Understanding and Measuring Help-Seeking Barriers among Intimate Partner Violence Survivors: Mixed-Methods Validation Study of the Icelandic Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma (BHS-TR) Scale

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Intimate Partner Violence against Women

1.2. Barriers to Help-Seeking

1.3. Existing Measures

1.4. The Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma Scale

1.5. Study Aims

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

2.2.1. Qualitative Phase

2.2.2. Quantitative Phase

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. The Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma (BHS-TR) Scale

2.4.2. Patient Health Questionnaire

2.4.3. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist for DSM-5

2.4.4. Beliefs toward Mental Illness Scale

2.4.5. Orientation to Life Questionnaire

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Qualitative Phase

Item Generation

Pretesting the New Items

2.5.2. Quantitative Phase

Factor Structure and Dimensionality

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Known-Groups Validity

Reliability

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Phase

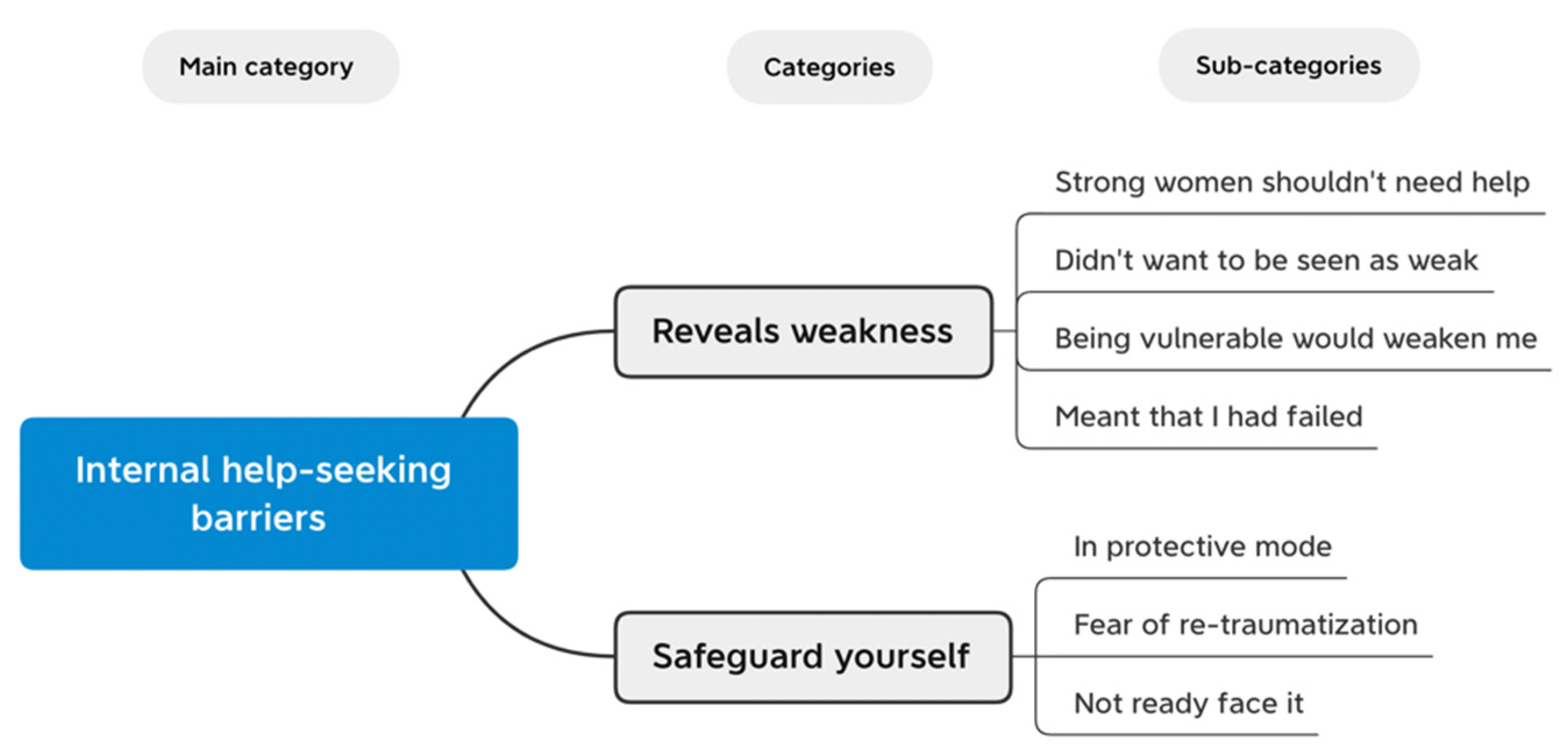

3.1.1. Reveals Weakness

3.1.2. Safeguard Yourself

3.1.3. Pretesting the New Items

3.2. Quantitative Phase

3.2.1. Participants’ Characteristics, Health Status, and Help-Seeking

3.2.2. Construct Validity

Factor Structure

