Intergenerational Factors Influencing Household Cohabitation in Urban China: Chengdu

Abstract

1. Introduction

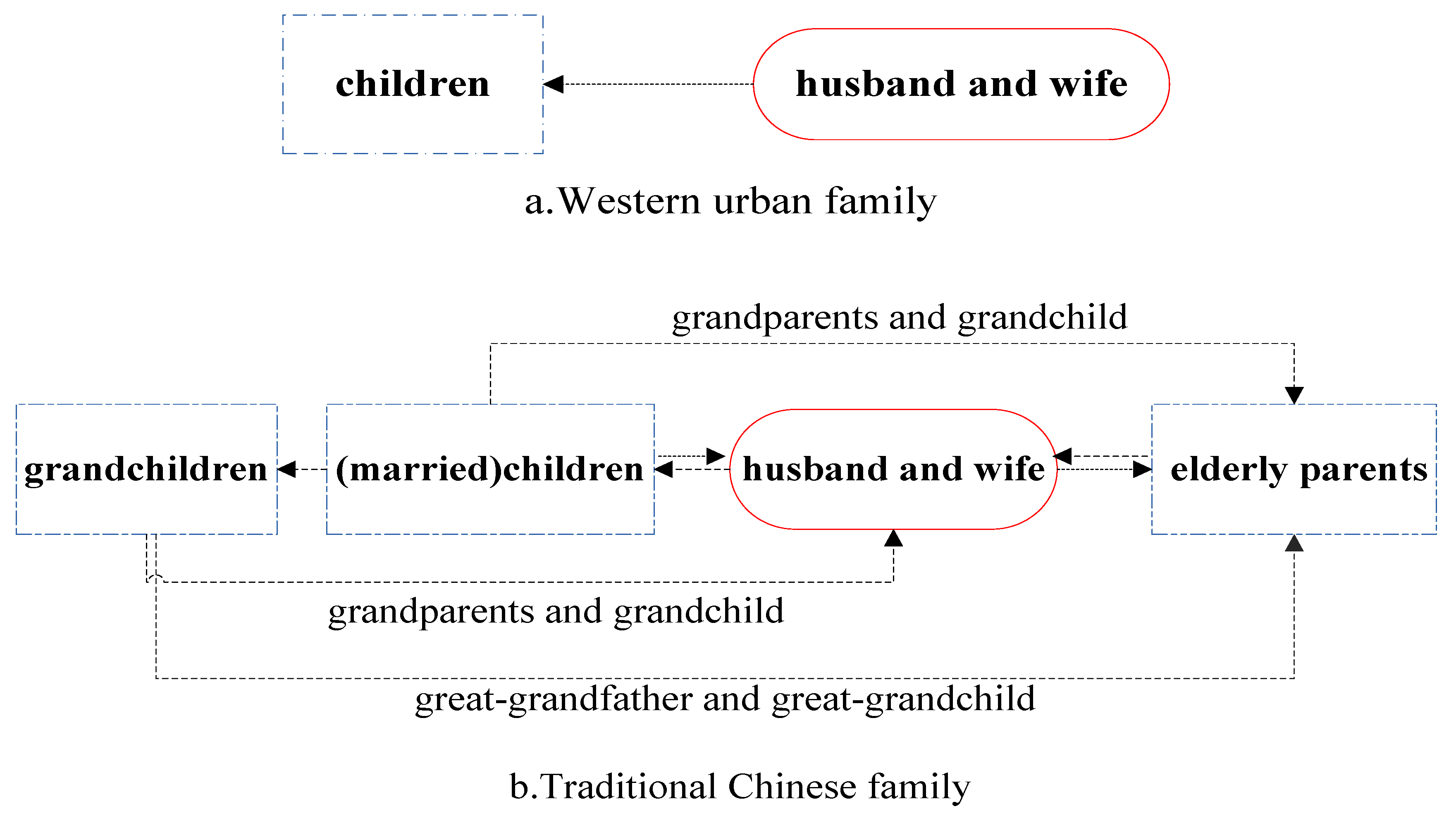

2. Literature Review

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Study Setting

3.2. Data Collection

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Analysis

4.2. Spatial and Temporal Changes in Intergenerational Household Cohabitation from 2000 to 2010

4.3. Distribution of Intergenerational Household Cohabitation According to Age

4.4. Intergenerational Factors in Household Cohabitation

4.4.1. Intergenerational Factors in Household Cohabitation

4.4.2. Descriptive Statistics

4.4.3. Multiple Logistic Regression Results

- (1)

- Inadequate housing has a significant impact on the group of elderly living with unmarried children, and elderly living with grandchildren, as expected, with a positive effect on the former (B = 0.612) and a negative effect on the latter (B = −0.861). Thus, in the face of inadequate housing, the elderly are inclined to live with unmarried children or married children.

