Perception and Demands of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women Regarding Their Role as Participants in Environmental Research Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

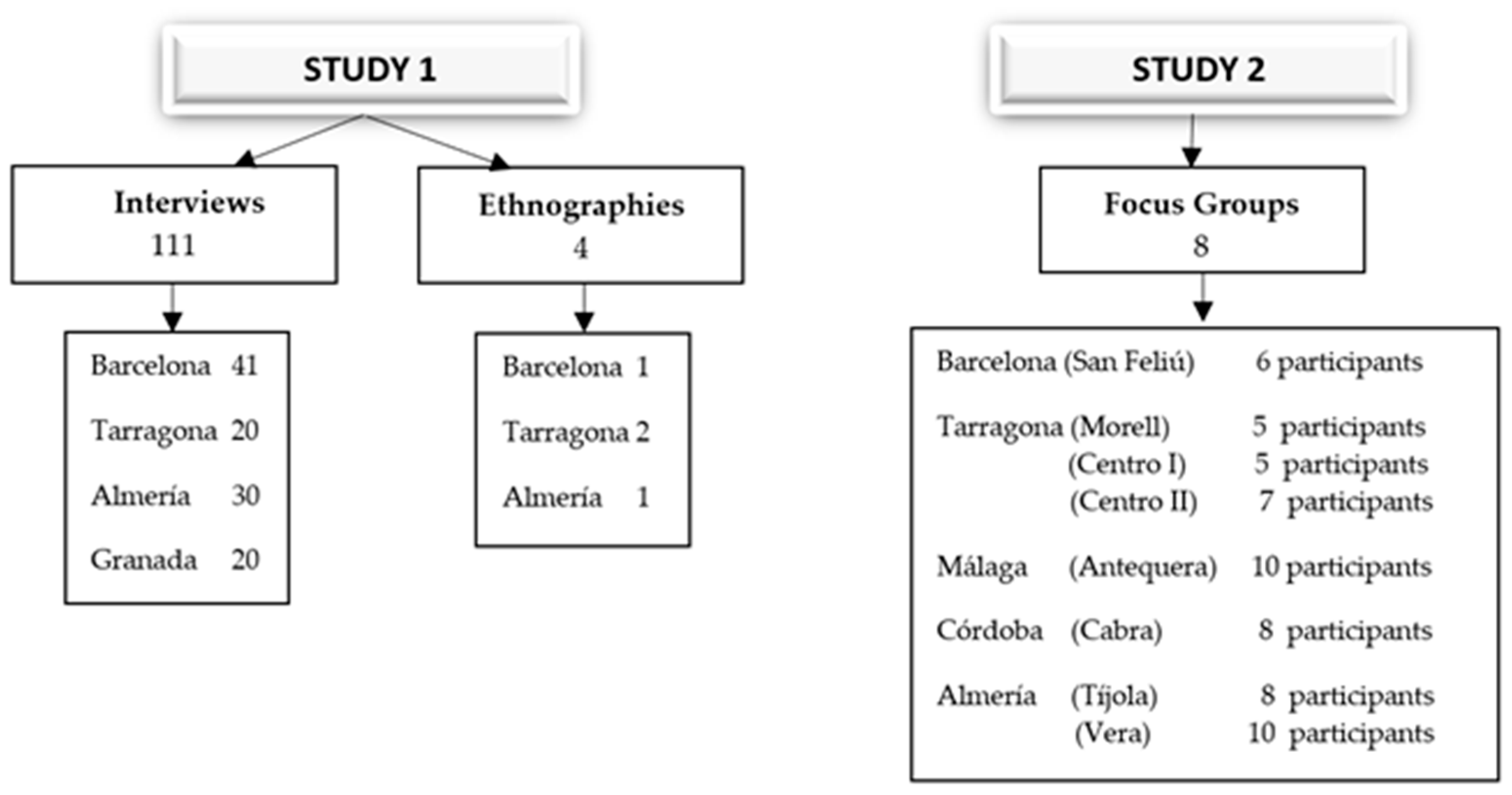

2.1. Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection and Fieldwork Instruments

2.3. Data Categorization and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Research Is of Interest to Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women

“No, to add that it seems to me that it’s one of the very important issues and many studies are needed, and this issue needs to be taken seriously because it’s fundamental. Food is basic”.(a 37-year-old breastfeeding mother who is an administrative assistant)

