Understanding Youth’s Lived Experience of Anxiety through Metaphors: A Qualitative, Arts-Based Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

When I get like really anxious…like I think I’m kind of using anger as a way to explain it even though it’s not exactly it…. Like I said I get angry a lot which I guess I do sometimes, but it’s not exactly anger it’s just something I can’t really describe…. It’s like a feeling, it’s kind of like a mix between anger and like apathetic, like apathy to myself and like stuff like that. It’s just kind of like a mix of a bunch of things that like making my mood kind of like [long sigh]. It’s [anxiety] like when you put a cat inside a bag and they start like clawing at it, I don’t know.

3.1. The Metaphor of Lived Space: A Shrinking World

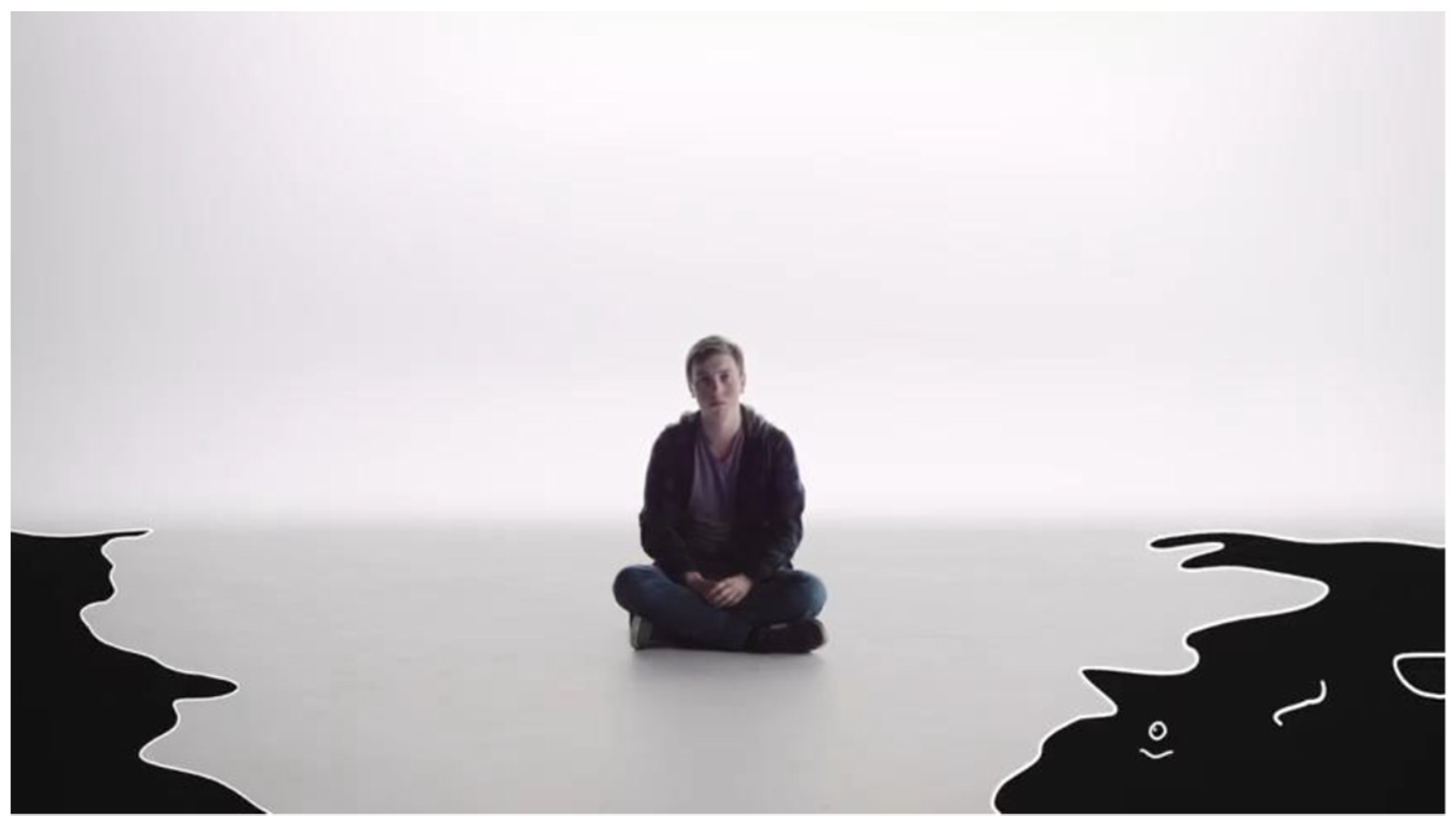

It’s [living with anxiety] like living in a box, and the box keeps on going smaller and smaller every single day…To me in my head when I first think of anxiety it’s like you’re in an empty world and there’s nothing, no one’s around you, you’re trapped in this world that you’re trying to get, you’re screaming for help and no one can hear you…. And it feels like that you’re getting closer to the edge of like of things, you feel like you’re getting closer to the edge of the world and everything and no matter where you walk or step or whatever you do it’s like the world is getting like getting more surrounding you.

