceutical map of Spain, we detected some positive elements of the service offered in Spain. In fact, different bodies acknowledge the Spanish pharmacy as a historical example of public–private collaboration [34]. As we have exposed on several occasions throughout this paper, Spanish pharmacies provide a public service that is managed by private interests.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bailly, A.; Périat, M. Médicométrie: Une Nouvelle Aproche de la Santé; Económica: Paris, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gatrell, A. Geographies of Health: An Introduction; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 2002; Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Geographies+of+Health%3A+An+Introduction%2C+3rd+Edition-p-9780470672877 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Lewis, N.D.; Mayer, J.D. Disease as Natural Hazard. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1988, 12, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacione, M. (Ed.) Medical Geography: Progress and Prospect; Croom Helm: London, UK, 1986; Available online: https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.147553/2015.147553.Medical-Geography-Progress-And-Prospect_djvu.txt (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Haynes, R. The Geography of Health Services in Britain; Human Geography; Routledge Library Editions: London, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www.routledge.com/The-Geography-of-Health-Services-in-Britain/Haynes/p/book/9781138954786 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Crooks, V.; Andrews, G.; Pearce, J. Routledge Handbook of Health Geography. Routledge Handbook Online. 2018. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Routledge-Handbook-of-Health-Geography/Crooks-Andrews-Pearce/p/book/9781138098046 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Gesler, W.; Kearns, R. Culture/Place/Health.; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, P. The Slow Plague: A Geography of the AIDS Pandemic; Blackwell: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, H. (Ed.) Understanding Health Inequalities; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 2000; Available online: https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/7265894 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Santana, P. Geografias da Saúde e do Desenvolvimento. Evolução e Tendências em Portugal; Almedina Editorial: Coimbra, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B. Social Needs and Resources in Local Services; Michael Joseph: London, UK, 1968; Available online: https://kar.kent.ac.uk/27434/ (accessed on 5 March 2020).

- Harvey, D. Social Justice and the City; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, P.; Davidson, N.; Black, D.; Whitehead, M. Inequalities in Health: The Black Report. The Health Divide; Penguin Books Ltd.: London, UK, 1992; p. 450. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A. Location-Allocation Systems: A Review. Geogr. Anal. 1970, 2, 95–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, R.L. The Spatial Organisation of Society; Duxburg Press: Belmont, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Mcallister, D. Equity and Efficiency in Public Facility Location. Geogr. Anal. 1976, 8, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, V. Medicine under Capitalism; Prodist: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, J.F. Restructuring Privatization and the Geography of Health Care Provision in England, 1983–1987; Queen Mary College: London, UK, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, P. Acessibilidade e Utilização dos serviços de saúde. Ensaio metodológico em Geografia da Saúde; CCRC/ARSC: Coimbra, Portugal, 1995; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10316/631 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Mayhew, L. Urban Hospital Location; Urban Planning; Routledge Library Editions: London, UK, 2018; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326010380_Urban_Hospital_Location (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Agbonifo, P.O. The State of Health as a Reflection of the Level of Development of a Nation. Soc. Sci. Med. 1983, 17, 2003–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, D. The trilogy of distance, speed and time. J. Transp. Geogr. 2011, 19, 950–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravitz, R.; Paterniti, D.; Epstein, R.; Rochlen, A.; Bell, R.; Cipri, C.; Garcia, E.; Feldman, M.; Duberstein, P. Relational barriers to depression helpseeking in primary care. Patient Educ. Couns. 2011, 82, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, A.E.; Phillips, D.R. Accessibilty & Utilization. Geographical Perspectives on Health Care Delivery; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1984; Available online: https://researchers.mq.edu.au/en/publications/accessibility-and-utilization-geographical-perspectives-on-health (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Garb, J.; Wait, R. Using Spatial Analysis to Improve Health Care Services and Delivery at Baystate Health. J. Map Geogr. Libr. 2011, 7, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleindorfer, D.; Xu, Y.; Moomaw, C.; Khatri, P.; Adeoye, O.; Hornung, R. US geographic distribution of rt-PA utilization by hospital for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2009, 40, 3580–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moïsi, J.; Nokes, D.; Gatakaa, H.; Williams, T.; Bauni, E.; Levine, O.; Scott, J. Sensitivity of hospital-based surveillance for severe disease: A geographic information system analysis of access to care in Kilifi district, Kenya. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mclaren, Z.; Ardington, C.; Leibbrandt, M. Distance as a Barrier to Health Care Access in South Africa; Working Paper Series, 97; Labour and Development Research: Cape Town, Southern Africa, 2013; Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/scripts/redir.pf?u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.opensaldru.uct.ac.za%2Fbitstream%2Fhandle%2F11090%2F613%2F2013_97.pdf%3Fsequence%3D1;h=repec:ldr:wpaper:097 (accessed on 12 April 2020).