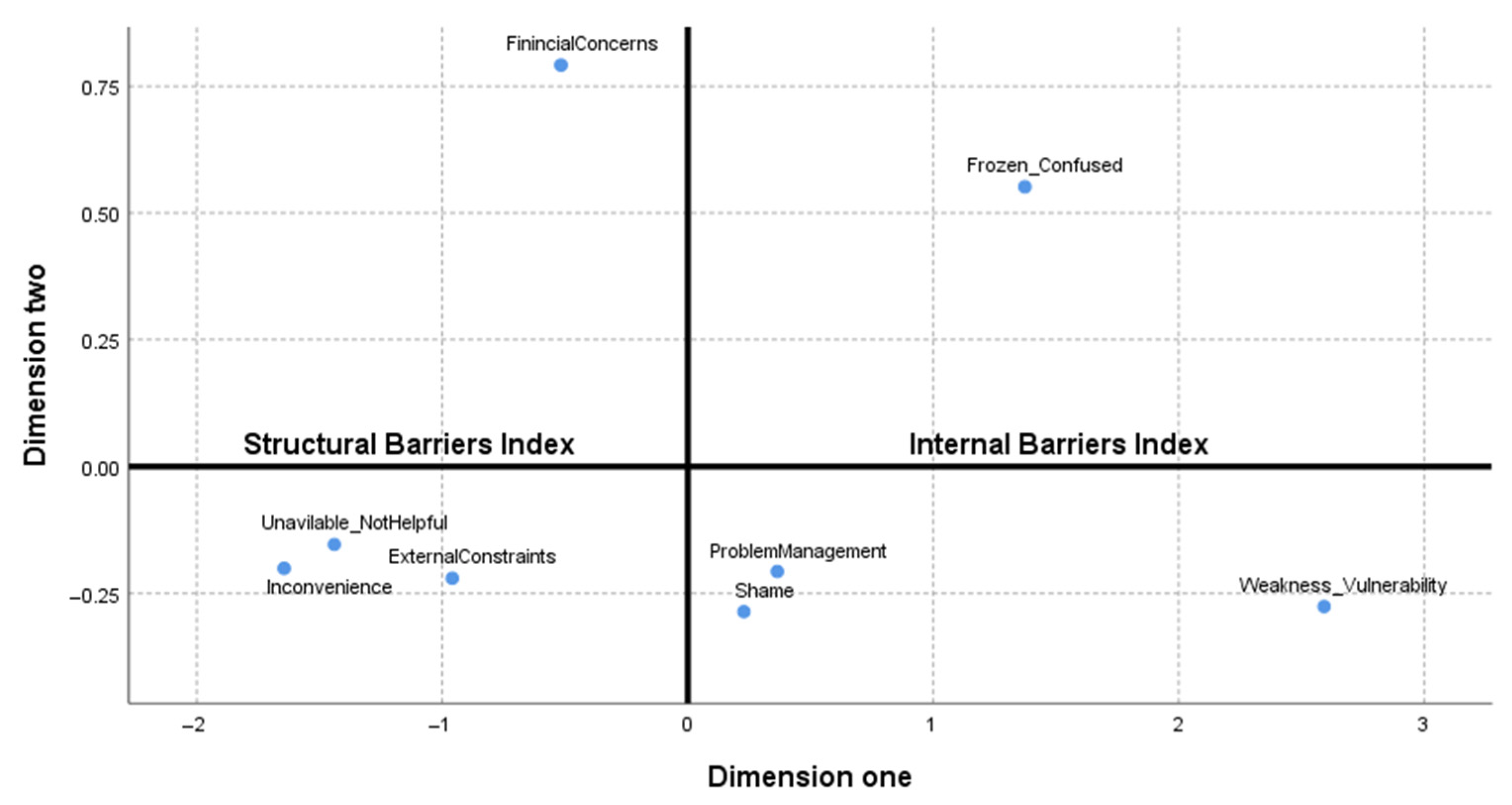

Structural and Internal Barriers Indices

Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Known-Groups Validity

3.2.3. Reliability

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Devries, K.M.; Mak, J.Y.T.; García-Moreno, C.; Petzold, M.; Child, J.C.; Falder, G.; Lim, S.; Bacchus, L.J.; Engell, R.E.; Rosenfeld, L.; et al. The Global Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence against Women. Science 2013, 340, 1527–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN Women. Gender Equality—Women’s Rights in Review 25 Years after Beijing; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-92-1-127072-3. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women: Initial Results on Prevalence, Health Outcomes and Women’s Responses; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005; ISBN 92-4-159358-X. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-Partner Sexual Violence against Women; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-002225-6. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, M.A.; Green, B.L.; Kaltman, S.I.; Roesch, D.M.; Zeffiro, T.A.; Krause, E.D. Intimate Partner Violence, PTSD, and Adverse Health Outcomes. J. Interpers. Violence 2006, 21, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Moreno, C.; Pallitto, C.; Devries, K.; Stöckl, H.; Watts, C.; Abrahams, N. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013; ISBN 978-92-4-156462-5. [Google Scholar]