- (2)

- Saving costs has a positive effect on the group of elderly living with grandchildren (B = 0.346), and the group of elderly living with unmarried children (B = 0.717); i.e., in order to save costs, the elderly will choose to live with unmarried children or grandchildren.

- (3)

- “In case of emergency” has a negative effect on the group of elderly living with grandchildren (B = −0.518), and a positive effect on the group of elder living with unmarried children (B = 0.221); i.e., people want to have someone to take care of them in case of emergency, so the elderly prefer to live with their unmarried or married children.

- (4)

- Enjoyment of living with a big family does not have a significant impact on the group of elderly living with grandchildren, but has a negative effect on the group of elderly living with unmarried children (B = −0.376). Influenced by the “four generations under one roof” typical of Chinese traditional culture, families enjoy having a large family, so the elderly like to live with their married children.

- (5)

- Doing the housework does not have a significant impact on the group of elderly living with grandchildren, but has a positive effect on the group of elderly living with unmarried children (B = 1.087). That is, in order to get help with doing the housework, the elderly like to live with their unmarried children.

- (6)

- Fear of loneliness has a positive effect on the group of elderly living with grandchildren (B = 0.600), and a negative effect on the group of elderly living with unmarried children (B = −0.300). Thus, in order to avoid loneliness, the elderly like to live with their unmarried or married children.

- (7)

- Care for grandchildren has a positive effect on the group of elderly living with grandchildren (B = 0.471), and has no significant impact on the group of elderly living with unmarried children. Thus, when it comes to taking care of grandchildren, elders elect to live with their grandchildren.

- (8)

- Poor health has a positive effect on the group of elderly living with grandchildren (B = 0.418), and the elderly living with unmarried children (B = 0.239). That is, in order to look after elder relatives who are in poor health, the elderly like to live with grandchildren, or unmarried children.

