Hospitalizations and Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Urogenital Tuberculosis in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2016–2018

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. General Setting

2.3. Specific Setting

2.4. Study Population and Period

2.5. Variables, Definitions, Data Sources

2.6. Data Entry and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

3.2. Hospitalizations and Length of Stay

3.3. Factors Associated with Length of Stay

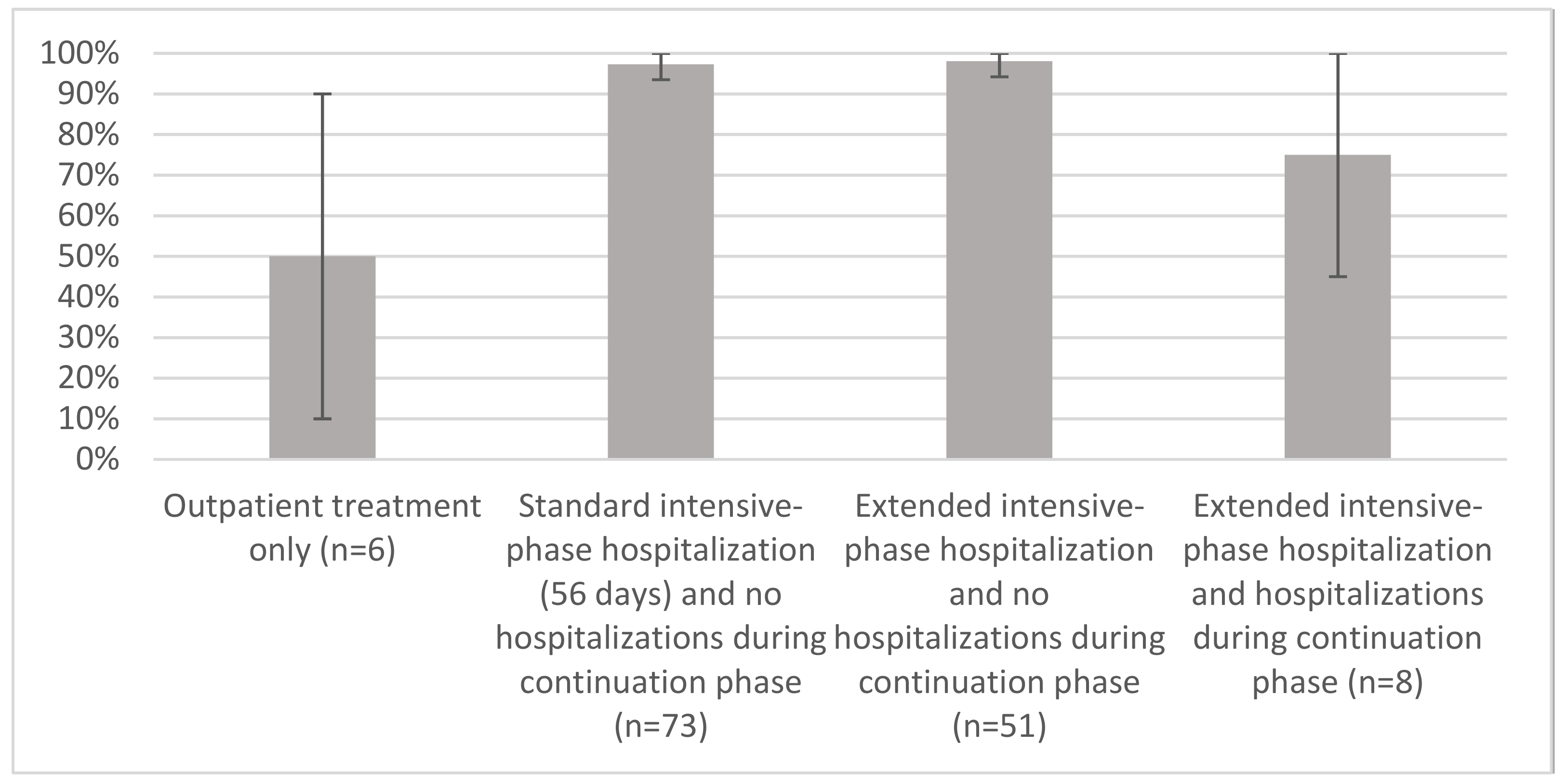

3.4. Treatment Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Disclaimer

Open Access Statement

Abbreviations

| BMI | body mass index |

| CI | confidence interval |

| DST | drug-susceptibility testing |

| HI | human immunodeficiency virus |

| IRR | incidence rate ratio calculated by negative binomial regression |

| LOS | length of stay |

| Q1 | 25th percentile |

| Q3 | 75th percentile |

| ref. | reference category |

| TB | tuberculosis |

| UGTB | urogenital tuberculosis |

Appendix A. Definition of Urogenital Tuberculosis Treatment Outcomes in Uzbekistan by the National Treatment Guidelines