- Hisasue, T.; Kruse, M.; Raitanen, J.; Paavilainen, E.; Rissanen, P. Quality of Life, Psychological Distress and Violence among Women in Close Relationships: A Population-Based Study in Finland. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdardottir, S.; Halldorsdottir, S. Persistent Suffering: The Serious Consequences of Sexual Violence against Women and Girls, their Search for Inner Healing and the Significance of the #MeToo Movement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Shamrova, D.; Han, J.; Levchenko, P. Patterns of Intimate Partner Violence Victimization and Survivors’ Help-Seeking. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 4558–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodson, A.; Hayes, B.E. Help-Seeking Behaviors of Intimate Partner Violence Victims: A Cross-National Analysis in Developing Nations. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 4705–4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lövestad, S.; Vaez, M.; Löve, J.; Hensing, G.; Krantz, G. Intimate Partner Violence, Associations with Perceived Need for Help and Health Care Utilization: A Population-Based Sample of Women in Sweden. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, B.J.; Peirone, A.; Cheung, C.H. Help Seeking Experiences of Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence in Canada: The Role of Gender, Violence Severity, and Social Belonging. J. Fam. Violence 2020, 35, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanslow, J.L.; Robinson, E.M. Help-Seeking Behaviors and Reasons for Help Seeking Reported by a Representative Sample of Women Victims of Intimate Partner Violence in New Zealand. J. Interpers. Violence 2010, 25, 929–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Heimer, G.; Lucas, S. Violence and Health in Sweden: A National Prevalence Study on Exposure to Violence among Women and Men and Its Association to Health; The National Centre for Knowledge on Men’s Violence against Women: Uppsala, Sweden, 2014; ISSN 1654-7195. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Violence against Women: An EU-Wide Survey—Main Results; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2014; ISBN 978-92-9239-999-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Welfare. Male Violence against Women in Intimate Relationships in Iceland; Ministry of Welfare: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2012; ISBN 978-9979-799-48-1.

- Heywood, I.; Sammut, D.; Bradbury-Jones, C. A Qualitative Exploration of ‘Thrivership’ among Women Who have Experienced Domestic Violence and Abuse: Development of a New Model. BMC Women’s Health 2019, 19, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelaurain, S.; Graziani, P.; Lo Monaco, G. Intimate Partner Violence and Help-Seeking A Systematic Review and Social Psychological Tracks for Future Research. Eur. Psychol. 2017, 22, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinko, L.; Goldner, L.; Saint Arnault, D.M. The Trauma Recovery Actions Checklist: Applying Mixed Methods to a Holistic Gender-Based Violence Recovery Actions Measure. Sexes 2021, 2, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heron, R.L.; Eisma, M.C. Barriers and Facilitators of Disclosing Domestic Violence to the Healthcare Service: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Research. Health Soc. Care Community 2021, 29, 612–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overstreet, N.M.; Quinn, D.M. The Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model and Barriers to Help Seeking. Basic Appl. Soc. Psych. 2013, 35, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.R.; Ravi, K.; Voth Schrag, R.J. A Systematic Review of Barriers to Formal Help Seeking for Adult Survivors of IPV in the United States, 2005–2019. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020, 22, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinko, L.; Burns, C.J.; O’Halloran, S.; Saint Arnault, D.M. Trauma Recovery is Cultural: Understanding Shared and Different Healing Themes in Irish and American Survivors of Gender-Based Violence. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 7765–7790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, C.E.; Resick, P.A. Help-Seeking Behavior in Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: Toward an Integrated Behavioral Model of Individual Factors. Violence Vict. 2017, 32, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hien, D.; Ruglass, L. Interpersonal Partner Violence and Women in the United States: An Overview of Prevalence Rates, Psychiatric Correlates and Consequences and Barriers to Help Seeking. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2009, 32, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saint Arnault, D.M.; O’Halloran, S. Using Mixed Methods to Understand the Healing Trajectory for Rural Irish Women Years after Leaving Abuse. J. Res. Nurs. 2016, 21, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Schauman, O.; Graham, T.; Maggioni, F.; Evans-Lacko, S.; Bezborodovs, N.; Morgan, C.; Rüsch, N.; Brown, J.S.L.; Thornicroft, G. What is the Impact of Mental Health-Related Stigma on Help-Seeking? A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockery, L.; Jeffery, D.; Schauman, O.; Williams, P.; Farrelly, S.; Bonnington, O.; Gabbidon, J.; Lassman, F.; Szmukler, G.; Thornicroft, G.; et al. Stigma- and Non-Stigma-Related Treatment Barriers to Mental Healthcare Reported by Service Users and Caregivers. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 228, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; McGrath, P.J.; Hayden, J.; Kutcher, S. Mental Health Literacy Measures Evaluating Knowledge, Attitudes and Help-Seeking: A Scoping Review. BMC Psychiatry 2015, 15, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, E.; Turner, J. Orientations to Seeking Professional Help: Development and Research Utility of an Attitude Scale. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1970, 35, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divin, N.; Harper, P.; Curran, E.; Corry, D.; Leavey, G. Help-Seeking Measures and their use in Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2018, 3, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, S.; Brohan, E.; Jeffery, D.; Henderson, C.; Hatch, S.L.; Thornicroft, G. Development and Psychometric Properties the Barriers to Access to Care Evaluation Scale (BACE) Related to People with Mental Ill Health. BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, M.H.; Offord, D.R.; Campbell, D.; Catlin, G.; Goering, P.; Lin, E.; Racine, Y.A. Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey: Methodology. Can. J. Psychiat. 1996, 41, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint Arnault, D.M.; Özaslan, Z.Z. Understanding help-seeking barriers after Gender-Based Violence: Validation of the Barriers to Help Seeking-Trauma version (BHS-TR). Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorvaldsdottir, K.B.; Halldorsdottir, S.; Johnson, R.M.; Sigurdardottir, S.; Saint Arnault, D.M. Adaptation of the Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma (BHS-TR) Scale: A Cross-Cultural Cognitive Interview Study with Female Intimate Partner Violence Survivors in Iceland. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2021, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, G.O.; Neilands, T.B.; Frongillo, E.A.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H.R.; Young, S.L. Best Practices for Developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and Behavioral Research: A Primer. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ægisdóttir, S.; Gerstein, L.H.; Çinarbaş, D.C. Methodological Issues in Cross-Cultural Counseling Research. Couns. Psychol. 2008, 36, 188–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R.W. Cross-Cultural Research in Psychology. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1983, 34, 363–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781483344379. [Google Scholar]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving Integration in Mixed Methods Designs-Principles and Practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Johnson, R.B. The Validity Issue in Mixed Research. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 48–63. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, K.M.T.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Jiao, Q.G. A Mixed Methods Investigation of Mixed Methods Sampling Designs in Social and Health Science Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 267–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourangeau, R. Cognitive Sciences and Survey Methods. In Cognitive Aspects of Survey Methodology: Building a Bridge between Disciplines; Jabine, T., Straf, M., Tanur, J., Tourangeau, R., Eds.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1984; pp. 73–100. [Google Scholar]