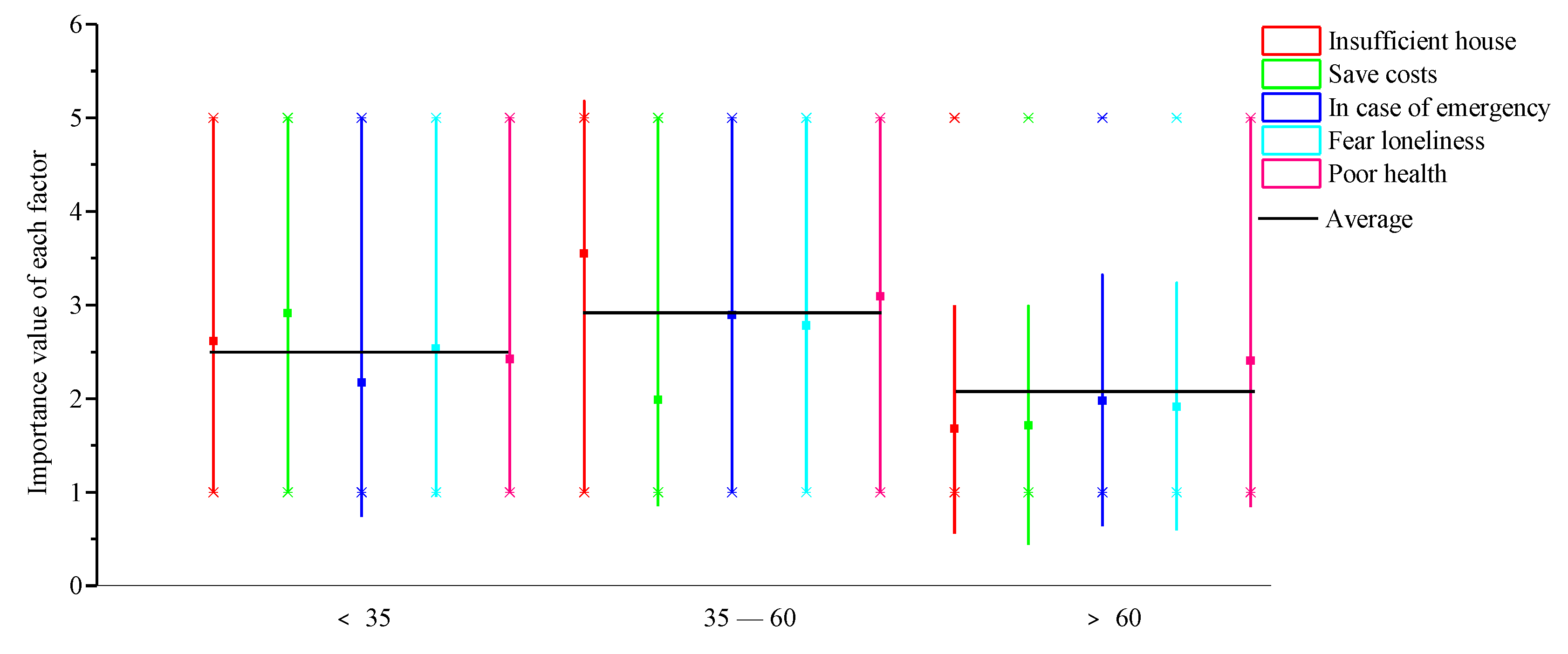

4.4.4. Variation in Intergenerational Factors for Different Groups

- (1)

- Variation between different age groups

- (2)

