The Effectiveness of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness Group Intervention for Enhancing the Psychological and Physical Well-Being of Adults with Overweight or Obesity Seeking Treatment: The Mind&Life Randomized Control Trial Study Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design and Setting

2.2. Patient Involvement

2.3. Participants

2.3.1. Recruitment

2.3.2. Sample

Eligibility Criteria

Sample Size

2.4. Interventions

2.4.1. Treatment as Usual

2.4.2. Mind&Life Intervention

2.4.3. Concomitant Interventions

2.5. Randomization

2.6. Plan to Promote Participant Adherence or Retention

2.7. Masking

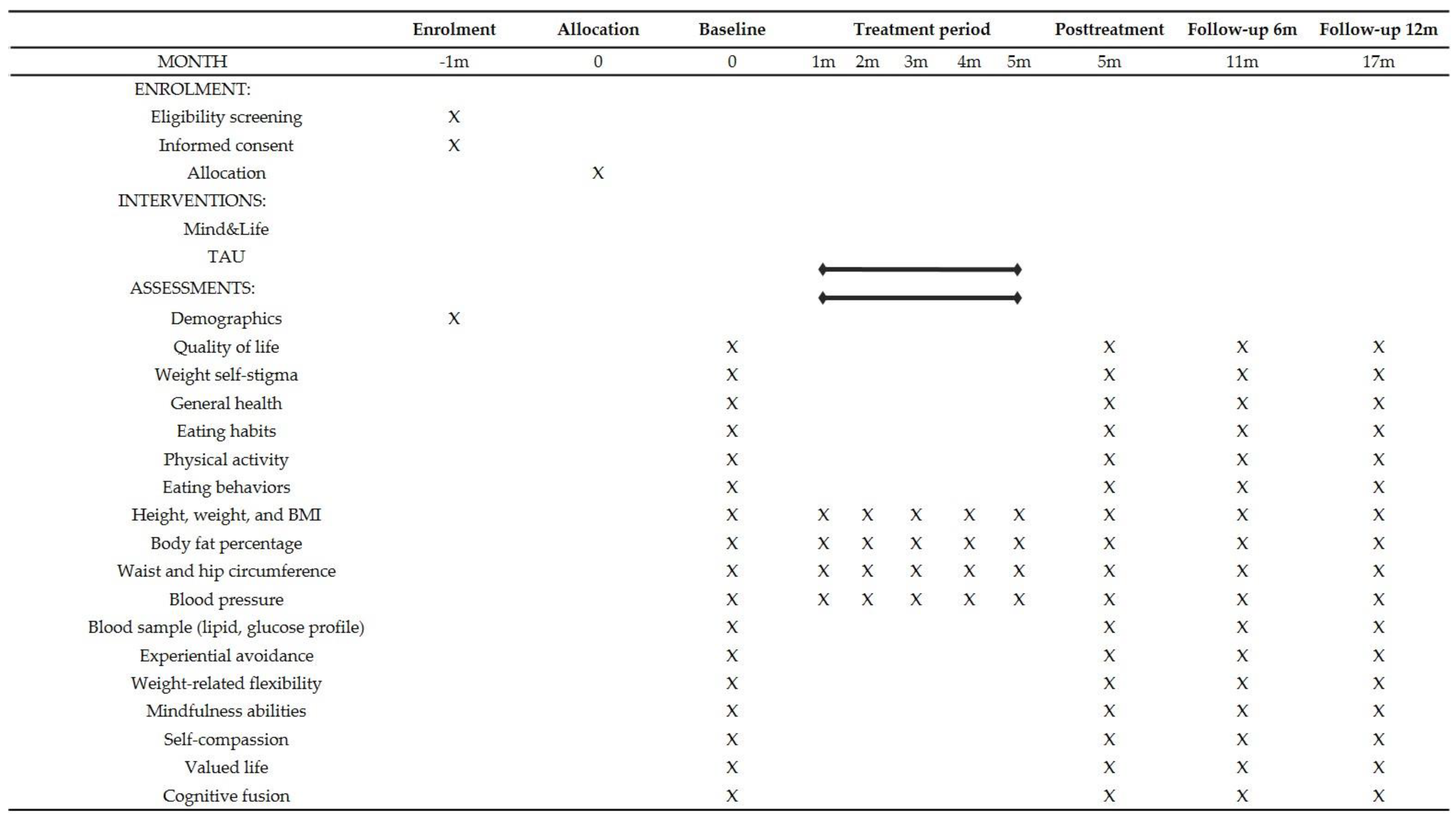

2.8. Data Collection and Assessment Plans

2.8.1. Enrollment Criteria and Baseline Characteristics

Demographics

Weight-Related Information

Participation Motivation

2.8.2. Primary Outcomes and Measures

Quality of Life

Weight Self-Stigma

General Health

Eating Habits

Physical Exercise

Eating Behavior

2.8.3. Secondary Outcomes and Measures

BMI

Body Fat Percentage

Waist and Hip Circumference

Blood Pressure

Lipid Profile

Glucose Level

Insulin Sensitivity

2.8.4. Process Outcomes and Measures

Experiential Avoidance

Weight-Related Flexibility

Mindfulness Abilities

Self-Compassion

Valued Life

Cognitive Fusion

2.9. Data Management

2.10. Data Analysis

2.11. Dissemination

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abarca-Gómez, L.; Abdeen, Z.A.; Hamid, Z.A.; Abu-Rmeileh, N.M.; Acosta-Cazares, B.; Acuin, C.; Adams, R.J.; Aekplakorn, W.; Afsana, K.; Aguilar-Salinas, C.A. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017, 390, 2627–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; EU. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle; OECD Publishing: Paris, France; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withrow, D.; Alter, D.A. The economic burden of obesity worldwide: A systematic review of the direct costs of obesity. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busutil, R.; Espallardo, O.; Torres, A.; Martínez-Galdeano, L.; Zozaya, N.; Hidalgo-Vega, Á. The impact of obesity on health-related quality of life in Spain. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2017, 15, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magallares, A.; Benito de Valle, P.; Irles, J.A.; Jauregui-Lobera, I. Overt and subtle discrimination, subjective well-being and physical health-related quality of life in an obese sample. Span. J. Psychol. 2014, 17, E64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alimoradi, Z.; Golboni, F.; Griffiths, M.D.; Broström, A.; Lin, C.; Pakpour, A.H. Weight-related stigma and psychological distress: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 39, 2001–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhangi, M.A.; Emam-Alizadeh, M.; Hamedi, F.; Jahangiry, L. Weight self-stigma and its association with quality of life and psychological distress among overweight and obese women. Eat. Weight Disord. 2017, 22, 451–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordmo, M.; Danielsen, Y.S.; Nordmo, M. The challenge of keeping it off, a descriptive systematic review of high-quality, follow-up studies of obesity treatments. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e12949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesi, L.; El Ghoch, M.; Brodosi, L.; Calugi, S.; Marchesini, G.; Dalle Grave, R. Long-term weight loss maintenance for obesity: A multidisciplinary approach. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2016, 9, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombrowski, S.U.; Knittle, K.; Avenell, A.; Araujo-Soares, V.; Sniehotta, F.F. Long term maintenance of weight loss with non-surgical interventions in obese adults: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2014, 348, g2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dammen, L.; Wekker, V.; de Rooij, S.R.; Mol, B.W.J.; Groen, H.; Hoek, A.; Roseboom, T.J. The effects of a pre-conception lifestyle intervention in women with obesity and infertility on perceived stress, mood symptoms, sleep and quality of life. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillot, A.; Romain, A.J.; Boisvert-Vigneault, K.; Audet, M.; Baillargeon, J.P.; Dionne, I.J.; Valiquette, L.; Abou Chakra, C.N.; Avignon, A.; Langlois, M. Effects of lifestyle interventions that include a physical activity component in class II and III obese individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasikiewicz, N.; Myrissa, K.; Hoyland, A.; Lawton, C. Psychological benefits of weight loss following behavioural and/or dietary weight loss interventions. A systematic research review. Appetite 2014, 72, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazzeretti, L.; Rotella, F.; Pala, L.; Rotella, C.M. Assessment of psychological predictors of weight loss: How and what for? World J. Psychiatry 2015, 5, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines: Effective Psychological and Behavioural Interventions in Obesity Management. Available online: https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/behavioural (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Comșa, L.; David, O.; David, D. Outcomes and mechanisms of change in cognitive-behavioral interventions for weight loss: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Behav. Res. Ther. 2020, 132, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, A.; Moullec, G.; Lavoie, K.L.; Laurin, C.; Cowan, T.; Tisshaw, C.; Kazazian, C.; Raddatz, C.; Bacon, S.L. Impact of cognitive-behavioral interventions on weight loss and psychological outcomes: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018, 37, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffitt, R.; Haynes, A.; Mohr, P. Treatment beliefs and preferences for psychological therapies for weight management. J. Clin. Psychol. 2015, 71, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vocks, S.; Tuschen-Caffier, B.; Pietrowsky, R.; Rustenbach, S.J.; Kersting, A.; Herpertz, S. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of psychological and pharmacological treatments for binge eating disorder. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnuovo, G.; Pietrabissa, G.; Manzoni, G.M.; Cattivelli, R.; Rossi, A.; Novelli, M.; Varallo, G.; Molinari, E. Cognitive behavioral therapy to aid weight loss in obese patients: Current perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2017, 10, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M.; Mottershead, T.; Ronksley, P.; Sigal, R.; Campbell, T.; Hemmelgarn, B. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnes, R.; Ivezaj, V. A systematic review of motivational interviewing for weight loss among adults in primary care. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, P.; Gómez, N.; Nicoletti, D.; Cerda, R. ¿Es efectiva la entrevista motivacional individual en la malnutrición por exceso? Una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Aten. Prim. 2019, 51, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newnham-Kanas, C.; Irwin, J.D.; Morrow, D.; Battram, D. The quantitative assessment of motivational interviewing using co-active life coaching skills as an intervention for adults struggling with obesity. Int. Coach. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 6, 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor, E.R.; Islam, N.; Bates, S.; Griffin, S.J.; Hill, A.J.; Hughes, C.A.; Sharp, S.J.; Ahern, A.L. Third-wave cognitive behaviour therapies for weight management: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2020, 21, e13013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, S.C. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Relational Frame Theory, and the Third Wave of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. Behav. Ther. 2004, 35, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, E.M.; Butryn, M.L. A new look at the science of weight control: How acceptance and commitment strategies can address the challenge of self-regulation. Appetite 2015, 84, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, J.; Kendra, K.E. Acceptance and commitment therapy for weight control: Model, evidence, and future directions. J. Context. Behav. Sci. 2014, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, J.; Dallal, D.H.; Forman, E.M. Innovations in Applying ACT Strategies for Obesity and Physical Activity. In Innovations in Acceptance & Commitment Therapy: Clinical Advancements and Applications in ACT; Levin, M.E., Twohig, M.P., Krafft, J., Eds.; Context Press: Reno, NV, USA, 2020; pp. 126–139. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, E.M.; Manasse, S.M.; Butryn, M.L.; Crosby, R.D.; Dallal, D.H.; Crochiere, R.J. Long-term follow-up of the Mind Your Health project: Acceptance-based versus standard behavioral treatment for obesity. Obesity 2019, 27, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, E.M.; Butryn, M.L.; Juarascio, A.S.; Bradley, L.E.; Lowe, M.R.; Herbert, J.D.; Shaw, J.A. The Mind Your Health project: A randomized controlled trial of an innovative behavioral treatment for obesity. Obesity 2013, 21, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, J.; Niemeier, H.M.; Thomas, J.G.; Unick, J.; Ross, K.M.; Leahey, T.M.; Kendra, K.E.; Dorfman, L.; Wing, R.R. A randomized trial of an acceptance-based behavioral intervention for weight loss in people with high internal disinhibition. Obesity 2016, 24, 2509–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayn, M.; Knäuper, B. Emotional eating and weight in adults: A review. Curr. Psychol. 2018, 37, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sairanen, E.; Tolvanen, A.; Karhunen, L.; Kolehmainen, M.; Järvelä-Reijonen, E.; Lindroos, S.; Peuhkuri, K.; Korpela, R.; Ermes, M.; Mattila, E.; et al. Psychological flexibility mediates change in intuitive eating regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy interventions. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrière, K.; Khoury, B.; Günak, M.M.; Knäuper, B. Mindfulness-based interventions for weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.M.; Ferrari, M.; Mosely, K.; Lang, C.P.; Brennan, L. Mindfulness-based interventions for adults who are overweight or obese: A meta-analysis of physical and psychological health outcomes. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Wang, Z. Mindfulness capability mediates the association between weight-based stigma and negative emotion symptoms. Mindfulness 2019, 10, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.; Hill, M.L. Mindfulness as therapy for disordered eating: A systematic review. Neuropsychiatry 2013, 3, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, L.; Cunha, M.; Pinto-Gouveia, J. Processes of change in quality of life, weight self-stigma, body mass index and emotional eating after an acceptance-, mindfulness-and compassion-based group intervention (Kg-Free) for women with overweight and obesity. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 1056–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, C.; Williamson, H.; Zucchelli, F.; Paraskeva, N.; Moss, T. A systematic review of the effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for body image dissatisfaction and weight self-stigma in adults. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2018, 48, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potts, S.; Krafft, J.; Levin, M.E. A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Guided Self-Help for Overweight and Obese Adults High in Weight Self-Stigma. Behav. Modif. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, M.E.; Petersen, J.M.; Durward, C.; Bingeman, B.; Davis, E.; Nelson, C.; Cromwell, S. A randomized controlled trial of online acceptance and commitment therapy to improve diet and physical activity among adults who are overweight/obese. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, ibaa123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, J.; Hayes, S.C.; Bunting, K.; Masuda, A. Teaching acceptance and mindfulness to improve the lives of the obese: A preliminary test of a theoretical model. Ann. Behav. Med. 2009, 37, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, L.; Pinto-Gouveia, J.; Cunha, M. Exploring the efficacy of an acceptance, mindfulness & compassionate-based group intervention for women struggling with their weight (Kg-Free): A randomized controlled trial. Appetite 2017, 112, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, K.; Shaw, C.; Ilsley, J.; Hill, A.J.; Bond, F.W.; Moore, L. Exploratory randomised controlled trial of a mindfulness-based weight loss intervention for women. Appetite 2009, 52, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L.; Annunziato, R.A.; Burgard, D.; Danielsdottir, S.; Shuman, E.; Davis, C.; Calogero, R.M. The weight-inclusive versus weight-normative approach to health: Evaluating the evidence for prioritizing well-being over weight loss. J. Obes. 2014, 2014, 983495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Altman, D.G.; Laupacis, A.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Krleža-Jerić, K.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Mann, H.; Dickersin, K.; Berlin, J.A. SPIRIT 2013 Statement: Defining Standard Protocol Items for Clinical Trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013, 158, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butryn, M.L.; Webb, V.; Wadden, T.A. Behavioral treatment of obesity. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 34, 841–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoma, J.B.; Hayes, S.C.; Walser, R.D. Learning ACT: An Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Skills-Training Manual for Therapists; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Westrup, D.; Wright, M.J. Learning ACT for Group Treatment: An Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Skills Training Manual for Therapists; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, E.M.; Butryn, M.L. Effective Weight Loss: An Acceptance-Based Behavioral Approach, Clinician Guide; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, E.M.; Butryn, M.L. Effective Weight Loss: An Acceptance-Based Behavioral Approach, Workbook; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, J.A.; Afari, N. The Big Book of ACT Metaphors: A Practitioner’s Guide to Experiential Exercises and Metaphors in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy; New Harbinger Publications: Oakland, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, J.D.; Williams, J.M.G.; Segal, Z.V. The Mindful Way Workbook: An 8-Week Program to Free Yourself from Depression and Emotional Distress; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kristeller, J.L.; Wolever, R.Q. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: The conceptual foundation. Eat. Disord. 