- Willis, G.B. Research Synthesis the Practice of Cross-Cultural Cognitive Interviewing. Public Opin. Q. 2015, 79, 359–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K.; Strine, T.W.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W.; Berry, J.T.; Mokdad, A.H. The PHQ-8 as a Measure of Current Depression in the General Population. J. Affect. Disord. 2009, 114, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Levis, B.; Riehm, K.E.; Saadat, N.; Levis, A.W.; Azar, M.; Rice, D.B.; Boruff, J.; Cuijpers, P.; Gilbody, S.; et al. Equivalency of the Diagnostic Accuracy of the PHQ-8 and PHQ-9: A Systematic Review and Individual Participant Data Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björnsson, A.S.; Jónsdóttir, K.; Sigurðardóttir, S.; Wessman, I.; Sigurjónsdóttir, Ó.; Þórisdóttir, A.S.; Harðarson, J.P.; Arnkelsson, G. Psychometric Properties of the Icelandic Translations of the Sheehan Disability Scale, Quality of Life Scale and the Patient Health Questionnaire. J. Icel. Psychol. Assoc. 2018, 23, 91–100. (In Icelandic) [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, C.A.; Weathers, F.W.; Davis, M.T.; Witte, T.K.; Domino, J.L. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. J. Trauma. Stress 2015, 28, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovin, M.J.; Marx, B.P.; Weathers, F.W.; Gallagher, M.W.; Rodriguez, P.; Schnurr, P.P.; Keane, T.M. Psychometric Properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in Veterans. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortmann, J.H.; Jordan, A.H.; Weathers, F.W.; Resick, P.A.; Dondanville, K.A.; Hall-Clark, B.; Foa, E.B.; Young-McCaughan, S.; Yarvis, J.S.; Hembree, E.A.; et al. Psychometric Analysis of the PTSD Checklist-5 (PCL-5) among Treatment-Seeking Military Service Members. Psychol. Assess. 2016, 28, 1392–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ásgeirsdóttir, J. Does Psychological Resilience Moderate the Relationship between Chronological Age, Threat Appraisal, Number of Traumatic Events and Trauma Type and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms? Master’s Thesis, University of Iceland, Reykjavík, Iceland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hirai, M.; Clum, G. Development, Reliability, and Validity of the Beliefs Toward Mental Illness Scale. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2000, 22, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, M.; Vernon, L.L.; Clum, G.A. Factor Structure and Administration Measurement Invariance of the Beliefs toward Mental Illness Scale in Latino College Samples: Paper–Pencil versus Internet Administrations. Assessment 2018, 25, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint Arnault, D.M.; Gang, M.; Woo, S. Construct Validity and Reliability of the Beliefs toward Mental Illness Scale for American, Japanese, and Korean Women. Res. Theory Nurs. Pract. 2017, 31, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonovsky, A. The Structure and Properties of the Sense of Coherence Scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993, 36, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health: How People Manage Stress and Stay Well; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1987; ISBN 978-1555420284. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. Antonovsky’s Sense of Coherence Scale and the Relation with Health: A Systematic Review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 376–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, S.; Wagemakers, M.A.E.; Picavet, H.S.J.; Verkooijen, K.T.; Koelen, M.A. Strengthening Sense of Coherence: Opportunities for Theory Building in Health Promotion. Health Promot. Int. 2016, 31, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M.; Lindström, B. Validity of Antonovsky’s Sense of Coherence Scale: A Systematic Review. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2005, 59, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmefur, M.; Sundberg, K.; Wettergren, L.; Langius-Eklöf, A. Measurement Properties of the 13-Item Sense of Coherence Scale using Rasch Analysis. Qual. Life Res. 2015, 24, 1455–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svavarsdottir, E.K.; Rayens, M.K. Hardiness in Families of Young Children with Asthma. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 50, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84920-592-4. [Google Scholar]