“And I think what is lacking is more studies, that is, more studies to know how these substances can harm us in the long run. But it is true that I believe we are quite helpless”.(a 42-year-old breastfeeding mother who is a teacher)

“No, I haven’t felt uncomfortable, I liked it, it’s always good to be informed and have knowledge. Now, if they tell you... well, now I’m going to get sick from this, what can I do? It’s always good to be informed [...], it’s more interesting than I expected. Really. Yes, it’s an interesting subject”.(a 33-year-old pregnant woman who is a salesperson)

“I just don’t know to what extent... it can be fixed. Because really, you’re not telling me, “the beach squid...” we don’t know if it is the beach squid or the fruit that comes from certain countries. What fruit?... Is it seasonal?... Strawberries? It’s a bit ambiguous. I think we need to take a closer look. Where it comes from and how it can be channelled. And the producers, I understand, have to be honest about the products’ origins. Nowadays, we know. We know the origin. At my work, in the workers’ restaurant, we know the origin of the products, whether they are first, second, third or fourth rate...”(a 39-year-old pregnant woman who is a management secretary)

“I don’t trust the market, because there are a lot of harmful things and they don’t put any kind of veto or anything”.“I do, I do trust it, you see...”“I solve it by looking at the labels, before I didn’t, but now I do look at what I buy [...] I see if there is anything I don’t know on the labels... When I start to see E-133, E-124, and more and more E’s ... I leave it...”“Having the information is important... because they trick you. I have a nephew who is now 12 years old and he was diagnosed with obesity and told not to drink packaged juices because perhaps on the label it says no added sugars, 22 calories, for example, and you think, look! Well, it seems okay... but that’s not really what they sell you...”“Yes, yes, or perhaps they tell you it’s per hundred grams, or per… I don’t know what.... And it seems low but afterwards!!!”(all from a discussion group, Tarragona)

3.2. The Need for Extensive Information on the Research Subject

“Well, what a bad business, ha ha... sounds very dangerous given the little information we have, for example, this “persistent” thing, and what foods have these “persistents”, how do we know?... Well, I don’t know, maybe the greengrocer’s where I sometimes shop for me, because for my son I go more for organic, but for me, I tell you, we do a fifty-fifty, one day I go to the market and buy the fruit, but who knows, how do I know? And if it’s controlled, shouldn’t it have a label for the user to decide? It’s just that, from what you’re saying, it sounds very ‘heavy’...”(a 39-year-old pregnant woman who is a nurse)

“Yes, I’ve heard something about it, because I’ve heard about the relationship between certain substances and infertility, which seems to be that [...] I’ve heard of a study showing that men are now more infertile than they were 40–50 years ago, and they blamed it on food, so I have heard a little in truth”.(a 29-year-old pregnant woman who is an instructor)

“ I think it’s true that there are a lot of foods that aren’t desirable, it’s also true that today’s regulations, the legislation, I think has changed a lot and the whole issue is quite controlled... at the phytosanitary level, fertilizers, etc. At least in Europe, that’s why I tell you, I trust Europe, not the rest of the world, and that there are no substances so, many certificates are required that you are not adding heavy metals to the products you sell etc. So I think something will come, it’s clear but, above all, at the pesticide level, but well, I think the minimum and I think our situation today is much better than what existed 40 years ago, I don’t know, the people say, ‘Before it was better and you ate a lot healthier’ Well, if your grandmother had an vegetable plot, maybe, but if not, no, even grandma knows what she puts on it, because nowadays you go to the villages, too, and people do terrible things, they put on products to remove the weeds “Mistol”, and a lot of things that they don’t know how to handle, for me that makes me more afraid than in more industrial production, so what people say, that today we are worse off than quite a few years ago is not true because there were very dangerous fertilizers and phytosanitary products that are now very prohibited, so I believe that in the end there will be things, there are also many degenerative diseases that arise, cancer etc. In the end, our life is very long and there has to be these kinds of things.”(a 34-year-old pregnant woman who is an agricultural engineer)

