Affective Fear of Crime and Its Association with Depressive Feelings and Life Satisfaction in Advanced Age: Cognitive Emotion Regulation as a Moderator?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Fear of Crime in Advanced Age

1.2. Fear of Crime, Depressive Feelings, and Life Satisfaction

1.3. Fear of Crime, Vulnerability, and Cognitive Emotion Regulation

1.4. Current Study

- What are the associations between affective fear of crime and depressive feelings, on the one hand, and life satisfaction, on the other hand, for older adults, while controlling for age and gender?

- 2.

- What is the association between affective fear of crime and adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies in advanced age, while controlling for age and gender?

- 3.

- Do adaptive and maladaptive cognitive emotion regulation strategies moderate the relation between fear of crime and depressive feelings, and fear of crime and satisfaction with life, while controlling for age and gender?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Independent Variable

2.2.2. Dependent Variables

2.2.3. Potentially Moderating Variables

2.3. Covariates

2.3.1. Age

2.3.2. Gender

2.4. Analytic Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Fear of Crime, Depressive Feelings, Life Satisfaction, and Cognitive Emotion Regulation

3.3. Moderating Role of Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies

3.3.1. Depressive Feelings

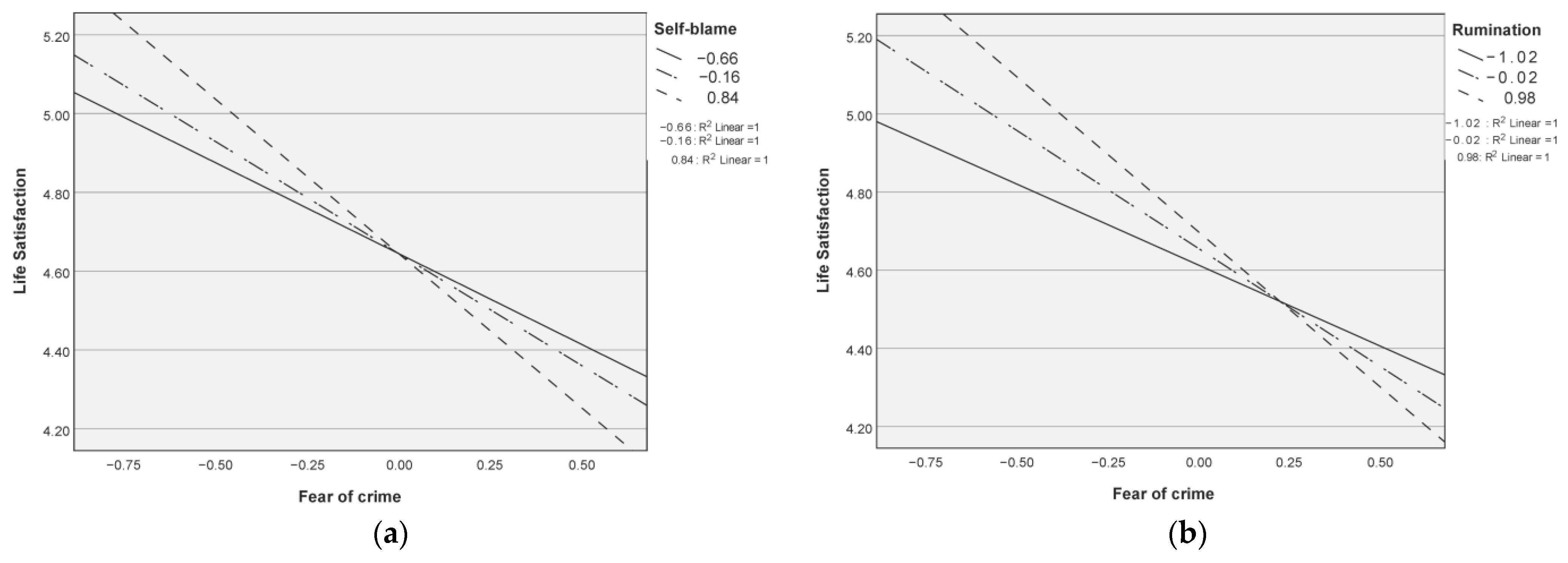

3.3.2. Life Satisfaction

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Beaulieu, M.; Leclerc, N.; Dubé, M. Chapter 8 Fear of Crime Among the Elderly. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2004, 40, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafford, M.; Chandola, T.; Marmot, M. Association Between Fear of Crime and Mental Health and Physical Functioning. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 2076–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Genderson, M.; Pruchno, R. Effects of neighborhood violence and perceptions of neighborhood safety on depressive symptoms of older adults. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 85, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazargan, M. The effects of health, environmental, and socio-psychological variables on fear of crime and its consequences among urban black elderly individuals. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 1994, 38, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, C.E. Fear of Victimization and Health. J. Quant. Criminol. 1993, 9, 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.; Lee, C.; Forjuoh, S.N.; Ory, M.G. Neighborhood safety factors associated with older adults’ health-related outcomes: A systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 165, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesch-Romer, C.; Wahl, H.W. Toward a More Comprehensive Concept of Successful Aging: Disability and Care Needs. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2017, 72, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen, D.; Steverink, N. Kwaliteit van leven. In Handboek Ouderenpsychologie; Vink, M., Kuin, Y., Westerhof, G., Lamers, S., Pot, A.M., Eds.; De Tijdstroom: GH Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal, I.; Lewis, J.; Flynn, T.; Brown, J.; Bond, J.; Coast, J. Developing attributes for a generic quality of life measure for older people: Preferences or capabilities? Soc. Sci. Med. 2006, 62, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Spinhoven, P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001, 30, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire—development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstensen, L.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M.; Charles, S.T. Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. Am. Psychol. 1999, 54, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, H.L.; Gross, J.J. Emotion Regulation in Older Age. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 19, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rühs, F.; Greve, W.; Kappes, C. Coping with criminal victimization and fear of crime: The protective role of accommo-dative self-regulation. Leg. Criminol. Psychol. 2017, 22, 359–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, W. Fear of crime among the elderly: Foresight, not fright. International. Rev. Vict. 1998, 5, 277–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, W.; Leipold, B.; Kappes, C. Fear of Crime in Old Age: A Sample Case of Resilience? J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2018, 73, 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappes, C.; Greve, W.; Hellmers, S. Fear of crime in old age: Precautious behaviour and its relation to situational fear. Eur. J. Ageing 2013, 10, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaGrange, R.L.; Ferraro, K.F. The elderly’s fear of crime: A critical examination of the research. Res. Aging 1987, 9, 372–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.; Gray, E. Functional Fear and Public Insecurities about Crime. Br. J. Criminol. 