Anxiety is like lot of black sludge…Like I see myself sinking a lot of the time. And that’s a common image that I’ve looked at throughout my poetry… I wrote about it in my journal and it’s just a bunch of fears and stuff that I was upset about and really what anxiety and depression look like to me is just black sludge.

This is a screenshot of a railway track with, with pebbles or flowers but some of it glows in the dark and I just thought the idea that like this path that you’re on it can be surrounded by darkness and fear but if like the path itself is like lit and I don’t know I just saw it as like no matter what is horrible or scary or that makes you fear yourself or others around you like as long as you stay on this path and you keep going it’s like a beautiful journey and like as long as you keep going on the path it’s going to keep you safe…. Cause that’s what I see, like the path is the only thing that looks safe in this like field or that looks secure and it looks lit.

3.2. The Metaphor of the Lived Body: The Heavy, Heavy Backpack

…you’re crawling instead of just having that stroll to achieve whatever, you’re almost crawling and almost scraping through the floor, like trying to get there…. Cause anxiety is like riding on your back almost. And you’re like crawling and it’s so heavy…. And like you know I don’t need this luggage, I can stand up straight and get this done…. But it’s just, I guess anxiety is that burden, the heavy heavy backpack on your, its full of things you don’t even need but they are there.

Well when my breathing’s acting up [with anxiety] it feels like, you know how like you’re underwater and your lungs start to get tight…. That’s what it kind of feels like for me…But and then with the guilt like it feels like my stomach has dropped or something like I don’t….

…like just imagine something that makes you really you know just low…. That’s what it feels like you’re slowly collapsing…. Kind of like if you’re made out of sugar and it’s raining or after you get a sugar high and then you start crashing, that’s what happens to me, I get really angry and I put all my energy into fighting and then I sink down.

With anxiety, even if it’s light out, it is just complete darkness… It’s like water that keeps rising, it’s at my chin…Like I’m never out but just keep it from like below my chin instead of going into my mouth, so I keep struggling to paddle my way through.