“It could be, he he he (laughs), perhaps it will make me look more at the label, it could be. Equally, it might not? I don’t know, I don’t know. I just tell you, maybe because of the pregnancy issue, I don’t want to, but because, I tell you, because the people say, don’t eat this! Don’t eat that! And hey, this yes you can eat! This causes you to, look, I eat what I’ve always eaten and that’s that. So, maybe, perhaps later, when I have the child, if I can do more, let’s see, this thing, what’s in it. That yes, well, because now I have my son, it’s going to be another story. But for me, what I eat is the same to me”.(a 39-year-old pregnant woman who is a lawyer)

“That’s what you have to think about, because if I’m eating plastic and I’m breastfeeding her, I’m passing on the plastic to her in some way and there isn’t much information about it, either. The information is like that, rough. In the sea, there is microplastic in the fish. The fish eat it, then, if you eat the fish, obviously you take in part of it, but there is no more information, and that’s how it is, and you stop to think and you say well, this in the long term, either my kidney or my bladder or my intestine at some point will say enough”.(a 37-year-old breastfeeding mother who is a businesswoman)

“I’ve been told this by my sisters-in-law, for the previous pregnancy. They say, ‘Avoid ham; if you can avoid it, avoid it.’ During the pregnancy, but, I mean, the doctors haven’t told me that, eh? That I shouldn’t eat... I haven’t been told”.(a 30-year-old pregnant woman who is unemployed)

3.3. Proposals during the Research and Shared Decision-Making

“Totally, it totally has an influence. I, for me, it has a direct influence, because the plants, from the rain, the water that falls, with the contaminated land, are fed from there. And animals that eat contaminated plants, or eat, well, everything... the water, everything, everything, the nitrates, everything that is in the soil, then everything is going to end up in the plant. And we eat all that. So, I do think it affects us. And here in Tarragona, especially. And besides, we don’t know what we’re breathing. I think it affects a lot [...] I had a vegetable garden at home, an urban garden, but I stopped doing it, because I say “I live here, in Ramon y Cajal, and I think I’m eating worse than if I go shopping at the greengrocer’s”, because here there are cars all day long. And, in the end, if I’m wiping away the dirt and that black stuff from the pollution comes out, then that same black stuff has been eaten by the plant. And I stopped doing it, in fact, for that reason. You do not trust the environment”.(a 32-year-old pregnant woman who is self-employed)

Moderator: “And how would you advise us, what would you say to us, having done this research? If you had to say, well, what is it that you want us to be able to say, what would you wish for?”Participant: “That you make things easier for us, right? That’s what I was saying. If I go to the store, I’m calmer, to say “Good heavens, what I’m buying, I don’t have to look at it and then look again, I don’t have to look at what it costs...”, because there are products that are very ecological, very healthy and such, but then they also cost a lot more money, right? And, sometimes, you can and, sometimes, you can’t. Well, make these two things easier”.(a 38-year-old breastfeeding mother who is a teacher)

“I think there are solutions, such as trying to consume on an ecological level, so look for companies that work with organic products, or look for livestock cooperatives that work at an ecological level. It seems complicated, but... it is difficult yet not so difficult, because I know of people who only buy organic, organic soap, organic shampoo, which obviously means they have certain resources, what we talked about before, money, it is clear that it is not... but it is possible, having in the house less plastic utensils and more cast iron, glass, but of course, it is a very severe change of mindset”.(a 29-year-old pregnant mother who is an instructor)

“Of course, given that I had no idea about any of this, and I’m caught again, I can’t say anything else, because I have to process it myself, and know and realize and try to be more careful when buying and where to buy it, if it’s packaged or if it’s loose, and control a little more because they had no idea”.(a 30-year-old pregnant woman who is an office worker)

“Pfff.... At the collective level, it would be to raise awareness among all those who provide us with food, livestock, the... well, in the end, do you know what’s going on? Because in society we are so irresponsible, we are destroying ourselves, in that sense, because if we looked after the environment (...), if the people who have to provide us with food, instead of using pesticides, they used natural fertilizers, if they became more aware, it would surely change. But since it isn’t like that, they need things to come out fast, to make the greatest quantity to be able to make a profit, and we don’t achieve this. (...) and on an individual level, I think it’s looking for things that are more natural, but it’s complicated. You have to know that it is from a person who is growing their vegetables with natural fertilizers, that they don’t put anything else on, that they also normally have the natural ones that don’t have additives, very soon they go bad, it is a little like trying to look, that you don’t always have the ability, nor do you have it at hand.”(a 38-year-old pregnant woman who is a nursing auxiliary)