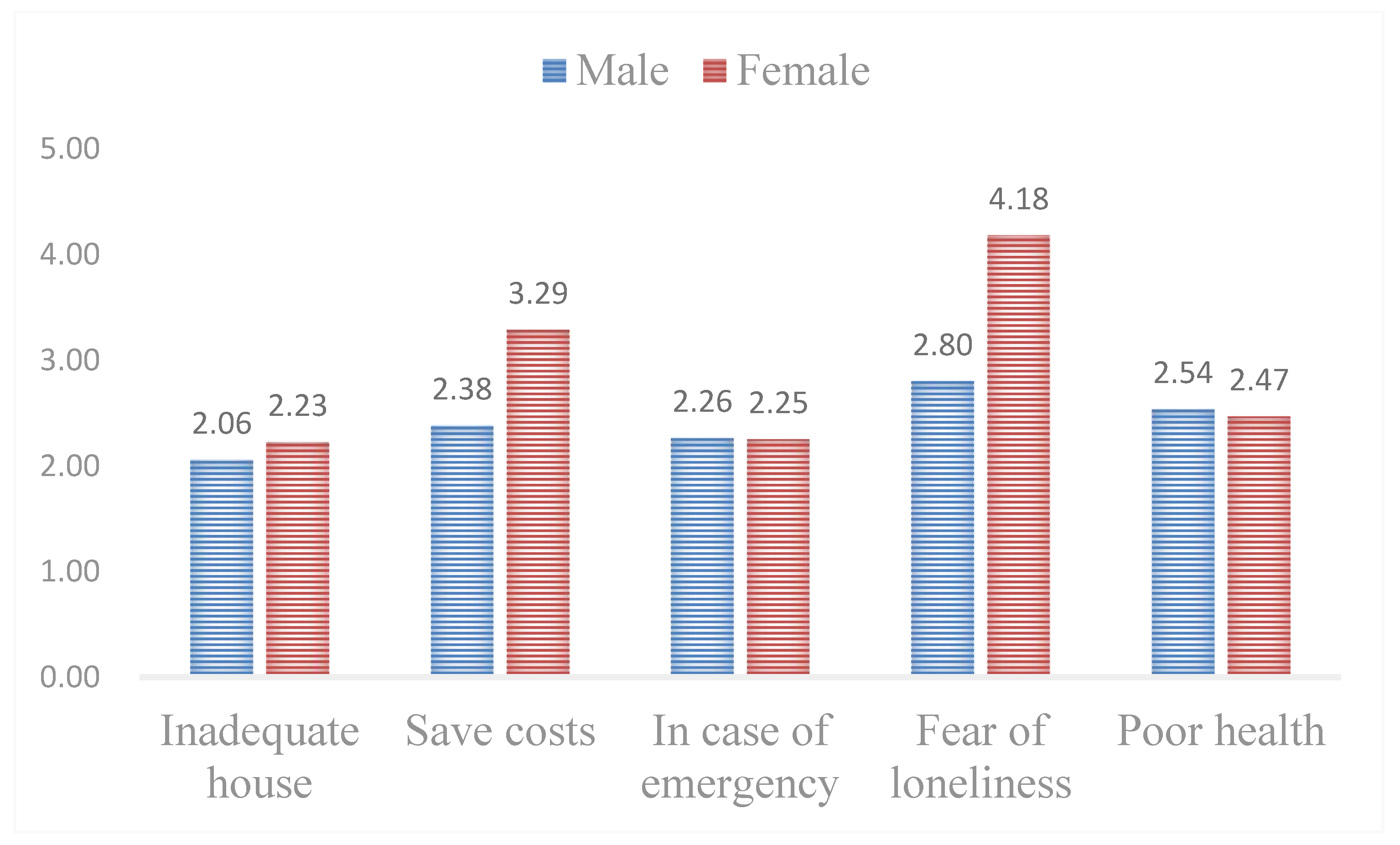

- Variation in gender

- (3)