2009, 50, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.D.; Reyns, B.W.; Kim, D.; Maher, C. Fear of Crime out West: Determinants of Fear of Property and Violent Crime in Five States. Int. J. Offender. Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2020, 64, 1299–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, G.; Ren, L.; He, P. Social disorder and residence-based fear of crime: The differential mediating effects of police effectiveness. J. Crim. Justice 2019, 63, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, M.; Chappell, A.T. Untangling Fear of Crime: A Multi-theoretical Approach to Examining the Causes of Crime-Specific Fear. Sociol. Spectr. 2012, 32, 346–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chataway, M.L.; Hart, T.C. A Social-Psychological Process of “Fear of Crime” for Men and Women: Revisiting Gender Differences from a New Perspective. Vict. Offenders 2019, 14, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acierno, R.; Rheingold, A.A.; Resnick, H.S.; Kilpatrick, D.G. Predictors of fear of crime in older adults. J. Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BRÅ. Brott Mot Äldre. Om Utsatthet Och Otrygghet; Ordförrådet AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccato, V.; Bamzar, R. Elderly Victimization and Fear of Crime in Public Spaces. Int. Crim. Justice Rev. 2016, 26, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heber, A. “The worst thing that could happen”: On altruistic fear of crime. Int. Rev. Vict. 2009, 16, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryce, D.K.; Fuller, K.; Brown, R.A.; VanEaton, T. Examining the Relationship between Citizen Contact with the Community Prosecutor and Fear of Crime. Vict. Offenders 2020, 15, 574–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, C. Fear of crime: A review of the literature. Int. Rev. Vict. 1996, 4, 79–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, P.P. Fear of Crime among the Elderly: Some Issues and Suggestions. Soc. Probl. 1979, 27, 492–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.E.; Marrone, D.F. Scared Sick: Relating Fear of Crime to Mental Health in Older Adults. SAGE Open 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenc, T.; Clayton, S.; Neary, D.; Whitehead, M.; Petticrew, M.; Thomson, H.; Cummins, S.; Sowden, A.; Renton, A. Crime, fear of crime, environment, and mental health and wellbeing: Mapping review of theories and causal pathways. Health Place 2012, 18, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, N.; Lindqvist, K.; Danielsson, I. Fear of crime and psychological and physical abuse associated with ill health in a Swedish population aged 65–84 years. Public Health 2012, 126, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, R.E.; Serpe, R.T. Social integration, fear of crime, and life satisfaction. Sociol. Perspect. 2000, 43, 605–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanslmaier, M. Crime, fear and subjective well-being: How victimization and street crime affect fear and life satisfaction. Eur. J. Criminol. 2013, 10, 515–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazer, D.G. Depression in Late Life: Review and Commentary. J. Gerontol. Med. Sci. 2003, 58, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djernes, J.K. Prevalence and predictors of depression in populations of elderly: A review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006, 113, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; van Vliet, M.; Giezenberg, M.; Winkens, B.; Heerkens, Y.; Dagnelie, P.C.; Knottnerus, J.A. Towards a ’patient-centred’ operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open 2016, 6, 010091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killias, M.; Clerici, C. Different measures of vulnerability in their relation to different dimensions of fear of crime. Br. J. Criminol. 2000, 40, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rader, N.E.; Cossman, J.S.; Porter, J.R. Fear of crime and vulnerability: Using a national sample of Americans to examine two competing paradigms. J. Crim. Justice 2012, 40, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henson, B.; Reyns, B.W. The only thing we have to fear is fear itself and crime: The current state of the fear of crime literature and where it should go next. Sociol. Compass 2015, 9, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killias, M. Vulnerability: Towards a Better Understanding of a Key Variable in the Genesis of Fear of Crime. Violence Vict. 1990, 5, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossman, J.S.; Rader, N.E. Fear of Crime and Personal Vulnerability: Examining Self-Reported Health. Sociol. Spectr. 2011, 31, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J. A psychological perspective on vulnerability in the fear of crime. Psychol. Crime. Law 2009, 15, 365–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadee, D.A.; Virgil, N.J.; Ditton, J. State-trait anxiety and fear of crime. A social psychological perspective. In Fear of Crime. Critical Voices in an Age of Anxiety; Farrall, S.D., Lee, M., Eds.; Routledge-Cavendish: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 168–187. [Google Scholar]

