Engaging New Parents in the Development of a Peer Nutrition Education Model Using Participatory Action Research

Abstract

:1. Introduction

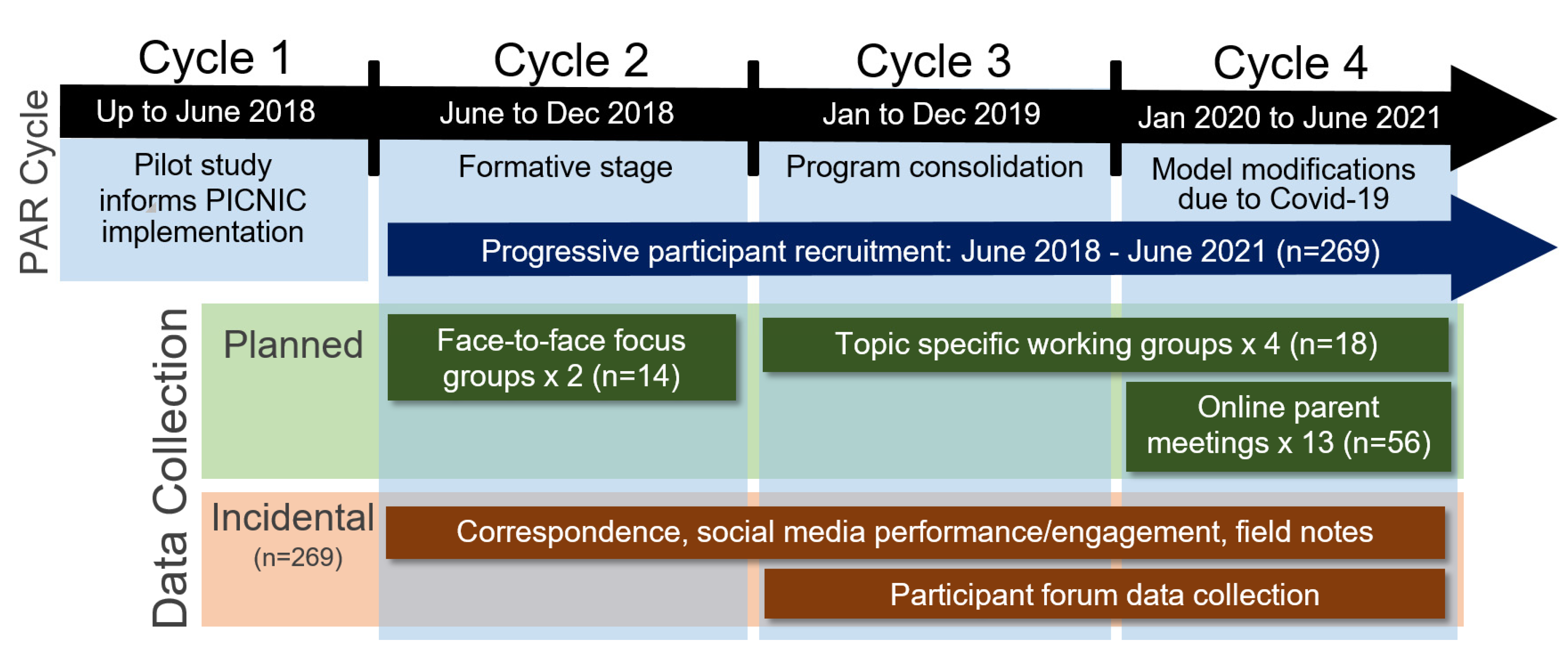

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodology and Design

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Reflexivity

2.6. Ethics Approval

3. Findings

3.1. Implementation Model Modifications

3.1.1. Peer ‘Sharing’ Enhances ‘End User’ Child Nutrition Information Uptake

“I’ve been chatting with the ladies in my mother’s group and a few of them are interested in the PICNIC project”.

“Again, I cannot rate the project highly enough. I’ve even directed my Queensland mum friends to the website”.

“My sister even asked me about her five-year-old. He’s quite a fussy eater. I said, go and have a look at the website and just get some hints and tips from there”.

“I felt a bit overwhelmed, like oh okay, now I feel there’s a little expectation that when I’m chatting with mums I need to be, I guess, disseminating information”.

“You’re going to be a peer educator, it all sounded like a lot more of a commitment than really what it is… without even realising you’re passing information on to people you talk to, just when it comes up in conversation”.