| Treatment Outcome | Description |

| Cured | A patient with bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis at the beginning of treatment who was urine smear- or culture-negative in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion. |

| Treatment completed | A tuberculosis patient who completed treatment without evidence of failure but with no record to show that urine smear or culture results in the last month of treatment and on at least one previous occasion were negative, either because tests were not done or because results are unavailable. A patient with clinically diagnosed tuberculosis who did not have clinical symptoms at the end of treatment, such as normalization of urine, blood tests, and X-ray of the urinary tract. |

| Treatment failed | A patient with bacteriologically confirmed tuberculosis at the beginning of treatment whose urine smear or culture was positive at month 5 or later during treatment. A patient with clinically diagnosed tuberculosis who had deterioration of urine tests, blood tests, or X-ray of the urinary tract at month 5 or later during treatment. |

| Died | A tuberculosis patient who died for any reason before starting or during the course of treatment. |

| Lost to follow-up | A tuberculosis patient who did not start treatment or whose treatment was interrupted for 2 consecutive months or more. |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Tuberculosis Report 2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, A.A.; Lucon, A.M.; Junior, R.F.; Srougi, M. Epidemiology of urogenital tuberculosis worldwide. Int. J. Urol. 2008, 15, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S.; Sen, M.K.; Tyagi, J.S. Diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis by smear, culture, and PCR using universal sample processing technology. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 4357–4362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, M.; Mustafa, T. Laboratory diagnosis of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis (EPTB) in resource- constrained setting: State of the art, challenges and the need. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, EE01–EE06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastwood, J.B.; Corbishley, C.M.; Grange, J.M. Tuberculosis and the kidney. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2001, 12, 1307–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørstad, M.D.; Dyrhol-Riise, A.M.; Aßmus, J.; Marijani, M.; Sviland, L.; Mustafa, T. Evaluation of treatment response in extrapulmonary tuberculosis in a low-resource setting. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banta, J.E.; Ani, C.; Bvute, K.M.; Lloren, J.I.C.; Darnell, T.A. Pulmonary vs. extra-pulmonary tuberculosis hospitalizations in the US [1998–2014]. J. Infect. Public Health 2020, 13, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronald, L.A.; Fitzgerald, J.M.; Benedetti, A.; Boivin, J.-F.; Schwartzman, K.; Bartlett-Esquilant, G.; Menzies, D. Predictors of hospitalization of tuberculosis patients in Montreal, Canada: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, L.; Turner, M.; Haskal, R.; Etkind, S.; Tricarico, M.; Nardell, E. Long-term hospitalization for tuberculosis control. Experience with a medical-psychosocial inpatient unit. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1997, 278, 838–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirenga, B.J.; Levin, J.; Ayakaka, I.; Worodria, W.; Reilly, N.; Mumbowa, F.; Nabanjja, H.; Nyakoojo, G.; Fennelly, K.; Nakubulwa, S.; et al. Treatment outcomes of new tuberculosis patients hospitalized in Kampala, Uganda: A prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oscherwitz, T.; Tulsky, J.P.; Roger, S.; Sciortino, S.; Alpers, A.; Royce, S.; Lo, B. Detention of persistently nonadherent patients with tuberculosis. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1997, 278, 843–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetola, N.M.; Macesic, N.; Modongo, C.; Shin, S.; Ncube, R.; Collman, R.G. Longer hospital stay is associated with higher rates of tu-berculosis-related morbidity and mortality within 12 months after discharge in a referral hospital in Sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sadykova, L.; Abramavičius, S.; Maimakov, T.; Berikova, E.; Kurakbayev, K.; Carr, N.T.; Padaiga, Ž.; Naudžiūnas, A.; Stankevičius, E. A retrospective analysis of treatment outcomes of drug-susceptible TB in Kazakhstan, 2013–2016. Medicine 2019, 98, e16071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassili, A.; Fitzpatrick, C.; Qadeer, E.; Fatima, R.; Floyd, K.; Jaramillo, E. A systematic review of the effectiveness of hospital and am-bulatory-based management of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 89, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). A People-Centred Model of Tuberculosis Care: A Blueprint for Eastern European and Central Asian Countries, 1st ed.; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, S.; Asadov, D.A.; Bründer, A.; Healy, S.; Khamraev, A.K.; Sergeeva, N.; Tinnemann, P. Health system support and health system strengthening: Two key facilitators to the implementation of ambulatory tuberculosis treatment in Uzbekistan. Health Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wurtz, R.; White, W.D. The cost of tuberculosis: Utilization and estimated charges for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in a public health system. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 1999, 3, 382–387. [Google Scholar]

