A Phenomenological Study of Mental Health Enhancement in Taekwondo Training: Application of Catharsis Theory

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Integrity of Study

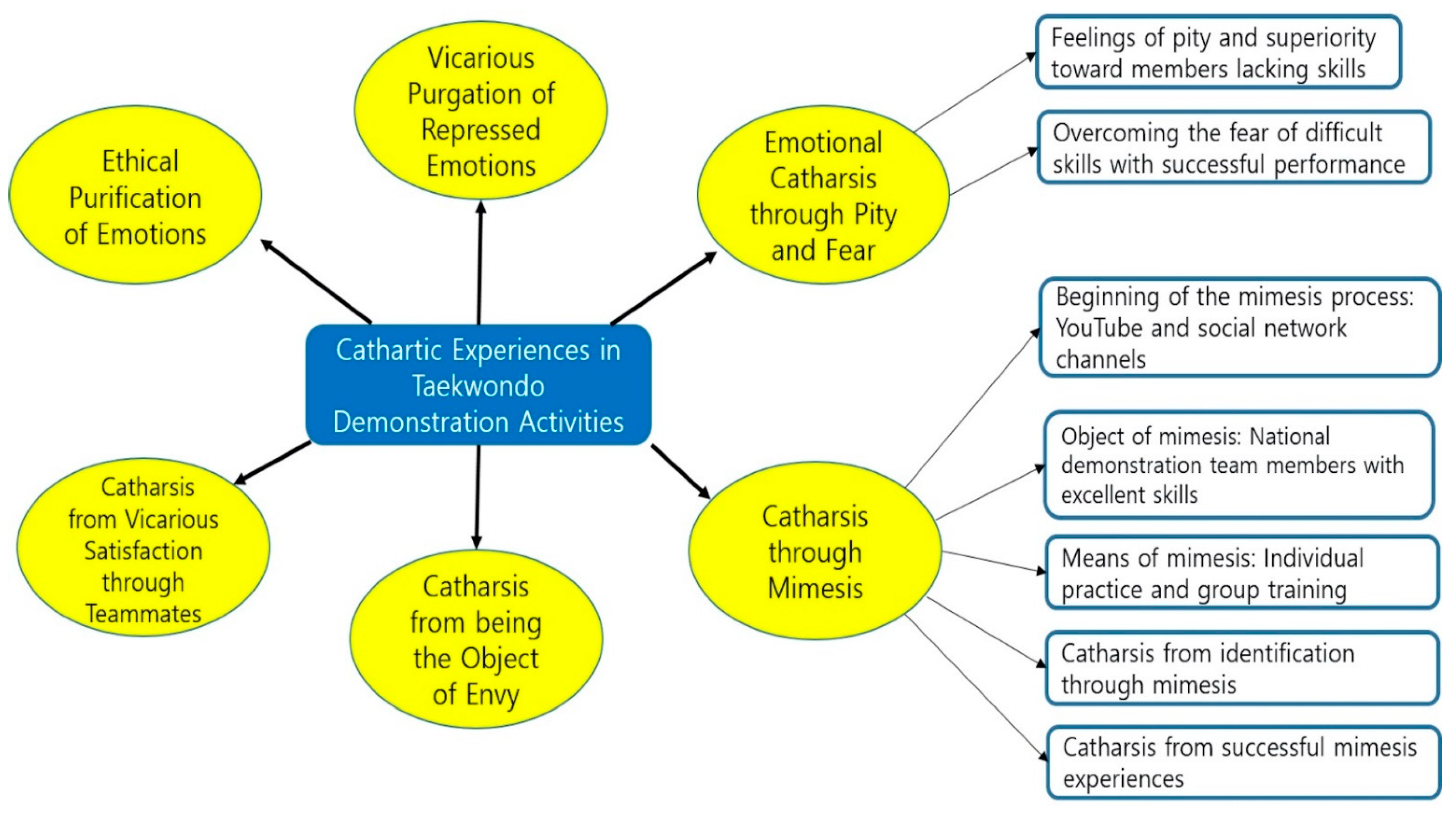

3. Result: Cathartic Experiences in Taekwondo Demonstration Activities

3.1. Vicarious Purgation of Repressed Emotions

“When I successfully perform a high-level Taekwondo skill, it feels like all the stress is blown away at once. When practicing an advanced skill, I forget everything else and only focus on that skill. Practicing Taekwondo demonstration is the only time I can relieve all my stress.”(Participant 1)