- Fujita, M.; Krugman, P. The new economic geography: Past, present and the future. In Fifty Years of Regional Science. Advances in Spatial Science; Florax, R.J.G.M., Plane, D.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miramontes Carballada, Á. Territorial assessment for moving a chemist’s in Galicia. A case study of Applied Geography. Rev. Galega De Econ. 2020, 29, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, S.J. Integrating multicriteria evaluation with geographical information systems. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 1991, 5, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo, J. Aplicación de Técnicas de Análisis Espacial Integrando Evaluación multi-Criterio y Sistemas de Información Geográfica Para la Realización de Estudios de Localización/Asignación de Actividades; Universidad de Alcalá de Henares, Alcalá de Henares: Madrid, Spain, 1997; Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=113902 (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- Bosque, J.; Moreno, A. Sistemas de Información Geográfica y Localización Óptima de Instalaciones y Equipamientos; RA-MA Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 2004; Available online: http://www.ra-ma.es/libros/sistemas-de-informacion-geografica-y-localizacion-optima-de-instalaciones-y-equipamientos (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos. Estadísticas de Colegiados y Farmacias Comunitarias 2017; Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Farmacéuticos: Madrid, Spain, 2019; Available online: https://www.portalfarma.com/ (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- González, I.; Bara, M.P. Modelos de farmaciaen la Unión Europea. Análisis comparativo. Farm. Prof. 2008, 22, 10–15. Available online: https://www.elsevier.es/es-revista-farmacia-profesional-3-articulo-modelos-farmacia-union-europea-analisis-13126015 (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- Vidal Casero, M.C. Derecho Farmacéutico: Legislación, Jurisprudencia, el Ejercicio Profesional; Ediciones Revista General de Derecho: Valecia, Spain, 2007; p. 1089. [Google Scholar]

- Ratiopharm. 2020. Available online: https://ratiopharm.es/ (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- General Council and the Pharmaceutical Group of the European Union (PGEU). Informes y Estadísticas Anuales. 2019. Available online: https://www.portalfarma.com/Profesionales/consejoinforma/Paginas/Libro-Blanco-Farmacia-Europa-PGEU.aspx (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Farmaconsulting. 2019. Available online: https://www.farmaconsulting.es/ (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- FarmaQuatrium. 2019. Available online: https://www.farmaquatrium.es/ (accessed on 9 August 2020).

- Instituto Galego de Estatística. Padrón Municipal de Habitantes. Santiago de Compostela, Spain. 2019. Available online: https://www.ige.eu/web/mostrar_actividade_estatistica.jsp?idioma=gl&codigo=0201001002 (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- IQVIA. Evolución del Mercado de la Farmacia Española 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/cese/spain/monthly-report/2019/iqvia_informefarmacias_enero2020.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

| Ownership | Demographic Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Spain | Limited to pharmacists. One pharmacy per licensee | Each Autonomous Region establishes its own criteria |

| Italy | Limited to pharmacists. Four pharmacies per licensee | In municipalities with a population: More than 12,500 inhabitants: One pharmacy/5000 inhabitants Less than 12,500 inhabitants: One pharmacy/4000 inhabitants |

| Netherlands | Not limited to pharmacists if managed by a pharmacist | Rural doctors prescribe and dispense their prescriptions. The closest pharmacy is more than 4.5 km away |

| Denmark | Limited to pharmacists and has to be managed by the owner | Administrative license that expires (retirement or death). The relocation of pharmacies is not allowed. It is accessed by calling a merit contest for pharmacists |

| Austria | Not limited to pharmacists | One pharmacy/5500 inhabitants The municipality must have a medical center |

| Annual Turnover | Number of Pharmacies | Average Turnover (Euros/Year) |

|---|---|---|

| More than 1.2 million | 4428 | 1,648,369 |

| 650,000 to 1,200,000 | 8880 | 913,432 |

| Less than 650,000 | 8830 | 477,121 1 |

| Population/Pharmacies | |

|---|---|

| Melilla | 3927 |

| Ceuta | 3548 |

| Canary Islands | 2792 |

| Basque Country | 2643 |

| Murcia | 2603 |

| Balearic Islands | 2577 |

| Cantabria | 2469 |

| Catalonia | 2378 |

| Madrid | 2299 |

| Asturias | 2260 |

| Andalusia | 2162 |

| Spain Average | 2121 |

| Comunitat Valenciana | 2105 |

| Rioja, La | 2024 |

| Galicia | 2010 |

| Aragon | 1783 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 1602 |

| Extremadura | 1599 |

| Castilla y Leon | 1480 |

| Navarra | 1077 |

| Criteria (Analysed) | Objective |

|---|---|

| Territorial legislation and regulations | Know the urban planning of the territory (partial, special plans, etc.). |

| Population structure | Mainly, take into account the strata of the aging population. |

| Economic structure | Detect the economic potentialities and weaknesses of the territory. The need for better care in vulnerable or poorer spaces. |

| Social culture | Know the idiosyncrasies and customs of the population. Introduce qualitative criteria for the consumption of the pharmaceutical products. |

| Population distribution | Focused on variables of density, distances, number of settlements, etc. |

| Provision of services and infrastructures | Linked to criteria of daily mobility or for working reasons. |

| Provision of health services and infrastructure | Characterisation of health services. |

| As a rule, work with percentages and trends on the space’s population and economic structure and not whole values. | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miramontes Carballada, Á.; Lois-González, R.C. Liberalization and Governance in the Geographical Distribution of Pharmacies in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010034

Miramontes Carballada Á, Lois-González RC. Liberalization and Governance in the Geographical Distribution of Pharmacies in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010034

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiramontes Carballada, Ángel, and Rubén C. Lois-González. 2022. "Liberalization and Governance in the Geographical Distribution of Pharmacies in Spain" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010034

APA StyleMiramontes Carballada, Á., & Lois-González, R. C. (2022). Liberalization and Governance in the Geographical Distribution of Pharmacies in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010034