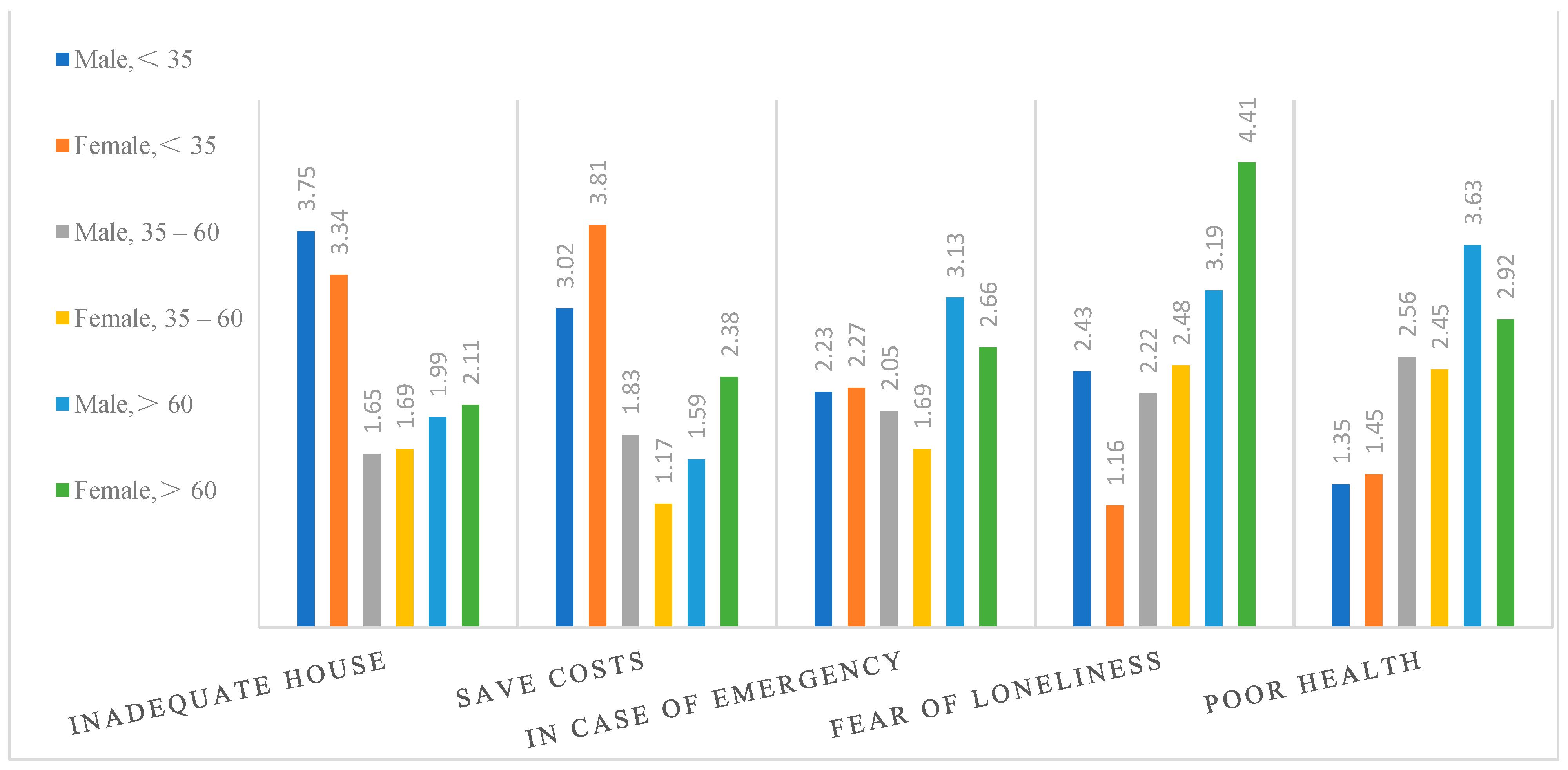

- Variation in groups of all genders and ages

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Jin, S.; Gu, L.; Zhang, H. Social and cultural factors that influence residential location choice of urban senior citizens in China-The case of Chengdu city. Habitat Int. 2016, 53, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.A. Comparative Analysis of the family structure in China’s different regions:Based on the 2010 census data. China Popul. Today 2015, 3, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, Y. Daily life activity space of Hiroshima citizens: A case study of the citizens in their Forties. Jpn. J. Hum. Geogr. 1993, 45, 351–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bao, C.-J.; Guo, X.-L.; Qi, X.; Hu, J.-L.; Zhou, M.-H.; Varma, J.K.; Cui, L.-B.; Yang, H.-T.; Jiao, Y.-J.; Klena, J.D.; et al. A family cluster of infections by a newly recognized bunyavirus in eastern China, 2007: Further evidence of person-to-person transmission. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2011, 53, 1208–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, G. Chinese traditional endowment and its prospect. J. Renmin Univ. China 2000, 5, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Duan, G.X.; Jia, H.L.; Xu, E.S.; Chen, X.M.; Xie, H.H. The level and influencing factors of gerotranscendence in community-dwelling older adults. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2015, 2, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, B.; Vandevusse, A.; Ocobock, A. Family change and the state of family sociology. Curr. Sociol. 2012, 60, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.T.; Kaplowitz, S.A. Family economic status, cultural capital, and academic achievement: The case of Taiwan. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2016, 49, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, S.-J.; Lu, L.-C.; Yen, Y.-Y.; Hsieh, Y.-P.; Chen, J.-C.; Wu, W.J.; Lin, L.-Y. Tube feeding among elder in long-term care facilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2017, 21, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G. China’s Family Problems; The Commerical Press: Beijing, China, 1936. [Google Scholar]

- Elldér, E. Residential location and daily travel distances: The influence of trip purpose. J. Transp. Geogr. 2014, 34, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.K.; Kwan, Y.H. The Utility of Enhancing Filial Piety for Elder Care in China; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, C.K.; Kwan, Y.H. Inducting older adults into volunteer work to sustain their psychological well-being. Ageing Int. 2006, 31, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knodel, R. Living arrangements of older persons around the world united nations population division. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2006, 32, 373–375. [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano, P. Ties That Matter: Cultural Norms and Family Formation in Western Europe; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, C.H.; Kwan, M.L.; Neugut, A.I.; Ergas, I.J.; Wright, J.D.; Caan, B.J.; Hershman, D.; Kushi, L.H. Social networks, social support mechanisms, and quality of life after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2013, 139, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Zhan, H. Filial piety and functional support: Understanding intergenerational solidarity among families with migrated children in rural China. Ageing Int. 2012, 37, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrazzi, E.C.; Motta, T.T.; Vendrúscolo, T.R.; Fabrício-Wehbe, S.C.; Cruz, I.R.; Rodrigues, R.A. Household arrangements of the elder elderly. Rev. Latino-Am. Enferm. 2010, 18, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yu, X.H.Z. Do sons or daughters give more money to parents in urban China? J. Marriage Fam. 2009, 71, 174–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gerland, P.; Raftery, A.E.; Ševčíková, H.; Li, N.; Gu, D.; Spoorenberg, T.; Alkema, L.; Fosdick, B.K.; Chunn, J.; Lalic, N.; et al. World population stabilization unlikely this century. Science 2014, 46, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. Long Lives: Chinese Elder and the Communist Revolution; Stanford University Press: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rowntree, B.S. Poverty: A Study of Town Life; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1901. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz, H.R.; Rossi, P.H. Why Families Move: A Study in the Social Psychology of Urban Residential Mobility. Marriage Fam. Living 1957, 19, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheran, M. The career and family choices of women: A dynamic analysis of labor force participation, schooling, marriage, and fertility decisions. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2007, 10, 367–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.; Raeside, R. Between country variations in self-rated-health and associations with the quality of life of older people: Evidence from the global ageing survey. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2014, 9, 923–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.D. American family and demographic patterns and the northwest European model. Contin. Chang. 1993, 8, 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.S. Modernization and the family structure of the elderly in the United States. Z. Gerontol 1984, 17, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cinotto, S. Everyone would be around the table: American family mealtimes in historical perspective, 1850–1960. New Dir. Child Adolesc. Dev. 2010, 11, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H.; Jimmieson, N.L.; Winter, G. Eldercare demands, mental health, and work performance: The moderating role of satisfaction with eldercare tasks. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2012, 17, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramsson, M.; Andersson, E.K. Residential mobility patterns of elders—Leaving the house for an apartment. Hous. Stud. 2012, 27, 582–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, J.C.; Elvira, D.; MirÃ, O.M. Ageing in place? Exploring elder people’s housing preferences in Spain. Gen. Inf. 2009, 46, 295–316. [Google Scholar]