“When I participate in the demonstration team practice and sweat, it feels like the impurities in my mind are cleansed… When I sweat… Then with that sweat, I feel as if my anxiety and worries are removed from my mind… I really like those moments… Soaked in sweat, I feel that I am alive, and I like that feeling…”(Participant 2)

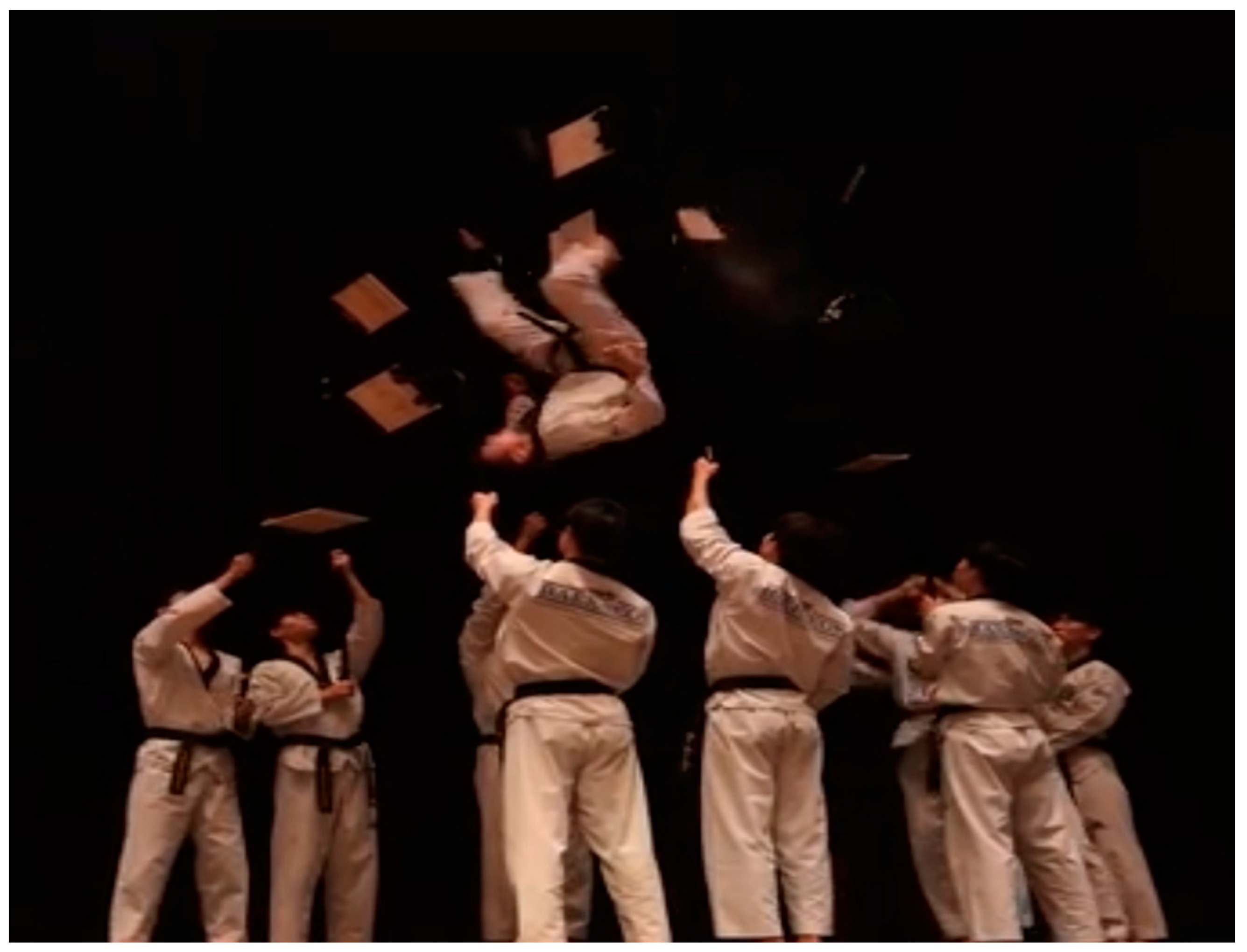

“Taekwondo demonstration shows are held in a very heated atmosphere. Strong energy is expressed in the form of music, dance, wood breaking demonstration, etc. It seems that a Taekwondo demonstration show is an outlet of youthful energy. During the show, I am the protagonist of the show, and it feels like good energy springs up inside me.”(Participant 12)

3.2. Emotional Catharsis through Pity and Fear

3.2.1. Feelings of Pity and Superiority toward Members Lacking Skills

“I feel sorry to see my teammates who lack some Taekwondo skills striving to acquire the skills. So, I help them master those skills. I also feel a sense of superiority when these less skilled members look at me demonstrating with envious eyes.”(Participant 11)

“Many of my teammates want to perform kicks and flips just as well as I do. When my teammates cheer for my demonstrations, I feel a sense of superiority for some reason.”(Participant 3)

3.2.2. Overcoming the Fear of Difficult Skills with Successful Performance

“At my first demonstration show in 2020, I was in charge of wood breaking with a 720° spinning kick. I practiced a lot before the performance. I succeeded in performing the skill during practice, but I was very worried about whether I could do well at the demonstration show. When my turn approached, I was overwhelmed by the fear of failure. However, I took a deep breath, gave a shout for concentration, and successfully smashed the board. The joy I felt at the moment was something that I had never experienced before.”(Participant 4)

“I usually demonstrate wood breaking with ten consecutive turning back round kicks. It takes speed to perform the skill, so the teamwork with the members holding the pine boards is very important. If you miss the right timing, the boards will not break. When I smash all the ten boards in a row, one by one, I feel an excitement that cannot be described with words. It feels amazing to hear the cheers of the audience after overcoming the moments of nervousness and fear.”(Participant 5)

3.3. Ethical Purification of Emotions