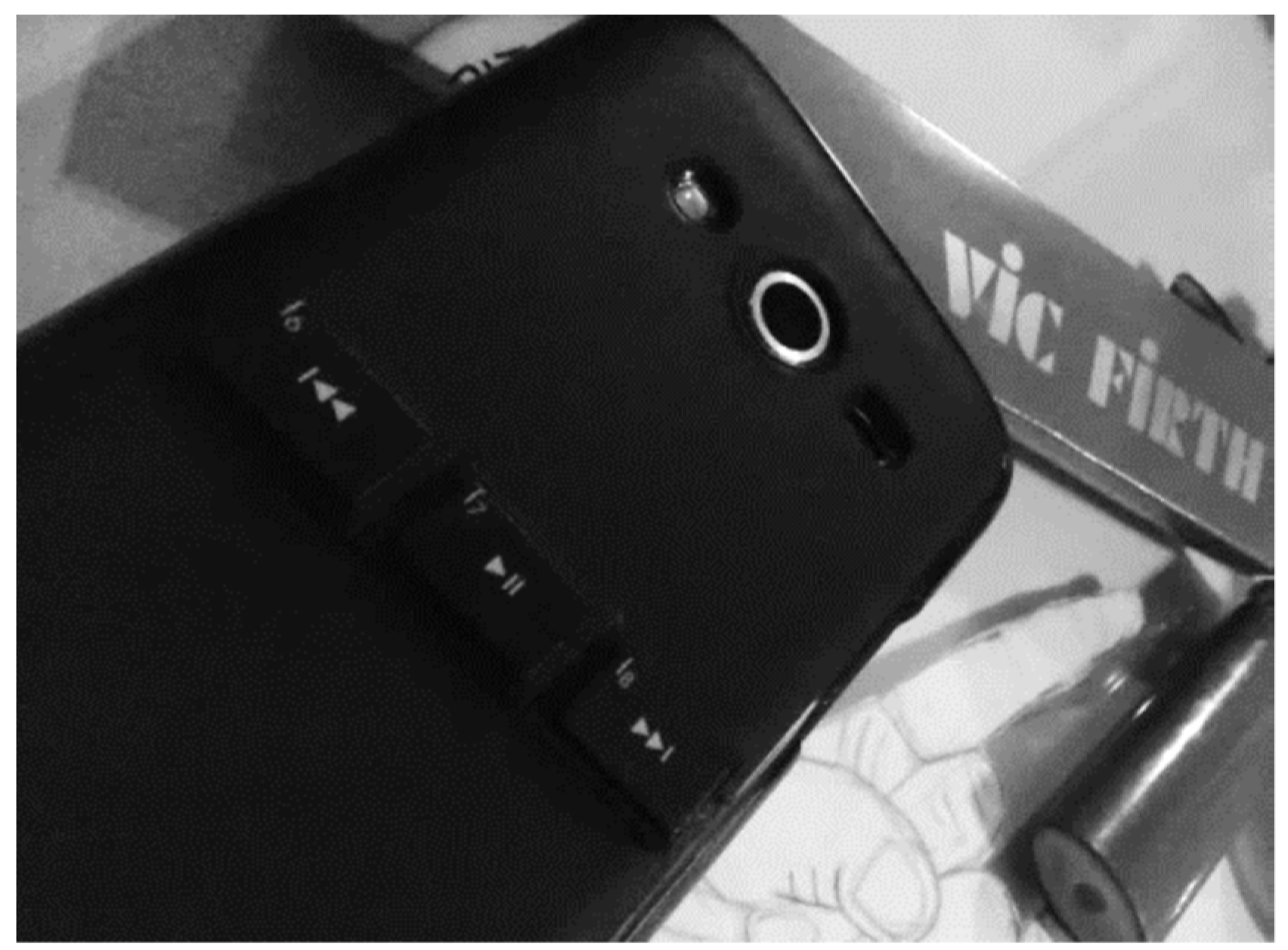

3.3. The Metaphor of Lived Time: Play, Pause, Rewind, Forward

In similar vein, a 16-year-old participant shared:I glued on keys from an old computer…. And I really liked the play pause, rewind and forward…. Just ‘cause it’s like, like start your life as in like play, pause and breathe…. Forward and think in the future…. And rewind and think in the past because that’s everything I kind of do…. Sometimes I just stop and breathe, sometimes I just you know go with it, sometimes I start thinking of good things that could happen in the future or bad things that could happen in the future and sometimes I start thinking of the past and sometimes it’s good or bad

That’s the stop sign at the end of my street (Figure 6). And I just sort of thought like all of the times I feel like I’m just sort of standing and staying in one place, not really making progress in any field of my life… so that sort of represents anxiety and depression…. I’m not really happy being in that moment.

If you notice, there’s two pathways… So even though I’m going out to nature I feel better, as soon as I approached this almost like a fork right…I start feeling anxious again…. Like what way do I take?... Which always represents me in life, there’s, whenever I’m facing a decision it’s one of the worst causes of my anxiety because the what if comes up…. What if I take the wrong path and get lost or, or end up you know causing more problems or you know this and that and you know so many things come up, even though it’s such a beautiful scenery and it’s supposed to make me feel good, it’s just, I stood there going, which way, I mean even though it’s no big deal, I’m just taking a walk, all of a sudden I just thought of wow, like anything that gives, makes me decide…It just it feels horrible inside…I hate deciding.

When the snow melts like automatically expect to see like flowers and green grass and leaves on trees and then I always forget when the snow melts it’s like a long process of everything growing again and it was also kind of like this deeper message to me that you know when the snow melts you can’t automatically expect things to get better right away but like it’s a, like it’s a slow process and as long as you focus on the fact that like things will grow again..…So I feel if you connect yourself to a flower, like you’re dead under this miserable ice and it is like when the ice melts you’re still dead but you can teach yourself to grow again and it’s like I think that’s a really important metaphor.