- Chapleski, E.; Massanari, R.; Herskovitz, L. Facing the Future: 2002 City of Detroit Needs Assessment of Older Adults; Wayne State University Institute of Gerontology: Detroit, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, J. Housing and Saving in the United States; Social Science Electronic Publishing: Rochester, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Krit, A. Lifestyle Migration: Architecture and Kinship in the Case of the British in Spain; University College: London, UK; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Addae-Dapaah, K.; Juan, Q.S. Life satisfaction among elder households in public rental housing in Singapore. Health 2014, 6, 1057–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Paez, A.; Scott, D.; Potoglou, D.; Kanaroglou, P.; Newbold, K.B. Elder mobility: Demographic and spatial analysis of trip making in the Hamilton CMA, Canada. Urban Stud. 2007, 44, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazio, T.; Saraceno, C. Does cohabitation lead to weaker intergenerational bonds than marriage? A comparison between Italy and the United Kingdom. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 29, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanger, D. Regional differences in household composition and family formation patterns in Vietnam. J. Comp. Fam. Stud. 2000, 31, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaymu, J.; Busque, M.A.; Légaré, J.; Décarie, Y.; Vézina, S.; Keefe, J. What will the family composition of older persons be like tomorrow? A comparison of Canada and France. Can. J. Aging 2010, 29, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.O. Family change and support of elder in Asia: What do we know? Asia-Pac. Popul. J. 1992, 7, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knodel, J.; Chayovan, N. Family support and living arrangements of Thai elders. Asia-Pac. Popul. J. 1997, 12, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Williamson, J.B.; Shen, C.; Yang, Y. Which pension model holds the most promise for China: A funded defined contribution scheme, a notional defined contribution scheme or a universal social pension? Benefits 2009, 17, 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Akihiro, H.; Iwai, K. Factors affecting choice of mode of sitting and sleeping by inhabitants of public housing. J. Hum. Ergol. 1976, 5, 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, M.A.; Wilson, V.F. To move or not to move? Factors influencing the housing choice of elder persons. J. Hous. Elders 2010, 10, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, S.-M. Housing preferences in a transitional housing system: The case of Beijing, China. Environ. Plan. A 2004, 36, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, S.-M. Socio-economic differentials and stated housing preferences in Guangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y. Research on the influence factors of elder pension mode selection. China Public Health 2003, 19, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.; Gu, S.; Krause, N. Social support among the aged in Wuhan, China. Asia-Pac. Popul. J. 1992, 7, 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, F.; Giles, J.; O’Keefe, P.; Wang, D. The Elderly and Old Age Support in Rural China: Challenges and Prospects; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, N. A Study of the option of the elderly on long-term care modes and influencing factors. Popul. J. 2014, 36, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Tan, Y. Behavior and factors influencing intergenerational household cohabitation/separation among urban Chinese citizens: A case study from Chengdu. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2015, 70, 1296–1312. [Google Scholar]

- Pingle, J.F. Welfare, intergenerational cohabitation penalties, and single mothers’ employment. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2005, 3, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Pei, R.; Qu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Z.; Yan, W.; Sun, X.; Sun, T.; Li, L. Urban-rural differences in factors associated with willingness to receive eldercare among the elderly: A cross-sectional survey in China. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e020225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Yang, G.; Hu, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, K.; Guang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xu, S.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y.; et al. The alienation of affection toward parents and influential factors in Chinese left-behind children. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 39, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Clark, W.A. Housing tenure choice in transitional urban China: A multilevel analysis. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.M. The housing market and tenure decisions in Chinese cities: A multivariate analysis of the case of Guangzhou. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer-Sánchez, V.; López-Martínez, G.; Molina-Moreno, V.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J. The role of women in a family economy. A bibliometric analysis in contexts of poverty. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, M.R.; Santor, E. Family values: Ownership structure, performance and capital structure of Canadian firms. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 2423–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age | Elder Live with Married Children | Ratio (%) | Elder Live with Unmarried Children | Ratio (%) | Elder Live with Grandchildren | Ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 25 | 1.01 | 92 | 3.73 | 1 | 0.04 |