“At a demonstration contest, we engage in a very fierce competition with other teams. Each team does their best to win. This, however, does not mean that we want the opposing team to fail when they perform wood breaking or other skills. Instead of wanting the other teams to make mistakes, we need to win the competition by our own ability. After the competition is over, regardless of the result, we show respect to each other. I do think that members of the other teams are also my fellow Taekwondo demonstrators.”(Participant 9)

“In a sparring fight, we have a one-on-one physical fight with the opponent, but in a demonstration contest, it is the skills that each team demonstrates and the composition of their performances that determine the winner. That is why teamwork and harmony are important in a demonstration contest. So, at the end of the contest, a solid bond is formed among the teammates who practiced together for the demonstration. As we know that the demonstrators of other teams also worked hard to prepare for the contest, we can also cheer for them.”(Participant 8)

3.4. Catharsis through Mimesis

3.4.1. Beginning of the Mimesis Process: YouTube and Social Network Channels (Instagram, Facebook, etc.)

“These days, I look up Taekwondo demonstration a lot on YouTube. I try to identify the skills featured in demonstration videos and imitate the skills to master them.”(Participant 7)

“I am following famous Taekwondo athletes who have excellent wood breaking skills on Instagram and Facebook. I try to imitate their skills watching the demonstration videos posted on their Instagram account.”(Participant 6)

3.4.2. Object of Mimesis: National Demonstration Team Members with Excellent Skills

“Athlete 000 of the national demonstration team commands the best jump skill in Korea. I practice hard to imitate the skill. When I succeed in performing the skill of 000, I feel much excited that I can perform like him.”(Participant 4)

“I think Korea’s best consecutive kick demonstrator is 000. 000 is my role model. When I successfully perform the skill he demonstrates, I feel confident that I can perform like him, identifying myself with him.”(Participant 5)

3.4.3. Means of Mimesis: Individual Practice and Group Training

“I teach myself the wood breaking skill of 000 during my individual practice time. Since group training takes up a large portion of the demonstration team training, I personally take time for practicing the skill that I am going to demonstrate.”(Participant 12)