3.4. Availability to the Women of the Information Coming from the Research

“I always had notions of what is healthy, more or less, because in my house my parents have instructed us a lot about such a diet, how it is, the Mediterranean diet and all that. Now during the pregnancy, I am aware of the foods that are harmful, because look, it all started because you gave us the study that you did in Antequera hospital, she passed us the information, I read it and I said: <Wow, this I really have to look at>. And then you start looking at it”.(a 35-year-old pregnant woman who is a dentist)

“And especially if you stop to read your information and start thinking about pollution above all in the water, which says we’re eating plastics, and you’re surprised like: how is it I’m eating plastic?”.(a 32-years-old breastfeeding mother who is a psychologist)

“It seems that we are condemned to disease (....) to see what comes out in the study, because I think we are all concerned with the chemical issue, even if we continue with the same habits, because you can improve the habits and go shopping in ecological shops, but you can’t buy everything organic and if you live in Barcelona, you have chemicals everywhere. To see what you come out with, because it’s frightening, now you also hear a lot about cancer lately, which I think has a lot to do with food and food production habits”.(a 38-year-old breastfeeding mother who is a social worker)

“What you carry, you can pass on to your baby, what circulates through you when he is in-utero is connected to you, to your circulatory system, and if you breastfeed, what you’re consuming is being passed to him. If you consume stimulant drinks, you pass on the stimulant drinks to him, if you consume things with a lot... that are very gassy, you pass the gases to him, yes”.(a 39-year-old pregnant woman who is a nursing auxiliary)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grimalt, J.O.; Carrizo, D.; Gari, M.; Font-Ribera, L.; Ribas-Fito, N.; Torrent, M.; Sunyer, J. An evaluation of the sexual differences in the accumulation of organochlorine compounds in children at birth and at the age of 4 years. Environ. Res. 2010, 110, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gascon, M.; Vrijheid, M.; Martínez, D.; Ballester, F.; Basterrechea, M.; Blarduni, E.; Esplugues, A.; Vizcaino, E.; Grimalt, J.O.; Morales, E.; et al. Pre-Natal exposure to dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene and infant lower respiratory tract infections and wheeze. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 39, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadó, L.; Arrebola, J.P.; Fontalba, A.; Muñoz, A. Adverse effects of hexachlorobenzene exposure in children and adolescents. Environ. Res. 2019, 176, 108421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, M.; Borrell, C.; Copete, J.L. Commentary: Theory in the fabric of evidence on the health effects of inequalities in income distribution. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Andersen, H.; Vinggaard, A.M.; Høj Rasmussen, T.; Gjermandsen, I.M.; Cecilie Bonefeld-Jørgensen, E. Effects of currently used pesticides in assays for estrogenicity, androgenicity, and aromatase activity in vitro. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2002, 179, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrebola, J.P.; Cuellar, M.; Claure, E.; Quevedo, M.; Antelo, S.R.; Mutch, E.; Ramirez, E.; Fernandez, M.F.; Olea, N.; Mercado, L.A. Concentrations of organochlorine pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyls in human serum and adipose tissue from Bolivia. Environ. Res. 2012, 112, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrebola, J.P.; Fernandez, M.F.; Porta, M.; Rosell, J.; de la Ossa, R.M.; Olea, N.; Martin-Olmedo, P. Multivariate models to predict human adipose tissue PCB concentrations in Southern Spain. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 705–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrebola, J.P.; Martin-Olmedo, P.; Fernandez, M.F.; Sanchez-Cantalejo, E.; Jimenez-Rios, J.A.; Torne, P.; Porta, M.; Olea, N. Predictors of concentrations of hexachlorobenzene in human adipose tissue: A multivariate analysis by gender in Southern Spain. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustieles, V.; Arrebola, J.P. How polluted is your fat? What the study of adipose tissue can contribute to environmental epidemiology. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2020, 74, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrebola, J.P.; Cuellar, M.; Bonde, J.P.; González-Alzaga, B.; Mercado, L.A. Associations of maternal o,p′-DDT and p,p′-DDE levels with birth outcomes in a Bolivian cohort. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikołajewska, K.; Stragierowicz, J.; Gromadzińska, J. Bisphenol A—Application, sources of exposure and potential risks in infants, children and pregnant women. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2015, 28, 209–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Cheng, H.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, C.; Di Narzo, A.; Yu, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, Y.; et al. Prenatal Exposure to Ambient Air Multi-Pollutant Mixture Significantly Impairs Intrauterine Fetal Development Trajectory. 2020. in press. Available online: https://assets.researchsquare.com/files/rs-14985/v1/manuscript.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Salmani, M.H.; Rezaie, Z.