“So even if you’re not actively trying to spread the word, it still happens to whoever you’re talking to. Really when you’re first starting out those things you’re not talking about much else with other mums, other than what your babies are up to… so you end up sharing a lot of information quite easily”.

“I’m still here. Just taking it all in. It’s good to just listen to all this stuff because you know it’s coming”.

3.1.2. Impact of COVID-19

“I felt welcomed and not judged, I perceived the space as a safe place where I had the freedom to talk about my personal experiences/struggles, creating a sense of belonging, knowing that I was not the only one going through something”.

“Maybe a Three-session, so I could have taken that information away, let it simmer for a little while, and then at least have another one or two opportunities to chat”.

3.1.3. Digital Platforms for Sharing Evidence-Based Nutrition Information

“I know that the resources are there online, but I guess it’s finding the exact—because there is a lot of information which is good but it’s finding the exact thing that ties in best to be able to share and to show them which is a bit tricky”.

“Don’t create something where we have to go, come to where we are. We are already on Facebook. Most people share everything there”.

“Those little reminders would help me get back on track. No, no, no, we know not to just let him snack throughout the day. We know that there’s six mealtimes a day. Just that—the nice, simple little bits of advice that kept popping up in my feed”.

“I loved the picture that came up recently with the boy clearing the plate. … I shared that one … that got a few laughs”.

3.1.4. Participant Support Needs

“I came to the workshop, learned it all, then we chatted in our group and just did it… we all just chilled out”.

“Having him [Program manager] behind the wheel of that, he’s so personable and so knowledgeable, and as you [another participant] said, so approachable. I think he was the right person to start that off”.

“I value these chats because I go through that mum anxiety of, well she’s not eating much, she’s not doing what every other baby is doing. Last time I was feeling that and that really calmed me down to just say, well whatever goes”.

“Then when people did post their personal experiences, you’d have the professional come in and say, yes you’re on the right track, or perhaps look at this. “

“I agree with the whole—about the website, having everything, and then the Facebook feed being that live rolling of throwing in extra points every now and again, and sharing other people’s experiences”.

3.2. Research Model Transformation

3.2.1. Participant Recruitment

“Even those [parents] will still listen to some of the other posts that I shared back in our little mums’ group …so, still like the information, but getting them to join in…”

“… the people that I didn’t ask for a survey, the discussion went really well. The people that had to have that initial muck-around, they were a bit offside at the start”.

“Sometimes hearing another mum recommend a program can be really powerful, for me anyway”.

3.2.2. Quantitative Data Collection

“I know they’ve just changed the survey style and there’s just one survey now for any age group… that was a good change”.

“Everyone needs groceries. We’re all on mat leave or government pay or something like that. Job Keeper. It all helps”.

“The questions are a good reminder of the important points right now for us, we need to focus more on family meals”.

“I understand it’s a research project … but if that paperwork was completely taken out of the equation, then just the discussion side of it worked really well”.

4. Recommendations Informing PAR Cycle 5 and an Embedded PICNIC Model

“PICNIC Flyers would be a great inclusion. It would be great to have this information before the baby is even born”.

“Unfortunately, I didn’t gain much interest at all from my mothers’ group as they have been approached by the other [PICNIC] mums”.

“It would be a great way to not just reach parents, but educators in childcare settings are exposed to so many parents there, so if they could have the training too”.

“Also just wanted to commend the project/research design. My partner and I both have academic backgrounds and it’s great to see a research project that is not just ‘taking’ from participants but is really giving in the form of education and aiming to change behaviour in a positive way, while being transparent about its methods. ”

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ho, M.; Garnett, S.P.; Baur, L.; Burrows, T.; Stewart, L.; Neve, M.; Collins, C. Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: Systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e1647–e1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- AIHW. Nutrition across the Life Stages; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2018.