“I individually practice the wood breaking skills of my favorite Taekwondo athletes. When I show my teammates the skills I mastered through individual practice during group training, they compliment me and I feel flattered.”(Participant 1)

3.4.4. Catharsis from Identification through Mimesis

“When I practice to master the skills of Taekwondo athlete 000, who is my role model, I imagine that I became the athlete.”(Participant 2)

It feels great when my teammates see me practicing some skills and tell me that my moves remind them of those of Taekwondo athlete 000, who is my idol.(Participant 9)

3.4.5. Catharsis from Successful Mimesis Experiences

“During my performance, I successfully demonstrated the scissors kick skill of Taekwondo athlete 000 that I had practiced very hard. Listening to the applause and cheers of the crowd, I felt a quiver of joy.”(Participant 8)

“I mastered the high-level wood breaking with a flip kick skill of athlete 000 after practicing for a very long time. Finally, I had the opportunity to demonstrate that skill in a performance, and I gave a perfect demonstration though I was very nervous. It still makes me feel so happy to recall that success experience.”(Participant 10)

3.5. Catharsis from Vicarious Satisfaction through Teammates

“I am the leader of my team, and it seems like I feel the happiness and excitement that my teammates feel each time they successfully demonstrate skills. Especially, when they give a perfect demonstration of high-level skills, I really feel thrilled. I become sensitive to every move of my teammates, get excited by it, and during a demonstration show, I feel so united with all my teammates.”(Participant 4)

“In a demonstration performance held a while ago, 000 succeeded in performing the wood breaking with a flip kick that he practiced hard. At that time, I felt extremely happy as if I myself had succeeded in it.”(Participant 3)

3.6. Catharsis from Being the Object of Envy

“Not long ago, I performed at a demonstration show held to celebrate a Taekwondo competition. After the demonstration was over, children asked me to take pictures together. They said that my demonstration was great and that my skills were very cool. I felt catharsis in that I became the object of someone else’s envy.”(Participant 1)

“When I demonstrate Taekwondo skills, I feel like people are looking up at me. When I hear the cheers of the crowd during my performance, I feel like I have become a celebrity.”(Participant 5)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Piñeiro-Cossio, J.; Fernández-Martínez, A.; Nuviala, A.; Pérez-Ordás, R. Psychological Wellbeing in Physical Education and School Sports: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, M.; Reimers, A.K.; Demetriou, Y. Leisure Time Sports Activities and Life Satisfaction: Deeper Insights Based on a Representative Survey from Germany. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. A Cathartic Function of Sport: A Philosophical Approach. J. Korean Phys. Educ. 2000, 39, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, J.C. The Logical Exploration About the Taekwondo History Discourse. J. Korean Phys. Educ. 2016, 55, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.J. The Moderating Effects of Taekwondo Training Against Life Stress on Mental Health. J. Korean Phys. Educ. 1996, 35, 300–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.H.; Choi, E.G. Taekwondo Trainees’ Physical Self Concept. J. Korean Phys. Educ. 2005, 44, 231–239. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, T.H. Effect of Taekwondo Program for Character. Taekwondo J. Kukkiwon 2015, 6, 71–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.G.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, J.H. The Relationship between Children’s Etiquette and Self-Control during Taekwondo Practice. J. Korean Phys. Educ. 2003, 42, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Yeun, J.H. Value of Character in Taekwondo Training. Taekwondo J. Kukkiwon 2013, 4, 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, E.J.; Yoo, K.G. The Effects of Etiquette Execution of Elementary School Students Attending Taekwondo Academy Affecting their Emotions. J. Korean Phys. Educ. 2004, 43, 667–674. [Google Scholar]