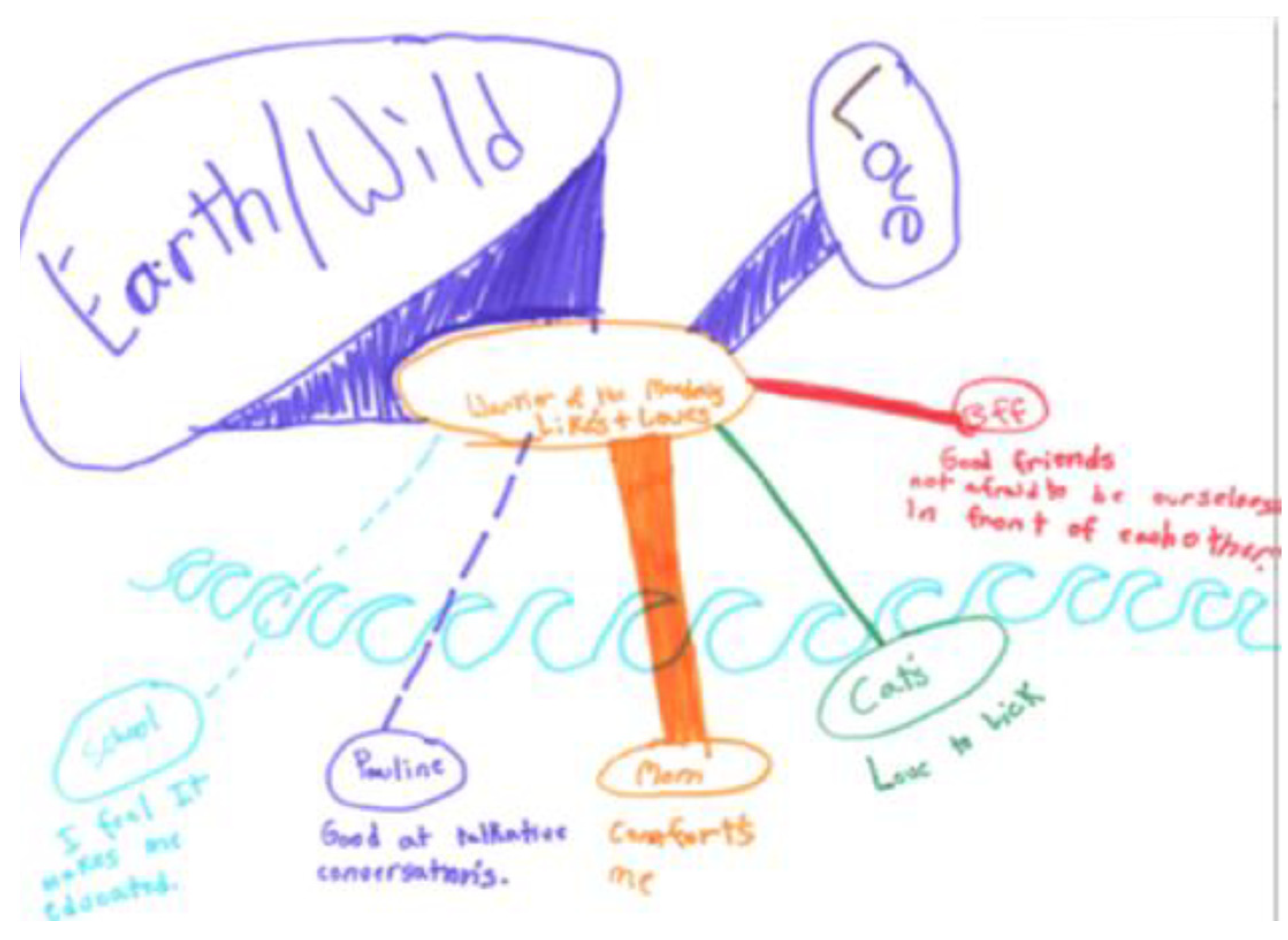

3.4. The Metaphor of Lived Relations: A Fine Balance

At times my anxiety can be represented in a way by those sakura which is cherry blossoms…. And it can be to the point where I can’t talk to people…So there are times where I can approach someone and be with them and, and go about my daily things, but after that the cherry blossoms seem to push me away which is like the anxiety makes me feel like I want to get away from people and it’s too much to handle and so it’s just like its two sides of me (chuckle).

[People] ask you what is like, cause I always get asked, what is anxiety like, I just, I just reply its hell…. It’s like you’re trapped in a world and no one’s there for you, yet they may be but you can’t see them, they can see you but you can’t, it’s like you can’t hear them but like they can’t hear you…. It’s like you want, it’s like they can, like maybe, maybe they can hear you but you just can’t hear them responding saying I’m here to help, I’m here to help.

Oh, this photograph (Figure 10) is technically a picture of a whole bunch of geese…But what I did with this one is I used the geese as a representation. First of all there’s geese everywhere… there was just too many of them so this one I used to represent crowds…. Because I didn’t want to go risk it in the shopping mall or like after a concert or a club or anything, so I thought geese were a safe way to go…. What I really liked about it is that when you’re anxiety and you’re in a crowd you don’t really notice each person individually or you can’t really tell the difference between each person, only know if it’s a person you don’t know and that causes anxiety. So, using geese where they almost all look the same is kind of the best analogy of what it’s like in the eyes of someone with anxiety in a crowd.