- Lindesay, J. Phobic disorders and fear of crime in the elderly. Aging Ment. Health 1997, 1, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, I.M.E.S.; Domingos, S.P.A.; Cardoso, C.S. Fear of crime, personality and trait emotions: An empirical study. Eur. J. Criminol. 2018, 15, 658–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Ang, S.; Chan, A. Fear of crime is associated with loneliness among older adults in Singapore: Gender and ethnic differences. Health Soc. Care Community 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriel, U.; Greve, W. The psychology of fear of crime. Conceptual and methodological perspectives. Br. J. Criminol. 2003, 43, 600–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, S.T. Emotional Experience and Regulation in Later Life. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging; Schaie, K.W., Willis, S.L., Eds.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 295–310. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1983, 67, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegler, R.; Mitchell, D.B. Aging and fear of crime: An experimental approach to an apparent paradox. Exp. Aging Res. 2003, 29, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.E. Addressing the inconsistencies in fear of crime research: A meta-analytic review. J. Crim. Justice 2016, 47, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfgott, J.B.; Parkin, W.S.; Fisher, C.; Diaz, A. Misdemeanor arrests and community perceptions of fear of crime in Seattle. J. Crim. Justice 2020, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage Publications, Inc: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 6th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: Essex, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis. In A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond, A.S.; Snaith, R.P. The HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; NFER Nelson: Windsor, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrache, C.G.; Rubio, L.; Rubio-Herrera, R. Perceived health status and life satisfaction in old age, and the moderating role of social support. Aging Ment. Health 2017, 21, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.L.; Breetzke, G.D. The Association Between the Fear of Crime, and Mental and Physical Wellbeing in New Zealand. Soc. Indic. Res. 2013, 119, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rypi, A. Not Afraid at All? Dominant and Alternative Interpretative Repertoires in Discourses of the Elderly on Fear of Crime. J. Scand. Stud. Criminol. Crime Prev. 2012, 13, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.; Hooper, P.; Knuiman, M.; Giles-Corti, B. Does heightened fear of crime lead to poorer mental health in new suburbs, or vice versa? Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 168, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koole, S.L. The psychology of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Cogn. Emot. 2009, 23, 4–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Min | Max | M | SD | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affective fear of crime | 1.00 | 4.00 | 1.62 | 0.60 | 554 |