- Fox, M.K.; Pac, S.; Devaney, B.; Jankowski, L. Feeding infants and toddlers study: What foods are infants and toddlers eating? J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, s22–s30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birch, L.L. Child feeding practices and the etiology of obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006, 14, 343–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, C.; Duncanson, K.; Burrows, T. A systematic review investigating associations between parenting style and child feeding behaviours. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, J.; Maher, J.; Tanner, C. Social class, anxieties and mothers’ foodwork. Sociol. Health Illn. 2015, 37, 422–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, M. Child-rearing difficulties reported by parents of infants and toddlers. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1996, 21, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duncanson, K.; Burrows, T.; Holman, B.; Collins, C. Parents’ Perceptions of Child Feeding: A Qualitative Study Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 2013, 34, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agras, W.S.; Kraemer, H.C.; Berkowitz, R.I.; Hammer, L.D. Influence of early feeding style on adiposity at 6 years of age. J. Pediatr. 1990, 116, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, P.; O’Dea, J.A.; Battisti, R. Child feeding practices and perceptions of childhood overweight and childhood obesity risk among mothers of preschool children. Nutr. Diet. 2007, 64, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gevers, D.W.; Kremers, S.P.; de Vries, N.K.; van Assema, P. Patterns of Food Parenting Practices and Children’s Intake of Energy-Dense Snack Foods. Nutrients 2015, 7, 4093–4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, J.S.; Fisher, J.O.; Birch, L.L. Parental influence on eating behavior: Conception to adolescence. J. Law Med. Ethics 2007, 35, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Birch, L.L.; Fisher, J.O.; Davison, K.K. Learning to overeat: Maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls’ eating in the absence of hunger. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 78, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, R.; Duncanson, K.; Burrows, T.; Collins, C. Experiences of Parent Peer Nutrition Educators Sharing Child Feeding and Nutrition Information. Children (Basel) 2017, 4, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Graham, V.G.K.; Marraffa, C.; Henry, L. ‘Filling the gap’—Children aged two years or less: Sources of nutrition information used by families and maternal and child health nurses. Austr. J. Nutr. Diet. 1999, 56, 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Duncanson, K.; Burrows, T.; Collins, C. Peer education is a feasible method of disseminating information related to child nutrition and feeding between new mothers. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buller, D.B.; Morrill, C.; Taren, D.; Aickin, M.; Sennott-Miller, L.; Buller, M.K.; Larkey, L.; Alatorre, C.; Wentzel, T.M. Randomized trial testing the effect of peer education at increasing fruit and vegetable intake. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1999, 91, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cameron, A.J.; Hesketh, K.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D.; Campbell, K.J. Influence of peers on breastfeeding discontinuation among new parents: The Melbourne InFANT Program. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e601–e607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rempel, L.A.; Moore, K.C. Peer-led prenatal breast-feeding education: A viable alternative to nurse-led education. Midwifery 2012, 28, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfinger, J.Z.; Arniella, G.; Wylie-Rosett, J.; Horowitz, C.R. Project HEAL: Peer education leads to weight loss in Harlem. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2008, 19, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.; Food Standards, A. Peer-led approaches to dietary change: Report of the Food Standards Agency seminar held on 19 July 2006. Public Health Nutr. 2007, 10, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, S.; Park, Y.S.; Israel, T.; Cordero, E.D. Longitudinal evaluation of peer health education on a college campus: Impact on health behaviors. J. Am. Coll. Health J. ACH 2009, 57, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, D.; Rankin, P.; Morey, P.; Kent, L.; Hurlow, T.; Chang, E.; Diehl, H. The effectiveness of the Complete Health Improvement Program. (CHIP) in Australasia for reducing selected chronic disease risk factors: A feasibility study. N. Z. Med. J. 2013, 126, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.D.; Devjani, S.; Chillakanti, M.; Dunton, G.F.; Mason, T.B. The COMET study: Examining the effects of COVID-19-related perceived stress on Los Angeles Mothers’ dysregulated eating behaviors, child feeding practices, and body mass index. Appetite 2021, 163, 105209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, R.; Vaschak, R.; Bailey, A.; Whiteford, G.; Burrows, T.L.; Duncanson, K.; Collins, C.E. Study Protocol of the Parents in Child Nutrition Informing Community (PICNIC) Peer Education Cohort Study to Improve Child Feeding and Dietary Intake of Children Aged Six Months to Three Years Old. Children (Basel) 2019, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feilzer, M. Doing Mixed Methods Research Pragmatically: Implications for the Rediscovery of Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm. J. Mixed Methods Res. 2010, 4, 6–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, F.; MacDougall, C.; Smith, D. Participatory action research. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2006, 60, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morris, Z.S.; Wooding, S.; Grant, J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: Understanding time lags in translational research. J. R. Soc. Med. 2011, 104, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mid North Coast Local Health District. Parents in Child Feeding Informing Commmunity. Available online: https://www.picnicproject.com.au/ (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Walsh, A.; Kearney, L.; Dennis, N. Factors influencing first-time mothers’ introduction of complementary foods: A qualitative exploration. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doraiswamy, S.; Abraham, A.; Mamtani, R.; Cheema, S. Use of Telehealth During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Scoping Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e24087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, L.K.; Collins, C.E.; May, C.; Ashman, A.; Holder, C.; Brown, L.J.; Burrows, T.L. Feasibility and efficacy of a web-based family telehealth nutrition intervention to improve child weight status and dietary intake: A pilot randomised controlled trial. J. Telemed Telecare 2021, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Bragg, J.; Reay, R.E. Pivot to Telehealth: Narrative Reflections on Circle of Security Parenting Groups during COVID-19. Aust. N. Z. J. Fam. Ther. 2021, 42, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarnowiecki, D.; Mauch, C.E.; Middleton, G.; Matwiejczyk, L.; Watson, W.L.; Dibbs, J.; Dessaix, A.; Golley, R.K. A systematic evaluation of digital nutrition promotion websites and apps for supporting parents to influence children’s nutrition. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, A.J.; Charlton, E.; Walsh, A.; Hesketh, K.; Campbell, K. The influence of the maternal peer group (partner, friends, mothers’ group, family) on mothers’ attitudes to obesity-related behaviours of their children. BMC Pediatr. 2019, 19, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giustini, D.; Ali, S.M.; Fraser, M.; Kamel Boulos, M.N. Effective uses of social media in public health and medicine: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Online J. Public Health Inform. 2018, 10, e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mid North Coast Local Health District. Strategic Directions 2017–2021. 2017. Available online: https://mnclhd.health.nsw.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/127044570_MNCLHD_Strategic-Directions-2017-2021_v7-1-1.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Burrows, T.L.; Collins, K.; Watson, J.; Guest, M.; Boggess, M.M.; Neve, M.; Rollo, M.; Duncanson, K.; Collins, C.E. Validity of the Australian Recommended Food Score as a diet quality index for Pre-schoolers. Nutr. J. 2014, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jansen, E.; Russell, C.; Appleton, J.; Byrne, R.; Daniels, L.; Fowler, C.; Rossiter, C.; Mallan, K. The Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire: Development and validation of age appropriate versions for infants and toddlers. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, L.L.; Mihrshahi, S.; Gale, J.; Nguyen, B.; Baur, L.A.; O’Hara, B.J. Translational research: Are community-based child obesity treatment programs scalable? BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Gender | Age-Range | Indigenous Status | Attend Parent Group | ||||