2010, 19, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés, A.; Saldaña, C.; Mesa, J.; Lecube, A. Psychometric evaluation of the IWQOL-Lite (Spanish version) when applied to a sample of obese patients awaiting bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2012, 22, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lillis, J.; Luoma, J.B.; Levin, M.E.; Hayes, S.C. Measuring weight self-stigma: The Weight Self-stigma Questionnaire. Obesity 2010, 18, 971–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, A.; Pérez-Echeverría, M.J.; Artal, J. Validity of the scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) in a Spanish population. Psychol. Med. 1986, 16, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Izquierdo, D.; Godoy, J.; López-Torrecillas, F.; Sánchez-Barrera, M. Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del “Cuestionario de Salud General de Goldberg-28”. Revista de Psicología de la Salud 2002, 14, 49–71. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; García-Arellano, A.; Toledo, E.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Buil-Cosiales, P.; Corella, D.; Covas, M.I.; Schröder, H.; Arós, F.; Gómez-Gracia, E. A 14-item mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: The PREDIMED trial. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cebolla, A.; Barrada, J.; van Strien, T.; Oliver, E.; Baños, R. Validation of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) in a sample of Spanish women. Appetite 2014, 73, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, F.J.; Langer Herrera, A.I.; Luciano, C.; Cangas, A.J.; Beltrán, I. Measuring experiential avoidance and psychological inflexibility: The Spanish version of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II. Psicothema 2013, 25, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillis, J.; Hayes, S.C. Measuring avoidance and inflexibility in weight related problems. Int. J. Behav. Consult. Ther. 2008, 4, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebolla, A.; García-Palacios, A.; Soler, J.; Guillen, V.; Baños, R.; Botella, C. Psychometric properties of the Spanish validation of the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Eur. J. Psychiat. 2012, 26, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Campayo, J.; Navarro-Gil, M.; Andrés, E.; Montero-Marin, J.; López-Artal, L.; Demarzo, M.M.P. Validation of the Spanish versions of the long (26 items) and short (12 items) forms of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS). Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2014, 12, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, K.; Groom, J. The Valued Living Questionnaire; Department of Psychology, University of Mississippi: Oxford, MS, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Groom, J.; Wilson, K. Examination of the psychometric properties of the Valued Living Questionnaire (VLQ): A tool of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Behavior Analysis, San Francisco, CA, USA, May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Moreno, R.; Marquez-Gonzalez, M.; Losada, A.; Gillanders, D.; Fernandez-Fernandez, V. Cognitive fusion in dementia caregiving: Psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the “Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire”. Behav. Psychol. 2014, 22, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Apovian, C.M. Obesity: Definition, comorbidities, causes, and burden. Am. J. Manag. Care 2016, 22, 176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Bombak, A.; Monaghan, L.F.; Rich, E. Dietary approaches to weight-loss, Health At Every Size® and beyond: Rethinking the war on obesity. Soc. Theory Health 2019, 17, 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearl, R.L.; Puhl, R.M. Weight bias internalization and health: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1141–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Session Number | Content |