| 2. Depressive feelings | 0.00 | 3.00 | 0.56 | 0.45 | 593 |

| 3. Life satisfaction | 1.00 | 7.00 | 4.66 | 1.28 | 561 |

| 4. Self-blame | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.18 | 0.92 | 578 |

| 5. Rumination | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.53 | 0.97 | 570 |

| 6. Blaming others | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.83 | 0.85 | 577 |

| 7. Catastrophizing | 1.00 | 5.00 | 1.84 | 0.84 | 580 |

| 8. Acceptance | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.28 | 1.09 | 575 |

| 9. Positive refocus | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.55 | 0.98 | 580 |

| 10. Putting into perspective | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.89 | 0.99 | 576 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Affective fear of crime | - | 0.283 ** | −0.284 ** | 0.036 | 0.099 * | 0.126 ** | 0.265 ** | −0.039 | −0.006 | −0.022 |

| 2. Depressive feelings | 0.246 ** | - | −0.545 ** | 0.026 | 0.057 | 0.084 | 0.228 ** | −0.126 ** | −0.180 ** | −0.139 ** |

| 3. Life satisfaction | −0.277 ** | −0.537 ** | - | −0.001 | 0.026 | −0.017 | −0.166 ** | 0.204 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.137 ** |

| 4. Self-blame | 0.027 | 0.033 | −0.003 | - | 0.401 ** | −0.040 | 0.205 ** | 0.337 ** | 0.215 ** | 0.301 ** |

| 5. Rumination | 0.101 * | 0.055 | 0.028 | 0.396 ** | - | 0.141 ** | 0.329 ** | 0.441 ** | 0.250 ** | 0.302 ** |

| 6. Blaming others | 0.099 * | 0.102 * | −0.023 | −0.027 | 0.129 ** | - | 0.346 ** | −0.023 | 0.120 ** | 0.061 |

| 7. Catastrophizing | 0.255 ** | 0.236 ** | −0.160 ** | 0.198 ** | 0.333 ** | 0.322 ** | - | 0.005 | 0.065 | 0.032 |

| 8. Acceptance | −0.032 | −0.125 ** | 0.206 ** | 0.330 ** | 0.444 ** | −0.037 | 0.017 | - | 0.285 ** | 0.372 ** |

| 9. Positive refocus | −0.003 | −0.175 ** | 0.237 ** | 0.212 ** | 0.253 ** | 0.109 * | 0.072 | 0.288 ** | - | 0.447 ** |

| 10. Putting into perspective | −0.020 | −0.133 ** | 0.139 ** | 0.296 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.050 | 0.044 | 0.376 ** | 0.449 ** | - |

| Variable | B | SE | β | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | p | ||||

| Self-blame | ||||||

| Age | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.169 | 0.005 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| Gender 1 | 0.139 | 0.038 | 0.154 | 0.063 | 0.214 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime | 0.195 | 0.031 | 0.266 | 0.134 | 0.257 | <0.001 |

| Self-blame | 0.009 | 0.021 | 0.018 | −0.032 | 0.049 | 0.669 |

| Affective fear of crime × self-blame | −0.013 | 0.034 | −0.016 | −0.080 | 0.053 | 0.700 |

| R2 | 0.107 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.098 | |||||

| Rumination | ||||||

| Age | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.156 | 0.005 | 0.015 | <0.001 |

| Gender 1 | 0.143 | 0.039 | 0.159 | 0.067 | 0.219 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime | 0.201 | 0.032 | 0.275 | 0.138 | 0.264 | <0.001 |

| Rumination | 0.017 | 0.019 | 0.037 | −0.022 | 0.055 | 0.392 |

| Affective fear of crime × rumination | −0.040 | 0.030 | −0.058 | −0.098 | 0.018 | 0.175 |

