Role of Callous and Unemotional (CU) Traits on the Development of Youth with Behavioral Disorders: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. CU Traits Assessment

1.2. Etiology

1.2.1. Genetic Risk Factors

1.2.2. Emotional and Cognitive Risk Factors

1.2.3. Neurobiological Factors

1.2.4. Environmental Risk Factors

1.3. Development

1.4. Intervention

1.5. Research Aims and Questions

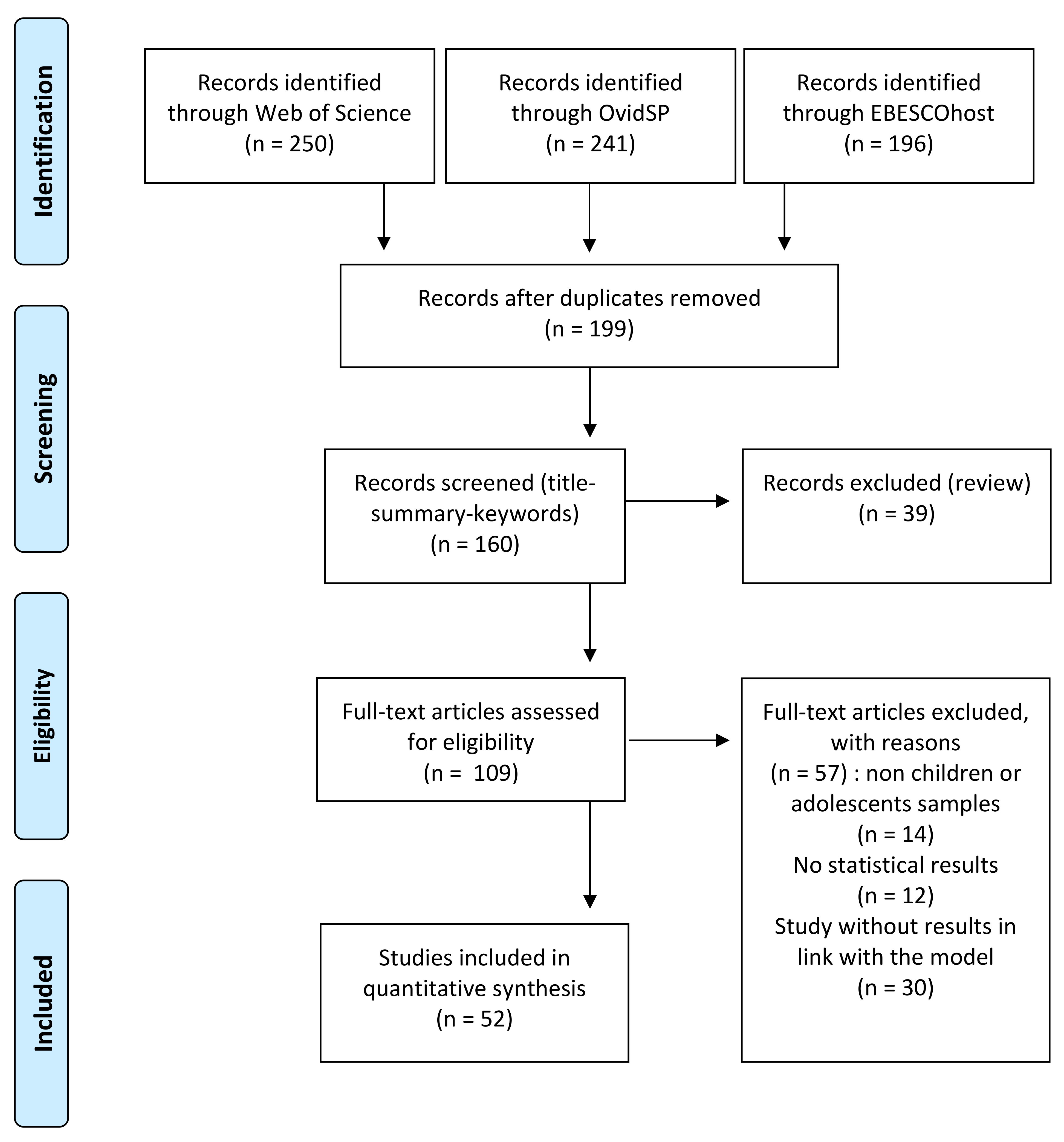

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.2. Studies Design and Key Methods