- Saint Arnault, D.M. Defining and Theorizing about Culture the Evolution of the Cultural Determinants of Help-Seeking, Revised. Nurs. Res. 2018, 67, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018; ISBN 9781526445780. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for getting the most from Your Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, A.G.; Pearce, S. A Beginner’s Guide to Factor Analysis: Focusing on Exploratory Factor Analysis. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 2013, 9, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattell, R.B. The Scree Test for the Number of Factors. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1966, 1, 245–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An Index of Factorial Simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of Exploratory Factor Analysis in Psychological Research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0805802832. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D.L. Starting at the Beginning: An Introduction to Coefficient Alpha and Internal Consistency. J. Pers. Assess. 2003, 80, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daigneault, P.; Jacob, S. Unexpected but Most Welcome: Mixed Methods for the Validation and Revision of the Participatory Evaluation Measurement Instrument. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2014, 8, 6–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Bustamante, R.M.; Nelson, J.A. Mixed Research as a Tool for Developing Quantitative Instruments. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2010, 4, 56–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankofa, N.L. Transformativist Measurement Development Methodology: A Mixed Methods Approach to Scale Construction. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ægisdóttir, S.; Einarsdóttir, S. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of the Icelandic Beliefs about Psychological Services Scale (I-BAPS). Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2012, 1, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsdottir, S.; Vilhjalmsdottir, G.; Smaradottir, S.B.; Kjartansdottir, G.B. A Culture-Sensitive Approach in the Development of the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale in Iceland: Theoretical and Operational Considerations. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melgar Alcantud, P.; Campdepadrós-Cullell, R.; Fuentes-Pumarola, C.; Mut-Montalvà, E. ‘I Think I Will Need Help’: A Systematic Review of Who Facilitates the Recovery from Gender-based Violence and How They Do So. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantor, V.; Knefel, M.; Lueger-Schuster, B. Perceived Barriers and Facilitators of Mental Health Service Utilization in Adult Trauma Survivors: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 52, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, J.W. Imposed Etics-Emics-Derived Etics: The Operationalization of a Compelling Idea. Int. J. Psychol. 1989, 24, 721–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M.; Landis, L.; Riordan, K.; Naureckas, S.; Engel, B. Barriers to Domestic Violence Help Seeking—Implications for Intervention. Violence Against Women 2005, 11, 290–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisinga, R.N.; Grotenhuis, M.; Pelzer, B. The Reliability of a Two-Item Scale: Pearson, Cronbach or Spearman-Brown? Int. J. Public Health 2013, 58, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammstedt, B.; Beierlein, C. Can’t we make it any Shorter? The Limits of Personality Assessment and Ways to Overcome Them. J. Individ. Differ. 2014, 35, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellard-Gray, A.; Jeffrey, N.K.; Choubak, M.; Crann, S.E. Finding the Hidden Participant: Solutions for Recruiting Hidden, Hard-to-Reach, and Vulnerable Populations. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2015, 14, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Winter, J.C.F.; Dodou, D.; Wieringa, P.A. Exploratory Factor Analysis with Small Sample Sizes. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2009, 44, 147–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeish, D. Exploratory Factor Analysis with Small Samples and Missing Data. J. Pers. Assess. 2017, 99, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietgen, F.; Kjaran, J.I.; Halldórsdóttir, B.E. Power Dynamics and Internalized Oppression: Immigrant Women and Intimate Partner Violence in Iceland. In The Role of Universities in Addressing Societal Challenges and Fostering Democracy: Inclusion, Migration, and Education for Citizenship—Book of Abstracts; University of Akureyri, Iceland, 26 March 2021; Session 5B: Gender Aspects of Migration to Iceland, Paper 4; The Icelandic Centre for Research: Reykjavík, Iceland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Qual Phase (n = 17) | Quan Phase (n = 137) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 4 (23.5%) | 24 (17.5%) |