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Ehrampoush, M.H. Exposición al arsénico de los lactantes: Lactancia materna contaminada en el primer mes de nacimiento. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 6680–6684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, F. Arsênio, Cádmio, Chumbo E Mercúrio Em Leite Humano- Análise, Avaliação Da Exposição E Caracterização Do Risco de Lactentes; University of Brasilia: Brasilia, Brasil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, J.P.; Lara, B.L.; Álvarez-Dardet, S.M. Estrés y competencia parental: Un estudio con madres y padres trabajadores. Suma Psicologica 2010, 17, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Padilla, J.; Ayala-Nunes, L.; Hidalgo, M.V.; Nunes, C.; Lemos, I.; Menéndez, S. Parenting and stress: A study with Spanish and Portuguese at-risk families. Int. Soc. Work 2017, 60, 1001–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, B.; Parker, G. Possible determinants, correlates and consequences of high levels of anxiety in primiparous mothers. Psychol. Med. 1986, 16, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoursandi, M.; Vakilian, K.; Torabi Goudarzi, M.; Abdi, M. Childbirth preparation using behavioral-cognitive skill in childbirth outcomes of primiparous women. J. Babol. Univ. Med. Sci. 2013, 15, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guardino, C.M.; Schetter, C.D. Coping During Pregnancy. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 8, 70–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lomnitz, L. Redes Sociales, Cultura Y Poder. Ensayos De Antropología Lationamericana; Porrúa/Flacso: México City, México, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Rozin, P.; Fischler, C.; Imada, S.; Sarubin, A.; Wrzesniewski, A. Attitudes to food and the role of food in life in the USA, Japan, Flemish Belgium and France: Possible implications for the diet-health debate. Appetite 1999, 33, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zande, I.S.E.; van der Graaf, R.; Oudijk, M.A.; van Delden, J.J.M. Vulnerability of pregnant women in clinical research. J. Med. Ethics 2017, 43, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krubiner, C.B.; Faden, R.R. Pregnant women should not be categorised as a “vulnerable population” in biomedical research studies: Ending a vicious cycle of “vulnerability”. J. Med Ethics 2017, 43, 664–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrilla Latas, M. Ética Para Una Investigación Inclusiva. Rev. Educ. Incl. 2010, 3, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, M.J. Las Culturas del Nacimiento; En la Universitat Rovira i Virgili: Catalonian, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez-Rodríguez, M.I. Del enfoque de riesgo al enfoque fisiológico en la atención al embarazo, parto y puerperio. Aportaciones desde una etnografía feminista. In Antropología, Género, Salud Y Atención; Esteban, M.L., Comelles, J.M., Mintegui, C.D., Eds.; Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 209–231. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Chávarri, A.; Abt-Sacks, A.; Orrego, C.; Perestelo-Pérez, L. El papel de la comunicación escrita en el empoderamiento en salud: Un estudio cualitativo. Panacea 2016, 17, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, A.; Joshi, A. An Overview of Chronic Disease Models: A Systematic Literature Review. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krucien, N.; le Vaillant, M.; Pelletier-Fleury, N. What are the patients’ preferences for the Chronic Care Model? An application to the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 2536–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Women. Annual Report 2015/2016. 2016. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/annual%20report/attachments/sections/library/un-women-annual-report-2015-2016-en.pdf?la=en&vs=3016 (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS). Estrategia Mundial para la Salud de la Mujer, el Niño y el Adolescente (2016–2030). 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/328740/A72_30-sp.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Gobierno de España Plan de Acción para La implementación de la Agenda 2030 Hacia una Estrategia española de Desarrollo Sostenible. 2019; pp. 1–164. Available online: http://www.exteriores.gob.es/portal/es/saladeprensa/multimedia/publicaciones/documents/plan%20de%20accion%20para%20la%20implementacion%20de%20la%20agenda%202030.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Anderson, R.M.; Funnell, M.M. Patient empowerment: Reflections on the challenge of fostering the adoption of a new paradigm. Patient Educ. Couns. 2005, 57, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Patients’ Forum. EPF Background Brief: Patient Empowerment. Strong Patient’s Voice Drive Better Health Eur. 2015, 15, 12. Available online: https://www.eu-patient.eu/policy/campaign/PatientsprescribE/ (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Bravo, P.; Edwards, A.; Barr, P.J.; Scholl, I.; Elwyn, G.; McAllister, M. Conceptualising patient empowerment: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamundi Barros, P. Empoderamiento En La Mujer Embarazada Frente a Educación Maternal: Ensayo Clínico De Superioridad; Universidade da Coruña: Galicia, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, M. Empowerment and health promotion. Red. Salud. 2009, 41, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, P.; Hammersley, M. Ethnography and Participant Observation. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 248–261. [Google Scholar]