- Kadri, A.; Slimani, M.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Tod, D.; Azaiez, F. Effect of Taekwondo Practice on Cognitive Function in Adolescents with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, H.-T.; Cho, S.-Y.; So, W.-Y. Taekwondo Training Improves Mood and Sociability in Children from Multicultural Families in South Korea: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, W.J. Educational Function Analysis of Taekwondo Class as Secondary School Physical Education Classes. Taekwondo J. Kukkiwon 2019, 10, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, B.G. Application of Taekwondo Spirit as a Means of Mental Education. Taekwondo J. Kukkiwon 2019, 10, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.Y. Understanding the Experience of Katharsis during Sports Activity of Soccer. Master’s Thesis, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, S.Y. A Study on Aristotle’s ‘Poet’ and Kant’s ‘Aesthetics’. J. Converg. Cult. Technol. 2016, 2, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.S. A Study of Practical Utility of Catharsis. J. Yonsei 1988, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kerry, D.S.; Armour, K.M. Sport Sciences and the Promise of Phenomenology: Philosophy, Method, and Insight. Null 2000, 52, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, S. The Significance of Human Movement: A Phenomenological Approach. In Sport and the Body: A Philosophical Symposium; Lea & Febiger: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1979; pp. 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, G.A. Existential Phenomenology: Emphasizing the Experience of the Athlete in Sport Psychology Research. Sport Psychol. 1996, 10, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón-Solanas, I.; Huércanos-Esparza, I.; Hamam-Alcober, N.; Vanceulebroeck, V.; Dehaes, S.; Kalkan, I.; Kömürcü, N.; Coelho, M.; Coelho, T.; Casa-Nova, A.; et al. Nursing Lecturers’ Perception and Experience of Teaching Cultural Competence: A European Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skillen, A. Sport: An Historical Phenomenology. Philosophy 1993, 68, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockey, J.; Collinson, J.A. Grasping the Phenomenology of Sporting Bodies. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2007, 42, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brymer, E.; Schweitzer, R. Phenomenology and the Extreme Sport Experience; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Chen, T.-L.; Lin, C.-J.; Liu, H.-K. (Jonathan) Preschool Teachers’ Perception of the Application of Information Communication Technology (ICT) in Taiwan. Sustainability 2018, 11, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocki, J.M.; Wearden, A.J. A critical evaluation of the use of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) in health psychology. Psychol. Health 2006, 21, 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Lee, H.-J. South Korean Nurses’ Experiences with Patient Care at a COVID-19-Designated Hospital: Growth after the Frontline Battle against an Infectious Disease Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, W.C.; Lee, S.H. A Phenomenological Study on Ethical Problems of Taekwondo Game Culture. J. Sport Leis. Stud. 2008, 34, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glesne, C. Becoming Qualitative Researchers: An Introduction; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. Case Study Research in Education: A Qualitative Appoach; Jossey-Bass Publischer: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B.L. Methods for the Social Sciences. In Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Steinkraus, W.E.; Van Kaam, A. Existential Foundations of Psychology. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 1967, 28, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.; Eppard, J. Van Kaam’s Method Revisited. Qual. Health Res. 1998, 8, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Poth, C.N. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bing, W.C.; Seok, J.I.; Kim, H.D. A Phenomenological Study on Experience of catharsis in Basketball Players of University 583 Club. J. Korean Soc. Phil. Sport Dance Martial 2009, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Solbakk, J.H. Catharsis and Moral Therapy II: An Aristotelian Account. Med. Health Care Philos. 2006, 9, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlenka, C. The Idea of Fairness: A General Ethical Concept or One Particular to Sports Ethics? J. Philos. Sport 2005, 32, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastad, D.N.; Segrave, J.O.; Pangrazi, R.; Petersen, G. Youth Sport Participation and Deviant Behavior. Sociol. Sport J. 1984, 1, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, P.N. Rene Girard and the Psychology of Mimesis. In Models of Desire; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Molin, R.; Palmer, S. Consent and Participation: Ethical Issues in the Treatment of Children in Out-of-Home Care. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2005, 75, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doob, L.W.; Sears, R.R. Factors Determining Substitute Behavior and the Overt Expression of Aggression. J. Abnorm. Soc. Psychol. 1939, 34, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meisiek, S. Which Catharsis Do They Mean? Aristotle, Moreno, Boal and Organization Theatre. Organ. Stud. 2004, 25, 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, L. Catharsis. In Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1962; Volume 93, p. 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, L. The Purgation Theory of Catharsis. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1973, 31, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, H.D. Mimesis and Catharsis Reexamined. J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1966, 24, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, L. Mimesis and Katharsis. Class. Philol. 1969, 64, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, C.B.; Scully, S. Pity, Fear, and Catharsis in Aristotle’s Poetics. Noûs 1992, 26, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskow, A. What Is Aesthetic Catharsis? J. Aesthet. Art Crit. 1983, 42, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, J.J. Cultural relativism. Blackwell Encycl. Sociol. 2007, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, M. The Story of an Ethnography: The Experience of Watching the 2002 World Cup in the Pub. Soccer Soc. 2006, 7, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, M.; Freud, S.; Breuer, J.; Bowlby, R.; Luckhurst, N. Studies in Hysteria. Mod. Lang. Stud. 2006, 36, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, J.; Miller, N.E.; Doob, L.W.; Mowrer, O.H.; Sears, R.R. Frustration and Aggression; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, A.H. Catharsis; American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 2006; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, L. Aggression: A Social Psychological Analysis; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1962; p. 361. [Google Scholar]