| R2 | 0.108 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.099 | |||||

| Blaming others | ||||||

| Age | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.170 | 0.005 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| Gender 1 | 0.128 | 0.039 | 0.143 | 0.052 | 0.205 | 0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime | 0.197 | 0.032 | 0.268 | 0.134 | 0.259 | <0.001 |

| Blaming others | 0.043 | 0.022 | 0.083 | −0.001 | 0.086 | 0.055 |

| Affective fear of crime × blaming others | −0.045 | 0.033 | −0.058 | −0.110 | 0.020 | 0.172 |

| R2 | 0.117 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.108 | |||||

| Catastrophizing | ||||||

| Age | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.142 | 0.004 | 0.014 | 0.001 |

| Gender 1 | 0.143 | 0.038 | 0.160 | 0.070 | 0.217 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime | 0.166 | 0.032 | 0.227 | 0.102 | 0.230 | <0.001 |

| Catastrophizing | 0.099 | 0.024 | 0.186 | 0.053 | 0.145 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime × catastrophizing | −0.052 | 0.034 | −0.067 | −0.118 | 0.015 | 0.126 |

| R2 | 0.135 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.126 | |||||

| Acceptance | ||||||

| Age | 0.010 | 0.003 | 0.155 | 0.005 | 0.015 | <0.001 |

| Gender 1 | 0.138 | 0.038 | 0.153 | 0.062 | 0.213 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime | 0.197 | 0.031 | 0.268 | 0.136 | 0.258 | <0.001 |

| Acceptance | −0.041 | 0.017 | −0.099 | −0.075 | −0.007 | 0.019 |

| Affective fear of crime × acceptance | −0.046 | 0.027 | −0.072 | −0.100 | 0.007 | 0.087 |

| R2 | 0.117 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.108 | |||||

| Positive refocus | ||||||

| Age | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.169 | 0.005 | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| Gender 1 | 0.135 | 0.038 | 0.150 | 0.061 | 0.209 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime | 0.191 | 0.031 | 0.261 | 0.130 | 0.251 | <0.001 |

| Positive refocus | −0.081 | 0.019 | −0.182 | −0.119 | −0.044 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime × positive refocus | −0.031 | 0.034 | −0.039 | −0.098 | 0.036 | 0.361 |

| R2 | 0.134 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.126 | |||||

| Putting into perspective | ||||||

| Age | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.182 | 0.006 | 0.017 | <0.001 |

| Gender 1 | 0.137 | 0.038 | 0.153 | 0.062 | 0.211 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime | 0.198 | 0.031 | 0.272 | 0.137 | 0.259 | <0.001 |

| Putting into perspective | −0.052 | 0.019 | −0.118 | −0.089 | −0.016 | 0.005 |

| Affective fear of crime × putting into perspective | −0.010 | 0.031 | −0.014 | −0.071 | 0.051 | 0.747 |

| R2 | 0.126 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.117 | |||||

| Variable | B | SE | β | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | p | ||||

| Self-blame | ||||||

| Age | −0.002 | 0.008 | −0.013 | −0.018 | 0.013 | 0.770 |

| Gender 1 | −0.203 | 0.115 | −0.078 | −0.429 | 0.022 | 0.077 |

| Affective fear of crime | −0.609 | 0.096 | −0.279 | −0.798 | −0.420 | <0.001 |

| Self-blame | 0.005 | 0.061 | 0.004 | −0.115 | 0.126 | 0.933 |

| Affective fear of crime × self-blame | −0.216 | 0.102 | −0.092 | −0.415 | −0.016 | 0.034 |

| R2 | 0.086 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.076 | |||||

| Rumination | ||||||

| Age | −0.004 | 0.008 | −0.020 | −0.019 | 0.012 | 0.638 |

| Gender 1 | −0.187 | 0.114 | −0.072 | −0.411 | 0.036 | 0.101 |

| Affective fear of crime | −0.631 | 0.095 | −0.290 | −0.818 | −0.443 | <0.001 |

| Rumination | 0.046 | 0.058 | 0.034 | −0.068 | 0.161 | 0.429 |

| Affective fear of crime × rumination | −0.190 | 0.091 | −0.090 | −0.370 | −0.011 | 0.038 |