- Ruíz, J.I. Metodología De La Investigación Cualitativa; Universidad de Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, H.; Díaz de Rada, A. La lógica de la investigación etnográfica. Un modelo de trabajo para etnógrafos de escuela; Trotta: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; Sage publications: Szende Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 1483300862. [Google Scholar]

- Fàbregas, M.; Fabrellas, N.; Larrea-Killinger, C. Fuentes de información alimentaria que utilizan las mujeres embarazadas y lactantes. Matronas Profesión 2019, 20, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, A.; Fontalba-Navas, A.; Arrebola, J.P.; Larrea-Killinger, C. Trust and distrust in relation to food risks in Spain: An approach to the socio-cultural representations of pregnant and breastfeeding women through the technique of free listing. Appetite 2019, 142, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafra, E.; Company, M.; Casadó, L. Escenarios urbanos y subjetividades en la construcción de discursos y prácticas sobre cuerpo, género y alimentación: Una etnografía alimentaria sobre mujeres embarazadas y lactantes en España en: In Consumos Alimentares em Cenários Urbanos; Ferre, D.M.N.F.A.R., Ed.; Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020; Volume 11, pp. 299–328. ISBN 9786162833052. [Google Scholar]

- Larrea-killinger, C.; Muñoz, A.; Begueria, A.; Mascaró-pons, J. Body representations of internal pollution: The risk perception of the circulation of environmental contaminants in pregnant and breastfeeding women in Spain. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Boixareu, R.M. De la antropología filosófica a la antropología de la salud; Herder: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- van Dijk, T. El discurso como interacción social; Gedisa: Barcelona, Spain, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet, A.; Gotman, A. L’enquête et ses méthodes: L’entretien; Armand Colin: Paris, French, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- RICKHAM, P. Human experimentation. Code of ethics of the world medical association. Declaration of Helsinki. Br. Med. J. 1964, 2, 177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Borgatti, P.; Everett, M.G.; Freeman, L.C. UCINET IV: Network Analysis Software; User’s Guide; Analytic Technology: Harvard, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Spradley, J.P. The Ethnographic Interview; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, D.A. Lay discourses and beliefs related to food risks: An Australian perspective. Sociol. Health Illn. 2005, 27, 448–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, D. Medicine as Culture: Illness, Disease and the Body; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Arrebola, J.; Killiger, C.; Fontalba, A.; Fábregas, M.; Muñoz, A.; Company-Morales, M.; Zafra, E.; Casadó, L. Contaminantes Químicos Ambientales Presentes en Los Alimentos. Guía De Recomendación a Mujeres Embarazadas Y Lactantes. Available online: http://www.ub.edu/toxicbody/es/guia/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- Bourdieu, P. El Oficio De Científico. Ciencia De La Ciencia Y Reflexividad.; Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper, A. Ética Y Moral: Una Introducción a La Filosofía Práctica; Crítica: Barcelona, Spain, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cortina A, N.E.M. Ética; Ediciones AKAL: Madrid, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wild, V.; Pratt, B. Health incentive research and social justice: Does the risk of long-term harms to systematically disadvantaged groups bear consideration? J. Med. Ethics 2017, 43, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Törnblom, K.Y.; Vermunt, R. Distributive and Procedural Justice: Research and Social Applications; Ashgate: Burlington, NC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Sandel, M. Justice. What’s the Right Thing to Do? Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Peñaranda, F. Salud Pública, justicia social e investigación cualitativa: Hacia una investigación por principios. Fac. Nac. Salud. Pública. 