|---|---|

| 1 | Eating and physical activity-related instructions and recommendations |

| 2 | Food and physical activity pyramid and Harvard plate |

| 3 | Seasonally adapted weekly menu |

| 4 | Nutritional labelling |

| 5 | Recommendations for maintaining healthy habits |

| Sn 1 | Content and Processes | Key Metaphors and Exercises | Mindfulness Exercises |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Creative hopelessness, values | Man in the hole metaphor | Mindfulness introduction |

| 2 | Control as the problem, willingness as the alternative, values | What are the numbers exercise, fall in love metaphor, polygraph metaphor, tug-of-war with a monster metaphor, butterfly metaphor, my shrinking life space exercise, living in the cottage or in the new house metaphor | Mindful eating |

| 3 | Distress tolerance, willingness, and acceptance, basic emotions, pain vs. suffering, values | Eyes on exercise, two scales metaphor, attending your own funeral metaphor | Contacting the present |

| 4 | The functioning of the mind I, observing thoughts, cognitive defusion | Take your mind for a walk exercise | Mindful eating, leaves on a stream |

| 5 | The functioning of the mind II, have a thought or buy it, cognitive defusion | Passengers on the bus metaphor | Bodily sensations |

| 6 | Values, committed action, distress tolerance | The values-focused vs. the goals-focused life metaphor, values in the trash exercise, urge surfing exercise | Acceptance mindfulness |

| 7 | The observing self, self as context | Paintings in the museum exercise, the label parade exercise, the sky and the weather metaphor | Observing-self |

| 8 | The observing self, self as context, self-compassion | Timeline exercise, chessboard metaphor, identification labels exercise | Mindful eating, Tonglen mindfulness |

| 9 | Acceptance, habit building, psychological flexibility and rigidity, defusion strategies | Change what you can and accept what you cannot exercise | Stay in the present moment, five senses |

| 10 | Review I, values | Physicalizing exercise, foreseeable and flexible answers exercise, milestone metaphor | Mountain mindfulness |

| 11 | Review II, social support management | Swamp metaphor, holding books exercise | Thought mindfulness |

| 12 | Mindless eating and mindful eating enhancement, defusion review | Mirror exercise, physicalizing exercise, unwelcome party guest metaphor | Emotions-centered mindfulness |

| 13 | Emotional eating, obstacles to living actively | Obstacles and strategies to live actively | Mindful eating |

| 14 | Lapse vs. relapse, live with courage, committed action | Epitaph metaphor | Leaves on a stream |

| 15 | Relapses, personal action plan, committed action | Path up the mountain metaphor | Mindful walking |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iturbe, I.; Pereda-Pereda, E.; Echeburúa, E.; Maiz, E. The Effectiveness of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness Group Intervention for Enhancing the Psychological and Physical Well-Being of Adults with Overweight or Obesity Seeking Treatment: The Mind&Life Randomized Control Trial Study Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094396

Iturbe I, Pereda-Pereda E, Echeburúa E, Maiz E. The Effectiveness of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness Group Intervention for Enhancing the Psychological and Physical Well-Being of Adults with Overweight or Obesity Seeking Treatment: The Mind&Life Randomized Control Trial Study Protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(9):4396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094396

Chicago/Turabian StyleIturbe, Idoia, Eva Pereda-Pereda, Enrique Echeburúa, and Edurne Maiz. 2021. "The Effectiveness of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness Group Intervention for Enhancing the Psychological and Physical Well-Being of Adults with Overweight or Obesity Seeking Treatment: The Mind&Life Randomized Control Trial Study Protocol" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 9: 4396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094396

APA StyleIturbe, I., Pereda-Pereda, E., Echeburúa, E., & Maiz, E. (2021). The Effectiveness of an Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness Group Intervention for Enhancing the Psychological and Physical Well-Being of Adults with Overweight or Obesity Seeking Treatment: The Mind&Life Randomized Control Trial Study Protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4396. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094396