- Edlin, B.R.; Tokars, J.I.; Grieco, M.H.; Crawford, J.T.; Williams, J.; Sordillo, E.M.; Ong, K.R.; Kilburn, J.O.; Dooley, S.W.; Castro, K.G.; et al. An outbreak of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis among hospitalized patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 326, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.A.; Laraque, F.; Munsiff, S.; Piatek, A.; Harris, T.G. Hospitalizations for tuberculosis in New York City: How many could be avoided? Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2010, 14, 1603–1612. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators. DataBank. 2019. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=UZB (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis and Patient Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rawlins, M.; Thompson, W. Mechanisms of adverse drug reactions. In Textbook of Adverse Drug Reactions; Davies, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; pp. 18–45. [Google Scholar]

- Nutini, S.; Fiorenti, F.; Codecasa, L.R.; Casali, L.; Besozzi, G.; Di Pisa, G.; Nardini, S.; Migliori, G.B. Hospital admission policy for tuberculosis in pulmonary centres in Italy: A national survey. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 1999, 3, 985–991. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, F.M.; Atun, R.A.; Jakubowiak, W.; McKee, M.; Coker, R.J. Reform of tuberculosis control and DOTS within Russian public health systems: An ecological study. Eur. J. Public Health 2006, 17, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulchavenya, E.; Kholtobin, D. Diseases masking and delaying the diagnosis of urogenital tuberculosis. Ther. Adv. Urol. 2015, 7, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galego, M.A.; Santos, J.V.; Viana, J.; Freitas, A.; Duarte, R. To be or not to be hospitalised with tuberculosis in Portugal. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2019, 23, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Rojas, M.D.; Pérez, E.M.; Pérez, Á.M.; Cifuentes, S.V.; Villalba, E.G.; Campoy, M.D.L.; Sánchez, A.C.; Morell, E.B. Factors associated with a long mean hospital stay in patients hospitalized with tuberculosis. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2017, 53, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.J.F.; Ferreira, A.A.F. Factors associated with length of hospital stay among HIV positive and HIV negative patients with tuberculosis in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.C.; Seth, A.K.; Paul, M.; Puri, P. Risk factors of hepatotoxicity during anti-tuberculosis treatment. Med. J. Armed. Forces India 2006, 62, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bao, D.; Gu, L.; Gu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Gao, Z.; Huang, Y. Co-infection with hepatitis B virus among tuberculosis patients is associated with poor outcomes during anti-tuberculosis treatment. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wejse, C. Medical treatment for urogenital tuberculosis (UGTB). GMS Infect. Dis. 2018, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffman, S.A.; Veen, J.; Hennink, M.M.; McFarland, D.A. Exploitation, vulnerability to tuberculosis and access to treatment among Uzbek labor migrants in Kazakhstan. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 74, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, C.; Ferencic, N.; Malyuta, R.; Mimica, J.; Niemiec, T. Central Asia: Hotspot in the worldwide HIV epidemic. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkina, T.V.; Khojiev, D.S.; Tillyashaykhov, M.N.; Tigay, Z.N.; Kudenov, M.U.; Tebbens, J.D.; Vlcek, J. Delay in the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in Uzbekistan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, K.; Hutubessy, R.; Samyshkin, Y.; Korobitsyn, A.; Fedorin, I.; Volchenkov, G.; Kazeonny, B.; Coker, R.; Drobniewski, F.; Jakubowiak, W.; et al. Health-systems efficiency in the Russian Federation: Tuberculosis control. Bull. World Health Organ. 2006, 84, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Chen, J.; Sato, K.D.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wu, P.; Wang, H. Factors that associated with TB patient admission rate and TB inpatient service cost: A cross-sectional study in China. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2016, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasker, E.; Khodjikhanov, M.; Usarova, S.; Yuldasheva, U.; Uzakova, G.; Veen, J. Health-care seeking behaviour for TB symptoms in two provinces of Uzbekistan. Trop. Dr. 2008, 38, 107–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasker, E.; Khodjikhanov, M.; Usarova, S.; Asamidinov, U.; Yuldashova, U.; Van Der Werf, M.J.; Uzakova, G.; Veen, J. Default from tuberculosis treatment in Tashkent, Uzbekistan; Who are these defaulters and why do they default? BMC Infect. Dis. 2008, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Z.; Marks, S.M.; Burrows, N.M.R.; Weis, S.E.; Stricof, R.L.; Miller, B. Causes and costs of hospitalization of tuberculosis patients in the United States. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2000, 4, 931–939. [Google Scholar]