| 30–39 | 7 (41.2%) | 34 (24.8%) |

| 40–49 | 4 (23.5%) | 38 (27.7%) |

| 50–59 | 1 (5.9%) | 18 (13.1%) |

| 60+ | 1 (5.9%) | 6 (4.4%) |

| Not stated | – | 17 (12.4%) |

| Racial and ethnic background | ||

| Caucasian | 17 (100%) | – |

| Iceland-born | 16 (94.1%) | – |

| Foreign-born | 1 (5.9%) | – |

| Level of education | ||

| High school or less | 3 (17.6%) | 11 (8.0%) |

| Technical or junior college degree | 5 (29.4%) | 29 (21.2%) |

| University degree | 9 (52.9%) | 82 (59.9%) |

| Not stated | – | 15 (10.9%) |

| Employment status (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| Working | 12 (70.6%) | 88 (64.2%) |

| Unemployed or looking for work | 2 (11.8%) | 7 (5.1%) |

| Student | 5 (29.4%) | 26 (19.0%) |

| Homemaker | 1 (5.9%) | 3 (2.2%) |

| Unable to work due to sickness/disability | 3 (17.6%) | 20 (14.6%) |

| Other | – | 24 (17.5%) |

| Number of children | ||

| None | 5 (29.4%) | 24 (17.5%) |

| One or two | 9 (52.9%) | 59 (43.1%) |

| Three or more | 3 (17.6%) | 46 (33.6%) |

| Not stated | – | 8 (5.8%) |

| Current medical diagnosis (mental and/or physical) | ||

| No | 6 (35.3%) | 44 (32.1%) |

| Yes | 11 (64.7%) | 93 (67.9%) |

| History of receiving mental healthcare | ||

| No | 8 (47.1%) | 24 (17.5%) |

| Yes | 9 (52.9%) | 112 (81.8%) |

| Not stated | – | 1 (0.7%) |

| QCA Inductive Approach | Description of How Each Step Was Performed |

|---|---|

| Preparation phase | |

| Selecting the unit of analysis | In accordance with the aim of the study, it was decided to analyze the parts of the interviews where the women spoke about help-seeking barriers they thought were missing from the scale. |

| Making sense of the data and obtaining a whole | First, the transcribed material was read through several times without coding to become immersed in the data. |

| Organizing phase | |

| Open coding | The transcribed material was read through again, and this time paragraphs and phrases (meaning units) directly related to the phenomenon under study were highlighted, and headings written down in the margins. Next, the headings were collected onto coding sheets and categories freely generated. |

| Grouping and categorization | The initial categories were compared and grouped based on similarities and differences into broader higher-order categories. |

| Abstraction | Each category was defined and named according to its content. Sub-categories with similar meanings were then grouped to form categories, which were all classified under the main category. The analysis process was continued until new categories could no longer be formed. |

| Reporting phase | |

| Report on the process | Each step was thoroughly documented during the process, allowing tracking of all the decisions made. This article represents the final step, where the analysis and findings are reported. |

| Barriers Reveals Weakness | Meaning Units | Proposed New Items |

|---|---|---|

| Strong women shouldn’t need help | “It was so strong within me the need to be tough and keep going, needing help felt like a sign of weakness” “I wanted to feel strong, show some strength, we are supposed to be so hardy and resilient…you know Vikings or whatever, and I guess that some part of me believed that strong women shouldn’t need help” | I thought that strong people should not need help |

| Didn’t want to be seen as weak | “I didn’t want to be looked at as weak and then to have people treat me differently…you know, feel sorry for me” “I was scared of being seen as a weakling” | I was scared of being seen as weak |

| Being vulnerable would weaken me | “It was like I would somehow become less…I don’t like being vulnerable, and vulnerability is to me at least a big part of seeking help” “I felt like, if I would open up…you know about my feelings or whatever that it would weaken me” | I felt like opening up to my feelings would weaken me |

| Meant that I had failed | “It was like a defeat or something, like such a personal failure, and that’s why it took me such a long time to seek help, it wasn’t until I had nothing left” “To seek help would mean that I had ultimately lost, for him and what he did to be the reason I was so fucked up…and like still…I couldn’t bear it” | Getting help would mean that I had failed or had been defeated |