| Male | 5 (2%) | 18–24 years | 19 (9%) | Indigenous Australian Non-Indigenous Australian | 11 (5%) | No | 55 (26%) |

| Female | 261 (98%) | 25–34 years | 138 (68%) | 196 (95%) | Yes | 155 (74%) | |

| 35–44 years | 47 (23%) | ||||||

| Highest Education Level | Employment Status | No. of Children | Youngest Child | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 10 or equivalent | 9 (4%) | Not employed | 38 (18%) | 1 Child | 159 (76%) | 0–6 months | 104 (49%) |

| Year 12 or equivalent | 46 (22%) | Maternity leave | 100 (48%) | 2 Children | 35 (16%) | 6–12 months | 70 (33%) |

| Trade/Vocational | 25 (12%) | Part-time employed | 45 (22%) | 3–5 Children | 16 (8%) | 12–24 months | 37 (18%) |

| University degree | 122 (59%) | Full-time employed | 24 (12%) | ||||

| Other | 6 (3%) | ||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ball, R.; Duncanson, K.; Ashton, L.; Bailey, A.; Burrows, T.L.; Whiteford, G.; Henström, M.; Gerathy, R.; Walton, A.; Wehlow, J.; et al. Engaging New Parents in the Development of a Peer Nutrition Education Model Using Participatory Action Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010102

Ball R, Duncanson K, Ashton L, Bailey A, Burrows TL, Whiteford G, Henström M, Gerathy R, Walton A, Wehlow J, et al. Engaging New Parents in the Development of a Peer Nutrition Education Model Using Participatory Action Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleBall, Richard, Kerith Duncanson, Lee Ashton, Andrew Bailey, Tracy L. Burrows, Gail Whiteford, Maria Henström, Rachel Gerathy, Alison Walton, Jennifer Wehlow, and et al. 2022. "Engaging New Parents in the Development of a Peer Nutrition Education Model Using Participatory Action Research" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010102

APA StyleBall, R., Duncanson, K., Ashton, L., Bailey, A., Burrows, T. L., Whiteford, G., Henström, M., Gerathy, R., Walton, A., Wehlow, J., & Collins, C. E. (2022). Engaging New Parents in the Development of a Peer Nutrition Education Model Using Participatory Action Research. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010102