3.5. Lived Meaning

But anxiety is like a monster it just creeps up on you…I see kind of see really kind of evil and red swirls…It kind of reminds me of the devil honestly, just a bunch of red swirls. Sometimes I tell the monster, like I don’t care, go bug someone else, not me right now…. o um I don’t know how old I was when I started, I think I was 10…. And I created mine, her name was Candy and she looks so sweet and beautiful and then she’s just like an evil monster.…. She [monster] came into my head all the time when I had anxiety and I would just say; go away, I don’t want to listen to you, so you need to leave…And then I would also like reach to my head and go like that, like I was pulled her out or something… And then I would just, I would lock my brain [motions as if turning a key] and be like okay you can’t get into my head now…I don’t know what, it just helped with like, oh she’s not in my head anymore, oh whoa and then I’ll just get distracted by something else.

This one is a picture of what anxiety kind of sort of looks like in my head…It looks like a monster (chuckle)…. Especially when you don’t have any skills to deal with anxiety yet, it’s just a big bad scary monster…. It depends on the day you ask me, sometimes anxiety feels like a monster inside of me and sometimes anxiety, if I go without anxiety for a long time it will be like the monster is coming back to me.

This one [photograph] is a fire. I was having it at my lake but I thought it was a good picture because I think it represents anxiety pretty well… Anxiety could be provoked by the smallest little thing and it could turn into something big and ugly, so kind of like the smallest little spark can start a fire, but I also put it in the fire pit because what people think that I need to learn is how to control it or how to harness it to do something good. Like I know when I sometimes get anxious I can use that energy positively when I go work out so then I can work out longer or sometimes I use that to focus on something that I really need to do and I thought that was a good way of describing what can happen with anxiety. Another thing that can happen with anxiety if we don’t control it can be damaging to us and anything around us, just like fire can be damaging.

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Belfer, M.L. Child and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, W.; Dean, A.J.; Najman, J.; Hayatbakhsh, R. Are child and adolescent mental health problems increasing in the 21st century? A systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2014, 48, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polanczyk, G.V.; Salum, G.A.; Sugaya, L.S.; Caye, A.; Rohde, L.A. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2015, 56, 345–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiens, K.; Bhattarai, A.; Pedram, P.; Dores, A.; Williams, J.; Bulloch, A.; Patten, S. A growing need for youth mental health services in Canada: Examining trends in youth mental health from 2011 to 2018. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costello, E.J.; Egger, H.L.; Angold, A. The developmental epidemiology of anxiety disorders: Phenomenology, prevalence, and comorbidity. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 14, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Lopez, L.-J.; Bonilla, N.; Muela-Martinez, J.-A. Considering comorbidity in adolescents with social anxiety disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2016, 13, 574–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, C.M.; Caporino, N.E.; Kendall, P.C. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 816–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyre, O.; Thapar, A. Common adolescent mental disorders: Transition to adulthood. Lancet 2014, 383, 1366–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Dupuis, G.; Piche, J.; Clayborne, Z.; Colman, I. Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: A systematic review. Depress. Anxiety 2018, 35, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, S.S.; Pedersen, G.A.; Ottman, K.; Burgess, A.; Gautam, K.; Martini, T.; Viduani, A.; Momodu, O.; Lam, C.; Fisher, H.L. Detection of risk for depression among adolescents in diverse global settings: Protocol for the IDEA qualitative study in Brazil, Nepal, Nigeria and the UK. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroz, E.E.; Ritchey, M.; Bass, J.K.; Kohrt, B.A.; Augustinavicius, J.; Michalopoulos, L.; Burkey, M.D.; Bolton, P. How is depression experienced around the world? A systematic review of qualitative literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 183, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Tennent, P.; Barriage, S.; Legras, N. The lived experience of anxiety and the many facets of pain: A qualitative, arts-based approach. Can. J. Pain 2020, 4, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L. Living in the shadow of fear: Adolescents’ lived experience of depression. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, K.; Carless, D. Engaging with arts-based research: A story in three parts. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2018, 15, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckeon, R.P. The Basic Works of Aristotele; Bywater, I., Translator; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Kirklin, D. Truth telling, autonomy and the role of metaphor. J. Med. Ethics 2007, 33, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricœur, P. The Rule of Metaphor: The Creation of Meaning in Language, 3rd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Czechmeister, C.A. Metaphor in illness and nursing: A two-edged sword. A discussion of the social use of metaphor in everyday language, and implications of nursing and nursing education. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 1226–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.L.; Estes, Z. Roosters, robins, and alarm clocks: Aptness and conventionality in metaphor comprehension. J. Mem. Lang. 2006, 55, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, M.S.; Manfredi, D.A. Topic—vehicle interaction in metaphor comprehension. Mem. Cogn. 2001, 29, 1209–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappe, D.; Kennedy, J.M.; Smykowski, T. Reversibility, aptness, and the conventionality of metaphors and similes. Metaphor Symb. 2003, 18, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glucksberg, S. How metaphors create categories—Quickly. In Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought; Gibbs, R., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappe, D.L.; Chiappe, P. The role of working memory in metaphor production and comprehension. J. Mem. Lang. 2007, 56, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall-Taylor, N.; Haydon, A. Using metaphor to translate the science of resilience and developmental outcomes. Public Underst. Sci. 2016, 25, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live By; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Honeck, R.P. Introduction: Figurative language and cognitive science-Past, present, and future. Metaphor Symb. Act. 1996, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. Why metaphor matters to philosophy. Metaphor Symb. Act. Spec. Issue 1995, 10, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortony, A. Metaphor and Thought; Cambridge University Press: New York, NT, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Arroliga, A.C.; Newman, S.; Longworth, D.L.; Stoller, J.K. Metaphorical medicine: Using metaphors to enhance communication with patients who have pulmonary disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 2002, 137, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macagno, F.; Rossi, M.G. Metaphors and problematic understanding in chronic care communication. J. Pragmat. 2019, 151, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macagno, F.; Zavatta, B. Reconstructing metaphorical meaning. Argumentation 2014, 28, 453–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag, S. AIDS and Its Metaphors; Penguin, Harmondsworth: Middlesex, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sontag, S. Illness as a Metaphor; Penguin, Harmondsworth: Middlesex, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Demjén, Z.; Semino, E. Using metaphor in healthcare. In The Routledge Handbook of Metaphor and Language; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 385–399. [Google Scholar]