3.3. Mental Health

3.4. Neurobiological Markers and CU Traits (Physical Health)

3.5. Context

3.6. Social Adjustment

3.7. Social Interactions and Social Roles

3.8. Cognition

4. Discussion

4.1. Characteristics of Samples

4.2. Measure of CU Traits

4.3. Mental Health Dimension

4.4. Neurophysiological Health

4.5. Context

4.6. Cognition

4.7. Social Interactions (and Social Roles)

4.8. Social Adjustment

4.9. Implications for Practice

4.10. Strengths and Limitations

4.11. Further Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Arlington, VA, USA, 2013; ISBN 0-89042-555-8.

- Frick, P.J. Developmental Pathways to Conduct Disorder: Implications for Future Directions in Research, Assessment, and Treatment. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2012, 41, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piquero, A.R.; Shepherd, I.; Shepherd, J.P.; Farrington, D.P. Impact of offending trajectories on health: Disability, hospitalisation and death in middle-aged men in the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2011, 21, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baroncelli, A.; Ciucci, E. Bidirectional Effects Between Callous-Unemotional Traits and Student-Teacher Relationship Quality Among Middle School Students. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2020, 48, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waschbusch, D.A.; Walsh, T.M.; Andrade, B.F.; King, S.; Carrey, N.J. Social problem solving, conduct problems, and callous-unemotional traits in children. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2007, 37, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, P.J.; Ray, J.V. Evaluating Callous-Unemotional Traits as a Personality Construct. J. Pers. 2015, 83, 710–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, E.; Chhoa, C.Y.; Midouhas, E.; Allen, J.L. Callous-Unemotional Traits and Academic Performance in Secondary School Students: Examining the Moderating Effect of Gender. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciucci, E.; Baroncelli, A. Emotion-Related Personality Traits and Peer Social Standing: Unique and Interactive Effects in Cyberbullying Behaviors. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2014, 17, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, J.H.L.; Barry, C.T.; Sergiou, C.S. Interventions for Improving Affective Abilities in Adolescents: An Integrative Review Across Community and Clinical Samples of Adolescents. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2017, 2, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; White, S.F. Research Review: The importance of callous-unemotional traits for developmental models of aggressive and antisocial behavior. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2008, 49, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; Stickle, T.R.; Dandreaux, D.M.; Farrell, J.M.; Kimonis, E.R. Callous-unemotional traits in predicting the severity and stability of conduct problems and delinquency. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2005, 33, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; Kimonis, E.R.; Dandreaux, D.M.; Farell, J.M. The 4 Year Stability of Psychopathic Traits in Non-Referred Youth. Behav. Sci. Law 2003, 21, 713–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Rouchy, E.; Michel, G. The role of Callous-Unemotional traits in delinquent and criminal trajectories: A review of longitudinal studies. Ann. Med. Psychol. 2019, 177, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J. The Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Trait; Multi-Health System: Toronto, Canada, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cardinale, E.M.; Marsh, A.A. The Reliability and Validity of the Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits: A Meta-Analytic Review. Assessment 2020, 27, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimonis, E.R.; Frick, P.J.; Skeem, J.L.; Marsee, M.A.; Cruise, K.; Munoz, L.C.; Aucoin, K.J.; Morris, A.S. Assessing callous–unemotional traits in adolescent offenders: Validation of the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 2008, 31, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essau, C.A.; Sasagawa, S.; Frick, P.J. Callous-unemotional traits in a community sample of adolescents. Assessment 2006, 13, 454–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciucci, E.; Baroncelli, A.; Franchi, M.; Golmaryami, F.N.; Frick, P.J. The association between callous-unemotional traits and behavioral and academic adjustment in children: Further validation of the inventory of callous-unemotional traits. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2014, 36, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roose, A.; Bijttebier, P.; Decoene, S.; Claes, L.; Frick, P.J. Assessing the affective features of psychopathy in adolescence: A further validation of the inventory of callous and unemotional traits. Assessment 2010, 17, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechorro, P.; Ray, J.V.; Barroso, R.; Maroco, J.; Gonçalves, R.A. Validation of the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits Among a Portuguese Sample of Detained Juvenile Offenders. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2016, 60, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, L.; Granero, R.; de la Osa, N.; Domènech, J.M. Developmental trajectories of callous-unemotional traits, anxiety and oppositionality in 3–7 year-old children in the general population. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2017, 111, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications and Programming; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 9781138797031. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, J.V.; Frick, P.J. Assessing Callous-Unemotional Traits Using the Total Score from the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2020, 49, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; Ray, J.V.; Thornton, L.C.; Kahn, R.E. Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbach, R.; Berryessa, C.M.; Raine, A. Brain imaging research on psychopathy: Implications for punishment, prediction, and treatment in youth and adults. J. Crim. Justice 2015, 43, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viding, E.; McCrory, E.J. Understanding the development of psychopathy: Progress and challenges. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrì, S.; Zoratto, F.; Chiarotti, F.; Laviola, G. Can laboratory animals violate behavioural norms? Towards a preclinical model of conduct disorder. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 91, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reidy, D.E.; Krusemark, E.; Kosson, D.S.; Kearns, M.C.; Smith-Darden, J.; Kiehl, K.A. The Development of Severe and Chronic Violence Among Youth: The Role of Psychopathic Traits and Reward Processing. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 967–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, R.; Hyde, L.W. Callous–Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood: Measurement, Meaning, and the Influence of Parenting. Child Dev. Perspect. 2017, 11, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, A.A.; Blair, R.J.; Hettema, J.M.; Roberson-Nay, R. The genetic underpinnings of callous-unemotional traits: A systematic research review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 100, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salekin, R.T. Research Review: What do we know about psychopathic traits in children? J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2017, 58, 1180–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Hyde, L.W. Callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood: The development of empathy and prosociality gone awry. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2018, 20, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.H.; Clanton, R.L.; Rogers, J.C.; De Brito, S.A. Neuroimaging findings in disruptive behavior disorders. CNS Spectr. 2015, 20, 369–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Raine, A. The neuroscience of psychopathy and forensic implications. Psychol. Crime Law 2018, 24, 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herpers, P.C.M.; Scheepers, F.E.; Bons, D.M.A.; Buitelaar, J.K.; Rommelse, N.N.J. The cognitive and neural correlates of psychopathy and especially callous-unemotional traits in youths: A systematic review of the evidence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2014, 26, 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Hyde, L.W.; Klump, K.L.; Burt, S.A. Parenting Is an Environmental Predictor of Callous-Unemotional Traits and Aggression: A Monozygotic Twin Differences Study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Gardner, F.; Hyde, L.W. What are the associations between parenting, callous–unemotional traits, and antisocial behavior in youth? A systematic review of evidence. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyde, L.W.; Waller, R.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Shaw, D.S.; Neiderhiser, J.M.; Ganiban, J.M.; Reiss, D.; Leve, L.D. Heritable and nonheritable pathways to early callous-unemotional behaviors. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Trentacosta, C.J.; Shaw, D.S.; Neiderhiser, J.M.; Ganiban, J.M.; Reiss, D.; Leve, L.D.; Hyde, L.W. Heritable temperament pathways to early callous-unemotional behaviour. Br. J. Psychiatry 2016, 209, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kam, C.-M.; Greenberg, M.T.; Walls, C.T. Examining the role of implementation quality in school-based. Prev. Sci. 2003, 4, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, P.A.; Landis, T.; Maharaj, A.; Ros-Demarize, R.; Hart, K.C.; Garcia, A. Differentiating Preschool Children with Conduct Problems and Callous-Unemotional Behaviors through Emotion Regulation and Executive Functioning. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, A.; Harries, T.; Moulds, L.; Miller, P. Addressing child-to-parent violence: Developmental and intervention considerations. J. Fam. Stud. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuay, H.S.; Tiffin, P.A.; Boothroyd, L.G.; Towl, G.J.; Centifanti, L.C.M. A New Trait-Based Model of Child-to-Parent Aggression. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2017, 2, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.W.; Hsiao, R.C.; Chen, L.M.; Sung, Y.H.; Hu, H.F.; Yen, C.F. Associations between callous-unemotional traits and various types of involvement in school bullying among adolescents in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2019, 118, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, I.; Ttofi, M.M.; Farrington, D.P. Empathy and Callous–Unemotional Traits in Different Bullying Roles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerr, M.; Van Zalk, M.; Stattin, H. Psychopathic traits moderate peer influence on adolescent delinquency. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2012, 53, 826–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallion, J.S.; Wood, J.L. Emotional processes and gang membership: A narrative review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 43, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, K.A. Understanding heterogeneity in conduct disorder: A review of psychophysiological studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 91, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, R.J.R. Dysfunctional neurocognition in individuals with clinically significant psychopathic traits. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 21, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waschbusch, D.A.; Willoughy, M.T. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and callous-unemotional traits as moderators of conduct problems when examining impairment and aggression in elementary school children. Agress. Behav. 2008, 34, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisano, S.; Muratori, P.; Gorga, C.; Levantini, V.; Iuliano, R.; Catone, G.; Coppola, G.; Milone, A.; Masi, G. Conduct disorders and psychopathy in children and adolescents: Aetiology, clinical presentation and treatment strategies of callous-unemotional traits. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2017, 43, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willoughby, M.T.; Mills-Koonce, W.R.; Gottfredson, N.C.; Wagner, N.J. Measuring callous unemotional behaviors in early childhood: Factor structure and the prediction of stable aggression in middle childhood. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2014, 36, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P.J.; Ray, J.V.; Thornton, L.C.; Kahn, R.E. Annual research review: A developmental psychopathology approach to understanding callous-unemotional traits in children and adolescents with serious conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2014, 55, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, R.; Dishion, T.J.; Shaw, D.S.; Gardner, F.; Wilson, M.N.; Hyde, L.W. Does early childhood callous-unemotional behavior uniquely predict behavior problems or callous-unemotional behavior in late childhood? Dev. Psychol. 2016, 52, 1805–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, J.D.; Waldman, I.; Lahey, B.B. predictive validity of childhood oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: Implications for the DSM-V. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2010, 119, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, S.; Waller, R.; Viding, E. Practitioner Review: Involving young people with callous unemotional traits in treatment-does it work? A systematic review. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2016, 57, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawes, D.J.; Price, M.J.; Dadds, M.R. Callous-Unemotional Traits and the Treatment of Conduct Problems in Childhood and Adolescence: A Comprehensive Review. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 17, 248–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadds, M.R.; Cauchi, A.J.; Wimalaweera, S.; Hawes, D.J.; Brennan, J. Outcomes, moderators, and mediators of empathic-emotion recognition training for complex conduct problems in childhood. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 199, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masi, G.; Milone, A.; Manfredi, A.; Brovedani, P.; Pisano, S.; Muratori, P. Combined pharmacotherapy-multimodal psychotherapy in children with Disruptive Behavior Disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 238, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, L.D.; Raine, A. Psychopathy: An Introduction to Biological Findings and Their Implications; NYU Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag, L.S.; Perlman, S.B.; Blair, R.J.; Leibenluft, E.; Briggs-Gowan, M.J.; Pine, D.S. The neurodevelopmental basis of early childhood disruptive behavior: Irritable and callous phenotypes as exemplars. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 114–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajos, J.M.; Beaver, K.M. The effect of omega-3 fatty acids on aggression: A meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 69, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hanlon, A.; Ma, C.; Zhao, S.R.; Cao, S.; Compher, C. Low Blood Zinc, Iron, and Other Sociodemographic Factors Associated with Behavior Problems in Preschoolers. Nutrients 2014, 6, 530–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, A.L.; Raine, A. Neurocriminology: Implications for the punishment, prediction and prevention of criminal behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reidy, D.E.; Kearns, M.C.; Degue, S. Reducing psychopathic violence: A review of the treatment literature. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2013, 18, 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colins, O.F.; Van Damme, L.; Hendriks, A.M.; Georgiou, G. The DSM-5 with Limited Prosocial Emotions Specifier for Conduct Disorder: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2020, 42, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanska, G.; Boldt, L.J.; Kim, S.; Yoon, J.E.; Philibert, R.A.; Bell, G.R.; Crothers, L.M.; Hughes, T.L.; Kanyongo, G.Y.; Kolbert, J.B.; et al. What can we learn about emotion by studying psychopathy? J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2016, 47, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalock, R.L.; Keith, K.D.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Gómez, L.E. Quality of Life Model Development and Use in the Field of Intellectual Disability. Underst. Investig. Response Process. Valid. Res. 2010, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghajani, M.; Klapwijk, E.T.; van der Wee, N.J.; Veer, I.M.; Rombouts, S.A.R.B.; Boon, A.E.; van Beelen, P.; Popma, A.; Vermeiren, R.R.J.M.; Colins, O.F. Disorganized Amygdala Networks in Conduct-Disordered Juvenile Offenders with Callous-Unemotional Traits. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 82, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crum, K.I.; Waschbusch, D.A.; Willoughby, M.T. Callous-Unemotional Traits, Behavior Disorders, and the Student–Teacher Relationship in Elementary School Students. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2016, 24, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezpeleta, L.; Navarro, J.B.; de la Osa, N.; Penelo, E.; Trepat, E.; Martin, V.; Domènech, J.M. Attention to emotion through a go/no-go task in children with oppositionality and callous–unemotional traits. Compr. Psychiatry 2017, 75, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, G.S.; Benga, O.; Marină, C. Attentional orientation patterns toward emotional faces and temperamental correlates of preschool oppositional defiant problems: The moderating role of callous-unemotional traits and anxiety symptoms. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grazioplene, R.; Tseng, W.L.; Cimino, K.; Kalvin, C.; Ibrahim, K.; Pelphrey, K.A.; Sukhodolsky, D.G. Fixel-Based Diffusion Magnetic Resonance Imaging Reveals Novel Associations Between White Matter Microstructure and Childhood Aggressive Behavior. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimag. 2020, 5, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raschle, N.M.; Menks, W.M.; Fehlbaum, L.V.; Steppan, M.; Smaragdi, A.; Gonzalez-Madruga, K.; Rogers, J.; Clanton, R.; Kohls, G.; Martinelli, A.; et al. Callous-unemotional traits and brain structure: Sex-specific effects in anterior insula of typically-developing youths. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 17, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker-Huvenaars, M.J.; Greven, C.U.; Herpers, P.; Wiegers, E.; Jansen, A.; van der Steen, R.; van Herwaarden, A.E.; Baanders, A.N.; Nijhof, K.S.; Scheepers, F.; et al. Saliva oxytocin, cortisol, and testosterone levels in adolescent boys with autism spectrum disorder, oppositional defiant disorder/conduct disorder and typically developing individuals. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 30, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, T.D.; Frick, P.J.; Fanti, K.A.; Kimonis, E.R.; Lordos, A. Factors differentiating callous-unemotional children with and without conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2016, 57, 976–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, N.D.; Gillespie, S.M.; Centifanti, L.C.M. Callous-unemotional traits and fearlessness: A cardiovascular psychophysiological perspective in two adolescent samples using virtual reality. Dev. Psychopathol. 2020, 32, 803–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winstanley, M.; Webb, R.T.; Conti-Ramsden, G. Developmental language disorders and risk of recidivism among young offenders. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, T.; Apter, A.; Djalovski, A.; Peskin, M.; Fennig, S.; Gat-Yablonski, G.; Bar-Maisels, M.; Borodkin, K.; Bloch, Y. The reliability, concurrent validity and association with salivary oxytocin of the self-report version of the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits in adolescents with conduct disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2017, 256, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitti, S.A.; Sullivan, T.N.; McDonald, S.E.; Farrell, A.D. Longitudinal relations between beliefs supporting aggression and externalizing outcomes: Indirect effects of anger dysregulation and callous-unemotional traits. Aggress. Behav. 2019, 45, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethi, A.; O’Nions, E.; McCrory, E.; Bird, G.; Viding, E. An fMRI investigation of empathic processing in boys with conduct problems and varying levels of callous-unemotional traits. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 18, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.C.; Gonzalez-Madruga, K.; Kohls, G.; Baker, R.H.; Clanton, R.L.; Pauli, R.; Birch, P.; Chowdhury, A.I.; Kirchner, M.; Andersson, J.L.R.; et al. White Matter Microstructure in Youths With Conduct Disorder: Effects of Sex and Variation in Callous Traits. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2019, 58, 1184–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeden, A.L.; Cardinale, E.M.; Lozier, L.M.; VanMeter, J.W.; Marsh, A.A. Callous-unemotional traits drive reduced white-matter integrity in youths with conduct problems. Psychol. Med. 2015, 45, 3033–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, S.E.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y. Social Adversity and Antisocial Behavior: Mediating Effects of Autonomic Nervous System Activity. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2017, 45, 1553–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizeq, J.; Toplak, M.E.; Ledochowski, J.; Basile, A.; Andrade, B.F. Callous-Unemotional Traits and Executive Functions are Unique Correlates of Disruptive Behavior in Children. Dev. Neuropsychol. 2020, 45, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Madruga, K.; Rogers, J.; Toschi, N.; Riccelli, R.; Smaragdi, A.; Puzzo, I.; Clanton, R.; Andersson, J.; Baumann, S.; Kohls, G.; et al. White matter microstructure of the extended limbic system in male and female youth with conduct disorder. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimonis, E.R.; Fleming, G.; Briggs, N.; Brouwer-French, L.; Frick, P.J.; Hawes, D.J.; Bagner, D.M.; Thomas, R.; Dadds, M. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy Adapted for Preschoolers with Callous-Unemotional Traits: An Open Trial Pilot Study. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2019, 48, S347–S361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, Y.; Pease, C.R.; Pingault, J.; Viding, E. Genetic and environmental influences on the developmental trajectory of callous-unemotional traits from childhood to adolescence. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2021, 62, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frick, P.J.; Hare, R.D. Antisocial Process Screening Device (APSD): Technical Manual; MHS: North Tonawanda, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Andershed, H.; Hodgins, S.; Tengström, A. Convergent validity of the youth psychopathic traits inventory (YPI): Association with the psychopathy checklist: Youth version (PCL:YV). Assessment 2007, 14, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynam, D.R. Early identification of chronic offenders: Who is the fledgling psychopath? Psychol. Bull. 1996, 120, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, T.M.; Leslie, A. Rescorla Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles; University of Vermont: Burlington, VT, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch, D.A.; Porter, S.; Carrey, N.; Kazmi, S.O.; Roach, K.A.; D’Amico, D.A. Investigation of the heterogeneity of disruptive behaviour in elementary-age children. Can. J. Behav. Sci. 2004, 36, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotzinger, O.; Grotzinger, A.D.; Mann, F.D.; Patterson, M.W. Corrigendum to: Hair and Salivary Testosterone, Hair Cortisol, and Externalizing Behaviors in Adolescents (Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 688–699, 10.1177/0956797617742981). Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J.; Birmaher, B.; Brent, D.; Rao, U.; Flynn, C.; Moreci, P.; Williamson, D.; Ryan, N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1997, 36, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, G.; Pisano, S.; Brovedani, P.; Maccaferri, G.; Manfredi, A.; Milone, A.; Nocentini, A.; Polidori, L.; Ruglioni, L.; Muratori, P. Trajectories of callous–unemotional traits from childhood to adolescence in referred youth with a disruptive behavior disorder who received intensive multimodal therapy in childhood. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2018, 14, 2287–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.J.; Ou, J.J.; Gong, J.B.; Wang, S.H.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Zhu, F.R.; Liu, X.D.; Zhao, J.P.; Luo, X.R.; Petalas, M.A.; et al. To print this document, select the Print. Heal. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 3, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Dodge, K.; Loeber, R.; Gatzke-Kopp, L.; Lynam, D.; Reynolds, C.; Stouthamer-Loeber, M.; Liu, J. The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggress. Behav. 2006, 32, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, M.C.; Mulder, L.M.; Zwiers, M.P.; Sethi, A.; Hoekstra, P.J.; Dietrich, A.; Baumeister, S.; Aggensteiner, P.M.; Banaschewski, T.; Brandeis, D.; et al. Distinct associations between fronto-striatal glutamate concentrations and callous-unemotional traits and proactive aggression in disruptive behavior. Cortex 2019, 121, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino, J.N.; Gruber, C.P. Social Responsiveness Scale; Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou, G.; Demetriou, C.A.; Fanti, K.A. Distinct Empathy Profiles in Callous Unemotional and Autistic Traits: Investigating Unique and Interactive Associations with Affective and Cognitive Empathy. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2019, 47, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, M.; Bailey, A.; Lord, C.; Berument, S.K. Social Communication Questionnaire; Western Psychological Services: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, D.D.M. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Adolescents, and Parents (DISCAP); Griffith University: Brisbane, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford, R.; Gliga, T.; Hendry, A.; Jones, E.J.H.; Pasco, G.; Charman, T.; Johnson, M.H.; Pickles, A.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Bolton, P.; et al. Infant regulatory function acts as a protective factor for later traits of autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder but not callous unemotional traits. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2019, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dackis, M.N.; Rogosch, F.A.; Cicchetti, D. Child maltreatment, callous-unemotional traits, and defensive responding in high-risk children: An investigation of emotion-modulated startle response. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 1527–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elizur, Y.; Somech, L.Y.; Vinokur, A.D. Effects of Parent Training on Callous-Unemotional Traits, Effortful Control, and Conduct Problems: Mediation by Parenting. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2017, 45, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, R.M.L.; Adams, W.J.; Garner, M.; Sonuga-Barke, E.J.S.; Fairchild, G. Attentional Biases to Emotional Faces in Adolescents with Conduct Disorder, Anxiety Disorders, and Comorbid Conduct and Anxiety Disorders. J. Exp. Psychopathol. 2016, 7, 466–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, S.E.; Dmitrieva, J.; Shin, S.; Hitti, S.A.; Graham-Bermann, S.A.; Ascione, F.R.; Williams, J.H. The role of callous/unemotional traits in mediating the association between animal abuse exposure and behavior problems among children exposed to intimate partner violence. Child Abus. Negl. 2017, 72, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanti, K.A.; Andershed, H.; Colins, O.F.; Sikki, M. Stability and change in callous-unemotional traits: Longitudinal associations with potential individual and contextual risk and protective factors. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2017, 87, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kearney, R.; Salmon, K.; Liwag, M.; Fortune, C.A.; Dawel, A. Emotional Abilities in Children with Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD): Impairments in Perspective-Taking and Understanding Mixed Emotions are Associated with High Callous–Unemotional Traits. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2017, 48, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozley, M.M.; Lin, B.; Kerig, P.K. Posttraumatic Overmodulation, Callous–Unemotional Traits, and Offending Among Justice-Involved Youth. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2018, 27, 744–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.F.; Van Tieghem, M.; Brislin, S.J.; Sypher, I.; Sinclair, S.; Pine, D.S.; Hwang, S.; Blair, R.J.R. Neural correlates of the propensity for retaliatory behavior in youths with disruptive behavior disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, R.; Gardner, F.; Shaw, D.S.; Dishion, T.J.; Wilson, M.N.; Hyde, L.W. Callous-Unemotional Behavior and Early-Childhood Onset of Behavior Problems: The Role of Parental Harshness and Warmth. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2015, 44, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Salmon, C.; Côté, S.; Fourneret, P.; Gasquet, I.; Guedeney, A.; Hamon, M.; Lamboy, B.; Le Heuzey, M.-F.; Michel, G.; Jean-Philippe, R.; et al. Troubles des Conduites Chez L’enfant et L’adolescent Charles. Ph.D. Thesis, Institut National De la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska, G.; Barry, R.A.; Stellern, S.A.; Bleness, J.J.O. Early Attachment Organization Moderates the Parent—Child Mutually Coercive Pathway to Children ’ s Antisocial Conduct. Child Dev. 2009, 80, 1288–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muratori, P.; Lochman, J.E.; Lai, E.; Milone, A.; Nocentini, A.; Pisano, S.; Righini, E.; Masi, G. Which dimension of parenting predicts the change of callous unemotional traits in children with disruptive behavior disorder? Compr. Psychiatry 2016, 69, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedford, R.; Wagner, N.J.; Rehder, P.D.; Propper, C.; Willoughby, M.T.; Mills-Koonce, R.W. The role of infants’ mother-directed gaze, maternal sensitivity, and emotion recognition in childhood callous unemotional behaviours. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2017, 26, 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.; Graña, J.L.; González-Cieza, L. Self-reported physical and emotional abuse among youth offenders and their association with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology: A preliminary study. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2014, 58, 590–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horan, J.M.; Brown, J.L.; Jones, S.M.; Aber, J.L. The Influence of Conduct Problems and Callous-Unemotional Traits on Academic Development Among Youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 1245–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanska, G.; Boldt, L.J.; Kim, S.; Yoon, J.E.; Philibert, R.A. Developmental interplay between children’s biobehavioral risk and the parenting environment from toddler to early school age: Prediction of socialization outcomes in preadolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meffert, H.; Thornton, L.C.; Tyler, P.M.; Botkin, M.L.; Erway, A.K.; Kolli, V.; Pope, K.; White, S.F.; Blair, R.J.R. Moderation of prior exposure to trauma on the inverse relationship between callous-unemotional traits and amygdala responses to fearful expressions: An exploratory study. Psychol. Med. 2018, 48, 2530–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raschle, N.M.; Menks, W.M.; Fehlbaum, L.V.; Tshomba, E.; Stadler, C. Structural and Functional Alterations in Right Dorsomedial Prefrontal and Left Insular Cortex Co-Localize in Adolescents with Aggressive Behaviour: An ALE Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roslyne Wilkinson, H.; Jones Bartoli, A. Antisocial behaviour and teacher–student relationship quality: The role of emotion-related abilities and callous–unemotional traits. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2021, 91, 482–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronald Bell, G.; Crothers, L.M.; Hughes, T.L.; Kanyongo, G.Y.; Kolbert, J.B.; Parys, K. Callous-unemotional traits, relational and social aggression, and interpersonal maturity in a sample of behaviorally disordered adolescents. J. Appl. Sch. Psychol. 2018, 34, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S.F.; Cruise, K.R.; Frick, P.J. Differential correlates to self-report and parent-report of callous-unemotional traits in a sample of juvenile sexual offenders. Behav. Sci. Law 2009, 27, 910–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Lilienfeld, S.O.; Reddy, S.D.; Latzman, R.D.; Roose, A.; Craighead, L.W.; Pace, T.W.W.; Raison, C.L. The Inventory of Callous and Unemotional Traits. Assessment 2013, 20, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forth, A.E.; Kosson, D.S.; Hare, R.D. The Hare Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version; Multi-Health System: Toronto, Canada, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, P.J. Clinical Assessment of Prosocial Emotions (Cape); Unpublished Test Manual; University of New Orleans: New Orelans, LA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Colins, O.F.; Andershed, H.; Frogner, L.; Lopez-Romero, L.; Veen, V.; Andershed, A.-K. A New Measure to Assess Psychopathic Personality in Children: The Child Problematic Traits Inventory. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2014, 36, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, M.; Rouchy, E.; Michel, G. Les traits pré-psychopathiques chez l’enfant et l’adolescent: Aspects développementaux, structuraux et étiopathogéniques. Neuropsychiatr. Enfance. Adolesc. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andershed, H.; Colins, O.F.; Salekin, R.T.; Lordos, A.; Kyranides, M.N.; Fanti, K.A. Callous-Unemotional Traits Only Versus the Multidimensional Psychopathy Construct as Predictors of Various Antisocial Outcomes During Early Adolescence. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2018, 40, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanti, K.A.; Frick, P.J.; Georgiou, S. Linking callous-unemotional traits to instrumental and non-instrumental forms of aggression. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 2009, 31, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Raine, A.; Venables, P.H.; Dawson, M.E.; Mednick, S.A. Association of Poor Childhood Fear Conditioning and Adult Crime. Am. J. Psychiatry 2010, 167, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine, A. Antisocial Personality as a Neurodevelopmental Disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2018, 14, 259–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, A.A. What can we learn about emotion by studying psychopathy? Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blair, R.J.R. Facial expressions, their communicatory functions and neuro–cognitive substrates. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2003, 358, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzzo, I.; Seunarine, K.; Sully, K.; Darekar, A.; Clark, C.; Sonuga-Barke, E.J.S.; Fairchild, G. Altered White-Matter Microstructure in Conduct Disorder Is Specifically Associated with Elevated Callous-Unemotional Traits. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2018, 46, 1451–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, K.; Kimonis, E.R. Parent-child interaction therapy for the treatment of Asperger’s disorder in early childhood: A case study. Clin. Case Stud. 2013, 12, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foulkes, L.; Mccrory, E.J.; Neumann, C.S.; Viding, E. Inverted Social Reward: Associations between Psychopathic Traits and Self-Report and Experimental Measures of Social Reward. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 106000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Cauffman, E.; Miller, J.D.; Mulvey, E. Investigating Different Factor Structures of the Psychopathy Checklist: Youth Version: Confirmatory Factor Analytic Findings. Psychol. Assess. 2006, 18, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longman, T.; Hawes, D.J.; Kohlhoff, J. Callous–Unemotional Traits as Markers for Conduct Problem Severity in Early Childhood: A Meta-analysis. Child Psychiatry Hum. Dev. 2016, 47, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine, A.; Portnoy, J.; Liu, J.; Mahoomed, T.; Hibbeln, J.R. Reduction in behavior problems with omega-3 supplementation in children aged 8-16 years: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, stratified, parallel-group trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2015, 56, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R.; Hyde, L.W.; Baskin-Sommers, A.R.; Olson, S.L. Interactions between Callous Unemotional Behaviors and Executive Function in Early Childhood Predict later Aggression and Lower Peer-liking in Late-childhood. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2017, 45, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Carmona, M.; Marín, M.D.; Aguayo, R. Burnout syndrome in secondary school teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2019, 22, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahey, B.B. What we need to know about callous-unemotional traits: Comment on frick, ray, thornton, and kahn (2014). Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkaki, I.; Cima, M.; Granic, I. The role of trauma in the hormonal interplay of cortisol, testosterone, and oxytocin in adolescent aggression. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 88, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fairchild, G.; Hawes, D.J.; Frick, P.J.; Copeland, W.E.; Odgers, C.L.; Franke, B.; Freitag, C.M.; De Brito, S.A. Conduct disorder. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.L.; Bird, E.; Chhoa, C.Y. Bad Boys and Mean Girls: Callous-Unemotional Traits, Management of Disruptive Behavior in School, the Teacher-Student Relationship and Academic Motivation. Front. Educ. 2018, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, N.M.G.; Rijsdijk, F.V.; McCrory, E.J.P.; Viding, E. Etiology of Different Developmental Trajectories of Callous-Unemotional Traits. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2010, 49, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Squillaci, M.; Benoit, V. Role of Callous and Unemotional (CU) Traits on the Development of Youth with Behavioral Disorders: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094712

Squillaci M, Benoit V. Role of Callous and Unemotional (CU) Traits on the Development of Youth with Behavioral Disorders: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094712

Chicago/Turabian StyleSquillaci, Myriam, and Valérie Benoit. 2021. "Role of Callous and Unemotional (CU) Traits on the Development of Youth with Behavioral Disorders: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094712

APA StyleSquillaci, M., & Benoit, V. (2021). Role of Callous and Unemotional (CU) Traits on the Development of Youth with Behavioral Disorders: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4712. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094712