| Barriers Safeguard Yourself | Meaning Units | Proposed New Items |

|---|---|---|

| In protective mode | “I wanted to protect myself, and I was in this mode that I just could not deal with it and needed to let myself be there…but you shouldn’t stay there for too long, you can get stuck” “I didn’t want to take the chance of regretting it. You know if I would seek help, and I wouldn’t be believed, or it wouldn’t be taken seriously, I was dealing with enough” | I did not seek help in an effort to protect or safeguard myself |

| Fear of re-traumatization | “I had made my world trigger-free, so yeah, I was really isolated but it was easier that way, and I just didn’t see the point…to go there, talking about it would only hurt me even more” “I was afraid that it would be too difficult for me because then I had to think about it, talk about it, recall these painful memories, and there was no way that I could do that” | I was afraid that seeking help would be too emotionally difficult or hurt me even more |

| Not ready to face it | “The desire to be whole was so strong, and if I had to get help, that would mean that I wasn’t whole anymore…of course, deep down, I knew I was broken, but I wasn’t ready to admit it” “Denial was a huge barrier for me, because you know, staying in denial doesn’t hurt as much…if you seek help, you need to face your experience” | Seeking help would require acknowledging things I did not want to face |

| Dropped Items |

|---|

| From the original mental healthcare scale |

| 3. I was unsure about where to go for help or how to access help |

| 4. I thought help probably would not do any good |

| 9. I could not get time away from work or my family |

| 12. I was concerned that I would not be able to get help soon enough |

| 13. I was scared about being put into a hospital against my will |

| 20. I felt that my culture, background, or specific situation would not be understood |

| 21. Suitable professionals were not available to me |

| 22. The kind of help I needed was not available |

| 23. I felt that there would be prejudice or discrimination against me |

| From the trauma-specific additions |

| 31. I was afraid I would explain what I needed, and no one would help me anyway |

| 32. I felt that I could not trust people to help me |

| 33. I felt no one could understand or help me |

| From the cognitive interviews (emic) additions |

| 36. I was afraid that seeking help would be too emotionally difficult or hurt me even more |

| 37. I did not seek help in an effort to protect or safeguard myself |

| 38. I felt like opening up to my feelings would weaken me |

| Factors Items (Communalities) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weakness/Vulnerability (Cumulative % of Variance: 26.47; Eigenvalue: 6.88) | ||||||||

| 40. I thought that strong people should not need help (0.84) | 0.93 | |||||||

| 39. Getting help would mean that I had failed or had been defeated (0.81) | 0.83 | |||||||

| 35. I was scared of being seen as weak (0.79) | 0.72 | 0.22 | ||||||

| 41. Seeking help would require acknowledging things I did not want to face (0.68) | 0.69 | 0.34 | ||||||

| 24. I thought my situation was too personal or wanted to keep it private (0.50) | 0.40 | 0.27 | 0.27 | |||||

| Financial Concerns (Cumulative % of Variance: 37.96; Eigenvalue: 2.99) | ||||||||

| 2. I was concerned that the help I needed would be too expensive (0.80) | 0.87 | |||||||

| 19. The available health insurance would not cover the type of treatment I needed (0.78) | 0.85 | 0.28 | ||||||

| 18. I did not have adequate financial resources (0.81) | 0.82 | |||||||

| Unavailable/Not Helpful (Cumulative % of Variance: 45.98; Eigenvalue: 2.07) | ||||||||

| 15. I was not satisfied with the available services (0.75) | 0.87 | |||||||

| 16. I felt that the help available would not provide the type of treatment or help that was best for the problem (0.72) | 0.85 | |||||||

| 17. I had sought help before, but it did not help (0.60) | 0.61 | 0.32 | −0.24 | |||||

| External Constraints (Cumulative % of Variance: 53.06; Eigenvalue: 1.84) | ||||||||

| 14. I was worried that if others discovered my health problems or situation, I could lose my children, security, or housing (0.74) | 0.86 | |||||||

| 34. Others were preventing me from getting the help I needed (0.71) | 0.78 | |||||||

| 25. I was afraid of the consequences for myself, my children, or my family (0.71) | 0.72 | 0.32 | ||||||

| Problem Management Beliefs (Cumulative % of Variance: 58.38; Eigenvalue: 1.38) | ||||||||

| 1. I thought the problem would probably get better by itself (0.59) | 0.77 | |||||||

| 11. I thought the situation was normal or was not severe (0.69) | 0.21 | 0.62 | −0.34 | |||||

| 10. I wanted to or thought I should solve the problems on my own (0.64) | 0.58 | 0.31 | ||||||

| Frozen/Confused (Cumulative % of Variance: 63.54; Eigenvalue: 1.34) | ||||||||

| 29. I could not seem to clarify my feelings or know what I needed (0.83) | −0.91 | |||||||

| 30. I was afraid I could not clearly express what I needed (0.67) | 0.22 | −0.61 | ||||||

| 26. I was confused or unable to plan out all the details or steps (0.69) | 0.24 | −0.20 | −0.56 | 0.31 | ||||