- Reisfield, G.M.; Wilson, G.R. Use of metaphor in the discourse on Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 4024–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, T. Your father’s a fighter; Your daughter’s a vegetable: A critical analysis of the use of metaphor in clinical practice. Hastings Cent. Rep. 2020, 50, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salis, P.; Ervas, F. Evidence, defeasibility, and metaphors in diagnosis and diagnosis communication. Topoi 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyddon, W.J.; Clay, A.L.; Sparks, C.L. Metaphor and change in counseling. J. Couns. Dev. 2001, 79, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainsilber, L.; Ortony, A. Metaphorical uses of language in the expression of emotions. Metaphor Symb. Act. 1987, 2, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, D. Affective engagement in metaphorical versus literal communication styles in counseling. Discourse Process. 2019, 57, 360–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, J.R.; Raymond, W.; Franks, H. Embodied metaphor in women’s narratives about their experiences with cancer. Health Commun. 2002, 14, 139–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teucher, U. The therapeutic psychopoetics of cancer metaphors: Challenges in interdisciplinarity. Hist. Intellect. Cult. 2003, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Locock, L.; Mazanderani, F.; Powell, J. Metaphoric language and the articulation of emotions by people affected by motor neurone disease. Chronic Illn. 2012, 8, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castaño, E. Discourse analysis as a tool for uncovering the lived experience of dementia: Metaphor framing and well-being in early-onset dementia narratives. Discourse Commun. 2020, 14, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullo, S. “I feel like I’m being stabbed by a thousand tiny men”: The challenges of communicating endometriosis pain. Health 2020, 24, 476–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munday, I.; Newton-John, T.; Kneebone, I. ‘Barbed wire wrapped around my feet’: Metaphor use in chronic pain. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 814–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, L.; Flynn, M. Searching for the new normal: Exploring the role of language and metaphors in becoming a cancer survivor. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2014, 18, 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinebourne, P.; Smith, J.A. Images of addiction and recovery: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of the experience of addiction and recovery as expressed in visual images. Drugs: Educ. Prev. Policy 2011, 18, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn-Beardsley, J.; Rennick-Egglestone, S.; Callard, F.; Crawford, P.; Farkas, M.; Hui, A.; Manley, D.; McGranahan, R.; Pollock, K.; Ramsay, A.; et al. Characteristics of mental health recovery narratives: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fixsen, A.M.; Ridge, D. Stories of hell and healing: Internet users’ construction of benzodiazepine distress and withdrawal. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 2030–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazard, A.J.; Bamgbade, B.A.; Sontag, J.M.; Brown, C. Using visual metaphors in health messages: A strategy to increase effectiveness for mental illness communication. J. Health Commun. 2016, 21, 1260–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, S.; Saji, S. Capturing alternate realities: Visual metaphors and patient perspectives in graphic narratives on mental illness. J. Graph. Nov. Comics 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forceville, C. Metaphor in pictures and multimodal representations. In The Cambridge Handbook of Metaphor and Thought; Gibbs, R.Q., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 462–482. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, P. The puzzle of metaphor and voice in arts-based social research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2010, 13, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, K. Participatory action research and photovoice in a psychiatric nursing/clubhouse collaboration exploring recovery narrative. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 785–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizock, L.; Russinova, Z.; Shani, R. New roads paved on losses: Photovoice perspectives about recovery from mental illness. Qual. Health Res. 2014, 24, 1481–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.B. Client Use of Metaphor in Selected Recovery Narratives. Ph.D. Thesis, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Leary, D.E. Metaphors in the History of Psychology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Busolo, D.S. Healthy Canadian adolescents’ perspectives of cancer using metaphors: A qualitative study. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.J. An introduction to medical phenomenology: I can’t hear you while I’m listening. Ann. Intern. Med. 1985, 103, 606–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams Camus, J.T. Metaphors of cancer in scientific popularization articles in the British press. Discourse Stud. 2009, 11, 465–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Routledge: London, UK, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Van Manen, M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy; Althouse Press: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jepsen Trangsrud, L.K.; Borg, M.; Bratland-Sanda, S.; Klevan, T. Embodying Experiences with Nature in Everyday Life Recovery for Persons with Eating Disorders. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustakas, C.E. Phenomenological Research Methods; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Berndtsson, I.C. Considering the concepts of the lived body and the lifeworld as tools for better understanding the meaning of assistive technology in everyday life. Alter 2018, 12, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Manen, M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy, 2nd ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res. Nurs. Health 1995, 18, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, J.M.; Field, P.A. Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Gentles, S.J.; Charles, C.; Ploeg, J.; McKibbon, K. Sampling in qualitative research: Insights from an overview of the methods literature. Qual. Rep. 2015, 20, 1772–1789. [Google Scholar]