| R2 | 0.091 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.081 | |||||

| Blaming others | ||||||

| Age | −0.003 | 0.008 | −0.017 | −0.019 | 0.013 | 0.691 |

| Gender 1 | −0.199 | 0.117 | −0.076 | −0.429 | 0.032 | 0.091 |

| Affective fear of crime | −0.626 | 0.097 | −0.287 | −0.817 | −0.434 | <0.001 |

| Blaming others | −0.004 | 0.068 | −0.002 | −0.137 | 0.130 | 0.956 |

| Affective fear of crime × blaming others | 0.045 | 0.100 | 0.020 | −0.150 | 0.241 | 0.649 |

| R2 | 0.081 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.071 | |||||

| Catastrophizing | ||||||

| Age | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.004 | −0.015 | 0.017 | 0.926 |

| Gender 1 | −0.203 | 0.113 | −0.078 | −0.426 | 0.020 | 0.074 |

| Affective fear of crime | −0.563 | 0.099 | −0.258 | −0.758 | −0.368 | <0.001 |

| Catastrophizing | −0.216 | 0.071 | −0.140 | −0.355 | −0.077 | 0.002 |

| Affective fear of crime × catastrophizing | 0.116 | 0.109 | 0.048 | −0.098 | 0.330 | 0.287 |

| R2 | 0.098 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.089 | |||||

| Acceptance | ||||||

| Age | −0.005 | 0.008 | −0.026 | −0.020 | 0.011 | 0.536 |

| Gender 1 | −0.165 | 0.112 | −0.063 | −0.386 | 0.055 | 0.142 |

| Affective fear of crime | −0.607 | 0.093 | −0.279 | −0.790 | −0.423 | <0.001 |

| Acceptance | 0.211 | 0.051 | 0.177 | 0.111 | 0.310 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime × acceptance | −0.042 | 0.082 | −0.022 | −0.204 | 0.119 | 0.607 |

| R2 | 0.113 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.104 | |||||

| Positive refocus | ||||||

| Age | −0.003 | 0.008 | −0.018 | −0.019 | 0.012 | 0.665 |

| Gender 1 | −0.180 | 0.111 | −0.069 | −0.399 | 0.039 | 0.107 |

| Affective fear of crime | −0.620 | 0.093 | −0.285 | −0.803 | −0.438 | <0.001 |

| Positive refocus | 0.302 | 0.056 | 0.231 | 0.192 | 0.412 | <0.001 |

| Affective fear of crime × positive refocus | −0.080 | 0.101 | −0.034 | −0.279 | 0.119 | 0.432 |

| R2 | 0.138 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.129 | |||||

| Putting into perspective | ||||||

| Age | −0.005 | 0.008 | −0.028 | −0.021 | 0.010 | 0.517 |

| Gender 1 | −0.165 | 0.113 | −0.063 | −0.387 | 0.057 | 0.145 |

| Affective fear of crime | −0.614 | 0.094 | −0.284 | −0.799 | −0.429 | <0.001 |

| Putting into perspective | 0.163 | 0.056 | 0.126 | 0.053 | 0.273 | 0.004 |

| Affective fear of crime × putting into perspective | −0.044 | 0.093 | −0.021 | −0.228 | 0.139 | 0.635 |

| R2 | 0.097 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.088 | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golovchanova, N.; Boersma, K.; Andershed, H.; Hellfeldt, K. Affective Fear of Crime and Its Association with Depressive Feelings and Life Satisfaction in Advanced Age: Cognitive Emotion Regulation as a Moderator? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094727

Golovchanova N, Boersma K, Andershed H, Hellfeldt K. Affective Fear of Crime and Its Association with Depressive Feelings and Life Satisfaction in Advanced Age: Cognitive Emotion Regulation as a Moderator? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094727

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolovchanova, Nadezhda, Katja Boersma, Henrik Andershed, and Karin Hellfeldt. 2021. "Affective Fear of Crime and Its Association with Depressive Feelings and Life Satisfaction in Advanced Age: Cognitive Emotion Regulation as a Moderator?" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094727

APA StyleGolovchanova, N., Boersma, K., Andershed, H., & Hellfeldt, K. (2021). Affective Fear of Crime and Its Association with Depressive Feelings and Life Satisfaction in Advanced Age: Cognitive Emotion Regulation as a Moderator? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4727. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094727