- Atun, R.; Samyshkin, Y.; Drobniewski, F.; Kuznetsov, S.; Fedorin, I.; Coker, R. Seasonal variation and hospital utilization for tuberculosis in Russia: Hospitals as social care institutions. Eur. J. Public Health 2005, 15, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heysell, S.K.; Shenoi, S.V.; Catterick, K.; Thomas, T.A.; Friedland, G. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage among hospitalised patients with tuberculosis in rural Kwazulu-Natal. S. Afr. Med. J. 2011, 101, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Li, L.; Li, W.; Hou, T.; Ma, H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, A.; Liu, Y.; Wen, J.; Yang, H.; et al. Impact of healthcare-associated infections on length of stay: A study in 68 hospitals in China. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics/Variables | N | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 142 | (100) | |

| Age, mean (SD) categories | Mean (SD, min–max) | 40 (16, 18–80) | |

| 18–34 | 67 | (47) | |

| 35–54 | 45 | (32) | |

| 55–80 | 30 | (21) | |

| Sex | Male | 77 | (54) |

| Female | 65 | (46) | |

| Type of residence | Urban | 29 | (20) |

| Rural | 113 | (80) | |

| Alcohol abuse | Yes | 3 | (2) |

| No/Not recorded | 139 | (98) | |

| Current tobacco smoking | Yes | 30 | (21) |

| No/Not recorded | 112 | (79) | |

| Labor migration to other countries in the past six months | Yes | 7 | (5) |

| No/Not recorded | 135 | (95) | |

| Bacteriological confirmation | Clinically diagnosed | 74 | (52) |

| Laboratory confirmed | 68 | (48) | |

| Urine microscopy at admission | M. tb detected | 9 | (6) |

| M. tb not detected | 133 | (94) | |

| Xpert MTB/RIF at admission | Rifampicin sensitive | 56 | (39) |

| M. tb not detected | 84 | (59) | |

| Not recorded | 2 | (2) | |

| Culture at admission | M. tb detected | 30 | (21) |

| M. tb not detected | 111 | (78) | |

| Contamination | 1 | (1) | |

| Disseminated TB | No | 118 | (83) |

| Yes | 23 | (16) | |

| Not recorded | 1 | (1) | |

| Type of UGTB | Urinary tract TB | 87 | (61) |

| Genital TB | 14 | (10) | |

| Both | 41 | (29) | |

| Previous history of TB | Pulmonary | 6 | (4) |

| Extrapulmonary (except UGTB) | 3 | (2) | |

| None | 131 | (92) | |

| Not recorded | 2 | (1) | |

| BMI at admission | <18.5 | 15 | (11) |

| 18.5–24.9 | 118 | (83) | |

| 25.0–29.9 | 6 | (4) | |

| 30.0–39.9 | 3 | (2) | |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 33 | (23) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 | (8) | |

| Anemia | 33 | (23) | |

| Hepatitis B | 4 | (3) | |

| Hepatitis C | 2 | (1) | |

| HIV status | 3 | (2) | |

| Non-specific urinary tract infection | 63 | (44) | |

| Other 1 | 43 | (30) | |

| Any comorbidity | 90 | (66) | |

| Surgery for UGTB | None | 93 | (65) |

| During intensive phase | 45 | (32) | |

| During continuation phase | 2 | (1) | |

| During both phases | 2 | (1) | |

| Serious adverse events during treatment | Reported | 8 | (6) |

| Not reported | 134 | (94) | |

| Median LOS | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Q1; Q2) | IRR (95% CI) | p | IRR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age groups, years | |||||

| 18–34 | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | ref. | ||

| 35–54 | 56 (56; 57) | 1.05 (0.86; 1.28) | 0.63 | 0.92 (0.77; 1.09) | 0.31 |

| 55–80 | 57 (55; 70) | 0.94 (0.75; 1.18) | 0.56 | 0.93 (0.74; 1.17) | 0.56 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 56 (56; 57) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Female | 56 (56; 58) | 0.95 (0.80; 1.13) | 0.55 | 0.95 (0.82; 1.1) | 0.49 |