- Guetterman, T.C. Descriptions of sampling practices within five approaches to qualitative research in education and the health sciences. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasileiou, K.; Barnett, J.; Thorpe, S.; Young, T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, R. Introducing Qualitative Research: A Student Guide to the Craft of Doing Qualitative Research; SAGE: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Munhall, P.L. Revisioning Phenomenology: Nursing and Health Science Research; National League for Nursing Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rempel, G.R.; Neufeld, A.; Kushner, K.E. Interactive use of genograms and ecomaps in family caregiving research. J. Fam. Nurs. 2007, 13, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Burris, M.A. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ. Behav. 1997, 24, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Zurba, M.; Tennent, P. Worth a thousand words? Advantages, challenges and opportunities in working with photovoice as a qualitative research method with youth and their Families. Forum Qual. Soz. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felner, J.K.; Kieu, T.; Stieber, A.; Call, H.; Kirkland, D.; Farr, A.; Calzo, J.P. “It’s Just a Band-Aid on Something No One Really Wants to See or Acknowledge”: A Photovoice Study with Transitional Aged Youth Experiencing Homelessness to Examine the Roots of San Diego’s 2016–2018 Hepatitis A Outbreak. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leavy, P. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice, 3rd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CohenMiller, A.S. Visual arts as a tool for phenomenology. Forum Qual. Soz. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2018, 19, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronzi, S.; Pope, D.; Orton, L.; Bruce, N. Using photovoice methods to explore older people’s perceptions of respect and social inclusion in cities: Opportunities, challenges and solutions. SSM-Popul. Health 2016, 2, 732–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverty, S.M. Hermeneutic phenomenology and phenomenology: A comparison of historical and methodological considerations. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2003, 2, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, R.; Manias, E. Snap-shots of live theatre: The use of photography to research governance in operating room nursing. Nurs. Inq. 2003, 10, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Tennent, P. The Monster; Twenty Different Emotions; Overthinking; Trapped in an Empty World; Fighting to Stay on the Path. Youth Voices: What It Is Like to Live with Anxiety. 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/2OQncBB (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- Woodgate, R.L.; Tennent, P.; Jacques, P.A. Hiding the struggle; Fear of the unknown; Taking up space; Feeling different; and Can’t You See I’m Struggling. A Day in the Life of a Young Person with Anxiety. 2017. Available online: http://bit.ly/youthanxietystudy, http://bit.ly/youthanxietystudyfr, http://bit.ly/youthanxietycree (accessed on 1 December 2020).