| 27. I felt paralyzed or frozen and unable to get started (0.70) | 0.26 | 0.30 | −0.43 | 0.25 | ||||

| Inconvenience (Cumulative % of Variance: 68.08; Eigenvalue: 1.18) | ||||||||

| 5. I had distance or transportation problems (0.78) | −0.83 | |||||||

| 8. I thought getting help would take too much time or was inconvenient (0.64) | 0.27 | 0.22 | −0.60 | |||||

| Shame (Cumulative % of Variance: 72.14; Eigenvalue: 1.06) | ||||||||

| 6. I was concerned about what others might think (0.80) | 0.86 | |||||||

| 7. I was ashamed (0.72) | 0.79 | |||||||

| 28. I believed that people would judge me (0.75) | 0.75 | |||||||

| BHS-TR | Depression | PTSD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indices and Subscales | No (n = 80) | Probable (n = 57) | p | No (n = 75) | Probable (n = 62) | p |

| Structural Barriers | 20.4 (5.4) | 23.7 (7.7) | 0.00 | 20.5 (5.5) | 23.3 (7.5) | 0.01 |

| Financial Concerns | 7.0 (3.2) | 7.3 (3.4) | – | 6.9 (3.3) | 7.4 (3.2) | – |

| Unavailable/Not Helpful | 4.4 (2.0) | 5.5 (2.7) | 0.01 | 4.6 (2.2) | 5.1 (2.6) | – |

| External Constraints | 5.2 (2.5) | 6.7 (3.2) | 0.00 | 5.2 (2.6) | 6.6 (3.1) | 0.00 |

| Inconvenience | 3.8 (1.8) | 4.4 (1.9) | 0.05 | 3.7 (1.7) | 4.5 (2.0) | 0.02 |

| Internal Barriers | 39.9 (10.5) | 43.8 (9.9) | 0.03 | 39.8 (10.9) | 43.6 (9.5) | 0.04 |

| Weakness/Vulnerability | 12.6 (4.8) | 13.9 (4.7) | – | 12.6 (4.9) | 13.7 (4.7) | – |

| Problem Management Beliefs | 8.7 (2.5) | 9.0 (2.4) | – | 8.6 (2.7) | 9.1 (2.1) | – |

| Frozen/Confused | 10.5 (3.4) | 12.3 (3.0) | 0.00 | 10.7 (3.6) | 12.0 (3.2) | 0.03 |

| Shame | 8.0 (2.9) | 8.6 (3.0) | – | 7.8 (3.0) | 8.8 (2.8) | 0.05 |

| Total | 60.3 (13.2) | 67.5 (15.0) | 0.00 | 60.3 (13.7) | 66.9 (14.3) | 0.00 |

| Indices and Subscales | Min. | Max. | M | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Barriers | 11 | 44 | 21.8 | 6.6 | 0.75 |

| Financial Concerns | 3 | 12 | 7.1 | 3.3 | 0.82 |

| Unavailable/Not Helpful | 3 | 12 | 4.8 | 2.4 | 0.71 |

| External Constraints | 3 | 12 | 5.8 | 2.9 | 0.77 |

| Inconvenience | 2 | 8 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 0.52 |

| Internal Barriers | 15 | 60 | 41.5 | 10.4 | 0.88 |

| Weakness/Vulnerability | 5 | 20 | 13.1 | 4.8 | 0.86 |

| Problem Management Beliefs | 3 | 12 | 8.8 | 2.5 | 0.62 |

| Frozen/Confused | 4 | 16 | 11.2 | 3.3 | 0.79 |

| Shame | 3 | 12 | 8.3 | 2.9 | 0.83 |

| Total | 26 | 104 | 63.3 | 14.3 | 0.87 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thorvaldsdottir, K.B.; Halldorsdottir, S.; Saint Arnault, D.M. Understanding and Measuring Help-Seeking Barriers among Intimate Partner Violence Survivors: Mixed-Methods Validation Study of the Icelandic Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma (BHS-TR) Scale. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010104

Thorvaldsdottir KB, Halldorsdottir S, Saint Arnault DM. Understanding and Measuring Help-Seeking Barriers among Intimate Partner Violence Survivors: Mixed-Methods Validation Study of the Icelandic Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma (BHS-TR) Scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010104

Chicago/Turabian StyleThorvaldsdottir, Karen Birna, Sigridur Halldorsdottir, and Denise M. Saint Arnault. 2022. "Understanding and Measuring Help-Seeking Barriers among Intimate Partner Violence Survivors: Mixed-Methods Validation Study of the Icelandic Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma (BHS-TR) Scale" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010104

APA StyleThorvaldsdottir, K. B., Halldorsdottir, S., & Saint Arnault, D. M. (2022). Understanding and Measuring Help-Seeking Barriers among Intimate Partner Violence Survivors: Mixed-Methods Validation Study of the Icelandic Barriers to Help-Seeking for Trauma (BHS-TR) Scale. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 104. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010104