| 25–34 | 354 | 14.36 | 192 | 7.79 | 6 | 0.24 |

| 35–44 | 303 | 12.29 | 55 | 2.23 | 91 | 3.69 |

| 45–54 | 271 | 10.99 | 42 | 1.70 | 84 | 3.41 |

| 55–64 | 183 | 7.42 | 37 | 1.50 | 108 | 4.38 |

| 65–74 | 187 | 7.59 | 31 | 1.26 | 181 | 7.34 |

| 75–84 | 95 | 3.85 | 24 | 0.97 | 85 | 3.45 |

| 85< | 6 | 0.24 | 3 | 0.12 | 9 | 0.37 |

| District | One Elder | Two Elders | More Than Two Elders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jinjiang | −10.94 | −6.97 | −0.17 |

| Qingyan | −11.24 | −9.04 | −0.10 |

| Jinniu | −7.56 | −5.37 | −0.07 |

| Wuhou | −12.52 | −9.37 | −0.11 |

| Chenghua | −9.40 | −7.19 | −0.08 |

| Financial Support | Daily Care Support | Emotional Support |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate house | In case of emergency | Fear of loneliness |

| Save costs | Doing the housework | Enjoyment of living with a big family |

| Poor health | Care of grandchildren |

| Factors | Mean | Standard Deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate house | 2.136 | 1.343 | 1–5 |

| Save costs | 2.796 | 1.442 | 1–5 |

| In case of emergency | 2.259 | 1.486 | 1–5 |

| Doing the housework | 1.845 | 1.367 | 1–5 |

| Poor health | 2.475 | 1.062 | 1–5 |

| Fear of loneliness | 2.562 | 1.604 | 1–5 |

| Enjoyment of living with a big family | 2.303 | 1.436 | 1–5 |

| Care of grandchildren | 2.505 | 1.463 | 1–5 |

| Variables | Elderly with Grandchildren | Elderly with Unmarried Children | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Sig. | S.E. | Exp (B) | B | Sig. | S.E. | Exp (B) | |

| Inadequate house | −0.861 | *** | 0.159 | 0.423 | 0.612 | *** | 0.148 | 0.542 |

| Save costs | 0.346 | * | 0.177 | 0.708 | 0.717 | *** | 0.160 | 2.049 |

| In case of emergency | −0.518 | *** | 0.132 | 0.595 | 0.221 | * | 0.121 | 0.802 |

| Enjoyment of living with a big family | −0.376 | ** | 0.155 | 0.686 | ||||

| Doing the housework | 1.087 | *** | 0.193 | 2.966 | ||||

| Fear of loneliness | 0.600 | *** | 0.141 | 0.549 | −0.300 | ** | 0.128 | 0.740 |

| Care of grandchildren | 0.471 | *** | 0.156 | 0.624 | ||||

| Poor health | 0.418 | *** | 0.134 | 0.658 | 0.239 | * | 0.127 | 0.787 |

| Constant | 7.66 | *** | 1.119 | 1.593 | *** | 1.001 | ||

| −2 log likelihood | 530.137 | |||||||

| Chi-square | 407.54 | |||||||

| Df | 16 | |||||||

| Significance | 0.000 | |||||||

| Nagelkerke | 0.655 | |||||||

| McFadden | 0.435 | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Yu, H. Intergenerational Factors Influencing Household Cohabitation in Urban China: Chengdu. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084289

Wang M, Yang Y, Liu M, Yu H. Intergenerational Factors Influencing Household Cohabitation in Urban China: Chengdu. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084289

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Meimei, Yongchun Yang, Mengqin Liu, and Huailiang Yu. 2021. "Intergenerational Factors Influencing Household Cohabitation in Urban China: Chengdu" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084289

APA StyleWang, M., Yang, Y., Liu, M., & Yu, H. (2021). Intergenerational Factors Influencing Household Cohabitation in Urban China: Chengdu. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4289. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084289