- van Manen, M. From meaning to method. Qual. Health Res. 1997, 7, 345–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Tailor, K.; Tennent, P.; Wener, P.; Altman, G. The experience of the self in Canadian youth living with anxiety: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leone, D.; Ray, S.; Evans, M. The lived experience of anxiety among late adolescents during high school: An interpretive phenomenological inquiry. J. Holist. Nurs. 2013, 31, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yli-Länttä, H. Young people’s experiences of social fears. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2020, 25, 1022–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.; DeYoung, K.A.; Islam, S.; Anderson, A.S.; Barstead, M.G.; Shackman, A.J. Social context and the real-world consequences of social anxiety. Psychol. Med. 2019, 50, 1989–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiff, S. Art-based research. In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues; Knowles, J.G., Cole, A.L., Eds.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves, S. From art for arts sake to art as means of knowing: A rationale for advancing arts-based methods in research, practice and pedagogy. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2014, 12, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Coholic, D.; Schinke, R.; Oghene, O.; Dano, K.; Jago, M.; McAlister, H.; Grynspan, P. Arts-based interventions for youth with mental health challenges. J. Soc. Work 2019, 20, 269–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, S.H. Assessing anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Child. Adolesc. Ment. Health 2018, 23, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; Skarlato, O. “It is about being outside”: Canadian youth’s perspectives of good health and the environment. Health Place 2015, 31, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M.G. Metaphors for patient education. A pragmatic-argumentative approach applying to the case of diabetes care. Riv. Ital. Di Filos. Del Ling. 2016, 10, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn, N. How to reconstruct schemas people share, from what they say. In Finding Culture in Talk: A Collection of Methods; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 35–82. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley, N.; Parkinson, S.; Holmes, J.; Stapley, E.; Eatough, V.; Target, M. Beyond a diagnosis: The experience of depression among clinically-referred adolescents. J. Adolesc. 2015, 44, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, T.V.; Lubman, D.I.; Clark, E. The experience of young people with depression: A qualitative study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2012, 19, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakakou-Koutsonikou, N.; Williams, J.M. Children and young people’s conceptualizations of depression: A systematic review and narrative meta-synthesis. Child Care Health Dev. 2017, 43, 161–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, M.E.; Ravid, A.; Gibb, B.; George-Denn, D.; Bronstein, L.R.; McLeod, S. Adolescent mental health literacy: Young people’s knowledge of depression and social anxiety disorder. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 58, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calear, A.L.; Batterham, P.J.; Torok, M.; McCallum, S. Help-seeking attitudes and intentions for generalised anxiety disorder in adolescents: The role of anxiety literacy and stigma. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, V. The uses of research in policy and practice and commentaries. Soc. Policy Rep. 2012, 26, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R.W.; Walker, K.C.; Rusk, N.; Diaz, L.B. Understanding youth development from the practitioner’s point of view: A call for research on effective practice. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2015, 19, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B.; Jones, L.; Jones, A.; Corbett, C.E.; Booker, T.; Wells, K.B.; Collins, B. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, J.; Monahan, C.; Monahan, M.; Murphy, R.; Ferguson, S.; Lee, K.; Bennett, A.; Gibbons, P.; Higgins, A. “The Road We Travel”: Developing a co-produced narrative for a photovoice project. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galasiński, D. No mental health research without qualitative research. Lancet Psychiatry 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.L.; West, C.H.; Tailor, K. Existential anxiety and growth: An exploration of computerized drawings and perspectives of children and adolescents with cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2014, 37, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Woodgate, R.L.; Tennent, P.; Legras, N. Understanding Youth’s Lived Experience of Anxiety through Metaphors: A Qualitative, Arts-Based Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084315

Woodgate RL, Tennent P, Legras N. Understanding Youth’s Lived Experience of Anxiety through Metaphors: A Qualitative, Arts-Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084315

Chicago/Turabian StyleWoodgate, Roberta Lynn, Pauline Tennent, and Nicole Legras. 2021. "Understanding Youth’s Lived Experience of Anxiety through Metaphors: A Qualitative, Arts-Based Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084315

APA StyleWoodgate, R. L., Tennent, P., & Legras, N. (2021). Understanding Youth’s Lived Experience of Anxiety through Metaphors: A Qualitative, Arts-Based Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084315