- Krahé, B. The Social Psychology of Aggression; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bushman, B.J. Does Venting Anger Feed or Extinguish the Flame? Catharsis, Rumination, Distraction, Anger, and Aggressive Responding. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.R.; Jeong, E.J.; Kim, J.W. How Do You Blow off Steam-The Impact of Therapeutic Catharsis Seeking, Self-Construal, and Social Capital in Gaming Context. Int. J. Psychol. Behav. Sci. 2015, 9, 2306–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wann, D.L.; Carlson, J.D.; Holland, L.C.; Jacob, B.E.; Owens, D.A.; Wells, D.D. Beliefs in symbolic catharsis: The importance of involvement with aggressive sports. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 1999, 27, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, G.W. Violent sports entertainment and the promise of catharsis. Z. Medienpsychol. 1993, 5, 101–105. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, G.W. Catharsis Through Sports: Fact or Fiction? Soc. Psychol. Sport 1993, 211–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchrowicz-Mośko, E.; Wieliński, D.; Adamczewska, K. Perceived Benefits for Mental and Physical Health and Barriers to Horseback Riding Participation. The Analysis among Professional and Amateur Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, K.D. The Value of Youth Education in Taekwondo Training: Scientific Evidence for the Benefits of Training Children. Taekwondo J. Kukkiwon 2013, 4, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Gender | Age | Demonstration Team Career | Taekwondo Grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant 1 | M | 23 | 5 years | 4th Dan |

| Participant 2 | F | 22 | 5 years | 4th Dan |

| Participant 3 | M | 21 | 6 years | 3rd Dan |

| Participant 4 | M | 22 | 3 years | 4th Dan |

| Participant 5 | F | 23 | 4 years | 4th Dan |

| Participant 6 | M | 21 | 4 years | 4th Dan |

| Participant 7 | M | 24 | 6 years | 5th Dan |

| Participant 8 | M | 24 | 5 years | 5th Dan |

| Participant 9 | F | 20 | 1 year | 4th Dan |

| Participant 10 | F | 21 | 4 years | 4th Dan |

| Participant 11 | M | 24 | 5 years | 5th Dan |

| Participant 12 | M | 25 | 5 years | 5th Dan |

| Interview Question |

|---|

| Could you tell me about your Taekwondo demonstration team activities? When was the happiest moment during Taekwondo demonstration team activities? Have you ever experienced any stress relief or catharsis during Taekwondo training or demonstration performance? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bing, W.-C.; Kim, S.-J. A Phenomenological Study of Mental Health Enhancement in Taekwondo Training: Application of Catharsis Theory. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084082

Bing W-C, Kim S-J. A Phenomenological Study of Mental Health Enhancement in Taekwondo Training: Application of Catharsis Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(8):4082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084082

Chicago/Turabian StyleBing, Won-Chul, and Soo-Jung Kim. 2021. "A Phenomenological Study of Mental Health Enhancement in Taekwondo Training: Application of Catharsis Theory" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 8: 4082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084082

APA StyleBing, W.-C., & Kim, S.-J. (2021). A Phenomenological Study of Mental Health Enhancement in Taekwondo Training: Application of Catharsis Theory. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4082. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18084082