| Type of residence | |||||

| Urban | 57 (55; 70) | ref. | - | - | |

| Rural | 56 (56; 57) | 1.00 (0.81; 1.24) | 0.99 | - | - |

| Alcohol abuse at admission | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Yes | 56 (56; 105) | 1.16 (0.67; 2.23) | 0.62 | 2.01 (0.99; 4.21) | 0.06 |

| Current tobacco smoking at admission | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | - | - | |

| Yes | 56 (55; 57) | 0.97 (0.79; 1.20) | 0.78 | - | - |

| Labor migration to other countries in the past 6 months prior to admission | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Yes | 56 (0; 56) | 0.63 (0.43; 0.95) | 0.02 | 0.46 (0.32; 0.69) | <0.001 |

| UGTB diagnosis | |||||

| Clinically diagnosed | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Laboratory confirmed | 56 (55; 59) | 1.08 (0.91; 1.28) | 0.40 | 1.07 (0.92; 1.25) | 0.34 |

| Disseminated TB | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 57) | ref. | - | - | |

| Yes | 56 (55; 76) | 1.00 (0.79; 1.27) | 0.98 | - | - |

| Type of UGTB | |||||

| Urinary tract and genital TB | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | |||

| Urinary tract TB only | 56 (56; 58) | 1.02 (0.84; 1.24) | 0.82 | - | - |

| Genital TB only | 56 (55; 57) | 0.85 (0.63; 1.18) | 0.33 | - | - |

| Previous history of pulmonary or extrapulmonary TB, except UGTB | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 57) | ref. | - | - | |

| Yes | 70 (56; 84) | 1.13 (0.81; 1.65) | 0.49 | - | - |

| BMI | |||||

| <18.5 | 57 (56; 67) | ref. | - | - | |

| 18.5–24.9 | 56 (56; 58) | 1.08 (0.8; 1.41) | 0.61 | - | - |

| >24.9 | 56 (55; 56) | 0.87 (0.57; 1.36) | 0.54 | - | - |

| Hypertension | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Yes | 57 (55; 67) | 1.10 (0.90; 1.36) | 0.34 | 1.12 (0.91; 1.4) | 0.29 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Yes | 55 (54; 57) | 0.86 (0.63; 1.20) | 0.35 | 0.79 (0.57; 1.09) | 0.15 |

| Anemia | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | - | - | |

| Yes | 56 (55; 57) | 0.97 (0.80; 1.20) | 0.80 | - | - |

| Hepatitis B | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 57) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Yes | 125 (85; 248) | 2.80 (1.82; 4.57) | <0.001 | 3.18 (1.98; 5.39) | <0.001 |

| Hepatitis C (ref. no) | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | - | - | |

| Yes | 81 (56; 105) | 1.29 (0.67; 2.92) | 0.49 | - | - |

| HIV status | |||||

| Negative | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Positive | 105 (56; 113) | 1.48 (0.86; 2.82) | 0.19 | 0.53 (0.25; 1.14) | 0.12 |

| Non-specific urinary tract infection | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | - | - | |

| Yes | 56 (55; 58) | 1.02 (0.86; 1.22) | 0.80 | - | - |

| Surgery during treatment | |||||

| No | 56 (55; 57) | ref. | ref. | ||

| Yes | 57 (56; 85) | 1.15 (0.96; 1.37) | 0.14 | 1.18 (1.01; 1.38) | 0.045 |

| Serious adverse events during treatment | |||||

| No | 56 (56; 58) | ref. | - | - | |

| Yes | 56 (55; 71) | 1.02 (0.72; 1.51) | 0.91 | - | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ismatov, B.; Sereda, Y.; Sahakyan, S.; Gadoev, J.; Parpieva, N. Hospitalizations and Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Urogenital Tuberculosis in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2016–2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094817

Ismatov B, Sereda Y, Sahakyan S, Gadoev J, Parpieva N. Hospitalizations and Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Urogenital Tuberculosis in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2016–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094817

Chicago/Turabian StyleIsmatov, Bakhtiyor, Yuliia Sereda, Serine Sahakyan, Jamshid Gadoev, and Nargiza Parpieva. 2021. "Hospitalizations and Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Urogenital Tuberculosis in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2016–2018" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094817

APA StyleIsmatov, B., Sereda, Y., Sahakyan, S., Gadoev, J., & Parpieva, N. (2021). Hospitalizations and Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Urogenital Tuberculosis in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2016–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4817. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094817