2015, 33, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macklin, R. Enrolling pregnant women in biomedical research. Lancet 2010, 375, 632–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, J.; Barclay, L.; Cooke, M. The Concerns and Interests of Expectant and New Parents: Assessing Learning Needs. J. Perinat. Educ. 2006, 15, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyerly, A.D.; Mitchell, L.M.; Armstrong, E.M.; Harris, L.H.; Kukla, R.; Kuppermann, M.; Little, M.O. Risks, values, and decision-making surrounding pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2010, 109, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M. Los programas de educación maternal y el empoderamiento de las mujeres. MUSAS: Revista Investig. Mujer Salud. Soc. 2017, 2, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio-Cantalejo, I.M.; Simón-Lorda, P.; Hospital, F.; De, V.; Granada, N. Problemas éticos de la investigación cualitativa. Med. Clin. (Barc.) 2006, 126, 418–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, C.P.; Pinedo, I.A.; Grandes, G.; Cifuentes, M.E.; Inda, I.G. Necesidades percibidas por las mujeres respecto a su maternidad. Estudio cualitativo para el rediseño de la educación maternal. Atención Primaria 2016, 48, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Begueria, A.; Larrea, C.; Muñoz, A.; Zafra, E.; Mascaró-Pons, J.; Porta, M. Social discourse concerning pollution and contamination in Spain: Analysis of online comments by digital press readers. Contrib. Sci. 2015, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pumarega, J.; Larrea, C.; Muñoz, A.; Pallarés, N.; Gasull, M.; Rodriguez, G.; Jariod, M.; Porta, M. Citizens´ perceptions of the presence and health risks of synthetic chemicals in food: Results of an online survey in Spain. Gac. Sanit. 2017, 31, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, H.Z.; Bike, D.H.; Ojeda, L.; Johnson, A.; Rosales, R.; Flores, L.Y. Qualitative Research as Social Justice Practice with Culturally Diverse Populations. J. Soc. Action Couns. Psychol. 2013, 5, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponterotto, J.G.; Mathew, J.T.; Raughley, B. The Value of Mixed Methods Designs to Social Justice Research in Counseling and Psychology. J. Soc. Action Couns. Psychol. 2013, 5, 42–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacimientos Por Tipo de Parto, Tiempo de Gestación y Grupo de Edad de La Madre. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Datos.htm?path=/t20/e301/nacim/a2015/l0/&file=01011.px (accessed on 23 March 2021).

| Participants 173 | 84 | 89 |

|---|---|---|

| Age range | ||

| Age-20–29 | 12 | 16 |

| Age-30–39 | 65 | 64 |

| Age-40+ | 7 | 9 |

| Education Level | ||

| Primary | 6 | 4 |

| Secondary | 27 | 29 |

| Higher | 51 | 56 |

| Number of children | ||

| 1 Child | 47 | 54 |

| 2 children | 29 | 31 |

| 3 Children or + | 8 | 4 |

| Province | ||

| Almería | 24 | 24 |

| Barcelona | 25 | 32 |

| Córdoba | 5 | 3 |

| Granada | 9 | 11 |

| Málaga | 6 | 4 |

| Tarragona | 16 | 14 |

| Autonomous Community | ||

| Andalucía | 44 | 42 |

| Cataluña | 41 | 46 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Company-Morales, M.; Zafra Aparici, E.; Casadó, L.; Alarcón Montenegro, C.; Arrebola, J.P. Perception and Demands of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women Regarding Their Role as Participants in Environmental Research Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084149

Company-Morales M, Zafra Aparici E, Casadó L, Alarcón Montenegro C, Arrebola JP. Perception and Demands of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women Regarding Their Role as Participants in Environmental Research Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084149

Chicago/Turabian StyleCompany-Morales, Miguel, Eva Zafra Aparici, Lina Casadó, Cristina Alarcón Montenegro, and Juan Pedro Arrebola. 2021. "Perception and Demands of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women Regarding Their Role as Participants in Environmental Research Studies" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084149

APA StyleCompany-Morales, M., Zafra Aparici, E., Casadó, L., Alarcón Montenegro, C., & Arrebola, J. P. (2021). Perception and Demands of Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women Regarding Their Role as Participants in Environmental Research Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084149